Abstract

The mouse p53 protein generated by alternative splicing (p53as) has amino acid substitutions at its C terminus that result in constitutively active sequence-specific DNA binding (active form), whereas p53 protein itself binds inefficiently (latent form) unless activated by C-terminal modification. Exogenous p53as expression activated transcription of reporter plasmids containing p53 binding sequences and inhibited growth of mouse and human cells lacking functional endogenous p53. Inducible p53as in stably transfected p53 null fibroblasts increased p21WAF1/Cip-1/Sdi and decreased bcl-2 protein steady-state levels. Endogenous p53as and p53 proteins differed in response to cellular DNA damage. p53 protein was induced transiently in normal keratinocytes and fibroblasts whereas p53as protein accumulation was sustained in parallel with induction of p21WAF1/Cip-1/Sdi protein and mRNA, in support of p53as transcriptional activity. Endogenous p53 and p53as proteins in epidermal tumor cells responded to DNA damage with different kinetics of nuclear accumulation and efficiencies of binding to a p53 consensus DNA sequence. A model is proposed in which C-terminally distinct p53 protein forms specialize in functions, with latent p53 forms primarily for rapid non-sequence-specific binding to sites of DNA damage and active p53 forms for sustained regulation of transcription and growth.

Keywords: p53, alternative splicing, DNA binding

p53 suppresses tumors through growth arrest or apoptosis mediated by domains for transcriptional activation (N terminus) and sequence-specific DNA binding (central hydrophobic region). The biological significance of sequence-specific DNA binding is supported by frequent mutations within this domain in human cancers (1–4), correlations between transactivation by p53 and inhibition of cell proliferation (5, 6), and the presence of specific p53 DNA binding sequences in human and mouse genomes (7–9). By specific binding, p53 controls the expression of downstream growth inhibitory factors such as the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21WAF1/Cip-1/Sdi (10–13).

The C terminus of p53 protein contains a negative regulatory domain for sequence-specific DNA binding of the central domain. p53 proteins extracted from mammalian cells (7, 14–16) or produced using recombinant baculovirus (ref. 17 and S. Kaku, A. Albor, and M.K.M., unpublished data) or in vitro transcription/translation systems (14, 18, 19) primarily are latent for sequence-specific DNA binding. Antibody PAb421 is used to activate p53 in vitro, but endogenous activation pathways remain to be defined (20). Alternative splicing is a candidate for activation of p53 in mouse cells because p53as mRNA is in normal cells and tissues (21) and p53as protein is differentially detectable compared with p53 during the cell cycle (22) and, expressed independently of p53, is constitutively active for sequence-specific DNA binding (18, 23, 24).

We examined p53as protein capability for growth arrest and transcriptional activation and compared the responses to DNA damage of p53 and p53as proteins expressed from the wild-type p53 gene in cells. Differential kinetics of induction after DNA damage was observed, suggesting that latent and active sequence-specific binding forms of p53 are differentially regulated. The evidence for distinct functional forms of p53 suggests a model for dissecting multiple roles of p53 relevant to carcinogenesis and cancer treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies.

Monoclonal antibodies PAb421 or PAb122 (p53 C terminus), mp21, and polyclonal ApAs antibody (p53as) (22) were from Oncogene Research Products. Monoclonal antibody 6.2 binds p53 and p53as (Gly-299 to Ser-364). Polyclonal anti-bcl-2 was obtained from PharMingen, and anti-Hsp70 was from StressGen Biotechnologies, Victoria, Canada.

Plasmids.

Plasmids pmMTp53 and pmMTp53as contain p53 and p53as cDNA, respectively, which have been inserted into the BamHI and BglII sites of pmMTVal135 (gift of M. Oren, The Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel) downstream of an inducible metallothionein promoter. Plasmids pCMVp53 and pCMVp53as were constructed by replacing human p53 cDNA with mouse p53 or p53as in plasmid p53C-SN (gift of S. Friend, Fred Hutchinson CRC, Seattle). Reporter plasmids WWP (WAF1 promoter) (12), PG13CAT (13 copies of a synthetic p53 consensus sequence) (9), and MG13CAT (15 copies of a mutated consensus) were provided by B. Vogelstein (The John Hopkins University, Baltimore). Plasmid WT-30 [cyclin G promoter (25)] was provided by D. Beach (Cold Spring Harbor Labs., New York).

Cell Culture, Transfections, and Treatments.

