Abstract

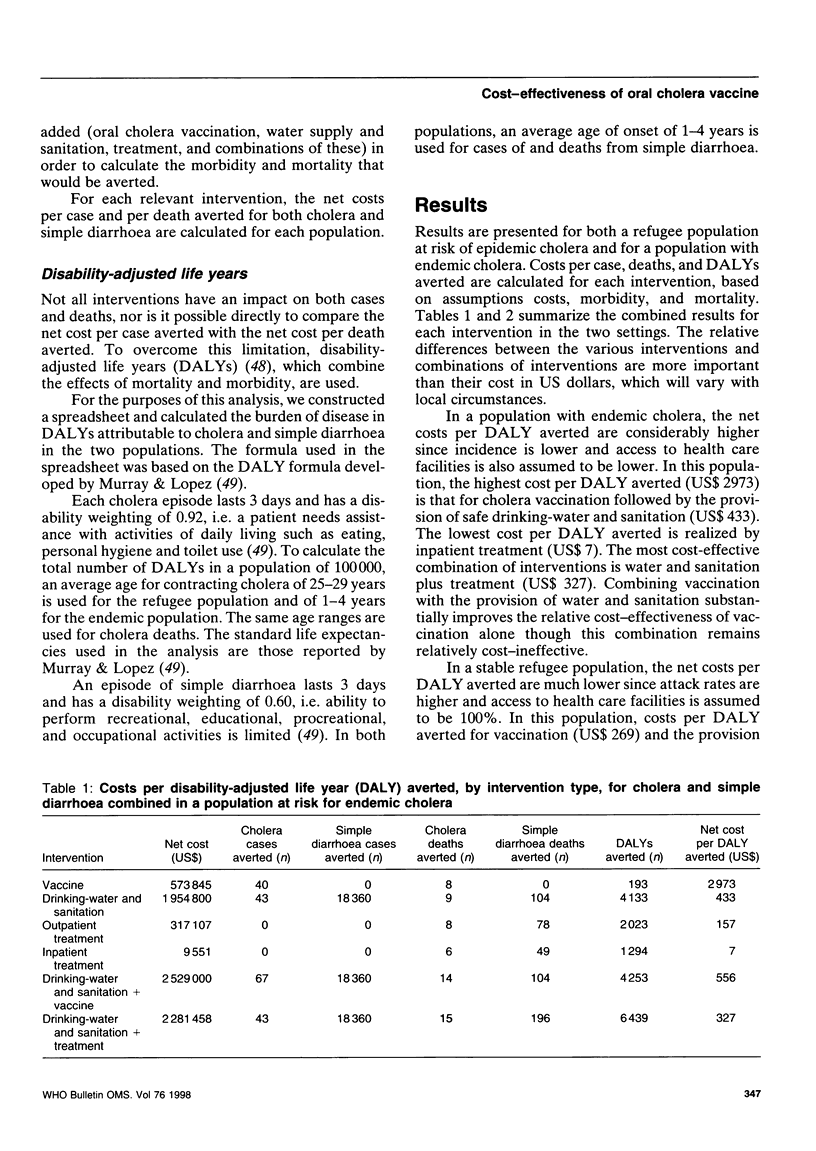

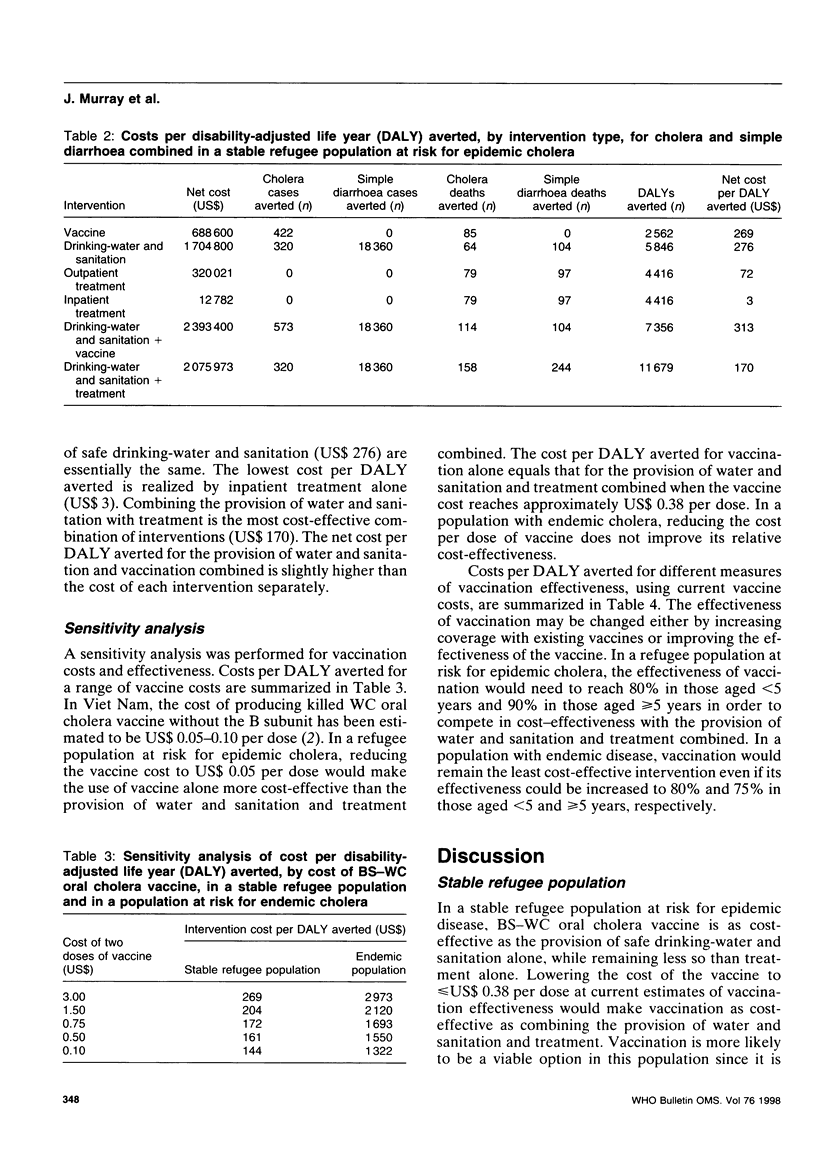

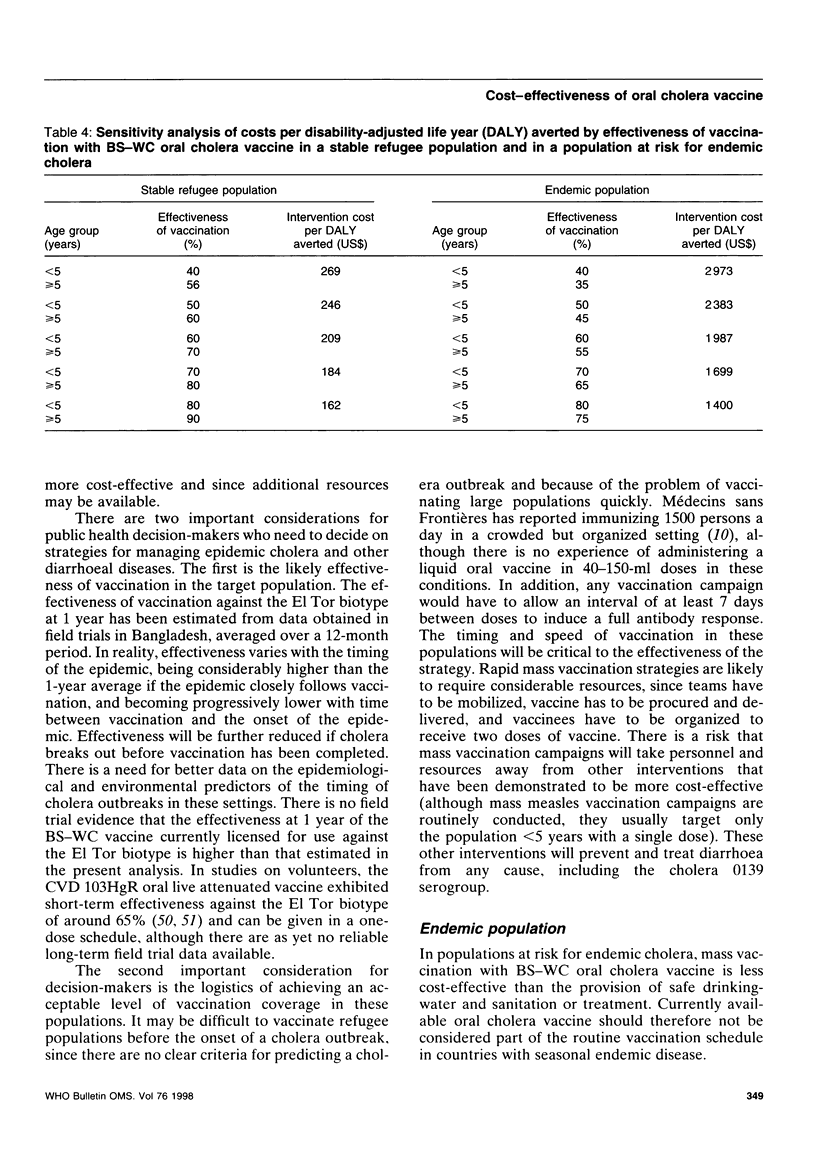

Recent large epidemics of cholera with high incidence and associated mortality among refugees have raised the question of whether oral cholera vaccines should be considered as an additional preventive measure in high-risk populations. The potential impact of oral cholera vaccines on populations prone to seasonal endemic cholera has also been questioned. This article reviews the potential cost-effectiveness of B-subunit, killed whole-cell (BS-WC) oral cholera vaccine in a stable refugee population and in a population with endemic cholera. In the population at risk for endemic cholera, mass vaccination with BS-WC vaccine is the least cost-effective intervention compared with the provision of safe drinking-water and sanitation or with treatment of the disease. In a refugee population at risk for epidemic disease, the cost-effectiveness of vaccination is similar to that of providing safe drinking-water and sanitation alone, though less cost-effective than treatment alone or treatment combined with the provision of water and sanitation. The implications of these data for public health decision-makers and programme managers are discussed. There is a need for better information on the feasibility and costs of administering oral cholera vaccine in refugee populations and populations with endemic cholera.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baqui A. H., Yunus M., Zaman K. Community-operated treatment centres prevented many cholera deaths. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1984 Jun;2(2):92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bern C., Martines J., de Zoysa I., Glass R. I. The magnitude of the global problem of diarrhoeal disease: a ten-year update. Bull World Health Organ. 1992;70(6):705–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black R. E., Merson M. H., Huq I., Alim A. R., Yunus M. Incidence and severity of rotavirus and Escherichia coli diarrhoea in rural Bangladesh. Implications for vaccine development. Lancet. 1981 Jan 17;1(8212):141–143. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90719-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blok L., Sondorp E. Cholera treatment. Lancet. 