Abstract

The residue environment in protein structures is studied with respect to the density of carbon (C), oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N) atoms within a certain distance (say 5 Å) of each residue. Two types of environments are evaluated: one based on side-chain atom contacts (abbreviated S-S) and the other based on all atom (side-chain + backbone) contacts (abbreviated A-A). Different atom counts are observed about nine-residue structural categories defined by three solvent accessibility levels and three secondary structure states. Among the structural categories, the S-S atom count ratios generally vary more than the A-A atom count ratios because of the fact that the backbone (O) and (N) atoms contribute equal counts. Secondary structure affects the (C) density for the A-A contacts whereas secondary structure has little influence on the (C) density for the S-S contacts. For S-S contacts, a greater density of (O) over (N) atom neighbors stands out in the environment of most amino acid types. By contrast, for A-A contacts, independent of the solvent accessibility levels, the ratio (O)/(N) is ≈1 in helical states, consistent with the geometry of α-helical residues whose side-chains tilt oppositely to the amino to carboxy α-helical axis. The highest ratio of neighbor (O)/(N) is achieved under solvent exposed conditions. This (O) vs. (N) prevalence is advantageous at the protein surface that generally exhibits an acid excess that helps to enhance protein solubility in the cell and to avoid nonspecific interactions with phosphate groups of DNA, RNA, and other plasma constituents.

Keywords: residue associations, oxygen, nitrogen

This paper continues our studies of measures of residue densities in protein structures centering on the atom density about different amino acid (aa) types (cf. 1). For a representative protein structure data set, we assess various atom densities, including the average number of carbon (C), oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N) atoms within a 5-Å neighbor of each amino acid type. The amino acids in the proteins are divided into nine structural categories (SCs) characterized by three secondary structure (Ss) states (helix, strand, coil) and three solvent accessibility levels (Sa) (ref. 1; see references therein for other perspectives on density packing). The Sa division is: buried (bu) if Sa ≤ 10%, partly buried (pb) if 10% < Sa ≤ 40%, and exposed (ex) if 40% < Sa. The nine SCs are abbreviated α-bu, α-pb, α-ex, β-bu, β-pb, β-ex, c-bu, c-pb, and c-ex. Let (aa, SC) refer to a specific amino acid and its structural category. The unconditioned state signifies an amino acid ignoring its SC.

With each amino acid (aa) and SC, we determine a (C), (O), and (N) atom density of two kinds. First, for all residues of the protein structures, we count (C) atoms from residue side-chains within 5 Å of some side-chain atom of the (aa, SC) residue. (For glycine, the side-chain is defined as its Cα carbon). The (C) total count in the prescribed neighborhood of an (aa, SC) type is denoted by Ccum(aa, SC). The number of (aa, SC) type residues in our protein structure set is denoted by K(aa, SC). Then, C(aa, SC) = Ccum(aa, SC)/K(aa, SC) assesses the (C) atom density for the amino acid type (aa, SC). These density measurements of side-chain atom contacts are labeled S-S. In an analogous way, we calculate the (O) and (N) atom densities, O(aa, SC) and N(aa, SC), respectively. Normalized densities are also determined to accommodate the various sizes and shapes of amino acids. We further consider for each (aa, SC) type the numbers of (C), (O), and (N) (backbone and side-chain) atoms within 5 Å of any (backbone and side-chain) atom of the (aa, SC) residue [designated all-all (A-A) contacts]. The atom density analysis can be extended to sulfur atoms, water units, and other molecules (e.g., porphyrin, ATP) embedded in protein structures.

The following questions, inter alia, are investigated. How are size, shape, charge, and hydrophobicity properties of the different (aa, SC) types reflected in the different atom densities? When is the (O) atom density vs. the (N) atom density greater or less? Are there differences in (O) density for hydroxyl, carboxylates, or carbonyl? Are there differences in (N) density for guanidinium, imidazole, or localized groups? How do secondary structure states and solvent accessibility levels impact these atom densities?

Methods

In this study, we use a representative set of 418 globular protein structures with pairwise sequence identity lower than 25%. The PDB codes are listed as supplemental material on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org.

Atom Density Calculations.

For each protein structure S and each amino acid type (aa, SC), let OS(aa, SC) be the number of (O) side-chain atoms within 5 Å of any side-chain atom of the (aa, SC) residue in structure S. Set Ocum(aa, SC) = ΣSOS(aa, SC). Let K(aa, SC) be the count of (aa, SC) residue types of the data set. Then, O(aa, SC) = Ocum(aa, SC)/K(aa, SC) is the (O) density about (aa, SC) residue types.

Let n*(aa) be the number of side-chain atoms of the specific amino acid aa: e.g., n*(Ala) = 1, n*(Lys) = 5, n*(Arg) = 7. Then, O*(aa, SC) = O(aa, SC)/n*(aa) can be interpreted as the normalized (O) density of (aa, SC) per side-chain atom. By similar means, we tabulate N(aa, SC) and N*(aa, SC) for (N) atoms and C(aa, SC) and C*(aa, SC) for (C) atoms. Other normalizations dividing by amino acid side-chain surface area or volume produce measures with results qualitatively similar to C*, O*, and N*. The total density of atoms is obtained by summing C(aa, SC) + O(aa, SC) + N(aa, SC). The unconditional counts result by aggregating the SCs leading to Ccum(aa, total) = ΣSCCcum(aa, SC), Ocum(aa, total), Ncum(aa, total) and the unconditional densities are C(aa, total) = Ccum(aa, total)/K(aa, total), and similarly for O(aa, total) and N(aa, total), where obviously K(aa, total) = ΣSCK(aa, SC). The average (O) [or (C) or (N)] density O(SC) for a given structural category (SC) is the sum of Ocum(aa, SC) over all amino acids of structural category SC divided by the count of all amino acids belonging to SC. Thus, O(SC) = ΣaaOcum(aa, SC)/ΣaaK(aa, SC).

We also calculate the (O) to (N) density ratio for the purpose of comparing affinity for (O) vs. (N) atoms, namely ρ(aa, SC) = Ocum(aa, SC)/Ncum(aa, SC). Similarly, we obtain an average ρ(SC) ratio by summing Ocum(aa, SC) and Ncum(aa, SC) values over all amino acids aa, namely ρ(SC) = ΣaaOcum(aa, SC)/ΣaaNcum(aa, SC).

Results

Residue Atom Densities of Side-Chain (S-S) Interactions.

We ascertain neighbor counts [cumulative, average, and normalized (see Methods)] of (C), (O), and (N) atoms of residue side-chains within 5 Å of any side-chain atom of a prescribed residue type. The results are given in Table 1 that also displays contrasts in the (O) to (N) neighbor atom counts.

Table 1.

