Abstract

We have investigated physical distances and directions of transposition of the maize transposable element Ac in Arabidopsis thaliana. We prepared a transferred DNA (T-DNA) construct that carried a non-autonomous derivative of Ac with a site for cleavage by endonuclease I-SceI (designated dAc-I-RS element). Another cleavage site was also introduced into the T-DNA region outside dAc-I-RS. Three transgenic Arabidopsis plants were generated, each of which had a single copy of the T-DNA at a different chromosomal location. These transgenic plants were crossed with the Arabidopsis that carried the gene for Ac transposase and progeny in which dAc-I-RS had been transposed were isolated. After digestion of the genomic DNA of these progeny with endonuclease I-SceI, sizes of segment of DNA were determined by pulse-field gel electrophoresis. We also performed linkage analysis for the transposed elements and sites of mutations near the elements. Our results showed that 50% of all transposition events had occurred within 1,700 kb on the same chromosome, with 35% within 200 kb, and that the elements transposed in both directions on the chromosome with roughly equal probability. The data thus indicate that the Ac–Ds system is most useful for tagging of genes that are present within 200 kb of the chromosomal site of Ac in Arabidopsis. In addition, determination of the precise localization of the transposed dAc-I-RS element should definitely assist in map-based cloning of genes around insertion sites.

The Ac element in maize is a transposable DNA element that moves from one site to another on chromosomes. The molecular features of the Ac element indicate that it encodes a gene for the Ac transposase that is essential for transposition (1, 2). It is flanked by 11-bp terminal inverted repeats and an 8-bp target duplication occurs upon transposition (3–5). Because such structural features are also found in bacterial elements, it is likely that essentially similar mechanisms are involved in transposition of elements in bacteria and plants. With regard to the molecular mechanism of transposition in general, two distinct types of mechanism appear to be involved: “nonreplicative cut-and-paste mechanisms,” wherein the copy number of the element does not increase during transposition; and “replicative transposition mechanisms,” wherein the copy number of the element increases because replicated progeny of the element are transposed to another chromosomal site (6). The Ac element and the bacterial transposable elements Tn10 and Tn7 transpose by cut-and-paste mechanisms (7–10), while the bacteriophage Mu and retrotransposons transpose by replicative mechanisms (11, 12). Transposition by the cut-and-paste mechanism offers advantages for gene-tagging technology, over the replicative type, and the Ac element has been tested for that purpose in maize and in various heterologous plant species (13–21).

For use of the Ac element in gene tagging, an understanding of the pattern of its transposition on a chromosome is clearly important. Previous genetic investigations in various laboratories have shown that Ac is preferentially transposed to a region within the same chromosome (22–31). Insertional mutation of genes near the chromosomal location of Ac have, in fact, been obtained and the tagged genes have been cloned (17, 20, 21, 32). Preferential transposition of Drosophila P elements to nearby chromosomal sites has also been reported (33). However, our knowledge of distances and directions of transposition of Ac and other elements at the molecular level is very limited, and no systematic molecular analysis has been performed. In particular, it has yet to be solved whether Ac can transpose symmetrically or asymmetrically from a donor site on the same chromosome because results of genetic analyses with maize in two laboratories were inconsistent (24, 25).

In the present study, we investigated the molecular patterns of Ac transposition on the chromosomes of Arabidopsis using endonuclease I-SceI (I-SceI). Because I-SceI recognizes a specific 18-bp sequence (34, 35), the expected frequency of occurrence of the cleavage site for this enzyme is less than one for the chromosomes of Arabidopsis and, therefore, if such cleavage sites could be introduced into the Ac element and at the original chromosomal location of the Ac element, the physical distance of transposition could be directly determined by measuring the size of the DNA segment generated by digestion with I-SceI of the genomic DNA. In the present study, in 50% of cases, the transposable element was transposed to various locations on a chromosome within a region of ≈1,700 kb, in both directions, from the original site of the element. Our non-autonomous derivative of Ac with an I-SceI site is useful for cloning genes of interest and for the manipulation of chromosomes, as well as for gene tagging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plants and Bacterial Strains.

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Landsberg erecta was used for isolation of transgenic plants #14, #24, and #246 that carried (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA (see Fig. 1A) and P35SAcTPase#9. Agrobacterium tumefaciens A136 (EHA101) (36) and LBA4404 (pAL4404) (37) were used as the bacterial agents and helper plasmids for transformation of Arabidopsis plants. Transgenic plants were generated by the root-transformation procedure (38, 39). Arabidopsis tester lines NW4, NW6, NW7, NW8, NW9, NW127, and cer5 were supplied by the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (Nottingham, U.K.). The multi-tester line CS3878 and as2 were supplied by the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center at Ohio State University (Columbus).