Cells lacking endogenous p53 expression, Saos2 human osteosarcoma, and (10)1 mouse embryonic fibroblasts (26) (gift of A. Levine, Princeton University) were maintained in DMEM plus 10% fetal calf serum. Nontransformed mouse keratinocyte clone 291 retains normal cell properties in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (EMEM) containing 0.04 mM calcium, 10 ng/ml EGF, dermal fibroblast conditioned media, and 5% fetal calf serum (27, 28). Squamous cell carcinoma line 291.05RAT (29), a dimethylbenz[α]anthracene-induced derivative of 291, was maintained in EMEM containing 1.4 mM calcium and 5% fetal calf serum. Dermal fibroblasts were freshly isolated (30) and passaged once in EMEM containing 1.4 mM calcium and 10% fetal calf serum. Transient transfections were performed using calcium precipitation (31); stable transfections were performed using Lipofectin (GIBCO/BRL). Cells were treated with 60 μM genistein (Sigma) in culture medium diluted from a 60-mM DMSO stock, or with 400 rads of x-ray delivered from a Westinghouse Quadrocondex with Siemen’s Therapy X-ray tube followed by recovery in routine culture.

Growth Inhibition Assays.

Saos2 cells were transfected with 5 μg of pCMVp53 or pCMVp53as expression vector containing a neo gene, subcultured 40–48 hr later, and selected in 400 μg/ml G418 for 3 weeks. Cells were fixed in methanol, stained with Giemsa, and total colony area per dish was determined using the dishmeasure imaging program (Applied Instruments). Stable (10)1 transfectants containing integrated pmMTp53 or pmMTp53as were seeded at 2,000 cells per well in 96-well plates and grown for 24 hr before induction of p53 or p53as expression by 3 μM CdCl2 (time = 0). Cells were quantified by dye uptake (absorbance at 570 nm) relative to blanks without cells (CellTiter 96 kit, Promega).

Chloramphenicol Acetyl Transferase and Luciferase Assays.

Three micrograms of reporter plasmid DNA was cotransfected with 10 ng of pCMVp53as, pCMVp53, or pCMV in (10)1 cells. After 48 hr, cells were lysed and 100 or 20 μl of supernatant was used for measuring chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (32) or luciferase activity (Promega), respectively. Transactivation was expressed relative to pCMV plasmid controls and standardized to total cellular protein (Micro BCA Kit, Pierce).

Cell Extracts and Immunoblotting.

Cells were seeded at 3.5 × 106/150-mm plate, incubated at 37°C overnight, treated as above, and harvested at the times indicated. Whole-cell extracts were prepared (33) for Western immunoblotting (or DNA binding, below). Equal amounts of protein were resolved in 10% polyacrylamide/SDS gels and transferred to nitrocellulose. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in TBS-T (20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.6/137 mM NaCl/0.05% Tween-20) at 4°C overnight, then blotted with primary antibody for 2 hr and secondary antibody for 1 hr. Bands were visualized by chemiluminiscence (ECL, Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories).

Northern Analysis.

Total RNA was isolated using an Ultraspec system (Biotecx). Seven micrograms of RNA per lane was separated in 1.2% formaldehyde agarose, transferred to Nytran Plus (Schleicher & Schuell), and probed with a WAF1/p21-specific 738-bp fragment of pCMN35 (gift of B. Vogelstein) radiolabeled using Multiprime (Amersham).

Indirect Immunofluorescence.

Cells were seeded at 5 × 104 per 18 × 18-mm coverslip 24 hr before treatment, fixed in cold methanol at the times indicated, and immunostained as described previously (22).

DNA Binding Assays.

Equal amounts of protein were incubated with 2 μg poly[d(I-C)] with or without 200 ng of antibody in 20 μl of DNA binding buffer (20 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.2/80 mM NaCl/1 mM EDTA/0.1% Triton X-100/4% glycerol/5 mM DTT) at 4°C for 20 min (18). 32P end-labeled consensus p53 binding sequence DNA [30,000 cpm (≈1 ng)] (5′-AGGCATGCCTAGGCATGCCT-3′; ref. 9) was added, and reactions were incubated for 20 min. Electrophoresis was carried out in 4% nondenaturing agarose in 0.5× TBE at 4°C and visualized by autoradiography.

RESULTS

Growth Inhibition.

