Abstract

The xeroderma pigmentosum group D (XPD) protein has a dual function, both in nucleotide excision repair of DNA damage and in basal transcription. Mutations in the XPD gene can result in three distinct clinical phenotypes, XP, trichothiodystrophy (TTD), and XP with Cockayne syndrome. To determine if the clinical phenotypes of XP and TTD can be attributed to the sites of the mutations, we have identified the mutations in a large group of TTD and XP-D patients. Most sites of mutations differed between XP and TTD, but there are three sites at which the same mutation is found in XP and TTD patients. Since the corresponding patients were all compound heterozygotes with different mutations in the two alleles, the alleles were tested separately in a yeast complementation assay. The mutations which are found in both XP and TTD patients behaved as null alleles, suggesting that the disease phenotype was determined by the other allele. If we eliminate the null mutations, the remaining mutagenic pattern is consistent with the site of the mutation determining the phenotype.

Keywords: nucleotide excision repair, transcription factor TFIIH, UV irradiation

Three genetic disorders, xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), trichothiodystrophy (TTD), and Cockayne syndrome (CS), are associated with defects in nucleotide excision repair. XP, a highly cancer-prone disorder, has been studied extensively, and the seven complementation groups of excision-defective XPs (XP-A through -G) represent genes whose products partake in the different steps of nucleotide excision repair. These genes have now all been cloned, and nucleotide excision repair has been reconstituted in vitro from purified proteins (1, 2). The XPA protein is required for binding to damaged DNA (3), whereas XPG and XPF (together with its heterodimer partner ERCC1) encode structure-specific nucleases that, respectively, cleave damaged DNA on the 3′ and 5′ sides of the damage (4, 5). This cleavage can occur only after the damaged site has been opened out. This is thought to be achieved by the helicase activities of XPB and XPD. The latter two proteins are subunits of the transcription factor TFIIH complex. TFIIH has two quite separate roles, in nucleotide excision repair and in basal transcription (6). Since TFIIH is absolutely required for all transcription by RNA polymerase II, XPB and XPD are essential genes.

TTD is a disorder quite distinct from XP. Although most patients are sun-sensitive, they are not cancer-prone, and the cardinal features of the disorder, namely sulfur-deficient brittle hair, physical and mental retardation, ichthyosis, and abnormal facies, are not found in XP (7). Despite these differences, sun-sensitive TTD patients have deficiencies in DNA repair very similar to those in XP cells, and cell fusion studies on some 20 TTD families have shown that the defect in all but two of these families can be assigned to the XP-D complementation group (8–10). These findings raise the question as to how mutations in the same gene can be associated with disorders with such different clinical features. There are at least two possibilities. (i) Both disorders may be associated with similar mutations in the XPD gene, but one or other of them may have, in addition, mutations in a second gene (11, 12). Although this idea has not been ruled out, we have been unable to obtain evidence in support of it. (ii) The alternative explanation is that the clinical phenotypes of the patients are determined by the sites of the mutations in the XPD gene. We and others have suggested that XP results from mutations that affect only DNA repair, whereas the features of TTD result from mutations that give rise to subtle abnormalities in transcription (10, 13, 14).

In earlier work in collaboration with the group of C. Weber, we identified mutations in a few TTD and XP cell lines (14–16). However, no clear genotype/phenotype relationships were apparent from these data. Their interpretation was complicated by the finding that all of the individuals reported to date have been compound heterozygotes (i.e., mutations occur at different sites in the two alleles). In such cases the phenotype is, viewed most simply, determined by the residual activity of the less severe of the two alleles. (This assumes that there are no dominant-negative effects of the more severe allele.) The XPD gene is highly conserved in eukaryotes, with 50% amino acid identity between Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad3, Schizosaccharomyces pombe Rad15, and human XPD (17–19). Furthermore, most of the mutations that we have detected in the XPD gene are in highly conserved domains. To address the question of severity of alleles, for several patients we have now constructed the analogous mutations in Sch. pombe rad15 and determined their effects in the haploid state. We have also analyzed the causative mutations in the XPD gene in a large number of XP patients. Our data have enabled us to clarify genotype–phenotype relationships, and they support the hypothesis that the clinical features are dependent on the site of the mutation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture.

All cells were human skin fibroblasts grown in Eagle’s MEM with 15% fetal calf serum. Cell survival and unscheduled DNA synthesis (UDS) were carried out as described previously (20, 21). XP (listed in Table 1) and TTD cell strains were assigned to the XP-D complementation group by using cell fusion followed by measurement of UDS (22, 23).

