Abstract

Conscious awareness of hill slant is overestimated, but visually guided actions directed at hills are relatively accurate. Also, steep hills are consciously estimated to be steeper from the top as opposed to the bottom, possibly because they are dangerous to walk down. In the present study, participants stood at the top of a hill on either a skateboard or a wooden box of the same height. They gave three estimates of the slant of the hill: a verbal report, a visually matched estimate, and a visually guided action. Fear of descending the hill was also assessed. Those participants that were scared (by standing on the skateboard) consciously judged the hill to be steeper relative to participants who were unafraid. However, the visually guided action measure was accurate across conditions. These results suggest that our explicit awareness of slant is influenced by the fear associated with a potentially dangerous action.

“[The phobic] reported that as he drove towards bridges, they appeared to be sloping at a dangerous angle.” (Rachman and Cuk 1992 p. 583).

Does fear really make us see a hill differently? Previous research has shown that steep hills are consciously estimated to be steeper from the top as opposed to the bottom, possibly because these hills were too steep to walk down and were viewed as dangerous (Proffitt et al 1995). Typically in these studies, the conscious awareness of the slant of a hill was overestimated, but visually guided actions directed at the hill were relatively accurate (Bhalla and Proffitt 1999; Proffitt et al 1995; Proffitt et al 1999; Witt and Proffitt 2007). Furthermore, when an observer’s physiological potential was manipulated by having him go on a long run or wear a heavy backpack, hills appeared even steeper with the conscious measures of slant, but the visually guided action remained unaffected (Bhalla and Proffitt 1999). In the present studies, we extend this research to show that viewing the hill in a fearful way also increases conscious estimates of slant, but not visually guided actions. The results suggest that anecdotal reports of perceptual distortions from highly fearful individuals may be accurate.

The experimenter stood at the top of the 7° paved hill with a sign advertising the experiment and participants stopped if they were interested. Participants stood at the top of the hill either on a skateboard (that was secured in place with wooden blocks) or on a wooden box of the same height. The box served as a control for the skateboard because it equated eye-height without being dangerous. All participants were then asked to imagine themselves going down the hill. Then, they gave three estimates of the slant of the hill (in randomized order): verbal report of the angle of the hill in degrees, a visually matched estimate of the slant using a visual disk to match the angle of the hill with a representation of the cross-section of the hill, and a visually guided action using a haptic palmboard (for further description of methodologies, see Proffitt et al 1995). After participants gave the slant estimates, their fear of descending the hill was assessed on a continuous rating scale by one question embedded in a larger questionnaire. Experience on skateboards was also assessed, but no participant had substantial experience with skateboarding.

On average, participants verbally estimated the hill to be 24.7°, visually matched the angle of the hill to be 19.8°, and adjusted the palmboard to be 13.2°. These estimates were in the expected range, given the normative slant estimates collected by Proffitt et al (1995). Across conditions, participants’ self-reported ratings of fear were significantly correlated with their visual matched angle of the hill, r = .53, p < .0001. Additionally, those participants who stood on the skateboard verbally judged the hill to be steeper, F(1,63) = 4.7, p = .03, than those who stood on the box. A similar difference was not significant for the visual matching measure. However, subsequent analyses which included only participants for whom the fear manipulation was clearly successful suggest that fear increased slant perception operated on the visual matching measure, as well as on the verbal measure. Specifically, we eliminated from the analysis the 10 individuals in the skateboard condition and 10 in the control condition whose fear scores fell on the wrong side of the median for their condition; see Storbeck and Clore 2005 for a similar procedure). The resulting groups (n = 20 for each group) showed significant differences in their fear ratings (skateboard M = 5.9, control M = 2.4), t(38) = 14.02, p < .0001.

