Abstract

The evolutionary dynamics existing between transposable elements (TEs) and their host genomes have been likened to an “arms race.” The selfish drive of TEs to replicate, in turn, elicits the evolution of host-mediated regulatory mechanisms aimed at repressing transpositional activity. It has been postulated that horizontal (cross-species) transfer may be one effective strategy by which TEs and other selfish genes can escape host-mediated silencing mechanisms over evolutionary time; however, to date, the most definitive evidence that TEs horizontally transfer between species has been limited to class II or DNA-type elements. Evidence that the more numerous and widely distributed retroelements may also be horizontally transferred between species has been more ambiguous. In this paper, we report definitive evidence for a recent horizontal transfer of the copia long terminal repeat retrotransposon between Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila willistoni.

Keywords: Drosophila, evolution

Long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons are a class of repetitive, mobile DNA sequences that transpose via the reverse transcription of an RNA intermediate. LTR retrotransposons are a primary source of spontaneous mutations that have major phenotypic effects (1) and are hypothesized to be of special evolutionary significance (2–4). Despite the fact that many LTR retrotransposons have been characterized, there have been few detailed studies on the naturally occurring variation existing among these elements within and between populations and species (5–8).

One outstanding issue concerning LTR retrotransposon evolution is the possibility of the horizontal transfer of elements between species. There is strong evidence that DNA elements have been transferred horizontally across species boundaries. The best examples of this are the P and mariner transposable elements of Drosophila (9, 10). Although evidence has been presented that LTR retrotransposons may have also experienced horizontal transfer in their evolution, these data have been less conclusive. This is largely because the suspected horizontal transfers occurred too long ago (11, 12) or between such closely related species (5) that alternative vertical transmission hypotheses cannot be completely eliminated. In this paper, we report that a copia LTR retrotransposon isolated from Drosophila willistoni is virtually identical in sequence to copia retrotransposons present within Drosophila melanogaster despite the fact that these two species have been separated from a common ancestor by ≈50 million years (13). Although copia is abundant in all melanogaster group species, it displays a patchy distribution in D. willistoni. Collectively, our findings indicate a recent horizontal transfer of the copia LTR retrotransposon from D. melanogaster to D. willistoni.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila Strains.

D. melanogaster Iquitos, Peru was provided by Jean R. David (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Gif-sur-Yvette, France). Chris Babcock and Margaret Kidwell (University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ) provided D. willistoni natural populations collected from Florida, Grenada, St. Vincent, and St. Croix. Drosophila simulans (Australia; #0251.4), D. willistoni (Royal Palm Park, Miami, FL; #0811.2), and D. willistoni (Santa Maria, de Ostuna, Nicaragua; #0811.0) were obtained from the National Drosophila Species Stock Center (Bowling Green, OH). The lab strain w1118 (U-85012) was obtained from the Umea Stock Center (Umea, Sweden). The Oregon R strain (B-2380) was obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center (Bloomington, IN).

PCR.

Genomic DNA was prepared from adult flies as described (14). The following primers were used in the PCRs. All copia and Adh primers were synthesized at the Molecular Genetics Instrumentation Facility at the University of Georgia (Athens, GA). Christian Schlotterer (University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, Austria) provided the rDNA primers.

Copia primers: Cop Ltr (5′-CTATTCAACCTACAAAAATAACG-3′), Cop Gag (5′-CCTTCTCTGCCACAGTGGTGACA-3′), Cop Pcs (5′-ATTACGTTTAGCCTTGTCCAT-3′), Cop XhoapaI (5′-CTCGAGGGGCCCAGTCCATGCCTAATA-3′).

Drosophila Adh primers: Adh-e2.1 (5′-CTGGACTTCTGGGACAAGCG-3′), Adh-e2.2 (5′-TGCAACATTGGATCCGTCACT-3′), Adh-i2 (5′-TTGTTTTTTCTTGAAAACTTTGCGTT-3′), Adh-e3 (5′-TAGATGCCCGAGTCCCAGTG-3′).

Drosophila rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) primers: CS249 (5′-TCGTAACAAGGTTTCCG-3′), CS 250 [5′-GTT (A/G) GTTTCTTTTCCTC-3′].

