Abstract

A protease-resistant core domain of the neuronal SNARE complex consists of an α-helical bundle similar to the proposed fusogenic core of viral fusion proteins [Skehel, J. J. & Wiley, D. C. (1998) Cell 95, 871–874]. We find that the isolated core of a SNARE complex efficiently fuses artificial bilayers and does so faster than full length SNAREs. Unexpectedly, a dramatic increase in speed results from removal of the N-terminal domain of the t-SNARE syntaxin, which does not affect the rate of assembly of v-t SNARES. In the absence of this negative regulatory domain, the half-time for fusion of an entire population of lipid vesicles by isolated SNARE cores (≈10 min) is compatible with the kinetics of fusion in many cell types.

Many genetic and biochemical experiments have implicated SNAREs in the overall process of membrane fusion (1–6). The finding that isolated SNARE proteins can efficiently fuse lipid bilayers directly establishes that they are the basic machinery that merges membranes (7), a conclusion recently confirmed in an elegant study using permeabilized cells (8) and by the demonstration of contents mixing during SNARE-dependent fusion [see the accompanying paper by Nickel et al. (9)]. This principle is underscored by the internal architecture of the SNARE complex, whose “core” consists of four parallel α-helices packed into a single bundle with their membrane anchors emerging together from one end of the assembled SNARE complex (10–14).

The structure of the cytoplasmic core domain of a SNARE complex is reminiscent of the structure of the extracellularly localized core region of many viral fusion proteins in what is thought to correspond to a postfusogenic conformation (15, 16). This suggests a general principle for membrane fusion, in which pin-like structures bridging two membranes promote their fusion. However, no core complex, whether cellular or viral, has actually been shown to be fusogenic. Here, we report such evidence with a core domain of SNARE proteins.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Construction, Protein Expression, and Purification.

The following v-SNARE and t-SNARE complexes were bacterially expressed and purified by nickel affinity chromatography: VAMP2His6; syntaxin1/His6SNAP-25 (SYN/SNAP-25); thrombin-cleavable syntaxin1/His6SNAP-25 (tcSYN/SNAP-25); syntaxin1/thrombin-cleavableHis6SNAP-25 (SYN/tcSNAP-25); and thrombin-cleavable syntaxin1/thrombin-cleavableHis6SNAP-25 (tcSYN/tcSNAP-25). For detailed information, see the supplemental material on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org.

Protein Reconstitution into Liposomes and Thrombin Cleavage of t-SNARE Liposomes.

Both VAMP2 and t-SNARE complexes were reconstituted into liposomes as described (7). Once proteoliposomes were harvested, tcSYN/SNAP-25 liposomes were first treated with human thrombin (Sigma, catalogue number T-1063) at 0.02 units/μl for 2 hours at room temperature and subsequently were inhibited with 2 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride (Calbiochem). SYN/tcSNAP-25, tcSYN/tcSNAP-25, or SYN/SNAP-25 containing proteoliposomes were treated with 0.04 units/μl thrombin (Sigma) for 4 hours at 37°C and subsequently were inhibited with 2 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride. As a control, thrombin was preinactivated by first treating thrombin with 2 mM 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride before addition to t-SNARE liposomes. To access the lumenally oriented t-SNAREs, t-SNARE liposomes were lysed with 0.2% TX-100. Thrombin cleavage products were electrophoresed by SDS/PAGE using NOVEX 10% Bis-Tris gels (NOVEX, San Diego), and proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue staining. We did observe doublet bands for SYN HABC and SNAP-25 HA, which have likely been differentially proteolysed at the C terminus.

Conversion of Percent of 7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole (NBD) Fluorescence to Rounds of Fusion.

To obtain a calibration curve that would allow us to convert NBD fluorescence as percent of maximum into rounds of fusion of donor vesicles, a series of vesicle preparations with different ratios of donor to acceptor lipid was made. The donor lipid and acceptor lipid mixes are as previously described (7). Donor and acceptor lipid mixtures were premixed in 1:0, 1:0.5, 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, and 1:8 ratios, and 0.3 μmol of total phospholipid were dried as described (7). One-hundred microliters of purified vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 (VAMP2) in 1% N-octyl glucoside (Boehringer Mannheim) was reconstituted by using each of the prediluted lipid mixes, and liposomes were isolated and recovered as described (7). After correcting for lipid recovery, we measured the NBD fluorescence of the same total amount of “fluorescent” lipid for each dilution, i.e., 1:0 dilution (5 μl), 1:0.5 dilution (7.5 μl), 1:1 dilution (10 μl), 1:2 dilution (15 μl), 1:4 dilution (20 μl), and 1:8 dilution (40 μl) before and after detergent addition [0.5% (wt/vol) N-dodecylmaltoside (Boehringer Mannheim) final concentration]. The value of the undiluted sample (1:0 donor:acceptor lipid before detergent addition) was subtracted from all data points, and the percent of NBD fluorescence was calculated as the ratio before and after detergent addition. The percent of maximum NBD fluorescence was plotted versus fold lipid dilution, representing rounds of fusion assuming same size v-liposomes and t-liposomes. Inversion of the axis and using a double exponential fitting procedure yielded the following equation to allow the conversion of percent of maximum NBD fluorescence into rounds of fusion: Y = (0.49666*e(0.036031*X)) − (0.50597*e(−0.053946*X)), where Y is rounds of fusion and X is percent maximum NBD fluorescence for any given time point of the kinetic measurement.

