Abstract

Background

Smoking cessation programs are very effective, but little is known about how to get smokers to attend these programs.

Objective

To evaluate whether an “on-call” counselor increased smoking cessation program referrals and attendance.

Design

We randomly assigned 1 of 2 primary care teams at the Sepulveda VA Ambulatory Care Center to intervention and the other to usual care. The intervention team had access to an on-call counselor who provided counseling and care coordination. Social marketing efforts included educational outreach, provider feedback, and financial incentives.

Measurements

Baseline telephone interviews with a sample of 482 smokers were conducted, covering smoking history, health status, and smoking cessation treatments. Follow-up surveys were conducted at mid-intervention (n = 251) and post-intervention (n = 251).

Results

Two hundred ninety-six patients were referred to the on-call counselor, who counseled each patient in person and provided follow-up calls. The counselor referred 45% to the on-site program, and 27% to telephone counseling; of these, half followed through on the referral; 28% declined referral. Patients on the intervention team were more likely to report being counseled about smoking (68% vs 56%; odds ratio [OR] 1.7, CI 1.0–2.9) and referred to a cessation program (38% vs 23%; OR 2.1, CI 1.2–3.6); having attended the program (11% vs 4%; OR 3.6, CI 1.2–10.5); and receiving a prescription for bupropion (17% vs 8%) (OR 2.3, CI 1.1–5.1). The effect was not sustained after the case management period.

Conclusions

Having access to an on-call counselor with case management increased rates of smoking cessation counseling, referral, and treatment. The intervention could be reproduced by other health care systems.

KEY WORDS: smoking cessation, counseling, incentives, provider behavior, referral

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE

Tobacco cessation is rated as a top priority for health care systems1 and many effective treatments exist,2,3 yet these treatments are still infrequently used. Zhu et al. (2000) found that only 20% of smokers used any form of assistance (medications, counseling, or self-help materials) with their quit attempt.4 Within the VA, only about 7–10% of smokers received medications in the prior year although about 60% tried to quit.2,5

Despite most smokers being interested in quitting,5 few are referred to smoking cessation programs and only a minority of those referred actually attends the program. In a recent survey of VA patients, Sherman et al. 6 found that although 45% of smokers tried to quit in the prior year, only 28% reported being referred to a smoking cessation program and only 9% actually attended the program.

In a review of group tobacco counseling programs, the reported rate of program attendance was quite variable, but usually very low.7 In-person smoking cessation programs are available at nearly every VA site8 and elsewhere. Telephone Quitlines are very effective9 and widely available. These programs have been shown to be the most effective and the most cost-effective.10,11

The current Public Health Service (PHS) guidelines for tobacco cessation offer evidence-based approaches for providers and health care organizations.3 The guidelines recommend a “5A” structure of care delivery model for smoking cessation, including asking about tobacco use, advising smokers to quit, assessing each smoker’s level of interest in quitting, and offering appropriate interventions and follow-up. Alternatively, many experts think a more feasible approach is to ask about tobacco use, advise smokers to quit, and then refer for additional treatment.

Although many experts now favor the Ask–Advise–Refer approach, few studies have examined how to get smokers to attend smoking cessation programs. We tested whether access to an “on-call” counselor in conjunction with case management is effective in increasing use of smoking cessation treatment.

DESIGN

Study Setting

This study took place at the Sepulveda Ambulatory Care Center (ACC), an urban/suburban VA site in Los Angeles. It was approved by the VA and UCLA Institutional Review Boards. The approximately 20,000 patients assigned to the Sepulveda ACC are assigned to 2 primary care teams of about 60 providers each.12,13 Smoking prevalence is 29%, very similar to the 30% prevalence seen among VA users nationwide.5

During the study period, all providers used an electronic medical record,14,15 which included clinical reminders for tobacco use.15 Smoking cessation has been a nationally mandated VA guideline since 1996, with facilities held accountable for screening and advising rates.15,16

Sepulveda has an active Smoking Cessation Clinic (SCC),17 providing pharmacotherapy and interdisciplinary counseling during 6–7 visits over 2 months. The SCC uses a problem-solving therapy approach, counseling individual patients sequentially in an open, group setting. Participants are strongly encouraged to use medications (nicotine patches and/or bupropion) to help them quit. During the period of our intervention, smoking cessation medications were only available to patients using the SCC or the intervention, as VA primary care providers were not authorized to prescribe smoking cessation medications (this policy has since been reversed).