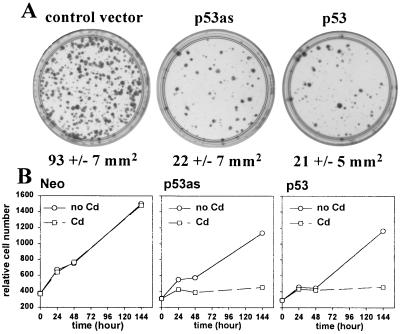

p53as expressed constitutively from a cytomegalovirus promoter inhibited Saos2 colony formation similarly to p53 (Fig. 1A), demonstrating that p53as arrested human cell growth. Growth of (10)1 mouse cell stable transfectants also was inhibited following induction of p53as or p53 by Cd2+ via the metallothionein promoter, with plasmid controls unaffected (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Growth inhibition assays. (A) Saos2 cells were transfected with plasmids containing a neo resistance gene and either no insert, p53, or p53as cDNA. After selection in G418 for 3 weeks, fixed cells were stained with Giemsa. Mean total colony area (mm2) per four 60-mm dishes is shown. The data were consistent in two experiments. (B) Stable (10)1 fibroblast clones containing neo resistance control plasmid, alone or cotransfected with plasmids containing inducible p53as (representative of two clones with integrated p53as), or p53 (four clones), were exposed to CdCl2 (0 hr), and relative cell number was determined as described in Materials and Methods.

Downstream Genes and Transcription.

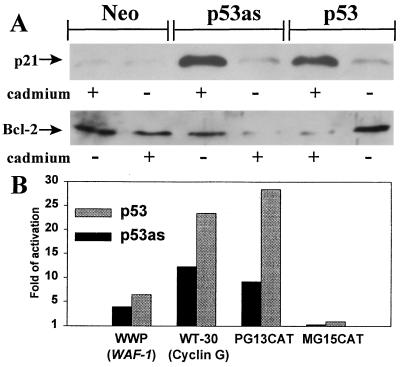

Induction of p53as or p53 by Cd2+ in stable (10)1 transfectants increased p21 and decreased bcl-2 accumulation similarly (Fig. 2A). Transactivation was more directly assessed by transient cotransfections of pCMVp53 or pCMVp53as expression plasmids, with reporter plasmids containing p53 DNA binding sequences. As shown in Fig. 2B, p53as expression transactivated WAF1 (WWP) and cyclin G promoters (WT-30). Transactivation by p53as was sequence-specific, activating PG13CAT but not MG13CAT.

Figure 2.

Effects on p53 downstream genes in (10)1 cells. (A) Stable inducible p53, p53as, or neo control cell clones were exposed to CdCl2 as in Fig. 1B. After 18 hr cells were lysed and 50 μg of protein/lane was immunoblotted using anti-p21 or anti-bcl-2 antibodies. (B) Transactivation of reporter plasmids transiently cotransfected with pCMVp53as, pCMVp53, or pCMV. Cells were lysed after 40–48 hr, and chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (PG13, MG15) or luciferase activity (WWP, WT-30) was measured, standardized to total protein, and expressed relative to pCMV control as 1. Fold activation in three replicate experiments was 3–20 (WWP), 5–18 (WT-30), and 9–15 (PG13).

Responses of Endogenous p53as and p53 Proteins.

The activities of exogenous p53as and p53 in cells suggested that p53as can act as a tumor suppressor. We therefore examined p53 and p53as proteins expressed from the endogenous p53 gene in response to DNA damage.

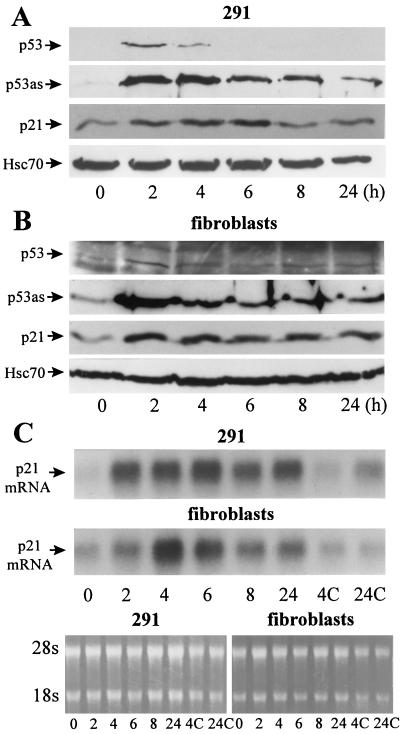

In epidermal 291 cells, the latent p53 protein recognized by PAb421 or PAb122 was rapidly and transiently induced, peaking 2 hr postirradiation (Fig. 3A). In contrast, induction of p53as protein was sustained for at least 24 hr and correlated with induction of p21 protein. In x-irradiated secondary fibroblasts, p53 protein was either undetectable by PAb421 or PAb122 or barely detectable (Fig. 3B; note high background), again peaking at 2 hr. As in epidermal cells, p53as protein was induced by 2 hr, maintained for at least 24 hr, and correlated with accumulation of p21 protein (Fig. 3B). Northern blots (Fig. 3C) revealed that waf1 mRNA also was sustained (Fig. 3C), consistent with transcriptional regulation by p53as protein.

Figure 3.