Fusion Assays.

Fusion assays were performed as described (7) except that 10 μl of 2.5% (wt/vol) dodecylmaltoside instead of TX-100 was added at the end of the fusion reaction to minimize quenching. Conversion to percent of maximum NBD fluorescence was performed as described (7).

Results

Calibration of Fusion Measurements.

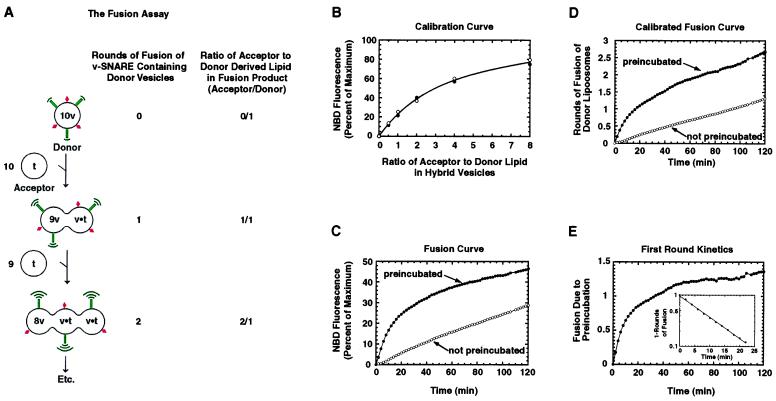

We have previously shown (7) that v- and t-SNAREs reconstituted into separate populations of synthetic bilayer vesicles promote vesicle fusion as measured by a lipid mixing assay (17). Our application of this assay makes use of two fluorescent lipids, NBD–1,2-dipalmitoyl phosphatidyl- ethanolamine (PE) and rhodamine-PE, both initially present in VAMP (v-SNARE-containing) “donor” vesicles. Fluorescent lipids are not included in the preparation of the syntaxin/SNAP-25 (t-SNARE-containing) “acceptor” vesicle population (Fig. 1A). Upon excitation of NBD, energy will be transferred to the rhodamine fluorophore in a process known as fluorescence resonance energy transfer, which is strongly dependent on the distance between the two fluorophores. Therefore, the dilution of the NBD-PE and rhodamine-PE mixture with nonfluorescent lipids when donor and acceptor vesicles fuse results in an increase in NBD fluorescence.

Figure 1.

Calibration of the fusion assay. (A) Schematic representation of SNARE-dependent liposome fusion reaction. Donor liposomes (v) contain an equimolar amount of NBD-PE (green beacons) and rhodamine-PE (red diamonds) and include the v-SNARE VAMP2. Each round of fusion decreases the concentration of fluorescent phospholipid in the bilayer, decreasing quenching of NBD (green beacons) and increasing the NBD fluorescence. (B) Calibration of percent of NBD fluorescence to rounds of fusion. Various lipid mixtures were prepared from the fluorescent donor lipids mix (used to prepare donor liposomes) and the nonfluorescent acceptor lipids mix in the following proportions (acceptor:donor): 0:1, 0.5:1, 1:1, 2:1, 4:1, and 8:1, mimicking the result (as shown in A) of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 rounds of fusion of donor vesicles, respectively. These lipid mixtures were used to reconstitute VAMP2 into liposomes, and the NBD fluorescence in each set of re-isolated liposomes was expressed as a percent of the maximum fluorescence. The closed and open circles represent two independent experiments. (C) Normalized NBD fluorescence versus time of incubation. Shown is a standard fusion reaction (as described in A) measuring the increase in NBD fluorescence in which liposomes were either mixed and preincubated overnight a 4°C (closed circles), thereby allowing SNARE complexes to form before fusion at 37°C, or were not preincubated (open circles). (D) The same data as in C, now expressed as rounds of fusion of donor vesicles according to the calibration curve in B. (E) Consumption of predocked vesicles. The rounds of fusion of nonpredocked vesicles were subtracted from the rounds of fusion obtained from experiments in which predocked vesicles were used, and this difference was plotted versus time. To examine whether consumption of the predocked population behaved like a first order reaction, we represented the substrate of this reaction as 1 − [rounds of fusion (for the first round)] versus time (Inset).