Residue atom densities of side-chain contacts

| SC | No. | C | O | N | ρ | T | No. | C | O | N | ρ | T | No. | C | O | N | ρ | T | No. | C | O | N | ρ | T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asp (4 side-chain atoms) | Glu (5) | Arg (7) | Lys (5) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| α-bu | 290 | 13.3 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 0.70 | 17.6 | 335 | 14.9 | 2.1 | 2.6 | 0.79 | 19.6 | 320 | 16.9 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 1.93 | 22.0 | 139 | 13.7 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 2.60 | 18.0 |

| β-bu | 264 | 13.3 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 0.89 | 17.8 | 206 | 14.9 | 2.2 | 2.7 | 0.83 | 19.7 | 227 | 17.5 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 2.02 | 23.0 | 113 | 14.3 | 3.2 | 1.0 | 3.25 | 18.4 |

| c-bu | 630 | 13.3 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 0.91 | 17.7 | 304 | 14.9 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 0.87 | 20.0 | 329 | 16.8 | 3.6 | 2.1 | 1.72 | 22.4 | 132 | 13.5 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 2.17 | 18.5 |

| α-pb | 403 | 9.4 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 0.60 | 13.1 | 750 | 10.0 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 0.62 | 13.4 | 810 | 11.4 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 2.76 | 15.3 | 608 | 9.4 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 2.98 | 12.6 |

| β-pb | 276 | 9.3 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 0.86 | 12.8 | 433 | 10.0 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 0.61 | 13.3 | 509 | 12.7 | 2.9 | 1.1 | 2.67 | 16.6 | 456 | 10.1 | 2.6 | 0.8 | 3.37 | 13.4 |

| c-pb | 1022 | 9.8 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 0.81 | 13.1 | 631 | 10.6 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 0.78 | 14.3 | 881 | 11.9 | 2.8 | 1.3 | 2.21 | 16.0 | 696 | 9.3 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.64 | 12.5 |

| α-ex | 997 | 4.4 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.67 | 6.4 | 1824 | 4.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.74 | 6.8 | 875 | 6.1 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 3.17 | 8.5 | 1526 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 3.41 | 6.4 |

| β-ex | 250 | 5.1 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.81 | 7.0 | 493 | 5.5 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 0.66 | 7.5 | 354 | 7.0 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 2.81 | 9.5 | 617 | 5.5 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 4.11 | 7.5 |

| c-ex | 2707 | 5.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.09 | 6.8 | 1982 | 4.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.95 | 6.6 | 1121 | 5.9 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 2.53 | 8.2 | 2407 | 4.6 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 2.73 | 6.5 |

| To | 6839 | 7.5 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.85 | 10.2 | 6958 | 7.5 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.77 | 10.1 | 5426 | 10.2 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 2.39 | 13.7 | 6694 | 6.5 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 2.97 | 8.90 |

| Leu (4) | Met (4) | Ile (4) | Val (3) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| α-bu | 2580 | 15.4 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.34 | 17.0 | 619 | 16.8 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.25 | 18.5 | 1363 | 15.6 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.41 | 17.3 | 1416 | 13.4 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.39 | 14.9 |

| β-bu | 1874 | 16.1 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.45 | 17.4 | 424 | 16.3 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.41 | 18.0 | 1859 | 15.9 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.50 | 17.2 | 2447 | 13.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.45 | 14.7 |

| c-bu | 1739 | 15.6 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.32 | 17.8 | 405 | 16.1 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.34 | 18.8 | 938 | 15.7 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.39 | 18.0 | 1185 | 13.0 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.44 | 15.0 |

| α-pb | 916 | 10.5 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.12 | 12.6 | 248 | 10.9 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.07 | 12.9 | 475 | 10.9 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.34 | 13.1 | 461 | 9.3 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.36 | 11.2 |

| β-pb | 440 | 10.7 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.38 | 12.6 | 101 | 10.9 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.43 | 12.8 | 429 | 10.7 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.30 | 12.7 | 602 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.26 | 10.8 |

| c-pb | 966 | 10.5 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.36 | 12.8 | 274 | 10.9 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.35 | 13.3 | 553 | 10.7 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.40 | 13.0 | 736 | 9.2 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.36 | 11.3 |

| α-ex | 359 | 5.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.28 | 6.8 | 88 | 5.4 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.31 | 6.6 | 168 | 5.6 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.40 | 7.4 | 269 | 4.5 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.66 | 6.1 |

| β-ex | 159 | 5.9 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.94 | 7.1 | 55 | 5.7 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 2.08 | 7.0 | 144 | 5.9 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.41 | 7.8 | 263 | 5.0 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.88 | 6.3 |

| c-ex | 603 | 4.9 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.67 | 6.5 | 217 | 4.7 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.44 | 5.9 | 381 | 5.6 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.57 | 7.2 | 645 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.57 | 5.9 |

| To | 9636 | 13.2 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.35 | 14.9 | 2431 | 13.3 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.32 | 15.3 | 6310 | 13.5 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.42 | 15.3 | 8024 | 11.1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.43 | 12.7 |

| His (6) | Phe (7) | Trp (10) | Tyr (8) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| α-bu | 244 | 15.7 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 1.52 | 19.5 | 924 | 19.6 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.41 | 21.7 | 295 | 22.9 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.28 | 26.0 | 590 | 20.4 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.30 | 24.0 |

| β-bu | 246 | 15.4 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 1.59 | 19.6 | 1072 | 19.1 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.35 | 20.9 | 289 | 21.6 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.51 | 24.5 | 729 | 19.5 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.39 | 23.0 |

| c-bu | 341 | 15.6 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 1.51 | 20.0 | 918 | 19.2 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.28 | 22.1 | 358 | 21.4 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.22 | 25.5 | 609 | 19.5 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 1.16 | 24.0 |

| α-pb | 222 | 11.3 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.67 | 14.1 | 327 | 14.0 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.27 | 16.6 | 184 | 17.0 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.14 | 20.7 | 471 | 14.8 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.22 | 18.2 |

| β-pb | 218 | 11.4 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1.73 | 14.6 | 297 | 13.1 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.42 | 15.5 | 170 | 15.5 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.24 | 18.9 | 506 | 13.5 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.37 | 16.5 |

| c-pb | 469 | 11.4 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.63 | 14.6 | 589 | 13.5 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.19 | 16.8 | 255 | 16.1 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 1.12 | 20.2 | 724 | 14.3 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.34 | 18.2 |

| α-ex | 190 | 5.5 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.76 | 7.4 | 116 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.07 | 8.8 | 39 | 8.4 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.28 | 10.8 | 154 | 7.9 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1.45 | 10.0 |

| β-ex | 104 | 6.4 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 2.86 | 8.6 | 104 | 7.2 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.45 | 8.8 | 30 | 9.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.06 | 11.8 | 132 | 8.1 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.37 | 10.4 |

| c-ex | 538 | 5.3 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.97 | 7.2 | 325 | 6.5 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.52 | 8.3 | 107 | 8.6 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.66 | 11.0 | 369 | 7.5 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.43 | 9.9 |

| To | 2572 | 10.8 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.67 | 13.9 | 4672 | 16.3 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.31 | 18.7 | 1727 | 18.6 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.26 | 22.0 | 4284 | 15.7 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.30 | 19.2 |

| Ser (2) | Thr (3) | Asn (4) | Gln (5) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| α-bu | 597 | 10.0 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.68 | 12.0 | 628 | 12.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.51 | 14.9 | 259 | 13.4 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.42 | 16.8 | 276 | 15.2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.33 | 18.6 |

| β-bu | 657 | 9.8 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.57 | 12.1 | 768 | 12.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.54 | 14.4 | 271 | 12.5 | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1.70 | 15.8 | 207 | 14.9 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 1.26 | 18.4 |