Response to x-ray (400 rads) of normal (A) 291 epidermal cells or secondary mouse fibroblasts (B) detectable by Western immunoblotting. Proteins were extracted at the indicated times postirradiation and reacted with PAb122 (p53), ApAs (p53as), mp21 (p21), or anti-Hsc70 as loading control. (C) Northern blots. Cells were lysed and 7 μg total RNA per lane was separated in 1.2% formaldehyde agarose, transferred to a membrane, and probed using a radiolabeled fragment of mouse p21/waf1 cDNA. Controls included ethidium bromide staining of rRNA (for loading) and cells exposed to solvent for 4 (4C) or 24 hr (24C).

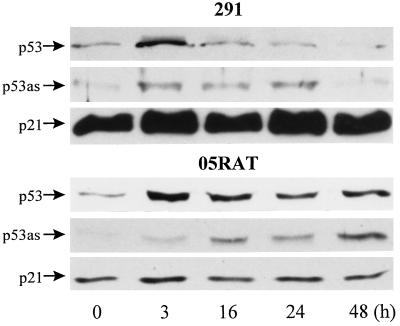

The DNA-damaging agent genistein [a tyrosine kinase (34) and topoisomerase II inhibitor (35) that causes protein-linked DNA strand breaks (36, 37)] also induced rapid accumulation of p53 and sustained accumulation of p53as proteins in 291 and its carcinoma derivative, 291.05RAT (Fig. 4). Steady-state levels of p21 protein were not appreciably increased by genistein-induced arrest in G2 (confirmed by flow cytometry, data not shown), consistent with a role of p21 predominantly in G1 arrest.

Figure 4.

Response to 60 μM genistein detectable by immunoblotting. 291 cells and derivative tumor cells 291.05RAT (05RAT) were treated for the times indicated, and proteins were extracted and analyzed as in Fig. 3.

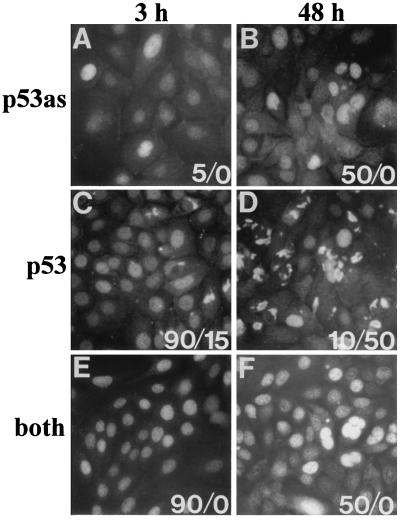

Indirect immunofluorescence of 291.05RAT cells indicated p53as antigen activity was nuclear (as reported in ref. 22), accumulated gradually, and was sustained for 48 hr (Fig. 5A and B), whereas increased nuclear PAb421 reactivity was rapid but transient (Fig. 5 C and D). Total p53 protein was confirmed using antibody 6.2 (Fig. 5 E and F). Loss of PAb421 reactivity in the nucleus was accompanied by focal accumulation in the cytoplasm in 4/6 experiments (Fig. 5 C and D). Cytoplasmic PAb421 reactivity appeared to be specific, being undetectable in genistein-treated p53 null keratinocytes (data not shown), but was not corroborated by binding to 6.2.

Figure 5.

p53as and p53 detection by indirect immunofluorescence. 291.05RAT cells were treated with 60 μM genistein for the times indicated, fixed, and immunostained with ApAs (p53as), PAb421 (p53), 6.2 (both), or IgG/preimmune controls (negative, i.e., <1 staining intensity on scale of 1 to 4; data not shown). Positive cells (intensity, 2.5–4) per total cells per coverslip (%) for nuclear/cytoplasmic staining are shown (at 0 hr, 0.1–5% reacted with antibodies). The peak nuclear antibody reactivity for PAb421 (3 hr) and for ApAs (24–48 hr) is representative of six experiments.

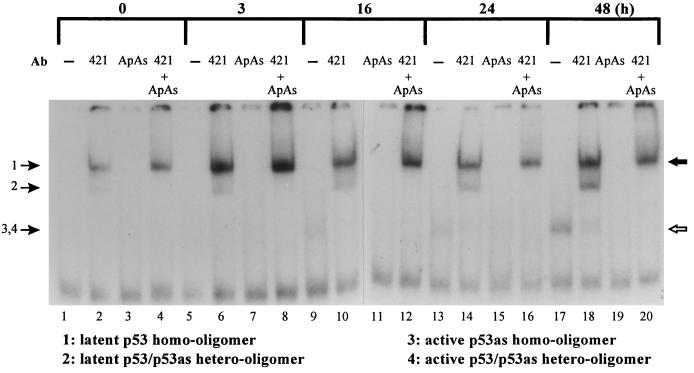

Distinct Induction of the Latent and Active DNA-Binding Forms.