Table 1.

XP patients and cell strains

| Cell strain | Clinical details (skin) | Neurological abnormalities | Age, yr | UVC cell survival D10,* J⋅m−2* | UDS, %† | Ref(s). |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XPLABE | Sun-sensitive; well protected | − | 15 | 40 | 24 | |

| XP1BR (GM3615) | Sun-sensitive | Severe | 45 | 1.48 | 25–35 | 20 and this paper |

| XP16BR | Sun-sensitive | − | 4 | 0.88 | 25 | This paper |

| XP1DU | Sun-sensitive | 0.88 | 20–35 | 20 and this paper | ||

| XPJCLO | Very sun-sensitive | 0.6 | 30 | This paper | ||

| XP107LO | Sun-sensitive; well protected | − | 5 | 0.72 | 15 | 25 and this paper |

| XP111LO | Sun-sensitive | − | 8 | 11 | 25 | |

| XP135LO | Sun-sensitive; multiple cancers | + | 13 | 1.16 | 25 | This paper |

| XP9MA | Sun-sensitive; several cancers | + | 11 | 15 | 26, 27 | |

| XP1NE (GM436) | Sun-sensitive | + | 44 | 1.16 | 40 | 20 and this paper |

| XP2NE (GM435) | Sun-sensitive | + | 48 | 0.6 | 25–40 | 28 and this paper |

| XP43KO | Sun-sensitive; 1 tumor | − | 31 | 45 | 29 | |

| XP15PV | Sun-sensitive | − | 6 | 25–30 | This paper | |

| XP16PV | Sun-sensitive | − | 12 | 25–30 | This paper | |

| XP22VI | Sun-sensitive; multiple tumors | + | 10 | 25 | This paper | |

| XP23VI | Sun-sensitive; 1 tumor | ± | 20 | 25 | This paper | |

| XP26VI | Very sun-sensitive; multiple tumors | Severe | 15 | 30 | 30, 31 |

UVC dose required to reduce survival to 10%. Because of variations in dosimetry between laboratories and different techniques used, only data on colony-forming ability from the laboratory of S.A.H. and C.F.A. are shown. D10 values for normal cell strains are in the range 10–15 J⋅m−2.

UDS in XP cells expressed as a percentage of that in normal cells.

Mutation Analysis.

Mutations in XPD cDNA were analyzed using procedures described in our earlier work (14, 32). Briefly, RNA extracted from cells was reverse-transcribed into cDNA and then amplified in three or four fragments by using PCR. The fragments were sequenced either directly using cycle sequencing or after insertion into a pGEM5-based T vector.

To screen for mutations at nucleotide numbers 2125/2126 and 1925, a fragment corresponding to nucleotides 1751–2267 was amplified in 50 μl using primers BB17 (TTGAGAACATCCAGAGGAACAAGC) and BB29 (CGGTGGAAGGGCTGTGCCAT). PCR product in 20 μl was digested in 40 μl with 10 units of AciI for 3 h at 37°C, and 15 μl of the digested product was electrophoresed on a 12% polyacrylamide gel for 2 h at 130 V.

Generation of rad15 Mutations.

The rad15 ORF was amplified using PCR with primers containing NdeI and BamHI at the N and C termini, respectively. The PCR product was inserted into the polylinker of pREP81 as a NdeI–BamHI fragment. Sequencing revealed a single error resulting from the PCR, which was corrected using site-directed mutagenesis. Specific mutations were introduced into the rad15 gene by using appropriate mutagenic primers shown in Table 2 in which the mutated base was at the center of the primer. The procedure of Kunkel et al. (33) was used. After the desired mutant clones had been identified, they were all sequenced across the entire rad15 ORF to confirm that no spurious mutations had been introduced. One microgram of mutant rad15 DNA in pREP81 was used to transform rad15::ura4/rad15+ diploid Sch. pombe cells. Diploids containing the rad15 mutant plasmids were sporulated, and haploid cells containing both the ura4 marked deletion and the plasmid-borne mutated rad15 gene were selected by plating the spores on medium selective for ura+ and leu+.

Table 2.