Each donor vesicle has ≈10× the copies of v-SNAREs as compared with copies of t-SNAREs in acceptor vesicles. To have an equal number of v- and t-SNARE proteins in each fusion reaction, we add ≈10 acceptor (t-SNARE) vesicles for each fluorescent donor (v-SNARE) vesicle. Therefore, when one v-SNARE containing vesicle fuses with one t-SNARE containing vesicle, the concentration of fluorescent lipid is reduced by about half, and all of the t-SNAREs in the new vesicle will likely be complexed by an equal number of v-SNAREs (Fig. 1A). About 90% of the v-SNAREs in the new vesicle will still be free to partner t-SNAREs in other acceptor vesicles (Fig. 1A), so phospholipids (including NBD and rhodamine PE) initially present in donor vesicles can participate in multiple rounds of fusion. With each round of fusion, NBD-PE and rhodamine-PE will be a progressively smaller fraction of total phospholipid in the fusion products, resulting in a progressive increase in NBD fluorescence as fluorescence resonance energy transfer decreases (Fig. 1A).

Previously, we presented the results of fusion experiments as a percentage of maximum NBD fluorescence (7). To calibrate the fluorescence measurement in terms of rounds of fusion of donor vesicle phospholipids, we mimicked the lipid composition expected of vesicle products (Fig. 1A) before fusion (“zero rounds”) and after one round, two rounds, and so on. This was accomplished simply by mixing the NBD and rhodamine-containing lipids (used to form donor vesicles) with the nonfluorescent lipids (used to make acceptor vesicles) in a series of ratios of acceptor to donor lipids. Vesicles were then formed as described for proteoliposomes used in fusion experiments. The resulting NBD fluorescence then was determined as a function of the ratio of acceptor to donor lipids in the hybrid vesicles and converted into a calibration curve (Fig. 1B; see Materials and Methods).

v- and t-SNARE-containing liposomes either were preincubated for ≈16 hours at 4°C [a condition that permits SNARE complex formation but not fusion (7)] or were not preincubated before fusion at 37°C. The increase in NBD fluorescence as a function of time at 37°C (Fig. 1C) was converted to rounds of fusion of donor vesicles according to the calibration curve (Fig. 1B), resulting in a calibrated representation of rounds of fusion vs. time (Fig. 1D). Without preincubation (Fig. 1D, open circles), fusion products appear linearly with time for at least 2 hours, resulting in a total of 1.5 rounds of fusion during that period. When liposomes were first preincubated at 4°C to allow docking via SNARE complexes (7) between v- and t- liposomes (Fig. 1D, closed circles), about three rounds of fusion occurred in the same period.

Kinetic Dissection of Docking and Fusion Steps.

In principle, the overall rate of fusion is determined by two processes: (i) the rate of “functional” docking (i.e., assembly of fusion-competent SNARE complexes between liposomes) and (ii) the rate of fusion once fusion-competent SNARE complexes have assembled. Liposomes that were not preincubated fuse linearly at a rate corresponding to a half-time for the first round of fusion of ≈40 min (Fig. 1D, open circles), representing the time required for half of all of the donor vesicles to complete the overall process of fusion once. As a result of the 4°C preincubation, the kinetics are now biphasic (Fig. 1D, closed circles).

The difference between the fusion curves for preincubated and nonpreincubated samples measures the transient kinetic advantage provided by the preincubation (Fig. 1E). This kinetic advantage should result from consumption of donor and acceptor vesicles that had functionally docked during the preincubation and, after transfer to 37°C, fuse more rapidly than undocked vesicles. This population fuses with approximately first order exponential kinetics, and the first half round of fusion now occurs within ≈7 min (Fig. 1E Inset). The kinetic advantage attributable to preincubation is seen as a clear breakpoint in Fig. 1D at ≈15 min (closed circles) at about one round of fusion.

Removal of Syntaxin’s N-terminal Domain Enhances Fusion.

A protease-resistant core of the neuronal SNARE complex has been identified (18, 19) and consists of the syntaxin H3 domain (H3 = helix, amino acids 191–260), almost the entire VAMP molecule (amino acids 1–91), and two helical regions from SNAP-25: HA (amino acids 1–94) and HB (amino acids 125–206). Two regions not present are (i) the N-terminal HABC–hinge domain of syntaxin and (ii) the loop region joining the two SNAP-25 helices.

