Abstract

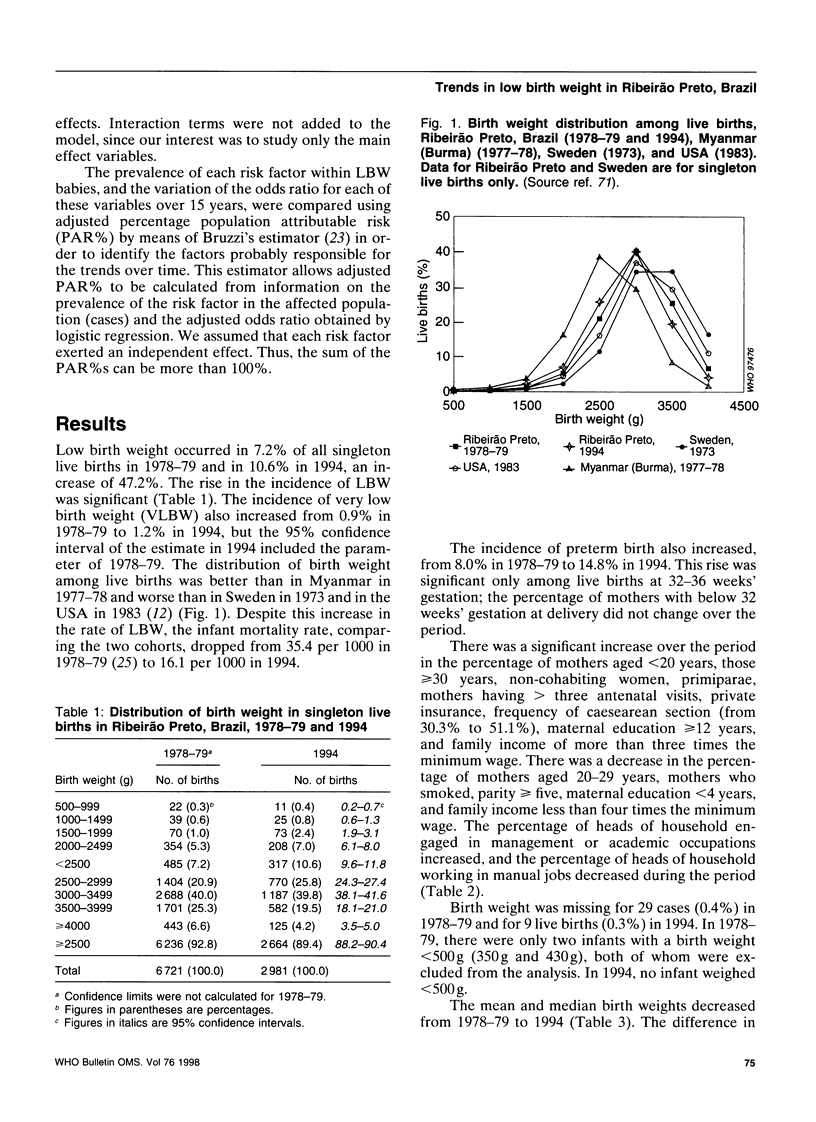

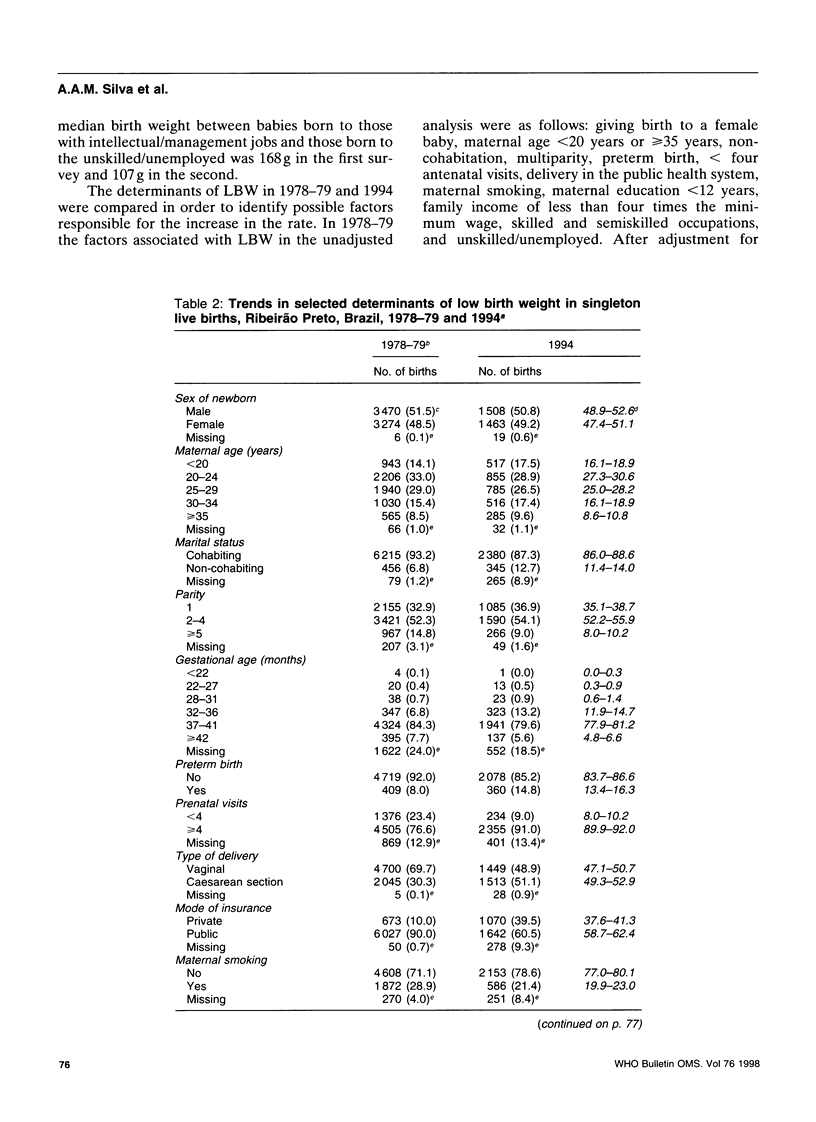

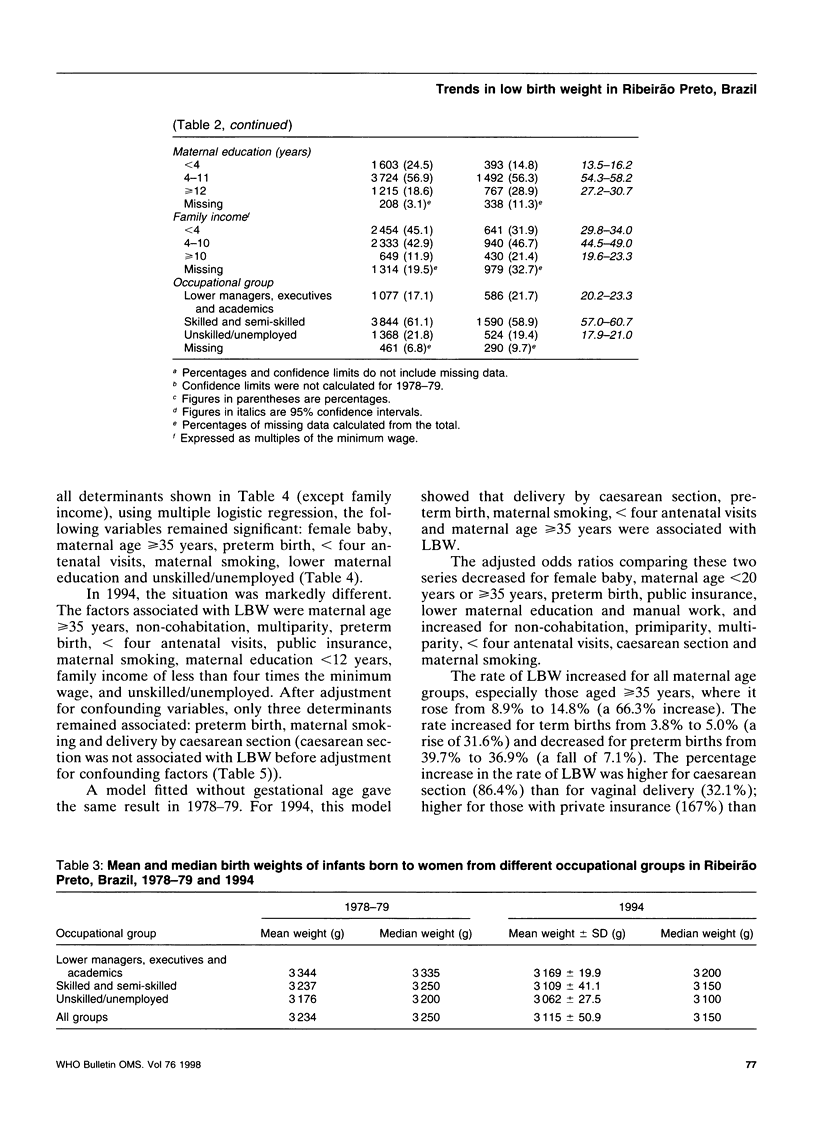

The incidence and some determinants of low birth weight (LBW) were studied in two population-based cohorts of singletons born live to families in Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo State, Brazil. The first cohort comprised infants born between June 1978 and May 1979 (6750 births--population survey) and the second, infants born between May and August 1994 (2990 births--sample survey). The incidence of LBW was 7.2% in 1978-79 and 10.6% in 1994. After adjustment for confounding factors, the following determinants remained significant in 1978-79: female sex, maternal age > or = 35 years, preterm delivery, < four antenatal health visits, maternal smoking, lower level of maternal education, and manual work/unemployment. In 1994, the significant determinants were preterm delivery, maternal smoking and caesarean section. The adjusted percentage population attributable risk (PAR%) fell for the majority of risk factors but increased for caesarean section, preterm birth, multiparity (> or = 5), primiparity and non-cohabitation. The increase in the rate of LBW from 1978-79 to 1994 was higher for families with more qualified occupations, and occurred only for infants delivered at 36-40 weeks' gestational age and weighing 1500-2499 g, i.e. those most likely to be born by elective caesarean section. The caesarean section rate rose from 30.3% in 1978-79 to 51.1% in 1994. The increase in LBW was probably due to iatrogenic practices associated with elective caesarean section.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alberman E. Are our babies becoming bigger? J R Soc Med. 1991 May;84(5):257–260. doi: 10.1177/014107689108400505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberman E., Botting B. Trends in prevalence and survival of very low birthweight infants, England and Wales: 1983-7. Arch Dis Child. 1991 Nov;66(11):1304–1308. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.11.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander S., Boutsen M., Kittel F., Buekens P. Les taux d'insuffisance pondérale à la naissance en Europe: problèmes d'enregistrement et effets des interventions médicales. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1995;43(3):272–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonisamy B., Rao P. S., Sivaram M. Changing scenario of birthweight in south India. Indian Pediatr. 