| c-bu | 1069 | 9.8 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 1.78 | 12.5 | 974 | 12.1 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.67 | 15.0 | 610 | 13.2 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 1.59 | 16.7 | 250 | 14.8 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 1.59 | 18.5 |

| α-pb | 341 | 6.5 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.50 | 8.3 | 367 | 8.7 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.24 | 10.9 | 360 | 9.8 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.36 | 12.4 | 477 | 10.2 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.33 | 13.0 |

| β-pb | 377 | 6.3 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.62 | 8.4 | 590 | 7.8 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.64 | 10.1 | 227 | 9.5 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 1.75 | 12.4 | 261 | 10.3 | 1.6 | 1.1 | 1.51 | 12.9 |

| c-pb | 984 | 7.1 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.76 | 9.2 | 841 | 8.7 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 1.73 | 11.2 | 808 | 9.7 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 1.70 | 12.7 | 476 | 10.5 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.40 | 13.6 |

| α-ex | 672 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 1.74 | 4.0 | 520 | 4.1 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.63 | 5.7 | 598 | 4.6 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.26 | 6.2 | 881 | 5.2 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.74 | 7.0 |

| β-ex | 326 | 3.3 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 2.30 | 4.5 | 538 | 4.3 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 2.38 | 5.6 | 245 | 5.1 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 2.19 | 7.1 | 280 | 5.5 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.58 | 7.1 |

| c-ex | 2178 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 0.4 | 2.79 | 4.8 | 1706 | 4.2 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 2.37 | 5.9 | 2117 | 4.7 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.90 | 6.5 | 1185 | 4.9 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.53 | 6.5 |

| To | 7201 | 6.2 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 1.90 | 8.1 | 6932 | 8.0 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.75 | 10.1 | 5495 | 7.7 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.66 | 10.1 | 4293 | 8.3 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.48 | 10.6 |

The average counts of carbon (C), oxygen (O), and nitrogen (N) atoms and all atoms (T) are reported (see Methods) for each of the nine structural categories (SCs) of 16 amino acids. The results for the four amino acids Gly, Ala, Cys, Pro are provided in the supplemental material available on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org. The SCs are α-buried (α-bu), α-partly buried (α-pb), α-exposed (α-ex), β-buried (β-bu), β-partly buried (β-pb), β-exposed (β-ex), coil-buried (c-bu), coil-partly buried (c-pbu), coil-exposed (c-ex). “To” gives values for the unconditional state. “No.” gives the number of aa. in each SC. The ρ values (ratio of the oxygen 5-Å neighbor numbers and the nitrogen 5-Å neighbor numbers) are given.

Charge residues.

Occurrences of Glu and Asp are almost equally frequent in protein structures, although Glu favors helical locations whereas Asp is prevalent in coil locations. The 5Å neighboring average counts of (C), (O), and (N) atoms covering the two acidic residues are about equal. The ρ(Glu, SC) range is 0.61–0.95, and the ρ(Asp, SC) range is 0.60–0.91 except 1.09 in the coil-exposed state. Contributing to these counts are salt-bridge formations, metal coordination by acidic ligands in proximity with histidine ligands, and frequent appearances of Asp (more than Glu) at active sites of protease and kinase enzymes (2). Asp achieves its smallest ρ values in the α state and largest in the coil state.

The data set contains more Lys residues (6694) than Arg residues (5426) but significantly greater neighbor counts of (C), (O), and (N) atoms per Arg than per Lys. In fact, the 5Å neighbor (C) side-chain atoms on average per Lys has C(Lys) = 6.46 whereas C(Arg) = 10.22. Thus, on average, Arg is surrounded by many more (C) than is Lys. Multiplying by the factor (7/5) produces the normalized ratio C*(Lys)/C*(Arg) = 0.88, indicating a greater normalized density of (C) atoms about Arg vs. Lys. This may be puzzling because Lys possesses four side-chain methylene groups compared with three methylene groups for Arg. However, Lys tends to be more solvent exposed than Arg and from this vantage less in contact with (C) atoms. The same holds for (O) atoms. However, N*(Lys)/N*(Arg) ≈ 1, consistent with the property that Arg more than Lys repels (N) atoms.

It is interesting to contrast (O) to (N) atom neighbors about Lys and Arg assessed by ρ(Lys, SC) and ρ(Arg, SC). These contrasts for every SC exceed 2, indicating more than twice as many (O) to (N) atoms in a 5Å neighborhood about cationic residues. This could be expected because Lys and Arg commonly establish salt-bridges with the Glu and Asp carboxylates and form hydrogen bonds with Asn, Gln and with the hydroxyl groups of Ser, Thr, and Tyr. Strikingly, for each SC, ρ(Lys, SC) ≫ ρ(Arg, SC) ≫ 1. These inequalities convey a persistent side-chain affinity for (O) atoms compared with (N) atoms and greater contrasts about Lys than about Arg. A dramatically high ρ ratio occurs in the β-ex state for Lys whereas the greatest ρ ratio for Arg is in the α-ex state (Table 1). These contrasts are consistent with the greater propensity of Lys vs. Arg for exposed positions (3). The persistent inequality ρ(Lys, SC) ≫ ρ(Arg, SC) relative to side-chain atom contacts suggests that the dispersed (N) of the guanidinium group of Arg is easily accessible for bonding to (O) atoms whereas the localized charge of Lys may require an (O)-rich environment to neutralize its charge.

Asp and Glu exhibit stronger attractions for Arg than for Lys. Contributing factors may include (i) the delocalized charge enveloping Arg compared with a localized charge for Lys and Arg is a much stronger base (higher pKa) than Lys; (ii) diverse posttranslational modifications of Lys compared with Arg: e.g., Lys is frequently acetylated, Arg never; (iii) Arg tends to be coupled to an acidic residue in a buried state whereas Lys commonly extends to the surface with its side-chain amino group exposed. In this context, Arg reflects more relative hydrophobicity.

His.

The two (N) in the imidazole of His frequently make contacts with side-chain (O) atoms of acidic and hydroxyl residues. Moreover, His residues often coordinate metal sites and participate regularly in active site function (e.g., protease and kinase structures) (4). The greatest (O) atom density about His occurs in β strand locations, and in absolute counts His is mostly found in coil SCs. Histidine strongly favors (O) over (N) atom neighbors, generally 1.5 ≤ ρ(His, SC) ≤ 1.97.

Aliphatics.

The overall neighbor counts of (C) on average for the aliphatic residues {Ile, Val, Leu, Met} are 13.5, 11.1, 13.2, and 13.3, respectively. Corresponding to (O), we obtain 1.1, 0.9, 1.0, and 1.1 and for (N) 0.8, 0.7, 0.8, and 0.8. The largest value of the (O)/(N) ratio is always achieved in buried states and subtend the ranges: ρ(Ile) 1.30–1.57, ρ(Val) 1.26–1.88, ρ(Leu) 1.12–1.94, ρ(Met) 1.07–1.44 (one value 2.08). Comparing Ile versus Val and Leu versus Met of similar sizes, the aggregate neighbor counts of (C) atoms show Ccum(Ile)/Ccum(Val) = 0.95, Ccum(Leu)/Ccum(Met) = 3.9 whereas the ratios evaluated per amino acid give C(Ile)/C(Val) = 1.2 and C(Leu)/C(Met) = 0.99, indicating somewhat opposite tendencies. We also obtain O(Ile)/O(Val) = 1.13, N(Ile)/N(Val) = 1.14 and in normalized forms O*(Ile)/O*(Val) = 0.85 and N*(Ile)/N*(Val) = 0.85. In side-chain contacts, Met among aliphatic residues registers the high value ρ(Met) = 2.08 in the β-ex state. This may portend a special role for the sulfur side-chain atom in proximity to (O) atoms. For example, Met is known to be fundamental in copper type I metal coordination and in electron transfer pathways (5).