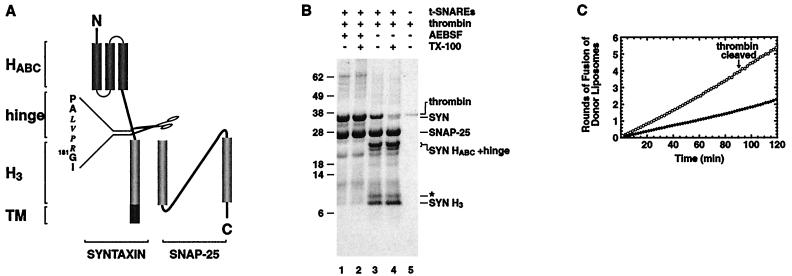

We first tested whether the HABC domain (20) or the hinge region of syntaxin is necessary for fusion activity. To do this, a thrombin cleavage site was introduced at the junction of the hinge domain and the syntaxin H3 domain that contributes to the core helical bundle of the SNARE complex (Fig. 2A). This thrombin-cleavable syntaxin (tcSYN) was co-expressed and co-purified as a complex with SNAP-25 and then was reconstituted into synthetic liposomes. After reconstitution, thrombin was added to remove the syntaxin HABC domain and the hinge region from the syntaxin H3 domain, resulting in a t-SNARE with a truncated syntaxin whose N-terminal residue now corresponds to residue 181 of full-length syntaxin (Fig. 2B, lane 3). As expected, two new bands appear after thrombin digestion, one corresponding to the HABC+hinge segment (SYN HABC+hinge) and the other representing the membrane-attached syntaxin H3 domain (SYN H3). The remaining unaltered tcSYN (Fig. 2B, lane 3) is attributable to lumenally oriented copies, as shown by the fact that they become accessible to thrombin upon addition of TX-100 (Fig. 2B, lane 4).

Figure 2.

Removal of the syntaxin HABC+hinge domain increases the rate of SNARE mediated liposome fusion. (A) Schematic representation of the membrane distal three-helical bundle formed by HABC domain (20), the hinge domain, the membrane proximal H3 helix of syntaxin, and the helical and loop domains of SNAP-25. A thrombin site was engineered into syntaxin by replacing amino acids 176–180 (IFAS) with the thrombin recognition sequence (LVPR). (B) Coomassie blue-stained protein profile of tcSYN/SNAP-25 before and after thrombin treatment. After reconstitution, proteoliposomes containing thrombin-cleavable syntaxin/SNAP-25 were treated with either inactive thrombin (lanes 1 and 2) or active thrombin (lanes 3 and 4). This proteolysis resulted in the separation of the syntaxin HABC+hinge domain and the H3 helix (lanes 3 and 4). An aliquot of tcSYN/SNAP-25 liposomes was treated with inactive thrombin (lane 2) and active thrombin (lane 4) in the presence of 0.2% TX-100 to access the lumenally oriented tcSYN/SNAP-25 complex. Thrombin was electrophoresed separately because it comigrates with syntaxin (lane 5). The asterisk (*) indicates a minor SNAP-25 cleavage product. AEBSF, 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride. (C) Kinetic profile of membrane fusion of tcSYN/SNAP-25 and SYN H3/SNAP-25 liposomes with v-liposomes. Donor liposomes containing VAMP were mixed with full length (closed circles) or SYN H3/SNAP-25 (open circles) liposomes, and the increase in NBD fluorescence at 37°C was monitored for 2 hours. This increase in NBD fluorescence then was converted to rounds of fusion.

Cleaved (SYN H3/SNAP-25) or uncleaved (tcSYN/SNAP-25) t-SNARE liposomes (as control) were mixed with v-SNARE liposomes and were allowed to fuse for 2 hours at 37°C (without any preincubation). The uncleaved tcSYN/SNAP-25 liposomes fuse with kinetics similar to their wild-type counterpart (compare Fig. 2C, closed circles, with Fig. 1D, open circles). Remarkably, SYN H3/SNAP-25 liposomes are able to fuse at a much higher rate than their full length counterpart, resulting in a dramatic increase in the number of rounds of fusion over a 2-hour period (Fig. 2C, open circles). The half-time for the first round of fusion is ≈10 min for SYN H3/SNAP-25 liposomes (averaged over a 2-hour period).

Control experiments demonstrate that neither the tcSYN/SNAP-25 nor the thrombin-cleaved SYN H3/SNAP-25 liposomes fused with protein-free liposomes (data not shown). Moreover, neither t-SNARE liposome fused with VAMP2 liposomes in the presence of excess cytoplasmic domain of VAMP2 or SYN/SNAP-25 (data not shown).

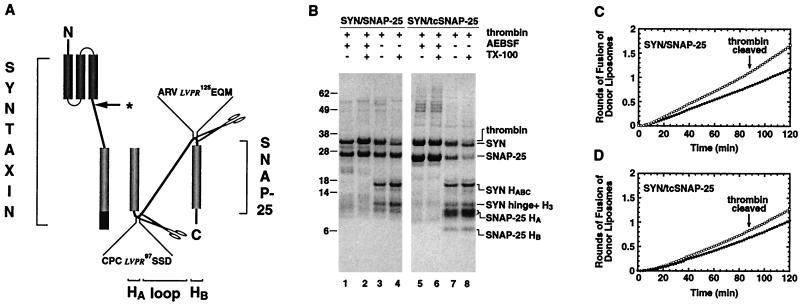

Removal of the Loop Connecting SNAP-25’s Two Helices Does Not Affect Fusion.

