Abstract

Background

Lower activated partial thromboplastin times are associated with higher levels of some coagulation factors and may represent a procoagulant tendency.

Methods

In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, we studied the 13-year risk of venous thromboembolism in relation to baseline activated partial thromboplastin time in 13,880 individuals. We also studied 258 venous thromboembolism cases and 589 matched controls with measurements of additional coagulation factors.

Results

Adjusting for demographics and procoagulant factors reflected in the activated partial thromboplastin time (fibrinogen, factors VIII, IX, XI, and von Willebrand factor), participants in the lowest two quartiles of activated partial thromboplastin time compared with the fourth quartile had 2.4-fold (95% CI 1.4, 4.2) and 1.9-fold (95% CI 1.1, 3.2) higher risks of venous thromboembolism. The risk associated with activated partial thromboplastin times below the median was higher for idiopathic (OR 5.5; 95% CI 2.0, 15.5) than secondary venous thromboembolism (OR 1.74; 95% CI 0.88, 3.43). Subjects with both activated partial thromboplastin times below the median and factor V Leiden were 12.6-fold (95% CI 5.7, 28.0) more likely to develop venous thromboembolism compared to those with neither risk factor (p-interaction <0.01). A lower activated partial thromboplastin time also added to the thrombosis risk associated with obesity and elevated D-dimer.

Conclusions

A single determination of the activated partial thromboplastin time below the median increased the risk of future venous thromboembolism. Findings were independent of coagulation factor levels, and a low activated partial thromboplastin time added to the risk associated with other risk factors.

The activated partial thromboplastin time is commonly used for detection of coagulation factor deficiencies1. Three studies in selected populations suggested shorter partial thromboplastin times were associated with increased risk of venous thromboembolism2-4. These studies analyzed partial thromboplastin times measured after the venous thromoembolism event3, 4 or at the time of thrombosis in hospitalized patients2.

An association of lower activated partial thromboplastin times with thrombosis could be explained by increased activity of coagulation factors in the intrinsic or common pathways or resistance to activated protein C2, 3, 5. Inherited6 and acquired7, 8 elevation of factor VIII activity (a key determinant of activated partial thromboplastin times) are also associated with thrombosis risk. No long-term prospective studies have evaluated the effect of low activated partial thromboplastin times on the incidence of future venous thromboembolism accounting for coagulation factors and heritable thrombosis risk factors.

In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort, we studied the relationship of baseline activated partial thromboplastin times and incidence of venous thromboembolism over thirteen years. We hypothesized that a low baseline activated partial thromboplastin time would be associated with a higher incidence of venous thromboembolism, independent of coagulation factor levels measured using this test. To address clinical utility, we evaluated for supra-additive associations of the activated partial thromboplastin time and other thrombosis risk factors.

Materials and Methods

Cohort

The Longitudinal In Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology (LITE)9 is a study of venous thromboembolism risk factors in the ARIC Study10 and the Cardiovascular Health Study11 (prospective multi-center cohort studies). As activated partial thromboplastin times were not measured in the Cardiovascular Health Study; this report reflects data from ARIC only. ARIC enrolled 15,792 participants aged 45-64 between 1987-1989 in four US communities10. The baseline examination included extensive risk factor collection, including self-reported race and phlebotomy.

Event Ascertainment

Participants were contacted annually by telephone and seen every 3 years (<5% lost to follow-up). Hospitalizations were identified by participant or proxy reports or by reviews of local hospital discharge lists12. Medical records from participants with hospital discharge codes for venous thromboembolism were reviewed. Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolus were defined using standardized criteria12 and classified as secondary if preceded within 90 days by major trauma, surgery, marked immobility, or associated with active cancer or chemotherapy9.

Activated partial thromboplastin times were measured on all participants. For additional laboratory analyses, we used baseline samples from a nested case-control study of participants who had incident venous thromboembolism through December 31, 2002 and controls who were frequency-matched to cases by age (within 5 years), sex, race (non-white, white), and follow-up time (case event date within 2 years of an assigned date for controls).