Intervention

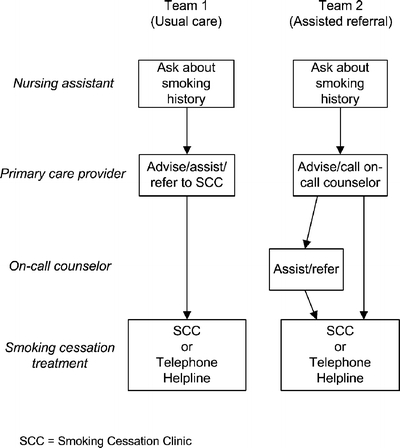

The study design is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of study intervention on the 2 primary care teams. SCC = Smoking Cessation Clinic.

One primary care team was randomly assigned by coin flip to receive the intervention, whereas the other received usual care. The intervention consisted of 4 components:

On-call counselor—During clinic hours, providers on the intervention team providers could page a trained counselor, who would come to the clinic within 5 minutes and provide 10–15 minutes of detailed smoking cessation counseling. Treatment options were explained, and the patient could then choose to be referred to a program, or choose not to be referred at all. The counselor handled all necessary documentation, such as referral to a smoking cessation program (either the Sepulveda SCC or the California Smokers’ Helpline, a free service of the California Department of Health18) and responding to the smoking cessation clinical reminders.

Case management—The counselor followed all referred patients for 2 months, calling them at 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks. The calls lasted 5–15 minutes and utilized the same problem-solving therapy approach used in the Sepulveda SCC. At each call, patients who had not yet acted on a referral were given encouragement and assisted with problem-solving regarding quitting. If patients were not willing or able to go to a smoking cessation program, they were also given the option of receiving all follow-up smoking cessation care from the counselor by telephone.

Medication management—Patients attending the Sepulveda SCC received medications through the clinic as part of the program. For all other patients receiving case management, the counselor coordinated the dispensing of smoking cessation medications. One of the study team (SES) prescribed medications for all patients receiving telephone counseling.

- Social marketing—We also used a wide range of strategies to modify provider behavior19 on the intervention team, including:

- Educational outreach—The project director and both on-call counselors (IA, ME) performed individual educational outreach (or academic detailing) visits22,23 with each provider monthly for the first 3 months. At each visit, the counselors (1) reintroduced themselves, (2) asked if there were any problems with the project, (3) encouraged them to refer as many patients as possible, and (4) offered them candy.

- Provider profiling—Each week, we posted a color bar graph with the number of patients referred by each provider.24 Because referral was optional and the results were not used in any punitive way, the bar graph listed each provider by name.

- Financial incentives25—At the end of each month, we publicly presented a $25 gift certificate to the provider who referred the most patients.

MEASUREMENTS

Evaluation

Our primary outcome was whether patients on the intervention team received more smoking cessation treatment (counseling, medications, and referral) than patients on the control team. To assess this, we enrolled a population-based sample of smokers from each team who used the primary care clinic regularly, and followed the cohort over time.

For the initial interview, we identified all patients who had had at least 3 primary care visits in the prior year and thus had a reasonable chance to be exposed to the intervention. We excluded patients who had 10+ mental health visits during that time and patients who did not have a phone. Using computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI), we then screened all patients. The screening procedure is nearly identical to what we have described elsewhere for a previous study.26 This sampling strategy was unrelated to whether the patients had received the on-call counseling intervention.

Patients were first asked if they smoke, and current smokers were asked to give verbal informed consent for a detailed interview. The CATI system allowed the interviewers to enter data directly into the computer and performed concurrent error checking, thus greatly decreasing the amount of missing or bad data.

