Abstract

We investigated the relationship between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) primary isolate (PI) antibody-mediated neutralization and attachment to primary blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). Incubation of PIs with immunoglobulin G (IgG) purified from infected patients did not inhibit attachment of the viruses with PBMC, but partial to complete neutralization was achieved. Neutralization of PIs already fixed on the cells was achieved by some IgG samples only and was of limited intensity compared to the former neutralization protocol. On the contrary, the binding of IgG to free virions was shown to be sufficient to reach potent neutralization, as the infectivity of IgG-PI complexes purified from the bulk of antibodies before addition to PBMC was strongly diminished compared to mock-treated controls. Monoclonal antibodies to the CDR2 domain of CD4 completely inhibited the infection of PBMC without interfering with the attachment of PIs to the cells, suggesting that, under these experimental conditions, the initial attachment of viruses to PBMC involves alternative cellular receptors. This initial interaction may also involve other components of the viral envelope than gp120, as partial depletion of the surface glycoproteins of primary viral particles that resulted in an almost complete loss of infectivity did not impair attachment to PBMC. A limited inhibition of attachment was observed when interfering with putative interactions with cellular heparan sulfate, whereas no effect was observed for cellular CD147 or nucleolin or for virion-incorporated cyclophilin A. Altogether, our results favor a mechanism of neutralization of HIV-1 PIs by polyclonal IgG where antibodies predominantly bind free virions and neutralize without interfering with the attachment to PBMC, which, in this model, is mainly CD4 independent.

The ability of neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) to prevent initial human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection has been recently demonstrated by passive transfer studies in monkeys (reviewed in reference 13). In addition, nAbs have been shown to be associated with the control of viremia in vaccinated CD8+-T-cell-depleted macaques (34) and in humans after interruption of highly active antiretroviral therapy (3, 24). The idea that an efficient vaccine against HIV should induce the humoral as well as the cellular immune response is therefore now widely accepted (7, 13, 23, 27). However, vaccination trials conducted up to now, as well as natural infections, only rarely resulted in the induction of an efficient neutralizing antibody response. Thus, there is a need for the rational elaboration of new immunogens able to elicit broadly functional nAbs. This objective is, however, still severely hampered by the limited available information with regard to specific characteristics of nAbs. The clarification of their mechanism(s) of action and the definition of the epitopes they recognize remain the main priorities in the perspective of HIV vaccine design.

Neutralization of HIV T-cell-line-adapted (TCLA) strains was shown to be mediated primarily by inhibition of virus-cell attachment when T-lymphocytic cell lines were used as targets (42, 44). The mechanism of neutralization might be different for HIV type 1 (HIV-1) primary isolates (PIs), as contradictory results were reported concerning the exact stage of the viral cycle that is impaired by nAbs. Indeed, despite an almost general agreement for an inhibition of virus entry, it is still unclear whether this occurs by preventing attachment of HIV to the target cell and/or through a subsequent blockade of the events leading to fusion. In a previous study performed in our laboratory, no significant decrease of the attachment of the HIV-1 PIs to primary blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) was observed when PIs were neutralized by immunoglobulin G (IgG) from infected patients and antibodies added after the time necessary to reach maximum virus adsorption on PBMC were still able to neutralize (42). On the contrary, Beirnaert et al. reported that the attachment of PIs to PBMC was reduced by some broadly neutralizing sera from patients (2). Other studies have proposed that cryptic epitopes, becoming accessible after the conformational changes of the viral glycoprotein induced by its interaction with the cellular receptor CD4, may be recognized by nAbs that broadly neutralize PIs (15, 36), thereby implying that neutralization may occur through antibodies that bind the virus after its attachment to the cell. Hence, the relative contributions of nAbs that bind exposed versus cryptic epitopes, as well as that of antibodies (Abs) that bind the virus before versus after its attachment to the cell, remain to be determined in the case of polyclonal nAb samples from infected patients.

HIV-1 entry occurs after sequential interactions of the virion with its cellular receptor CD4 and a coreceptor, namely CXCR4 or CCR5 for the majority of HIV-1 strains. However, an increasing number of studies suggest that the very initial attachment of the virus could be mediated by additional molecules, depending on the target cell. Intracellular adhesion molecule and leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 interaction has been reported to mediate attachment of HIV-1, with either intracellular adhesion molecule-1 (14) or leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 (19) being incorporated in the viral membrane and the other receptor acting as the cellular partner. Similarly, HLA-DR (9) and CD86 (5) incorporated in the viral membrane were shown to retain their functional ligand properties. Attachment of HIV-1 has also been reported to be mediated by cell-surface nucleolin (28). The cellular proteoglycan heparan sulfate (HS) was likewise shown to be responsible for the attachment of HIV-1 TCLA strains on lymphocytic (31, 35) and HeLa cell lines (22). HS was also reported to mediate attachment of a cloned HIV-1 PI to primary macrophages (38) but to have no effect on attachment of HIV to primary blood lymphocytes (18) or unstimulated PBMC (4). The attachment of HIV to cellular HS was shown to be mediated either by the V3 loop of gp120 (46) or by cyclophilin A (CypA) incorporated in the viral membrane (37). Virion-incorporated CypA has also been reported to mediate HIV-1 attachment to PBMC through an interaction with cellular CD147 (33, 40).

In this report, the initial attachment step of HIV-1 PI to PBMC, and its relationship with neutralization mediated by polyclonal IgG from infected patients was investigated. We first examined the ability of nAbs to inhibit virus infection when added before or after the virus has bound its target cell. We also assessed neutralization when IgG bound the free virion before the exposure of cryptic epitopes of the viral envelope protein was mediated by cellular receptor(s). We finally examined the contribution of the gp120-CD4 interaction and the involvement of alternative receptors in the initial attachment of HIV-1 PIs to PBMC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Production of virus stocks and purification of viral particles.

The PIs Bx08 (subtype B, R5) and Bx17 (subtype A, R5) were provided by H. Fleury. PI 11105C (subtype A, R5) was isolated from an infected individual from the Central African Republic in the laboratory of F. Barre-Sinoussi. All viruses were propagated once or twice, exclusively on freshly isolated PBMC (pooled from three donors, purified by Ficoll gradient, and phytohemagglutinin A [PHA] stimulated for 3 days), as previously described (25, 41). Viral stocks were obtained by collection of 24-h culture supernatants at the peak of virus production.

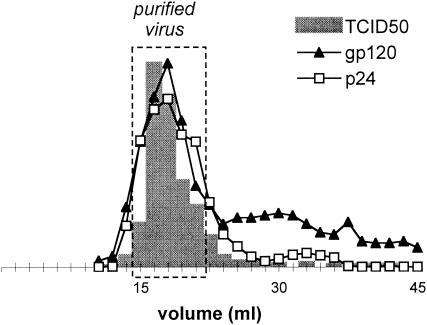

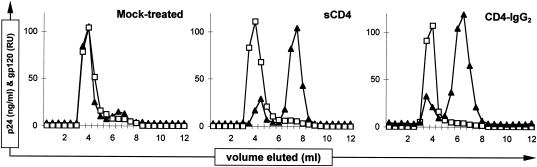

For some experiments, viruses were purified by a gel filtration method adapted from Moore et al. (26) to remove free p24 and gp120. Briefly, 5 ml of viral culture supernatant was loaded on Sephacryl S-1000 Superfine (Amersham) (35-ml gel bed for a 19-cm column length) and eluted by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The column was calibrated by titration of the infectious virus and dosage of viral proteins by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (see below) in the collected fractions. Figure 1 shows a representative elution profile obtained with PI Bx08. The majority of both p24 and gp120, which was excluded from the gel beads and eluted along with the infectious virus, corresponds to viral particle-associated proteins. Soluble proteins, including viral debris (shed gp120, gp120/gp160, and p24 from dying cells, etc.), were delayed and eluted in subsequent fractions. Five fractions corresponding to the virus-containing peak were pooled to obtain 7.5 ml of purified virus (Fig. 1), which was used in the following 3 h to minimize spontaneous particle degradation. The elution profile was controlled by performing a p24 ELISA on frozen aliquots of each fraction.

FIG. 1.

Purification of virus by gel filtration. The graph shows a representative elution profile of virus culture supernatant purification, which is intended to separate viral particles from debris. The presence of infectious PI Bx08 (grey bars) (peak value, TCID50 = 2,435 per ml) and viral proteins p24 (empty squares) (peak value, 793 ng/ml) and gp120 (black triangles) (relative units) was measured in the collected fractions. Five 1.5-ml fractions (dashed line) were pooled to obtain the purified virus sample.