The following conditions were used in all PCR reactions: 1× PCR buffer (Fisher), 200 μM dNTPs (Pharmacia), 3 mM magnesium chloride (Fisher), 0.5 μM each primer, 2.5 units of Taq polymerase (Fisher), and 100 ng of genomic DNA. Thermal cycler conditions were as follows: 5 min at 94°C followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, 1 min at 72°C followed by a final 5 min at 72°C. The D. willistoni copia PCR product was then subcloned into pCR2.1 by using the TA cloning method (Invitrogen).

Southern Hybridization.

Genomic DNA was isolated as described (14). For each of the populations assayed, 5 μg of genomic DNA was digested to completion with EcoRI and ApaI according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega). Digested DNA was fractionated through 1% agarose gel and transferred to Hybond-N nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia). The membrane was prehybridized for 4 h at 66°C in 0.5 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.6, 7% SDS. A 5′ copia probe was generated with PCR by using the D. willistoni copia clone sequenced here as a template with primers XhoapaI and Cop Gag. The copia probe was labeled by using [32P]dATP (ICN) and the High Prime DNA Labeling Kit (Boehringer Mannheim). The probe was added to the prehybridization buffer and hybridization proceeded for 18 h at 66°C. The membrane was washed under the following high-stringency conditions: 10 min each at 64°C, 3 times the SSC, 0.1% SDS; 2× SSC, 0.1% SDS; 1× SSC, 0.1% SDS; and finally 0.1 × SSC, 0.1% SDS for 10 min at room temperature.

Genomic Library.

A genomic library was constructed from Royal Palm Park D. willistoni DNA. Approximately 2 μg of genomic DNA was partially digested with BamHI (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This DNA was then ligated into 1 μg of lambda arms of the replacement vector Lambda-DASH II (Stratagene).

The genomic library was screened by using a full-length copia element (Dm5002) as a probe. Supported nitrocellulose membranes (Schleicher & Schuell) containing plaque lifts were screened under the conditions described above. Plugs of isolated plaques were placed in 500 μl of SM. Lambda DNA was isolated by using the Qiagen (Chatsworth, CA) lambda kit.

Sequence Analysis.

Automated sequencing was done at the University of Georgia Molecular Genetics Instrumentation Facility (Athens, GA). The D. willistoni copia subclone was sequenced in both directions by using T7 and M13 reverse primers. The resulting chromatograms were aligned and compared by using the seqed program (Applied Biosystems) to resolve any sequence ambiguities. Copia sequences correspond to the following accession numbers: D. melanogaster c1-no. M11240, D. melanogaster c2-no. X04456, D. simulans c1-no. D10880, and D. willistoni c4-no. AF175766.

Results

Polymorphism for the Presence of Copia Exists Among Geographic Populations of D. willistoni.

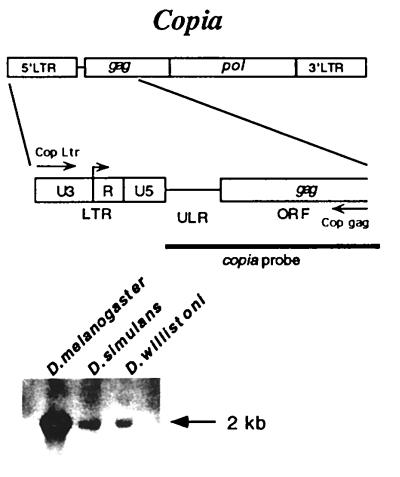

Copia is an LTR retrotransposon that is widely distributed among Drosophila species (12). Southern hybridization of D. willistoni with a copia probe under conditions of high stringency confirmed earlier reports (15) that the element is present in D. willistoni (Fig. 1). A Southern hybridization survey of recently established strains representing six populations of D. willistoni demonstrated that there is geographic polymorphism for the presence or absence of copia among D. willistoni (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Copia is an LTR retrotransposon. The genomic structure of copia consists of two LTRs that flank a single ORF with homology to the gag and pol loci of retroviruses. The 5′ region of copia was PCR amplified from D. willistoni genomic DNA by using the Cop Ltr and Cop gag primers. Southern hybridization of genomic DNA with a copia probe under conditions of high stringency confirmed the presence of copia in D. melanogaster, D. simulans, and D. willistoni.

