Abstract

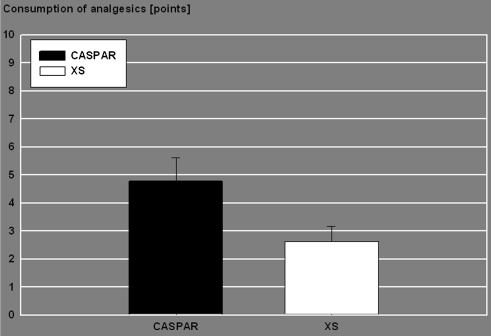

Conventional lumbar microdiscectomy requires subperiosteal dissection of the muscular and tendineous insertions from the midline structures. This prospective, randomized, single center trial aimed to compare a blunt splitting transmuscular approach to the interlaminar window with the subperiosteal microsurgical technique. Two experienced surgeons performed first time lumbar microdiscectomy on 125 patients. The type of approach and retractor used was randomized and both patients and evaluator were blinded to it. In 59 patients a speculum-counter-retractor was inserted through a subperiosteal (SP) route and in 66 patients an expandable tubular retractor was introduced via a transmuscular (TM) approach. In both groups the mean age was 51 years, the male gender prevalent (61%) and the distribution of the operated levels was similar. The outcome measures were VAS for back and leg pain, ODI and the postoperative analgesic consumption was scored by the WHO 3-class protocol. A postsurgical VAS (0–1) was defined as excellent, VAS (2–4) as satisfactory result. In this study the patients scored from 1 to 3 points daily according to the class of drugs taken. Furthermore, a 1/3 point (class 1), 2/3 point (class 2) and 1 point (class 3) was added for each on-demand drug intake. Recovery from radicular pain was excellent (SP 68%, TM 76%) or satisfactory (SP 23%, TM 21%). Recovery from back pain was excellent (SP 58%, TM 59%) or satisfactory (SP 37%, TM 37%). Postoperative mean improvement ODI was: SP 29% and TM 31%. Postoperative mean analgesic intake: SP 4.8 points, TM 2.6 points (P = 0.03). Lumbar microdiscectomy improves pain and ODI irrespective of the type of approach and retractor used. However, the postsurgical analgesic consumption is significantly less if a tubular retractor is inserted via a transmuscular approach.

Keywords: Lumbar microdiscectomy, Microendoscopic technique, Tubular retractor, Transmuscular approach, Subperiosteal approach

Introduction

Lumbar microdiscectomy is a popular procedure for the surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniations [15]. The success rate ranges from 80 to 95% [2].

The conventional subperiosteal approach requires incision of tendinous insertions of the paraspinal muscles and their retraction from the spinous process. The paravertebral muscles are rich in proprioceptors and are injured by local ischemia when retracted. There are reports on the correlation between denervation and retraction-ischemia of the muscles and postoperative pain [9]. It can be assumed that this holds also true at certain extent for the subperiosteal approach in microdiscectomy. The microendoscopic discectomy (MED) was the first technique addressing this shortcoming of the conventional subperiosteal interlaminar approach [10, 13, 16]. MED performed via a blunt muscle splitting approach, is characterised by less postoperative pain, shorter hospitalisation and faster return to work [10]. However, limitations of the MED-technique are the steep learning curve and the lack of a stereoscopic view. That led to the development of the METRx-modification, which addressed the surgical community familiar with the microscope [13]. However, the rigid tubular retractor required a soft tissue opening, which equalled the surgical target area.

The aim of this prospective randomised study was to compare the clinical outcome and the analgesic consumption of patients after lumbar microdiscectomy performed via a miniaturized transmuscular approach (TM) using an expandable tubular retractor (Microdisc-XS, Medicon, Tuttlingen, Germany) with a control group operated on via the conventional subperiosteal approach (SP) using a Caspar speculum (Aesculap, Tuttlingen, Germany).

Materials and methods

Between July 2003 and March 2005, 141 patients scheduled for first time lumbar microdiscectomy were enrolled in the study. Surgery was proposed when conservative treatment had failed after 12 weeks or when progressive neurological deficits burdened the patients. The patients were randomised by calendar date and blinded to the type of approach used. The informed consent was given for “lumbar microdiscectomy”. The procedures were performed by two experienced surgeons.

Unexpected intraoperative findings such as synovial cysts (4) and lymphoma (1) led to exclusion. Patients in which the disc herniation was combined with a relevant lateral recess stenosis requiring substantial facet joint drilling were also excluded (11). The data of 125 patients following discectomy or fragmentectomy were collected prospectively.