Primers used for mutagenesis of rad15

| Oligonucleotide designation | Oligonucleotide sequence | Resulting amino acid change in Sch. pombe Rad15 | Homologous amino acid change in human XPD |

|---|---|---|---|

| r15M2 | 5′-TAAATTTTTGTGACTGGTTAG-3′ | Arg-111 → His | Arg-112 → His |

| r15M3 | 5′-ACCCCGAGTAACTACTCGTGCAAGTGACAT-3′ | Del 487–492 | Del 488–493 |

| r15M5 | 5′-TGCCATAGTCCATAAAAATTTTTTC-3′ | Arg-721 → Trp | Arg-722 → Trp |

| r15M4 | 5′-TGATTACTGCTGGACCATAATGAT-3′ | Arg-615 → Pro | Arg-616 → Pro |

| ET13 | 5′-CCAAAGCGAGGCGCATATCAGT-3′ | Ser-712 → Arg | Gly-713 → Arg |

| ET12 | 5′-GCAGCATGGCACATGGCATCAAAT-3′ | Arg-657 → Cys | Arg-658 → Cys |

| ET6 | 5′-GACCGACCATACCATTTATCTGCTA-3′ | Arg-682 → Trp | Arg-683 → Trp |

| ET30 | 5′-TCGAGGGGGGATACAGTACCACTCG-3′ | Leu-460 → Val | Leu-461 → Val |

| ET31 | 5′-AATCCCTTCCTGATCAGAAGCGAGGGACATATCAGT-3′ | Del 715–729 | Del 716–730 |

Del, deletion of indicated residues.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mutations in TTD Patients.

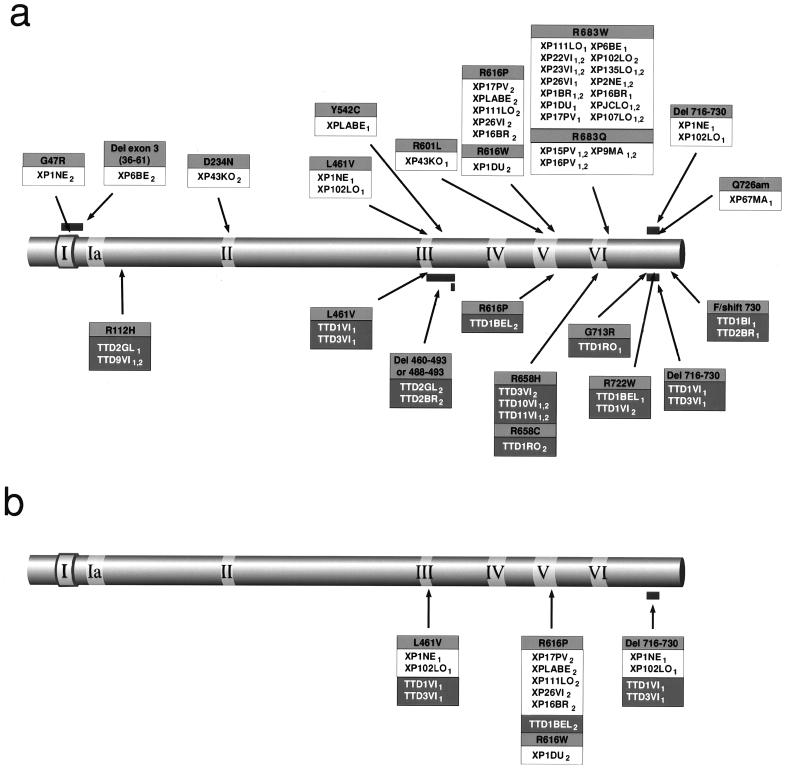

We have previously identified mutations in the XPD gene in various TTD patients (14, 16). These are depicted in the lower part of Fig. 1a. Also shown in this figure are the first homozygous mutations that we have found, in two French families. In strain TTD9VI we have identified an Arg-112 → His mutation, which we had previously detected in the heterozygous state in TTD2GL. The homozygous mutation Arg-658 → His in the siblings TTD10VI and TTD11VI is the same as that previously found in one allele of TTD3VI (16).

Figure 1.

Mutations in the XPD protein. The diagrams show the XPD protein with the seven helicase domains highlighted. Amino acid changes resulting from mutations are shown boxed with the change in black on gray, the cell line designations in black on white (XP) or white on black (TTD). Subscripts 1 and 2 denote the different alleles. (a) All cell lines (mutations found in XP and TTD patients are respectively shown above and below the depicted protein). (b) Mutations found in both XP and TTD.

