Abstract

The prototypic hypovirus CHV1-EP713 attenuates virulence (hypovirulence) and alters several physiological processes of the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica. The papain-like protease, p29, and the highly basic protein, p40, derived, respectively, from the N-terminal and C-terminal portions of the CHV1-EP713-encoded open reading frame (ORF) A polyprotein, p69, both contribute to reduced pigmentation and sporulation. The p29 coding region was shown to suppress pigmentation and asexual sporulation in the absence of virus infection in transformed C. parasitica, whereas transformants containing the p40-coding domain exhibited a wild-type, untransformed phenotype. Deletion of either p29 or p40 from the viral genome also results in reduced accumulation of viral RNA. We now show that p29, but not p40, functions in trans to enhance genomic RNA accumulation and vertical transmission of p29 deletion mutant viruses. The frequency of virus transmission through conidia was found to decrease with reduced accumulation of viral genomic double-stranded RNA (dsRNA): from almost 100% for wild-type virus to ∼50% for Δp29, and 10 to 20% for Δp69. When expressed from a chromosomally integrated cDNA copy, p29 elevated viral dsRNA accumulation and transmission for Δp29 mutant virus to the level shown by wild-type virus. Increased viral RNA accumulation levels were also observed for a Δp69 mutant lacking almost the entire ORF A sequence. Such enhancements were not detected in transgenic fungal colonies expressing p40. Mutation of p29 residues Cys70 or Cys72, strictly conserved in hypovirus p29 and potyvirus HC-Pro, resulted in the loss of both p29-mediated suppressive activity in virus-free transgenic C. parasitica and in trans enhancement of RNA accumulation and transmission, suggesting a linkage between these functional activities. These results suggest that p29 is an enhancer of viral dsRNA accumulation and vertical virus transmission through asexual spores.

Members of the virus family Hypoviridae (22) persistently attenuate virulence (hypovirulence) and stably alter complex biological processes upon infection of their fungal host, the chestnut blight fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica. Infection-related phenotypic changes can include suppressed pigment production and asexual sporulation, altered colony morphology, loss of female fertility and modified expression of specific host genes (1, 18, 28, 31). Infectious hypovirus cDNA clones (8, 10) and a robust transformation protocol for C. parasitica (15) provide a versatile system for identifying virus-encoded symptom determinants and modulators of hypovirus replication.

Choi and Nuss (13) showed that transformation of virus-free C. parasitica with the 5′-proximal coding domain, open reading frame (ORF) A, resulted in suppressed conidiation and pigmentation but no change in fungal virulence. ORF A encodes a papain-like protease, p29, and a highly basic protein, p40, derived, respectively, from the N terminus and C terminus of polyprotein, p69, by a p29-mediated autocatalytic cleavage event (11, 12). Craven et al. (16) subsequently used a similar transformation approach to map the suppressive activity to p29. This finding was confirmed by the same authors by using transfection analysis in which deletion of 88% of the p29 coding domain, excluding the first 24 codons, in the context of the CHV1-EP713 infectious cDNA clone (mutant virus Δp29) resulted in a viable mutant that caused milder symptoms (less suppressed pigmentation and conidiation) but still conferred hypovirulence (16).

Suzuki et al. (42) subsequently mapped the p29 symptom determinant domain to a region extending from Phe25 to Gln73 by a gain-of-function analysis involving progressive repair of the Δp29 mutant virus. This region, which shows a moderate level of amino acid sequence similarity to the multifunctional HC-Pro papain-like protease (7) encoded by plant-infecting potyviruses, includes four strictly conserved cysteine residues: Cys38, Cys48, Cys70, and Cys72. Mutations in this region of potiviral HC-Pro affect aphid transmissibility, symptom development, and virus accumulation (5, 6, 17, 29, 45). Mutations of the CHV1-EP713 infectious cDNA involving cysteine-to-glycine substitutions identified conserved p29 Cys70 and Cys72 as having crucial roles in p29-mediated phenotypic modulations. Given the proposed evolutionary relationship between hypoviruses and potyviruses (27), these results raise the possibility that p29 and HC-Pro modulate cellular regulatory pathways through similar mechanisms in the respective fungal and plant hosts.

Deletion of the C-terminal portion of ORF A, which encodes the highly basic protein, p40, resulted in a replication-competent mutant virus (Δp40) that was, however, significantly reduced in RNA accumulation. While the Δp40 mutant retained the ability to confer hypovirulence, Δp40-infected fungal strains produced more asexual spores than strains infected with either wild-type CHV1-EP713 or a Δp29 mutant virus. As observed for Δp29-infected colonies, pigment production was significantly increased in Δp40-infected fungal strains relative to CHV1-EP713-infected strains (44). The activity domain of p40 responsible for efficient viral replication was mapped to the N-terminal domain Thr40-Arg64 by a gain-of-function analysis with p40 deletion mutant viruses. Moreover, restoration of symptoms directly correlated with increased accumulation of viral RNA.

It was observed, while characterizing the Δp40 mutants of CHV1-EP713, that deletion of p29 also resulted in some reduction in viral RNA but to a lesser extent than that resulting from deletion of p40 (44). Thus, some of the reduced suppression of pigmentation and sporulation exhibited by the Δp29 mutants is likely due to reduced viral RNA accumulation. However, since p29-mediated suppressive activity occurs in transformed strains expressing p29 in the absence of virus infection, it appears that p29 alters host phenotype both directly through action of the protein on host factors and indirectly by contributing to viral RNA accumulation. In contrast, no phenotypic changes are observed in virus-free C. parasitica transformants expressing p40. Thus, p40 appears to alter host phenotype only indirectly through its accessory role in amplifying viral RNA accumulation.

We now report evidence that p29 functions in cis and in trans to enhance genomic RNA accumulation and vertical transmission of p29 deletion mutant viruses, but that p40, expressed from a chromosomally integrated cDNA copy, appears to have no effects on double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) accumulation, viral transmission, or virus-mediated phenotypic alterations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of mutant virus cDNAs and transforming DNA.

The plasmid DNA clones used for transfection and transformation are summarized in Table 1. All transfecting plasmids and some of transforming plasmids were prepared previously as indicated in the table. Transformation plasmids pCPwtp29, pCPCys70p29, and pCPCys72p29 were constructed on the foundation vector, pCPXHY1 (16). The p29 coding domain was amplified from cDNA of full-length wild-type virus (in plasmid pLDST) (14) and from cDNAs of mutant viruses [Cys(70) and Cys(72) (42) by using Pfu DNA polymerase (38) with a primer set consisting of NS26 (CACGAGCTCGACCCCGAACGAGGTCCGAACATAATGG; the boldface sequence is a SacI recognition site) and NS27 (CACGCATGCTTAGCCAATCCGGGCAAGGGGATCCTTCTCGG; the sequence in boldface is an SphI recognition site, followed by a termination codon shown in italics). The resulting fragments were inserted into the SacI-SphI site of pCPXHY1 to obtain pCPwtp29, pCPCys70p29, and pCPCys72p29. An artificial translation termination codon, UAA, was added to the 3′ end of p29 coding domain of each of these plasmids.

TABLE 1.

Transfecting and transforming DNA clones

| Plasmid | Expt | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| pLDST | Transfection | Wild-type CHV1-EP713 cDNA | 14 |

| Cys70 | Transfection | Full-length virus cDNA with a Cys-Gly substitution at p29 residue 70 | 42 |

| Cys72 | Transfection | Full-length virus cDNA with a Cys-Gly substitution at p29 residue 72 | 42 |

| Δp29 | Transfection | Mutant virus cDNA lacking 87.5% of the p29 coding domain | 16 |

| Δp40a | Transfection | Mutant virus cDNA lacking 96.5% of the p40 coding domain | 44 |

| Δp40b | Transfection | Mutant virus cDNA lacking 99.5% of the p40 coding domain | 44 |

| Δp69a | Transfection | Mutant virus cDNA lacking 94.4% of the p69 coding domain | 44 |

| Δp69b | Transfection | Mutant virus cDNA lacking 96.1% of the p69 coding domain | 44 |

| pCPwtp29 | Transformation | Wild-type p29 coding sequence | This study |

| pCPCys70p29 | Transformation | p29 coding domain with a Cys-Gly substitution at residue 70 | This study |

| pCPCys72p29 | Transformation | p29 coding domain with a Cys-Gly substitution at residue 72 | This study |

| pXH3 | Transformation | Wild-type p40 coding domain | 16 |

| pCPEGFP | Transformation | EGFP gene | 43 |

Transfection and transformation of C. parasitica spheroplasts.