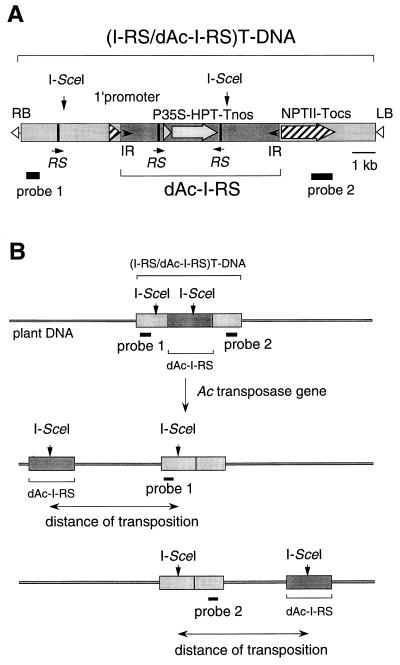

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic diagram of the (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA construct in plasmid pGAHΔNI-RS/dAc-I-RS. dAc-I-RS indicates the non-autonomous derivative of the Ac element that contained I-SceI sites and RSs (see text). (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA indicates the T-DNA that containes a site for I-SceI, RS, and the dAc-I-RS element. LB and RB indicate left and right border sequences on the T-DNA, respectively. I-SceI, the cleavage site for endonuclease I-SceI; 1′ promoter, the 1′ promoter of the octopine Ti plasmid TR-DNA; P35S, the promoter for 35S RNA from cauliflower mosaic virus; HPT, the coding sequence of the gene for hygromycin phosphotransferase; NPTII, the coding sequence of the gene for neomycin phosphotransferase II; Tnos, the terminator of the gene for nopaline synthase; Tocs, the terminator of the gene for octopine synthase; IR, the terminal inverted repeat sequences of Ac; RS, the recombination site that is recognized by the R protein from Zygosaccaromyces rouxii. Thick lines indicate the probes (probes 1 and 2) used for Southern blot analysis. (B) The strategy for measurement of the distance of transposition. I-SceI indicates the site of cleavage by endonuclease I-SceI. A dark grey box indicates dAc-I-RS. Light grey boxes indicate regions of T-DNA other than dAc-I-RS in (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA.

Enzymes, Chemicals, and Plasmids.

Restriction and modifying enzymes were purchased from Takara Syuzo (Kyoto) or Toyobo (Osaka). Hygromycin B and kanamycin sulfate were obtained from Wako Pure Chemical (Osaka). The I-SceI was obtained from Boehringer Mannheim. Cellulase Onozuka RS and Pectolyase Y-23 for the preparation of protoplasts were purchased from Yakult (Tokyo) and Seisin Pharmaceutical (Tokyo), respectively.

Construction of Plasmids.

Details of the procedure for construction of the binary plasmid pGAΔNI-RS/dAc-I-RS, a derivative of pGAHΔN (39) that contained (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA (see Fig. 1A), will be supplied on request. To construct plasmid pGAHΔN35SAcTPase, which contained the cDNA that corresponds to the gene for Ac transposase, the following DNA segments were inserted into the multiple cloning site of pGAHΔN: the 0.8 kb HindIII–XbaI fragment containing the 35S promoter of cauliflower mosaic virus (P35S) from pBI221 (40); synthetic oligonucleotides (5′-CTGATATATATTCTCAAACAAAAAGAATGACGCCTC-3′ and 5′-CGGAGGCGTCATTCTTTTTGTTTGAGAATATATAT-3′) that represented the 5′-upstream region of a parA-related gene (41); a 2.8-kb MspI–EcoRI DNA fragment containing the cDNA for Ac transposase with the polyadenylylation signal of gene 7 of octopine transferred DNA (T-DNA), derived from a derivative of pPCV720 that was supplied by Kunze (1); and a 3-kb HindIII–EcoRI fragment containing the gene for β-glucuronidase with P35S and the nopaline synthase terminator from pBI221. The cDNA for Ac transposase that we used extended from a MspI site (position 997 on the Ac map) to a DraI site (position 4,163 on the Ac map). Details of the procedure for construction of plasmid pGAHΔN35SAcTPase will also be supplied on request.

Induction of Transposition by Crossing Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants and Selection of Plants with a Transposed dAc-I-RS.

The transgenic Arabidopsis lines, #14, #24, and #246, that carried (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA were crossed with the transgenic line P35SAcTPase#9, which carried the gene for Ac transposase, as a pollen parent. F1 plants were self-pollinated and the resulting F2 plants were selected for kanamycin resistance on Murashige and Skoog (MS) basic medium (39) with 35 mg/liter (for lines #14 and #24) or 40 mg/liter (for line #246) kanamycin sulfate. Some F2 plants that grew on MS plates that contained kanamycin but exhibited relatively weak resistance were self-pollinated again and the resulting F3 plants were selected in the same way as described above. F3 plants that were partially kanamycin-resistant were further self-pollinated and the resulting F4 plants were selected as described above.