Mutations in XP Patients.

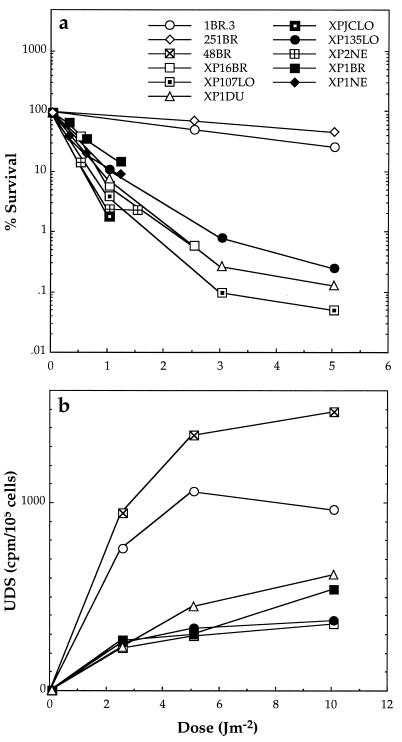

We have determined the sites of the mutations in our collection of XP-D patients. The clinical features and repair defects of the patients are summarized in Table 1, and survival and UDS for several of these strains are presented in Fig. 2. The survivals of the XP-D cell strains following UVC irradiation were very similar, with D10 of approximately 0.6–1.5 J⋅m−2, one-tenth that of normal cells (Fig. 2a). UDS was also similar in all the cell strains, approximately 30% of that in normal cells (Fig. 2b), as previously reported for some of these and other XP-D cell strains.

Figure 2.

Cell survival (a) and DNA repair (UDS) (b) in fibroblast cultures of XP-D cells after UVC irradiation. 1BR.3, 251BR, and 48BR are cultures from normal donors. The rest are from XP-D donors. Results are from single experiments or means of two experiments.

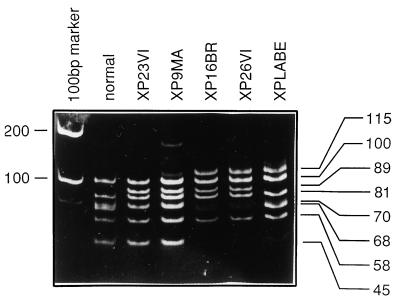

In previous work reported by Takayama et al. (15), three XP patients had the same heterozygous mutation, C2125T, resulting in a change of Arg-683 → Trp. This mutation destroys an AciI site. We have made use of this in a rapid screening procedure to detect this mutation. RNA from XP-D cells was reverse transcribed into cDNA and subsequently amplified by PCR between nucleotides 1751 and 2267. The resulting 517-bp products were digested with AciI, resulting in a series of fragments ranging in size from 21 to 100 bp (Fig. 3, lane 2). Mutation at nucleotide 2125 results in the loss of fragments of 21 and 68 bp with the appearance of a novel 89-bp band. Two examples of this are seen in Fig. 3, lanes 3 and 4. Strains XP23VI and XP9MA are both homozygous for this alteration. We found that the majority of the XP-D cell strains had a heterozygous or homozygous mutation at this locus. To confirm the mutation at 2125, we sequenced across this region in all the patients who were altered at the AciI site. Most of them contained the expected C2125T mutation, but we were surprised to find in two families a different change, namely G2126A, resulting in Arg-683 → Gln rather than Arg-683 → Trp. This was found in the German patient XP9MA (26, 27) and the Italian siblings XP15PV and XP16PV. For the latter the same mutation was found in both parents in the heterozygous state, as expected. Since we have not found mutations at Arg-683 in any TTD donor, our results imply that changes at Arg-683 are likely to be XP-specific mutations.

Figure 3.

AciI digests of PCR products from different cell strains. PCR product from bases 1751–2261 was digested with AciI and electrophoresed on a 12.5% acrylamide gel. The C2125T or G2126A mutation results in loss of 21- and 68-bp fragments and a novel band of 89 bp (lanes 2 and 3 homozygous; lanes 4 and 5 heterozygous). The G1925C (Arg-616 → Pro) mutation causes a loss of bands at 45 and 70 bp with a novel band at 115 bp (heterozygous in lanes 5, 6, and 7).