The p24 concentrations of the virus culture supernatants used throughout this study were 732 ± 397 ng/ml for Bx08, 607 ± 252 ng/ml for Bx17, and 583 ± 191 ng/ml for 11105C. The corresponding purified virus samples obtained by gel filtration were diluted two- to threefold.

ELISAs.

The assay for p24 (Innotest; Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The dosage of gp120 was performed with a homemade ELISA, where the viral protein was captured on a 96-well plate (maxisorp ELISA plate; Nunc) through the anti-gp120 monoclonal Ab (MAb) D7324 (5 μg/ml for 12 h at 4°C in 50 mM bicarbonate buffer [pH 9.6]; Aalto, Dublin, Ireland). After a blocking step (PBS and 5% nonfat dry milk for 2 h at 37°C), the serum of an infected patient diluted 1/500 (1 h at 37°C) and a goat anti-human Ig polyclonal conjugate coupled to horseradish peroxidase (1 h at 37°C, diluted 1/5,000 in the blocking solution; Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Ala.) were successively incubated on the plate before the addition of the substrate (TMB; Pharmingen). As no autologous gp120 standards were available, relative gp120 concentrations were determined by using a recombinant glycoprotein (gp) of the TCLA strain MN, and as such, the results are expressed as relative units.

Sera, plasmas, purified IgG, MAbs, and proteins.

Large volumes of serum (100 ml) or plasma obtained by plasmapheresis (500 ml) (approval obtained from the Comité Consultatif pour la Protection des Personnes dans la Recherche Biomédicale) were collected from HIV-infected individuals. The mean duration of infection was 8.2 years (range, 2 to 17 years), and the mean CD4 count was 787 cells/mm3 (range, 459 to 1,168 cells/mm3) for the patients selected in this study. Sera collected from three seronegative donors were pooled and used as the negative control. All sera and plasmas were heat inactivated before use (30 min at 56°C). IgGs were purified from serum and plasma samples by protein A affinity chromatography as previously described (6, 42). Briefly, 5 ml of serum or plasma was loaded onto 10 ml of protein A-Sepharose 4B (Sigma), and the column was washed with 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7). Bound IgGs were eluted with 0.1 M glycine buffer (pH 2.7). The pH was immediately set back to neutrality, and fractions were filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (Costar). The efficacy and reproducibility of the purification were monitored by Ig subtype-specific ELISA, as previously described (6, 42). For all of the experiments, IgG sample dilutions refer to crude serum or plasma.

MAbs 2F5 and 2G12 were given by H. Katinger and provided by the European Union (EU) Programme EVA/MRC Centralized Facility for AIDS Reagents, National Institute for Biological Standards and Control (NIBSC), Potters Bar, United Kingdom (grant no. QLK2-CT-1999-00609 and GP828102). MAb b12 (IgG1b12) was given by D. Burton and P. Parren. Anti-CD4 MAbs Q4120 (ARP318; provided by Q. Sattentau), L120.3 (ARP359), 7.3F11, and 63G4 (ARP337 and ARP351, respectively; both provided by J. Habeshaw) were obtained through the EU Programme EVA/MRC Centralized Facility for AIDS Reagents, NIBSC. Q4120 binds to the CDR2 region of CD4 V1 domain (17) and has been shown to block attachment of HIV-1 TCLA strains to A3.01 (22, 44) and CEM (17) lymphoblastoid cell lines. 63G4 and 7.3F11 recognize the same region of CD4 as Q4120 and have been similarly shown to compete with soluble gp120 for binding to CD4 (17, 45). Anti-HS MAb (F58-10E4; Seikagaku) was purchased from Coger (Paris, France), anti-CypA rabbit antiserum was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology, and polyclonal goat anti-CD147 (EMMPRIN) extracellular domain was purchased from R&D Systems (33).

Soluble CD4 (sCD4) ARP609 (provided by Immunodiagnostics) was obtained through the EU Programme EVA/MRC Centralized Facility for AIDS Reagents, NIBSC. The CD4-IgG2 fusion protein (1), was provided by W. Olson and Progenics Pharmaceuticals. Recombinant human midkine (R&D Systems) was previously shown to inhibit binding of HIV-1 to HeLa cells (8).

Neutralization assay.

Two different neutralization assays were used. Our standard neutralization assay, which combines serial dilutions of antibodies with serial dilutions of virus, analyzes multiple rounds of infection on PBMC as previously described (6). Briefly, quadruplicate 25-μl aliquots of serial dilutions (twofold) of purified IgG were each incubated with 25 μl of serial dilutions of virus in prehydrated 96-well filter plates (1.25-μm pore size, Durapor Dv; Millipore, Molsheim, France). A control titration of the virus (25 μl of RPMI replacing the diluted IgG) was always performed on the same plate as the titrations in the presence of the IgG dilutions, as previously described (42). After 1 h at 37°C, 25 μl of PHA-stimulated PBMC at a concentration of 4 × 106 cells/ml (pool of PBMC from five healthy donors) was added to achieve a 75-μl final culture volume of RPMI, 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), and 20 IU of interleukin-2 (IL-2) per ml (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany). After 24 h at 37°C, 100 μl of the same culture medium was added. Two washings (200 μl of RPMI each) were performed by filtration on day 4 to remove the antibodies, and 200 μl of fresh culture medium was added. On day 7, the presence of p24 in the culture supernatants was measured by ELISA and compared to that of the negative controls (cultures infected with dilutions of virus and maintained in the presence of 10−6 M zidovudine [AZT]) to determine positive wells. Quadruplicate wells were used to determine the viral titer (50% tissue culture infective dose [TCID50]) in the absence (V0) and in the presence (Vn) of each dilution of the IgG. The neutralizing titer was defined as the dilution of antibodies resulting in a 90% decrease of the viral titer (Vn/V0 = 0.1).

A single round of infection assay was also used to determine both neutralization and attachment of a single sample in parallel. Briefly, PBMC were infected and washed as described for attachment experiments (see below), and p24 levels were measured by ELISA in the supernatants of aliquots of the samples cultured for 36 h at a density of 3.33 × 106 cells per ml. Neutralization is assessed by comparing the p24 released by PBMC infected in the presence of antibodies and in control infected cells. The high concentration of PBMC, intended to obtain high concentrations of p24 in the supernatant after 36 h, was found to not impair cell viability on that period (data not shown).

IgG-virus complexes and gp-120-depleted PIs: purification and neutralization.

Aliquots (500 μl) of purified virus were incubated with 500 μl of either purified IgG samples (final dilution, 1/10) for the formation of IgG-virion complexes or CD4-IgG2 (final concentration, 100 μg/ml) for the preparation of gp120-depleted PIs. After 90 min at 37°C, virus particles were separated from free IgG or gp120 by using gel filtration columns (as for virus purification, except that 1-ml samples were loaded on a 10-ml gel bed in a 21-cm-long column and 0.5-ml fractions were recovered). Samples obtained after the incubation of virus with CD4-IgG2 or IgG from infected patients were purified in parallel with a mock-treated control (virus incubated with either PBS or IgG from an uninfected individual), with up to 8 columns being run simultaneously. Aliquots of the fractions were frozen to monitor the gel filtration elution profiles by measuring the concentrations of p24, IgG, or gp120 with the corresponding ELISAs. Neither the incubation of PIs with the IgG samples nor incubation with sCD4 or CD4-IgG2 resulted in significant variations of the p24 concentrations in the virus particle-containing fraction after gel filtration, and for each experiment, the column fractions that were compared contained similar p24 levels (data not shown).

For the determination of neutralization of IgG-virus complexes, the gel filtration fractions were serially diluted (twofold) and quadruplicate aliquots (25 μl) of each dilution were incubated at 37°C with 25 μl of PHA-stimulated PBMC at a concentration of 4 × 106 cells/ml in filter plates. After 2 h, the plates were washed as for the standard neutralization assay, and the cells were cultured in complete medium for 7 days, with replacement of half the medium on day 4. Culture-positive wells were then determined by measurement of p24 by ELISA, and the TCID50 was determined for each fraction.

Attachment to PBMC.