Laboratory Analysis

Blood was drawn at baseline after an 8 hour fast and plasma stored at -70°C10, 13. The activated partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen, factor VIII coagulant activity (factor VIIIc), von Willebrand factor, and protein C were measured in a central laboratory in all participants. Activated partial thromboplastin times were measured on an automated coagulometer (Coag-A-Mate X-2, General Diagnostics; rabbit brain phospholipid reagent, General Diagnostics) with a reliability coefficient of 0.9213, 14. Fibrinogen was measured using the thrombin time titration method and factor VIIIc measured by assessing clotting time after adding factor VIII deficient plasma (reliability coefficients 0.72 and 0.86 respectively)13, 14. Protein C and von Willebrand factor were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbant assays (ELISA) from American Bioproducts Co (reliability coefficients 0.56 and 0.68, respectively)13, 14. In the nested case-control study, factors IX and XI were measured by ELISA (Enzyme Research Laboratories) and D-dimer by automated immunoturbidometric assay (STA-R instrument, Liatest D-Di, Diagnostica Stago). Blood group genotypes, factor V Leiden and prothrombin 20210A mutations were detected using standard techniques among 98.3% of participants who consented for genetic testing15.

Statistical Analysis

Participants who were not white or black were excluded (n=103) as this sample was too small for analysis. Participants reporting prebaseline venous thromboembolism (n = 276), cancer (n = 871), warfarin use (n = 87), or with missing data for the activated partial thromboplastin time (n = 285) were excluded. Participants in the top 2.5% of activated partial thromboplastin times (≥35.6 seconds, n = 341) were excluded to minimize any effect of lupus anticoagulants on associations, leaving an analysis cohort of 13,880. The nested case-control study included 258 cases and 589 controls.

Some analyses could be run on the entire cohort, and results from both the entire cohort and the nested case-control study are reported. Mean values or prevalence of thrombosis risk factors at baseline according to activated partial thromboplastin time quartiles were compared using ANOVA for continuous variables and logistic regression for dichotomous variables. P-values for trend were calculated using the median value of each activated partial thromboplastin time quartile. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for freedom from thrombosis by activated partial thromboplastin time quartile were examined.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to study the association of activated partial thromboplastin times and venous thromboembolism in the entire cohort. Model 1 was adjusted for age, gender, race, field-center, and body mass index. Model 2 assessed mediating by coagulation factors in the intrinsic and common pathways. (factor VIIIc, fibrinogen, and von Willebrand factor). In the nested case-control study, analogous logistic regression models were run, with model 2 adjusted additionally for factor VIIIc, factor IX, factor XI, fibrinogen, and von Willebrand factor. In the nested case-control study we assessed the impact of factor V Leiden, prothrombin 20210A, ABO genotype, protein C, and D-dimer by adding them individually to Model 1. As the lower two activated partial thromboplastin time quartiles were associated with thrombosis risk, we used activated partial thromboplastin times below the median to define abnormal for subgroup analyses. Stratified logistic regression models were run based on race (white vs. non-white), gender, and type of thrombosis event (idiopathic vs. secondary, and deep venous thrombosis vs. pulmonary embolus) adjusted for Model 2 covariates in the nested case-control sample. We evaluated additive interactions of risk factors using age, gender, and race-adjusted models by cross-classifying participants based on activated partial thromboplastin times above or below the median and obesity, factor VIIIc (top quartile vs. bottom 3 quartiles), ABO genotype (O vs. non-O), D-dimer (above or below the median), factor V Leiden, and prothrombin 20210A (presence or absence). For each factor, the relative excess risk proportion over what would be seen in an additive model of two risk factors alone was calculated16.

Results

During a median of 13.1 years of follow-up (174,519 person-years), there were 260 first-time venous thromboembolism events (1.49 per 1000 person-years); 111 idiopathic, 179 diagnosed as deep venous thrombosis and 81 as pulmonary embolism with or without deep venous thrombosis. Two cases denying consent for DNA studies were excluded from nested case-control analyses.