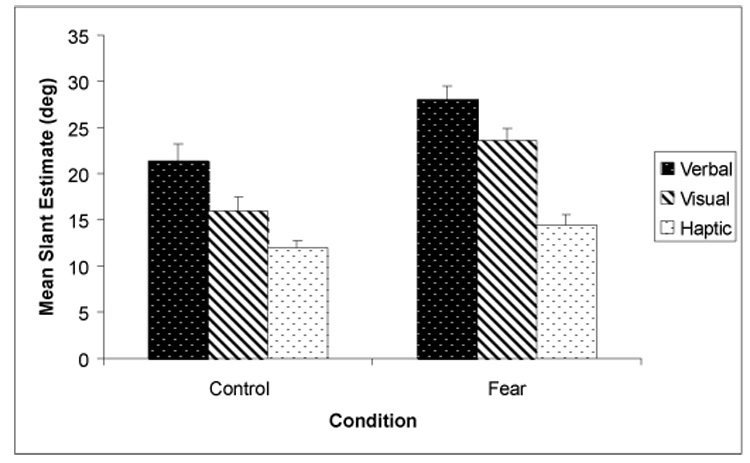

Those participants that stood on the skateboard and reported fear verbally judged the hill to be steeper, F(1,38) = 8.3, p = .007, and exhibited a greater overestimation with the visual matching measure, F(1,38) = 15.0, p < .0001, relative to those participants who stood on the box and were unafraid. However, the visually guided action measure was unaffected by the fear-induction manipulation, p = .10 (see Figure 1). These results suggest that our explicit awareness of slant is influenced by the fear associated with a potentially dangerous action. As found previously, the visually guided action was unaffected.

Figure 1.

Fear group differences for the three estimates of geographical slant.

It is a widely observed clinical phenomenon that people with extreme fears experience perceptual distortions (e.g., Rachman and Cuk 1992). This study provides preliminary evidence that manipulating observers’ emotional state can alter their perception of geographical slant. Fearful individuals see a hill as steeper than those who are unafraid.

The question remains as to the mechanisms through which fear influences slant perception. Did fear alter the physiology of the observer, which in turn influenced his perception of the hill? The fear response has multiple components: physiological, cognitive, and behavioral (Lang 1979). One, two, or all of these components could influence perception. Alternatively, perceptual distortions could produce elevated fear responses or the relationship could be reciprocal, with fear and perception influencing each other.

Another possibility is that this effect is due to an influence of fear on post-perceptual reports rather than perception, itself. Observers may have intuited the hypothesis and biased their judgments accordingly. However, the results of this experiment suggest that the effect is due to a change in perception rather than to a response bias. Participants estimated slant with three converging measures, visual matching, verbal reports, and adjustments of the haptic palmboard. That the palmboard adjustments were unaffected by the experimental manipulation provides evidence that the effect of fear was not due to a response bias. If participants had intuited the intent of the experimental manipulation, and thereby, acquired a response bias, then this bias should have been observed on all of the measures. It was not.

Other research also suggests that the effect observed in this experiment was perceptual. Teachman et al (2007) recently found that people who are especially fearful of height overestimate heights more than do less fearful individuals. In addition, Phelps et al (2006) showed that fear can influence even low-level visual processes, like contrast sensitivity.

Fear influences behaviors and beliefs related to the environment, as evidenced by the anecdotal reports from clinical psychologists studying extreme fears. Our study suggests that these anecdotal reports are perceptual realities.

References

- Bhalla M, Proffitt DR. Visual-Motor Recalibration in Geographical Slant Perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1999;25:1–21. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.25.4.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ. A bio-informational theory of emotional imagery. Psychophysiology. 1979;16:495–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1979.tb01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA, Ling S, Carrasco M. Emotion facilitates perception and potentiates the perceptual benefits of attention. Psychological Science. 2006;17:292–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt DR, Bhalla M, Gossweiler R, Midgett J. Perceiving geographical slant. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1995;2:409–428. doi: 10.3758/BF03210980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt DR, Creem SH, Zosh W. Seeing mountains in mole hills: Geographical slant perception. Psychological Science. 2001;12:418–423. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachman S, Cuk M. Fearful distortions. Behavioral Research Therapy. 1992;30:583–589. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(92)90003-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storbeck J, Clore GL. With sadness comes accuracy, with happiness, false memory: Mood and the false memory effect. Psychological Science. 2005;16:785–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman BT, Stefanucci JK, Clerkin EM, Cody MW, Proffitt DR. New modes of fear expression: Perceptual and implicit association biases in height fear. 2007 doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.2.296. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt JK, Proffitt DR. Perceived slant: A dissociation between perception and action. Perception. 2007;36:249–257. doi: 10.1068/p5449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]