Abstract

The preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus (POA/AH) is characterized by sexually dimorphic features in a number of vertebrates and is a key region of the forebrain for regulating physiological responses and sexual behaviors. Using live-cell, fluorescent video microscopy with organotypic brain slices the current study examined sex differences in the movement characteristics of neurons expressing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) driven by the Thy-1 promoter. Cells in slices from embryonic day 14 (E14), but not E13 mice displayed significant sex differences in their basal neuronal movement characteristics. Exposure to 10nM estradiol-17β (E2), but not 100nM dihydrotestosterone, significantly altered cell movement characteristics within minutes of exposure in a location specific manner. E2 treatment decreased the rate of motion of cells located in the dorsal POA/AH, but increased the frequency of movement in cells located more ventrally. These effects were consistent across age and sex. To further determine whether early developing sex differences in the POA/AH depend upon gonadal steroids, we examined cell positions in mice with a disruption of the steroidogenic factor-1 gene in which gonads do not form. An early born cohort of cells was labeled with the mitotic indicator bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) on E11. More cells were found in the POA/AH of females than males on the day of birth (P0) regardless of gonadal status. These results support the hypothesis that estrogen partially contributes to brain sexual dimorphism through its influence on cell movements during development. Estrogen's influence may be superimposed upon a pre-existing genetic bias.

Keywords: migration, sex differences, mouse, development, sexual differentiation

Introduction

The preoptic area/anterior hypothalamic region (POA/AH) is characterized by a number of sexually dimorphic features. These sex differences range from increased dendritic spine density in males (Amateau and McCarthy, 2004) to the presence of a nuclear group that is considerably larger in males than in females (Gorski et al., 1978; Jacobson et al., 1980; Orikasa et al., 2007). Many of these differences, particularly in rodents, have been ascribed to the influences of estradiol (E2) during critical periods of development that cause long-term changes in neural characteristics (Tobet and Hanna, 1997). Less is known about the cellular mechanisms through which E2 acts to differentiate these regions during development.

Four major mechanisms have been suggested by which gonadal steroids contribute to brain development and differentiation: neurogenesis, cell death, terminal differentiation and migration (Tobet and Hanna, 1997; Simerly, 2002). A number of studies have focused on cell death (Forger, 2006) and terminal differentiation (De Vries and Panzica, 2006) as major mechanisms. There is increasing evidence that sexually dimorphic brain characteristics may derive, in part, from sex and/or hormone influences on neuronal migration. Initially, sex differences and hormone dependence were found for antigen expression in radial glia within the POA/AH of rats (Tobet and Fox, 1989). As radial glia are important for neuron migration, sex differences in these cells may translate into differences in migration. The first direct demonstration of sex differences in migration within the developing POA/AH came from an examination of migratory characteristics of randomly labeled cells using the carbocyanine dye DiI (Henderson et al., 1999). In an avian model, E2 was also shown to influence cell movements (Williams et al., 1999). Finally, the examination of sex differences in the locations of cells containing estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), and calbindin (Orikasa et al., 2002; Wolfe et al., 2005) have suggested possible consequences of sex differences or hormone influences on cell migration.

To directly investigate the influence of E2 on neuronal movements, the current study utilized a transgenic line of mice that expresses yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) under the control of the Thy-1 promoter (Feng et al., 2000) and a brain slice protocol that provides for live video microscopy and in vitro manipulation of hormone exposure (Tobet et al., 2003). As the results showed sex differences in cell movements in the absence of gonadal steroids, one additional experiment asked whether some early aspects of sexual differentiation in the POA/AH might be independent of sex steroids. The mitotic indicator bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) was administered on E11 and brains were examined on postnatal day 0 (P0). Brains from E11 BrdU injected wild-type mice were compared to those in which steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1) was disrupted and in which gonads do not form (Luo et al., 1994, 1995). Finally, to begin determining the phenotype of YFP+ neurons within the developing POA/AH, the co-expression of YFP and ERα, nNOS, and calbindin was examined.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Mice used for slice preparations were housed in the Painter Building of Laboratory Animal Resources at Colorado State University and maintained in plastic cages with aspen bedding (autoclaved sanichips, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI, USA) and environmental enrichments on a 14/10 h light/dark cycle with free access to food (#8640, Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI, USA) and tap water. Female mice were housed with males overnight, with the following day considered to be embryonic day 0 (E0) if vaginal plugs were found.

Transgenic mice expressing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) under the control of the Thy-1 promoter (Thy-1 YFP) were used for embryonic experiments (Feng et al., 2000). This strain was selected because fluorescent protein expression at the developmental ages selected is found reliably in hypothalamic regions of interest (in addition to other sites; Tobet et al., 2003). At the ages examined, YFP expression in the preoptic area/ anterior hypothalamus (POA/AH) was found reliably in two distinct cell groups. Heterozygous male founder mice on a C57BL/6J background were obtained from Jackson Laboratories and crossed with C57BL/6J mice over several generations.

Mice used for BrdU experiments were bred from heterozygous (+/-) SF-1 mice maintained in the Shriver Animal Breeding Facility at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Adults backcrossed to C57BL/6J mice were obtained originally from Dr. Keith Parker (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center). Heterozygous mice (+/-) were bred to generate homozygous wild type (+/+), heterozygous (+/-) and SF-1 knockout (-/-) embryos. Genotyping was conducted as described previously (Luo et al., 1995). Mice were maintained in plastic cages with bedding (Bed O' Cobs, Andersons Agriservices Champaign, Illinois) in a 14/10-light/dark cycle (lights on 07:00) with food (Isopro RMH 3000 Irradiated #25 Purina Mills International, Brentwood, MO) and tap water provided ad libitum. Gestational ages were determined by counting the day sperm plugs were found as day 0 (E0). Where indicated, BrdU (25mg/kg in 0.05 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4)) was administered intraperitoneally to pregnant dams at 1000h on embryonic day 11 (E11). For BrdU detection, mice were perfused on postnatal day 0 (P0) with 2% acrolein (Aldrich Chemical Co., Milwaukee, WI) in 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB: pH 7.4) by using a hand-held syringe with 27 gauge needles under constant observation using a dissecting scope. Animals used for immunocytochemistry other than BrdU were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M PB. Heads and brains were postfixed in the perfusion fixative overnight and then placed in 0.1M PB prior to sectioning in the coronal plane. Animal care was in accordance with the appropriate institutional guidelines.

In Vitro Slice Preparation and Video Microscopy

In vitro slice preparation was similar to that previously reported (Tobet et al., 2003). Timed pregnant animals were used for slice generation on embryonic day 13 or 14 (E13 or E14). Pregnant dams were deeply anesthetized using ketamine/xylazine (80 mg/kg and 8 mg/kg, respectively), and embryos were removed individually by Cesarean section and crown-rump length measurements were taken to verify gestational age (approximately 10mm at E13 and 12mm at E14). Embryos were decapitated and the heads were placed in ice-cold Krebs' solution (NaCl 12.6 mM; KCL 0.25 mM; CaCl2 0.25 mM; MgCl2 0.12 mM; NaH2PO4 0.12 mM). Brains were dissected free of skull, leaving maxilla and pituitary attached, and then immersed in 8% agarose (type VII-A; Sigma; liquid at 39°C) and placed at 4°C to allow the agarose to gel. Brains were sectioned at 250 μm in cold Krebs' solution on a vibrating microtome (VT1000S, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany), and slices were collected in cold sterile-filtered Krebs' solution with 0.01 M HEPES, 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, and 0.1 mg/ml gentamycin.