Preparation of High-Molecular-Weight DNA and Digestion with I-SceI.

High-molecular-weight DNA from Arabidopsis was prepared from protoplasts, which were isolated from segments of seedlings that had been cultured in vitro (42). Protoplasts were prepared by the method described by Ishikawa et al. (43). Protoplasts were finally suspended in 0.6 M mannitol, at a final concentration of ≈2 × 108 protoplasts/ml. High-molecular-weight DNA was prepared from protoplasts as described by Guzmán and Ecker (42) with the following modifications. For preparation of agarose plugs, one volume of a suspension of protoplasts was mixed with one volume of molten 2% low-melting temperature agarose (InCert; FMC). The mixture was poured into plastic molds (2 × 5 × 10 mm3), which were placed on ice for 10 min until the agarose had solidified. The plugs were placed in NDS solution [0.5 M EDTA, pH 8.0/1% sodium N-lauroylsarcosine/2 mg/ml proteinase K (Sigma)] (44), incubated for 48 hr at 50°C and then transferred to fresh NDS for incubation for an additional 48 hr. They were then stored at 4°C. For inactivation of proteinase K, plugs were placed in a solution of 50 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) and incubated for 2 hr at 25°C. Then they were transferred to a solution of 50 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride overnight at 4°C. The plugs were next transferred to a solution of 10 mM Tris⋅HCl and 0.1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) and incubated for 2 hr at 25°C. After transfer to fresh solution they were stored at 4°C. Digestion with I-SceI was performed by the method of Tierry et al. (45) according to the protocol from the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim).

Conditions for Pulse-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE).

PFGE was performed as described (42) in an LKB pulsaphore (Pharmacia LKB). Agarose gels (1% SeaKem LE Agarose; FMC) in 0.5× TBE (0.045 M Tris-borate/1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) were prepared by pouring 120 ml of agarose into a 20 × 20 cm2 frame for separation of DNA fragments of 5–1,000 kb. For separation of DNA fragments of 1–5 mega-base pairs (Mb), agarose gels (0.6% Fast Lane Agarose; FMC) in 0.5× TAE (0.02 M Tris-acetate/0.5 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) were prepared in the 20 × 20 cm2 frame. Plugs containing digested DNA were inserted into gel wells. Electrophoresis was carried out in 0.5× TBE and 0.5× TAE running buffer for separation DNA of 5–1,000 kb DNA and of 1–5 Mb, respectively, and a constant temperature of 10°C was maintained by recirculation of the buffer through a heat exchanger.

Genetic Analysis and Mapping.

To determine the chromosomal linkage of insertion sites of (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA, the transgenic lines (lines #14, #24, and #246) were crossed, as males, with tester lines, and the ratio of mutant phenotypes among progeny of each tester line was determined for the hygromycin-resistant population of F2 progeny. Recombinant fractions were determined by the maximum likelihood procedure (46) and converted to map units (centimorgans) using the Kosambi mapping function (47, 48).

RESULTS

Experimental Design for Measurement of Distances of Transposition with I-SceI.

Fig. 1A shows the T-DNA construct that we made for the determination of distances of transposition. The T-DNA construct had two recognition sites for I-SceI: one was inside and the other was outside the modified Ac transposable element. We designated this element dAc-I-RS because it had the defective Ac element that contained the site for I-SceI and RSs, which are recognition sites for a recombinase (R protein) in the R–RS recombination system from Zygosaccaromyces rouxii (49–53), though details of experimental results with this system will be described elsewhere. We also designated this T-DNA as (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA because the T-DNA construct contained the site for I-SceI, the RS sequence and the dAc-I-RS element. After transposition of dAc-I-RS on the same chromosome, digestion of genomic DNA with I-SceI should give rise a segment of chromosomal DNA flanked by part of the T-DNA at the original integration site and part of the transposed dAc-I-RS sequence (see Fig. 1B). Using two DNA fragments as probes (probes 1 and 2) for Southern blot analysis, as shown in Fig. 1, we were able to distinguish the relative direction of each transposition.

In addition to such specific DNA sequences, we inserted the gene for hygromycin phosphotransferase (HPT) under the control of P35S promoter into the dAc-I-RS element. For monitoring the excision of dAc-I-RS element, this element was inserted into the region between the 1′ promoter (54) and the coding sequence of the gene for neomycin phosphotransferase II (NPTII) to generate a cryptic kanamycin-resistance gene (55). Thus, excision of dAc-I-RS in transgenic Arabidopsis plants that contain (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA should create an active NPTII gene.

Isolation of Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants That Contained the (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA and Induction of Transposition.

We selected transgenic Arabidopsis plants that contained (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA, and we identified plants, designated #14, #24, and #246, that had a single copy of the (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA. The insertion site of (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA in line #14 was mapped to position 80 on chromosome 1 by linkage analysis using tester lines (see Materials and Methods). The (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNAs in lines #24 and #246 were located at the top of chromosome 1 and the bottom of chromosome 2, respectively.