The previously described protocol (42) was used to measure virus attachment to PBMC. Briefly, 250 μl of IgG was incubated for 1 h at 37°C with 250 μl of virus culture supernatant and then cooled for 5 min on ice. After the addition of 5 × 106 PBMC in 250 μl of cold RPMI, 10% FCS, and 20 IU of IL-2 per ml, samples were incubated for a further 2 h on ice. Unbound virus was removed by extensive washings (addition of 50 ml of cold RPMI, centrifugation, and removal of the supernatant, all done twice). These two washes efficiently eliminated unbound virus, as a third one was shown not to significantly modify the amount of p24 in the cell pellets (data not shown). After the first washing step, a pellet of PBMC infected with mock-treated virus was resuspended in 500 μl of trypsin (1× trypsin-EDTA; Eurobio) and incubated for 10 min at 37°C, and the removal of cell-associated p24 by the second wash assessed the extracellular localization of the virus. All cell pellets were resuspended in 750 μl of RPMI, 10% FCS, and 20 IU of IL-2 per ml. The virus attached to PBMC was quantified by performing a p24 ELISA on a first 250-μl aliquot of each sample while two other aliquots were transferred into a 48-well plate. The latter samples were cultured under normal conditions in a total volume of 500 μl of complete medium, with one supplemented with AZT to reach a final concentration of 10−6 M, and after 36 h of culture, neutralization and background p24 levels (cells treated with AZT) were determined by measuring p24 in the supernatants. Experiments performed in the presence of sulfate dextran, anti-CD11a, anti-CypA, cyclosporine, sCD4, and CD4-IgG2 were carried out under exactly the same conditions as those involving IgG samples. Attachment and neutralization were determined in the same way for gp120-depleted virus particles, except that 250 μl of these samples was directly incubated on ice with 250 μl of PBMC. For the experiments aimed at blocking putative cellular attachment receptors, anti-CD147 or midkine was preincubated for 1 h at 37°C with the PBMC and then cooled for 5 min on ice before the addition of virus and a further 2-h incubation on ice, with controls being made accordingly. For some experiments, PBMC (5 × 106 in 250 μl of RPMI) were pretreated with 20 U of heparinase I (Sigma) and 5 U of heparinase III (Sigma) for 2 h at 37°C and washed (50 ml of cold RPMI) before attachment experiments were performed.

As previously stated (42), we performed the association experiments at 4°C because we found more than 50% of cell-associated virus to be resistant to trypsin treatment after incubation of samples at 37°C. This indicates that viral entry had occurred, either by fusion and/or by endocytosis, with the later mechanism accounting for a large part of intracellular p24 at this temperature (20).

Postattachment neutralization.

To measure postattachment neutralization, PBMC were infected for 2 h on ice, as for attachment experiments, with RPMI replacing IgG. After the washing step, the cells were resuspended in 250 μl of RPMI before the addition of either 250 μl of diluted IgG samples or RPMI for controls. The cells were subjected to an additional 2-h incubation on ice and two further washings, intended to remove unbound IgG (experimental condition I). The cells were cultured for 36 h at 37°C in complete medium in the presence or absence of 10−6 M AZT before dosage of p24 to measure neutralization as for attachment experiments. These conditions were designed to allow the visualization of an eventual neutralization of previously attached virus, with the antibodies present only for a limited period of time corresponding to the estimated period needed for the PIs to mediate fusion at 37°C (42). In addition to these conditions, IgG samples were also preincubated for 1 h at 37°C with the PIs, added to the PBMC along with the virus, and present for the first incubation on ice and the cells were incubated with RPMI only for the second 2-h period on ice (experimental condition II). A third condition, where IgGs were both preincubated at 37°C and present for the first 2-h period on ice, and further added after the washings and present for the second 2-h incubation, was carried out to quantify the cumulated effect of the two previous conditions (experimental condition III).

RESULTS

Neutralization of HIV-1 PIs by IgG from patients.

The analysis of the neutralization of PIs Bx08, Bx17, and 11105C by serum and plasma samples collected from HIV-infected patients and by their purified IgG was previously reported (6). Those results, as well as those of neutralization experiments performed with additional samples (data not shown), have been used to select seven purified IgG samples from infected patients for this study. Neutralizing activities of those samples are summarized in Table 1. Purified IgG samples 4, 6, 8, 33, 35, and 44 were selected for displaying different neutralization spectra. Sample 3 was included as an infected individual control sample, which contains high levels of p24-specific and virus particle-binding IgG (R. Burrer, unpublished data) in the absence of any detectable neutralizing activity. Purified IgGs from the sera of seronegative individuals were included as HIV-negative controls. This selection complies with the previously determined relative sensitivities to neutralization of the PIs, with Bx08 being a relatively highly sensitive isolate and Bx17 and 11105C displaying intermediate profiles. The neutralizing activities of three standard neutralizing MAbs have been determined against these PIs. MAbs b12 and 2F5 were able to neutralize Bx08, Bx17, and 11105C. MAb 2G12 neutralized only Bx08 at the highest concentration tested.

TABLE 1.

Neutralization of PIs by purified IgG from sera and plasma from infected patients and MAbsa

| PI | Neutralizing titer of purified IgG sample:

|

IC90 (μg/ml) of MAb:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV− | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 33 | 35 | 44 | b12 | 2F5 | 2G12 | |

| Bx08 | — | — | 40 | 25 | 120 | 40 | 30 | 100 | 60 | 80 | 100 |

| Bx17 | — | — | 50 | — | — | 50 | 15 | 15 | 100 | 10 | — |

| 11105C | — | — | — | — | — | 20 | 10 | 40 | 60 | 20 | — |

Neutralization of HIV-1 PIs measured with the standard assay (see Materials and Methods) is expressed as the neutralizing titer (reciprocal of the dilution that results in a 90% decrease of the TCID50) for purified IgG samples or as the minimal concentration of MAb that induces the same loss of infectivity (90% inhibitory concentration [IC90]). —, neutralizing titer of <10 or IC90 of >100 μg of MAb/ml.

Neutralization and attachment.

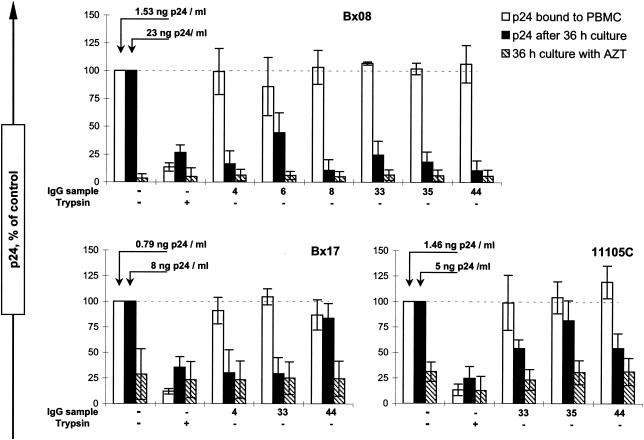

We next investigated the ability of neutralizing IgG samples to inhibit binding of HIV-1 PIs to PBMC. In the conditions set up to evaluate virus-cell attachment, the efficiency of neutralization of PI Bx08 or Bx17, measured by the decrease of p24 production compared to that of the control after 36 h of culture (Fig. 2), reflects the neutralizing titers measured by the standard method. Indeed, for the IgG samples that were shown to display neutralizing titers greater than 25 (Table 1), attachment experiments performed with IgG diluted 1/15 were found to result in comparable supernatant p24 levels after 36 h whether or not the culture was performed in the presence of AZT. A partial neutralization was obtained for IgG samples displaying neutralizing titers of 25 in the standard assay (Table 1, IgG sample 6 on Bx08), and the neutralization of Bx17 by sample 44 (Table 1, neutralizing titer 15) was not observed in the attachment assay. For virus 11105C, comparison between these two neutralization protocols is hampered by the low level of virus production at 36 h, with the amount of p24 released being only three times the background values obtained in the presence of AZT. Nevertheless, in both assays, IgG samples 33 and 44 have repeatedly higher neutralizing activities than sample 35. The fixation to PBMC of the PIs preincubated with the IgG was measured in parallel by quantification of cell-associated p24 after 2 h of interaction on ice and was found not to be significantly modified by the presence of any of the IgG samples (Fig. 2). Trypsin treatment of a control sample resulted in the removal of most cell-associated p24, assessing the efficacy of the washing procedure and the accessibility of the virus at the exterior of the cells (confirming that fusion and endocytosis did not occur at 4°C). These results extend our previous observations: polyclonal neutralizing IgGs do not prevent attachment of HIV-1 PIs to PBMC at 4°C.