The POA/AH extends over approximately 500μm at the ages used. To obtain POA/AH slices the first two 250μm sections after the opening of the third ventricle were utilized. Each slice was identified by embryo number to track sex for subsequent video analyses. Both sex and YFP expression were determined by PCR for the Sry gene and YFP transgene, respectively, from tissue collected at the time of dissection. Primers were combined for a multiplex PCR protocol that uses 35 repeats of 94°C for 30 seconds, 60°C for 1 minute and 72°C for 1 minute. The primer sequences used were: YFP (5′-3′) forward, AAG TTC ATC TGC ACC ACC G and reverse, TCC TTG AAG AAG ATG GTG CG for a 173 bp product; and Sry (5′-3′) forward, AGG CGC CCC ATG AAT GCA TT and reverse, TCC GAT GAG GCT GAT ATT TAT AG for a 200 bp product.

After all embryos from a litter were cut, Krebs' solution was replaced for all slices with serum-free Neurobasal medium without phenol red or other potentially estrogenic compounds (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 0.1 mM B-27 (Invitrogen), glutamate, penicillin, streptomycin, L-glutamine, and glucose (collectively, incubation media) and warmed to 35°C. Slices were then placed in an incubator maintained at 35°C with high humidity for 35 minutes. Slices intended for use in video microscopy were placed on glass-bottomed culture dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA, USA) that were coated in poly-L-lysine and collagen (PureCol, Inamed, Fremont, CA, USA). Excess media was siphoned away from slices to facilitate adhesion. After one hour in an incubator at 35°C, slices were overlaid with 23 μl of a solution containing 1 ml PureCol, 125 μl 10X minimum essential medium (Sigma), 23 μl penicillin/streptomycin (10,000 U/ml and 10 mg/ml, respectively; Sigma), and 33 μl 1 M sodium bicarbonate. Dishes were then returned to the incubator for 1.5 hours to allow the overlay solution to gel. Finally, 1 ml of incubation media was added to each dish, which were then returned to the incubator and maintained at 35°C for 1-3 days until used for video microscopy.

Slices were observed using time-lapse video microscopy. For these experiments two microscope/camera workstations were used. The first was a Nikon TE200 inverted microscope equipped with a 20X Plan-Apo objective, Spot SE-6 interline transfer camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI, USA), and LUDL shutter system (Ludl Electronic Products, Hawthorne, NY, USA). This microscope is also fitted with a heated stage (PDMI-2, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA) set to maintain a dish media temperature of 36 °C with a continuous feed of 5% CO2 and continuously infused with fresh media at a rate of 5 ml/hr. The second system was a Nikon TE2000-U inverted microscope equipped with a 20X Plan-Apo objective, Quantix 57 (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ, USA) frame-shift camera, and UniBlitz (Vincent Associates, Rochester, NY, USA) shutter system. This microscope is fitted with a heated incubation chamber (Solent Scientific, Segensworth, UK) equipped with a continuous feed of 5% CO2. Unlike the first microscope, there is no media circulation on the TE2000-U. Although the two microscope workstations differ in whether they infuse media or not, analyses revealed no difference in cellular behaviors or responses to E2 (data not shown). Data from the two microscope systems was pooled for all data sets. Image acquisition for both microscopes was controlled by MetaMorph (v6.2; Molecular Devices Corporation, Downington, PA, USA) software running on separate Dell GX270 PC's. To create the time-lapse, digital images were recorded every five minutes for 30min blocks of time. To maximize data collection with each slice, three images spaced 5 μm apart in the z plane were collected.

Baseline motion was recorded for each slice for 1.5 hours, during which time a volume of vehicle (100% ethanol) equivalent to that used for subsequent steroid treatments was added to each dish. After baseline data collection, slices were treated with E2 at a final concentration of 10nM for the next 1.5 hours. To achieve this, 5 μl of 10mM E2 in ethanol was added to the dish containing the slice and approximately 5 ml of Neurobasal media (final concentration of 10nM) at the first time point. Since the Nikon TE200 is set up with a continuous feed of fresh media, the actual concentration of E2 in the dish decreased over the course of each 30 min video block. To maintain a relatively stable E2 concentration in the dish 2.5 μl of 10 mM E2 was added at the beginning of each subsequent 30min video block. As the TE2000-U does not circulate additional media, 5μl of 10mM E2 was added initially without further additions. After viewing, each slice was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 15 minutes at room temperature and stored in 0.1M PB until used for immunocytochemistry (ICC).

In a subset of experiments to test the specificity of the observed response to E2, 5α-Dihydrotestosterone (DHT; recrystallized and generously provided by Dr. Tom Fox) was administered to slices as described for E2. In these experiments, an equal volume of DHT (5 μl of 100μM DHT in 100% EtOH; final concentration of 100nM) was administered immediately following baseline, with an additional 2.5μl given every 30 minutes for 1.5hr for slices viewed on the TE200. After DHT administration, E2 was added to the dish for an additional 1.5h, as described above. The analysis was identical to the “E2 alone” experiments with the exception that the movement characteristics were analyzed and compared between three repeated measures as opposed to two. As previously mentioned, data was acquired using both video workstations and no differences were found in comparing the results.

Video Analysis

Image sequences were analyzed initially for the presence of visibly moving YFP+ neurons. Analyses were performed using MetaMorph software on a Dell Precision 450 PC using the z-projection and point tracking functions. Image sequences were first aligned using Image J (NIH image) then calibrated, tracked, and analyzed using MetaMorph. To track a fluorescent cell, the centroid of each cell was tracked throughout the entire time-lapse sequence. Position was recorded for each frame, from which the rate and direction of movement was determined (Tobet et al., 2003). An important distinction is made for two major causes of changes in average speed. Average speed may change due to alterations in either the velocity (the rate of movement only when movement occurs) or likelihood of motion (percentage of frames with movement) for a given cell (Tobet and Schwarting, 2006).