Aromatics.

More than 75% of Phe residues act as hydrophobic and are dense with neighboring (C) atoms, C(Phe) = 16.3 and almost the same for Tyr, C(Tyr) = 15.7. The (C) mean density is 18.6 for Trp. The O(Phe) average count is 1.4, O(Tyr) = 2.0 and O(Trp) = 1.9. Similarly, the average (N) counts are N(Phe) = 1.0, N(Tyr) = 1.5, N(Trp) = 1.5. For Phe versus Tyr, the ratio of (C) atom counts per amino acid is effectively 1.0. For Phe versus Trp, we obtain a 0.88 ratio, indicating a greater (C) density about Trp compared with Phe, and, when normalized by side-chain atom numbers, the ratio is 1.26, reversing the inequality. The (O) vs. (N) counts per amino acid ratios for Phe and Trp gives 0.70 and 0.67, respectively.

In comparing ρ values, we have overall ρ(Trp) = 1.26, indicating moderate preference of (O) to (N) and, similarly, ρ(Tyr) = 1.30 and ρ(Phe) = 1.31. The ρ distributions for each Sa level differ with respect to Ss states among Phe, Tyr, and Trp. For example, at the buried level, ρ(Phe) is highest in the α state whereas ρ(Tyr) and ρ(Trp) are highest in the β state. At the partly buried level, all three aromatics have ρ highest in the β state. At the exposed level, ρ(Phe) and ρ(Trp) show the highest value in the coil state whereas ρ(Tyr) is highest in the α state. Aromatic residues emphasize Arg among their over-represented neighbors whereas Lys tends to be under-represented. In this respect, the fact that only Arg (not Lys) has a favorable cation-aromatic interaction with Tyr and Trp may be decisive (6). Lys is generally disposed to aromatic residues via a more standard hydrophobic interaction of its methylene groups.

Small hydroxyls.

Thr rather than Ser is more densely surrounded with (C) atoms to the extent that, in raw counts, Ccum(Ser)/Ccum(Thr) = 0.81, and, because there are more Ser than Thr, C(Ser)/C(Thr) = 0.78. In normalizing by the side-chain number, we obtain C*(Ser)/C*(Thr) = 1.17. Similar results prevail in comparing (O) and (N) atom densities (Table 1). The ratios ρ(Ser, SC) range from 1.50 to 2.79, and the highest achieved in the β-ex and c-ex states are 2.30 and 2.79, respectively. The evaluations ρ(Thr, SC) parallel those for Ser. The side-chain contacts of Ser and Thr emphasize acidic and histidine residues as nearest neighbors consistent with the results on ρ values. Ser is also a vital residue coupled with Asp and His at active sites of many protein families (7). In the side-chain environment of Ser and Thr, we have ρ(Ser)>ρ(Thr)>1 for every SC, indicating that (O) atoms are favored neighbors over (N) atoms and more emphatic for Ser, possibly because Ser more than Thr contributes at active sites of protease functions. For Ser and Thr, the highest (O) and (N) average counts are in the coil state, where active sites tend to be located.

Amides.

The ρ ratio (mostly between 1.26 and 2.19) clearly favors (O) to (N) atoms, implicating more interactions with acidic rather than with basic residues and/or apparently greater numbers of H-bonding interactions with hydroxyl and tyrosine residues. Asn is more frequent than Gln, i.e., the ratio K(Asn)/K(Gln) = 1.28. The (C) neighbor counts is greater for Gln than for Asn.

Cys.

Cysteine is important in some patterns of zinc and copper coordination, in stabilizing iron-sulfur clusters and in covalent attachments to heme in many cytochrome structures (8). Cysteine also contributes in mediating protein–DNA interactions such as occur with zinc fingers and ring fingers (9, 10). Among secondary structures, for each Sa level, the coil location is preferred by cysteine. Eighty percent of all neighbor sulfur atoms about cysteine occur in buried conditions, principally reflecting disulfide-bridges.

Small residues.

Gly and Ala, in addition to Leu, are the most abundant residues [Leu(9636), Ala(9546), Gly(9220)], of about equal numbers. Alanine is predominantly buried and favors a helical Ss state. When partly buried or at exposed Sa levels, Ala prefers the coil state. At all Sa levels, Gly is found prominently in coil locations as “fillers” or in sharp turn structural conformations. The (C) count per Ala = 5.6 and for Gly = 6.5. These yield C(Ala)/C(Gly) = 0.87, which verifies that Gly compared with Ala is more surrounded by (C) atoms. The corresponding ratios for (O) vs. (N) are 0.75 and 0.85, respectively, approximately the same as with the (C) density. ρ(Ala, SC) ranges for the SCs from 1.48 to 2.43. The (O) and (N) atom counts are highest in c-bu states. For all exposed conditions ρ(Gly, ex) ≥ 2.18.

Residue Atom Densities with Respect to (Backbone and Side-Chain) A-A Contacts.

The A-A neighbors consist of all backbone or side-chain residue atoms within 5 Å of backbone and side-chain atoms of the reference residue. Table 2 reports the (C), (O), (N), and total atom A-A counts and density values for each (aa, SC) of the protein structure data set.

Table 2.

Residue atom densities of all (backbone and side-chain) contacts

| SC | No. | C | O | N | ρ | T | No. | C | O | N | ρ | T | No. | C | O | N | ρ | T | No. | C | O | N | ρ | T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asp (8 backbone and side-chain atoms) | Glu (9) | Arg (11) | Lys (9) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| α-bu | 290 | 38.1 | 9.9 | 11.7 | 0.84 | 59.7 | 335 | 40.0 | 10.5 | 11.7 | 0.89 | 62.2 | 320 | 43.9 | 13.2 | 11.7 | 1.12 | 68.8 | 139 | 40.4 | 12.6 | 11.1 | 1.14 | 64.1 |

| β-bu | 264 | 36.3 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 0.97 | 56.7 | 206 | 38.2 | 10.5 | 10.7 | 0.97 | 59.3 | 227 | 43.2 | 13.5 | 10.9 | 1.23 | 67.6 | 113 | 38.9 | 11.9 | 9.4 | 1.26 | 60.2 |

| c-bu | 630 | 34.2 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 0.96 | 54.6 | 304 | 35.7 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 0.96 | 56.4 | 329 | 40.6 | 13.1 | 11.1 | 1.18 | 64.8 | 132 | 35.8 | 12.0 | 10.2 | 1.17 | 58.0 |

| α-pb | 403 | 30.9 | 8.4 | 10.2 | 0.82 | 49.4 | 750 | 32.1 | 8.6 | 10.0 | 0.85 | 50.7 | 810 | 35.7 | 11.3 | 9.8 | 1.14 | 56.8 | 608 | 32.5 | 10.2 | 8.9 | 1.14 | 51.4 |