1994 Oct 8;344(8928):1022–1023. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claeson M., Merson M. H. Global progress in the control of diarrheal diseases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990 May;9(5):345–355. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199005000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens J. D., Harris J. R., Sack D. A., Chakraborty J., Ahmed F., Stanton B. F., Khan M. U., Kay B. A., Huda N., Khan M. R. Field trial of oral cholera vaccines in Bangladesh: results of one year of follow-up. J Infect Dis. 1988 Jul;158(1):60–69. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens J. D., Sack D. A., Harris J. R., Van Loon F., Chakraborty J., Ahmed F., Rao M. R., Khan M. R., Yunus M., Huda N. Field trial of oral cholera vaccines in Bangladesh: results from three-year follow-up. Lancet. 1990 Feb 3;335(8684):270–273. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90080-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esrey S. A., Feachem R. G., Hughes J. M. Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: improving water supplies and excreta disposal facilities. Bull World Health Organ. 1985;63(4):757–772. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esrey S. A., Habicht J. P. Epidemiologic evidence for health benefits from improved water and sanitation in developing countries. Epidemiol Rev. 1986;8:117–128. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esrey S. A., Potash J. B., Roberts L., Shiff C. Effects of improved water supply and sanitation on ascariasis, diarrhoea, dracunculiasis, hookworm infection, schistosomiasis, and trachoma. Bull World Health Organ. 1991;69(5):609–621. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass R. I., Becker S., Huq M. I., Stoll B. J., Khan M. U., Merson M. H., Lee J. V., Black R. E. Endemic cholera in rural Bangladesh, 1966-1980. Am J Epidemiol. 1982 Dec;116(6):959–970. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman S. J., Shepard D. S., Cash R. A. Treatment of diarrhoea in Indonesian children: what it costs and who pays for it. Lancet. 1985 Sep 21;2(8456):651–654. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M. M., Black R. E., Clements M. L., Cisneros L., Nalin D. R., Young C. R. Duration of infection-derived immunity to cholera. J Infect Dis. 1981 Jun;143(6):818–820. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.6.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M. M., Kaper J. B., Herrington D., Ketley J., Losonsky G., Tacket C. O., Tall B., Cryz S. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of recombinant live oral cholera vaccines, CVD 103 and CVD 103-HgR. Lancet. 1988 Aug 27;2(8609):467–470. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalanabis D., Brayton J. B., Mondal A., Pierce N. F. The use of Ringer's lactate in the treatment of children with cholera and acute noncholera diarrhoea. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;46(3):311–319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack W. M., Mosley W. H., Fahimuddin M., Benenson A. S. Endemic cholera in rural East Pakistan. Am J Epidemiol. 1969 Apr;89(4):393–404. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekalanos J. J., Sadoff J. C. Cholera vaccines: fighting an ancient scourge. Science. 1994 Sep 2;265(5177):1387–1389. doi: 10.1126/science.8073279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosley W. H., Bart K. J., Sommer A. An epidemiological assessment of cholera control programs in rural East Pakistan. Int J Epidemiol. 1972 Spring;1(1):5–11. doi: 10.1093/ije/1.1.5-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun D. A. The value of water supply and sanitation in development: an assessment. Am J Public Health. 1988 Nov;78(11):1463–1467. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.11.1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M., Kumate-Rodríguez J., Mota-Hernández F. Costs of treating diarrhoea in a children's hospital in Mexico City. Bull World Health Organ. 1989;67(3):273–280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack D. A. Cholera control. Lancet. 1994 Aug 27;344(8922):616–617. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard D. S. Economic analysis of investment priorities for measles control. J Infect Dis. 1994 Nov;170 (Suppl 1):S56–S62. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.supplement_1.s56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique A. K., Zaman K., Baqui A. H., Akram K., Mutsuddy P., Eusof A., Haider K., Islam S., Sack R. B. Cholera epidemics in Bangladesh: 1985-1991. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1992 Jun;10(2):79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J. D., Merson M. H. The magnitude of the global problem of acute diarrhoeal disease: a review of active surveillance data. Bull World Health Organ. 1982;60(4):605–613. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen R. New cholera vaccines--for whom? Lancet. 1994 Nov 5;344(8932):1241–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90744-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewien K. E., Mós E. N., Yanaguita R. M., Jerez J. A., Durigon E. L., Hársi C. M., Tanaka H., Moraes R. M., Silva L. A., Santos M. A. Viral, bacterial and parasitic pathogens associated with severe diarrhoea in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1993 Sep;11(3):148–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tacket C. O., Losonsky G., Nataro J. P., Cryz S. J., Edelman R., Kaper J. B., Levine M. M. Onset and duration of protective immunity in challenged volunteers after vaccination with live oral cholera vaccine CVD 103-HgR. J Infect Dis. 1992 Oct;166(4):837–841. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.4.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauxe R. V., Holmberg S. D., Dodin A., Wells J. V., Blake P. A. Epidemic cholera in Mali: high mortality and multiple routes of transmission in a famine area. Epidemiol Infect. 1988 Apr;100(2):279–289. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800067418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trach D. D., Clemens J. D., Ke N. T., Thuy H. T., Son N. D., Canh D. G., Hang P. V., Rao M. R. Field trial of a locally produced, killed, oral cholera vaccine in Vietnam. Lancet. 1997 Jan 25;349(9047):231–235. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)06107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zoysa I., Feachem R. G. Interventions for the control of diarrhoeal diseases among young children: rotavirus and cholera immunization. Bull World Health Organ. 1985;63(3):569–583. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]