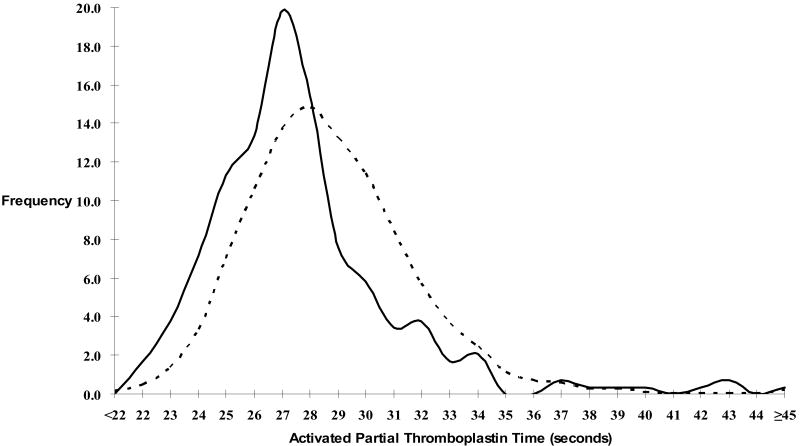

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics by activated partial thromboplastin time quartile. Increasing age, female gender, body-mass index, factor VIIIc, von Willebrand factor, protein C, and hormone replacement therapy use, but not race or fibrinogen, were associated with lower activated partial thromboplastin times. For the nested case-control study analytes, higher factors IX and XI, and non-O blood group were associated with lower activated partial thromboplastin times, with no association with D-dimer, factor V Leiden, or prothrombin 20210A. In the full cohort, cases had lower activated partial thromboplastin times than non-cases (27.7s vs. 28.9s, p < 0.001) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics According to Quartile of Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time

| Characteristic | Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Quartile | p for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Full Cohort (n) | 3,491 | 3,509 | 3,352 | 3,528 | |

| Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (s) | 21.1 - 27.0 | 27.1 – 28.7 | 28.8 – 30.5 | 30.6 – 35.5 | |

| Age (years) | 54.8 | 54.2 | 53.7 | 53.5 | <0.001 |

| Gender (n, % women) | 2,171 (62.2) | 1,996 (56.9) | 1,719 (51.3) | 1,683 (47.7) | <0.001 |

| Race (n, % black) | 977 (28.0) | 881 (25.1) | 831 (24.8) | 1,007 (28.5) | 0.51 |

| Body-Mass Index (kg/m2) | 28.6 | 27.7 | 27.4 | 27.1 | <0.001 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 305 | 302 | 302 | 302 | 0.08 |

| Factor VIIIc (%) | 158 | 134 | 124 | 112 | <0.001 |

| von Willebrand Factor (%) | 141 | 120 | 111 | 100 | <0.001 |

| Protein C (ug/mL) | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Women on Hormone Replacement (n, %) | 433 (20.8) | 401 (20.8) | 282 (16.9) | 289 (17.8) | 0.004 |

|

| |||||

| Nested Case-Control Study (Controls Only, n) | 141 | 148 | 145 | 155 | |

| Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (s) | 21.1 - 27.0 | 27.1 – 28.7 | 28.8 – 30.5 | 30.6 – 35.5 | |

| Age (years) | 56.2 | 56.1 | 55.9 | 55.5 | 0.25 |

| Gender (n, % Women) | 92 (65.3) | 87 (58.8) | 76 (52.4) | 72 (46.5) | <0.001 |

| Race (n, % Black) | 43 (30.5) | 38 (25.7) | 39 (26.9) | 64 (41.3) | 0.03 |

| Body-Mass Index (kg/m2) | 28.9 | 27.8 | 28.3 | 27.2 | 0.02 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 315 | 306 | 307 | 307 | 0.43 |

| Factor VIIIc (%) | 160 | 134 | 125 | 113 | <0.001 |

| Factor IX (%) | 148 | 139 | 140 | 134 | <0.001 |

| Factor XI (%) | 150 | 135 | 132 | 128 | <0.001 |

| von Willebrand Factor (%) | 143 | 123 | 114 | 102 | <0.001 |

| D-dimer (ug/mL) | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.59 |

| Protein C (ug/mL) | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.0 | <0.001 |

| Women on Hormone Replacement (n, %) | 18 (19.6) | 13 (14.9) | 14 (18.4) | 19 (26.4) | 0.24 |

| Blood Group non-O (%) | 85 (63.0) | 90 (65.2) | 69 (49.6) | 60 (40.5) | <0.001 |

| Factor V Leiden (%) * | 8 (5.8) | 2 (1.4) | 3 (2.2) | 4 (2.7) | 0.20 |

| Prothrombin 20210A (%) * | 2 (1.5) | 7 (5.0) | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 0.21 |

Heterozygotes and homozygotes

Figure 1. Distribution of Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Among Cases (Solid Line) and Non-cases (Dashed Line) (Full Cohort).