FIG. 2.

Attachment of PIs to PBMC in the presence of neutralizing IgG from patients. The effect of IgG samples (diluted 1/15 compared to serum) on attachment of HIV-1 PIs Bx08, Bx17, and 11105C was determined after 2 h of incubation on ice. The attachment of the virus was measured as the p24 that remained associated to the cells after washings (empty bars). For each experiment, we added a sample treated with trypsin to confirm both the efficient removal of free virus by the washing procedure (the corresponding p24 levels should not be affected by protease treatment) and the extracellular localization of the PBMC-associated virus (cell-internalized virus becomes inaccessible to trypsin). Aliquots of each sample were cultured for 36 h at 37°C both in complete medium (black bars) and in complete medium supplemented with AZT (hatched bars) to assess neutralization and background p24, respectively. The results represent the means and standard deviations of the results of three independent experiments and are expressed as percentages of the positive controls. For these samples, the relative attachment and replication are 100% by definition, and the mean absolute p24 concentrations for attachment and replication are given above the corresponding bars.

Postattachment neutralization.

We next explored the possibility that antibodies neutralized HIV-1 PIs that were already attached to PBMC by adding IgG only after the removal of unbound virus (condition I). This postattachment neutralization was compared to the neutralizing activity when nAbs are able to act before, throughout, and for a limited period after virus attachment to PBMC (condition II) or when they are present for both the periods corresponding to conditions I and II (condition III). For the first dilution of IgG samples (1/15), condition II is similar to the experimental conditions of the attachment assay, except for the second incubation on ice and the additional washings. These supplementary operations did not modify the neutralizing activities, and all of the IgG samples that were neutralized in the attachment assay (Fig. 2) were shown to inhibit viral replication at least at the same IgG dilution (Fig. 3). Postattachment neutralization (Fig. 3) of Bx08 was detected for IgG samples 4, 8, and 44. However, the inhibition of p24 production did not exceed 50% for the 1/15 dilution of those IgG samples while no neutralization of previously attached virus was observed for samples 6 and 33. Experiments performed with Bx17 demonstrated an efficient postattachment neutralization by sample 4 while 50% neutralization of PBMC-bound Bx17 by IgG sample 33 was detected in one of three experiments. An additive effect of the neutralizing activities of the IgG during the two incubations on ice was observed for both PIs under condition III, where IgGs were present both before and after removal of unbound virus (Fig. 3). Indeed, the neutralization of Bx08 by the IgG samples capable of postattachment neutralization (samples 4, 8, and 44) was achieved at greater dilutions under condition III than under the two other conditions. An enhanced neutralization was also observed for IgG sample 6 on Bx08 under condition III compared to standard neutralization, although no detectable postattachment neutralization was mediated by this IgG sample. On the contrary, the prolonged incubations (condition III) of IgG sample 33 with both Bx08 and Bx17 and of IgG sample 4 with Bx17 did not result in an increase of neutralization compared to standard conditions, despite the potency of the postattachment neutralization that was detected in the last case.

FIG. 3.

Neutralization of PBMC-bound PIs by purified IgG from infected patients. Postattachment neutralization was determined by adding the IgG only after 2 h of adsorption of HIV-1 PIs to PBMC on ice, where free virus was removed before the addition of Abs for 2 h at 4°C (experimental condition I) (squares). In parallel, IgGs were also preincubated with the virus and present during virus-cell attachment at 4°C, before being removed together with the viral inoculum (experimental condition II) (triangles), and in experimental conditions III, the IgGs were present throughout the entire experiment (circles). Virus replication was assessed by p24 measured in the culture supernatant in the absence (solid line) or presence (dashed) of AZT as indicated in Materials and Methods. Each value corresponds to the mean of the results of two or three independent experiments.

It is of note that the dosage of cell-associated p24 was performed for each sample in the postattachment neutralization assays in the same way as for attachment experiments and that no significant decrease of PBMC-bound PI compared to the control was detected in the presence of IgG (data not shown). This result shows that the postattachment neutralization that was detected is not the consequence of an antibody-mediated dissociation of cell-associated virus but rather occurs through a blocking of a step of the viral cycle that is subsequent to the initial attachment of the virus to the cell.

These experiments show that the neutralization by polyclonal IgG from patients, which do not inhibit attachment of HIV-1 PIs to PBMC, is not mainly achieved by Abs that block infection by cell-associated virus. Postattachment neutralization is indeed of limited efficacy and is restricted to a fraction of the IgG samples. These results thus suggest that, despite the absence of virus-cell attachment impairment, neutralization may have been primarily achieved by IgG that had bound virions before their interaction with the target cell.

Neutralization of IgG-virion complexes.

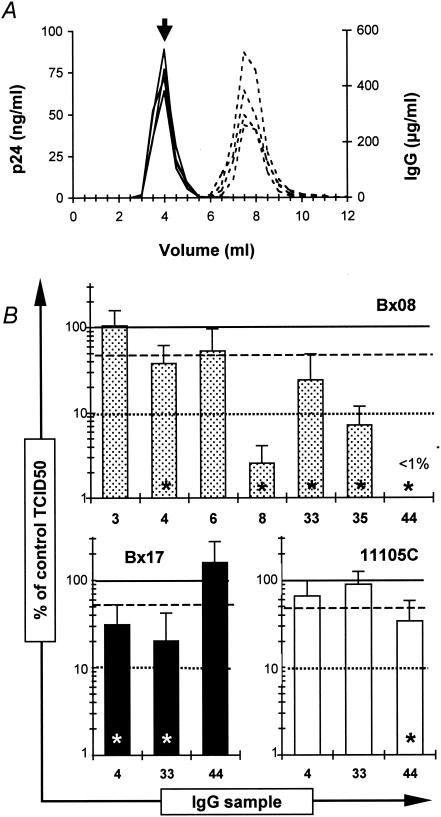

We therefore evaluated the ability of polyclonal IgG to neutralize PIs before the conformational modifications of the viral envelope glycoproteins that result from the attachment of the virus to its cellular receptor(s). To reach that purpose, it was necessary to separate IgG-bound virions from the bulk of antibodies before addition to the target cell. Purified virus was thus incubated with antibodies, and IgG-coated viral particles were separated from free IgG by gel filtration (Fig. 4A). The TCID50 of gel filtration-purified IgG-virus complexes obtained with IgG samples from infected individuals were compared to that of virus incubated with purified IgG from a seronegative individual (Fig. 4B). For PI Bx08, incubation with IgG samples 4 and 33 resulted in 62 and 76% mean losses of infectivity compared to the mock-treated control, respectively, whereas IgG-virus complexes obtained with samples 8 and 35 had lost more than 90% of their infectivity (TCID50). In the case of Bx08 complexed with IgG from sample 44, 100% neutralization was achieved, as no well positive for viral replication was evidenced in three independent experiments. A more than 65% decrease in TCID50 was achieved for PI Bx17 in complex with IgG from samples 4 and 33 and for PI 11105C and IgG from sample 44. The overall match between the neutralization obtained in the standard assay (Table 1) and the titration of the IgG-virus complexes (Fig. 4B) was good, with samples displaying neutralizing titers ranging from 40 to 50 or from 100 to 120 in the standard neutralization assay showing TCID50 diminutions of between 50 and 90% or greater than 99%, respectively, with the second method. The only exception is IgG sample 35, which leads to more than 90% inhibition of the infectivity of Bx08-IgG complexes while having an intermediate neutralizing titer of 30 in the standard assay. Titration of MAb-virus complexes obtained after incubation of Bx08 with b12 or 2G12 at 100 μg/ml did not result in any significant decrease of the TCID50 compared to that of the control (data not shown). However, a 50% inhibition of infectivity was achieved in two independent experiments by incubating b12 at a final concentration of 500 μg/ml with purified Bx08 (data not shown). This may appear to be an unusually high concentration, but it is noteworthy that the correspondence between the levels of neutralization detected in the standard neutralization assay and the reduction of infectivity of the IgG-virion complexes is quite comparable for b12 and polyclonal IgG. Indeed, as neutralizing titers of 40 to 50 (Table 1) of polyclonal samples in the standard assay correspond to 50% neutralization of IgG-virion complexes after being incubated at a final dilution of 1/10, on the basis of a steady relation between the tests, the 60-μg/ml 90% inhibitory concentration of b12 for PI Bx08 (Table 1) can be predicted to require a final concentration of 240 to 300 μg/ml to reduce the infectivity of b12-Bx08 complexes by 50%. The 500-μg/ml b12 concentration required to observe this inhibition is in fact only slightly higher than the calculated value.