The initial interviews were conducted just before the start of the 12-month intervention. Our plan was to follow the cohort of smokers again with telephone interviews at 6, 12, and 18 months, with patients receiving a $10 incentive after each interview. However, because of budget constraints we had to use mailed surveys instead of telephone surveys for follow-up contacts, and because of administrative delays in processing patient incentives, there was a much broader spread than planned in the follow-up contacts. Survey questionnaires were mailed to each patient at 6–11 months (“mid-intervention”) and at 12–18 months (“post-intervention”) after his or her last interview or survey. The CATI software scheduled each patient’s follow-ups based on his/her last interview or mailed survey, so there was always at least 5–6 months between contacts.

Evaluation Sample

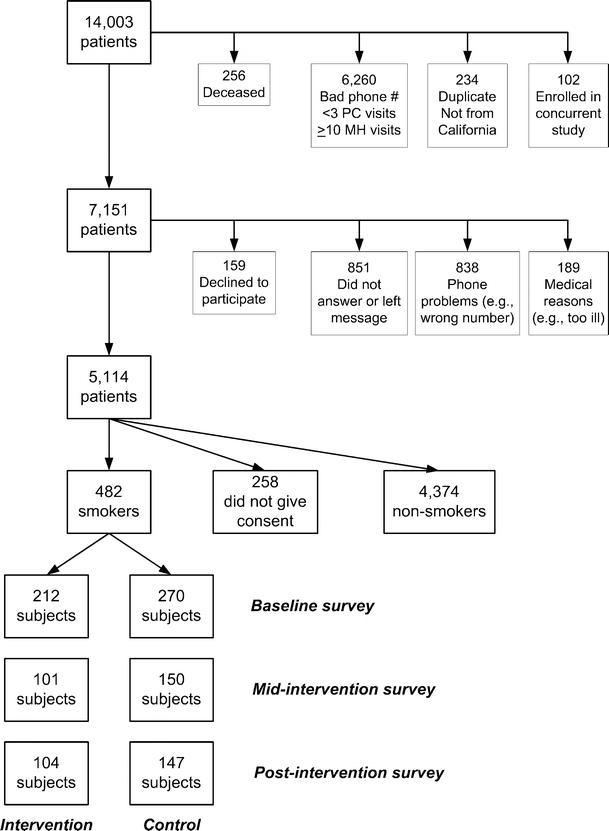

Our sample is shown in Figure 2. We used data from the VA Outpatient File (VA Austin Automation Center) to obtain a list of all patients seen within primary care during the previous 18 months at the Sepulveda Ambulatory Care Center (14,003 patients). Of the 7,151 eligible to participate whom we tried to contact, 482 were smokers who consented to participate, constituting our baseline sample.

Figure 2.

Sampling diagram for population-based survey to evaluate intervention.

Our intervention sample consisted of 212 patients assigned to the intervention team. The control sample consisted of 270 patients representing patients from all clinics other than the intervention team clinic. The control sample included patients assigned to the control team (n = 226), patients assigned to other sites for primary care who came to Sepulveda occasionally (n = 21), and a small number of patients receiving primary care through Sepulveda’s other clinics: Women’s Health Program (n = 14), Geriatrics (n = 8), and the Spinal Cord Injury (n = 1). At mid-intervention follow-up, we received completed surveys from 251 subjects (101 intervention [48% response], 150 control [56% response]). At post-intervention follow-up, we again received completed surveys from 251 subjects (104 intervention [49% response], 147 control [54% response]).

Survey Content

The baseline survey is summarized in Table 1. The 30-minute, 134-item survey was very similar to one we have used previously.7

Table 1.

Baseline Survey Components and Sources

| Domain | Areas of assessment | Source(s) of questions |

|---|---|---|

| Tobacco use and quit attempts | Smoking history | Adapted from the California Tobacco Survey27 |

| Attitude toward smoking | ||

| Interest in quitting | ||

| Process of care for smoking cessation | Provider counseled patient to stop smoking in past 12 months | Adapted from an earlier survey12 |

| Provider offered medications to help quit | ||

| Receipt of smoking cessation medications | ||

| Provider referral to in-person or telephone smoking cessation program | ||

| Use of smoking cessation program | ||

| Health status | Self-reported health status | Adapted from the 12-item SF-12 V, a version of the SF-12 specifically for VA users28 |

