INTRODUCTION

Increased competition for research funding requires that clinical and health services researchers be focused and efficient if they are to sustain their research programs over their careers. Developing these skills is paramount for trainees and junior faculty. Although career development issues related to overall ‘gestalt’ concerns1, general career building advice2,3, and strategies for obtaining funding4 have been previously addressed, there has been little published about strategies for maximizing one’s focus and efficiency as a clinical or health services researcher5. In this article, we offer a set of such strategies for junior investigators.

First, Know Thyself (The Person)

We begin with a central guiding principle: understanding the goals, needs, and personal characteristics we bring to our careers is critical to making career decisions and selecting strategies to maximize efficiency and focus.

Understanding Your Values and Their Relative Priority We all balance competing demands of work against personal commitments. The relative priority of these demands varies at different times in our lives, and explicitly recognizing their relative importance is essential. Further, it is important to clarify one’s roles and what they require. How do you allocate your work time across research, teaching, and clinical activities? What are your familial responsibilities (both situational and ongoing)? Attaining a workable balance between one’s career and family life is vital to success and satisfaction in each dimension, and reserving time to ‘sharpen the saw’6—to rest, reflect, exercise, restore energy and perspective—is vital to having a full reservoir of energy and drive for continuing one’s work.We recommend you literally write down a “values” statement, indicating what is important to you in each aspect of your life (personal, family, community, career). This can help with explicating your relative priorities and with providing guidance for how to balance time among those different aspects and within each dimension.

Understanding Your Work Style, and Your Strengths and Weaknesses Some people can adhere to internal deadlines by themselves; others need an external deadline or to be accountable to others (e.g., a mentor). Some investigators thrive on multi-tasking; others need to complete tasks serially. Some individuals are natural leaders; others are not. Some prefer large projects with complex multidisciplinary teams; others prefer smaller projects. Understanding what strengths we “bring to the table” helps maximize efficiency as we identify collaborators and resources that complement our strengths. The key is to recognize your values, work style, skills and limitations and then structure work activities based on this self-assessment. Mentors, supervisors, and trusted colleagues can help you identify your strengths and weaknesses and offer strategies to maximize focus and efficiency.

Be Clear on Your Goals Academic medicine includes a range of activities including research, teaching, clinical activities, and mentoring; it is important to understand which dimensions are most and least satisfying. One strategy for clarifying this is to take your “affective temperature” during different activities; identifying those which you enjoy or look forward to the most can help you make decisions about your priorities. Whichever you choose, be constantly mindful of your long-term goals and identify realistic short and intermediate milestones consistent with these goals. Develop a Gantt chart and/or “to do” list to organize goals and tasks and insure that your time commitments are consistent with your priorities. Using such tools to organize a timeline can help you scan the horizon for upcoming commitments, tasks, and deadlines, and help you determine whether to take on additional commitments. Your timeline must be updated regularly, especially if your long-term goals change.You must discipline yourself to meet your deadlines, even informal ones. For example, it is easy to delay submitting a manuscript that is not perfect. However, “perfection is the enemy of the good”, and at the point of diminishing returns, a paper should be submitted. Rewarding the completion of such tasks can give personal satisfaction and help reinforce completion of the next goal. We caution you, however, to not lose the forest for the trees—publications and funding are a means to an end, and a fulfilling career will be determined by work driven by values, and by progress towards vision, not by the number of publications and grants.

Organizing One’s Schedule We recommend creating and following a schedule, including scheduling time to write grants and manuscripts. The schedule should reflect your values, strengths, and weaknesses, and work style, as well as the urgency and importance of each task5. For example, if you write more effectively in the morning, protect this time for writing. From an efficiency standpoint, it may be more beneficial to arise 1 h earlier each day to write for an hour, than to spend three evening hours trying unsuccessfully to concentrate when one is tired from the day.

Second, Know Thy Environment (The Environment)

We all work in environments with formal and informal rules, expectations, and resources. Strategies for learning these rules have been covered in detail2; one must learn the rules and culture of one’s specific environment so as to clearly understand what is valued, the metrics by which success is judged, and resources available to support one’s career (e.g., pilot funds, professional development seminars). Mentors, supervisors, and other experienced investigators are critical to understanding the local environment.

Within your environment, identify mentors and potential collaborators. We advise you to query trainees and other junior faculty regarding strengths and weaknesses of potential mentors and collaborators before establishing working relationships2. It is also important to identify resources to help build your portfolio and career. We urge you to ‘think outside the box’ to actively identify such resources, whether or not they seem available or have been offered to you. Once identified, you should aim to develop skills at negotiating for those resources. Some are better than others at negotiating7, so if necessary, strive to develop such skills8,9.