In addition to the Arg-683 mutations, the same AciI digest revealed the G1925C mutation also found in several cell lines, as discussed further below. Destruction of this AciI site results in 70-and 45-bp bands being replaced by a new fragment of 115 bp. This is seen in Fig. 3, lane 7, for XPLABE, which is heterozygous for this mutation. XP16BR and XP26VI are heterozygous for both mutations, at 1925 and 2125, so that both novel bands at 89 and 115 bp are seen (Fig. 3, lanes 5 and 6). The upper part of Fig. 1a shows the distribution of mutations that we have found in the 17 XP-D patients listed in Table 1 together with four reported previously (15, 34). Of 21 XP-D patients, 17 contained the Arg-683 → Trp or Arg-683 → Gln mutation in one or both alleles. Of the remainder, Japanese patient XP43KO was a compound heterozygote for two mutations not found in other strains; XPLABE had the change Tyr-542 → Cys in one allele, and Arg-616 → Pro in the second allele, the latter having been found in other XPD and TTD strains (see Fig. 1a and below).

XP1NE is the same strain as GM436 examined by Frederick et al. (34). Using single strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP), these authors found a single mutation, Leu-461 → Val, in this strain. This mutation was also found in strains XP102LO, TTD1VI, and TTD3VI (15, 16), but in all of the latter three strains it was associated in the same allele, with a splicing mutation resulting in deletion of 45 bases (2224–2268) in the cDNA and loss of amino acids 716–730 from the protein. We have confirmed the presence of the Leu-461 → Val change in one allele of XP1NE, and as we anticipated we did indeed also detect the 45-bp deletion, confirming that these two mutations are associated in a single haplotype. The mutation in the second allele in this cell strain is G217A, which results in a change of Gly-47 to Arg. This glycine residue is part of the nucleotide-binding sequence GXGKS/T found in many ATP-binding proteins and ATP-dependent DNA helicases. This mutation would be expected to abolish ATPase and DNA helicase activity of the XPD protein.

Use of Sch. pombe rad15 to Study Mutations in Haploid State.

The distribution of mutations in XP-D and TTD cell strains shown in Fig. 1a is disease-specific except for three mutations that we have found in both XP and TTD patients, namely Arg-616 → Pro, Leu-461 → Val, and Del 716–730, the latter two being associated with the same allele (Fig. 1b). At first sight these findings appear to disprove the hypothesis that the site of mutation determines the phenotype. However, patients with these mutations are all compound heterozygotes, and analysis of the individual alleles from these patients, as described below, provides an explanation for this paradox.

To study the effects of the individual alleles, we have taken advantage of the high degree of sequence conservation between the human XPD and the Sch. pombe rad15 gene. We and others previously cloned the rad15 gene and showed that it encodes a 772-aa protein with 55% identity to XPD, and 60–85% identity across the seven helicase domains (18, 19). Like XPD, rad15 is an essential gene, so that deletion mutations can exist only in the same cell as a functional copy of the gene. To separate the effects of the two alleles identified in some of the patients found to be compound heterozygotes, we have generated homologous mutations in rad15 and assessed the ability of these individual alleles to rescue the inviability of a rad15 null mutation. The ORF of the rad15 gene was cloned into the polylinker of the Sch. pombe expression vector pREP81, under control of the nmt1 promoter. Mutations resulting in the same amino acid changes as those found in XP and TTD patients were introduced into the rad15 gene in pREP81 using the procedure of Kunkel et al. (33), and the mutated plasmid was used to transform rad15::ura4+/rad15+ diploid Sch. pombe cells. Diploids containing the plasmid were sporulated, and the spores were plated on medium selective for ura+ and leu+. Only cells containing both the ura4 marked deletion and the plasmid-borne mutated rad15 gene can survive this selection. Viable colonies indicated that the mutated rad15 on the plasmid was able to rescue the lethal phenotype caused by the chromosomal rad15 deletion. On the other hand, a lack of viable colonies showed that the mutated rad15 could not complement the deleted chromosomal allele.

Results are shown in Table 3. In two TTD cell lines, mutations corresponding to one of the alleles were viable, whereas the second alleles were not. Of particular interest is the result with mutations corresponding to those found in TTD1BEL. Arg-616 → Pro is one of these mutations, which we have found in both XP and TTD patients (Fig. 1b). The homologous mutation in rad15 failed to restore viability to the deletion strain, and it can therefore be considered a null allele. In contrast, Arg-722 → Trp, which has been found only in TTD patients (Fig. 1a and unpublished results of E.B. and M.S.), was able to restore viability to the rad15 deletion strain. The other allele found in both XP and TTD patients, namely the combination of Leu-463 → Val and Del 716–730, also failed to restore viability to the rad15 deletion.