Tranforming DNA plasmids listed in Table 1 were introduced with the polyethylene glycol-mediated technique under the conditions described by Choi and Nuss (14) into spheroplasts prepared from C. parasitica strain EP155 (ATCC 38755) according to the method of Churchill et al. (15). Homokaryons of hygromycin-resistant transformants were obtained through single conidium-germinate selection.

Mutant virus cDNA transfecting plasmids, all of which have the T7 RNA polymerase promoter upstream of the CHV1-EP713 5′-noncoding sequence, were utilized as a template for in vitro RNA synthesis with the T7 RNA polymerase after linearization with restriction enzyme SpeI. Reaction conditions followed manufacturer's recommendations (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). The synthetic plus-sense transcripts were transfected by electroporation (8) into C. parasitica spheroplasts. Surviving spheroplasts were cultured on high osmotic solid regeneration media for 7 to 9 days to allow cell wall formation and movement of replicating viral RNA through the regenerated mycelia and then transferred to potato dextrose agar (PDA; Difco, Detroit, Mich.) plates for phenotypic measurements and to potato dextrose broth (PDB; Difco) for nucleic acid isolation.

RNA preparation.

Total RNA was prepared from C. parasitica mycelia cultured in 20 ml of PDB as described by Suzuki and Nuss (44). Harvested mycelia were homogenized with a mortar and pestle in the presence of liquid nitrogen. Nucleic acids were isolated by two rounds of phenol-chloroform extraction in 4 ml of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, 4 mM EDTA, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate and then precipitated by the addition of 2 volumes of ethanol. To eliminate fungal chromosomal DNA, extracted nucleic acids were treated twice with RQ1 DNase I (Promega, Madison, Wis.), followed by phenol, phenol-chloroform, and chloroform extractions and ethanol precipitation. The final RNA concentration was adjusted to an optical density at 260 nm (OD260) of 25 and used for agarose gel electrophoresis and real-time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analyses. In preparation for Northern analysis, total RNA fractions were enriched for single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) by the addition of LiCl to a final concentration of 2 M and incubation for 1 h at 4°C. Single stranded RNA was collected by centrifugation, taken through one round of ethanol precipitation and used for Northern analysis.

Total RNA was also purified from asexual spores. Conidia were liberated from fungal colonies grown on PDA with 0.15% Tween 80 as described by Hillman et al. (23) and purified by differential centrifugation and sucrose gradient centrifugation. Following filtering through two layers of Miracloth (Calbiochem, San Diego, Calif.) to remove hyphal fragments, conidia were collected by low-speed (3,000 rpm, 5 min) centrifugation, suspended in distilled water, layered onto a 10 to 40% sucrose stepwise gradient and centrifuged for 4 min at 3, 000 rpm. Spores at the middle portion of the gradient were recovered and concentrated by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 5 min. Spores in the pellet were suspended in 0.5 ml of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 200 mM NaCl, 4 mM EDTA and 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate and transferred to a 1.5-ml microtube. Nucleic acids were extracted from the purified conidia by homogenization along with abrasive quartz sand with the aid of a microtube-fitting pestle, and treated with phenol and phenol-chloroform. Total RNA was prepared as described above, including digestion of DNA with RQ1 DNase I, and then subjected to viral RNA quantitative analysis.

Viral dsRNA quantification.

The relative levels of viral genomic dsRNA accumulation in fungal colonies infected with wild-type and mutant viruses was examined by semiquantitative real-time RT-PCR as described by Suzuki and Nuss (44). cDNA synthesis was primed on two different denatured RNA molecules, the viral negative-stranded RNA and C. parasitica 18S rRNA, in a single tube with oligonucleotide primers NS52PE and PDF1439R (see reference 44 for the primer sequences), respectively. The relative amounts of viral RNA were quantified by amplifying the viral cDNA products with ExTaq polymerase in the ExTaq RT-PCR master mix (Takara Bio, Inc., Outsu, Japan), exploiting the 5′ nuclease assay in a SmartCycler system (Takara Bio). Viral RNA values were normalized against 18S rRNA cDNA. The primer sets used in the PCR were PDF1373F and PDF1439R for 18S rRNA and NS52PE and NS53PE for viral RNA. PDF1373F was designed to span the insertion site of a 547-bp intron found in the C. parasitica 18S rRNA gene so that only rRNA cDNA is amplified (32). The terminal portion of the CHV1-EP713 genome (map positions 12,341 to 12,488) was chosen for amplification because this region is conserved in internally deleted RNA species that are frequently generated in hypovirus infected fungal isolates (40).

Alternatively, viral genomic dsRNA was quantified by densitometry. Total RNA from each transfectant was electrophoresed in a 0.7% agarose gel in the TAE (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.8]) buffer system and stained with ethidium bromide. The resulting gel image was incorporated into and analyzed with an Atto (Tokyo, Japan) densitometer. Relative amounts of viral dsRNA were determined by measuring the area of viral bands and normalizing it against that of 18S rRNA.

Northern blot analysis.

Total ssRNA (0.2, 0.4, or 20 μg) was denatured in 1× MOPS buffer (20 mM 3-[N-morpholino]propanesulfonic acid [pH 7.0], 2 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA) containing 3.7% formaldehyde and 42.5% formamide at 65°C for 15 min, followed by electrophoresis through a 1.4% agarose gel containing 2% formaldehyde as described by Sambrook et al. (39). Fractionated RNA was capillary transferred onto Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Buckingham, England) and probed by dioxigenin (DIG)-11-dUTP-labeled DNA fragments amplified by PCR according to the method recommended by the manufacturer (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Prehybridizations and hybridizations were carried out with the DIG Easy-Hyb granules kit according to the instructions provided by the supplier (Roche). Probe-RNA hybrids were treated with anti-DIG antibodies conjugated with alkaline phosphatase and subjected to chemiluminescent analysis by using a DIG detection kit and a CDP Star kit (Roche). Chemiluminescent signals were visualized in a Hamamatsu Photonics real-time image-processor model Argus-50 (Hamamatsu Photonics KK, Hamamatsu, Japan).

Virus transmission assay.

Fungal colonies were cultured on PDA for 2 weeks in an environmentally controlled chamber at 25°C with a 12-h photoperiod. Conidia were harvested in 0.15% Tween 80 as described above. After they were counted with the aid of a hemacytometer, the spores were spread onto 10-cm PDA plates at appropriate dilutions. The plates were cultured at bench top for 2 to 3 days to allow spore germination. Single-spore germinates were transferred to new PDA plates, each containing 10 independent germinates. These were cultured at bench top for an additional 2 to 4 weeks in order to score infected germinates. Diagnosis was performed by careful visual examination of phenotypic markers, including pigmentation, sporulation, and colony morphology.

RESULTS

CHV1-EP713 protein p29 acts in trans to enhance levels of virus genomic RNA and virus transmission. Suzuki and Nuss (44) recently reported that p29 mutant viruses lacking 88% of the p29 coding domain, either in the context of wild-type virus (mutant virus Δp29) or in the absence of the p40 coding domain (mutant virus Δp69), retained the ability to replicate but were reduced in the levels of viral RNA accumulation, e.g., ca. 60% reduction for Δp29 and 80 to 90% reduction for Δp69 relative to wild-type CHV1-EP713. Since p29 causes phenotypic changes when expressed in transformed C. parasitica in the absence of virus infection, it was of interest to determine whether p29 would also function in trans to enhance p29 mutant viral RNA accumulation.