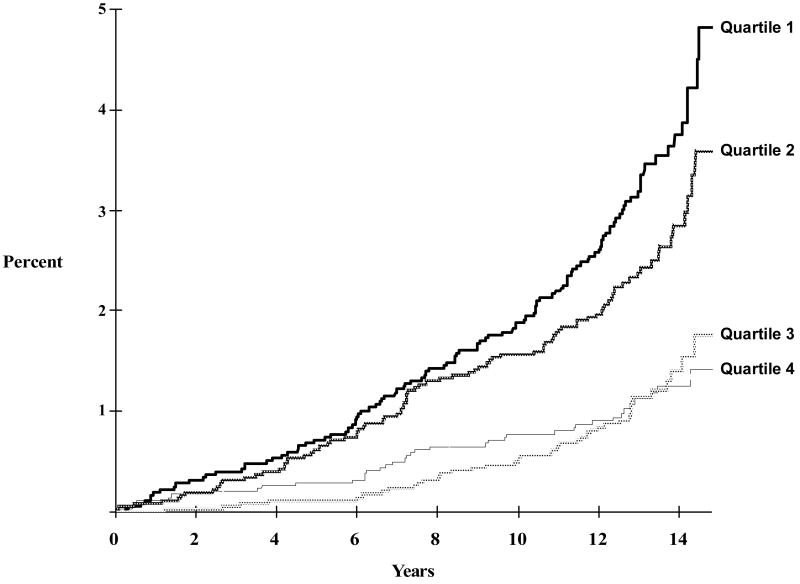

In the full cohort the incidence of venous thromboembolism was 2.5 per 1000 person-years in the lowest quartile of partial thromboplastin time, dropping successively with increasing quartile (Table 2). A Kaplan-Meier plot of the incidence of venous thromboembolism over time is shown in Figure 2. The 13-year cumulative incidences of venous thromboembolism for each increasing quartile of activated partial thromboplastin time were 3.1%, 2.2%, 1.2%, and 1.0%, respectively. The proportional hazards assumption was met (treatment by time interaction p = 0.20).

Table 2.

Relative Risk of Incident Venous Thromboembolism by Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Quartile in the Full Cohort and the Nested Case-Control study

| Full Cohort Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Quartile (HR, 95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Number at Risk | 3,491 | 3,509 | 3,352 | 3,528 |

| Cases (n) | 107 | 76 | 40 | 37 |

| Person-Years Follow-up | 43,193 | 44,199 | 42,452 | 44,675 |

| Incidence per 1000 person-years | 2.5 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

|

| ||||

| Unadjusted | 3.06

(2.11, 4.45) |

2.11

(1.43, 3.13) |

1.15

(0.74, 1.80) |

1.00

(Reference) |

| Model 1* | 2.80

(1.92, 4.08) |

2.01

(1.36, 3.00) |

1.15

(0.74, 1.80) |

1.00

(Reference) |

| Model 2† | 1.80

(1.20, 2.71) |

1.62

(1.08, 2.42) |

1.02

(0.65, 1.60) |

1.00

(Reference) |

|

| ||||

| Nested Case-Control Study Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Quartile (OR, 95% CI) | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|