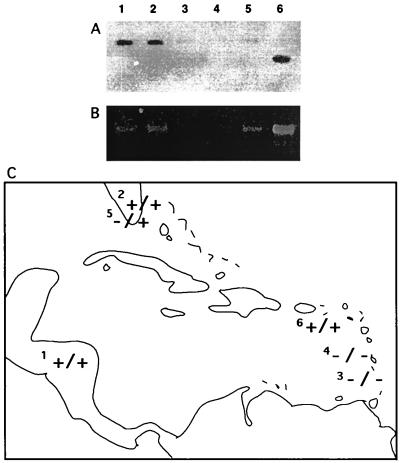

Figure 2.

Southern hybridization (A) and PCR (B) survey for the presence of copia in various D. willistoni populations: 1, Santa Maria, de Ostuna, Nicaragua; 2, Royal Palm Park; 3, Grenada; 4, St. Vincent, Grenadines; 5, South Florida; 6, St. Croix. We attribute the slightly smaller band in the St. Croix sample to a deletion within the copia gag region flanked by the ApaI–EcoRI restriction sites. The PCR results revealed no such intraspecific size polymorphism within the copia ITR–ULR. (C) The first + or − represents the results of Southern hybridization followed by the second + or − that represents PCR results.

PCR was also used to survey the above strains for the presence of copia. Primers that flank an ≈1-kb region of copia, which includes the 5′ LTR, the adjacent untranslated leader region (ULR) and gag encoding sequence, were used in an attempt to amplify copia sequences from D. willistoni genomic DNA (Fig. 1). The results of the PCR experiments were consistent with the Southern hybridization results in all cases except one (Fig. 2). PCR of genomic DNA from one of the South Florida strains that tested negative in our hybridization screen did nevertheless yield a copia PCR product. We interpret this observation to be the result of the high sensitivity of the PCR technique.

A Copia LTR Retrotransposon Isolated from a D. willistoni Florida Population Is >99% Identical to D. melanogaster Copia LTR Retrotransposons.

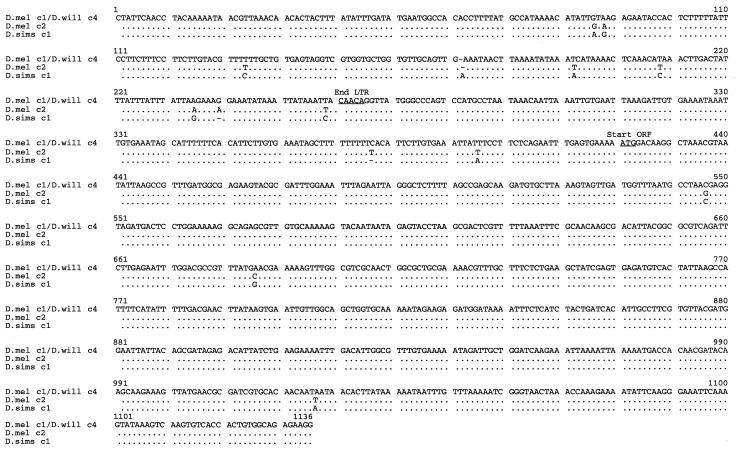

A copia PCR product isolated from the second South Florida population (Royal Palm Park) that tested positive for the presence of copia via both hybridization and PCR was subcloned and sequenced. Alignment of this D. willistoni copia sequence with published sequences of copia elements isolated from D. melanogaster and D. simulans demonstrated sequence similarities of >99% (Fig. 3). Previous results from a survey of melanogaster subgroup copia LTR-ULR variation revealed substantially lower sequence identities of ≈90% between copia sequences isolated from the sibling species D. melanogaster and D. simulans (5). Remarkably, the D. willistoni copia sequence isolated here was identical to that of a published D. melanogaster copia sequence (16) isolated in another laboratory. This identity of copia elements isolated from D. melanogaster and D. willistoni is particularly striking given the fact that these two species are estimated to have last shared a common ancestor ≈50 million years ago (13).

Figure 3.

Sequence alignment of the 5′ region of copia consisting of the 5′ LTR (1–265), ULR (266–430), and part of the gag locus (431–1,136) of the ORF. Dots in the alignment represent identity and dashes represent a gap in the sequence. The D. melanogaster no. M11240 (D. mel c1) and D. willistoni (Royal Palm Park; D. will c4) sequences are 100% identical. Polymorphic sites present in two other copia sequences isolated from D. melanogaster (D. mel c2) no. X04456 and D. simulans no. D10880 (D. sims c1) are shown below the D. mel c1/D. will c4 consensus sequence.