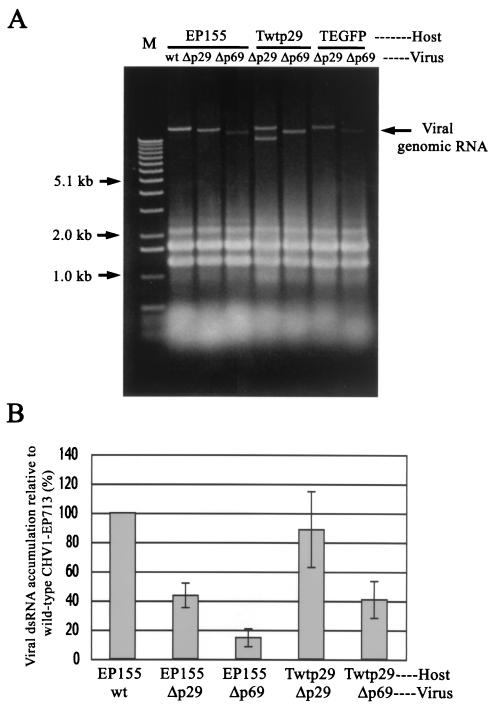

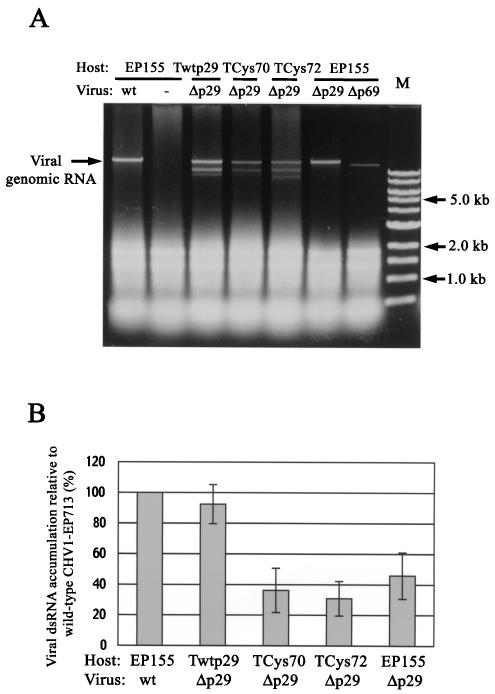

As described earlier (44) and as shown in Fig. 1, the accumulation of genomic dsRNA for mutant viruses Δp29 and Δp69 was significantly decreased, relative to that for full-length CHV1-EP713, in untransformed C. parasitica strain EP155 (lanes 2 and 3). Interestingly, the level of Δp29 RNA accumulation was restored to near wild-type levels in fungal host lines transformed with the p29 coding domain (Twtp29) (Fig. 1A, lanes Δp29/Twtp29 versus Δp29/EP155; Fig. 1B). The in trans augmentation by transgenic expression of p29 was approximately threefold (from <10% to >40% of the wild-type virus accumulation) for the Δp69 mutant virus (Fig. 1A, lanes Δp69/Twtp29 versus Δp69/EP155; Fig. 1B). In contrast, no significant increase in mutant viral dsRNA accumulation was detected in control lines transformed with the Aequorea victoria enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) gene (37) (Fig. 1A, Δp29/and Δp69/TEGFP).

FIG. 1.

Elevation of viral genomic dsRNA accumulation levels by chromosomally expressed CHV1-EP713-encoded protein p29. (A) Agarose gel electrophoretic analysis of total RNA from mycelia of p29 transformants infected with p29 mutant viruses Δp29 and Δp69. As described in Materials and Methods, equal amounts (0.25 OD) of total RNA isolated from the mycelia of nontransformant (EP155), p29 transformant (Twtp29), or EGFP transformant (TEGFP) (43) that were infected with wild-type (wt), Δp29, or Δp69b (Δp69) mutant CHV1-EP713 were applied to each well of a 0.7% agarose gel and electrophoresed in a 1× TAE buffer system. M, 1-kb DNA ladder standards (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, Md). (B) Relative accumulation of viral minus strand-RNA in wild-type CHV1-EP713- and mutant virus-infected fungal colonies. Total RNA (shown in panel A) was isolated from untransformed (EP155) or p29-transformed (Twtp29) mycelia infected with wild-type CHV1-EP713 (wt) and mutant viruses Δp29 and Δp69b (Δp69) and used for strand-specific cDNA synthesis after denaturation in 90% dimethyl sulfoxide at 65°C (4). The resulting cDNA was subject to semiquantitative PCR analysis in a SmartCycler system (Takara) with cDNA of 18S rRNA generated in the same reverse transcriptase reaction for normalization. The sequences of primers and TaqMan probes used in the quantification were as described previously (44). Viral negative-strand RNA accumulation levels are reported as a percentage of the value measured for CHV1-EP713-infected colonies, with standard deviations indicated by the error bars based on three independent measurements.

In addition to genomic dsRNA, faster-migrating dsRNA bands were observed in some RNA preparations (e.g., Δp29/Twtp29). These previously described 8- to 10-kbp defective RNAs (40) contain deletions confined to the middle portion of ORF B residing at least 3.5 kb from each terminus and have never been found to be associated with any modulation of hypovirus-mediated symptoms. Consequently, when present, these internally deleted RNAs were quantified as genomic dsRNAs (see Methods and Materials).

Virus transmission efficiency is considerably different among wild-type and mutant viruses and is increased by p29 transgenic expression.

The observation by Chen et al. (9) that Δp29 is reduced, relative to wild-type hypovirus, in vertical transmission in several host fungi, including C. parasitica and C. havanensis, suggested potential roles for hypovirus-encoded proteins in virus transmission through conidia. To further investigate the involvement of hypoviral proteins in vertical transmission, the transmission rates for a number of previously described deletion mutant viruses (Δp29, Δp40a, Δp40b, Δp69a, and Δp69b) were investigated. The mean frequency values for virus transmission through conidia are shown in Table 2. The p29 deletion mutant virus, Δp29 was transmitted at an efficiency of 48.5% compared to the value exhibited by wild-type virus CHV1-EP713, confirming the previously reported results by Chen et al. (9). Further reduction in virus transmission was observed for Δp40a, Δp40b, Δp69a and Δp69b, each of which showed similar transmission rates ranging from 10.7% (for Δp69b) to 21.3% (for Δp40a). These results suggested that not only p29, but also p40, are involved in the modulation of hypoviral vertical transmission frequency.

TABLE 2.

Efficiency of hypovirus transmission through conidia

| Host straina | virus strain | No. of infected spore germinates/No. of tested spore germinates

|

Totalsb | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expt 1 | Expt 2 | Expt 3 | Expt 4 | ||||

| EP155 | Wild-type | 65/65 | 70/70 | 65/65 | 52/52 | 249/249 | 100 |

| EP155 | Δp29 | 27/54 | 54/111 | 69/107 | 34/107 | 184/379 | 48.5 |

| EP155 | Δp40a | 7/63 | 22/100 | 25/108 | 24/96 | 78/367 | 21.3 |

| EP155 | Δp40b | 3/21 | 10/104 | 8/53 | 25/115 | 46/293 | 15.7 |

| EP155 | Δp69a | 3/24 | 17/101 | 9/28 | 13/101 | 42/254 | 16.5 |

| EP155 | Δp69b | 2/28 | 10/104 | 2/19 | 13/101 | 27/252 | 10.7 |

| Twtp29 | Δp29 | 94/107 | 87/97 | 89/90 | 270/294 | 91.8 | |

| TCys70p29 | Δp29 | 31/91 | 24/85 | 18/80 | 73/256 | 28.5 | |

| TCys72p29 | Δp29 | 41/120 | 17/73 | 19/101 | 77/294 | 26.2 | |

| Tp40 | Δp40b | 19/104 | 13/104 | 9/90 | 41/298 | 13.8 | |

Host strains Twtp29, TCys70p29, TCys72p29, and Tp40 are transformants with the coding sequences for wild-type p29, p29Cys70-Gly, p29Cys72-Gly, and wild-type p40, respectively.

Total number of infected spore germinates/the total number of tested spore germinates.

Since p29 is able to reduce pigmentation and sporulation in C. parasitica transformants in the absence of virus infection and functions in trans to elevate mutant viral genomic RNA, it was of interest to investigate whether p29 acted in trans to enhance virus transmission. As shown in Table 2, p29 expressed from fungal chromosomes (Twtp29) raised the virus transmission rate of Δp29 from 48.5% to 91.8%, a frequency similar to that exhibited by wild-type virus.

Virus transmission frequencies correlate with virus accumulation levels in conidia.