| β-pb | 276 | 29.6 | 8.4 | 8.6 | 0.98 | 46.6 | 433 | 30.5 | 8.3 | 8.9 | 0.93 | 47.7 | 509 | 35.2 | 10.9 | 8.6 | 1.27 | 54.6 | 456 | 31.2 | 10.1 | 7.8 | 1.28 | 49.1 |

| c-pb | 1022 | 27.7 | 8.0 | 8.4 | 0.95 | 44.0 | 631 | 28.3 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 0.94 | 44.9 | 881 | 32.0 | 10.7 | 8.6 | 1.24 | 51.2 | 696 | 28.1 | 9.6 | 7.5 | 1.27 | 45.2 |

| α-ex | 997 | 23.5 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 0.87 | 37.9 | 1824 | 24.1 | 6.8 | 7.6 | 0.89 | 38.5 | 875 | 26.4 | 8.7 | 7.6 | 1.13 | 42.6 | 1526 | 24.0 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 1.11 | 39.2 |

| β-ex | 250 | 22.0 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 1.01 | 35.3 | 493 | 23.1 | 6.7 | 6.8 | 0.98 | 36.5 | 354 | 26.0 | 8.4 | 6.7 | 1.25 | 41.1 | 617 | 24.2 | 8.1 | 6.3 | 1.28 | 38.4 |

| c-ex | 2707 | 19.1 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 1.03 | 30.7 | 1982 | 18.9 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 1.03 | 30.5 | 1121 | 21.1 | 7.4 | 5.9 | 1.26 | 34.4 | 2407 | 19.3 | 7.0 | 5.5 | 1.28 | 31.8 |

| To | 6839 | 25.1 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 0.95 | 40.1 | 6958 | 25.9 | 7.4 | 7.9 | 0.93 | 41.1 | 5426 | 31.0 | 10.1 | 8.4 | 1.20 | 49.4 | 6694 | 24.8 | 8.4 | 6.9 | 1.22 | 40.1 |

| Leu (8) | Met (8) | Ile (8) | Val (7) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| α-bu | 2580 | 39.0 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 1.03 | 57.0 | 619 | 41.6 | 9.5 | 9.5 | 1.00 | 60.5 | 1363 | 38.9 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 1.03 | 57.0 | 1416 | 36.5 | 8.8 | 8.7 | 1.00 | 54.0 |

| β-bu | 1874 | 37.8 | 8.9 | 8.0 | 1.11 | 54.6 | 424 | 39.4 | 9.5 | 8.6 | 1.10 | 57.4 | 1859 | 37.2 | 8.9 | 7.9 | 1.13 | 53.9 | 2447 | 34.7 | 8.5 | 7.6 | 1.11 | 50.8 |

| c-bu | 1739 | 34.7 | 8.8 | 7.8 | 1.13 | 51.3 | 405 | 36.7 | 9.7 | 8.7 | 1.11 | 55.0 | 938 | 34.6 | 8.9 | 7.9 | 1.13 | 51.4 | 1185 | 31.7 | 8.5 | 7.6 | 1.12 | 47.8 |

| α-pb | 916 | 32.2 | 8.7 | 8.6 | 1.01 | 49.5 | 248 | 33.4 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 1.00 | 51.1 | 475 | 32.2 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 1.00 | 49.4 | 461 | 30.6 | 8.4 | 8.3 | 1.00 | 47.2 |

| β-pb | 440 | 30.3 | 8.3 | 7.5 | 1.10 | 46.0 | 101 | 32.0 | 8.8 | 7.9 | 1.10 | 48.7 | 429 | 29.9 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 1.11 | 45.6 | 602 | 27.9 | 7.9 | 7.2 | 1.09 | 42.9 |

| c-pb | 966 | 27.5 | 8.1 | 7.0 | 1.14 | 42.6 | 274 | 27.9 | 8.0 | 7.1 | 1.11 | 42.9 | 553 | 27.2 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 1.14 | 42.1 | 736 | 25.8 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 1.12 | 40.1 |

| α-ex | 359 | 24.6 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 0.99 | 39.4 | 88 | 25.2 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 1.00 | 39.8 | 168 | 24.4 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 0.99 | 39.3 | 269 | 23.8 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 0.98 | 38.2 |

| β-ex | 159 | 23.3 | 7.2 | 6.3 | 1.13 | 36.7 | 55 | 23.5 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 1.11 | 36.8 | 144 | 22.8 | 7.0 | 6.4 | 1.09 | 36.3 | 263 | 21.9 | 7.0 | 6.1 | 1.14 | 34.9 |

| c-ex | 603 | 19.1 | 6.4 | 5.4 | 1.17 | 30.8 | 217 | 17.7 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 1.11 | 28.3 | 381 | 19.0 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 1.13 | 30.4 | 645 | 18.2 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 1.13 | 29.4 |

| To | 9636 | 33.8 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 1.08 | 50.2 | 2431 | 34.5 | 8.8 | 8.3 | 1.06 | 51.5 | 6310 | 33.7 | 8.6 | 7.9 | 1.09 | 50.1 | 8024 | 30.9 | 8.1 | 7.5 | 1.08 | 46.5 |

| His (10) | Phe (11) | Trp (14) | Tyr (12) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| α-bu | 244 | 40.0 | 11.0 | 10.5 | 1.04 | 61.5 | 924 | 43.8 | 9.9 | 9.6 | 1.03 | 63.3 | 295 | 48.4 | 11.3 | 11.0 | 1.02 | 70.6 | 590 | 45.8 | 11.2 | 11.0 | 1.01 | 68.0 |

| β-bu | 246 | 38.9 | 10.9 | 9.9 | 1.10 | 59.7 | 1072 | 41.9 | 9.7 | 8.7 | 1.11 | 60.4 | 289 | 47.3 | 11.5 | 10.7 | 1.07 | 69.5 | 729 | 44.3 | 11.2 | 10.4 | 1.07 | 65.9 |

| c-bu | 341 | 36.0 | 10.6 | 9.5 | 1.11 | 56.0 | 918 | 39.7 | 9.8 | 8.8 | 1.11 | 58.2 | 358 | 43.2 | 11.3 | 10.2 | 1.10 | 64.7 | 609 | 41.3 | 11.1 | 10.4 | 1.07 | 62.7 |

| α-pb | 222 | 33.6 | 9.6 | 9.2 | 1.04 | 52.3 | 327 | 36.0 | 9.6 | 9.2 | 1.03 | 54.8 | 184 | 39.5 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 1.01 | 60.0 | 471 | 37.1 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 1.01 | 57.0 |

| β-pb | 218 | 32.5 | 9.4 | 8.2 | 1.14 | 50.1 | 297 | 33.9 | 9.2 | 8.1 | 1.13 | 51.3 | 170 | 38.0 | 10.2 | 9.4 | 1.08 | 57.5 | 506 | 35.8 | 9.9 | 9.1 | 1.08 | 54.8 |

| c-pb | 469 | 29.8 | 9.2 | 8.0 | 1.15 | 46.9 | 589 | 31.5 | 8.9 | 7.9 | 1.11 | 48.3 | 255 | 35.5 | 9.8 | 9.2 | 1.07 | 54.5 | 724 | 33.1 | 9.7 | 8.6 | 1.12 | 51.3 |