|

||||

| Cases (n) | 107 | 75 | 40 | 36 |

| Controls (n) | 141 | 148 | 145 | 155 |

|

| ||||

| Unadjusted | 3.27

(2.10, 5.08) |

2.18

(1.38, 3.45) |

1.19

(0.72, 1.97) |

1.00

(Reference) |

| Model 1* | 3.15

(2.00, 4.96) |

2.15

(1.35, 3.42) |

1.13

(0.68, 1.90) |

1.00

(Reference) |

| Model 1* + Factor V Leiden | 3.05

(1.90, 4.88) |

2.27

(1.40, 3.69) |

1.15

(0.67, 1.96) |

1.00

(Reference) |

| Model 1 + prothrombin 20210A | 3.09

(1.95, 4.91) |

2.27

(1.42, 3.65) |

1.09

(0.64, 1.85) |

1.00

(Reference) |

| Model 1* + ABO genotype | 2.99

(1.86, 4.79) |

2.16

(1.34, 3.50) |

1.10

(0.66, 1.88) |

1.00

(Reference) |

| Model 1* + Protein C | 3.19

(2.01, 5.06) |

2.18

(1.37, 3.48) |

1.15

(0.68, 1.92) |

1.00

(Reference) |

| Model 1* + D-dimer | 3.52

(2.12, 5.85) |

2.41

(1.43, 4.05) |

1.27

(0.72, 2.24) |

1.00

(Reference) |

| Model 2‡ | 2.39

(1.35, 4.21) |

1.89

(1.10, 3.24) |

1.13

(0.64, 2.01) |

1.00

(Reference) |

Model 1 adjusted for age, gender, race, field center, and body-mass index

adjusted for factors in Model 1 + fibrinogen, factor VIIIc, and von Willebrand factor

adjusted for factors in Model 1 + fibrinogen, factor VIIIc, factor IX, factor XI, and von Willebrand factor

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curve of Cumulative Incidence of Venous Thromboembolism by Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Quartile (Full Cohort).

Activated partial thromboplastin time: Quartile 1: 21.1s – 27.0s; Quartile 2: 27.1s – 28.7s; Quartile 3: 28.8s – 30.6s; Quartile 4: 30.7s – 35.8s

In the full cohort there was an increased risk of venous thromboembolism in the lower two quartiles of activated partial thromboplastin time. Compared to the top quartile, participants in the first quartile had the highest unadjusted hazard ratio, 3.06 (Table 2). There was slight attenuation of the risk with adjustment for age, gender, race, field center, and body-mass index (Model 1). Addition of fibrinogen, factor VIIIc and von Willebrand factor to this model decreased the hazard ratio to 1.80 (Table 2).

The association of activated partial thromboplastin time with venous thromboembolism was similar in the nested case-control group. Addition of coagulation factors VIIIc, IX, XI, fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor to Model 1 lowered the odds ratio for activated partial thromboplastin time in the first and second quartiles, but there remained about a 2-fold increased risk of thrombosis (Table 2). Adjustment for factor V Leiden, prothrombin 20210A, or protein C individually had minimal impact on this association, with ABO genotype and D-dimer had more influence; odds ratios for the first versus fourth quartile decreased from 3.15 to 2.99 adjusting for ABO genotype, and increased to 3.52 adjusting for D-dimer. Odds ratios were similar accounting for all the hemostatic factors simultaneously (data not shown).

In stratified logistic regression models in the nested case-control group, associations of lower activated partial thromboplastin times with thrombosis were somewhat stronger for blacks, men, participants with idiopathic thrombosis, and for pulmonary embolus (Table 3).

Table 3.

Venous Thromboembolism by Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Quartile in Selected Groups (Case-Control Study)*

| Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Quartile OR (95% CI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Stratification | Number of Cases | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Race | White | 177 | 2.06

(1.04, 4.09) |

1.52

(0.79, 2.93) |

1.06

(0.54, 2.10) |

1.00

(Ref.) |

| Non-White | 81 | 3.22

(1.18, 8.81) |

3.00

(1.16, 7.74) |

1.19

(0.41, 3.48) |

1.00

(Ref.) |

|

| Gender | Male | 124 | 3.27

(1.46, 7.33) |

2.54

(1.19, 5.40) |

0.75

(0.32, 1.75) |

1.00

(Ref.) |

| Female | 134 | 1.99

(0.87, 4.55) |

1.56

(0.70, 3.48) |

1.54

(0.68, 3.49) |

1.00

(Ref.) |

|

| Event Type | Idiopathic | 109 | 5.53

(1.97, 15.50) |

4.44

(1.62, 12.20) |

2.31

(0.78, 6.78) |

1.00

(Ref.) |

| Secondary | 149 | 1.74

(0.88, 3.42) |

1.37

(0.72, 2.57) |

0.88

(0.46, 1.71) |

1.00

(Ref.) |

|

| Deep Venous Thrombosis | 178 | 1.83

(0.97, 3.43) |

1.51

(0.83, 2.74) |

0.93

(0.49, 1.77) |

1.00

(Ref.) |

|

| Pulmonary Embolus ± Deep Venous Thrombosis | 80 | 3.93

(1.35, 11.47) |

3.14

(1.10, 9.01) |

2.01

(0.66, 6.07) |

1.00

(Ref.) |

|

Adjusted for age, gender, race, field center, body mass index, fibrinogen, factor VIIIc, factor IXc, factor XIc, and von Willebrand factor

