Abstract

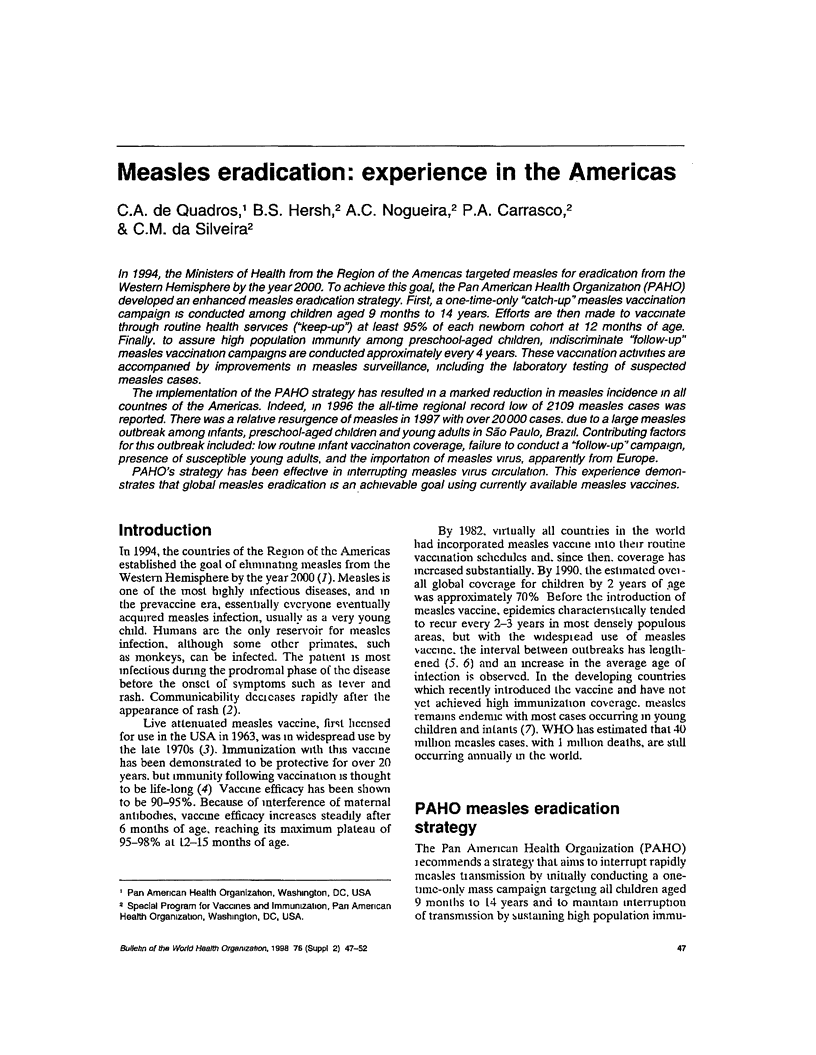

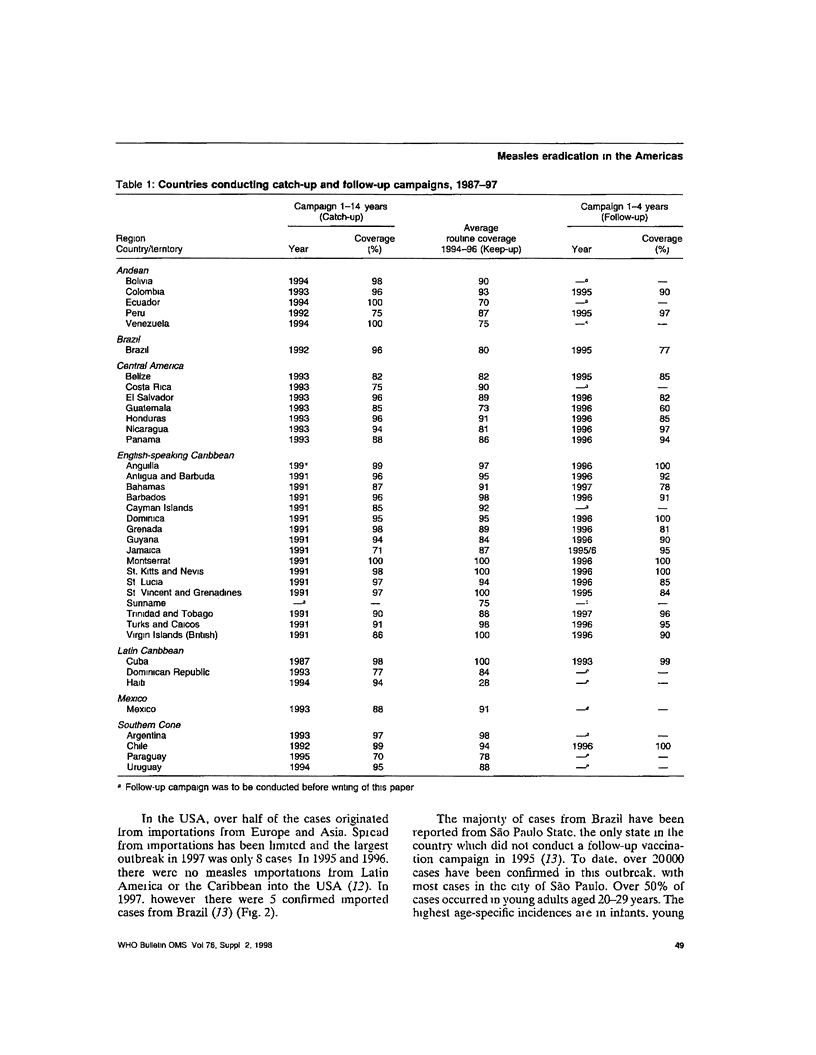

In 1994, the Ministers of Health from the Region of the Americas targeted measles for eradication from the Western Hemisphere by the year 2000. To achieve this goal, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) developed an enhanced measles eradication strategy. First, a one-time-only "catch-up" measles vaccination campaign is conducted among children aged 9 months to 14 years. Efforts are then made to vaccinate through routine health services ("keep-up") at least 95% of each newborn cohort at 12 months of age. Finally, to assure high population immunity among preschool-aged children, indiscriminate "follow-up" measles vaccination campaigns are conducted approximately every 4 years. These vaccination activities are accompanied by improvements in measles surveillance, including the laboratory testing of suspected measles cases. The implementation of the PAHO strategy has resulted in a marked reduction in measles incidence in all countries of the Americas. Indeed, in 1996 the all-time regional record low of 2109 measles cases was reported. There was a relative resurgence of measles in 1997 with over 20,000 cases, due to a large measles outbreak among infants, preschool-aged children and young adults in São Paulo, Brazil. Contributing factors for this outbreak included: low routine infant vaccination coverage, failure to conduct a "follow-up" campaign, presence of susceptible young adults, and the importation of measles virus, apparently from Europe. PAHO's strategy has been effective in interrupting measles virus circulation. This experience demonstrates that global measles eradication is an achievable goal using currently available measles vaccines.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Measles--United States, 1996, and the interruption of indigenous transmission. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997 Mar 21;46(11):242–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements C. J., Strassburg M., Cutts F. T., Torel C. The epidemiology of measles. World Health Stat Q. 1992;45(2-3):285–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine P. E., Clarkson J. A. Measles in England and Wales--I: An analysis of factors underlying seasonal patterns. Int J Epidemiol. 1982 Mar;11(1):5–14. doi: 10.1093/ije/11.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospedales C. J. Update on elimination of measles in the Caribbean. West Indian Med J. 1992 Mar;41(1):43–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRUGMAN S., GILES J. P., JACOBS A. M., FRIEDMAN H. Studies with a further attenuated live measles-virus vaccine. Pediatrics. 1963 Jun;31:919–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean A. R., Anderson R. M. Measles in developing countries. Part I. Epidemiological parameters and patterns. Epidemiol Infect. 1988 Feb;100(1):111–133. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800065614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Quadros C. A., Olivé J. M., Hersh B. S., Strassburg M. A., Henderson D. A., Brandling-Bennett D., Alleyne G. A. Measles elimination in the Americas. Evolving strategies. JAMA. 1996 Jan 17;275(3):224–229. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]