Whole-Mount Immunocytochemistry

Immediately following video acquisition, slices were immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15-20 minutes, after which slices were stored in 0.1M phosphate buffer (PB). After storage at least overnight in 0.1 M PB, slices were washed three times in 0.05 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.5) and incubated in 1% sodium borohydride for 2h at 4°C. Slices were then washed twice in PBS before incubation in PBS containing 5% normal goat serum (NGS), 0.3% Triton X-100, and 3% hydrogen peroxide for 2h with one change for fresh solution. Slices were then placed in different primary antisera (in PBS containing 5% NGS and 0.3% Triton X-100) for at least six days. Two GFP antisera were used: Molecular Probes (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) rabbit anti-GFP used at 1:50,000 for fluorescence and 1:400,000 for brightfield, and Chemicon (Temecula, CA, USA) chicken anti-GFP used at 1:2000 for fluorescence and 1:10,000 for brightfield. YFP is a point-mutation derivative of eGFP (T203Y) and is detected by the same antibodies. Two ERα antisera were used: Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) rabbit anti-ER (MC-20) used at 1:500 for fluorescence and 1:5000 for brightfield, and Upstate Biotechnology (Charlottesville, VA, USA) rabbit anti-ERα (c1355) used at 1:1000 for fluorescence and 1:5000 for brightfield. Two nNOS antisera were used: Zymed Laboratories (San Francisco, CA, USA) rabbit anti-nNOS (n-term) used at 1:500 for fluorescence and 1:2,500 for brightfield, and Immunostar (Hudson, WI, USA) rabbit anti-nNOS (c-term) used at 1:1000 for fluorescence and 1:10,000 for brightfield. Two calbindin antibodies were used: Sigma mouse anti-calbindin used at 1:2000 for fluorescence and 1:40,000 for brightfield, and Chemicon (Temecula, CA, USA) rabbit anti-calbindin used at 1:500 for fluorescence and 1:2500 for brightfield. The anti-BrdU mouse monoclonal antibody was obtained from Becton Dickinson Immunocytochemistry Systems (1:75 dilution). After primary antibody was removed, slices were washed four times in 2h in PBS containing 1% NGS and 0.02% Triton X-100. Next, Slices were incubated overnight in biotinylated secondary antibodies specific for the primary antibodies used. On the next morning, slices were washed four times over 2h in PBS containing 0.02% Triton X-100 before 3h incubation in peroxidase conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) at room temperature. To visualize immunoreactivity for brightfield analyses, slices were washed in PBS and incubated at room temperature in 2 ml 0.025% DAB in PBS for 15 minutes. After 15 minutes, hydrogen peroxide was added to the dish to a final concentration of 1% and reacted for 20 minutes. For immunofluorescence, slices were washed for 2h after incubation with the appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibody and then mounted on slides and coverslipped with aqueous mounting media.

Thin-section immunocytochemistry (60μm) was performed on perfusion fixed E14/15 brains for greater resolution. The procedure was similar to that used for the thick sections, but with shorter incubation times (Tobet et al., 2003). Specifically, wash and block times were reduced to one hour, primary antibody incubation was reduced to 3 nights, and secondary antibody incubations were reduced to 2 hours.

Analysis of Immunoreactive BrdU

Immunoreactive BrdU was analyzed using IPLab software (Scanalytics Inc., Fairfax, VA) that created a grid system overlay to map immunoreactivity relative to spatial location (Davis et al., 2004). Images were digitized using a 10X objective and contrast enhanced to demarcate immunoreactive cells clearly above background. The grid was aligned with the 3rd ventricle and extended laterally 480μm in 80μm increments. The grid was aligned ventrally at the base of the brain and extended 640μm dorsally (about the level of the anterior commissure) also in 80μm increments. Following image segmention, the area of immunoreactive elements was measured in each square from one side of each brain. The side with the largest distribution of immunoreactive elements was chosen as the most conservative approach for defining the changing distribution, since it makes the fewest assumptions. The data were analyzed in a 3 way ANOVA of sex × row × column (JMP 4.0 Statistical Package; SAS Institute). Data from the BrdU analysis was based only on sections with a similar angle of sectioning with the midpoint of the anterior commissure aligned with the midpoint of the optic chiasm.

Results

Cell groups visible in the embryonic POA/AH

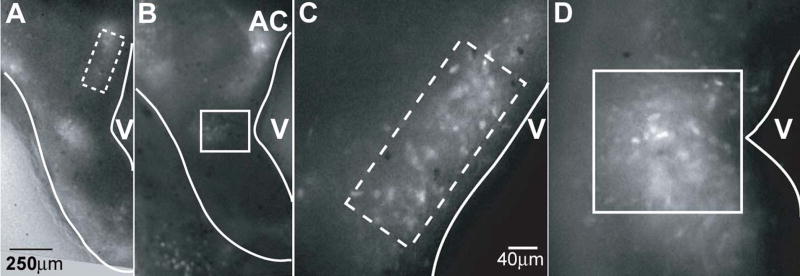

Two distinct groups of fluorescent cells were visible in slices through the POA/AH. In the more rostral slices, ventral to the anterior commissure, a vertical “stripe” of YFP+ cells adjacent to the third ventricle was evident at E13 and 14 (Figure 1a and c, dashed box). This group is referred to as the dorsal cell group. In more caudal slices a second group of cells, located more ventrally and extending laterally from the middle of the third ventricle, was visible in addition to the dorsal group (Figure 1b and d, solid box). This group of cells is referred to as the ventral group.

Figure 1. Fluorescence microscopy reveals two distinct groups of cells expressing YFP in the developing POA/AH.

Panels A and B show low magnification fluorescent photomicrographs of the POA/AH at E13 and E14, respectively. At both ages two distinct groups of YFP+ cells are evident, designated dorsal (dashed box) and ventral (solid box). Panels C and D show higher magnification photomicrographs of the field of view used for video acquisition. AC, anterior commissure; V, third ventricle. The scale bar in A represents 250μm for panels A and B and the scale bar in C represents 40μm for panels C and D.

Basal Movement Characteristics

Similar to previous reports using video microscopy, YFP+ cells in the POA/AH moved with speeds ranging from 12 to 120 μm/hr, with an average movement speed of approximately 20 μm/hr (Figure 2b). YFP+ cells were observed to move in both medial-lateral and dorsal-ventral orientations. Radial fibers (RC2 immunoreactive) were found extending in both orientations, although movements were seen along more orientations than accountable by radial fibers. No differences were detected in the orientation of motion either between sexes or between cell groups (data not shown).

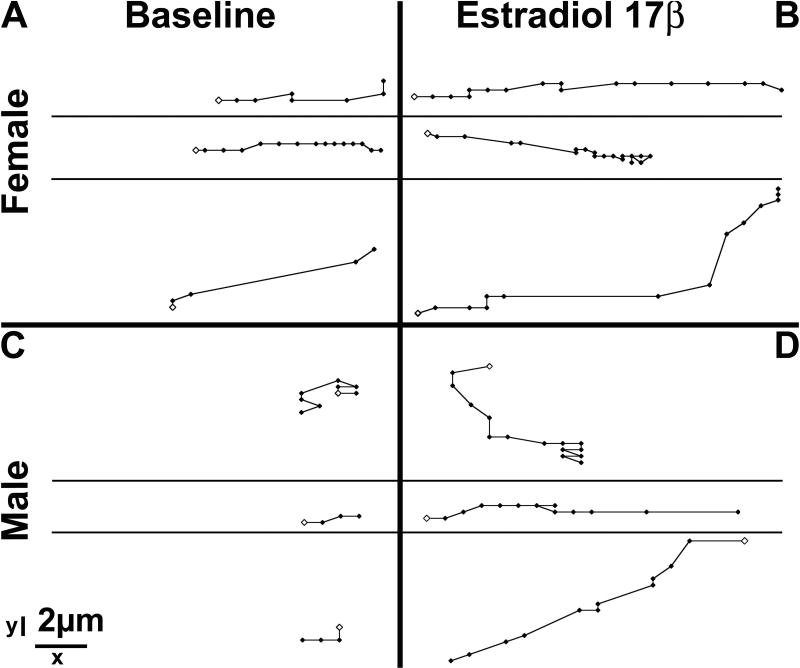

Figure 2. Neuronal movement characteristics differ between cells in slices taken from males and those in slices taken from females at E14 in the ventral cell group.