| Physical functioning | ||

| Mental functioning | ||

| Medical comorbidity | Pulmonary conditions | Adapted from the Medical Outcomes Study and other sources12,29 |

| Living arrangements and demographics | Whether patient lived with family and friends | Adapted from the California Tobacco Survey27 and other sources30; demographic questions derived from an earlier survey12 |

| Rules about smoking in the home | ||

| Education level | ||

| Employment status | ||

| Income |

The follow-up surveys (conducted by mail) were shorter versions of the baseline survey, with the only change being that patients were asked about the previous 6 months instead of the previous 12 months. Patients were considered nonsmokers at follow-up if they reported not smoking any cigarettes in the prior 30 days. No attempt was made to validate their self-report, as respondents were not participating in a smoking cessation intervention.

Analysis

Our primary outcome was whether smokers on the intervention team received more smoking cessation treatment than control team patients. Because in-person smoking cessation clinics are considered the gold standard of treatment, we used smoking cessation clinic attendance for our power calculation. We did not do a power calculation for abstinence rates because our goal was simply to get more patients into effective treatment, based on the assumption that it would lead to more people actually quitting smoking.

Our a priori power calculation called for a cohort of 330 patients on each team at follow-up to have an 80% chance of finding a 75% increase in smoking cessation clinic attendance rate (from 10% to 17.5%). We initially used chi-square tests and analysis of variance to compare patients on the intervention team with patients on the control team. We then refined the analysis, using logistic regression to adjust for both baseline differences and time to follow-up. We also used chi-square tests to compare whether each team changed from baseline to mid-intervention and from mid-intervention to post-intervention.

RESULTS

During the year-long study period, the counselors received 296 referrals from 62 providers on the intervention team (range of referrals 1–29). Referrals by the counselors were made entirely based on patient preference. Of the 296 referrals to an on-call counselor, 133 (45%) were referred to the in-person smoking cessation program, 23 (8%) were referred to the California Smokers Helpline, 58 (20%) received telephone management solely from the counselor, and 82 (28%) chose not to be referred.

Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of our evaluation cohort. Patients on the intervention team were more likely to have ever tried to quit smoking and to have quit for at least 1 day in the last year. They were less likely than patients on the control team to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Smokers on the Intervention and Control Teams*

| Intervention n = 212 (%) | Control n = 270 (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian | 77 | 74 | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| Currently married | 34 | 33 | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) |

| Income ≤ $20,000 | 63 | 65 | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) |

| Ever try to quit smoking | 91 | 80 | 2.4 (1.4–4.2) |

| Ever use other types of tobacco | 58 | 49 | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) |

| History of COPD† | 18 | 31 | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) |

| Current health—Excellent/very good | 22 | 18 | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) |

| In the last 12 months... | |||

| Quit for ≥ 1 day | 44 | 34 | 1.5 (1.1–2.2) |

| Provider talked about smoking | 72 | 68 | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| Nicotine patch prescribed | 25 | 27 | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) |

| Bupropion prescribed | 15 | 16 | 0.8 (0.5–1.5) |

| Referred to smoking cessation program | 35 | 31 | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| Attended smoking cessation program | 12 | 9 | 1.3 (0.7–2.4) |

| Referred to Quitline telephone counseling | 0.9 | 3.7 | 0.2 (0.1–1.1) |

| Received Quitline telephone counseling | 0.5 | 0 | – |

*At baseline, we enrolled a population-based cohort of patients from each primary care team, using patients who had at least 3 primary care visits in the prior 12 months, but fewer than 10 mental health visits.

†COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

The results of the mid-intervention survey are shown in Table 3. Patients on the intervention team were more likely to report being counseled about smoking, to have been referred to a smoking cessation program, and to have attended a program. In addition, they were more likely to report having received a prescription for bupropion. When we adjusted for baseline differences and for time (as a measure of how much intervention they had been exposed to), the results were essentially unchanged (data not shown).

Table 3.