To eliminate the possibility that our results may have occurred because of contamination during the PCR process, we instituted a series of rigorous controls. Southern hybridization of D. willistoni DNA under conditions of high stringency eliminated the possibility that our PCR data result from contamination of our genomic DNA samples with a minute amount of copia-cloned sequence.

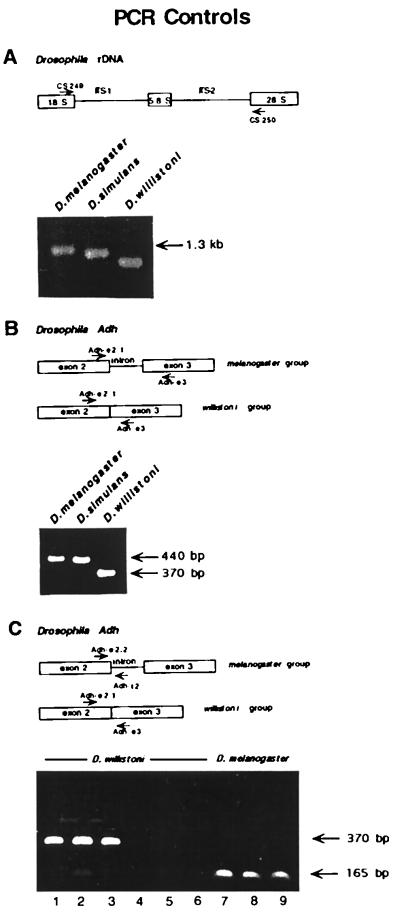

An additional series of PCR controls were performed to eliminate the possibility of contamination during the PCR process. Every PCR was performed with a double-distilled water negative-control template to guard against contamination of the PCR reagents. In the first series of internal PCR controls, primers that amplify the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of the multicopy Drosophila rDNA genes were employed. ITS regions are variable and show species-specific size polymorphisms (17). Primers homologous to highly conserved sequences within the 18S and 28S rDNA coding regions that flank the ITS-1, 5.8S rDNA and ITS-2 regions were used to amplify genomic DNA from D. melanogaster and D. simulans as well as that from the D. willistoni sample (Royal Palm Park) from which we amplified the copia sequence. Each species sample resulted in PCR products of unique size (Fig. 4). No evidence of contamination was found in any of these reactions despite the fact that we separately established, by using intentional contamination of genomic DNA samples, that as little as 100 pg of contaminating D. melanogaster DNA could be detected in our assays.

Figure 4.

PCR contamination controls. (A) Primers CS 249 and CS 250 were used to PCR amplify genomic DNA representing D. melanogaster (Iquitos), D. simulans (Australia), and D. willistoni (Royal Palm Park) populations. Each species showed ITS PCR products of unique size with no evidence of contamination. (B) Primers Adh-e2.1; Adh-e2.2; and Adh-e3 were used to PCR amplify genomic DNA from the same DNA samples used in (A). PCR of D. willistoni (Royal Palm Park) genomic DNA resulted in only the smaller Adh product with no evidence of DNA contamination from any of the melanogaster group species. (C). Primer Adh-e2.1 and Adh-e3 were used to PCR amplify 10 ng of D. willistoni genomic DNA representing the Royal Palm Park (lane 1), Santa Maria, de Ostuna, Nicaragua (lane 2), and South Florida (lane 3) populations. Primer Adh-e2.2 is homologous to a region of the D. melanogaster Adh gene located ≈65 bp 5′ of the second intron. Adh-e2.2 differs from the homologous D. willistoni sequence in its 3′ end rendering it incapable of amplifying the D. willistoni Adh gene. The D. melanogaster-specific primers Adh-e2.2 and Adh-i2 were used in an effort to amplify a product from 200 ng of the same D. willistoni genomic DNA samples used to generate the products depicted in lanes 1–3. The results (lanes 4–6) demonstrate that there is no contaminating D. melanogaster DNA in the D. willistoni samples. The D. melanogaster-specific primers Adh-2.2 and Adh-i2 were used to PCR amplify 5 ng of genomic DNA representing two D. melanogaster lab strains, w1118 (lane 7) and Oregon R (lane 8) and a strain representing the D. melanogaster (Iquitos) population (lane 9).