Each patient completed a “visual analogue scale” (VAS) form for back and leg pain before surgery and daily up to 6 days after surgery. An “Oswestry disability index”—questionnaire (ODI, German Version 2.0) [5] was filled in before surgery and at dismission. The length of hospitalisation was due by the reimbursement policy at that time. For better comparison of our results with other studies the mean VAS-values at discharge were divided into “success” (VAS 0–4), comprehensive of excellent (VAS 0–1) and satisfactory (VAS 2–4) results and into “failure” (VAS 5–10).

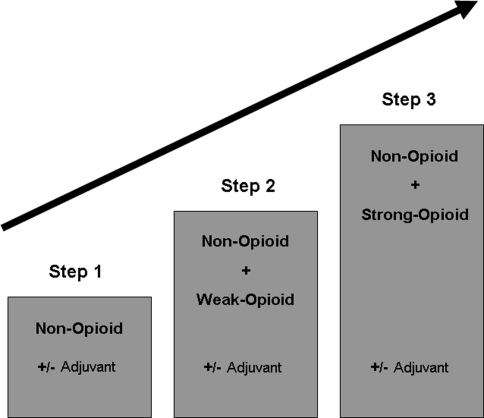

The consumption of analgesics during the hospital staying was scored according to the WHO protocol (Fig. 1). This guideline defines 3 classes of drugs: class 1 encloses non-opioids, mostly NSAR, drugs; in class 2, a weak opioid is added to class 1 drugs and class 3 means the combination of non-opioids with strong opioids [17]. Each patient was treated the first day after surgery with class 1 drugs. The further drug administration was however, adapted to the demand of the patient. Each increase in class was scored as an additional “analgesic-point”. Furthermore, a 1/3 point (class 1), 2/3 point (class 2) and 1 point (class 3) was added for each on-demand drug intake beyond the scheduled pain-medication.

Fig. 1.

WHO pain relief ladder

The data were analysed with SigmaPlot® (version 8.0) and SigmaStat® (version 2.03, SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA). The difference of clinical outcome and drug intake was assessed by the student T test. A P value <0.05 was regarded as statistical significant.

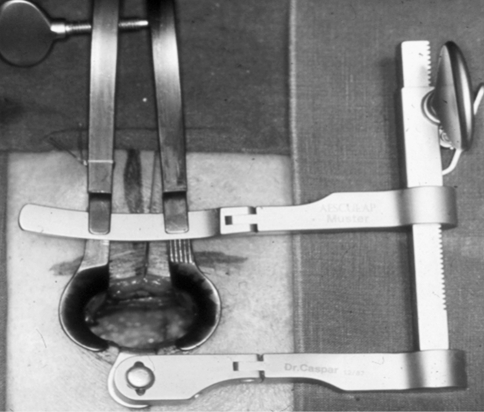

Surgical technique: the subperiosteal approach

The patient is positioned under general anaesthesia prone on the “Wilson”-frame. The target disc is identified by fluoroscopic control. With the aid of the microscope a 3 cm skin incision is made 1 cm off the midline. The fascia is incised in an arcuate fashion and the medial lip suspended with two stitches towards the midline. The tendineous insertions of multifidus muscle and of erector spinae muscle are incised and the muscles dissected bluntly subperiosteally from the spinous process and from the lower border of the lamina. The speculum-counter-retractor is inserted (Fig. 2). A fluoroscopic control is performed in order to confirm the right level of discectomy. Incision of the yellow ligament and further steps are those of conventional microsurgical discectomy.

Fig. 2.

Caspar-retractor with counter-retractor in situ

Surgical technique: the transmuscular approach

Positioning and radiographic labelling are the same as previously described. Differently from the subperiosteal technique a skin-incision of 17–18 mm is made 2 cm lateral off the midline with the aid of the microscope. The fascia is incised straight and both lips are suspended with two stitches. The surgeon splits bluntly with his index finger the muscles slightly convergent until palpating the lamino-facet junction. Two slim soft tissue holders are introduced. An expandable tubular retractor of appropriate length is inserted and opened like an inverted cone: the superficial diameter is 15 mm and the deep one 24 mm. The tube is fixed to a flexible holder arm (Figs. 3, 4). The disc level is checked by fluoroscopy. The further surgical steps are identical with the microsurgical subperiosteal technique.

Fig. 3.

XS-tubular retractor in situ anchored to a flexible holder arm

Fig. 4.

Postoperative consumption of analgesics—mean values and standard deviation for SP (n = 56) and TM-group (n = 63)

Results

Fifty-nine patients were operated on via the SP and in 66 patients the TM route was used. In both groups the mean age was 51 years (range 20–79 years). The mean age was slightly increased by 13 patients (8 TM and 5 SP) in their seventies, but in excellent general conditions. The male gender was prevalent (61%) in both groups, the distribution of the operated levels and the ratio discectomy/fragmentectomy were also similar.