The SNAP-25 molecule contains two helical domains, HA and HB, each of which is essential for SNARE complex formation (18, 19). The loop region that connects HA to HB is not necessary for formation of the SNARE complex in solution (14, 18, 19). We next examined whether the SNAP-25 loop region is necessary for membrane fusion. A SNAP-25 molecule was engineered in which the loop region is flanked by thrombin cleavage sites at both ends (Fig. 3A). A t-SNARE consisting of syntaxin and thrombin-cleavable SNAP-25 (SYN/tcSNAP-25), representing the functional t-SNARE, were co-expressed, co-purified, and reconstituted into liposomes. After reconstitution, thrombin was used to excise the SNAP-25 loop region. Two Coomassie blue-stained bands were observed after thrombin digestion (Fig. 3B, lane 7); they correspond to the SNAP-25 HA and HB domains. In addition, two other bands derived from syntaxin were produced due to a cryptic thrombin site within syntaxin (Fig. 3B, lane 7). A control experiment using reconstituted syntaxin/SNAP-25 (SYN/SNAP-25; that is, lacking engineered thrombin sites) in combination with N-terminal sequencing confirmed that the two novel bands generated by thrombin digestion correspond to the syntaxin HABC and the syntaxin H3+hinge domain (Fig. 3B, lane 3; see Fig. 3 legend). This unexpectedly limited proteolysis of syntaxin is an unavoidable consequence of digestion with thrombin under these conditions.

Figure 3.

Excision of the SNAP-25 loop region has little effect on fusion. (A) Schematic representation of syntaxin, and the SNAP-25 HA HB helices and the loop domain. SNAP-25 amino acids 93–96 (NKLK) and 121–124 (VDER) were substituted with the thrombin recognition sequence LVPR. The arrow with asterisk indicates the position of the cryptic thrombin cleavage site in syntaxin (see below). (B) Coomassie blue-stained protein profile of SYN/SNAP-25 and SYN/tcSNAP-25 before and after thrombin treatment. SYN/SNAP-25 (lanes 1–4) and SYN/tcSNAP-25 (lanes 5–8) were purified and reconstituted into liposomes. These proteoliposomes were treated with either inactive thrombin (lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6) or active thrombin (lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8) for 4 hours at 37°C in the presence (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) or absence (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) of TX-100. Because syntaxin contains a cryptic thrombin cleavage site in its hinge domain, this proteolysis resulted in an unengineered cleavage of the HABC domain from the hinge H3 domain in some syntaxin molecules. N-terminal sequencing of the SYN hinge+H3 band revealed the sequence 159TTTSEE, confirming that thrombin had severed the SYN HABC domain from the hinge+H3 domain. AEBSF, 4-2(aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride. Shown are kinetic profiles of membrane fusion of SYN/SNAP-25 (C) or SYN/tcSNAP-25 (D) liposomes before and after thrombin treatment with v-liposomes. Donor vesicles containing VAMP were mixed with full length SYN/SNAP-25 or SYN/tcSNAP-25 (closed circles) or thrombin-treated SYN/SNAP-25 or SYN/tcSNAP-25 (open circles) liposomes, and the increase in NBD fluorescence at 37°C was monitored for 2 hours. This increase in NBD fluorescence then was converted to rounds of fusion, as described above. We repeatedly observed a slight lag in the initial rate of fusion when the loop region of SNAP-25 was excised.

The thrombin-cleaved SYN/tcSNAP-25 liposomes fused with slightly faster kinetics than its uncleaved counterpart (Fig. 3D, open circles vs. closed circles). Because control t-liposomes (SYN/SNAP-25, lacking the engineered sites within SNAP-25) show a similar enhancement in fusion kinetics upon treatment with thrombin (Fig. 3C), we conclude that removing the SNAP-25 loop domain neither enhances nor inhibits fusion. This enhancement in rate attributable to cleavage at the cryptic thrombin site in syntaxin, which removes the HABC domain but not the hinge region, is consistent with our previous result demonstrating a substantial increase in fusion when both HABC and the hinge are removed (Fig. 2C).

It is worth noting that the introduction of the thrombin sites in SNAP-25 (even without cleavage) significantly diminished the initial kinetic advantage gained during low-temperature preincubation without affecting the overall fusion kinetics (data not shown), a phenomenon that will require further investigation beyond the scope of this study.