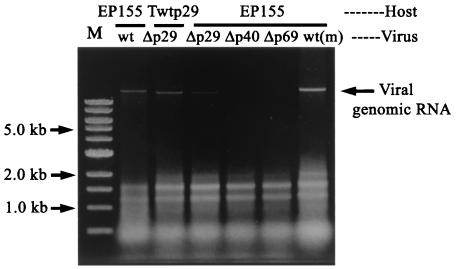

As shown above, hypovirus vertical transmission frequencies varied among wild-type and mutant viruses and were elevated by expression of p29 regardless of whether provided in trans or in cis. To gain further insights into the mechanism underlying the differing efficiencies of virus transmission, virus genomic dsRNA concentrations were quantified in asexual spores. Total RNA was isolated from purified asexual spores recovered from colonies infected with different virus strains and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis. As shown in Fig. 2, the relative accumulation patterns for wild-type and mutant viral genomic RNAs in conidia is similar to that observed in mycelia (Fig. 1). Moreover, there is a good correlation between the relative levels of wild-type and mutant virus RNA accumulation in conidia and transmission frequencies (Table 2). Wild-type virus, with a 100% transmission rate, also showed the highest level of dsRNA accumulation in conidia (Fig. 2, lane wt), followed by the mutant viruses Δp29 (48.5% transmission), Δp40 (15 to 21% transmission), and Δp69 (10 to 16% transmission). It should be noted that the ssRNA in total RNA preparations isolated from spores infected with wild-type CHV1-EP713 reproducibly (16 of 19 preparations) showed signs of some degradation relative to the ssRNAs in all other RNA preparations isolated from spores infected with mutant viruses (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Although this slightly complicated the quantitative comparisons of viral dsRNA, it is clear from inspection of Fig. 2 that p29, when furnished in trans, causes an enhanced accumulation of Δp29 mutant viral genomic dsRNA in conidia (Fig. 2, lane Δp29/Twtp29 versus lane Δp29/EP155) as was observed in mycelia (Fig. 1).

FIG. 2.

Virus dsRNA accumulation in asexual spores produced on C. parasitica colonies infected with different virus strains. Untransformed fungal colonies infected with wild-type CHV1-EP713 (wt), with Δp29, or with Δp69b (Δp69), and p29 transformants (Twtp29) infected with Δp29 were cultured in moderate light conditions for 2 weeks. Spores formed on these colonies were purified by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. Total RNA in purified spores were extracted as described in Materials and Methods, and equal quantities (0.2 OD units) were applied to each lane of a 0.7% agarose gel in 1× TAE. Lane wt(m) contained total RNA from mycelia of EP155 infected with CHV1-EP713. RNA was extracted at least four times for each strain, and representative agarose gel electrophoresis patterns are shown.

Mutations at Cys70 and Cys72 abolish the ability of p29 to alter fungal phenotype and enhance viral RNA replication and virus transmission.

Site-directed mutational analyses within the p29 symptom determinant domain (codons 25 to 73) of the CHV1-EP713 infectious cDNA clone identified Cys70 and Cys72 as having crucial roles in phenotypic alterations (42). That is, Cys-Gly substitutions at p29 residue 70 or 72 within the context of the infectious cDNA clone resulted in replication-competent virus mutants [Cys(70) and Cys(72)] that caused different symptoms than that exhibited by wild-type virus. Cys(70)-infected colonies manifested a profoundly modified phenotype that included extremely reduced and distorted growth, whereas Cys(72) caused symptoms similar to the p29 deletion mutant, Δp29. It was, therefore, of interest to determine whether these cysteine residues were also important for viral RNA accumulation.

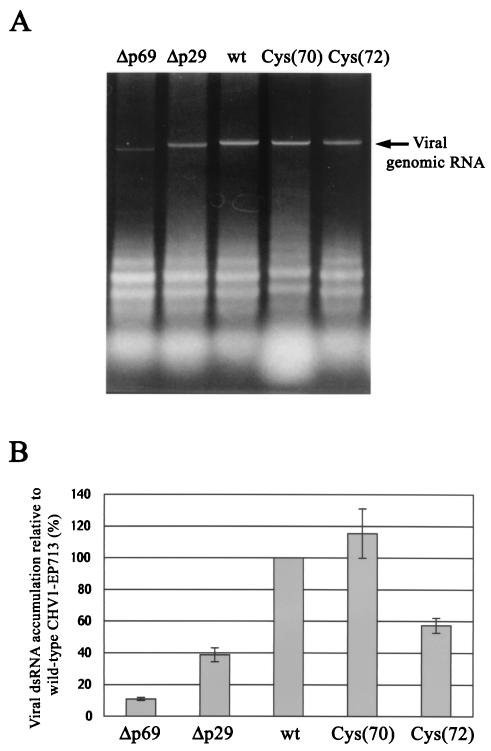

When normalized against rRNA, Cys(70) dsRNA accumulated to a level slightly greater than that of wild-type virus, while accumulation of Cys(72) dsRNA was found to be less than wild-type but greater than that of Δp29 (Fig. 3). It is noteworthy that when normalized against total RNA, Cys(70) dsRNA levels were determined to be lower than that of wild-type virus. This is because, relative to preparations of other virus strains, the Cys(70) RNA preparation contained greater amounts of low-molecular-weight RNA that migrated faster than tRNA [Fig. 3, lane Cys(70)]. The significance and properties of this low-molecular-weight RNA remain to be determined.

FIG. 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis profile and semiquantification of viral dsRNA in transfectants infected with p29 cysteine mutant viruses. (A) Total RNA fractions were isolated from C. parasitica strain EP155 infected with wild-type hypovirus CHV1-EP713 (wt), Δp29, Cys(70), or Cys(72). Cys(70) and Cys(72) are mutant viruses that have a cysteine-to-glycine mutation at p29 residues 70 and 72, respectively (42). Due to the poor growth characteristics of Cys(70)-infected mycelia, three 20-ml PDB cultures were harvested for RNA preparations, whereas a single 20-ml PDB culture was used for the other infected fungal strains. Electrophoresis was carried out in 1× TAE (40 mM Tris-acetate and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.8]). All gel wells were loaded with 0.2 OD units of total RNA, except for the well-labeled Cys(70), which received 0.4 OD units of total RNA due to the presence of a greater abundance of small RNA that migrated faster than tRNA. (B) Quantitative comparison of virus dsRNA in mycelia infected with p29 cysteine mutant viruses. The image of ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels shown in panel A was processed in an ATTO densitograph to semiquantify viral genomic dsRNA from mycelia infected with Δp69b (Δp69b), Δp29, and Cys(70) and Cys(72). For each strain the average and standard deviation of four independent preparations were obtained.

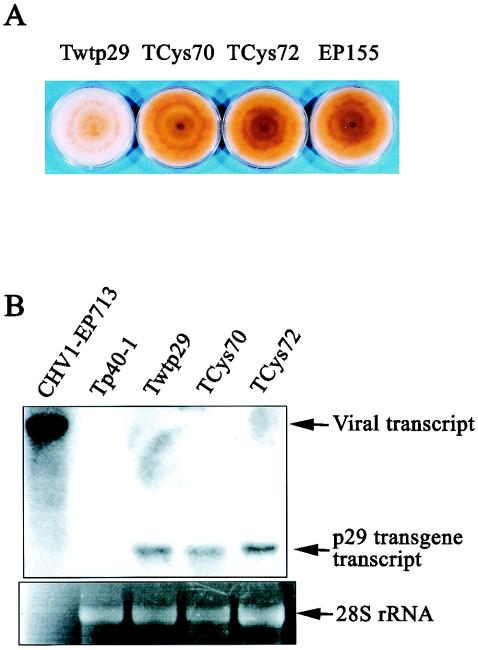

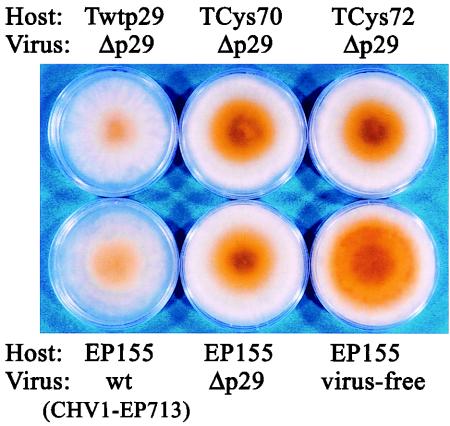

It was also of interest to know whether the p29 protein containing the glycine substitutions at Cys70 (p29Cys70-Gly) and Cys72 (p29Cys72-Gly) were still able to alter the pigmentation and spore formation when expressed from fungal chromosomes independently of virus infection. Colonies transformed with the p29Cys70-Gly and p29Cys72-Gly mutant coding sequences (TCys70 and TCys72) were prepared and examined for their suppressive activity. At least 10 independent transformant colonies were examined for each of the p29 variants and for control transformants containing the wild-type p29 coding domain. None of the p29 variant transformants were judged to be phenotypically different from the untransformed control strain EP155, whereas all of the wild-type p29 transformants exhibited the expected white suppressive phenotype. Representative colonies are shown in Fig. 4A. Northern analysis confirmed that introduced p29 coding domains were being expressed at similar levels for the wild-type and variant sequences (Fig. 4B). It was therefore concluded that Cys70 and Cys72 are required for p29-mediated phenotypic changes in the absence of virus replication.