| α-ex | 190 | 24.7 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 1.02 | 39.8 | 116 | 26.1 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 0.99 | 41.5 | 39 | 27.1 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 1.02 | 43.0 | 154 | 26.9 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 1.03 | 42.6 |

| β-ex | 104 | 25.3 | 8.1 | 6.5 | 1.24 | 39.8 | 104 | 24.5 | 7.2 | 6.5 | 1.10 | 38.2 | 30 | 27.4 | 7.7 | 7.5 | 1.02 | 42.5 | 132 | 25.9 | 7.8 | 7.1 | 1.09 | 40.8 |

| c-ex | 538 | 19.3 | 6.5 | 5.4 | 1.20 | 31.2 | 325 | 20.6 | 6.5 | 5.7 | 1.13 | 32.7 | 107 | 22.9 | 7.2 | 6.1 | 1.16 | 36.2 | 369 | 22.0 | 7.1 | 6.2 | 1.14 | 35.3 |

| To | 2572 | 30.3 | 9.0 | 8.1 | 1.11 | 47.4 | 4672 | 37.4 | 9.3 | 8.5 | 1.09 | 55.2 | 1727 | 40.9 | 10.5 | 9.8 | 1.06 | 61.2 | 4284 | 37.3 | 10.1 | 9.4 | 1.07 | 56.7 |

| Ser (6) | Thr (7) | Asn (8) | Gln (9) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| α-bu | 597 | 34.5 | 9.3 | 9.2 | 1.00 | 53.0 | 628 | 36.0 | 9.5 | 9.3 | 1.01 | 54.8 | 259 | 38.6 | 10.7 | 10.6 | 1.01 | 59.8 | 276 | 41.2 | 11.1 | 11.0 | 1.01 | 63.2 |

| β-bu | 657 | 32.2 | 9.3 | 8.5 | 1.09 | 50.0 | 768 | 33.9 | 9.3 | 8.6 | 1.07 | 51.8 | 271 | 36.4 | 10.7 | 9.8 | 1.09 | 56.8 | 207 | 39.5 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 1.04 | 60.5 |

| c-bu | 1069 | 30.1 | 9.2 | 8.4 | 1.09 | 47.7 | 974 | 31.6 | 9.3 | 8.3 | 1.11 | 49.1 | 610 | 34.9 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 1.08 | 54.8 | 250 | 37.3 | 10.9 | 9.9 | 1.10 | 58.1 |

| α-pb | 341 | 28.5 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 0.99 | 45.1 | 367 | 29.7 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 1.00 | 46.6 | 360 | 32.3 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 1.00 | 51.1 | 477 | 33.9 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 0.99 | 53.3 |

| β-pb | 377 | 26.0 | 8.0 | 7.2 | 1.10 | 41.2 | 590 | 27.5 | 8.2 | 7.5 | 1.10 | 43.2 | 227 | 30.6 | 9.2 | 8.3 | 1.10 | 48.0 | 261 | 32.1 | 9.4 | 8.5 | 1.10 | 50.0 |

| c-pb | 984 | 24.5 | 7.7 | 6.9 | 1.11 | 39.1 | 841 | 25.9 | 8.0 | 7.2 | 1.11 | 41.0 | 808 | 28.5 | 8.9 | 7.9 | 1.12 | 45.3 | 476 | 29.7 | 9.1 | 8.3 | 1.09 | 47.0 |

| α-ex | 672 | 21.6 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 1.01 | 35.3 | 520 | 23.3 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 0.99 | 37.8 | 598 | 23.7 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 0.98 | 38.6 | 881 | 24.8 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 1.01 | 40.1 |

| β-ex | 326 | 20.4 | 6.6 | 5.8 | 1.13 | 32.7 | 538 | 21.8 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 1.11 | 34.8 | 245 | 22.9 | 7.4 | 6.4 | 1.14 | 36.7 | 280 | 23.1 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 1.10 | 36.7 |

| c-ex | 2178 | 17.2 | 6.0 | 5.0 | 1.19 | 28.2 | 1706 | 18.5 | 6.2 | 5.3 | 1.15 | 30.0 | 2117 | 19.1 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 1.16 | 31.1 | 1185 | 19.5 | 6.5 | 5.7 | 1.14 | 31.6 |

| To | 7201 | 24.5 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 1.09 | 39.0 | 6932 | 26.5 | 7.9 | 7.3 | 1.08 | 41.6 | 5495 | 26.0 | 8.1 | 7.4 | 1.09 | 41.5 | 4293 | 27.7 | 8.4 | 7.8 | 1.06 | 43.9 |

See legend of Table 1. Supplemental material is available on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org.

Charge residues.

The total neighbor atom count about Asp is greatest in the c-ex state (30%), secondly in the c-pb state (16.4%), and next in the α-ex state (13.8%). This ordering applies as well for the separate (O), (N), and (C) atom types. The C(Asp) is highest in the α-bu state (38.1) with lowest value 19.1 in the c-ex state. Notably, C(Asp), for each Ss state, decreases from bu to pb to ex, and for each Sa level decreases from α to β to coil. The (O) and (N) average counts also decrease relative to Sa levels but are less variable relative to Ss states. This may suggest that (C) packing is less important than hydrogen bond associations. The O(Asp) density is about the same for all Sa levels, independent of Ss, whereas C(Asp) is more variable. N(Asp) is highest in the α state at each Sa level. The ρ contrasts of O(Asp) vs. N(Asp) occur in the α state preferring (N) to (O) atom neighbors but not as strongly as in S-S contacts. These interactions pertain to salt bridges and hydrogen bonds. Affinity in β and coil states for (O) and (N) atom neighbors are about equal. This may signify a more polar environment in the α than in the β conformation. Glu versus Asp entails variant total atom neighbor counts. In particular, Tot(Glu) is highest, 24%, in the α-ex state, secondly 21.2% in a c-ex state, and 13% in the α-pb state. The same ordering is maintained for Ccum(Glu), Ocum(Glu), and Ncum(Glu) neighbor atom counts. The density distribution C(Glu) parallels that of C(Asp). The affinity for (O) versus (N) atoms (ρ values) are largely concordant between Glu and Asp.

The aggregate atom neighbors of Arg residues is greatest in the α-pb and c-pb states and smallest in the β-ex state (5%). All ρ values exceed 1, confirming an excess of (O) over (N) neighbors in all SCs with the sharpest contrasts for coil and β states and the least variation for the α state. The smallest total neighbor atom counts of Lys are 2–3% under buried conditions. In assessments of total atom counts, the backbone influences are paramount, and ρ(Lys, SC) ≈ ρ(Arg, SC). For each SC, the normalized densities satisfy C*(Lys) > C*(Arg), and the same inequalities apply for (O) and (N) normalized densities.

His.

Total atom neighbors about His involve 18% in c-pb states, 16% in c-bu states, and 14% in the c-ex states. For all SCs of α states, ρ values are barely above 1, in the range (1.02–1.04) and for the coil and β states in the range (1.10–1.24). His residues confer stability in α-helices primarily at the C-cap, where they may compensate the helix dipole and H-bond to free carbonyl groups (11).

Aliphatics.