Mid-intervention Survey, Covering Smoking Cessation Services Received and Health Status

| In last 6 months... | Intervention n = 101 (%) | Control n = 150 (%) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quit for ≥ 1 day | 44 | 41 | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) |

| No smoking in last 30 days | 11 | 7 | 1.5 (0.6–3.7) |

| Provider talked about smoking | 68 | 56 | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) |

| Nicotine patch prescribed | 23 | 14 | 1.8 (0.9–3.5) |

| Bupropion prescribed | 17 | 8 | 2.3 (1.1–5.1) |

| Referred to smoking cessation program | 38 | 23 | 2.1 (1.2–3.6) |

| Attended smoking cessation program | 11 | 4 | 3.6 (1.2–10.5) |

| Referred to Quitline telephone counseling | 9 | 5 | 2.0 (0.7–5.6) |

| Received Quitline telephone counseling | 2 | 2 | 0.99 (0.2–6.0) |

| Current health—Excellent/very good | 27 | 22 | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) |

The post-intervention survey took place 1–6 months after the end of the intervention period. As can be seen in Table 4, all of the difference noted at mid-intervention had disappeared. Patients on both teams were equally likely to report being counseled about smoking, to have been referred to a smoking cessation program, and to have had a smoking cessation medication prescribed. As with the mid-intervention analysis, adjusting for baseline differences and time to follow-up had little effect on the post-intervention results (data not shown).

Table 4.

Post-intervention Survey, Covering Smoking Cessation Services Received and Health Status

| In last 6 months... | Intervention n = 104 (%) | Control n = 147 (%) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quit for ≥ 1 day | 31 | 33 | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) |

| No smoking in last 30 days | 10 | 12 | 0.8 (0.4–1.9) |

| Provider talked about smoking | 56 | 53 | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) |

| Nicotine patch prescribed | 17 | 14 | 1.3 (0.6–2.5) |

| Bupropion prescribed | 11 | 9 | 1.2 (0.5–2.8) |

| Referred to smoking cessation program | 24 | 21 | 1.2 (0.7–2.2) |

| Attended smoking cessation program | 9 | 5 | 1.9 (0.7–5.3) |

| Referred to Quitline telephone counseling | 12 | 7 | 1.8 (0.7–4.3) |

| Received Quitline telephone counseling | 3 | 3 | 1.06 (0.2–4.9) |

| Current health—Excellent/very good | 32 | 21 | 1.7 (1.0–3.1) |

When we compared the results at baseline to the mid-intervention results, the intervention team had no change in the rate of prescribing bupropion or nicotine patches, but the rate of counseling decreased (p = .013). During this same interval, the control team showed no change in the rate of prescribing nicotine patches, but there was a decrease in prescribing bupropion (p = .017) and in counseling about smoking (p = .011). Neither team showed a significant change between baseline and mid-intervention in either the rate of referral to a smoking cessation program or the rate of attending a program. Statistical comparisons between the mid-intervention and post-intervention results were limited by the fact that some subjects responded only to the mid-intervention survey, whereas others responded only to the post-intervention survey.

DISCUSSION

Our study objective was to examine whether the intervention increased rates of smoking cessation treatment, and our results suggest that it did in fact do so. The differences we found between control and intervention teams were observed with a random population-based sample of the entire team. This suggests that our intervention had a significant population-level effect, a conclusion supported by the fact that the differences disappeared at the post-intervention follow-up.

How do our results compare to previous studies? Whereas the effect we found on treatment rates was modest, Hollis et al.31 found that access to an on-site nurse smoking counselor nearly doubled the rate of smoking cessation. In another study, Hollis et al.32 implemented a tobacco counseling model in primary care, and, similar to our results, found a modest increase in treatment rates with the benefit disappearing post-intervention. In terms of educational outreach, our efforts do not appear to have produced any lasting impact on providers’ treatment of smokers; the literature on educational outreach for smoking cessation is similarly inconclusive.23,33,34 A number of studies have shown small to moderate changes in provider behavior, but few addressed smoking cessation. Studies of provider profiling and studies of financial incentives have also shown mixed results.24,25

In the short term, our results are encouraging, as we did find a way to increase smoking cessation treatment rates for a health care population. However, the overall number of referrals made was fairly low. Awareness of the program was high among providers and staff, yet still a few providers generated most of the referrals: only 19% of providers (12/62) generated 52% of referrals, whereas 4 providers alone (6%) generated 32% of referrals. Further research would need to identify ways to increase referrals from infrequent users.