A second series of internal PCR controls utilized primers homologous to sequences within the Drosophila alcohol dehydrogenase gene (Adh). Adh genes present in melanogaster group species contain two introns, the second of which is missing in willistoni group species (18). In our control experiments, we utilized primers homologous to conserved sequences within the second and third exons of Drosophila Adh. PCR products obtained by using melanogaster group species DNA as a template are predicted to be ≈70 bp larger than those obtained by using willistoni group species DNA as a template because of the missing intron in D. willistoni Adh. Consistent with our previous controls, the D. willistoni genomic DNA sample resulted in only the smaller Adh product with no evidence of DNA contamination from any of the melanogaster group species (Fig. 4).

To further ensure that the D. willistoni genomic DNA preparations were free from contaminating D. melanogaster DNA, we performed a final PCR control utilizing primers homologous to sequences in the second exon and second intron of the D. melanogaster Adh gene. The second exon primer was designed with two polymorphisms at the 3′ end unique to D. melanogaster Adh. The second intron primer is homologous only to D. melanogaster Adh sequences because this intron is missing in the D. willistoni Adh gene; therefore, this primer pair can only amplify an Adh product from D. melanogaster DNA and not D. willistoni DNA. This primer pair was able to amplify a product of the expected size from as little as 5 ng of D. melanogaster genomic DNA. Samples of D. willistoni DNA up to 200 ng did not yield any PCR product by using the same primers; thus, the results of this control experiment also indicate that the D. willistoni DNA preparations do not contain any contaminating D. melanogaster genomic DNA.

As a final control to eliminate any possibility that our results are attributable to contamination during the PCR process, we isolated and partially sequenced a copia positive clone from a D. willistoni genomic library. This library was constructed by using DNA isolated from flies representing the Royal Palm Park population. The 441-bp LTR-ULR sequence contained within the D. willistoni genomic clone is 99.5% identical to that of the D. willistoni copia PCR product described above. Based on these controls, we conclude that the sequence identity between the D. willistoni and D. melanogaster copia elements reported here is not an artifact of experimental contamination.

Discussion

The coding regions of the highly conserved Adh genes of D. willistoni and D. melanogaster display less than 80% sequence identity, which reflects the fact that these two species diverged from a common ancestor ≈50 million years ago (19). It seems unlikely that 100% sequence identity could be selectively or otherwise maintained between retrotransposons separated from a common ancestor for this length of time; moreover, the LTR and ULR are noncoding regions that are expected to evolve even more rapidly than coding regions of the element. Previous surveys of LTR sequence variation among other retrotransposon families indicate that high levels of divergence often exist both within and between host species (20); thus, the most reasonable explanation for our results is that copia has been horizontally transferred between D. willistoni and D. melanogaster in the recent evolutionary past.

D. willistoni is a New World species with a distribution from South America north through Mexico, the Caribbean Islands, and Florida. Because D. melanogaster is a cosmopolitan species with a range overlapping that of D. willistoni, the physical opportunity for horizontal transfer between these two species exists; however, because D. melanogaster, which originated in Africa, has become cosmopolitan in the last 100–200 years (21), there has been only a recent window of opportunity for direct horizontal transfer between these two species. A well-documented horizontal transfer of a P element is believed to have occurred from D. willistoni to D. melanogaster within this short time frame (9). The fact that copia is abundant and widespread among D. melanogaster subgroup species but scarce with patchy distribution in D. willistoni suggests that the direction of transfer of copia was from D. melanogaster to D. willistoni.

The mechanism by which horizontal transfers occur remains obscure; however, there is circumstantial evidence suggesting that parasitic mites may be involved in vectoring DNA between Drosophila species (22). In addition, transmission by insect viruses is another likely mechanism by which transposable elements may be vectored between species (23).

Studies addressing the molecular evolution of transposable elements often yield data that appear consistent with the hypothesis of horizontal transfer. As stated above, there is particularly strong evidence indicating that DNA-type elements (P and mariner) have crossed species boundaries via horizontal transfer (9, 24, 25). Although previous reports have also suggested that LTR retrotransposons may horizontally transfer across species boundaries (8, 9, 23, 24), this evidence has been less definitive (7, 26). Our finding that copia elements isolated from two distantly related Drosophila species are sequentially identical seems inconsistent with any model of vertical transmission.