Funded faculty with available data sets, analysts and statistical resources can often help pave the way for publications and ideas for new funding proposals, which may be more efficient than starting a study from the beginning. It is important to identify potential mentors and co-investigators who have a track record of following through with projects—evidence of a successful publication record, a continued funding stream, and successful former mentees are each signs of a desirable mentors and colleagues.

It is sometimes difficult to find a single mentor to provide both content and methodological expertise. One can often learn from mentors with clinical or health services research skills, even if their focus differs from yours. With creativity, you can organize a mentoring team that capitalizes on local expertise and resources that will support development of your core interests. Your mentoring team can include a senior investigator whose time is more limited, coupled with a more junior investigator. You may seek one or more external mentors with specific technical or content expertise. You also might identify opportunities to participate as a site collaborator in a relevant multi-site study. Here, you could build relationships with mentors, add on small grants, or write papers that amplify the study beyond its main products. Regardless of the specific strategy, choose mentors and colleagues whose personal characteristics complement your own.

Developing successful mentoring relationships is hard work. Mentees must learn when to ask for help and develop focused agendas for meetings to respect mentor time. Effective mentees are also able to disagree with their mentors, while remaining open-minded. If you disagree with your mentor, pose an alternative. We advise against either blindly sticking to your own perspective or applying answers from your mentor that you do not believe in; rather, you should develop skills in discussing your concerns and finding common ground. If you find yourself feeling criticized or overwhelmed by your mentor’s responses, talk to others. This will help you gain perspective and ensure that you are not taking critiques of your work personally. Generally, a much greater cause for alarm is not being adequately critiqued.

You should identify local resources for junior investigators by querying your mentors, senior faculty, and office of research administration. Many medical schools have intramural junior faculty research funding to support pilot work preparatory to a grant proposal, or to provide initial funding for a program of research which can later be leveraged into more substantial funding.

Third, Determine What You Need to Succeed (Person–Environment Fit)

Our recommendations are designed to help you maximize the fit between yourself and your environment. When such “Person–Environment Fit” is not optimal, “strain...develops when there is a discrepancy between the demands of the job and the ability of persons to meet those demands”10, which saps needed energy away from doing your work. Armed with knowledge about yourself and your environment, you and your mentor can identify strategies to enhance your success. Perhaps you spend too much time on administrative tasks, which others can perform-learning to identify persons to whom to delegate, and then to actually delegate such tasks, is an essential survival skill. Perhaps you devote too much time to nonresearch activities, including committee assignments, teaching or clinical activities. Learning to protect one’s time is essential, and this is often a challenge if “opportunities” are presented by someone with direct authority over you. Mentors are essential to helping junior investigators decide what is reasonable.

Manage Volume We recommend careful thought and constant vigilance regarding your work volume. Taking on too many tasks and responsibilities inevitably leads to missed deadlines, personal frustration, and disappointment from mentors, colleagues and superiors. Thus, it is best to manage this volume at the outset, by making careful and thoughtful decisions about what to take on. To make these decisions, one must constantly refer back to one’s mission and goals, and how well each possible activity fits within this framework. If necessary, you may need to offload activities through delegation, or remove activities from your portfolio. In doing this, it is useful to consult your mentor or supervisor, to ensure that you are considering not only your immediate needs but also your career interests and those of your institution.

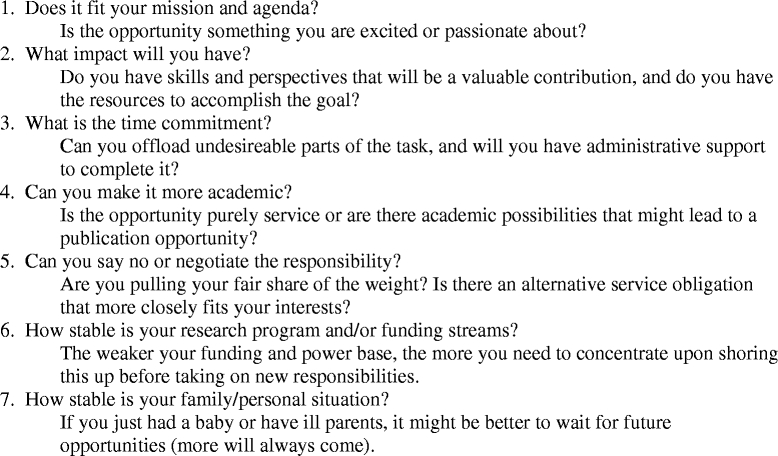

Learn How to Say “No” Knowing when to say “no” and developing skills to do so are crucial to managing work volume. Remember that your time is valuable, and time spent in low priority activities (even when they are “opportunities” from your superiors) detracts from your ability to engage in tasks that are critical for your career. Chin encouraged postponing commitment-making whenever possible, to allow one to think carefully before responding (Figure 1). Thus, following his advice, we urge you to rehearse the response: “Thank you for asking but let me think about it and get back to you” so as to give yourself enough time to discern if a new commitment fits your priorities. In doing so, think about the political realities of the environment—whether doing something will help your center, department, or group—and whether it is important to being a good citizen, or whether it is someone else’s turn to step up for such activities. Engaging one’s mentor/chief to “play the heavy” can be a useful way of saying no, or providing a reason for saying no (e.g. “My mentor advised me against participating in this project”) when it is politically difficult.