We crossed these transgenic plants with a transgenic plant (designated P35SAcTPase#9) that carried the gene for Ac transposase under the control of the P35S. F1 plants were self-pollinated, and the resulting F2 plants were selected for kanamycin resistance to obtain plants in which the dAc-I-RS element presumably had excised from its original position. Such plants were also obtained from F3 progeny by the similar selection. We carried out Southern blot analysis with genomic DNAs from the F2 and F3 plants to examine the reinsertion of dAc-I-RS. Two-thirds of the F2 and F3 progeny carried transposed dAc-I-RS elements. From line #14 we isolated 103 progeny that exhibited independently transposed dAc-I-RS element. We also isolated 37 and 14 plants with independent reinsertions of dAc-I-RS from transgenic lines #24 and #246, respectively.

Measurement of Physical Distances of Transposition.

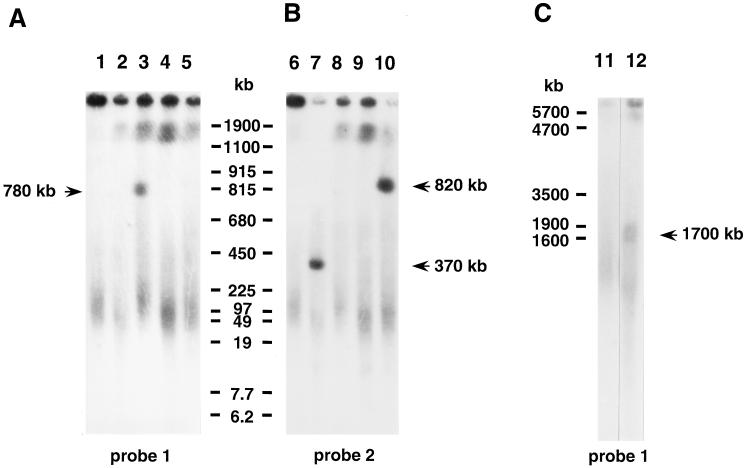

High-molecular-weight chromosomal DNAs were purified from 60, 34, and 9 independent plants with a transposed dAc-I-RS that originated from transgenic lines #14, #24, and #246, respectively. The DNAs were digested with I-SceI. The digests were fractionated by PFGE and subjected to Southern blot analysis with probes 1 and 2 depicted in Fig. 1. When high-molecular-weight chromosomal DNA from line #14 before transposition was digested with I-SceI, we did not detect any discrete fragments of between 5 and 2,000 kb (Fig. 2A, lane 1; Fig. 2B, lane 6; and Fig. 2C, lane 11). When we analyzed plants with the transposed dAc-I-RS, a fragment of 780 kb was detected in the case of the 14-52.2.3 plant (Fig. 2A, lane 3) with probe 1. With probe 2, fragments of 370 and 820 kb were detected in digests of DNA from the 14-20.2.2 and 14-58.3.1 plants, respectively (Fig. 2B, lanes 7 and 10). These results showed that the dAc-I-RS elements in the 14-52.2.3, 14-20.2.2, and 14-58.3.1 plants had been transposed by 780 kb “rightward” [in the direction of the right border (RB) of the T-DNA] and by 370 kb and 820 kb “leftward,” respectively. In the case of plant 14-68.1.4, a 1,700-kb fragment was detected with probe 1 (Fig. 2C, lane 12).

Figure 2.

Southern blot analysis for measurement of the distance of transposition of dAc-I-RS of the pulse-field gel electrophoresis. High-molecular-weight genomic DNA was prepared from Arabidopsis plants that had a transposed dAc-I-RS that originated from line #14, as described. Isolated DNA was digested with I-SceI, and then fractionated by PFGE in a 1% agarose gel for 18 hr at 170 V with a switch interval of 80 sec and then for 3 hr at 170 V with a switch interval of 110 sec (A and B; for analysis of fragments of 5–1,000 kb), and on a 0.6% agarose gel for 3 hr at 50 V with a switch interval of 5 sec and for 7 days at 50 V with a switch interval of 1,800 sec (C; for analysis of fragments of 1–5 Mb). After transfer of the DNA to nitrocellulose membrane filters, filters were probed with probe 1 (A and C) and probe 2 (B), respectively. Smears that were observed around 100 kb (A and B) and 1,000 kb (C) were nonspecific, because they were also found with digests of the line #14 genomic DNA before transposition. Standards are shown with size in kb. Lanes: 1, 6, and 11, the I-RS/dAc-I-RS#14 line (before transposition); 2 and 7, plant 14-20.2.2; 3 and 8, plant 14-52.2.3; 4 and 9, plant 14-52.4.1; 5 and 10, plant 14-58.3.1; and 12, plant 14-68.1.4.