1994 Aug;31(8):931–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros F. C., Victora C. G., Vaughan J. P., Jair Estanislau H. Bajo peso al nacer en el municipio de Pelotas, Brasil: factores de riesgo. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam. 1987 Jun;102(6):541–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra J. E., Atrash H. K., Pérez N., Saliceti J. A. Low birthweight and infant mortality in Puerto Rico. Am J Public Health. 1993 Nov;83(11):1572–1576. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.11.1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzzi P., Green S. B., Byar D. P., Brinton L. A., Schairer C. Estimating the population attributable risk for multiple risk factors using case-control data. Am J Epidemiol. 1985 Nov;122(5):904–914. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzezinski Z. J., Szamotulska K. The widening gap in low birthweight rates between extreme social groups in Poland during 1985-90. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1994 Oct;8(4):373–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1994.tb00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David R. J. Did low birthweight among US blacks really increase? Am J Public Health. 1986 Apr;76(4):380–384. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.4.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson A., Eriksson M., Källén B., Zetterström R. Secular trends in the effect of socio-economic factors on birth weight and infant survival in Sweden. Scand J Soc Med. 1993 Mar;21(1):10–16. doi: 10.1177/140349489302100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton A. C., Field D. J., Mason E., Clarke M. Attitudes to viability of preterm infants and their effect on figures for perinatal mortality. BMJ. 1990 Feb 17;300(6722):434–436. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6722.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourbin G., Masuy-Stroobant G. Registration of vital data: are live births and stillbirths comparable all over Europe? Bull World Health Organ. 1995;73(4):449–460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibe B. C. Low birth weight (LBW) and structural adjustment programme in Nigeria. J Trop Pediatr. 1993 Oct;39(5):312–313. doi: 10.1093/tropej/39.5.