FIG. 4.

Purification and measurement of the infectivity of IgG-virion complexes. (A) Antibodies complexed to viral particles, obtained by incubating purified virus with IgG samples at a dilution of 1/10, were separated from free IgG by gel filtration. The figure shows the representative elution profiles of 4 columns performed in parallel, with the dosage of p24 (plain lines) and IgG (dashed lines) concentrations in each fraction. (B) The fractions corresponding to the peak of p24 (arrow on panel A) were titrated on PBMC. Infectivity is expressed as the percentage of the TCID50 of each sample compared to that of the mock-treated control, with all the samples being tested in parallel with the same purified virus preparation for a given PI (i.e., up to 8 columns in parallel). Each value corresponds to the mean and standard deviation of the results of three independent experiments. Lines indicate 0% (solid), 50% (—), and 90% (.....) inhibition of infectivity. Stars denote statistically significant reductions in TCID50 (Student test, P = 0.05).

It is of note that the neutralization of the PI by our IgG samples is unlikely to have occurred because of antibody-induced shedding of the gp120. Indeed, we neither found significant differences in the gp120 concentrations of virus particle-containing fractions treated with either nAbs, non-nAbs, and control IgG nor detected gp120 in the subsequent column fractions that would have been predicted to contain the shed gp120 protein (data not shown).

These results indicate that the binding of neutralizing polyclonal IgG from infected patients to free viral particles is sufficient to result in an effective neutralization of HIV-1 PIs.

Involvement of the gp120-CD4 interaction in the initial attachment of PIs to PBMC.

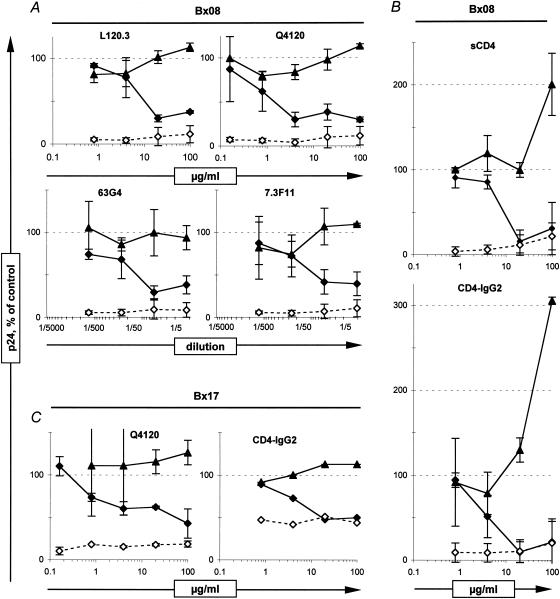

We next analyzed whether the attachment of PIs to PBMC observed in this study was dependent on the interaction of the viral envelope gp120 subunit with the cellular CD4. For that purpose, we either blocked the CD4 on target PBMC with anti-CD4 MAbs or preincubated the virus with sCD4 or CD4-IgG2 before performing neutralization and virus-cell attachment experiments. All four of the anti-CD4 MAbs tested were shown to completely inhibit Bx08 replication, at least when incubated at 100 μg/ml (Fig. 5A). This neutralization was, however, not associated with any detectable decrease of the attachment of PIs to PBMC, as expected for the CD4 fourth domain-specific MAb L120.3 but also for Q4120, 63G4, and 7.3F11, which bind the CDR2 region of CD4 domain 1. Neutralization without inhibition of attachment was also observed after incubation of Bx17 with Q4120-treated PBMC (Fig. 5C, left panel). Moreover, incubation of PIs with sCD4 or CD4-IgG2 at 100 μg/ml resulted in a complete inhibition of viral replication, together with an increase of virus attachment to PBMC for Bx08 (Fig. 5B), whereas no detectable modification of the attachment of Bx17 to the PBMC was detected (Fig. 5C, right panel). Altogether, these experiments are in accordance with a requirement of the gp120-CD4 interaction to reach productive infection but strongly suggest that the initial attachment of HIV-1 PIs to PBMC detected in our experiments occurs independently of CD4.

FIG. 5.

Attachment and neutralization of HIV-1 PIs in the presence of anti-CD4 MAbs, sCD4, and CD4-IgG2. Bx08 (A and B) and Bx17 (C) neutralization (diamonds) and attachment to PBMC (triangles) were measured under conditions where the PBMC were preincubated with anti-CD4 MAbs (A and C, left) or where the virus was preincubated with sCD4 or CD4-IgG2 (B and C, right). Each value corresponds to the mean and standard deviation of the results of at least two independent experiments, except for CD4-IgG2 with Bx17, which was performed only once. Cultures of samples in the presence of 10−6 M AZT (dashed line, open diamonds) give background p24 values for neutralization.

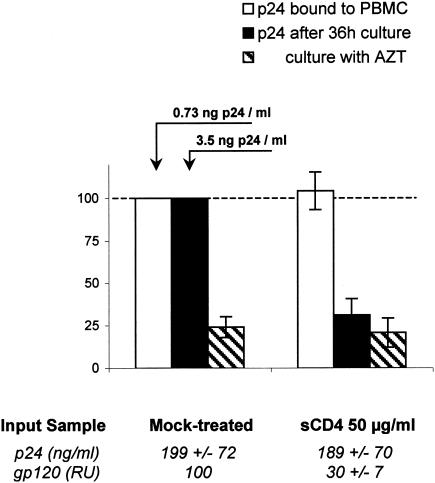

As sCD4 is known to induce HIV-1 gp120 shedding, we investigated whether this specific mechanism was involved in the neutralization of the virus and whether the loss of the gp120 would impair the ability of primary viral particles to bind to PBMC. We thus separated viral particles from free proteins by gel filtration after incubation of purified virus with sCD4 or CD4-IgG2. Contrary to the control, where little spontaneous shedding was observed (Fig. 6, left panel), incubation of Bx08 with sCD4 or CD4-IgG2 at 50 μg/ml resulted in an important loss of gp120 by viral particles, with the surface gp being eluted apart from virus particles (Fig. 6, center and right panels). Attachment experiments were performed with Bx08 virus particles that had lost part (65 to 75%) of their gp120 as a result of incubation with sCD4. Although these gp120-depleted viruses had completely lost their infectivity (no significant production of p24 compared to cultures maintained in the presence of AZT) (Fig. 7), their ability to bind PBMC was not altered compared to mock-treated infectious virus (Fig. 7). These results demonstrate that shedding of gp120 contributes to the neutralization of Bx08 mediated by sCD4 and CD4-IgG2, with the residual gp120 possibly blocked by a competition mechanism. The conserved attachment of viral particles that have lost a fraction of gp120 high enough to result in almost complete neutralization could reflect the requirement of a lower number of intact gp or spikes to mediate attachment of the virus to PBMC than to complete entry. On the other hand, it may also indicate the involvement of alternative virus-associated molecules in the initial attachment of HIV-1 PIs to PBMC.

FIG. 6.

sCD4 and CD4-IgG2 induce the shedding of Bx08 gp120. Purified virus was incubated with PBS (mock-treated control, left panel) or 50-μg/ml sCD4 (central panel) or CD4-IgG2 (right panel) for 1 h at 37°C, and viral particles were further purified by parallel gel filtration columns. Dosage determinations for the viral proteins p24 (empty squares) and gp120 (black triangles) in the collected fractions were performed as indicated in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 7.

Attachment and neutralization of gp120-depleted viral particles. Bx08 culture supernatant was incubated with PBS (mock-treated control) or 50-μg/ml sCD4 for 1 h at 37°C, and viral particles were purified by gel filtration as previously described. The fraction corresponding to the first peak of p24 (Fig. 6) was used to determine the attachment to PBMC (empty bars), neutralization (black bars), and background p24 after culture in the presence of AZT (hatched bars). The p24 and gp120 concentrations were measured in the fractions that were used for the attachment experiment (bottom values) to assess the content in viral particles and the extent of shedding of the samples to be compared. The data correspond to the means and standard deviations of the results of two independent experiments.