The average and normalized counts for all atom types decrease, with each Sa level, in the order α to β to coil states. Globally, the Met environments are marginally more dense than those of Ile, with total average counts of 6.43 and 6.26, respectively. The side-chain branching of Ile possibly curtails a tight packing, consistent with the observation that the difference between Met and Ile is pronounced in the buried state. The key factor demarcating Met from Ile pertains to (C) atom neighbors because both (O) and (N) atoms possess similar densities. For all SCs, we have Tot*(Val) > Tot*(Met) > Tot*(Leu) > Tot*(Ile), and the same ordering for C*, N*, and O*. For aliphatics, the contrasts in (O) and (N) densities marginally favor (O), revealed by ρ values in the range 0.98 to 1.17. Invariably ρ(aliphatics, α) ≈ 0.98–1.03 whereas ρ(aliphatics, β or coil) ≈ 1.09–1.17.

Aromatics.

The atom densities per amino acid are Tot(Phe) = 55.2, Tot(Tyr) = 56.7, Tot(Trp) = 61.2, highest for tryptophan but when normalized by the residue atom numbers (Phe = 11, Tyr = 12, Trp = 14) yield 5.01, 4.37, and 4.73, respectively. Thus, when normalized by “size,” Phe entails the greatest aromatic density of neighboring atoms and Trp the least. However, for every SC, we find O*(Tyr) > O*(Phe) > O*(Trp), N*(Tyr) > N*(Phe) > N*(Trp). By contrast, normalized inequalities for carbon are reversed between Phe and Tyr, C*(Phe) = 3.39 > C*(Tyr) = 3.10 > C*(Trp) = 2.91. This could be expected because Phe is predominantly hydrophobic whereas Tyr and Trp possess roughly equal capacities for hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions. The ρ values among all aromatics range from 0.99 to 1.16, indicating a modest preference for (O) atoms more than for (N) atoms. The largest ρ values occur in the c-ex state of 1.13–1.16.

Small hydroxyls.

For each SC, C*(Ser) > C*(Thr), O*(Ser) > O*(Thr), N*(Ser) > N*(Thr). ρ(Ser) in α states attract (O) and (N) atoms about equally (ρ ≈ 1), but in β and coil states ρ(Ser) values attain the levels (1.09–1.19). ρ(Thr) values parallel that of ρ(Ser). Ser and Thr are versatile in hydrogen bonding to backbone groups, side-chains, or solvent. Ser and Thr significantly attract His and Asp (6). In particular, Ser (more than Thr) associates with His as either a proton acceptor or donor and are often together at active sites such as in serine and metallo proteases. Ser and Asp prefer turns, loops, or amino ends of α-helices. Glu and His are often together at the carboxyl helix cap because of their hydrogen bonding capacity and because of a favorable interaction with the helix dipole (11).

Amides.

The (O) to (N) density contrasts have ρ(Asn,α) ≈ 0.98–1.00 whereas ρ(Asn, β or coil) ≈ 1.08–1.16 and generally for each Sa level ρ(Asn, coil) ≈ ρ(Asn, β). The analysis of the atom densities about Gln paraphrases that of Asn.

Cys.

The bulk (79%) of neighboring atoms about Cys are in a buried state and favoring a coil Ss. This arrangement applies also for (C), (O), and (N) atoms. Cys in β and coil states favor (O) to (N) neighbors but in an α state is equally disposed to (N) and (O) neighbors.

Small residues.

The total atom neighbor count of Ala is highest when Ala is in an α-bu state (28%) and second in the c-bu state (16%). The distribution of (C), (O), and (N) atom neighbors keep to the same order. The total count about Gly is highest when Gly is in the c-ex state (29%) and next in the c-bu state (16%).

Discussion

The text provides results and highlights contrasts on (C), (O), and (N) atom densities about natural groups of amino acids. The different atom densities are determined with respect to side-chain interactions over a 5Å neighborhood (labeled S-S) and with respect to all atom (side-chain and backbone) interactions (labeled A-A). For each amino acid, we have determined the S-S ρ(aa, SC) = O(aa, SC)/N(aa, SC) values and the corresponding A-A values. The lowest and highest S-S ρ values are realized for anionic (ρ significantly low, 0.77–0.85) and cationic (ρ significantly high, 2.4–3.0) residues, respectively. Aliphatic and aromatic residues are surrounded by (O) atoms more than (N) atoms, ρ ≈ 1.1–2.0, and uncharged polar residues have ρ in the range (1.5–2.8). The A-A ratios are closer to 1, resulting mainly from equal numbers of (O) and (N) atoms contributed from backbone sources. For the A-A density the ρ values are, for most amino acids, lowest in the α-bu state. The c-ex state tends to have the highest ρ value.

For S-S total contacts, all ρ values exceed 1, indicating that proteins structures have more (O) than (N) atoms distributed in 5Å environments for every SC averaged across all amino acid types. However, for most residue S-S total contacts, the ρ assessments in the α state as against the β and coil states show significantly lower values. The total counts of side-chain (O) atoms to (N) atoms contained in the protein structure set is 148,469 to 99,243, respectively. Thus, the global ratio O/N ≈ 1.5 is higher than the global average ρ = 1.29. For S-S interactions, ρ attains its highest values at surface (exposed) locations, especially in the β and coil states having ρ = 1.84 and ρ = 1.79, respectively. Under A-A total atom contacts, the ρ values for α states are significantly reduced, generally 1.00–1.02, emphasizing on average equal numbers of (O) and (N) neighbor atoms whereas ρ assessments for β and coil states are elevated to the range 1.10–1.15.

To help interpret these ρ ratios, we calculated the global average (O) and (N) contents in the representative protein structure set. The theoretical numbers of (O) to (N) side-chain atoms among amino acids have the equality 9 to 9: (2O in Asp, 2O in Glu, 1O in Tyr, 1O in Ser, 1O in Thr, 1O in Asn, 1O in Gln) to (3N in Arg, 1N in Lys, 2N in His, 1N of Trp, 1N of Asn, 1N of Gln). However, in surveying the amino acid composition in our data set, the side-chain of an average residue contains 0.48 (O) atoms and 0.34 (N) atoms, producing an average side-chain ratio (O)/(N) = 1.4. Thus, the protein side-chain environment is more (O) than (N), consistent with the observed ρ values exceeding 1 (exception acidic residues). If backbone atoms are incorporated in this calculation, the average residue of the data set contributes 1.48 (O) atoms and 1.34 (N) atoms, yielding (O)/(N) = 1.1. Among side-chain interactions, most aliphatics possess ρ values above 1 but below 1.4.

Living cells tend to be acidic because of phosphate heads on membrane surfaces and the intrinsic acidic backbone of RNA, DNA, and ATP molecules (12). Moreover, the majority of species proteins favor a net negative charge (13). Residues on the protein surface presumably need to be selective to be able to interact with appropriate structures and avoid interacting with other structures. In this context, the protein net negative charge mediated by electrostatic repulsion helps to avoid undesirable interactions with DNA, RNA, membrane surfaces, and certain other proteins. The extracellular milieu for metazoans is slightly alkaline, with pH ≈ 7.2–7.4 (14), whereas the intracellular pH is variable ranging from 5.0 to 7.2, depending on tissue type and subcellular localizations (15). It is considered that enzyme activity is “optimum” at a pH similar to the pH of host cells, which in mammalian organisms tend to favor acidic conditions. Also, the protein negative charge tendency can contribute in modulating secretion and intracellular transport, in inducing transcriptional activation and in mediating rapid and potent interactions of protein assemblages.