Assessing combinations of risk factors in the nested case-control group, adjusting for age sex and race, activated partial thromboplastin times below the median were supra-additive with obesity, D-dimer above the median (≥0.35 ug/mL), and factor V Leiden (Table 4). The percentage of excess risk above that expected from an additive model of two risk factors was 55% for obesity, 60% for D-dimer above the median, and 63% for factor V Leiden (all p ≤0.01). Compared to the reference group of participants with activated partial thromboplastin times above the median and not obese, those with both risk factors had a 4.7-fold increased risk. This odds ratio was 12.6 for factor V Leiden and 4.9 for higher D-dimer with lower activated partial thromboplastin times.

Table 4.

Age-, Sex-, and Race-Adjusted Odds Ratios and Relative Excess Risk Proportion for Venous Thromboembolism for Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Below the Median and other Venous Thromboembolism Risk Factors (Nested Case-Control Study)

| Variable | Activate Partial Thromboplastin Time (s) | Cases

(n) |

Controls

(n) |

OR (95% CI) | Relative Excess Risk Proportion | p–value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body-Mass Index (kg/m2) | ||||||

| <30.0 | ≥28.8 | 45 | 207 | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| <30.0 | <28.8 | 104 | 208 | 2.37 (1.59, 3.55) | 55% | 0.004 |

| ≥30.0 | ≥28.8 | 23 | 82 | 1.33 (0.75, 2.35) | ||

| ≥30.0 | <28.8 | 85 | 91 | 4.74 (3.03, 7.44) | ||

| Factor VIIIc (%) | ||||||

| <151 | ≥28.8 | 54 | 251 | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| <151 | <28.8 | 97 | 179 | 2.61 (1.77, 3.85) | 14% | 0.61 |

| ≥151 | ≥28.8 | 14 | 38 | 1.83 (0.91, 3.65) | ||

| ≥151 | <28.8 | 93 | 121 | 3.83 (2.54, 5.76) | ||

| D-dimer (ug/mL) | ||||||

| <0.35 | ≥28.8 | 27 | 151 | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| <0.35 | <28.8 | 63 | 160 | 2.36 (1.42, 3.92) | 60% | <0.001 |

| ≥0.35 | ≥28.8 | 26 | 134 | 1.21 (0.66, 2.19) | ||

| ≥0.35 | <28.8 | 94 | 125 | 4.91 (2.95, 8.16) | ||

| Blood Group | ||||||

| O | ≥28.8 | 31 | 151 | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| O | <28.8 | 56 | 105 | 2.64 (1.59, 4.39) | 28% | 0.19 |

| non-O | ≥28.8 | 33 | 125 | 1.27 (0.73, 2.19) | ||

| non-O | <28.8 | 129 | 179 | 3.67 (2.33, 5.76) | ||

| Factor V Leiden | ||||||

| No | ≥28.8 | 59 | 270 | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| No | <28.8 | 158 | 277 | 2.75 (1.94, 3.90) | 63% | 0.008 |

| Yes | ≥28.8 | 5 | 7 | 3.59 (1.09, 11.9) | ||

| Yes | <28.8 | 25 | 10 | 12.59 (5.66, 28.0) | ||

| Prothrombin 20210A | ||||||

| No | ≥28.8 | 63 | 277 | 1.00 (Reference) | ||

| No | <28.8 | 179 | 279 | 2.94 (2.10, 4.11) | <0% | NS |

| Yes | ≥28.8 | 2 | 2 | 3.71 (0.50, 27.3) | ||

| Yes | <28.8 | 4 | 9 | 2.12 (0.62, 7.17) |

p-value for additive interaction

Comment

In this large cohort with 13.1 years of follow-up, baseline activated partial thromboplastin times below the median were associated with increased risk of future venous thromboembolism after adjustment for demographic factors and relevant hemostatic factors. This association was larger for idiopathic than secondary events. Activated partial thromboplastin times below the median were supra-additive with obesity, D-dimer and particularly factor V Leiden to increase thrombosis risk.