In the long run, the increase in treatment rates seen at mid-intervention disappeared completely by the post-intervention period. This suggests that the educational effect on provider behavior was not sustained and would require a significant, ongoing effort by a health care system to maintain the increased treatment rates.

It is striking to note that whereas the intervention team reported more smoking cessation treatment than the control team, this was not from an increase on the intervention team, but rather from a decrease on the control team. Why should the overall rate of performance decline? The most likely reason is the timeframe: at baseline we asked about services received in the last 12 months, whereas at mid-intervention and post-intervention we asked about the last 6 months. The 2 notable patterns for the data are: (1) that between baseline and mid-intervention, every measure of service—counseling, treatment, referral, and attendance—appeared to decrease on the control team (the difference was statistically significant for counseling and treatment) and (2) between mid- and post-intervention follow-up, there was essentially no difference in care received by the control team.

Our study has several limitations. First, it took place only at 1 site, an academic VA outpatient clinic, which values preventive medicine,13 and it is unclear whether the results would be similar in other settings. A second limitation is that we randomized provider teams, not individual patients. Multilevel modeling could not be used to account for clustering at the team level, as there were only 2 teams. A third limitation is that we did not achieve our target sample size of 330 patients/team. We were still able to show a difference in our primary outcome of differences in smoking cessation treatment rates; however, we might have also found a difference in abstinence rates with a larger sample. A further limitation is a mismatch between the intervention and analysis. Whereas some of our intervention was at the patient level (individual counseling, care management), other parts were at the provider level (access to an on-call counselor, social marketing). Our analysis, however, was primarily at the patient level. Our results should therefore be interpreted with more caution than if we had done a multilevel analysis.

A final limitation is that we had significant loss to follow-up after the baseline survey. However, because our sample was population-based (not related to receipt of the study intervention) and patients were unaware of the intervention, there is no reason for the nonrespondents to have answered differentially between the 2 teams. This makes nonresponse bias very unlikely in our study. Reasons for the poor response rate might include the length of the survey and the fact that Sepulveda’s patients are a frequently surveyed population.

Should a health care system adopt this approach to increase rates of tobacco treatment? Case management approaches have been effectively used by health care organizations for other conditions, and our intervention was effective in increasing referrals and treatment rates. The on-call counselor model’s benefits include ease and convenience for providers and immediate in-depth counseling for patients within the clinic setting with regular follow-up care. We believe this model or a variation of it could successfully be implemented within a facility willing to provide the support necessary to sustain program awareness and use among providers.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (#10RT-0023). This project was done in collaboration with the VA Center of Excellence for the Study of Healthcare Provider Behavior (VA Health Services Research & Development Service # HFP 94-028). An abstract of this study was presented at the 2004 Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine. The authors would like to thank Laura York, MA, for her assistance in editing and preparing this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Coffield AB, Maciosek MV, McGinnis JM, et al. Priorities among recommended clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Jonk YC, Sherman SE, Fu SS, Hamlett-Berry KW, Geraci MC, Joseph AM. National trends in the provision of smoking cessation aids within the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Manag Care 2005;11:77–85. [PubMed]

- 3.Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; June 2000.

- 4.Zhu S, Melcer T, Sun J, Rosbrook B, Pierce JP. Smoking cessation with and without assistance: a population-based analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18:305–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Office of Quality and Performance, Veterans Health Administration. Health Behaviors of Veterans in the VHA: Tobacco Use. 1999 Large Health Survey of Enrollees. October 2001.