FIG. 4.

(A) Phenotype of C. parasitica p29 transformant strains. Strain EP155 was transformed with the p29 coding domains derived from wild-type (Twtp29), Cys(70) (TCys70), and Cys(72) (TCys72) mutant viruses. Each strain was grown on a PDA plate for 1 week and photographed. (B) Northern blot analysis of p29 transcripts isolated from transformants. Total RNA was isolated from representative transformant colonies (shown in panel A) containing wild-type (Twtp29), Cys70-Gly mutant (TCys70), and Cys72-Gly mutant (TCys72) p29 coding sequences. A transformant line with the p40 coding sequence (Tp40-1, a negative control) and a transfectant infected with wild-type CHV1-EP713 virus were also included in this analysis. Each well of the denaturing agarose gel was loaded with 20 μg of ssRNA, with the exception of the lane labeled CHV1-EP713, which received 0.5 μg of ssRNA. Transcripts derived from the introduced p29 sequences were probed with DIG-labeled PCR fragments spanning the p29 coding region (map positions 476 to 1250) and visualized by image processing of chemiluminescent signals. Ethidium bromide-stained 28S rRNA shown at the bottom of each lane served as a loading reference.

The observation that the p29Cys70-Gly mutant coding domain failed to alter host phenotype when expressed in transgenic lines was surprising given the very severe phenotypic changes caused by infection with the Cys(70) mutant virus (42). It is conceivable that the p29Cys70-Gly mutant protein requires other viral proteins to confer activity. To test this possibility, transformants containing the mutated p29 gene were transfected with Δp29. Infected transformants were examined for RNA accumulation levels and virus transmissibility as well as symptom severity. As shown in Fig. 5, no increased accumulation was observed for Δp29 genomic dsRNA in transformants containing the p29Cys70-Gly or p29Cys72-Gly coding domains (TCys70 and TCys72), whereas Δp29 RNA levels were elevated in wild-type p29 transformants (Twtp29) transfected in the same experiment. As described for Fig. 1A, internally deleted genomic dsRNAs (40), found in lanes Δp29/Twtp29, Δp29/TCys70, and Δp29/TCys72 (Fig. 5A), were quantified as genomic dsRNAs.

FIG. 5.

Effects of mutating the CHV1-EP713 p29 coding domain at cysteine residues 70 and 72 upon trans enhancement of viral genomic RNA accumulation. (A) Agarose gel electrophoretic analysis of total RNA isolated from Δp29 virus-infected C. parasitica strain EP155 that had been transformed with the coding domains of either wild-type p29 (Twtp29), p29Cys70-Gly substitution mutant (TCys70), or p29Cys72-Gly substitution mutant (TCys72). RNA isolated from untransformed EP155 uninfected (−) or infected with CHV1-EP713 wild-type virus (wt), Δp29, and Δp69b (Δp69) were analyzed in parallel. Equal amounts (0.2 OD units) of total RNA extracted from mycelia of each strain were electrophoresed through a 0.7% agarose gel in the 1× TAE buffer system (40 mM Tris-acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.8]) and stained with ethidium bromide. Multiple faster-migrating bands observed in the middle three lanes represent internally deleted genomic dsRNA (40). These defective dsRNA have never been found to be associated with any modulation of hypovirus-mediated symptoms. Lane M was loaded with the 1-kb ladder DNA size markers (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). Relative mobilities of viral dsRNAs are shown by an arrow at the left. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of viral negative-strand RNA purified from mycelia infected with wild-type or deletion mutant viruses. Total RNA was isolated from EP155 colonies infected with wt CHV1-EP713 and Δp29 and also from transformed mycelia expressing wt p29 (Twtp29), p29Cys70-Gly (TCys70), and p29Cys72-Gly (TCys72), which were each infected with Δp29. Viral negative-sense RNA in the total RNA preparations was semiquantitatively detected by real-time RT-PCR and normalized against 18S-rRNA, as in Fig. 1.

As expected from the failure of the p29 cysteine mutant proteins to enhance viral RNA levels (Fig. 5B), no significant increase was observed in Δp29 transmission in the p29Cys70-Gly or p29Cys72-Gly transformant (Table 2), rather a slight decrease was observed. This result contrasted with the doubling in transmission of Δp29 found for the wild-type p29 transformant (Table 2). Transgenic expression of the p29Cys70-Gly and p29Cys72-Gly mutant coding domains also had no effects on phenotypic alterations caused by the Δp29 mutant virus, resulting in a colony morphology indistinguishable from that of nontransformed EP155 infected with Δp29 virus (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

In trans effects of mutant p29 coding domains on symptoms caused by Δp29 infection. Transformed C. parasitica with the coding sequences of wild-type p29 (Twtp29), p29Cys70-Gly (TCys70), and p29Cys72-Gly (TCys72) were infected with the Δp29 mutant virus. These fungal colonies were grown on PDA for 1 week at bench top and photographed. Untransformed virus-free strain EP155 and Δp29- and CHV1-EP713-infected EP155 nontransformants were also cultured in parallel.

The combined results show that p29 residues Cys70 or Cys72 are required for in trans enhancement of Δp29 mutant virus genomic dsRNA accumulation and vertical transmission. Moreover, the fact that the mutation of these two cysteine residues results in both a loss of p29-mediated phenotypic changes (suppressed pigmentation and conidiation) in virus-free transformants and in trans complementation of Δp29 virus RNA accumulation and transmission suggests a possible linkage between the two functional activities.

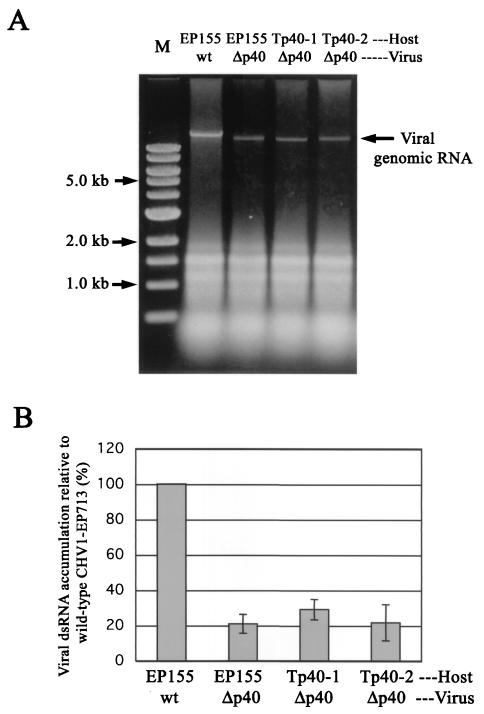

p40 expressed from fungal chromosomes failed to enhance viral genome accumulation, virus transmission, or phenotypic changes.

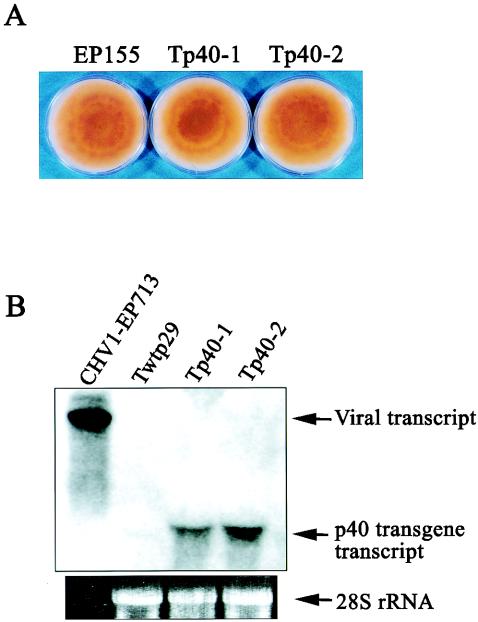

When expressed from the viral genome, the p40 coding domain was previously shown by a gain-of-function analysis (44) to be a contributor to the suppression of stromatal pustule formation and pigmentation caused by CHV1-EP713. This suppressive activity was also shown to correlated with the enhancement of viral genome accumulation. By using strategies similar to those used for analyzing p29 (16; the present study), we reexamined whether p40, like p29, could cause phenotypic changes independent of the effect on enhancing virus RNA accumulation and sought to determine whether the enhancement of viral RNA accumulation observed in cis could be reproduced in trans.