Visual analogue scale

Leg-pain

The intensity of preoperative leg pain was similar in all patients (SP 7.5; TM 7.3). One-day after surgery the mean values decreased to 2.1 in the SP-group and to 2.2 in the TM-group. The lowest VAS-score was reached at dismissal: 1.4 (SP) and 0.9 (TM). TM-patients of 75.8% (n = 50) and 67.8% (n = 40) of the SP-patients were pain free (VAS 0–1) at dismission. On the whole, 97% (n = 64) of TM-patients and 91.5% (n = 54) of SP-patients defined the outcome of their operation as a “success” (VAS < 4). The difference between the groups was not significant (P = 0.47). An only marginal or not at all improvement of pain was defined as “failure” for the purpose of this study. However, it should be noticed that later on in the follow-up some of the “early failure”—patients recovered as well so that the overall “1-year failure” rate was 3% in both groups.

Back-pain

The preoperative back-pain was significantly more intense (VAS 6) in the SP-group than in the TM-group (VAS 4.9). Following surgery the VAS-score decreased to 1.7 (SP) and to 1.2 (TM). Before discharge, 57.6% (n = 34) of SP-patients and 59.1% (n = 39) of TM-patients were “back-pain free”. As it was expected, these figures compared less favourably with that of the postoperative decrease of leg pain. On the whole, 95.5% (n = 63) of the TM-patients and 94.9% (n = 56) of the SP-patients defined the outcome of their operation as a “success” (VAS < 4). The difference between the groups was not significant.

Oswestry disability index

The preoperative median Oswestry disability index (ODI) was 57.1% in the SP-group and 52.8% in the TM-group. The difference was not significant. The patients filled in the questionnaire again before leaving the hospital. The postoperative ODI-score of SP-patients improved to 20% compared to 25.7% of the TM-patients. The improvement of the postoperative ODI-score was significant in both groups but no difference was observed between the groups. Gender, age of the patient, location of the disc herniation and duration of surgery did not correlate as prognostic factors with the ODI-score.

Postoperative consumption of analgesics

The SP-patients needed over the period of six postoperative days an analgesic medication according to the WHO protocol amounting to mean 4.8 points. The TM-patients took in drugs corresponding to mean 2.6 points. The difference was significant (P = 0.03). Similarly to the analysis of the ODI-score, no other variables influencing the postoperative consumption of analgesics could be found.

Discussion

Microsurgical discectomy was introduced independently by Yasargil [19] and Caspar [4] in 1977 and by Williams in 1978 [18]. Basically, all three variants share the miniaturized subperiosteal approach to the interlaminar window. The advantages of microdiscectomy are decreased soft-tissue traumatization, blood loss and overall-morbidity due to the magnification and illumination provided by the microscope [10]. Andrews summarized the advantages of the Caspar-type microdiscectomy in comparison with the conventional macrodiscectomy as less need of postoperative analgesics, shorter hospitalisation and faster return to work [1]. The 10-year follow-up after microdiscectomy based on the “Roland-Morris-score” and on the patient satisfaction showed a success-rate of ranging from 85 to 91% [3, 6]. Microdiscectomy is still the gold standard for open surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniation. The METRx-technique introduced by Smith and Foley in 1997 represented a refinement of the procedure [16].

The METRx-technique combines the insertion of a rigid tubular retractor via a transmuscular route for a microsurgical interlaminar approach to the disc herniation. A comparative study of METRx with conventional microdiscectomy showed a significant faster return to work for the new procedure [12]. Furthermore, an intraoperative EMG-study done by Schick demonstrated that the transmuscular route damages the paraspinal muscles less than the subperiostal approach [14]. This is in accordance with the observation of Kim et al., which reported a decrease of the cross sectional area of spinal muscles on MRI after open pedicle screw fixation, but no decrease after use of percutaneous pedicle screw osteosynthesis [8]. Furthermore, Kawaguchi et al. reported a substantial increase in intramuscular pressure of the erector spinae by opening of self-retaining retractors. He hypothesized that the applied pressure resulted in the observed postoperative lesions [7]. The preliminary data of an ongoing study in our department show that the mean pressure applied at the interface between the counter-retractor of the Caspar type speculum and muscle is 110 ± 28 mmHg compared with 30 ± 12 mmHg at the interface between the openend expandable tubular retractor and muscle (P < 0.001). Ogata reported that lesions can develop in skeletal muscle after pressures as low as 30 mm Hg [11].

To our best knowledge, the present is the first prospective randomized study comparing the transmuscular approach using an expandable tubular retractor with the conventional microdiscectomy requiring a subperiosteal approach. In 2005 Schizas [15] divided nonrandomly 28 patients in 2 groups, which were operated via a transmuscular or a subperiosteal approach. The postoperative scores of the “Oswestry-disability-questionnaire” and of a score for back-pain did not differ significantly. However, the patients operated through the transmuscular approach needed significantly less pain medication.