Figure 1.

When to Say Yes and when to Say No (reprinted and excerpted with permission from Marshall Chin, MD, MPH, and the Society of General Internal Medicine "Forum" publication)

Minimize Switching Costs ‘Switching costs’ are those associated with excessive multitasking in which switching back and forth between projects incurs significant losses of time and energy associated with refamiliarizing oneself with a prior project, remembering where one left off, and organizing a new set of papers and files11. We encourage minimizing switching costs by focusing primarily on high priority tasks each day or week. The oft-given advice to focus one’s efforts within a certain research content area partly stems from the recognition of the intellectual switching costs involved in mastering multiple content domains (as well as the fact that lack of focus slows one’s progress towards building a national reputation in a specific area). However, sometimes, we must switch tasks: for example, from manuscript to grant proposal preparation; in such cases it becomes important to minimize the switching costs.How one does this depends upon one’s personality. Some work more effectively by designating entire days for certain activities (e.g., Wednesdays are ‘meeting days’, Thursdays are ‘writing days’). Others are comfortable switching tasks after shorter periods. There is no one right answer; you must uncover the strategy that works best for you, and apply it in a way that minimizes wasted time.Various strategies can help minimize switching costs. When stopping work on a project, leave a ‘to do’ list for your return, thereby minimizing the need to rethink where you left off when you reinitiate that project. Always document and date your work, so that if an unexpected interruption to the project occurs, you can more easily reconstruct where you left off and where you need to begin again. Having a written overall project work plan, or “to do” list, helps the sequence of tasks remain clear even if interrupted. Regardless of strategies, maintain an updated “to do” list with deadlines, and review this list with mentors. In addition, consider scanning documents to create electronic, rather than paper, folders, which can be more easily searched using search engines when materials need to be located.

Minimize Interruptions A common interruption is email, which can be ubiquitous and overwhelming. Consider dealing with emails during 1–2 blocks per day. Similar strategies can be adopted from other potential distracters. You might ask to be paged only in emergencies, requesting that nonurgent clinical or other calls be directed to your voice mail. Then, return pages and calls once or twice a day. Try to avoid being called into impromptu meetings. If acceptable in your workplace, consider working somewhere where you will be harder to find, for example, the library. In addition, endeavor to minimize psychic interruptions, that is, distractions to one’s train of thought from oneself. For example, if your priority is writing the science of a grant but you are repeatedly distracted by the many related administrative details, consider keeping a side list of administrative tasks, to which you can attend after your writing time.In summary, career management involves understanding and managing yourself and your environment, as well as the fit between the two. This involves prioritizing and balancing family and work, emphasizing your strengths and supplementing to counter your weaknesses, and knowing your own personal clock. Knowing your work environment will allow you to maximize your productivity by maximizing your use of resources, minimizing switching costs, managing your work volume and learning when and how to say no. No one does this perfectly, but we believe that striving for such balance helps one to be more successful in life.

Acknowledgement

Drs. Kressin, Weaver and Weinberger are supported by Research Career Scientist awards, and Dr. Saha is supported by an Advanced Research Career Development Award from the Health Services Research & Development Service, Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Saha is also supported by a Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar Award from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. We thank Victoria Parker, DBA, for introducing us to the concept of switching costs. This work was previously presented at the 2006 Annual Meeting of the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.Goldman L. Blueprint for a research career in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6:341–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Chin M, et al. Building a research career in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(2):117–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Applegate S, Williams M. Career development in academic medicine. Am J Med. 1990;88:263–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Gill T, et al. Getting funded: Career development awards for aspiring clinical investigators. J Gen Inter Med. 2004;19:472–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Burroughs Wellcome Fund and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Making the Right Moves: a Practical Guide to Scientific Management for Postdocs and New Faculty. 2006, Howard Hughes Medical Institute: Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, and Chevy Chase, Maryland.

- 6.Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. NY, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2004.

- 7.Babcock L, Laschever S. Women Don’t Ask: Negotiation and the Gender Divide. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2003.

- 8.Fisher R, Ury W. Getting to Yes. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin; 1991.

- 9.McCormack M. What They Don’t Teach You at Harvard Business School. New York, NY: Bantam Books; 1984.

- 10.Caplan R, et al. Job Demands and Worker Health. Cincinnati, OH: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health; 1975.

- 11.Rothman J. Multitasking Overhead. 2003.