Table 3.

TTD and XP mutations in Sch. pombe rad15

| Human cell strain | Repair phenotype | Mutation | Rescue of lethality in Sch. pombe rad15del |

|---|---|---|---|

| TTD2GL | Severe | Arg-112 → His | Yes |

| Del 488–493 | No | ||

| TTD1BEL | Severe | Arg-722 → Trp | Yes |

| Arg-616 → Pro | No | ||

| TTD1RO | Mild | Gly-713 → Arg | Yes |

| Arg-658 → Cys | Yes | ||

| XP-D | Severe | Arg-683 → Trp | Yes |

| Various TTD and XP | Severe | Leu-461 → Val and Del 716–730 | No |

Both mutations corresponding to those identified in strain TTD1RO appear to support viability, and the common XP mutation equivalent to Arg-683 → Trp was also able to rescue viability.

Plasmids containing mutated rad15 genes were also transfected into wild-type Sch. pombe cells. In no case was the viability affected, showing that none of the mutations had a dominant-negative effect on viability.

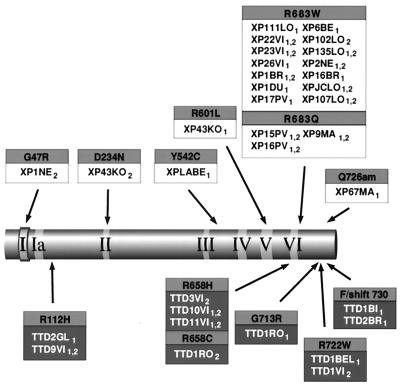

Causative Mutations.

We interpret the data in Table 3 as suggesting that those mutations which do not rescue the proliferative ability of the rad15 deletion are null alleles, and play no part in determining the phenotype in the presence of a less severe allele. (We have also made the assumption that the mutation in XP6BE eliminating the whole of exon 3 is likely to be a null allele.) We have therefore eliminated these putative alleles from Fig. 1a to produce Fig. 4, in which only the functional alleles are depicted. Several conclusions can be drawn from Figs. 1a and 4. (i) Most of the mutations are clustered in the C-terminal third of the protein, with a scattering of mutations close to the N terminus. (ii) There is a region of about 200 aa from residue 234 to residue 460 in which no mutations have been identified. This could have occurred either by chance or because mutations in this region do not generate a recognizable phenotype, or because they have a dominant-negative effect such that the mutated cells would be rendered inviable. We propose to examine these alternatives by using site-directed mutagenesis. (iii) Our data have not delineated discrete domains in the primary structure of the protein in which mutations are associated with the different phenotypes of XP or TTD. This does not, of course, exclude the possibility that the XP mutations on the one hand, and TTD mutations on the other hand, may be found in different physical areas of the protein, when its three-dimensional structure has been determined. (iv) After eliminating putative null alleles, there are no loci at which the same mutation is associated with XP and TTD. Changes at Arg-683 are clearly associated with XP, whereas Arg-112 → His, Arg-722 → Trp, and changes at Arg-658 appear to be associated with TTD. [A TTD patient of Turkish origin was found to be homozygous for the Arg-658 → Cys change, previously found in one allele of TTD1RO, suggesting that this allele is sufficient for the TTD phenotype (unpublished observations of N.G.J.J.).] Interestingly, the six mutational changes of arginine residues at these four sites are all C to T or G to A mutations at CpG sites which are presumed to result from deamination of 5-methylcytosine to thymine.

Figure 4.

Causative mutations in the XPD protein. Designations are as in Fig. 1. Null alleles have been eliminated from Fig. 1a, so that only those mutations thought to be responsible for the phenotype are shown.

Our findings are consistent with our hypothesis that the site of the mutation determines the clinical phenotype.

XPD and TFIIH Functions.