It has been postulated that cross-species transfers may be an effective strategy by which DNA-type transposable elements escape inactivation over evolutionary time (27, 28). Because copia and other LTR retrotransposons are known to be subject to effective host-mediated repression (6, 14), it is likely that significant selective pressure exists to favor horizontal transfer of LTR retrotransposons as well. There is a growing body of evidence that retrotransposons play a major role in eukaryotic genome organization and evolution (2–4, 29–33). If the horizontal transfer of LTR retrotransposons is found to be widespread, the evolutionary consequences could be significant.

Abbreviations

- TE

transposable element

- LTR

long terminal repeat

- ULR

untranslated leader region

- ITS

internal transcribed spacer

- Adh

alcohol dehydrogenase gene

Footnotes

References

- 1.Berg D E, Howe M M. Mobile DNA. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald J F. Trends Ecol Evol. 1995;10:123–126. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(00)89012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wessler S R, Bureau T E, White S E. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:814–821. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller W J, Kruckenhauser L, Pinsker W. In: Transgenic Organisms—Biological and Social Implications. Tomiuk J, Woerhm K, Sentker A, editors. Basel: Birkhauser; 1996. pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan I K, McDonald J F. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:1160–1171. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vernhettes S, Grandbastien M A, Casacuberta J M. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;36:429–447. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.VanderWiel P L, Voytas D F, Wendel J F. J Mol Evol. 1993;36:429–447. doi: 10.1007/BF02406720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flavell A J, Smith D B, Kumar A. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;231:233–242. doi: 10.1007/BF00279796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels S B, Peterson K R, Strausbaugh L D, Kidwell M G, Chovnick A. Genetics. 1990;124:339–355. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.2.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson H M, Lampe D J. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:850–862. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flavell A J. Genetica (The Hague) 1992;86:203–214. doi: 10.1007/BF00133721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alberola T M, de Frutos R. J Mol Evol. 1993;36:127–135. doi: 10.1007/BF00166248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beverley S M, Wilson A C. J Mol Evol. 1984;21:1–13. doi: 10.1007/BF02100622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matyunina L V, Jordan I K, McDonald J F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7097–7102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stacey S N, Lansman R A, Brock H W, Grigliatti T A. Mol Biol Evol. 1986;3:522–534. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mount S M, Rubin G M. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:1630–1638. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.7.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schlotterer C, Hauser M T, von Haeseler A, Tautz D. Mol Biol Evol. 1994;11:513–522. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson C L, Carew E A, Powell J R. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:605–618. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russo C A, Takezaki N, Nei M. Mol Biol Evol. 1995;12:391–404. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arkhipova I R, Lyubomirskaya N V, Ilyin Y V. Drosophila Retrotransposons. Austin, TX: R. G. Landes Company; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.David J P, Capy P. Trends Genet. 1988;4:106–111. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(88)90098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houck M A, Clark J B, Peterson K R, Kidwell M G. Science. 1991;253:1125–1128. doi: 10.1126/science.1653453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller D W, Miller L K. Nature (London) 1982;299:562–564. doi: 10.1038/299562a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson H M. Nature (London) 1993;362:241–245. doi: 10.1038/362241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hagemann S, Haring E, Pinsker W. Genetica (The Hague) 1996;98:43–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00120217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doolittle R F, Feng D F, Johnson M S, McClure M A. Q Rev Biol. 1989;64:1–30. doi: 10.1086/416128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizrokhi L J, Mazo A M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9216–9220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capy P, Anxolabehere D, Langin T. Trends Genet. 1994;10:7–12. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maruyama K, Hartl D L. J Mol Evol. 1991;33:514–524. doi: 10.1007/BF02102804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurst G D, Hurst L D, Majerus M E. Nature (London) 1992;356:659–660. doi: 10.1038/356659a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald J F. Trends Ecol Evol. 1998;13:94–95. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(97)01282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levis R W, Ganesan R, Houtchens K, Tolar L A, Sheen F M. Cell. 1993;75:1083–1093. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90318-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.SanMiguel P, Tikhonov A, Jin Y K, Motchoulskaia N, Zakharov D, Melake-Berhan A, Springer P S, Edwards K J, Lee M, Avramova Z, et al. Science. 1996;274:765–768. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Neill R J W, O’Neill M J, Graves J A M. Nature (London) 1998;393:68–72. doi: 10.1038/29985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moran J V, DeBerardinis R J, Kazazian H H. Science. 1999;283:1530–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]