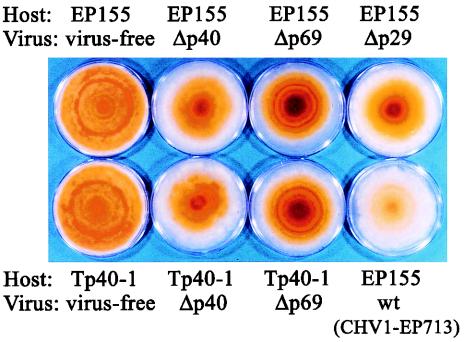

Examination of more than 10 independent p40 transformants revealed no phenotypic changes compared to untransformed EP155, confirming the report of Craven et al. (16). Two representative transformant lines (Tp40-1 and Tp40-2) are shown in Fig. 7A. The p40 transcript levels varied depending on strains and cultures (even from one single strain) and were generally lower than in C. parasitica colonies infected with CHV1-EP713 (Fig. 7B). These levels were, however, comparable to the p29 transcript levels present in the complementing transformant Twtp29 (Fig. 4B). These colonies were infected with Δp40 to determine whether p40 complemented the reduced RNA accumulation exhibited by the p40 deletion mutant virus. As shown in Fig. 8, Δp40 dsRNA was reduced to 20 to 25% relative to the wild-type virus RNA in untransformed strain EP155. Unlike the situation for p29 transformants, mutant viral RNA accumulation was not enhanced in the infected p40 transformants (Fig. 8). Similarly, virus transmission efficiency for Δp40 in the p40 transformants remained at a low level (Table 2). As shown in Fig. 9, p40 transformants infected by the Δp40 and Δp69 mutant viruses also exhibited symptoms similar to those caused by these viruses in untransformed strain EP155 (44). These combined results indicated that p40 cannot function in trans to complement virus-mediated phenotypic alterations or enhance viral RNA accumulation and transmission.

FIG. 7.

(A) Morphology of colonies transformed with the p40 coding domain. Spheroplasts of C. parasitica strain EP155 were transformed with plasmid pXH3 containing the p40 coding sequence (see Table 1). More than 10 independent transformant strains were obtained. Two representative strains, Tp40-1 and Tp40-2, cultured on PDA plates for 1 week at bench top are shown. Untransformed EP155 grown in parallel is also shown. (B) Northern blot analysis of the p40 transformant strains. ssRNA fractions prepared from mycelia of C. parasitica strain EP155 transformed with the p40 coding domain (Tp40-1and Tp40-2) and the p29 coding domain (Twtp29, a negative control) and from mycelia of strain EP155 transfected with hypovirus CHV1-EP713 were electrophoresed in a denaturing agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane sheet, and probed with DIG-labeled p40-encoding DNA fragments (map positions 1240 to 1780). The amount of RNA applied to each well was 20 μg for lanes Twtp29, Tp40-1, and Tp40-2 and 0.2 μg for lane CHV1-EP713. Ethidium bromide-stained 28S rRNA served as a loading reference.

FIG. 8.

Effects of in trans supply of p40 on viral genomic RNA accumulation. (A) Total RNA was isolated from mycelia of p40 transformants (Tp40-1 and Tp40-2) infected with a p40 mutant virus, Δp40b (Δp40), and electrophoresed in a 0.7% agarose gel as in Fig. 1A. Total RNA prepared from EP155 colonies infected with wild-type CHV1-EP713 (wt) and Δp40b was also applied to the same gel. Each lane was loaded with 0.25 OD units of total RNA and stained with ethidium bromide. The lane marked with M refers to 1-kb DNA ladder standards (NEB). (B) The viral dsRNA was semiquantified by real-time PCR analysis, as in the case for Fig. 1B.

FIG. 9.

Colony morphology of p40 transformants infected with deletion mutant viruses. Nontransformants (EP155) and transformants containing the p40 coding domain (Tp40-1), which were infected with wild-type (wt) or the deletion mutant virus strains Δp29 (Δp29), Δp40b (Δp40), and Δp69b (Δp69), were grown on PDA media for 1 week under benchtop conditions and then photographed. The virus-free colonies of two host strains, EP155 and Tp40-1, are also shown.

DISCUSSION

It is somewhat surprising that the independent deletion of either of the cleavage products derived from CHV1-EP713 ORF A-encoded polyprotein p69 results in reduced viral RNA accumulation and similar changes in host phenotype. The results presented here provide additional evidence that this apparent functional redundancy is mediated through different mechanisms and provides new insights into the relationship between viral RNA accumulation and viral RNA transmission. While p29 was shown to function in trans to complement deficiencies in mutant viral RNA accumulation and transmission exhibited by p29 deletion mutant viruses (Fig. 1 and 5 and Table 2), these enhancements were not observed in fungal colonies expressing p40 (Fig. 8 and Table 2). These results are consistent with the report by Craven et al. (16) that p29, but not p40, causes suppressed sporulation and reduced pigmentation when expressed in the absence of virus infection. The combined results support previous proposals that p29 alters host phenotype directly through action of the protein on host factors and indirectly by contributing to viral RNA accumulation, whereas p40 appears to alter host phenotype indirectly through an accessory role in amplifying viral RNA accumulation.

Additional differences have been observed in the magnitude of effects on sporulation and viral replication caused by deletion of the two coding domains. That is, under benchtop conditions Δp40-infected colonies produced much more conidia, approaching the levels of uninfected colonies, than Δp29-infected colonies, which show a 4- to 5-log reduction relative to uninfected colonies (44). Colonies infected with Δp40 accumulated less viral RNA (ca. 20% of wild-type virus) than Δp29-infected colonies (ca. 40% of wild-type virus). There are also significant differences in the predicted physical characteristics of the two proteins. p29 has a significant level of similarity to the multifunctional potyvirus papain-like protease protein HC-Pro (11, 27). These similarities include conserved amino acid sequences flanking the cysteine and histidine residues that are essential for proteolytic cleavage, the nature of the cleavage site, the distance between the essential residues and the cleavage site, and the conservation of a number of cysteine residues within the N-terminal portions of the two proteins. The C-terminal p69 cleavage product, p40, in contrast, is a highly basic protein (pKa 11.96) and does not share significant sequence similarity to entries in available protein databases (44; unpublished data). Comparisons of the mapped functional activity domains of p29 and p40 also fail to identify any obvious commonalities (42, 44).

The basis for the inability of p40 to enhance viral RNA accumulation when provided in trans (Fig. 8 and 9, Table 2), a function that has been clearly demonstrated when provided in cis in a gain-of-function assay (44), remains to be determined. It is conceivable that p40 function is dose dependent and that the p40 expression level in fungal transformants (Fig. 7B), which is lower than that in virus-infected colonies, is insufficient for activity. As a more likely alternative, p40 function may be highly cis preferential. In this regard, it has been previously proposed that p40 promotes expression of ORF B by facilitating ribosome termination and reinitiation at the UAAUG pentanucleotide that comprises the ORF A-ORF B boundary (44). The family Hypoviridae now consists of four species: CHV1, CHV2, CHV3, and CHV4 (22). CHV1 and CHV2 viruses, which have the dicistronic ORF A/ORF B genome architecture, both encode p40 homologues that share 30.2% amino acid sequence identity. In contrast, CHV3 and CHV4 viruses, which have monocistronic genomes, lack the p40 counterpart. Moreover, as previously reported by Suzuki and Nuss (44), all in vitro-engineered p40 deletion mutants of CHV1 that lacked the p40 activity domain in a dicistronic genome background underwent compensatory mutations that converted the genome organization from dicistronic to monocistronic. These combined observations have led to the suggestion that p40 functions in cis, perhaps cotranslationally, to enhance ORF B expression and thereby viral RNA replication by facilitating ribosome termination or reinitiation at the UAAUG pentanucleotide, ORF A-ORF B junction (44).