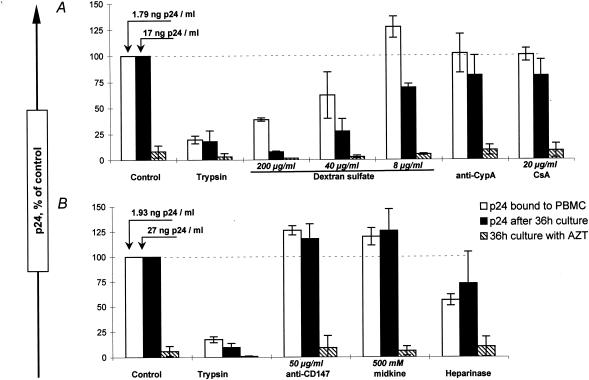

Role of alternative HIV-1 attachment receptors.

Preincubation of the virus with dextran sulfate at concentrations of 8 to 200 μg/ml resulted in partial to almost complete inhibition of viral replication paralleled by decreased attachments of the PIs to PBMC (Fig. 8A), indicating a possible involvement of HS as an alternative cellular receptor in this model. Expression of HS by PBMC was not detectable by flow cytometry, contrary to the P4R5 cell line, for which a high HS expression level was detected (data not shown). Heparinase treatment of PBMC, however, resulted in a mean 44% decrease of Bx08 attachment compared to control untreated PBMC, with a concomitant inhibition of viral replication detected in two of three experiments (Fig. 8B). Neutralization and attachment experiments were performed by adding Bx08 preincubated with IgG samples to heparinase-treated PBMC. The results obtained were comparable to those of the experiments performed with untreated PBMC, with the PI neutralized by the IgG samples without any detectable inhibition of the attachment to heparinase-treated PBMC compared to the corresponding control (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Attachment of HIV-1 PIs in the presence of blocking reagents to putative alternative attachment interactions. The role of alternative cellular receptor candidates and virion-incorporated molecules in the initial attachment of PI Bx08 to PBMC was investigated. Experiments were performed either by preincubation of the virus with various potential attachment-blocking factors, at concentrations previously reported to efficiently inhibit attachment in some virus-cell models, before addition to the cells (A) or by preincubation of the cells with the reagents before addition of the virus (B), with controls made accordingly. Data correspond to the means and standard deviations of the results of at least two independent experiments.

We then investigated the possibility that other factors previously reported to mediate HIV attachment are involved in the PI-PBMC model. We similarly investigated the role of CypA in the attachment by incubating either the virus with an antiserum to CypA or with CsA (Fig. 8A) or the target cells with an antibody to CD147 (Fig. 8B) and likewise obtained attachment and virus replication levels comparable to those of the controls. Finally, no involvement of cell surface nucleolin in the attachment of Bx08 to PBMC was detected, as preincubation of the cells with its natural ligand midkine did not result in any diminution of attachment or infectivity (Fig. 8B).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the contribution to neutralization of polyclonal Abs that bind HIV-1 PIs before or after the attachment of the virus to PBMC. Our results show that although the attachment of HIV-1 PIs to PBMC is not inhibited by polyclonal neutralizing IgG at 4°C, neutralization of cell-associated virus is achieved only by a subset of the IgG samples and is of limited efficiency compared to neutralization by Abs preincubated with the virus before addition to the cells. It appears, on the contrary, that neutralization is mainly mediated by Abs that bind the free viral particle, as binding of neutralizing IgG to the virus in the absence of the cells results in an effective blocking of infectivity of purified IgG-virus complexes. Our results also strongly suggest that, at least under these experimental conditions, the initial attachment of HIV-1 PIs to PBMC is not primarily mediated by the gp120-CD4 interaction and that additional molecules on both the cellular and viral membranes may contribute to this event.

In a previous study, it was shown that the neutralization of HIV PIs by IgG purified from serum samples from infected patients collected shortly after seroconversion was not associated with an inhibition of the attachment of the PIs to PBMC (42). We show here that a similar outcome is obtained with purified IgG from long-term-infected patients. On the contrary, Beirnaert et al. reported a concomitant neutralization and inhibition of binding of HIV PIs to the PBMC by some broadly cross-neutralizing sera from infected patients while samples of a more-restricted spectrum were neutralized in the absence of any inhibition of the attachment (2). In our hands, this correlation between broad-spectrum neutralization and inhibition of attachment was not observed, as the IgG samples 33 and 35 that neutralize the three PIs included in this study and also the highly neutralization-resistant PI Kon (subtype A, X4) (6), did not inhibit the attachment of neutralized PIs to PBMC. Whether the decrease of attachment reported by Beirnaert et al. is due to the higher temperature used (37°C instead of 4°C) or whether it originates from the biological materials used remains to be further assessed.

As our results indicated that attachment was not inhibited by polyclonal neutralizing IgG, we sought to evaluate the neutralization that occurs through Abs binding to cell-associated viruses. The attached virus was shown to be partially accessible to neutralization by some of the IgG samples tested while no postattachment neutralizing activity was detected for some other IgG samples. The ability to neutralize postattachment was apparently not associated with the neutralization determined with the standard assay, as samples 4 and 33 neutralized both Bx08 and Bx17 with comparable titers (Table 1) while sample 4 was able to neutralize after virus attachment and sample 33 was not. In a similar manner, no apparent relationship was detected between cross-neutralization and postattachment neutralization (sample 33 has a greater neutralization spectrum than sample 8 but does not exhibit postattachment neutralization) (Table 1). We also examined the potential cumulative effect of standard and postattachment neutralization. An additive effect was observed for the IgG samples that were able to neutralize cell-associated virus and also for two IgG samples that did not mediate a detectable postattachment neutralization, suggesting that the IgG may need to be present for a prolonged period of time to neutralize cell-associated virus. It was previously shown that at 37°C efficient neutralization of PIs Bx17 and Bx26 by autologous sera was achieved when IgGs were added to PBMC 1 h after the virus, with attachment of PIs to PBMC being maximal after 20 min at both 4 and 37°C, whereas neutralization of Bx26 by a heterologous serum was only partial under these conditions (42). Whether the potency of this postattachment neutralization was a characteristic of these two sera, whether it is a feature of autologous neutralization, or whether it was due to the shorter virus-cell incubation time before the addition of IgG than that used in the present study remains to be further investigated. Altogether, our results indicate that postattachment neutralization represents a minor proportion of the neutralization mediated by polyclonal IgG from infected patients, at least at 4°C and for the PI-PBMC model. After attachment, steric hindrance certainly restricts the accessibility of the viral surface that points toward the target cell, thus limiting the opportunity for postattachment neutralization. Consistent with this hypothesis, it has been reported that MAbs to CD4-induced epitopes, which very efficiently neutralized a TCLA strain that had been preincubated with subinhibitory concentrations of sCD4, displayed a drastic decrease of their neutralizing activities when the epitopes they recognize are exposed as a result of virus-cell receptor contact (43).

It has nevertheless been proposed that cryptic, CD4-induced epitopes could be crucial targets for nAbs (15, 36). We have conversely investigated the possibility that neutralization occurs through binding of Abs to epitopes that are accessible on virions in the absence of receptor-mediated conformational modifications of the envelope glycoproteins. Our results show that IgG-virion complexes obtained with IgG samples previously identified as neutralizing have at least partly lost their infectivity, contrary to those obtained with nonneutralizing IgG samples, indicating that nAbs were able to bind their specific epitopes in the absence of cell-virus interactions. It implies that these epitopes were exposed on the free virus particle, either at first or, possibly, as a consequence of triggering the conformational changes that make them accessible by another cluster of partner-acting IgG. The decreases in TCID50 observed in this test were proportional to the neutralizing titers that were determined with our standard neutralization assay, except for that for one IgG sample. Given the difference in the extent of neutralization of free and PBMC-associated virus, it appears that polyclonal IgG from patients could bind to circulating HIV-1 PIs and efficiently neutralize the virus, although the contribution of antibodies recognizing epitopes elicited by virus-cell interactions cannot be excluded. Experiments performed under conditions where binding of gp120 to CD4 was inhibited suggest that another virus-cell interaction(s) mediates HIV-1 PI attachment to PBMC. Indeed, the CD4-specific MAbs Q4120, 7.3F11, and 63G4, which target the gp120-binding domain, completely inhibited infection despite a total absence of inhibition of PI attachment to PBMC. We cannot completely exclude the possibility that a partial blocking of CD4 by CDR2-specific MAbs may result in inhibition of fusion while having a limited effect on attachment because the number of gp120-CD4 interactions required for fusion should exceed that needed for attachment. However, as neutralization of Bx08 by Q4120 was still effective at a concentration of 5 μg/ml, it seems very unlikely that no inhibition of attachment, even partial, would have been observed when a 20-fold-higher concentration of Q4120 was used if CD4 was the only cellular attachment receptor. Thus, these results very strongly suggest that, under our experimental conditions, the initial attachment of PIs to PBMC involves alternative receptors, with the interaction with CD4 still absolutely required at a subsequent stage of the entry process. A complete inhibition of the infection without inhibition of the attachment by Q4120 was similarly observed in a HeLa CD4+ cell model by Mondor et al., and HS was found to act as an attachment receptor in this model (22). Moreover, McInerney and Dimmock reported that the same anti-CDR2 MAb very efficiently mediated postattachment neutralization of an HIV-1 PI on PBMC (21), a result that would be consistent with the existence of alternative attachment receptors. It has also been shown that HIV-1 PIs are able to bind to CD4+ and CD4-depleted PBMC to a similar extent (29). Altogether, these data suggest that an interaction(s) in addition to gp120 binding to CD4 may mediate the attachment of PIs to PBMC.