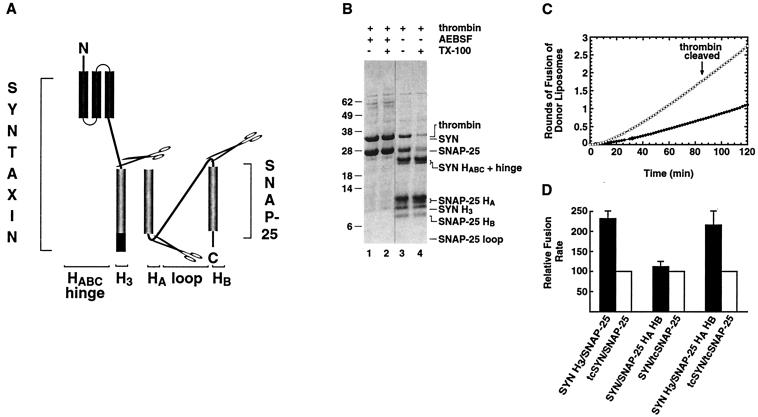

Fusion by the α-Helical Core Domain.

To test the fusogenic capacity of the helical bundle comprising the proteolytic core of the SNARE complex (18, 19), essentially the same structure reported from x-ray crystallography (14), we combined the various cleavage sites in a single species of t-SNARE. Thus, thrombin-cleavable syntaxin and thrombin-cleavable SNAP-25 (tcSYN/tcSNAP-25) were co-expressed, purified, reconstituted into t-liposomes, and thrombin-cleaved (Fig. 4B). After the thrombin cleavage, five bands were now observed, all of which were predicted based on the earlier work: syntaxin HABC+hinge, SNAP-25 HA, syntaxin H3, SNAP-25 HB, and the SNAP-25 loop (not visible because of poor Coomassie blue staining) (Fig. 4B, lane 3). The identity of all of these bands was confirmed by N-terminal sequencing. The SYN H3+hinge fragment seen in Fig. 3 (asterisks) was no longer present, presumably because of further cleavage at the site engineered between the hinge and H3. The liposomes bearing uncleaved tcSYN/tcSNAP-25 t-SNAREs (Fig. 4C, solid circles) fused with similar kinetics to the natural t-SNARE sequence (Fig. 1D, open circles). After thrombin cleavage (Fig. 4C, open circles), SYN H3/SNAP-25 HAHB liposomes behaved similarly to SYN H3/SNAP-25, showing a significant enhancement in the rate of fusion.

Figure 4.

The t-SNARE core domain is sufficient to efficiently drive membrane fusion. (A) Schematic representation of the engineered thrombin cleavage sites in both syntaxin and SNAP-25. The thrombin sites are at the same positions as described in Figs. 2 and 3. After thrombin proteolysis, the membrane proximal syntaxin H3 and SNAP-25 HA HB helices were severed from all other t-SNARE domains. (B) Coomassie blue-stained protein profile of tcSYN/tcSNAP-25 before and after thrombin treatment. The tcSYN/tcSNAP-25 heterodimer was purified and reconstituted into liposomes and was treated with either inactive thrombin (lanes 1 and 2) or active thrombin (lanes 3 and 4) for 4 hours 37°C in the absence (lanes 1and 3) or presence (lanes 2 and 4) of 0.2% TX-100 to access the lumenally oriented tcSYN/tcSNAP-25 complex. AEBSF, 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride. (C) Kinetic profile of membrane fusion of tcSYN/tcSNAP-25 and SYNH3/SNAP-25 HAHB liposomes with v-liposomes. Donor liposomes containing VAMP were mixed with acceptor liposomes containing either full length (closed circles) or core t-SNAREs (open circles) and were allowed to fuse at 37°C without any preincubation. The increase in NBD fluorescence was monitored and converted to rounds of fusion. (D) Comparison of fusion efficiency of SYN H3/SNAP-25, SYN/SNAP-25 HAHB, and SYN H3/SNAP-25 HAHB liposomes with VAMP liposomes. The rounds of fusion after 2 hours at 37°C of the reaction for SYN H3/SNAP-25 (n = 18, independent experiments), SYN/SNAP-25 HAHB (n = 5), and SYN H3/SNAP-25 HAHB liposomes (n = 19) liposomes (filled histograms) were compared with their respective full length counterpart (open histograms) and were expressed as percent of full length protein signal. The SYN H3/SNAP-25 and SYN H3/SNAP-25 HAHB liposomes have a higher fusion efficiency than full length t-SNAREs (232 ± 32% and 216 ± 34%, respectively); SYN/SNAP-25 HAHB has a slightly higher fusion efficiency (112 ± 13%) compared with its full length counterpart.

The relative fusion rates for various t-SNAREs are compared in Fig. 4D, averaged over many experiments. They demonstrate that the core four-helical bundle including a helix from the v-SNARE, VAMP, not only retains the capacity for fusion but does so at more than twice the overall speed of full-length SNAREs.

Discussion

SNARE-mediated fusion of artificial lipid bilayers can be at least as efficient and as fast as SNARE-dependent fusion of isolated natural membrane fractions or in permeabilized cells. Concerning efficiency, incubation of v-liposomes with excess of t-liposomes results in at least 1.5–2 rounds of fusion with t-liposomes containing full length t-SNAREs (Fig. 1D) and can result in at least 5–6 rounds of fusion with t-liposomes containing a truncated syntaxin missing the N-terminal (Habc+hinge) domain (Fig. 2C).