CHV1-EP713 p29 is a multifunctional protein with at least three functional domains. The N-terminal 24 codons are essential for virus viability, perhaps serving as part of an internal ribosome entry site-like sequence (43), whereas the C-terminal half, including the catalytic Cys162 and His215 residues, is responsible for the cotranslational self-cleavage from polyprotein p69 (11, 12). The third p29 domain was initially suggested from studies in which p29 was shown to suppress pigmentation and asexual sporulation regardless of whether it was expressed in the absence of virus infection or within the context of the infectious CHV1-EP713 cDNA clone, presumably through interactions with host factors (13, 16). Those studies also showed that the ability of p29 to modify phenotype was unrelated to its papain-like proteolytic activity. Suzuki et al. (42) subsequently mapped the p29 functional activity domain to a region extending from Gly25 through Gln73 and showed that two conserved cysteine residues within this region, Cys70 and Cys72, played an important role in the ability of p29 to alter host phenotype when expressed from the viral genome. The results of mutational analysis of these cysteine residues in the present study have several implications that require further testing.

Suzuki et al. (42) reported that substitution of Gly for p29 residues Cys70 and Cys72 resulted in viable viruses that caused quite different phenotypes; the Cys(72) mutant gave a phenotype indistinguishable from that of the Δp29 mutant virus, whereas the Cys(70) mutant virus caused a very severe, reduced growth phenotype. As expected from the mutant virus work, p29 containing the substitution mutation at Cys72 failed to suppress fungal pigmentation and conidiation or to enhance p29 mutant viral RNA accumulation when provided in trans (Fig. 4 and 5). Unexpectedly, the p29Cys70-Gly mutant also failed to cause phenotypic change or to complement Δp29 mutant virus RNA accumulation when expressed in transgenic fungal strains in the absence of virus. Moreover, these p29 cysteine substitution mutants failed to cause observable host phenotypic change even when the other viral proteins were furnished by infection with the Δp29 virus (Fig. 6) The failure of the p29Cys70-Gly and p29Cys72-Gly mutants to alter fungal phenotype or to enhance mutant viral RNA accumulation suggests that critical residues within the p29 activity domain, identified through an in cis, gain-of-function assay (42), are also required for the in trans functions of suppressing conidiation and pigmentation and enhancing viral RNA accumulation. These results also suggest a linkage between p29-mediated alteration of fungal phenotype in the absence of virus infection and the ability to complement deficiencies in p29 mutant virus RNA accumulation. Finally, the fact that the p29Cys70-Gly mutant causes a severe phenotype when provided in cis (42) but causes no phenotype when provided in trans, even after infection with Δp29 (Fig. 6), suggests the possibility of a cis-preferential functional interaction with another virus-encoded protein. This possibility is further supported by unpublished observations that the p29Cys70-Gly mutation also fails to confer a phenotype when provided from virus Cys70Δp40, a Δp40 deletion mutant containing the p29Cys70-Gly mutation (N. Suzuki and D. L. Nuss, unpublished results).

Viral transmission, whether horizontal through anastomosis or vertical through spores, is considered to be one of the key factors governing dissemination of hypovirulence and effective biological control of chestnut blight (1, 30). The rate of mycovirus transmission through conidia is influenced by interactions between virus isolates, host fungal stains, and culture conditions (19, 20). For example, the transmission efficiency of virus isolate CHV1-EP713 is 5% for infected fungal species C. radicalis and 86% for infected C. havanensis under benchtop conditions, and 100 and 66%, respectively, for the same fungal species under high light conditions (9). In contrast, many different CHV1 isolates are transmitted nearly at the same rate, 95 to 100% in different C. parasitica strains (33). The present study clearly indicates by loss-of-function and gain-of-function analyses that for CHV1-EP713, a viral protein, p29, enhances hypovirus transmission through conidia (Table 2). Further studies are required to determine whether virus-encoded protein-mediated enhancement of virus transmission holds for other hypovirus-host combinations. The results further suggest a direct correlation between viral RNA accumulation and transmission. Virus transmission frequencies for mutant virus RNAs Δp69, Δp40, and Δp29 (11 to 16%, 16 to 21%, and 48%, respectively; Table 2) correlate well with virus RNA accumulation levels in liquid-grown mycelia (10, 20, and 40% of wild-type levels, respectively) (Fig. 1) (44). Paradoxically, p29 both enhances viral RNA accumulation and transmission and decreases ecological fitness by suppressing production of conidia.

To our knowledge, the present study also contains the first measurement of hypovirus RNA in purified conidia and establishes a direct correlation between viral RNA transmission and viral RNA accumulation in asexual spores (Table 2 and Fig. 2). However, it remains unclear whether dsRNA levels in spores shown in Fig. 2 reflect dsRNA accumulation in a fraction of the purified conidia or whether the RNA is evenly distributed among all conidia in the population. In any event, there appears to be a direct correlation between the relative amounts of wild-type and mutant virus RNA in liquid-grown mycelia and in conidia. At the same time, for any given virus, there is a higher ratio of viral dsRNA to rRNA found in mycelia than in conidia (Fig. 2). These differences suggest the interesting possibility that a fungus may utilize an unknown mechanism to exclude viruses during conidogenesis, as is the case for plant virus accumulation in meristematic tissue (24). However, these latter considerations must be tempered by the inability to measure virus RNA accumulation in mycelia from which conida were directly derived due to technical difficulties in harvesting mycelia from PDA and from eliminating contaminating conida.

The mechanisms underlying the pleiotropic effects of p29-mediated cis and trans activities remains to be determined. p29-mediated phenotypic changes observed in the absence of virus infection must involve direct interactions with host components. The cis and trans complementation of reduced p29 mutant virus RNA accumulation and transmission could involve direct and/or indirect interactions with both host and viral components, e.g., the viral replicase, with the resulting increase in viral RNA then contributing to increased suppression of host conidiation and pigmentation. Interestingly, the papain-like leader protease (L-Pro) of beet yellows closterovirus (34-36) has also been reported to play a dispensable, but auxiliary, role in viral replication.

There is building circumstantial evidence to suggest that some of the observed p29-mediated effects are related to a role for p29 as a suppressor of a cellular posttranscriptional gene silencing (PTGS) antiviral defense response (25, 26, 41). This includes similarities between hypovirus p29 and the multifunctional potyvirus-encoded protein, HC-Pro, one of the first identified virus-encoded suppressors of PTGS (2, 26). In addition to the conserved N-terminal cysteines and papain-like protease catalytic and cleavage domains mentioned above, the two proteins also appear to alter host developmental processes when expressed in the absence of virus infection. That is, fungal transformants containing the p29 coding domain are compromised in asexual sporulation and exhibit morphological changes, including reduced levels of pigmentation (16) (Fig. 4; the present study), whereas Nicotiana benthamiana transformants containing the HC-Pro gene develop small tumors at their stem-root junctions (3). It is increasingly clear that many of the functional roles assigned to HC-Pro in viral genome amplification, vascular virus movement, and symptom severity are related to HC-Pro-mediated suppression of PTGS (25). Thus, it is tempting to predict that a similar relationship may be operating for p29. Potyviral HC-Pro can enhance the replication of heterologous viruses, e.g., cucumber mosaic cucumovirus, through suppression of PTGS (41). Continuing efforts to determine the effect of CHV1-EP713, and p29 specifically, on heterologous virus replication, PTGS and the accumulation of small interfering RNAs, a hallmark of PTGS (21) should confirm whether p29, like HC-Pro, functions as a suppressor of PTGS.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grant GM55981 to D.L.N. and a research grant from the Wesco Science Foundation to N.S.