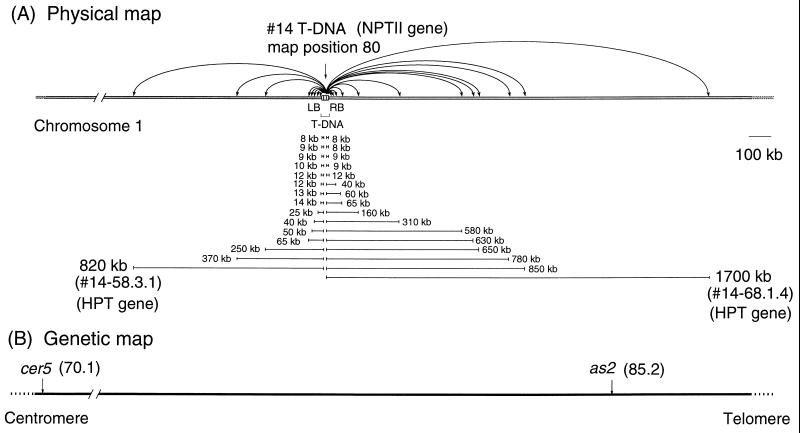

We analyzed a total of 60 transposition events from line #14 in this way. As summarized in Fig. 3 and Table 1, the dAc-I-RS element in 31 plants was transposed within a distance of 1,700 kb. In 21 out of 60 plants, the element was transposed to sites relatively close to the original site (within 200 kb; Table 1, line 1).

Figure 3.

(A) Summary of distances of transposition in the I-RS/dAc-I-RS#14 line. LB and RB indicate left and right border sequences on the T-DNA, respectively. Each bar represents the distance of transposition in each plant that had a transposed dAc-I-RS. Some of the names of F3 progeny plants are indicated in parentheses. (B) Alignment of the genetic map around position 80. Relative positions of the transposed dAc-I-RS elements in plant 14-58.3.1 and plant 14-68.1.4 to as2 and cer5 were determined by three-point test and Southern blot analysis as described in the text.

Table 1.

Summary of distances of transposition of the dAc-I-RS transposable element

| Distance of transposition, kb | Number of plants (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Line #14 (chromosome 1) | Line #24 (chromosome 1) | Line #246 (chromosome 2) | |

| 1–200 | 21 (35.0) | 13 (38.3) | 4 (44.4) |

| 200–600 | 4 (6.7) | 5 (14.7) | 0 (0) |

| 600–1,000 | 5 (8.3) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) |

| 1,000–1,700 | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) |

| Subtotal<1,700 | 31 (51.7) | 19 (55.9) | 5 (55.5) |

| >1,700 or another chromosome | 29 (48.3) | 15 (44.1) | 4 (44.5) |

| Total | 60 (100) | 34 (100) | 9 (100) |

Percentages are relative to the total number of plants analyzed in each transgenic line.

In 29 out of the 60 plants, we detected no fragments of less than 1,700 kb by PFGE under our conditions (Table 1, line 6). We randomly chose 7 plants from this group and analyzed the linkage of the transposed dAc-I-RS element (hygromycin resistance) to the kanamycin-resistance marker at the original site in these plants. In four cases, the transposed element was genetically linked to the original site while in three cases the element had transposed to unlinked sites. These results, together with the results of PFGE, demonstrate that overall, in about 75% of the events studied here, the dAc-I-RS element had transposed to sites that were genetically linked to the original site.

When we analyzed distances of transposition in progeny of transgenic lines #24 and #246, we obtained results similar to those in line #14 (Table 1).

We examined the orientation of the transposed dAc-I-RS elements at the insertion sites by Southern hybridization with probes that contained sequences specific for the left or the right side of the I-SceI site in dAc-I-RS. These results of these experiments showed that the dAc-I-RS element could be inserted in both either orientation (data not shown).

Linkage of Transposed Elements to Known Loci.

To relate “rightward” and “leftward” for T-DNA insert #14 to the genetic map of Arabidopsis, we made three point crosses of the NPTII and HPT and in plant 14-58.3.1 and in plant 14-68.1.4 with flanking genetic loci as2 and cer5 (Tables 2 and 3). We found that the as2 locus was present between the original position of the T-DNA and dAc-I-RS in plant 14-68.1.4, and that dAc-I-RS in plant 14-58.3.1 was located between the original position of the T-DNA and cer5 (Fig. 3). These results also showed that dAc-I-RS elements in plants 14-58.3.1 and 14-68.1.4 were transposed toward the centromere and the telomere at the bottom on the chromosome 1, respectively.

Table 2.