We found that the presence of either sCD4 or CD4-IgG2 at 4°C resulted in the neutralization of the PIs, although it had no effect on the attachment of Bx17 to PBMC nor did it lead to an increase of the attachment in the case of Bx08. Demaria et al. previously reported that incubation of TCLA strain IIIB with sCD4 results in an increased attachment of the virus to H9 cells (11, 12). These authors proposed that the increase of attachment is limited by the amount of gp120-sCD4 complexes that remains associated with gp41 on the viral surface (12). This hypothesis would explain the absence of attachment enhancement that was observed in the experiments where Bx08 incubated with sCD4 was further purified by exclusion chromatography, as this step could result in the dissociation of most virus-associated sCD4.

Purified Bx08 virus particles bearing about 30% of the initial gp120 were able to bind PBMC to the same extent as the mock-treated control, despite having almost completely lost their infectivity. Again, the lower number of gp120-CD4 interactions required for attachment than for fusion may result in the blocking of the entry of incompletely gp120-depleted virus particles at a step posterior to CD4-mediated attachment. However, the fact that we did not observe any decrease, even limited, of the attachment of the gp120-depleted virus particles to PBMC in these experiments could also reflect the existence of an interaction(s) that involve(s) other virion-incorporated molecules different from surface glycoprotein. Indeed, some studies have reported the ability of envelope-free retrovirus-like particles (16, 32, 39) to bind their target cells, with the attachment being mediated by cellular HS in at least one case (16). Moreover, it has been shown that envelope-free HIV-1 was able to productively infect various CD4+ and CD4− cell lines, with the authors proposing a mechanism of entry that would be mediated by virion-incorporated cellular proteins and the appropriate receptor on the target cell (10, 30). We have, however, not been able to further reduce the concentration of gp120 on virus particles, and additional experiments are required to address the question of its requirement for the attachment of HIV-1 PI to PBMC.

As our results indicate that the initial interaction between the PIs and the PBMC may involve alternative factors both at the cellular and viral surfaces, we performed experiments to explore an eventual implication of some previously described candidate molecules. We found that the presence of dextran sulfate resulted in a diminution of both the replication and attachment of a PI to PBMC, with this inhibition indicating a possible attachment of the virus through cellular glycosaminoglycans. The attachment of HIV-1 to HS has been reported in several studies, either through an interaction with the gp120 V3-loop (22, 35, 46) or through cellular CypA incorporated into the viral membrane (37). Other reports previously showed a preponderant role of HS for the attachment of HIV-1 PIs to macrophages (38) but no involvement of HS for the infection of primary blood lymphocytes (18) or unstimulated PBMC (4) by HIV-1 PIs. We find here that although the expression of HS by PHA-stimulated PBMC was under detectable levels by flow cytometry, experiments performed with heparinase-treated PBMC resulted in a mean 45% decrease of the attachment of the PI compared to untreated cells, favoring the implication of HS in a fraction of the initial attachment of PIs to PBMC. It is of note that heparinase treatment provoked a parallel reduction of the attachment and of the virus replication, indicating that the binding of HIV-1 PI to HS on PBMC is followed by a productive infection. Whether it is a direct infection of the cell that bears the HS receptor or an infection in trans remains to be determined. No inhibition of the attachment was detected when interfering with putative interactions through cellular CD147 and nucleolin or virion-incorporated CypA, suggesting that these molecules are not involved in the initial binding of our PIs to PBMC. Finally, as CD4 was required to reach productive infection in our experiments, a direct attachment to the coreceptor is a very unlikely mechanism for the infection of PBMC by our PIs.

In conclusion, our results indicate that the initial attachment of PIs to PBMC is mediated by alternative interactions along with the binding of gp120 to CD4 and that this attachment step is predominantly CD4 independent. Our data also support a model where neutralization of HIV-1 by polyclonal IgG is not primarily achieved by inhibition of the initial attachment step but rather by preventing some subsequent event(s). In this model, some nAbs are still able to bind the virion after its attachment to the cell and to inhibit viral replication, but such a postattachment neutralization appears to be a limited phenomenon. Effective or even total neutralization is, on the contrary, achieved by the binding of polyclonal IgG samples to free virus particles. These nAbs bound to free virions do not interfere with an initial CD4-independent attachment of PIs to PBMC but rather inhibit the subsequent obligate interactions between the viral glycoprotein and the CD4 receptor and/or the coreceptor.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the ANRS and by a grant from the EU (QLK2-CT-1999-01321 “Eurovac”). R.B. was supported by a grant from “Ensemble contre le SIDA.”