We are grateful to Brad Hillman for fruitful discussions and to Chieko Suzuki for technical assistance. N.S. thanks Hideki Kondo, Tetsuo Tamada, and Hideaki Matsumoto for help with setting up a new sublaboratory at the Research Institute for Biosciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagnostakis, S. L. 1982. Biological control of chestnut blight. Science 215:466-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anandalakshmi, R., G. J. Pruss, X. Ge, R. Marathe, A. C. Mallory, T. H. Smith, and V. B. Vance. 1998. A viral suppressor of gene silencing in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:13079-13084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anandalakshmi, R., R. Marathe, X. Ge, J. M. Herr, Jr., C. Mau, A. Mallory, G. Pruss, L. Bowman, and V. B. Vance. 2000. A calmodulin-related protein that suppresses posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants. Science 290:142-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asamizu, T., D. Summers, M. B. Motika, J. V. Anzola, and D. L. Nuss. 1985. Molecular cloning and characterization of the genome of wound tumor virus: a tumor-inducing plant reovirus. Virology 144:398-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atreya, C. D., P. L. Atreya, D. W. Thornbury, and T. P. Pirone. 1992. Site-directed mutations in the potyvirus HC-PRO gene affect helper component activity, virus accumulation, and symptom expression in infected tobacco plants. Virology 191:106-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atreya, C. D., and T. P. Pirone. 1993. Mutational analysis of the helper component-proteinase gene of a potyvirus: effects of amino acid substitutions, deletions, and gene replacement on virulence and aphid transmissibility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:11919-11923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrington, J. C., S. M. Cary, T. D. Parks, and W. G. Dougherty. 1989. A second proteinase encoded by a plant potyvirus genome. EMBO J. 8:365-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, B., G. H. Choi, and D. L. Nuss. 1994. Attenuation of fungal virulence by synthetic infectious hypovirus transcripts. Science 264:1762-1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, B., C.-H. Chen, B. H. Bowman, and D. L. Nuss. 1996. Phenotypic changes associated with wild-type and mutant hypovirus RNA transfection of plant pathogenic fungi phylogenetically related to Cryphonectria parasitica. Phytopathology 86:301-310. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen, B., and D. L. Nuss. 1999. Infectious cDNA clone of hypovirus CHV1-Euro7: a comparative virology approach to investigate virus-mediated hypovirulence of the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica. J. Virol. 73:985-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi, G. H., D. M. Pawlyk, and D. L. Nuss. 1991. The autocatalytic protease p29 encoded by a hypovirulence-associated virus of the chestnut blight fungus resembles the potyvirus-encoded protease HC-Pro. Virology 183:747-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi, G. H., R. Shapira, and D. L. Nuss. 1991. Co-translational autoproteolysis involved in gene expression from a double-stranded RNA genetic element associated with hypovirulence of the chestnut blight fungus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:1167-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi, G. H., and D. L. Nuss. 1992. A viral gene confers hypovirulence-associated traits to the chestnut blight fungus. EMBO J. 11:473-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi, G. H., and D. L. Nuss. 1992. Hypovirulence of chestnut blight fungus conferred by an infectious viral cDNA. Science 257:800-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Churchill, A. C. L., L. M. Ciufetti, D. R. Hansen, H. D. Van Etten, and N. K. Van Alfen. 1990. Transformation of the fungal pathogen Cryphonectria parasitica with a variety of heterologous plasmids. Curr. Genet. 17:25-31. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craven, M. G., D. M. Pawlyk, G. H. Choi, and D. L. Nuss. 1993. Papain-like protease p29 as a symptom determinant encoded by a hypovirulence-associated virus of the chestnut blight fungus. J. Virol. 67:9513-9521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cronin, S., J. Verchot, R. Haldeman-Cahill, M. C. Schaad, and J. C. Carrington. 1995. Long-distance movement factor: a transport function of the potyvirus helper component proteinase. Plant Cell 7:549-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dawe, A. L., and D. L. Nuss. 2001. Hypoviruses and chestnut blight: exploiting viruses to understand and modulate fungal pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 35:1-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elliston, J. E. 1985. Preliminary evidence for two debilitating cytoplasmic agents in a strain of Endothia parasitica from western Michigan. Phytopathology 75:170-173. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enebak, S. A., W. L. MacDonald, and B. I. Hillman. 1994. Effect of dsRNA associated with isolates of Cryphonectria parasitica from the central Appalachians and their relatedness to other dsRNAs from North America and Europe. Phytopathology 84:528-534. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamilton, A. J., and D. C. Baulcombe. 1999. A novel species of small antisense RNA in post-transcriptional gene silencing. Science 286:950-952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hillman, B. I., D. W. Fulbright, D. L. Nuss, and N. K. Van Alfen. 2000. Hypoviridae, p. 515-520. In M. H. V. van Regenmortel et al. (ed.), Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses. Seventh report of the International Committee for the Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, San Diego, Calif.

- 23.Hillman, B. I., R. Shapira, and D. L. Nuss. 1990. Hypovirulence-associated suppression of host functions in Cryphonectria parasitica can be partially relieved by high light intensity. Phytopathology 80:950-956. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hull, R. 2002. Matthews' plant virology, 4th ed., p. 403-408. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 25.Kasschau, K. D., and J. C. Carrington. 1998. A counter-defensive strategy of plant viruses: suppression of post-transcriptional gene silencing. Cell 95:461-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasschau, K. D., S. Cronin, and J. C. Carrington. 1997. Genome amplification and long-distance movement functions associated with the central domain of tobacco etch potyvirus helper component-proteinase. Virology 228:251-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koonin, E. V., G. H. Choi, D. L. Nuss, R. Shapira, and J. C. Carrington. 1991. Evidence for common ancestry of a chestnut blight hypovirulence-associated double-stranded RNA and a group of positive-strand RNA plant viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:10647-10651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDonald, W. L., and D. W. Fulbright. 1991. Biological control of chestnut blight: use and limitation of transmissible hypovirulence. Plant Dis. 75:656-661. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maia, I. G., A.-L. Haenni, and F. Bernardi. 1996. Potyviral HC-Pro: a mutifunctional protein. J. Gen. Virol. 77:1335-1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nuss, D. L. 1992. Biological control of chestnut blight: an example of virus mediated attenuation of fungal pathogenesis. Microbiol. Rev. 56:561-576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nuss, D. L. 1996. Using hypoviruses to probe and perturb signal transduction processes underlying fungal pathogenesis. Plant Cell 8:1845-1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parsley, T. B., B. Chen, L. M. Geletka, and D. L. Nuss. 2002. Differential modulation of cellular signaling pathways by mild and severe hypovirus strains. Eukaryot. Cell 1:401-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peever, T. L., Y. C. Liu., P. Cortesi, and M. G. Milgroom. 2000. Variation in tolerance and virulence in the chestnut blight fungus-hypovirus interaction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4863-4869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng, C. W., and V. V. Dolja. 2000. Leader proteinase of the beet yellows closterovirus: mutation analysis of the function in genome amplification. J. Virol. 74:9766-9770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng, C. W., V. V. Peremyslov, A. R. Mushegian, W. O. Dawson, and V. V. Dolja. 2001. Functional specialization and evolution of leader proteinases in the family Closteroviridae. J. Virol. 75:12153-12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peremyslov, V. V., Y. Hagiwara, and V. V. Dolja. 1998. Genes required for replication of the 15.5-kilobase RNA genome of a plant closterovirus. J. Virol. 72:5870-5876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prasher, D. C., V. K. Eckenrode, W. W. Ward, F. G. Prendergast, and M. J. Cormier. 1992. Primary structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Gene 111:229-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saiki, R. K., D. H. Gelfand, S. Stoffe, S. J. Sharf, R. Higuchi, G. T. Horn, K. B. Mullis, and H. A. Erlich. 1988. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science 239:487-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 40.Shapira, R., G. H. Choi, B. I. Hillman, and D. L. Nuss. 1991. The contribution of defective RNAs to the complexity of viral-encoded double-stranded RNA populations present in hypovirulent strains of the chestnut blight fungus Cryphonectria parasitica. EMBO J. 10:741-746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi, X. M., H. Miller, J. Verchot, J. C. Carrington, and V. B. Vance. 1996. Mutational analysis of the potyviral sequence that mediates potato virus X/potyviral synergistic disease. Virology 231:35-42. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki, N., B. Chen, and D. L. Nuss. 1999. Mapping of a hypovirus p29 protease symptom determinant domain with sequence similarity to potyvirus HC-Pro protease. J. Virol. 73:9478-9484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki, N., L. M. Geletka, and D. L. Nuss. 2000. Essential and dispensable virus-encoded elements revealed by efforts to develop hypoviruses as gene expression vector. J. Virol. 74:7568-7577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki, N., and D. L. Nuss. 2002. The contribution of p40 to hypovirus-mediated modulation of fungal host phenotype and viral RNA accumulation. J. Virol. 76:7747-7759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thornbury, D. W., G. M. Hellmann, R. E. Rhoads, and T. P. Pirone. 1985. Purification and characterization of potyvirus helper component. Virology 144:260-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]