Sequence-specific DNA binding of 291.05RAT cell proteins revealed that latent forms of p53 were induced rapidly, peaking at 3 hr, whereas active forms of p53 were detectable between 16 and 48 hr after genistein treatment (Fig. 6), consistent with the timing of induction of p53 and p53as proteins detectable by immunoblotting (Fig. 4B). Three of the observed complexes were identical to those characterized previously in electrophoretic mobility-shift assay reactions using proteins translated in vitro: p53 (complex 1), p53as (complex 3), and both forms cotranslated (complex 2); see figures 2A and 3 in ref. 18. p53 protein was latent in untreated cells, being undetectable in the absence of PAb421 (Fig. 6, lane 1). Latent p53 protein forms (complexes 1 and 2) detectable in the presence of PAb421 were induced rapidly after DNA damage (Fig. 6, lanes 6, 10, 14, and 18). Complex 1 contains latent p53 homooligomers that are activated and supershifted by PAb421 and unaffected by p53as antibody (ApAs). Complex 2 contains latent p53/p53as heterooligomers that are activated and supershifted by PAb421 and lost in the presence of ApAs (Fig. 6, lanes 4, 8, 12, 16, 20; ref. 18). In contrast, active sequence-specific binding complexes 3 and 4 (detected in the absence of PAb421) appeared 16–48 hr after genistein treatment (Fig. 6, lanes 9, 13, and 17). Complex 3 is a p53as homooligomer (not supershifted by PAb421, compare lane 18 with lane 17, and lost with ApAs, lane 19) that migrated similarly to complex 4, a p53/p53as heterooligomer (supershifted by PAb421, lane 18, and lost with ApAs, lanes 19 and 20). The lack of active p53 homooligomers in complexes 3 and 4 is verified by the abrogation of binding by ApAs antibody alone; compare lanes 19 and 17.

Figure 6.

Electrophoretic mobility-shift assay. 291.05RAT cells were harvested at the times indicated after treatment with 60 μM genistein. Equal amounts of protein were reacted with a 32P-labeled p53 consensus DNA sequence in the presence or absence of 200 ng of the antibodies indicated and visualized by autoradiography. The positions of migration of baculovirus-purified recombinant human p53 + PAb421 (solid arrow) and mouse p53as (open arrow) are shown. Free probe migrated at twice the distance of the rapidly migrating (unlabeled) nonspecific band and was present in vast excess of the signals shown.

DISCUSSION

The current results indicated that wild-type p53as protein is functional in growth arrest and carries out biological activities of the p53 gene in response to DNA damage. Exogenously expressed p53as inhibited human and mouse cell growth, regulated downstream gene expression, and transactivated reporter genes containing p53 binding sites. Differential responses to DNA damage of p53 and p53as proteins in cells included: (i) distinct kinetics of induction, (ii) correlation of p53as protein induction by x-ray with increases in p21 protein and waf1 mRNA levels, (iii) efficient sequence-specific DNA binding by p53as oligomers at distinct times from peak induction of latent p53 forms, and (iv) distinct timing of nuclear accumulation.

These results are consistent with those of others that show rapid and transient increases in p53 protein levels detectable by PAb421 (38), where proteins detectable by a mixture of p53 antibodies to regions shared by p53as and p53 were sustained in cells after DNA damage along with p21 protein levels (39, 40) and G1 arrest. Furthermore, changes at the C terminus that activate p53 can render it undetectable by PAb421 (17, 41).

Early but transient induction of p53 and early but sustained induction of p53as were seen by immunoblotting in normal cells treated with x-ray or genistein. DNA binding of active p53as forms, however, was not reproducibly detectable in normal cells, most likely due to low levels of expression. The detection of p53 and p53as DNA binding forms was enhanced by using tumor line 291.05RAT, which expresses levels of wild-type p53 proteins that are 3-fold higher than the progenitor 291 cells (42), and by treatment with genistein, which arrests cells at the G2-M cell-cycle phase (43, 44) in which p53as is preferentially detectable (22). The results shown in Fig. 6 are direct evidence for differential induction of endogenous active and latent p53 forms in response to DNA damage. They also are observations of endogenous p53as homooligomers active for sequence-specific DNA binding, whereas only latent forms (p53 and p53/p53as heterooligomers) were reported previously (18). The detection of active p53/p53as heterooligomers (complex 4, Fig. 6) after genistein treatment implies damage-related cellular activation factors for latent p53 forms because heterooligomers of complex 2 were latent in untreated cells and at 3 hr after treatment and because p53as proteins were inactivated for sequence-specific DNA binding when cotranslated with p53 proteins (18). The differences observed were due to efficiency, not specificity, of DNA binding as recently reported (45).