- 6.Sherman SE, Yano EM, Lanto AB, Simon BF, Rubenstein LV. Smokers’ interest in quitting and services received: using practice information to plan quality improvement and policy for smoking cessation. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20:33–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Stead LF, Lancaster T. Group behaviour therapy programmes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD001007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Sherman SE, Joseph AM, Yano EM, et al. Assessing the institutional approach to implementing smoking cessation practice guidelines in Veterans Health Administration facilities. Mil Med. 2006;171:80–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Stead LF, Lancaster T, Perera R. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003; 1:CD002850. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Cromwell J, Bartosch WJ, Fiore MC, Hasselblad V, Baker T. Cost-effectiveness of the clinical practice recommendations in the AHCPR guideline for smoking cessation. JAMA 1997; 278:1759–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.McAlister AL, Rabius V, Geiger A, Glynn TJ, Huang P, Todd R. Telephone assistance for smoking cessation: one year cost effectiveness estimations. Tob Control. 2004;13:85–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Rubenstein LV, Yano EM, Fink A, et al. Evaluation of the VA’s Pilot Program in Institutional Reorganization toward Primary and Ambulatory Care: Part I. Changes in process and outcomes of care. Acad Med. 1996 Jul;71:772–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Cope DW, Sherman SE, Robbins A. Restructuring VA ambulatory care and medical education: the PACE model of primary care. Acad Med. 1996;71:761–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Rundle RL. Oft-derided veterans health agency puts data online, saving time, lives. Wall Street J. December 10, 2001:A1.

- 15.Perlin JB, Kolodner RM, Roswell RH. The Veterans Health Administration: quality, value, accountability, and information as transforming strategies for patient-centered care. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 2):828–36. [PubMed]

- 16.Fung CH, Woods JN, Asch SM, Glassman P, Doebbeling BN. Variation in implementation and use of computerized clinical reminders in an integrated healthcare system. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 2):878–85. [PubMed]

- 17.Sherman SE, Wang M, Nguyen R. Predictors of success in a Department of Veterans Affairs smoking cessation program. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:702–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Zhu SH, Anderson CM, Johnson CE, Tedeschi G, Roeseler A. A centralised telephone service for tobacco cessation: the California experience. Tob Control. 2000;9(Suppl 2):1148–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Grimshaw JM, Shirran L, Thomas R, et al. Changing provider behavior: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions. Med Care. 2001;39(Suppl 2):II2–45. [PubMed]

- 20.Lomas J, Enkin M, Anderson GM, Hannah WJ, Vayda E, Singer J. Opinion leaders vs audit and feedback to implement practice guidelines. Delivery after previous cesarean section. JAMA. 1991;265:2202–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Pereles L, Lockyer J, Ryan D, Davis D, Spivak B, Robinson B. The use of the opinion leader in continuing medical education. Med Teach. 2003;25:438–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Freemantle N, Harvey EL, Wolf F, Grimshaw JM, Grilli R, Bero LA. Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;2:CD000172. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:iii–iv, 1–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, O’Brien MA, Oxman AD. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD000259. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Giuffrida A, Gosden T, Forland F, et al. Target payments in primary care: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;3:CD000531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Sherman SE, Lanto AB, Nield M, Yano EM. Smoking cessation care received by veterans with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2003;40(suppl 2):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.California Tobacco Surveys. La Jolla: University of California, San Diego;1999. Available at: http://ssdc.ucsd.edu/tobacco/. Accessed February 15, 2002.

- 28.Jones D, Kazis L, Lee A, et al. Health status assessments using the Veterans SF-12 and SF-36: methods for evaluating outcomes in Veterans Health Administration. J Ambul Care Manage. 2001;24(3):68–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Tarlov A, Ware JE Jr, Greenfield S, Nelson EC, Perring E, Zubkoff M. The medical outcomes study: an application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. JAMA. 1989;262:925–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Lubben JE. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Fam Commun Health. 1988;11:42–52.

- 31.Hollis JF, Lichtenstein E, Vogt TM, Stevens VJ, Biglan A. Nurse-assisted counseling for smokers in primary care. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:521–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Hollis JF, Bills R, Whitlock E, Stevens VJ, Mullooly J, Lichtenstein E. Implementing tobacco interventions in the real world of managed care. Tob Control. 2000;9(Suppl I):i18–i24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Swartz SH, Cowan TM, DePue J, Goldstein MG. Academic profiling of tobacco-related performance measures in primary care. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(Suppl 1):S38–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Albert DA, Anluwalia KP, Ward A, Sadowsky D. The use of ‘academic detailing’ to promote tobacco-use cessation counseling in dental offices. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:1700–6. [DOI] [PubMed]