The XPD and XPB proteins are subunits of transcription factor TFIIH. Any mutation which destroys the transcriptional activity of TFIIH will be inviable. This probably accounts for the rarity of XP-B families, only three of which have been identified. XPB is therefore predicted to play a crucial role in TFIIH activity. In contrast, many different mutations have now been identified in the XPD gene, implying that TFIIH transcriptional activity is relatively tolerant toward amino acid changes in the XPD protein. Likewise in the Sac. cerevisiae homologues, many mutations have been isolated in RAD3 (XPD homologue), whereas mutations in RAD25/SSL2 (XPB homologue) have been very difficult to isolate. In RAD3, mutation of Lys-48 to Arg destroys the helicase activity of the protein and confers UV sensitivity, but does not affect viability (35). This implies that the helicase activity of Rad3 is required for nucleotide excision repair but is not involved in transcription. By analogy, it is likely that mutations associated with the XP phenotype destroy the repair function of TFIIH (perhaps by affecting the helicase activity) without affecting its transcriptional activity. In support of this, cell strain XP1NE has one null allele and the second allele contains the change Gly-47 → Arg. Since this glycine residue is an invariant part of the Walker ATP-binding site, it is very probable that this mutant completely lacks ATPase and DNA helicase activity. In contrast to the mutations found in XP cells, we and others have proposed that mutations in TTD patients both destroy repair activity and result in subtle transcriptional abnormalities (10, 13, 14). The TFIIH complex contains at least nine subunits. One can envisage that mutations in the XPD subunit may cause minor structural changes which could modulate its interactions with other subunits, thereby modifying the overall transcriptional activity of the complex.

Sung et al. (36) reported that, when expressed in Sac. cerevisiae, the XPD gene was able to rescue the viability of a rad3 deletion strain, but it could not restore UV resistance to a UV-sensitive rad3 point mutant. The rescued cells grew more slowly than wild-type strains. The same group showed that an XPD gene containing the mutation Arg-722 → Trp that we identified in strain TTD1BEL (Fig. 1a) lost the ability to rescue the viability of the rad3 deletion mutant (37). These authors examined the effects of the human gene in the yeast. We have studied a similar question but with a somewhat different approach. In our experiments we constructed analogous mutations in the homologous fission yeast (Sch. pombe) gene rad15 and determined the effect of the mutated yeast gene on viabilities of the deletion strain. We found, in contrast to the results of Guzder et al. (37), that at least one of the mutations found in each TTD strain did restore viability to rad15 deletions. Our different results are likely to result from the subtle differences in the way our experiments were conducted. Guzder et al. (37) suggest that interaction of wild-type XPD protein with other components of Sac. cerevisiae is already suboptimal, so that introduction of the TTD mutations into the XPD gene further reduces this interaction to below levels necessary to support viability. In our experiments we have, in contrast, used Sch. pombe genes in Sch. pombe cells.

In conclusion, we have made use of the sequence conservation of the XPD gene to unravel the complex genotype–phenotype relationships associated with this gene. Our results support the idea that the clinical phenotype (XP or TTD) can be attributed to the site of the causative mutation. To confirm this hypothesis, mutant mice that carry some of the XP or TTD mutations are currently being generated in collaborating laboratories.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. M. Mezzina and Odile Chevallier-Lagente for complementation studies on XP22VI, XP23VI, and XP26VI, to Dr. K. H. Kraemer for cell strain XPLA-BE, to E. Appeldoorn for carrying out single strand conformation polymorphism analysis on some of the mutants, and to Anna Lehmann and Dr. H. Steingrimsdottir for some of the rad15 mutant constructs. The work was supported in part by a Medical Research Council Genetic Analysis of Human Health supplementation grant to A.R.L. and E.M.T., Commission of the European Communities Human Capital and Mobility Grant CHRXCT940443 to A.R.L. and M.S., and a grant from the Associazone Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro to M.S.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CS