Activated partial thromboplastin times were related to age, gender, race and coagulation factor levels measured by this test. Whether this parallels similar differences in factor VIII levels seen with age, gender, and race or other coagulation factors is unknown17. There were no associations between activated partial thromboplastin times and D-dimer, factor V Leiden, or the prothrombin mutation.

Prior studies of the relationship between activated partial thromboplastin times and thrombosis included acutely ill patients, were retrospective or evaluated thrombosis recurrence risk2-4. In 2001, Aboud hypothesized that shorter partial thromboplastin times reflect in-vivo activation of the coagulation system and are a marker for thrombosis in the acute hospital setting2. In 2004 Tripodi reported in a retrospective case-control study that an activated partial thromboplastin time ratio (individual's divided by pooled plasma partial thromboplastin time) ≤5% measured after thrombotic events was associated with a 2.4-fold increased risk3. Consistent with our results, adjustment for factor VIII, ABO blood group, and inherited thrombophilias (antithrombin, protein C, protein S, factor V Leiden and prothrombin 20210A) decreased but did not eliminate the association of lower activated partial thromboplastin times with thrombosis3. Our study extends these findings by defining a much larger number of people having a similar relative risk (partial thromboplastin times below the median vs. the lowest 5%). Recently, Hron and colleagues reported that an activated partial thromboplastin time ratio ≥0.95 was associated with a 42% lower risk of recurrent venous thrombosis after completing anticoagulation after adjustment for age, sex, factor V Leiden, and prothrombin 20210A4. Our data extend the possible utility of the activated partial thromboplastin time as a marker for venous thromboembolism risk before the event.

Our finding that a single determination of the activated partial thromboplastin time was associated with increased long-term risk of venous thromboembolism suggests that this test reflects biochemical changes associated with thrombosis pathophysiology. Larger associations of lower activated partial thromboplastin times with idiopathic than secondary thrombosis suggest genetic factors. Although factor VIIIc is a key determinant of activated partial thromboplastin times1, adjustment for factor VIIIc and other factors in the intrinsic and common coagulation pathways reduced but did not eliminate the observed associations. The activated partial thromboplastin time, a functional assay, may reflect complex interactions of coagulation system proteins not captured by individual factor assays2, 18 There is limited information on combined effects of coagulation factors in the intrinsic and common coagulation cascades on thrombosis risk and more study is needed19.

If our findings are confirmed, observed interactions between lower activated partial thromboplastin times and common thrombosis risk factors such as obesity, D-dimer and factor V Leiden suggest potential clinical use for this test in thrombosis risk assessment. Although obesity is associated with thrombosis risk20, higher factor VIII21 and lower activated partial thromboplastin times, the supra-additive association between obesity and lower activated partial thromboplastin times suggests alternate mechanisms than increased factor levels leading to higher thrombosis risk. The interactions seen between lower activated partial thromboplastin times and D-dimer or factor V Leiden have not been reported before and require further study.

Limitations and strengths of this study need mentioning. ARIC is a study of cardiovascular disease and some thrombosis risk factors (such as family history) were not assessed. The fact that participants were not selected for being at increased risk for venous thrombosis was both a strength and a weakness. Although the study was large and had long follow-up, venous thromboembolism was relatively rare and uncommon risk factors such as prothrombin 20210A could not be extensively studied. Symptomatic deep venous thrombosis may have been missed if it was treated as an outpatient though this would have been rare during the time period of this study. Fatal pulmonary embolism may have been missed, but the impact of this on our findings is likely small. Some factors (such as factor VIII) were measured using activity-based assays while others (such as factors IX, XI) were measured using antigenic assays; associations may vary depending on the assay used. Further we did not have data on all coagulation factors affecting activated partial thromboplastin times. While the reliability coefficient of this assay was high over several weeks, our findings cannot be generalized to acutely ill patients, where variability might be larger7, 14. Any impact of misclassification of activated partial thromboplastin times in this study is likely small since 50% of participants were classified as high risk for thrombosis with this test. Whereas the precise values of the activated partial thromboplastin time associated with thrombosis risk in this study may not be applicable to different laboratories and with different reagents, activated partial thromboplastin times below the median for a laboratory could easily be determined.