Representative cell tracking schematics show that YFP+ cells in slices taken from females (panels A and B) move faster (average distance between any two points) and more frequently (average number of points) than YFP+ cells in slices taken from males (panels C and D) in both baseline and 10nM E2 conditions. Each track represents the path taken by a given cell in 1.5h, with each point showing a tracked position of the cell and the open point showing the starting position. Although E2 increased the average speed and probability of movement in both sexes, a sex difference exists in both conditions. Scale bars show dimension in x and y orientations.

In slices taken at E13, no sex differences in basal motion were detected for cells in either cell group. In slices started a day later, at E14, a dramatic difference in neuronal movement characteristics emerged for the ventral cell group. Figure 2 shows tracking schematics for 3 representative cells from each sex. Panels A and C show the paths taken by these cells during baseline video and demonstrate the differences in basal movement characteristics. Panels B and D show the path taken by the same 6 cells during E2 administration. These results are specific to the ventral group.

Quantitatively, YFP+ cells in slices taken from females at E14 move nearly three times as fast as YFP+ cells in slices taken from males at E14 under baseline conditions (11.2 μm/hr vs. 3.4 μm/hr; Figure 3A; F(1,22)=11.8, p<0.01). In addition, YFP+ cells in slices taken from females at E14 moved an average of three times more frequently than YFP+ cells in slices taken from males at E14 during baseline video (33% of frames vs. 9.5%; Figure 3B; F(1,22)=9.75, p<0.01).

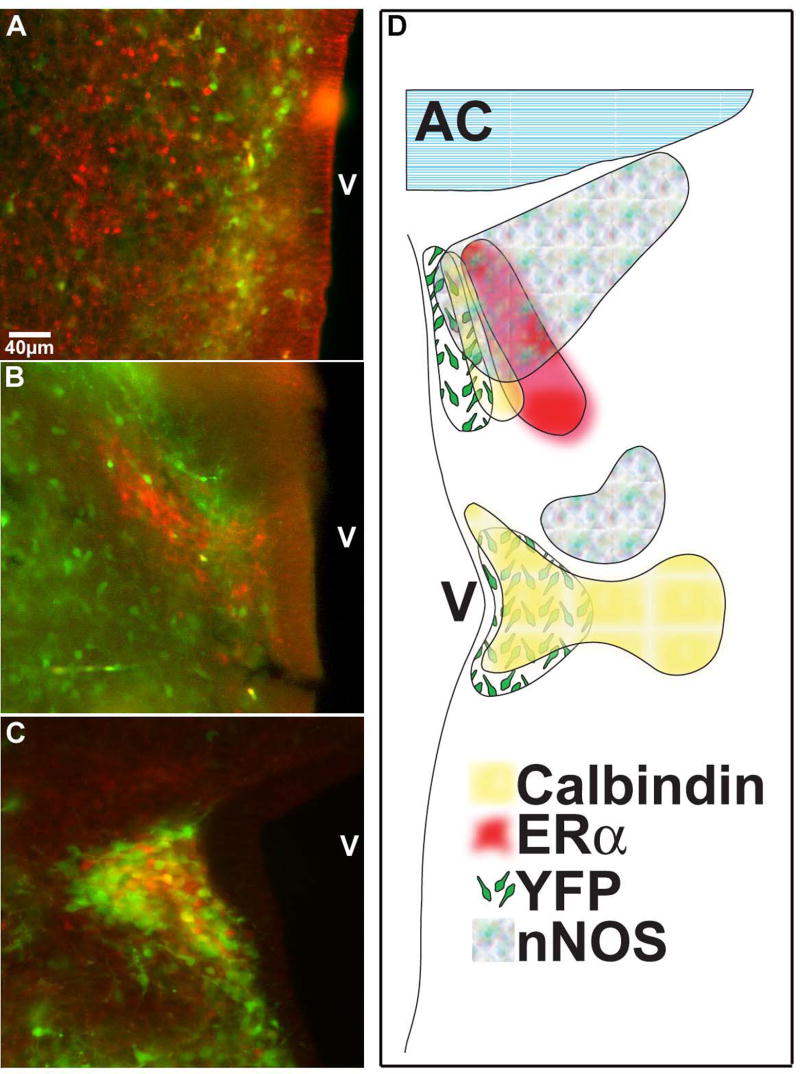

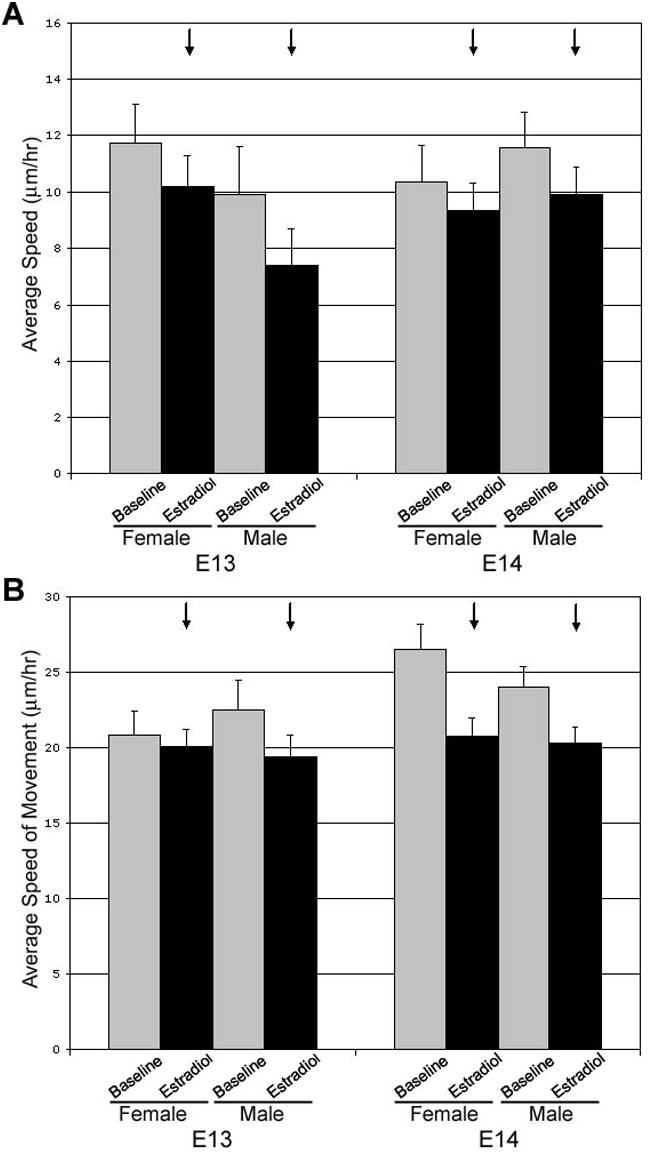

Figure 3. Administration of 10nM Estradiol-17β, but not 100nM DHT, caused an increase in the average speed of YFP+ cells in the ventral cell group independent of age or sex.