Our results referring to larger groups of patients support the evidence that the transmuscular approach to the interlaminar window is as effective as the conventional microsurgical route requiring the subperiosteal muscle retraction. This should be expected, because the postoperative scores mostly reflect the decompression of the root, which is identical in both techniques. The explanation of the significantly less postoperative consumption of analgetics is up to now temptative, but seems to be linked to the decreased intramuscular pressure of the transmuscular approach. That could mean less ischemic damage of the muscle tissue and less release of pain mediating substances.

Conclusion

In this study the conventional lumbar microsurgical subperiosteal and a more recent transmuscular approach to the interlaminar window were compared. The early postoperative outcome after disc surgery assessed with back- and leg-pain VAS and ODI was equivalent in both groups. The consumption of analgesics was significantly less in patients operated on via the transmuscular route.

Contributor Information

Marko Brock, Phone: +49-40-87973707, Email: marko.brock@marienhospital-herne.ode.

Philip Kunkel, Email: philip.kunkel@kinderkrankenhaus.net.

Luca Papavero, Email: LPapavero@schoen-kliniken.de.

References

- 1.Andrews DW, Lavyne MH. Retrospective analysis of microsurgical and standard lumbar discectomy. Spine. 1990;15(4):329–335. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199004000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asch HL, Lewis PJ, Moreland DB, Egnatchik JG, Yu YJ, Clabeaux DE, Hyland AH. Prospective multiple outcomes study of outpatient lumbar microdiscectomy: should 75–80% success rates be the norm? J Neurosurg. 2002;96(1 Suppl):34–44. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.96.1.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrios C, Ahmed M, Arrotegui J, Bjornsson A, Gillstrom P. Microsurgery versus standard removal of the herniated lumbar disc. A 3-year-comparison in 150 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61(5):399–403. doi: 10.3109/17453679008993549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caspar W. A new surgical procedure for the lumbar herniation causing less tissue damage through a microsurgical approach. Adv Neurosurg. 1977;4:74–77. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O’Brien JP. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66(8):271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Findlay GF, Hall BI, Musa BS, Oliveira MD, Fear SC. A 10-year follow-up of the outcome of lumbar microdiscectomy. Spine. 1998;23(10):1168–1171. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199805150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawaguchi Y, Matsui H, Tsuji H. Back muscle injury after posterior lumbar spine surgery. A histologic and enzymatic analysis. Spine. 1996;21(8):941–944. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199604150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim DY, Lee SH, Chung SK, Lee HY. Comparison of multifidus muscle atrophy and trunk extension muscle strength: percutaneous versus open pedicle screw fixation. Spine. 2005;30(1):123–129. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000157172.00635.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu K, Liang CL, Cho CL, Chen HJ, Hsu HC, Yiin SJ, Chern CL, Chen YC, Lee TC. Oxidative stress and heat shock protein response in human paraspinal muscles during retraction. J Neurosurg. 2002;97(1 Suppl):75–81. doi: 10.3171/spi.2002.97.1.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maroon JC. Current concepts in minimally invasive discectomy. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(5 Suppl):S137–S145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogata K, Whiteside LA (1982) Effects of external compression on blood flow to muscle and skin. Clin Orthop Relat Res (168):105–107 [PubMed]

- 12.Palmer S. Use of a tubular retractor system in microscopic lumbar discectomy: 1-year prospective results in 135 patients. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;13(2):E5. doi: 10.3171/foc.2002.13.2.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ranjan A, Lath R. Microendoscopic discectomy for prolapsed lumbar intervertebral disc. Neurol India. 2006;54(2):190–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schick U, Dohnert J, Richter A, Konig A, Vitzthum HE. Microendoscopic lumbar discectomy versus open surgery: an intraoperative EMG study. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(1):20–26. doi: 10.1007/s005860100315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schizas C, Tsiridis E, Saksena J. Microendoscopic discectomy compared with standard microsurgical discectomy for treatment of uncontained or large contained disc herniations. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(4 Suppl):357–360. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.00000176650.71193.F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith M, Foley K. Microendoscopic discectomy. Tech Neurosurg. 1997;3:301–307. [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO Cancer pain relief and palliative care. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1990;804:1–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams RW. Microlumbar discectomy: a conservative surgical approach to the virgin herniated lumbar disc. Spine. 1978;3(2):175–182. doi: 10.1097/00007632-197806000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yasargil MG. Microsurgical operation of herniated lumbar disc. Adv Neurosurg. 1977;4:81–88. [Google Scholar]