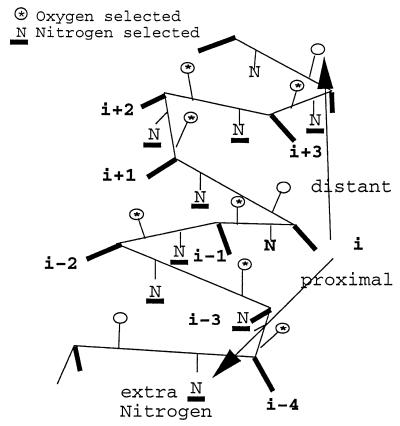

For the A-A contacts, the α state, independent of the Sa level, registers the lowest ρ value hovering about 1. Reasons for this phenomenon are unclear. However, the following thoughts may be relevant. In the central part of a helix, the backbone 5-Å neighbor (N) and (O) counts generally equal 7. Indeed, there are three (O) and three (N) backbone atoms contributed from the primary sequence residues (i–3, i–2, i–1) and a fourth backbone (O) from residue i–4 within 5Å distance of the ith reference residue (Fig. 1). Similarly, the residues (i + 1, i + 2, i + 3) contribute three (O) and three (N) backbone atoms and a fourth backbone (N) from residue i + 4 within 5 Å of the reference residue i. However, because of the natural tilt of the residue side-chains, in the core part of the α-helix, directed backwards (16), an additional backbone (N) from residue i–4 pointing downwards from the reference residue could be included in the 5Å neighborhood of the side-chain of the reference residue (Fig. 1). On the other hand, the backbone (O) of the i + 4 residue and the side-chain of the reference residue are effectively oppositely directed and therefore unlikely to be within 5Å distance. Thus, the side-chain orientation would allow for an extra (N) in the 5Å neighborhood and could augment the count of (N) backbone atoms to eight whereas the count of (O) backbone atoms is seven, yielding a diminished ρ value for the α state in the A-A contacts.

Figure 1.

In this figure, the Cα trace of an α-helix is represented (light) with residue side-chains (heavy). Carbonyl groups are designated by a circle, and amino groups are designated by the letter “N.” Backbone oxygen or nitrogen atoms within 5 Å of the reference residue i are tagged with an asterisk or are underlined, respectively. Generally, there is an equal number of oxygen and nitrogen backbone atom neighbors, but, in the A-A contact mode, the residue side-chain backward tilt can allow an extra backbone nitrogen from residue i–4 within 5 Å of the reference residue (see text). Note that carbonyl oxygen atoms have the direction of the α-helix whereas nitrogen atoms have the opposite direction.

The nature of the carboxyl and amino terminal and neighboring loop residues in α helices may contribute somewhat to the reduced ρ values in α-helices. Near the N-cap, Gly, Ser, Asn, Asp, and Glu are prominent and, near the C-cap, Lys, Arg Asn, Gln, and His are prominent. From this perspective, the aggregate (N) atoms about these caps and loops tend to be selected more than that of (O) atoms. Another consideration takes account of the general propensities among amino acids favoring central parts of α-helices versus β-sheets. The 10 best residue assignments to α-helices (17) in decreasing order of preference consist of Glu, Ala, Leu, His, Met, Gln, Trp, Val, Lys containing an aggregate 5N and 3O in their side-chains whereas the 10 preferred residue assignments to β sheets in decreasing order are Met, Val, Ile, Cys, Tyr, Phe, Gln, Leu, Thr, Trp of aggregate 3O and 2N. These theoretical counts of (N) to (O) have the ratio (5/3) for side-chains of α-helical residues compared with (2/3) for β-strand residues.

Because α helical conformations tend to be more compact structurally than β strand and coil conformations, we would expect to encompass more (C) atoms about α helices than about β strands and about coils for a 5-Å neighborhood of most residues. On this basis generally, for all amino acids and A-A contacts, the α state carries the highest average (C) counts and total atom counts. Corresponding assessments for S-S contacts are mainly independent of the Ss state. As expected, the S-S carbon C(SC) values are highest under buried conditions (≈14) for all Ss states, reduced to ≈10 under partly buried conditions, and further reduced to ≈5 under exposed conditions. With respect to side-chain contacts, the O(SC) counts per 5Å neighborhood averaged over all amino acids range from 1.02 to 1.64 (global average 1.29) compared with N(SC) generally below 1 (global average 0.86). At partly buried locations, N(SC) values range from 1.03 to 1.13.

We emphasized earlier that, except for acidic amino acids, ρ, for all SC, is >1. Why do ρ values averaged over amino acids achieve their highest levels under exposed (surface) conditions; i.e., why are there significantly more (O) than (N) atoms at protein surface environments than in buried or in partly buried protein regions? We suggest that it may be advantageous at the protein surface to emphasize acidic residue side-chains for at least two reasons. First, a negative charge protein surface can help avoid undesirable nonspecific interactions with the negatively charged phosphate groups of DNA, RNA, ATP, and the inner membrane phosphate heads. Second, an (O) predominance about the surface makes the surface more hydrophilic and less likely to form insoluble proteins (for measurements, see ref. 18, p. 334). These characteristics would likely not apply to proteins of special function such as membrane proteins. Solvent occupies cavities in proteins and, via H-bonding networks, plays a major role in helping to orient and stabilize protein conformation; solvent can serve as a transient surrogate for substrate; solvent can help in coordinating metals especially calcium and zinc; and entropic effects of solvent exclusion contribute in establishing quartenary structures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. R. Altman, Dr. L. Brocchieri, and Dr. E. Blaisdell for valuable comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants 5R01GM10452-34 and 5R01HG00335-11.

Abbreviations

- SC

structural category

- Sa level

solvent accessibility level

- Ss state

secondary structure state

- bu

buried

- pb

partly buried

- ex

exposed

References

- 1.Baud F, Karlin S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12494–12499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanks S K, Quinn A M. Methods Enzymol. 1991;200:38–63. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)00126-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose G D, Geselowitz A R, Lesser G J, Lee R H, Zefhus M H. Science. 1985;229:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.4023714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Z Y, Karlin S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8350–8355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adman E T. Adv Protein Chem. 1991;42:147–197. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60536-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karlin S, Zuker M, Brocchieri L. J Mol Biol. 1994;239:227–258. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizuno T. J Biochem. 1998;123:555–563. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tervoort M J, Van Gelder B F. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;722:137–143. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(83)90166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg J M. Annu Rev Biophys Chem. 1990;19:405–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.19.060190.002201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saurin A J, Borden K L, Boddy M N, Freemont P S. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;6:208–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klingler T M, Brutlag D L. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1847–1857. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brocchieri L, Karlin S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;26:12136–13140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karlin S, Blaisdell B E, Bucher P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;5:729–738. doi: 10.1093/protein/5.8.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roos S, Boron W F. Physiol Rev. 1981;61:296–434. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1981.61.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stryer L. Biochemistry. New York: Freeman; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Branden C, Tooze J. Introduction to Protein Structures. New York: Garland; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prevelige J R, Fasman G D. In: Prediction of Protein Structure and the Principles of Protein Conformation. Fasman G D, editor. New York: Plenum; 1989. pp. 391–416. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pauling L. The Nature of the Chemical Bond. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press; 1940. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.