E2 administration significantly increased the average speed of YFP+ cells in slices taken from either males or females at E13 or E14 (black arrows in A; p<0.05). A sex difference in the basal average speed and frequency of movement emerges at E14 with YFP+ cells in slices taken form females moving significantly faster and more often (* over bracket in panel B; p<0.05) than YFP+ cells in slices taken from males. Panel C shows that YFP+ cells in slices taken from females at E14 respond to E2 but not DHT with increased speed and frequency of movement (** over bracket; p<0.01). Values are mean ± SEM for female YFP+ cells (n=13) and male YFP+ cells (n=11).

Effect of Estradiol-17β on Cell Movements

Administration of 10nM estradiol-17β altered cell movement characteristics in both cell groups at both E13 and E14, although the specific effect was dependent on location (see supplemental video). In the ventral cell group, the overall effect of estradiol was to increase the average speed of YFP+ cells regardless of sex or age (Figure 3A and B; F(1,44)=5.21, p<0.05). By contrast, the administration of 100nM 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT) did not elicit a response from YFP+ cells in the ventral group. There was no difference between movement characteristics during baseline and in the presence of DHT with regard to either the average speed (F(1,9)=1.26, p=0.29) or percent of frames with movement (F(1,9)=2.93, p=0.12). Following DHT administration, the addition of E2 was still able to elicit an increase in both average speed (Figure 3C; F(1,9)=13.2, p<0.01) and percent of frames with movement (Figure 3C; F(1,9)=10.4, p<0.01) similar to the results seen for E2 alone. In the dorsal group, the overall effect of estradiol was to decrease the average speed of cells regardless of sex or age (Figure 4A; F(1,69)=4.23, p<0.05). Further analysis revealed that this decrease in average speed was due to a decrease in the rate of motion rather than the probability of motion (Figure 4B; F(1,63)=11.6, p<0.01).

Figure 4. Administration of 10nM Estradiol-17β decreases the average speed and movement speed of YFP+ cells in the dorsal cell group independent of age or sex.

E2 administration (A) significantly decreases the average speed (black arrows; p<0.05) of YFP+ cells and (B) also decreases the average speed of movement (black arrows; p<0.01) of YFP+ cells in slices taken from either males or females at E13 or E14. Values are mean±SEM for female YFP+ cells (n=10) and male YFP+ cells n=22.

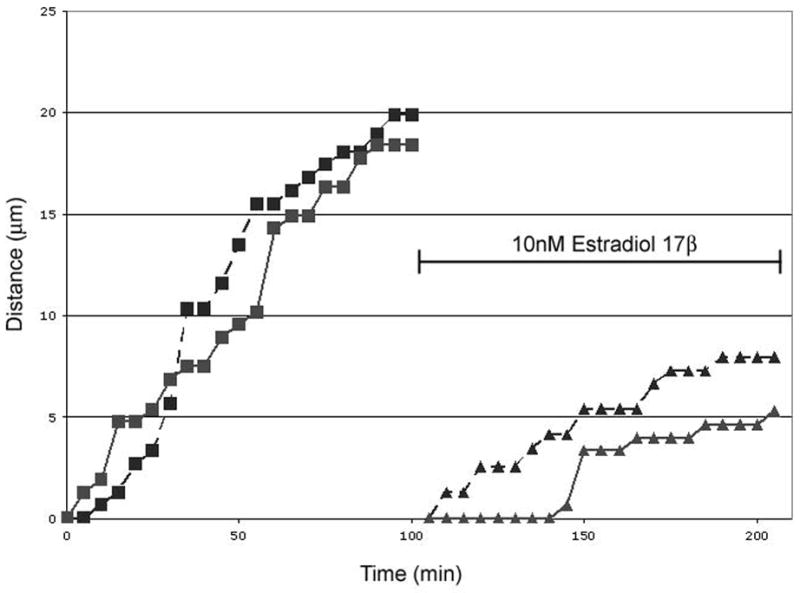

In both cell groups, the observed effect of E2 was relatively rapid. Bath administration of E2 resulted in the region-specific effects within the first 30 minutes of recording (see supplemental video). Graphic representations of cell speed demonstrate that the decrease in speed in the dorsal group is similarly rapid (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The effect of estradiol-17β on YFP+ cells was relatively rapid in the dorsal group.

Schematic, cumulative distance graphs of two representative cells in the dorsal group, in which E2 decreases the average speed, from a slice taken from a female at E14 demonstrate the speed of action of E2. The same two cells are shown before and after E2 administration. The slope of each line represents the average speed of that particular cell; level portions of the graph show that the cell did not move between those frames. Each line represents 1.5h of video.