Cockayne syndrome

- Del

deletion

- TTD

trichothiodystrophy

- UDS

unscheduled DNA synthesis

- XP

xeroderma pigmentosum

References

- 1.Aboussekhra A, Biggerstaff M, Shivji M K K, Vilpo J A, Moncollin V, Podust V N, Protic M, Hubscher U, Egly J-M, Wood R D. Cell. 1995;80:859–868. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mu D, Park C H, Matsunaga T, Hsu D S, Reardon J T, Sancar A. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2415–2418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood R D. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:135–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Donovan A, Davies A A, Moggs J G, West S C, Wood R D. Nature (London) 1994;371:432–435. doi: 10.1038/371432a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sijbers A M, de Laat W L, Ariza R R, Biggerstaff M, Wei Y-F, Moggs J G, Carter K C, Shell B K, Evans E, de Jong M C, Rademakers S, de Rooij J, Jaspers N G J, Hoeijmakers J H J, Wood R D. Cell. 1996;86:811–822. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80155-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoeijmakers J H J, Egly J-M, Vermeulen W. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:26–33. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)90006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Itin P H, Pittelkow M R. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;20:705–717. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70096-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stefanini M, Vermeulen W, Weeda G, Giliani S, Nardo T, Mezzina M, Sarasin A, Harper J I, Arlett C F, Hoeijmakers J H J, Lehmann A R. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:817–821. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefanini M, Lagomarsini P, Giliani S, Nardo T, Botta E, Peserico A, Kleijer W J, Lehmann A R, Sarasin A. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:1101–1105. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.6.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vermeulen W, van Vuuren A J, Chipoulet M, Schaeffer L, Appeldoorn E, Weeda G, Jaspers N G J, Priestley A, Arlett C F, Lehmann A R, Stefanini M, Mezzina M, Sarasin A, Bootsma D, Egly J-M, Hoeijmakers J H J. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1994;59:317–329. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lambert W C, Lambert M W. Mutation Res. 1985;145:227–234. doi: 10.1016/0167-8817(85)90031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lehmann A R, Norris P G. Carcinogenesis. 1989;10:1353–1356. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.8.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bootsma D, Hoeijmakers J H J. Nature (London) 1993;363:114–115. doi: 10.1038/363114a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broughton B C, Steingrimsdottir H, Weber C, Lehmann A R. Nat Genet. 1994;7:189–194. doi: 10.1038/ng0694-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takayama K, Salazar E P, Lehmann A R, Stefanini M, Thompson L H, Weber C A. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5656–5663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takayama K, Salazar E P, Broughton B C, Lehmann A R, Sarasin A, Thompson L H, Weber C A. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:263–270. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber C A, Salazar E P, Stewart S A, Thompson L H. EMBO J. 1990;9:1437–1448. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08260.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray J M, Doe C, Schenk P, Carr A M, Lehmann A R, Watts F Z. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:2673–2678. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.11.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds P R, Biggar S, Prakash L, Prakash S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:2327–2334. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.9.2327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehmann A R, Stevens S. Mutation Res. 1980;69:177–190. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(80)90187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arlett C F, Harcourt S A, Cole J, Green M H L, Anstey A V. Mutation Res. 1992;273:127–135. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(92)90074-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vermeulen W, Stefanini M, Giliani S, Hoeijmakers J H J, Bootsma D. Mutation Res. 1991;255:201–208. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(91)90054-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stefanini M, Giliani S, Nardo T, Marinoni S, Nazzaro R, Rizzo R, Trevisan G. Mutation Res. 1992;273:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(92)90073-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraemer K H, Herlyn M, Yspa S H, Clark W H, Townsend G K, Neises G R, Hearing V J. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pawsey S A, Magnus I A, Ramsay C A, Benson P F, Giannelli F. Q J Med. 1979;190:179–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thielmann H W, Popanda O, Edler L, Jung E G. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3456–3470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer E, Thielmann H W, Neundörfer B, Rentsch F J, Edler L, Jung E G. Arch Dermatol Res. 1982;274:229–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00403726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cook K, Friedberg E C, Cleaver J E. Nature (London) 1975;256:235–236. doi: 10.1038/256235a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ichihashi M, Yamamura K, Hiramoto T, Fujiwara Y. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:256–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quilliet X, Chevallier-Lagente O, Eveno E, Stojkovic T, Destee A, Sarasin A, Mezzina M. Mutation Res. 1996;364:161–169. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(96)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stojkovic, T., Defebvre, L., Quilliet, X., Eveno, E., Sarasin, A., Mezzina, M. & Destee, A. (1997) Movement Disorders, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Broughton B C, Thompson A F, Harcourt S A, Vermeulen W, Hoeijmakers J H J, Botta E, Stefanini M, King M, Weber C, Cole J, Arlett C F, Lehmann A R. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:167–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunkel T A, Roberts J D, Zakour R A. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:367–382. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frederick G D, Amirkhan R H, Schultz R A, Friedberg E C. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:1783–1788. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.10.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sung P, Higgins D, Prakash L, Prakash S. EMBO J. 1988;7:3263–3269. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sung P, Bailly V, Weber C, Thompson L H, Prakash L, Prakash S. Nature (London) 1993;365:852–855. doi: 10.1038/365852a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guzder S N, Sung P, Prakash S, Prakash L. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17660–17663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]