In summary, we report that lower activated partial thromboplastin times were associated with a 2-fold increased risk of venous thromboembolism during 13 years of follow-up with a 5.5-fold increased risk of idiopathic events. The association of lower activated partial thromboplastin times with thrombosis was independent of coagulation factors that influence this test. Synergism with other common thrombosis risk factors such as obesity, D-dimer and factor V Leiden suggest possible clinical utility for the activated partial thromboplastin time in thrombosis risk assessment. Populations for future study include hospital inpatients or asymptomatic patients from thrombophilic families.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the investigators, staff and participants of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (http://www.cscc.unc.edu/aric). ARIC is supported by contracts N01-HC-55015, N01-HC-55016, N01-HC-55018, N01-HC 55019, N01-HC-55020, N01-HC-55021, N01-HC-55022, with additional support from R01-HL-59367, all from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.White GC., 2nd The partial thromboplastin time: defining an era in coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1(11):2267–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aboud MR, Ma DD. Increased incidence of venous thrombosis in patients with shortened activated partial thromboplastin times and low ratios for activated protein C resistance. Clinical & Laboratory Haematology. 2001;23(6):411–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2257.2001.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tripodi A, Chantarangkul V, Martinelli I, Bucciarelli P, Mannucci PM. A shortened activated partial thromboplastin time is associated with the risk of venous thromboembolism. Blood. 2004;104(12):3631–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hron G, Eichinger S, Weltermann A, Quehenberger P, Halbmayer WM, Kyrle PA. Prediction of recurrent venous thromboembolism by the activated partial thromboplastin time. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(4):752–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svensson PJ, Dahlback B. Resistance to activated protein C as a basis for venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(8):517–522. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402243300801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bank I, Libourel EJ, Middeldorp S, et al. Elevated levels of FVIII:C within families are associated with an increased risk for venous and arterial thrombosis. Journal of Thrombosis & Haemostasis. 2005;3(1):79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Begbie M, Notley C, Tinlin S, Sawyer L, Lillicrap D. The Factor VIII acute phase response requires the participation of NFkappaB and C/EBP. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84(2):216–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makris M, Colvin B, Gupta V, Shields ML, Smith MP. Venous thrombosis following the use of intermediate purity FVIII concentrate to treat patients with von Willebrand's disease. [see comment] Thrombosis & Haemostasis. 2002;88(3):387–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cushman M, Tsai AW, White RH, et al. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in two cohorts: the Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology. American Journal of Medicine. 2004;117(1):19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried LP, Borhani NO, Enright P, et al. The Cardiovascular Health Study: design and rationale. Ann Epidemiol. 1991;1(3):263–76. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(91)90005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai AW, Cushman M, Rosamond WD, et al. Coagulation factors, inflammation markers, and venous thromboembolism: the Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology (LITE). [see comment] American Journal of Medicine. 2002;113(8):636–42. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Folsom AR, Wu KK, Rosamond WD, Sharrett AR, Chambless LE. Prospective study of hemostatic factors and incidence of coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation. 1997;96(4):1102–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.4.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambless LE, McMahon R, Wu K, Folsom A, Finch A, Shen YL. Short-term intraindividual variability in hemostasis factors. The ARIC Study. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Intraindividual Variability Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1992;2(5):723–33. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(92)90017-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cushman M, Folsom AR, Wang L, et al. Fibrin fragment D-dimer and the risk of future venous thrombosis. [see comment] Blood. 2003;101(4):1243–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilcosky TC, Chambless LE. A comparison of direct adjustment and regression adjustment of epidemiologic measures. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38(10):849–56. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conlan MG, Folsom AR, Finch A, et al. Associations of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor with age, race, sex, and risk factors for atherosclerosis. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. [see comment] Thrombosis & Haemostasis. 1993;70(3):380–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips AN, Smith GD. How independent are “independent” effects? Relative risk estimation when correlated exposures are measured imprecisely. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44(11):1223–31. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tripodi A. Levels of coagulation factors and venous thromboembolism. Haematologica. 2003;88(6):705–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stein PD, Beemath A, Olson RE. Obesity as a risk factor in venous thromboembolism. American Journal of Medicine. 2005;118(9):978–80. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdollahi M, Cushman M, Rosendaal FR. Obesity: risk of venous thrombosis and the interaction with coagulation factor levels and oral contraceptive use. Thrombosis & Haemostasis. 2003;89(3):493–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]