Hormone independence of cell characteristics in the POA/AH

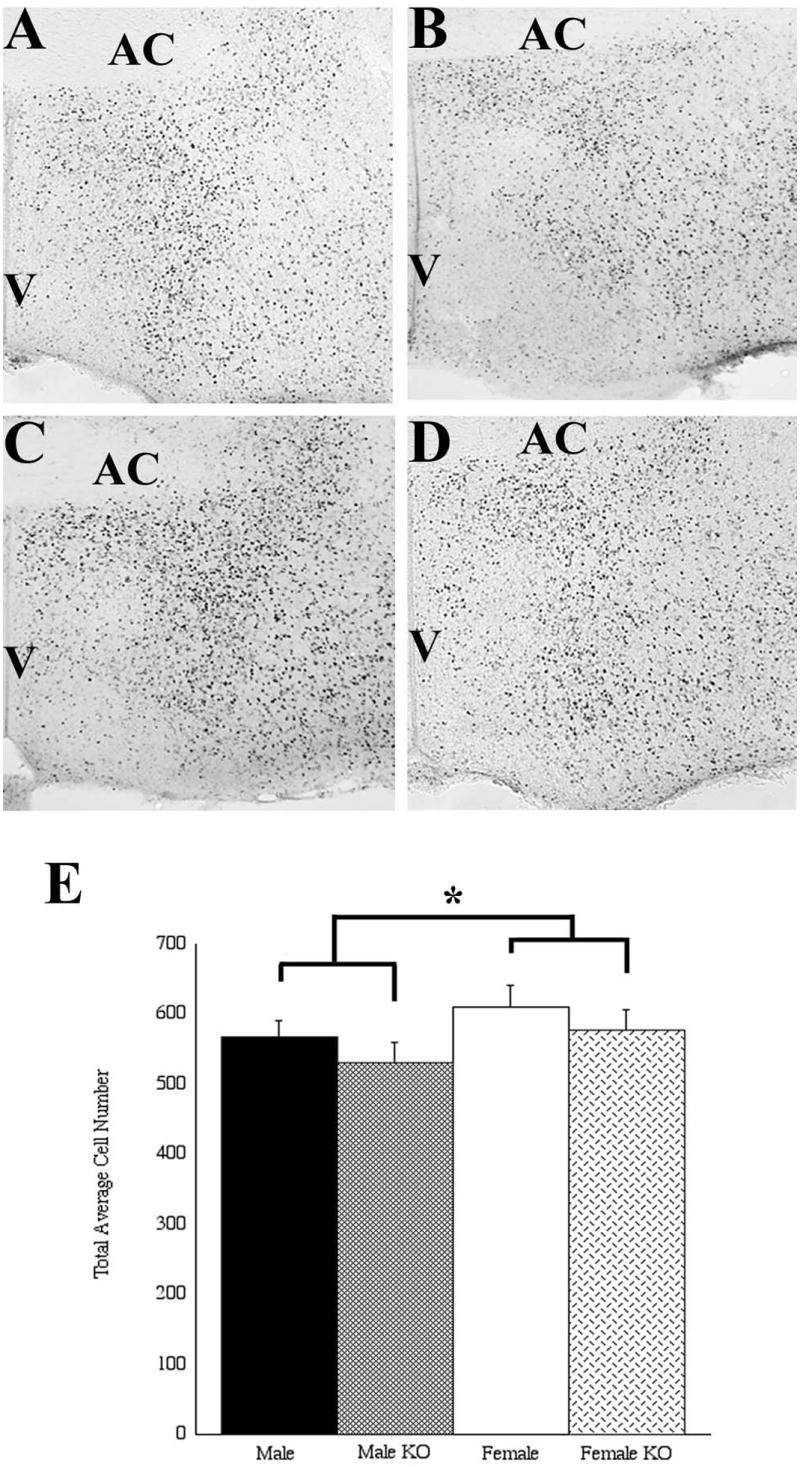

To determine if some characteristics of cells in the POA/AH exist independent of gonadal steroid exposure, BrdU was administered at E11 to pregnant females of the SF-1 KO line and the POA/AH was analyzed at P0. Results were compared between sex and genotype (SF-1 -/- KO and SF-1 +/+ WT littermates). There was a significant effect of sex for cells born on E11 with females having more BrdU positive cells than males (F(1,50)=6.95, p<0.01), but no effect due to genotype (F(1,50)=2.55, p>0.1; Figure 6). SF-1 knockout females still had more BrdU positive cells than SF-1 knockout males even though their gonadal status was identical (i.e., no gonads). When analyzed by position, there were no statistically significant interactions between either sex or genotype and position measured either dorsal to ventral or medial to lateral.

Figure 6. BrdU birthdate labeling in the POA shows a significant effect of sex with no effect of genotype.

Males (A,B) had fewer cells labeled for BrdU than females (C,D) when BrdU was administered at embryonic day 11 and examined at postnatal day 0. Wildtype males (A) had similar numbers of BrdU labeled cells to SF-1 knockout (KO) males (B), and wildtype females (C) had similar numbers of BrdU labeled cells to SF-1 knockout females (D). AC, anterior commisure; V, third ventricle. * p < 0.01.

Cell Phenotypes

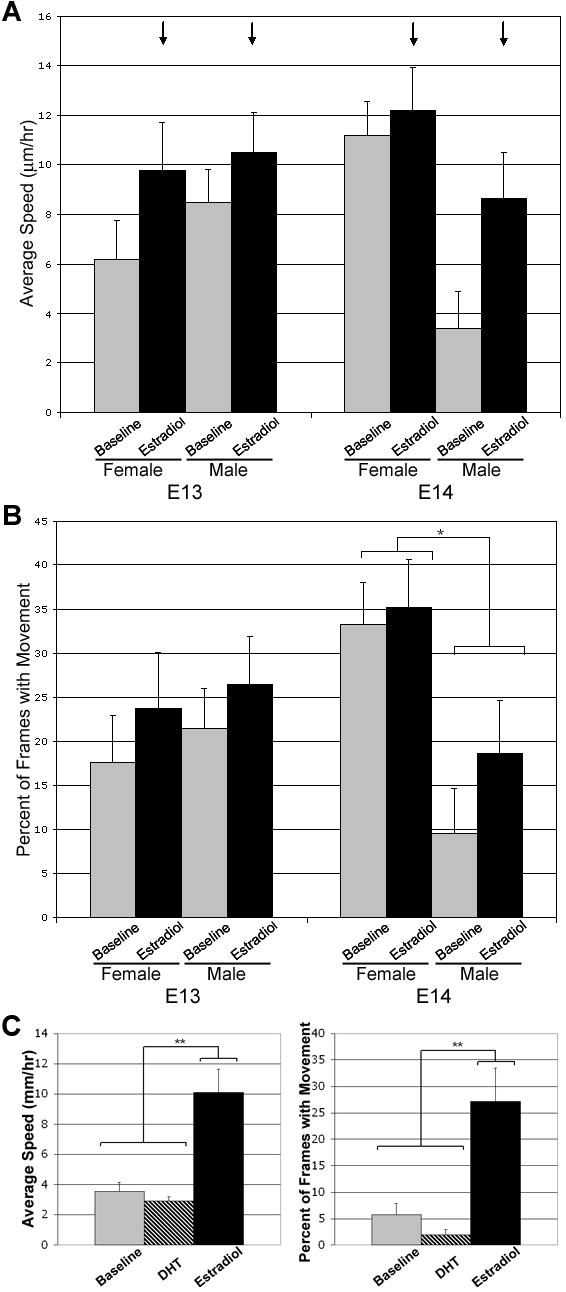

In an effort to better understand the phenotype of the cells observed for movements, dual-label immunocytochemistry was used for YFP and specific cellular markers in immersion fixed 250 μm thick slices after viewing and in 60μm thick sections from aldehyde perfused mice. Expression profiles varied at different ages (e.g. higher expression of YFP at later ages, data not shown), but certain aspects of the region remained similar at each age examined. For example, classic nuclear immunoreactivity for estrogen receptor-α (ERα-ir) was observed adjacent to, but not overlapping, the dorsal cell group starting at E13 (Figure 7A). No co-localization of YFP-ir and ERα-ir was observed at any age analyzed. nNOS-ir was observed lateral to, and partially overlapping, the dorsal cell group at all ages although there was little to no co-localization (Figure 7B). nNOS-ir was also observed lateral to, though not overlapping, the ventral cell group as well, though also with no co-localization (data not shown). In the ventral cell group, YFP-ir and calbindin-ir co-localized in some, but not all, of the YFP+ cells (Figure 7C, non-quantified observation). A graphic representation of the patterns of immunoreactivity seen in the POA/AH is shown in Figure 7D.

Figure 7. Immunocytochemistry reveals the phenotype of the YFP+ cells.