REFERENCES

- 1.Allaway, G. P., K. L. Davis-Bruno, G. A. Beaudry, E. B. Garcia, E. L. Wong, A. M. Ryder, K. W. Hasel, M. C. Gauduin, R. A. Koup, J. S. McDougal, et al. 1995. Expression and characterization of CD4-IgG2, a novel heterotetramer that neutralizes primary HIV type 1 isolates. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 11:533-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beirnaert, E., S. De Zutter, W. Janssens, and G. G. van der Groen. 2001. Potent broad cross-neutralizing sera inhibit attachment of primary HIV-1 isolates (groups M and O) to peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Virology 281:305-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binley, J. M., A. Trkola, T. Ketas, D. Schiller, B. Clas, S. Little, D. Richman, A. Hurley, M. Markowitz, and J. P. Moore. 2000. The effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on binding and neutralizing antibody responses to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 182:945-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanco, J., J. Barretina, A. Gutierrez, M. Armand-Ugon, C. Cabrera, B. Clotet, and J. A. Este. 2002. Preferential attachment of HIV particles to activated and CD45RO+CD4+ T cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 18:27-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bounou, S., N. Dumais, and M. J. Tremblay. 2001. Attachment of human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) particles bearing host-encoded B7-2 proteins leads to nuclear factor-kappa B- and nuclear factor of activated T cells-dependent activation of HIV-1 long terminal repeat transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 276:6359-6369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burrer, R., D. Salmon-Ceron, S. Richert, G. Pancino, G. Spiridon, S. Haessig, V. Roques, F. Barre-Sinoussi, A. M. Aubertin, and C. Moog. 2001. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgA, but also nonantibody factors, account for in vitro neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 primary isolates by serum and plasma of HIV-infected patients. J. Virol. 75:5421-5424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton, D. R., and J. P. Moore. 1998. Why do we not have an HIV vaccine and how can we make one? Nat. Med. 4:495-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callebaut, C., S. Nisole, J. P. Briand, B. Krust, and A. G. Hovanessian. 2001. Inhibition of HIV infection by the cytokine midkine. Virology 281:248-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantin, R., J. F. Fortin, G. Lamontagne, and M. Tremblay. 1997. The presence of host-derived HLA-DR1 on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 increases viral infectivity. J. Virol. 71:1922-1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chow, Y. H., D. Yu, J. Y. Zhang, Y. Xie, O. L. Wei, C. Chiu, M. Foroohar, O. O. Yang, N. H. Park, I. S. Chen, and S. Pang. 2002. gp120-independent infection of CD4(-) epithelial cells and CD4(+) T-cells by HIV-1. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 30:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demaria, S., S. A. Tilley, A. Pinter, and Y. Bushkin. 1995. Bathophenanthroline disulfonate and soluble CD4 as probes for early events of HIV type 1 entry. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 11:127-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demaria, S., and Y. Bushkin. 1996. Soluble CD4 induces the binding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to cells via the V3 loop of glycoprotein 120 and specific sites in glycoprotein 41. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 12:281-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrantelli, F., and R. M. Ruprecht. 2002. Neutralizing antibodies against HIV—back in the major leagues? Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14:495-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortin, J. F., R. Cantin, G. Lamontagne, and M. Tremblay. 1997. Host-derived ICAM-1 glycoproteins incorporated on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are biologically active and enhance viral infectivity. J. Virol. 71:3588-3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fouts, T., K. Godfrey, K. Bobb, D. Montefiori, C. V. Hanson, V. S. Kalyanaraman, A. DeVico, and R. Pal. 2002. Crosslinked HIV-1 envelope-CD4 receptor complexes elicit broadly cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies in rhesus macaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:11842-11847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guibinga, G. H., A. Miyanohara, J. D. Esko, and T. Friedmann. 2002. Cell surface heparan sulfate is a receptor for attachment of envelope protein-free retrovirus-like particles and VSV-G pseudotyped MLV-derived retrovirus vectors to target cells. Mol. Ther. 5:538-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healey, D., L. Dianda, J. P. Moore, J. S. McDougal, M. J. Moore, P. Estess, D. Buck, P. D. Kwong, P. C. Beverley, and Q. J. Sattentau. 1990. Novel anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies separate human immunodeficiency virus infection and fusion of CD4+ cells from virus binding. J. Exp. Med. 172:1233-1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibrahim, J., P. Griffin, D. R. Coombe, C. C. Rider, and W. James. 1999. Cell-surface heparan sulfate facilitates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry into some cell lines but not primary lymphocytes. Virus Res. 60:159-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liao, Z., J. W. Roos, and J. E. Hildreth. 2000. Increased infectivity of HIV type 1 particles bound to cell surface and solid-phase ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 through acquired adhesion molecules LFA-1 and VLA-4. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 16:355-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marechal, V., F. Clavel, J. M. Heard, and O. Schwartz. 1998. Cytosolic Gag p24 as an index of productive entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 72:2208-2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McInerney, T. L., and N. J. Dimmock. 2001. Postattachment neutralization of a primary strain of HIV type 1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells is mediated by CD4-specific antibodies but not by a glycoprotein 120-specific antibody that gives potent standard neutralization. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 17:1645-1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mondor, I., S. Ugolini, and Q. J. Sattentau. 1998. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 attachment to HeLa CD4 cells is CD4 independent and gp120 dependent and requires cell surface heparans. J. Virol. 72:3623-3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montefiori, D. C., and T. G. Evans. 1999. Toward an HIV type 1 vaccine that generates potent, broadly cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:689-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montefiori, D. C., T. S. Hill, H. T. Vo, B. D. Walker, and E. S. Rosenberg. 2001. Neutralizing antibodies associated with viremia control in a subset of individuals after treatment of acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 75:10200-10207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moog, C., H. J. Fleury, I. Pellegrin, A. Kirn, and A. M. Aubertin. 1997. Autologous and heterologous neutralizing antibody responses following initial seroconversion in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J. Virol. 71:3734-3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore, J. P., J. A. McKeating, R. A. Weiss, and Q. J. Sattentau. 1990. Dissociation of gp120 from HIV-1 virions induced by soluble CD4. Science 250:1139-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nabel, G. J. 2001. Challenges and opportunities for development of an AIDS vaccine. Nature 410:1002-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nisole, S., B. Krust, and A. G. Hovanessian. 2002. Anchorage of HIV on permissive cells leads to coaggregation of viral particles with surface nucleolin at membrane raft microdomains. Exp. Cell Res. 276:155-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olinger, G. G., M. Saifuddin, M. L. Hart, and G. T. Spear. 2002. Cellular factors influence the binding of HIV type 1 to cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 18:259-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pang, S., D. Yu, D. S. An, G. C. Baldwin, Y. Xie, B. Poon, Y. H. Chow, N. H. Park, and I. S. Chen. 2000. Human immunodeficiency virus Env-independent infection of human CD4− cells. J. Virol. 74:10994-11000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel, M., M. Yanagishita, G. Roderiquez, D. C. Bou-Habib, T. Oravecz, V. C. Hascall, and M. A. Norcross. 1993. Cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan mediates HIV-1 infection of T-cell lines. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 9:167-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pizzato, M., S. A. Marlow, E. D. Blair, and Y. Takeuchi. 1999. Initial binding of murine leukemia virus particles to cells does not require specific Env-receptor interaction. J. Virol. 73:8599-8611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pushkarsky, T., G. Zybarth, L. Dubrovsky, V. Yurchenko, H. Tang, H. Guo, B. Toole, B. Sherry, and M. Bukrinsky. 2001. CD147 facilitates HIV-1 infection by interacting with virus-associated cyclophilin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:6360-6365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rasmussen, R. A., R. Hofmann-Lehmann, P. L. Li, J. Vlasak, J. E. Schmitz, K. A. Reimann, M. J. Kuroda, N. L. Letvin, D. C. Montefiori, H. M. McClure, and R. M. Ruprecht. 2002. Neutralizing antibodies as a potential secondary protective mechanism during chronic SHIV infection in CD8+ T-cell-depleted macaques. AIDS 16:829-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roderiquez, G., T. Oravecz, M. Yanagishita, D. C. Bou-Habib, H. Mostowski, and M. A. Norcross. 1995. Mediation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 binding by interaction of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans with the V3 region of envelope gp120-gp41. J. Virol. 69:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salzwedel, K., E. D. Smith, B. Dey, and E. A. Berger. 2000. Sequential CD4-coreceptor interactions in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Env function: soluble CD4 activates Env for coreceptor-dependent fusion and reveals blocking activities of antibodies against cryptic conserved epitopes on gp120. J. Virol. 74:326-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saphire, A. C., M. D. Bobardt, and P. A. Gallay. 1999. Host cyclophilin A mediates HIV-1 attachment to target cells via heparans. EMBO J. 18:6771-6785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saphire, A. C., M. D. Bobardt, Z. Zhang, G. David, and P. A. Gallay. 2001. Syndecans serve as attachment receptors for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 on macrophages. J. Virol. 75:9187-9200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma, S., A. Miyanohara, and T. Friedmann. 2000. Separable mechanisms of attachment and cell uptake during retrovirus infection. J. Virol. 74:10790-10795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherry, B., G. Zybarth, M. Alfano, L. Dubrovsky, R. Mitchell, D. Rich, P. Ulrich, R. Bucala, A. Cerami, and M. Bukrinsky. 1998. Role of cyclophilin A in the uptake of HIV-1 by macrophages and T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1758-1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spenlehauer, C., S. Saragosti, H. J. Fleury, A. Kirn, A. M. Aubertin, and C. Moog. 1998. Study of the V3 loop as a target epitope for antibodies involved in the neutralization of primary isolates versus T-cell-line-adapted strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 72:9855-9864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spenlehauer, C., A. Kirn, A. M. Aubertin, and C. Moog. 2001. Antibody-mediated neutralization of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates: investigation of the mechanism of inhibition. J. Virol. 75:2235-2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sullivan, N., Y. Sun, J. Binley, J. Lee, C. F. Barbas III, P. W. Parren, D. R. Burton, and J. Sodroski. 1998. Determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein activation by soluble CD4 and monoclonal antibodies. J. Virol. 72:6332-6338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ugolini, S., I. Mondor, P. W. Parren, D. R. Burton, S. A. Tilley, P. J. Klasse, and Q. J. Sattentau. 1997. Inhibition of virus attachment to CD4+ target cells is a major mechanism of T cell line-adapted HIV-1 neutralization. J. Exp. Med. 186:1287-1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilks, D., L. Walker, J. O'Brien, J. Habeshaw, and A. Dalgleish. 1990. Differences in affinity of anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies predict their effects on syncytium induction by human immunodeficiency virus. Immunology 71:10-15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang, Y. J., T. Hatziioannou, T. Zang, D. Braaten, J. Luban, S. P. Goff, and P. D. Bieniasz. 2002. Envelope-dependent, cyclophilin-independent effects of glycosaminoglycans on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 attachment and infection. J. Virol. 76:6332-6343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]