Distinct responses to DNA damage were apparent from increases in nuclear p53as, coincident with decreases in nuclear p53 and increases in cytoplasmic PAb421 reactivity. Immunodetectable p53 protein has been observed previously in the cytoplasm of nontransformed and tumor cells (46–48). Cytoplasmic functions could include translational repression through binding to mRNAs (49) or complexing with MDM-2, L5 ribosomal protein, and/or 5.8S rRNA (50). p53as protein could interact with MDM-2, but the 5.8S rRNA binding site is lost.

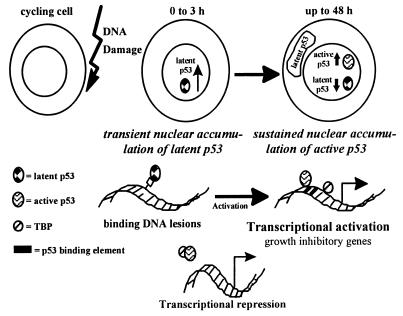

In light of the differential induction of latent and active p53 forms after DNA damage, we speculate that rapidly responding latent p53 forms primarily function in nonspecific binding at sites of damaged DNA and specific recruitment of repair proteins (Fig. 7). Latent p53 also can generally repress transcription by annealing single-stranded nucleic acids or binding to TATA binding protein (51). Once sequence fidelity is assured, active p53 forms carry out transactivation of growth-inhibitory genes, long-lasting growth arrest for DNA repair, apoptosis (15, 39, 52–55), or cell differentiation (56, 57). Latent p53 forms may be destabilized or converted to active forms. Activation of p53 at sites of repair by binding to other cellular proteins or to the single-stranded oligonucleotide by-products of nucleotide excision repair (58) would facilitate local transactivation of only intact sequences. If not converted to an active form, latent p53 might be locally destabilized once repair has occurred and/or exported to the cytoplasm for degradation, sequestration, or other functions.

Figure 7.

Model: p53 forms respond to DNA damage with distinct kinetics. The p53 forms latent for sequence-specific DNA binding are induced rapidly and specialize in nonspecific DNA binding at sites of DNA damage. Transcription is inhibited through catalysis of strand annealing or by binding to TATA box binding protein (TBP). Forms of p53 active for sequence-specific DNA binding are sustained to evoke long-lasting effects on p53 downstream gene transcription, growth arrest, apoptosis, or cell differentiation. Latent p53 may be activated through posttranslational modifications or binding to single-stranded DNA by-products of nucleotide excision repair, targeting sequence-specific transcriptional effects to sites of intact DNA.

Consistent with this model are p53 protein functions that do not depend on sequence-specific DNA binding. p53 binds to single-stranded DNA ends, insertion/deletion mismatches, and mismatches resulting from DNA replication errors after cellular exposure to irradiation or mutagens (59–61). Bound p53 catalyzes DNA renaturation and strand transfer (61–63), activities characteristic of DNA damage repair and recombination. p53 binds through its C terminus to ERCC3/XPB and ERCC2/XPD, components of the basal transcription factor TFIIH (64). The C-terminal 75 amino acids of p53 are required for binding to mismatched DNA and recognition of DNA damage after ionizing radiation (60). p53 has been linked to DNA damage/repair sites by in situ end labeling of DNA in individual cells (65). Wu et al. (63) showed that p53 but not p53as protein carried out single-stranded DNA binding and annealing. Both p53 and p53as can inhibit transcription by interactions with TATA binding protein (H.H. and M.K.M., unpublished data). The biochemical differences between latent and active forms must be tested directly to determine whether active p53 forms lose certain functions of latent p53 or simply acquire an additional function (i.e., efficient binding and transactivation).

Potential endogenous p53 protein activation pathways in response to DNA damage, besides alternative splicing, include modifications at the C terminus: O-glycosylation (41), phosphorylation (14, 17, 66, 67), proteolysis (68), or binding of p53 to other proteins (69). Engineered mutations can regulate the DNA binding and antiproliferative activities of p53, and murine p53 phosphorylations have been demonstrated (70–75). Alternatively spliced p53 gene products in human cells with the functional properties of mouse p53as have not been reported. However, mouse p53as was active in human cells, and human p53 protein, like mouse p53, is predominantly latent. Given the sequence conservation of p53 protein among species, it is likely that mouse and human p53 proteins undergo the same activation steps and that human p53 forms activated through C-terminal modifications are functional equivalents of mouse p53as.