(A) ERα immunoreactive (red) and YFP-immunoreactive (green) cells were both easily detected in the dorsal region, but not in the same cells, as early as E13. (B) nNOS-immunoreactive (red) and YFP-immunoreactive (green) cells were detectable in the caudal dorsal region in an overlapping, though not co-localizing pattern as early as E13. (C) In caudal sections, some but not all YFP+ (green) cells also contained immunoreactive calbindin (red). (D) Graphic representation of the typical distribution of specific expression patterns in the POA/AH. AC=anterior commisure; V=third ventricle.

Discussion

There are several ways to envision the emergence of sex differences in brain structure or function during development. For one, sex differences may emerge hormone-independently as function of genetic mechanisms (Arnold et al., 2004). More common hypotheses focus on the role(s) of gonadal steroid hormones during development (Tobet and Hanna, 1997; Simerly, 2002). Gonadal steroids, however, can be conceptualized in 2 types of roles (Arnold and Breedlove, 1985): organizational (i.e., long lasting) or activational (i.e., short term hormone response). The current study contributes evidence that all three mechanisms may be active in the POA/AH, a location rich in sexually dimorphic characteristics in many species (Tobet and Fox, 1992), including mice (Brown et al., 1999; Mathieson et al., 2000; Wolfe et al., 2005). The current experiments indicate hormone independence for the retention of BrdU immunoreactive cells born on E11, and also hormone dependence for cell movements at E13 and E14. Although cells from slices started at both ages were capable of responding to estradiol (activational hormone influence), only cells in slices started on E14 showed sex differences in cell movements in the absence of hormone treatment. There are two likely sources of ‘programming’ for basal sex differences seen in cells from E14 slices. First, a hormone-independent mechanism similar to one that led to more E11 born BrdU immunoreactive cells in females than males may alter the movement behavior of cells. Secondarily, hormone exposure prior to slices being prepared on E14 (Pointis et al., 1980; vom Saal and Bronson, 1980) may alter the subsequent behavior of cells examined in the absence of gonadal steroids (organizational hormone influence). In every case, the current study suggests that a key focal point for sexual programming of brain structure occurs early in brain development and prior to the commonly consider prenatal surge in testicular hormones (Weisz and Ward, 1980).

Sex differences and hormone influences on cell movements are likely to be restricted in their locations and the nature of effects may differ by region as well as by developmental age. Interestingly, the changes in antigen expression in an early study (Tobet and Fox, 1989) and the sex differences in cell motions in a later study (Henderson et al., 1999) were restricted in location; particularly to caudal regions in the POA close to the boundary with the anterior hypothalamus. In the current experiments sex differences in basal movement characteristics were only found in the ventral cell group, generally found in the more caudal sections. It may well be that similar sex differences exist in other parts of the POA/AH, perhaps even in the dorsal cell group analyzed in the current experiment, but at different times. Further investigation of these phenomena at different time points may help elucidate “critical periods” for migration in other areas. Another regional difference in this study was the nature of the response to estradiol. Cells in both groups responded to estradiol by altering their movement characteristics, but in opposite ways. Cells in the dorsal group responded with decreased movement, while cells in the ventral group responded with increased movement. Similarly for cell death mechanisms, hormone influences in AVPV may increase cell death while the same hormone influence may decrease cell death in the POA and BST (Forger, 2006). These differences highlight the importance of location in determining cellular behaviors.

In the current experiments, estradiol affected the movement characteristics of YFP+ cells in both of the regions scrutinized over a relatively rapid time course. Regardless of the particular group, the effects of estradiol administration were evident within the first 30 minutes. Further quantification of the exact timing is difficult due to the variability of individual cells, the length of time between image acquisition, and the possible delay due to bath administration, which may result in mixing/diffusion differences between slices. There is a growing body of evidence for the existence of fast-acting, membrane associated estrogen receptors that act through second messenger systems (Ronnekleiv and Kelly, 2005; Vasudevan and Pfaff, 2007). This may help to explain why we were unable to detect immunoreactive ERα in the YFP+ cells in this experiment, although the absence of detection speaks only to the sensitivity of our methods and not the absolute absence of the receptor. It has been postulated that as much as three percent of the ERα in a cell may be localized to the membrane, a concentration that is probably below our current detection limits (Razandi et al., 1999). Interestingly, some reports show that estradiol can directly modulate migration characteristics. For example, an increase in directed migration in cancer cell lines following estradiol treatment has been attributed to rapidly altered cytoskeletal dynamics (Azios and Dharmawardhane, 2005; Acconcia et al., 2006). Alternatively, estrogenic effects on motion may be dependent on secondary signaling systems. For example, estradiol has been shown to alter the activity of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). In this experiment immunoreactive nNOS was seen in cells closely apposed to those containing YFP, although not co-localizing with YFP-ir. In addition to being somewhat dependent on estradiol, nitric oxide (NO) has been shown to alter neuronal migration in some species (Haase and Bicker, 2003). In an independent recent study, a sex difference in nNOS immunoreactive cells was found in the POA/AH in the region where cell movements were observed in the current study (Edelman et al., 2007).

Sex differences in migration may exist selectively for cells of specific developmental histories and phenotypes. Previous experiments using mice have found sex differences in the number and location of calbindin positive cells in the POA/AH (Edelman et al., 2007). Calbindin expression, as a biomarker, has been found to be strongly sex-dependent in several species (Bisenius et al., 2006), specifically within the POA/AH. In the current experiment, some co-localization with YFP-ir was found in the ventral cell group, however, calbindin is clearly not expressed in all of these cells. Future studies may be able to determine whether there is linkage between birthdate and migratory characteristics. In the current study, there were more cells found in females than males to be BrdU positive on P0 after an E11 injection in the same POA/AH region where cell motions were evaluated. The sex difference in immunoreactive BrdU cell number was gonadal hormone independent considering that SF-1 knockout animals develop in the absence of gonads (Luo et al., 1994). A previous experiment (Henderson et al., 1999) found no sex difference in the number of cells when BrdU injections were given at E15, suggesting that sex differences can only be detected for cells born at certain times. The administration of BrdU at E11 is a critical time point since it is prior to the formation of the embryonic gonad. This is consistent with sex differences being set up well before the involvement of gonadal steroid hormones.

If sex differences and hormone influences act on cell positions, then there should be an increasing number of sexual dimorphisms found where the positions of cells is as much a part of the dimorphism as is the number of cells. Previously, we showed a sex difference in the location of cells expressing either estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) or γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAB) receptor R1 subunit (GABABR1) in the POA/AH of mice at E17 (Wolfe et al., 2005). Although the total number of immunoreactive ERβ or GABABR1 neurons did not differ by sex at E17, the location of each subset did vary by sex. Immunoreactive ERβ cells were located more ventrally and medially in males than in females and immunoreactive GABABR1 neurons were located more ventrally in males than in females. Relative to the current results, the area in which these differences were noted corresponds to the location where estradiol was found to decrease the speed and frequency of movement of YFP+ cells. Although it is not known to what extent the YFP+ cells in this region will ultimately express ERβ, it is interesting to note that the effect of estradiol appears to be consistent in that the cells that are sensitive to this steroid would be located more medially in males in both cases. In rats, a similar sex difference was detected in the location of immunoreactive ERβ neurons in the AVPV (Orikasa et al., 2002). In this case, immunoreactive ERβ neurons were located more laterally in males than in females. Interestingly, this difference was reversed by perinatal orchidectomy of males or estradiol treatment of females, providing further evidence of steroid hormones directly affecting the position of specific neurons.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Kristy McClellan, Brandon Wadas, Kelsey Schneider, Emily Aurand, and Alecia Love for assistance with the mice during the project. We thank Dr. Thomas Fox for providing recrystallized dihydrotestosterone. This research was supported by MH61376 (SAT).