Linkage of transposed elements and the mutant loci cer5 and as2

| Parents | No. of F2 plants examined | No. of F2 plants with the HPT gene and mutant phenotype | No. of F2 plants with the NPTII gene* (%) | No. of F2 plants with no NPTII gene* (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| as2 × 14-58.3.1 (HPT and NPTII genes) | 595 | 19 | 12 (63) | 7 (37) |

| as2 × 14-68.1.4 (HPT and NPTII genes) | 2600 | 13 | 0 (0) | 13 (100) |

| cer5 × 14-58.3.1 (HPT and NPTII genes) | 216 | 13 | 13 (100) | 0 (0) |

Plants exhibiting resistance to hygromycin and a mutant phenotype, cer5 or as2, were examined for the presence of the NPTII gene. Percentages are relative to the total numbers of plants with the HPT gene and mutant phenotype.

Table 3.

Linkage of a transposed element and as2

| Parents | No. of F2 plants examined | No. of F2 plants with the NPTII gene and as2 | No. of F2 plants with the HPT gene* (%) | No. of F2 plants with no HPT gene* (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| as2 × 14-58.3.1 (HPT and NPTII genes) | 299 | 10 | 10 (100) | 0 (0) |

Plants exhibiting resistance to kanamycin and the as2 phenotype were examined for the presence of the HPT gene. Percentages are relative to the total number of plants with the NPTII gene and as2.

Isolation of Morphological Mutants with a Transposed dAc-I-RS.

We searched for mutants with abnormal morphology among 103 plants that had a transposed dAc-I-RS from line #14 and found five mutants. Linkage analysis revealed that two out of the five mutations were closely linked to the transposed dAc-I-RS. One of these two mutations caused various abnormalities in leaf shape and the other caused delayed development and slow growth. These two mutants had dAc-I-RS at a distance of 160 kb and 850 kb from the original site, respectively. Detailed analysis of these mutants will be described elsewhere. The remaining three mutations did not cosegragate with the transposed dAc-I-RS.

DISCUSSION

Patterns of Transposition.

Using a dAc-I-RS element that contained an I-SceI site, we measured the physical distances of transposition of the Ac element from three different loci in Arabidopsis chromosomes. Under our conditions, distances of transposition of up to 1,700 kb were measured. About half of the transposed dAc-I-RS elements were mapped within this region on both sides of the original site of dAc-I-RS. In particular, one-third of transposition target sites were mapped within 200 kb in all three cases. In the present experiment, we used only one transgenic line as a transposase donor. Therefore, our results cannot rule out the possibility that the level of transposase may have some influence on target site distribution. The previous genetic analyses of the range of the transposition of Ac also showed that target sites of transposition were tight clustering around a number of donor loci (26, 27, 30, 31). Patterns of clustering, however, were rather dispersed in some plants (27, 30). Based on these data, Dooner et al. (27), Bancroft and Dean (30) suggested that the pattern of transposition differ from locus to locus.

Although genetic analysis by Greenblatt (24) showed an asymmetry in distribution of target sites adjacent to the donor locus in maize, our result from Arabidopsis clearly showed that elements at different chromosomal locations were transposed almost equally in both directions. Our observation by the molecular analysis is consistent with the genetic result by Dooner and Belachew (25) that there is a roughly equal distribution of transposed Ac elements on either side of the bz donor site in maize. It is likely that sites of transposition targets tend to be clustered almost equally on both sides to donor sites in most chromosomal regions.

The present result can provide a useful information for gene tagging by an Ac–Ds system. The short-range transposition, preferentially within 200 kb, suggests that the Ac element might be useful for disrupting genes that are present in such adjacent regions. If Arabidopsis contains 20,000 genes, the average length of a single gene must be about 5 kb. The probability of direct tagging by the Ac element of a gene that is present between 0 and 200 kb can be estimated to be 99% on an average if we are to screen randomly isolated 1,000 plants that contain transposed elements.

Gene Tagging with I-RS/dAc-I-RS and Unlinked Mutations.

In the present study, we isolated five mutants that gave a Mendelian segregation ratio. However, only two of the mutations were closely linked to the position of the transposed dAc-I-RS. Three out of five mutations were not linked to the transposed element. The occurrence of such unlinked mutations during Ac transposition was previously reported in Arabidopsis (56, 57). One possible explanation for this phenomenon has been proposed: the transposed element might have been retransposed from the first transposed site, in which mutations might have been generated to an unlinked chromosomal site. This possibility is, however, unlikely because our data showed that in 75% of cases the Ac element was transposed to the genetically linked chromosomal site. Moreover, the three unlinked mutants that we obtained had an insertion of dAc-I-RS within 1,700 kb. It therefore may be difficult to explain the unlinked mutations by assuming two sequential transposition events as described above. Bhatt et al. (57) also discussed the possibility that the activity of Tag1, an endogenous transposon of Arabidopsis, might be enhanced in transgenic lines that contain the Ac–Ds element. Our Southern blot analysis of the unlinked mutants in this study showed, however, that the mutations were not tagged by Tag1 (unpublished data). It is possible that the unlinked mutations might have been due to transposition of other unidentified endogenous transposons.

Use of the Transposed dAc-I-RS for Map-Based Cloning of Genes.