Concerning speed, with full length proteins, the time for completion of half a round of fusion after docking during preincubation at 4°C is ≈7 min (Fig. 1E), as compared with a half-time of ≈40 min for one round of fusion when using nonpreincubated liposomes (Fig. 1D). When the N-terminal domain (Habc+hinge) of syntaxin is removed, the half-time for the overall fusion process (i.e., without preincubation) is now 10 min (Fig. 2C), similar to the time required for half a round of fusion after docking at low temperature. Thus, it appears that functional docking is the rate-limiting step with full length syntaxin. When the N-terminal domain of syntaxin is removed, functional docking is now faster, and fusion becomes rate-limiting.

Interestingly, the N-terminal domain of syntaxin does not affect the rate of reaction of syntaxin/SNAP-25 complexes with VAMP (21). The initial contact between v- and t-SNAREs (containing full length syntaxin) occurs within a few minutes after liposome bearing these SNAREs are mixed. Previous studies showed that the N-terminal domain of the syntaxin homologue Sso1p greatly slows the rate of its reaction with the SNAP-25 homologue Sec9p (21). Our data indicate that the N-terminal domain of syntaxin also has a regulatory role at the level of SNARE-dependent fusion after the initial binding of v- and t-SNAREs bridging the liposomes. Presumably, other proteins present in cells act on this domain in SNARE complexes to permit fusion to proceed at the maximum speed allowed by the core complex. Whether the N-terminal domain slows “zipping up” of SNARE complexes (6, 22), regulates the assembly of a possible oligomeric “ring” (18, 19), or acts otherwise is presently unknown.

It has been postulated that the SNAP-25 “loop” region linking its two α-helices may permit the formation of multimeric SNARE complexes if SNARE complexes can assemble with A and B helices derived from different SNAP-25 molecules (18, 19). This possibility requires that the two helices be covalently linked. However, SNARE complexes composed with separated helix A and helix B domains are fusion-competent in permeabilized cells (8) and now with isolated SNAREs (Figs. 3D and 4C).

How does the speed of fusion by the core complex compare with the speed of fusion after SNARE assembly in cell-free systems using natural membranes that should contain these SNARE proteins? The half-time for release of stored transmitter from permeabilized neuroendocrine cells (PC12 cells) is 5–9 min (see Fig. 8 in ref. 8). These kinetics are both SNARE- and calcium-dependent and are sensitive to mutations in key residues of SNAP-25 that participate in the helical bundle (14). This compares with ≈10-min half-time for fusion by isolated SNARE cores (Fig. 2C). Exocytosis in intact neuroendocrine cells has been well studied by bulk transmitter release (23, 24). The time required for exocytosis of half of the total releasable pool of neurotransmitter after maximum calcium stimulation is ≈5 min (25, 26).

If, hypothetically, the ≈30,000 storage vesicles in a neuroendocrine cell (23, 27, 28) were to be replaced by an equal number of our liposomes containing pure v-SNAREs, and, if the protein in the plasma membrane were replaced by truncated t-SNAREs (fusing with the observed half-time of 10 min), then the first liposome can be simply calculated to fuse with the plasma membrane within ≈15 msec. Liposomes located by design (29, 30) or by chance nearer the plasma membrane would fuse even faster than this, well within the range of many estimates of quantal release in such cells (31, 32). This simple calculation reveals the underlying self-consistency of the half-time for fusion of a vesicle population (in minutes) and the timing of individual events (in milliseconds) in terms of a single underlying mechanism involving fusion by SNARE proteins. In short, there can be little doubt of the kinetic competence of fusion by isolated SNAREs or its relevance to bilayer fusion.

A central finding of this work is that a limited portion of the SNARE complex consisting only of the helical bundle can mediate fusion of liposomes. This finding supports a simple model in which the central event in cellular membrane fusion is mediated by a SNAREpin linking two lipid bilayers that assembles from two parts, v-SNAREs and t-SNAREs present in different membranes (7, 14, 33). When these two “half-pins” link up, their respective membranes are drawn together, and membrane fusion occurs.

In the case of viral fusion, what can be thought of as two corresponding half-pins are covalently attached, synthesized together in a single fusion protein (7, 15). However, the native structure of the fusion protein in its resting state prevents the full pin from forming (15). Upon activation (at the surface of a cell or in an endosome), this constraint is thought to be released so the half-pins can assemble into a complete hairpin linking the viral to the cellular membrane and fusion can ensue.