Abbreviations

- AVPV

anteroventral-periventricular nucleus

- BNST

bed nucleus of the stria terminalis

- BrdU

bromodeoxyuridine

- DHT

5α-dihydrotestosterone

- E2

estradiol-17β

- ERβ

estrogen receptor β

- -ir

immunoreactivity

- POA/AH

preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus

- SDN-POA

sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area

- YFP

yellow-fluorescent protein

References

- Acconcia F, Barnes CJ, Kumar R. Estrogen and tamoxifen induce cytoskeletal remodeling and migration in endometrial cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1203–1212. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amateau SK, McCarthy MM. Induction of PGE2 by estradiol mediates developmental masculinization of sex behavior. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:643–650. doi: 10.1038/nn1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold AP, Breedlove SM. Organizational and activational effects of sex steroids on brain and behavior: a reanalysis. Horm Behav. 1985;19:469–498. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(85)90042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold AP, Xu J, Grisham W, Chen X, Kim YH, Itoh Y. Minireview: Sex chromosomes and brain sexual differentiation. Endocrinology. 2004;145:1057–1062. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azios NG, Dharmawardhane SF. Resveratrol and estradiol exert disparate effects on cell migration, cell surface actin structures, and focal adhesion assembly in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2005;7:128–140. doi: 10.1593/neo.04346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisenius ES, Veeramachaneni DN, Sammonds GE, Tobet S. Sex differences and the development of the rabbit brain: effects of vinclozolin. Biol Reprod. 2006;75:469–476. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.052795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AE, Mani S, Tobet SA. The preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus of different strains of mice: sex differences and development. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1999;115:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries GJ, Panzica GC. Sexual differentiation of central vasopressin and vasotocin systems in vertebrates: different mechanisms, similar endpoints. Neuroscience. 2006;138:947–955. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelmann M, Wolfe C, Skordalakes EM, Rissman EF, Tobet S. Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase and Calbindin Delineate Sex Differences in the Developing Hypothalamus and Preoptic Area. Develop Neurobiol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/dneu.20507. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng G, Mellor RH, Bernstein M, Keller-Peck C, Nguyen QT, Wallace M, Nerbonne JM, Lichtman JW, Sanes JR. Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron. 2000;28:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forger NG. Cell death and sexual differentiation of the nervous system. Neuroscience. 2006;138:929–938. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorski RA, Gordon JH, Shryne JE, Southam AM. Evidence for a morphological sex difference within the medial preoptic area of the rat brain. Brain Res. 1978;148:333–346. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90723-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase A, Bicker G. Nitric oxide and cyclic nucleotides are regulators of neuronal migration in an insect embryo. Development. 2003;130:3977–3987. doi: 10.1242/dev.00612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson RG, Brown AE, Tobet SA. Sex differences in cell migration in the preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus of mice. J Neurobiol. 1999;41:252–266. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19991105)41:2<252::aid-neu8>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson CD, Shryne JE, Shapiro F, Gorski RA. Ontogeny of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area. J Comp Neurol. 1980;193:541–548. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Ikeda Y, Parker KL. A cell-specific nuclear receptor is essential for adrenal and gonadal development and sexual differentiation. Cell. 1994;77:481–490. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Ikeda Y, Parker KL. The cell-specific nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor 1 plays multiple roles in reproductive function. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1995;350:279–283. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1995.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson WB, Taylor SW, Marshall M, Neumann PE. Strain and sex differences in the morphology of the medial preoptic nucleus of mice. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428:254–265. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001211)428:2<254::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orikasa C, Kondo Y, Sakuma Y. Transient transcription of the somatostatin gene at the time of estrogen-dependent organization of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the rat preoptic area. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1144–1149. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orikasa C, Kondo Y, Hayashi S, McEwen BS, Sakuma Y. Sexually dimorphic expression of estrogen receptor beta in the anteroventral periventricular nucleus of the rat preoptic area: implication in luteinizing hormone surge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3306–3311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052707299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pointis G, Latreille MT, Cedard L. Gonado-pituitary relationships in the fetal mouse at various times during sexual differentiation. J Endocrinol. 1980;86:483–488. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0860483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razandi M, Pedram A, Greene GL, Levin ER. Cell membrane and nuclear estrogen receptors (ERs) originate from a single transcript: studies of ERalpha and ERbeta expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:307–319. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.2.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Diversity of ovarian steroid signaling in the hypothalamus. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2005;26:65–84. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sickel MJ, McCarthy MM. Calbindin-D28k immunoreactivity is a marker for a subdivision of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area of the rat: developmental profile and gonadal steroid modulation. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:397–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly RB. Wired for reproduction: organization and development of sexually dimorphic circuits in the mammalian forebrain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:507–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobet SA, Fox TO. Sex- and hormone-dependent antigen immunoreactivity in developing rat hypothalamus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:382–386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobet SA, Fox TO. In: Handbook of Behavioral Neurobiology. Vol 11: Sexual Differentiation. Gerall AG, Moltz H, Ward IL, editors. Plenum Press; New York: 1992. pp. 41–69. [Google Scholar]

- Tobet SA, Hanna IK. Ontogeny of sex differences in the mammalian hypothalamus and preoptic area. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1997;17:565–601. doi: 10.1023/A:1022529918810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobet SA, Schwarting GA. Minireview: recent progress in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal migration. Endocrinology. 2006;147:1159–1165. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobet SA, Walker HJ, Seney ML, Yu KW. Viewing cell movements in the developing neuroendocrine brain. Integr Comp Biol. 2003;43:794–801. doi: 10.1093/icb/43.6.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan N, Pfaff DW. Membrane-initiated actions of estrogens in neuroendocrinology: emerging principles. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:1–19. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vom Saal FS, Bronson FH. Sexual characteristics of adult female mice are correlated with their blood testosterone levels during prenatal development. Science. 1980;208:597–599. doi: 10.1126/science.7367881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz J, Ward IL. Plasma testosterone and progesterone titers of pregnant rats, their male and female fetuses, and neonatal offspring. Endocrinonlogy. 1980;106:306–316. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-1-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams S, Leventhal C, Lemmon V, Nedergaard M, Goldman SA. Estrogen promotes the initial migration and inception of NgCAM-dependent calcium-signaling by new neurons of the adult songbird brain. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1999;13:41–55. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1998.0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe CA, Van Doren M, Walker HJ, Seney ML, McClellan KM, Tobet SA. Sex differences in the location of immunochemically defined cell populations in the mouse preoptic area/anterior hypothalamus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2005;157:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.