Linkage analysis of previously mapped genes, such as as2 and transposed dAc-I-RS elements with hygromycin resistance, together with measurements of physical distances of transposition allowed us to determine the precise positions of these genes and of the dAc-I-RS elements on the chromosomal DNA. In addition, because the transposition site and the original site of the T-DNA include the HPT and NPTII genes, respectively, it should now be easy to obtain recombinants between these resistance genes and the mutant genes. Thus, the dAc-I-RS system should facilitate map-based cloning of genes near the transposition site, as well as gene tagging. Cloning of the AS2 gene is now in progress in our laboratory with plants that have a transposed dAc-I-RS at a site 1,700 kb and 850 kb away from the original site, respectively.

Use of the Transposed dAc-I-RS in Combination with the R–RS Site-Specific Recombination System.

Development of recombinant DNA technology for manipulation of large segments of DNA is of importance for the structural and functional analysis of eukaryotic chromosomes. For development of such a technology in a plant, use of site-specific recombination systems, such as the cre–loxP system, the R–RS system and FLP–FRT systems, has been proposed (39, 58–62). Chromosomal deletions and inversions have been induced in Arabidopsis and tobacco plants by exploitation of these systems (61, 62). However, full exploitation of this system for systematic analysis has been cumbersome, due in part to technical difficulties. One of the aims of our present study was to solve this problem. As shown in Fig. 1, the (I-RS/dAc-I-RS)T-DNA that we constructed contained two RS sequences, namely, recognition sites for a recombinase (R protein) from Z. rouxii. The Arabidopsis plants that we generated in the present study will therefore be useful for a systematic examination of chromosomal deletions mediated by the R–RS system since the physical distance between two RS sequences on the chromosome have been precisely determined.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. B. Baker and J. Shell (Max-Planck-Institüt für Züchtungsforschung, Cologne, Germany) for the gift of the plasmid pKU3 that contained Ac and a cryptic kanamycin-resistance gene, and to Drs. R. Kunze and P. Starlinger (Universität zu Köln, Cologne, Germany) for the gift of the plasmid that contained the cDNA for the Ac transposase. We also thank Prof. F. Osawa (Aichi Institute of Technology and the Research Development Corporation of Japan) for his encouragement and support, and Ms. K. Usami-Hanada for her skilled technical assistance. C.M. was supported by a grant for Precursory Research for Embryonic Science and Technology from the Research Development Corporation of Japan. This work was also supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas and for General Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan (Grant 06278103), and by a grant for Pioneering Research Projects in Biotechnology from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries of Japan.