Although the hairpin-like helical bundle structure is a well established feature of isolated proteolytic fragments of viral fusion proteins (15), it remains to be directly established that these viral hairpins are actually fusion-competent structures. Our finding that the analogous pin-like helical bundle of the SNARE complex is fusion-competent considerably strengthens the argument that the simplest imaginable structure—a pin—provides a general principle for biological membrane fusion, forcibly linking the two membranes into which it is simultaneously inserted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Walter Nickel and Christine Hughes for constructive comments on the manuscript and Dr. Hediye Erdjument-Bromage and the Microchemistry Core Facility of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center for protein sequencing. We thank Mr. Bob Johnston for technical assistance and Mr. Joshua Olesker for help with preparation of the manuscript. Research was supported by a National Institute of Health grant (to J.E.R.) and postdoctoral fellowships of the Medical Research Council of Canada (to F.P.), Swiss National Science Foundation (to T.W.), European Molecular Biology Foundation (to T.W.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to B.W.), and the National Institutes of Health (to J.M.).

Abbreviations

- SYN/SNAP-25

syntaxin1/His6SNAP-25

- tcSYN-SNAP-25

thrombin-cleavable syntaxin1/His6SNAP-25

- SYN/tcSNAP-25

syntaxin1/thrombin-cleavableHis6SNAP-25

- tcSYN/tcSNAP-25

thrombin-cleavable syntaxin1/thrombin-cleavableHis6SNAP-25

- NBD

7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole

- VAMP2

vesicle-associated membrane protein 2

- PE

1,2-dipalmitoyl phosphatidylethanolamine

Footnotes

See commentary on page 12227.

References

- 1.Söllner T, Whiteheart S W, Brunner M, Erdjument-Bromage H, Geromanos S, Tempst P, Rothman J E. Nature (London) 1993;362:318–324. doi: 10.1038/362318a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lian J P, Ferro-Novick S. Cell. 1993;73:735–745. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90253-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nichols B J, Ungermann C, Pelham H R, Wickner W T, Haas A. Nature (London) 1997;387:199–202. doi: 10.1038/387199a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saifee O, Wei L, Nonet M L. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1235–1252. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.6.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sato K, Wickner W. Science. 1998;281:700–702. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5377.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz L, Hanson P I, Heuser J E, Brennwald P. EMBO J. 1998;17:6200–6209. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weber T, Zemelman B V, McNew J A, Westermann B, Gmachl M, Parlati F, Söllner T H, Rothman J E. Cell. 1998;92:759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y A C, Scales S J, Patel S M, Doung Y C, Scheller R H. Cell. 1999;97:165–174. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80727-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nickel W, Weber T, McNew J A, Parlati F, Söllner T H, Rothman J E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12571–12576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanson P I, Roth R, Morisaki H, Jahn R, Heuser J E. Cell. 1997;90:523–535. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin R C, Scheller R H. Neuron. 1997;19:1087–1094. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80399-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohl T M, Parlati F, Wimmer C, Rothman J E, Söllner T H, Engelhardt H. Mol Cell. 1998;2:539–548. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poirier M A, Xiao W, Macosko J C, Chan C, Shin Y K, Bennett M K. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:765–769. doi: 10.1038/1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutton R B, Fasshauer D, Jahn R, Brunger A T. Nature (London) 1998;395:347–353. doi: 10.1038/26412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Cell. 1998;95:871–874. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81710-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughson F M. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R49–R52. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Struck D K, Hoekstra D, Pagano R E. Biochemistry. 1981;20:4093–4099. doi: 10.1021/bi00517a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fasshauer D, Eliason W K, Brunger A T, Jahn R. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10354–10362. doi: 10.1021/bi980542h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poirier M A, Hao J C, Malkus P N, Chan C, Moore M F, King D S, Bennett M K. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11370–11377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fernandez I, Ubach J, Dulubova I, Zhang X, Sudhof T C, Rizo J. Cell. 1998;94:841–849. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81742-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholson K L, Munson M, Miller R B, Filip T J, Fairman R, Hughson F M. Nat Struct Biol. 1998;5:793–802. doi: 10.1038/1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiebig K M, Rice L M, Pollock E, Brunger A T. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:117–123. doi: 10.1038/5803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burgoyne R D. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1071:174–202. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(91)90024-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson L, Martin T. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:483–492. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knight D E, Baker P F. J Membr Biol. 1982;68:107–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01872259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.TerBush D R, Holz R W. J Neurochem. 1992;58:680–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plattner H, Artalejo A R, Neher E. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:1709–1717. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.7.1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parsons T D, Coorssen J R, Horstmann H, Almers W. Neuron. 1995;15:1085–1096. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin T F, Kowalchyk J A. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14447–14453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lang T, Wacker I, Steyer J, Kaether C, Wunderlich I, Soldati T, Gerdes H H, Almers W. Neuron. 1997;18:857–863. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80325-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heinemann C, Chow R H, Neher E, Zucker R S. Biophys J. 1994;67:2546–2557. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80744-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almers W, Lee A K, Shoji-Kasai Y, Takahashi M, Thomas P, Tse F W. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1994;29:97–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanson P I, Heuser J E, Jahn R. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1997;7:310–315. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(97)80057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.