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M. S. Determinants of low birth weight: methodological assessment and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65(5):663–737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick M. C. The contribution of low birth weight to infant mortality and childhood morbidity. N Engl J Med. 1985 Jan 10;312(2):82–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501103120204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mock N. B., Mercer D. M., Setzer J. C., Magnani R. J., Tankari K., Brown L. Prevalence and differentials of low birth weight in Niamey, Niger. J Trop Pediatr. 1994 Apr;40(2):72–77. doi: 10.1093/tropej/40.2.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsën P., Lärä E., Rantakallio P., Järvelin M. R., Sarpola A., Hartikainen A. L. Epidemiology of preterm delivery in two birth cohorts with an interval of 20 years. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Dec 1;142(11):1184–1193. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power C. National trends in birth weight: implications for future adult disease. BMJ. 1994 May 14;308(6939):1270–1271. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6939.1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez C., Regidor E., Gutiérrez-Fisac J. L. Low birth weight in Spain associated with sociodemographic factors. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995 Feb;49(1):38–42. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepkowitz S. Why infant very low birthweight rates have failed to decline in the United States vital statistics. Int J Epidemiol. 1994 Apr;23(2):321–326. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teruel J. R., Gomes U. A., Nogueira J. L. Investigacion interamericana de mortalidad en la niñez: peso al nacer en la region de Ribeirão Prêto, São aulo, Brasil. Bol Oficina Sanit Panam. 1975 Aug;79(2):139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox A., Skjaerven R., Buekens P., Kiely J. Birth weight and perinatal mortality. A comparison of the United States and Norway. JAMA. 1995 Mar 1;273(9):709–711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva A. A., Barbieri M. A., Bettiol H., Dal Bó C. M., Mucillo G., Gomes U. A. Saúde perinatal: baixo peso e classe social. Rev Saude Publica. 1991 Apr;25(2):87–95. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89101991000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva A. A., Gomes U. A., Bettiol H., Dal Bo C. M., Mucillo G., Barbieri M. A. Associaço entre idade, classe social e hábito de fumar maternos com peso ao nascer. Rev Saude Publica. 1992 Jun;26(3):150–154. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89101992000300004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]