ABBREVIATIONS

- P35S

cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter

- PFGE

pulse-field gel electrophoresis

- HPT

hygromycin phosphotransferase

- NPTII

neomycin phosphotransferase II

- T-DNA

transferred DNA

- I-SceI

endonuclease I-SceI

References

- 1.Kunze R, Stochaj U, Laufs J, Starlinger P. EMBO J. 1987;6:1555–1563. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coupland G, Baker B, Schell J, Starlinger P. EMBO J. 1988;7:3653–3659. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Döring H P, Tillmann E, Starlinger P. Nature (London) 1984;307:127–130. doi: 10.1038/307127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller-Neumann M, Yoder J I, Starlinger P. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;198:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pohlman R F, Fedoroff N V, Messing J. Cell. 1984;37:635–643. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berg D E, Howe M M, editors. Mobile DNA. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. for Microbiol.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Greenblatt I M, Dellaporta S L. Genetics. 1987;117:109–116. doi: 10.1093/genetics/117.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morisato D, Kleckner N. Cell. 1984;39:181–190. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benjamin H W, Kleckner N. Cell. 1989;59:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bainton R, Gamas P, Craig N L. Cell. 1991;65:805–816. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90388-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craigie R, Mizuuchi K. Cell. 1987;51:493–501. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90645-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujiwara T, Mizuuchi K. Cell. 1988;54:497–504. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walbot V. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1992;43:49–82. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker B, Schell J, Loerz H, Fedoroff N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4844–4848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bancroft I, Jones J D G, Dean C. Plant Cell. 1993;5:631–638. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.6.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long D, Martin M, Swinburne J, Puangsomiee P, Coupland G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10370–10374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.James D W, Jr, Lim E, Keller J, Plooy I, Ralston E, Dooner H K. Plant Cell. 1995;7:309–319. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Springer P S, McCombie W R, Sundaresan V A, Martienssen R A. Science. 1995;268:877–880. doi: 10.1126/science.7754372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chunk G, Robbins T T, Nijjar C, Ralston E, Courtney-Gutterson N, Dooner H. Plant Cell. 1993;5:371–378. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.4.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones D A, Thomas C M, Hammond-Kosack K E, Balint-Kurti P J, Jones J D G. Science. 1994;266:789–793. doi: 10.1126/science.7973631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitham S, Dinesh-Kumar S P, Choi D, Hehl R, Corr C, Baker B. Cell. 1994;78:1–20. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Schaik N, Brink R A. Genetics. 1959;44:725–738. doi: 10.1093/genetics/44.4.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenblatt I M, Brink R A. Genetics. 1962;47:489–501. doi: 10.1093/genetics/47.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenblatt I M. Genetics. 1984;108:471–485. doi: 10.1093/genetics/108.2.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dooner H K, Belachew A. Genetics. 1989;122:447–457. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.2.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones J D G, Carland F, Lim E, Ralston E, Dooner H K. Plant Cell. 1990;2:701–707. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.8.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dooner H K, Keller J, Haper E, Ralston E. Plant Cell. 1991;3:473–482. doi: 10.1105/tpc.3.5.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osborne B I, Corr C A, Prince J P, Hehl R, Tanksley S D, McCormick S, Baker B. Genetics. 1991;129:833–844. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.3.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno M, Chen J, Greenblatt I, Dellaporta S L. Genetics. 1992;131:939–956. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.4.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bancroft I, Dean C. Genetics. 1993;134:1221–1229. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.4.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carrol B J, Klimyuk V I, Thomas C M, Bishop G J, Harrison K, Scofield S R, Jones J D G. Genetics. 1995;139:407–420. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.1.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delong A, Calderon-Urrea A, Dellaporta S L. Cell. 1993;74:757–768. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90522-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tower J, Karpen G K, Craig N, Spradling A C. Genetics. 1993;133:347–359. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.2.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colleaux L, d’Auriol L, Betermier M, Cottarel G, Jacquier A, Galibert F, Dujon B. Cell. 1986;44:521–33. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colleaux L, d’Auriol L, Galibert F, Dujon B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6022–6026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.6022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hood E E, Helmer G L, Fraley R T, Chilton M D. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1291–1301. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1291-1301.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoekema A, Hirsch P R, Hooykaas P J J, Schilperoort R A. Nature (London) 1983;303:179–180. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valvekens D, van montagu M, van Lijsebettens M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:5536–5540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Onouchi H, Nishihama R, Kudo M, Machida Y, Machida C. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;247:653–660. doi: 10.1007/BF00290396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jefferson R A, Kavanagh T A, Bevan M W. EMBO J. 1987;6:3901–3907. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niwa Y, Muranaka T, Baba A, Machida Y. DNA Res. 1994;1:213–221. doi: 10.1093/dnares/1.5.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guzmán P, Ecker J R. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;6:11091–11105. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.23.11091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ishikawa M, Naito S, Ohno T. J Virol. 1993;67:5328–5338. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5328-5338.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwartz D C, Cantor C R. Cell. 1984;37:67–75. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tierry A, Derrin A, Boyer J, Fairhead C, Dujon B, Fey B, Schmitz G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:189–190. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.1.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bailey N T J. The Mathematical Theory of Genetic Linkage. Oxford: Clarendon; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kosambi D D. Ann Eugen. 1944;12:172–175. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koornneef M, van Eden J, Hanhart C J, Stam P, Braaksma F J, Feenstra W J. J Hered. 1983;74:265–272. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Araki H, Jearnpipatkul A, Tatsumi H, Sakurai T, Ushio K, Muta T, Oshima Y. J Mol Biol. 1985;182:191–203. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90338-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsuzaki H, Araki H, Oshima Y. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:955–962. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.2.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Araki H, Nakanishi N, Evans B R, Matsuzaki H, Jayaram M, Oshima Y. J Mol Biol. 1992;225:25–37. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91023-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawasaki H, Matsuzaki H, Nakajima R, Oshima Y. Yeast. 1991;7:859–865. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsuzaki H, Nakajima R, Nishiyama J, Araki H, Oshima Y. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:610–618. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.610-618.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Velten J, Velten L, Hain R, Schell J. EMBO J. 1984;3:2723–2730. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baker B, Coupland G, Fedoroff N, Starlinger P, Schell J. EMBO J. 1987;6:1547–1554. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Altman T, Felix G, Jessop A, Kauschmann A, Uwer U, Pena Cortes H, Wilmitzer L. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;247:646–652. doi: 10.1007/BF00290357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bhatt A M, Page T, Lawson E J R, Lister C, Dean C. Plant J. 1996;9:935–945. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.9060935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Onouchi H, Yokoi K, Machida C, Matsuzaki H, Ohshima Y, Matsuoka M, Nakamura K, Machida Y. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:6373–6378. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.23.6373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Haaren J J, Ow D W. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;23:525–533. doi: 10.1007/BF00019300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Machida C, Onouchi H, Machida Y. Nippon Nougeikagaku Kaishi. 1993;67:711–715. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Medberry S L, Dale E, Qin M, Ow D W. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:485–490. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.3.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Osborne B I, Wirtz U, Baker B. Plant J. 1995;7:687–701. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.7040687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]