Distinct functions and regulation of latent and active p53 forms in cells would have implications for carcinogenesis and therapy. Active and latent p53 forms could be differentially lost or regulated during tumorigenesis. Inherently active forms of p53 may be preferable for cancer therapy, because they would not depend on activating factors in tumor cell targets. Studies of mouse p53as protein may suggest induction conditions and potential functions of active p53 forms in human cells in response to DNA damage.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nicholas Kisiel for assistance in preparation of this manuscript, Barbara Lisafeld and Laura Lee for technical support, Shinsuke Kaku for recombinant p53 and p53as proteins, and Drs. William Burhans, Margot Ip, and Michael Mowat for critical comments. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA31101 and Institute core CA16056.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

References

- 1.Pavletich N P, Chambers K A, Pabo C O. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2556–2564. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollstein M, Rice K, Greenblatt M S, Soussi T, Fuchs R, Sorlie T, Hovig E, Smith-Sorenson B, Montesano R, Harris C C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3551–3555. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho Y, Gorina S, Jeffery P D, Pavletich N P. Science. 1994;265:346–355. doi: 10.1126/science.8023157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bargonetti J, Manfredi J J, Chen X, Marshak D R, Prives C. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2565–2574. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ory K, Legros Y, Auguin C, Soussi T. EMBO J. 1994;13:3496–3504. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pietenpol J A, Tokino T, Thiagalingam S, el Diery W S, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1998–2002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Funk W D, Pak D T, Karas R H, Wright W E, Shay J W. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:2866–2871. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.6.2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kern S E, Kinzler K W, Bruskin A, Jarosz D, Friedman P, Prives C, Vogelstein B. Science. 1991;252:1708–1711. doi: 10.1126/science.2047879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Deiry W S, Kern S E, Pietenpol J A, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Nat Genet. 1992;1:45–49. doi: 10.1038/ng0492-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu Y, Turck C W, Morgan D O. Nature (London) 1993;366:707–710. doi: 10.1038/366707a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper J W, Adami G R, Wei N, Keyomarsi K, Elledge S J. Cell. 1993;75:805–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90499-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Deiry W S, Tokino T, Velculescu V E, Levy D B, Parsons R, Trent J M, Lin D, Mercer W E, Kinzler K W, Vogelstein B. Cell. 1993;75:817–825. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiong Y, Hannon G J, Zhang H, Casso D, Kobayashi R, Beach D. Nature (London) 1993;366:701–704. doi: 10.1038/366701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hupp T R, Meek D W, Midgley C A, Lane D P. Cell. 1992;71:875–886. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90562-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kastan M B, Zhan Q, El Deiry W S, Carrier F, Jacks T, Walsh W V, Plunkett B S, Vogelstein B, Fornace A J. Cell. 1992;71:587–597. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tishler R B, Calderwood S K, Coleman C N, Price B D. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2212–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hupp T R, Lane P D. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18165–18174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.18165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Y, Liu Y, Lee L, Miner Z, Kulesz-Martin M. EMBO J. 1994;13:4823–4830. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06808.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halazonetis T D, Davis L J, Kandil A N. EMBO J. 1993;12:1021–1028. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05743.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall P A, Meek D, Lane D P. J Pathol. 1996;180:1–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199609)180:1<1::AID-PATH712>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han K A, Kulesz-Martin M F. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:1979–1981. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.8.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulesz-Martin M F, Lisafeld B, Huang H, Kisiel N D, Lee L. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1698–1708. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bayle J H, Elenbaas B, Levine A J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5729–5733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolkowicz R, Peled A, Elkind N B, Rotter V. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6842–6846. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okamoto K, Beach D. EMBO J. 1994;13:4816–4822. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harvey D M, Levine A J. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2375–2385. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12b.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulesz-Martin M, Yoshida M A, Prestine L, Yuspa S H, Bertram J S. Carcinogenesis. 1985;6:1245–1254. doi: 10.1093/carcin/6.9.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulesz-Martin M F, Penetrante R, East C J. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9:171–174. doi: 10.1093/carcin/9.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider B L, Bowden G T, Sutter C, Schweizer J, Han K, Kulesz-Martin M F. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:595–599. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12366051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuspa S H, Koehler B, Kulesz-Martin M F, Hennings H. J Invest Dermatol. 1981;76:144–146. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12525490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pierce A J, Jensen D E, Azizkhan J C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:6583–6587. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.24.6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lassar A B, Davis R L, Wright W E, Kadesch T, Murre C, Voronova A, Baltimore D, Weintraub H. Cell. 1991;66:305–315. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90620-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akiyama T, Ishida J, Nakagawa S, Ogawara H, Watanabe S, Itoh N, Shibuya M, Fukami Y. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5592–5595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markovits J, Linassier C, Fosse P, Couprie J, Pierre J, Jacquemin-Sablon A, Saucier J M, Le Pecq J B, Larsen A K. Cancer Res. 1989;49:5111–5117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Constantinou A, Kiguchi K, Huberman E. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2618–2624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiguchi K, Constantinou A I, Huberman E. Cancer Commun. 1990;2:271–277. doi: 10.3727/095535490820874218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu X, Lane D P. Cell. 1993;75:765–778. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90496-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Leonardo A, Linke S P, Clarkin K, Wahl G M. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2540–2551. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson M, Dimitrov D, Vojta P J, Barrett C, Noda A, Pereira-Smith O M, Smith J R. Mol Carcinog. 1994;11:59–64. doi: 10.1002/mc.2940110202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaw P, Freeman J, Bovey R, Iggo R. Oncogene. 1996;12:921–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Han K, Kulesz-Martin M F. Cancer Res. 1992;52:749–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Traganos F, Ardelt B, Halko N, Bruno S, Darzynkiewicz Z. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6200–6208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsukawa Y, Marui N, Sakai T, Satomi Y, Yoshida M, Matsumoto K, Nishino H, Aoike A. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1328–1331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miner Z, Kulesz-Martin M F. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1319–1326. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.7.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zantema A, Schrier P I, Davis-Olivier A, van Laar T, Vaessen R T, van der Eb A J. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:3084–3091. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.11.3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moudjou M, Paintrand M, Vigues B, Bornens M. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:129–140. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brown C R, Doxsey S J, White E, Welch W J. J Cell Phys. 1994;160:47–60. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haffner R, Oren M. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:84–90. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(95)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marechal V, Elenbaas B, Piette J, Nicolas J C, Levine A J. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7414–7420. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mack D H, Vartikar J, Pipas J M, Laimins L A. Nature (London) 1992;358:281–283. doi: 10.1038/363281a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lane D P. Nature (London) 1992;358:15–16. doi: 10.1038/358015a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuerbitz S J, Plunkett B S, Walsh W V, Kastan M B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:7491–7495. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clarke A R, Purdie C A, Harrison D J, Morris R G, Bird C C, Hooper M L, Wyllie A H. Nature (London) 1993;362:849–852. doi: 10.1038/362849a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clarke A R, Gledhill S, Hooper M L, Bird C C, Wyllie A H. Oncogene. 1994;9:1767–1773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aloni-Grinstein R, Schwartz D, Rotter V. EMBO J. 1995;14:1392–1401. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bogue M A, Zhu C, Aguilar-Cordova E, Donehower L A, Roth D B. Genes Dev. 1996;10:553–565. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.5.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jayaraman L, Prives C. Cell. 1995;81:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee S, Elenbaas B, Levine A, Griffith J. Cell. 1995;81:1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reed M, Woelder B, Wang P, Anderson M E, Tegtmeyer P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9455–9459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bakalkin G, Yakovleva T, Selivanova G, Magnusson K P, Szekely L, Kiseleva E, Klein G, Terenius L, Wiman K G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:413–417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oberosler P, Hloch P, Ramsperger U, Stahl H. EMBO J. 1993;12:2389–2396. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05893.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu L, Bayle J H, Elenbaas B, Pavletich N P, Levine A J. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:497–504. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.1.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang X W, Vermeleulen W, Coursen J, Gibson M, Lupold S, Forrester K, Xu G, Elmore L, Yeh H, Hoeijmakers H J, Harris C. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1219–1232. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.10.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coates P J, Save V, Ansari B, Hall P. J Path. 1995;176:19–26. doi: 10.1002/path.1711760105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oren M, Prives C. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1288:R13–R19. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(96)00030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hao M, Lowy A M, Kapoor M, Deffie A, Liu G, Lozano G. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29380–29385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.29380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Molinari M, Okorokov A L, Milner J. Oncogene. 1996;13:2077–2086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jayaraman L, Murthy K G K, Zhu C, Curran T, Xanthoudakis S, Prives C. Genes Dev. 1997;11:558–570. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.5.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Milne D M, Palmer R H, Meek D W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5565–5570. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.21.5565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Halazonetis T D, Kandil A N. EMBO J. 1993;12:5057–5064. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sturzbecher H W, Maniatis T, Chumakov P, Addison C, Simanis V, Rudge K, Philp R, Grimaldi M, Court W. Oncogene. 1990;5:781–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meek D W, Eckhart W. J Virol. 1990;64:1734–1744. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1734-1744.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee-Miller S P, Sakaguchi K, Ullrich S J, Appella E, Anderson C W. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:5041–5049. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.11.5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Addison C, Jenkins J R, Sturzbecher H W. Oncogene. 1990;5:423–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]