Abstract

We have investigated the efficacy of a hairpin ribozyme targeting the 5′ leader sequence of HIV-1 RNA in a transgenic model system. Primary spleen cells derived from transgenic or control mice were infected with HIV-1/MuLV pseudotype virus. A significantly reduced susceptibility to infection in ribozyme-expressing transgenic spleen cells (P = 0.01) was shown. Variation of transgene-expression levels between littermates revealed a dose response between ribozyme expression and viral resistance, with an estimated cut off value below 0.2 copies of hairpin ribozyme per cell. These findings open up possibilities for studies on ribozyme efficacy and anti-HIV-1 gene therapy.

Sequence-specific endoribonucleases, ribozymes, have attracted much interest for their potential in antiviral therapies, against, for instance, HIV-1 infections, as well as in functional genomics studies (1, 2). A large number of hammerhead and hairpin ribozymes engineered to target HIV-1 RNA have been investigated in vitro, with varying, but overall, very encouraging results (reviewed by Sun et al.; ref. 3). Preclinical studies have shown anti-HIV-1 effects ex vivo after successful modification of peripheral blood lymphocytes (4, 5), peripheral blood CD34+ cells (6, 7), or CD34+ cells from cord blood (8, 9). However, no successful clinical studies have been reported yet. With the prospect of an efficient ribozyme-mediated gene therapy, there is a need to address fundamental questions concerning expression and function of ribozymes in vivo, i.e., in a mammalian model system. Initial gene-therapy projects have indeed been criticized (10, 11) for lacking analysis of the underlying biological mechanisms.

Mouse models expressing noncatalytic antisense transgenes have been available since 1990 (12), including those targeting viral mRNA (13, 14). Published mouse in vivo models that use ribozyme include β-2-microglobulin (15), glucokinase (16), transgenic bovine α-lactalbumin (17), transgenic human growth hormone (18), and amelogenin mRNA (19), etc. A transgenic-ribozyme approach also has been applied in rat for autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (20), and delivery of a synthetic ribozyme in rabbit has been shown to target stromelysin mRNA (21). We have generated a series of hammerhead and hairpin ribozyme transgenic mice with the objective of exploring ribozyme expression and function in vivo (ref. 9; this paper; and M.A., unpublished work). In general, mouse models for gene therapy against HIV-1 present a challenge because of the limited host range of HIV-1. To circumvent this problem, we have used HIV-1 pseudotype virus produced from HIV-1-infected human lymphoid cells harboring an amphotropic murine retrovirus (22). The HIV-1 pseudotypes with amphotropic murine leukemia viruses have been shown to infect cells of several species, including mouse (22–26), in which the ubiquitously expressed sodium-phosphate symporter Ram-1 receptor is used for entry (27, 28). For this paper, we have used HIV-1 pseudotype virus to infect mouse primary spleen cells ex vivo with the purpose of studying anti-HIV-1 hairpin ribozyme efficacy in a transgenic mouse model.

Materials and Methods

Cloning.

The CMVhpU5 construct was generated by annealing oligonucleotides coding for the hairpin ribozyme (29) in sense orientation (5′-CGC GTA CAC AAC AAG AAG GCA ACC AGA GAA ACA CAC GTT GTG GTA TAT TAC CTG GTA-3′) and antisense orientation (5′-GAT CTA CCA GGT AAT ATA CCA CAA CGT GTG TTT CTC TGG TTG CCT TCT TGT TGT GTA-3′; Cybergene, Huddinge, Sweden) followed by cloning into our basal ribozyme vector (9) by replacing the 5′ hammerhead ribozyme (MluI/BglII). Authenticity of the construct was verified by DNA sequencing.

Generation of Transgenic Mice.

CMVhpU5 plasmid DNA, linearized with ScaI, was microinjected into the pronucleus of mouse zygotes of the FVB/N strain at the Unit for Embryology and Genetics at Karolinska Institutet. The mice were kept and bred under pathogen-defined barrier conditions. Genomic DNA was isolated from tail biopsies according to standard procedures. Animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the local Animal Research Ethical Committee of Stockholm South.

Production of Pseudotype Virus.

The preparation of the HIV-1 strain IIIB/MuLV pseudotype virus was done as described by Spector et al. (22). In brief, the neomycin-resistant CEM-1B cell line was cultured in RPMI medium 1640 (GIBCO) supplemented with antibiotics and 10% (vol/vol) inactivated FCS at a cell concentration of 5 × 100,000 cells per ml and infected with cell free HIV-1 stock virus (0.5 ml of HIV-1 containing 1–3 ng/ml p24). After 24 h of infection, the CEM-1B cells were washed extensively to remove excess free virus. The cells were resuspended in fresh RPMI medium 1640 containing 400 μg/ml G418 and kept until a 90–100% cytopathic effect was obtained. After centrifugation, cell-free supernatants were characterized by testing for production of HIV-1 p24 antigen as well as for mature infectious HIV-1 particles in murine spleen cells and human peripheral blood lymphocyte and T cell lines. Aliquots (1 ml) were stored at −70°C until used. Two virus stocks were used in this study and were also equilibrated by titration on an Epstein–Barr virus-transformed B-LCL cell line as a reference.

Infection of Mouse Cells.

Mouse splenocytes were prepared for viral challenge by mashing spleens in 10 ml of RPMI medium 1640, followed by centrifugation (360 × g for 10 min) and transfer to 96-well plates (400,000 cells per well). After Con A activation for 24 h, the cells were washed in RPMI medium 1640. At day 0, five replicas of cells for each virus dilution were infected with HIV-1/MuLV for 24 h. Serial virus dilutions were made with physiological saline solution (phosphate-depleted medium). In some experiments, indicated in Results, this incubation step was performed in RPMI medium 1640 instead of physiological saline solution (nondepleted medium). At day 1 after infection, cells were washed twice with 200 μl per well RPMI medium 1640 including 10% (vol/vol) FCS and then cultured in 2 ml per well RPMI medium 1640 with 10% (vol/vol) FCS. Every third day, 50% of the medium was harvested and replaced with new medium. Supernatants were assayed for HIV-1-specific p24 antigen at days 1, 3, and 6 after infection, and tissue culture 50% infective dose (TCID50) was calculated. At each of these time points, cell viability was also determined.

Ribozyme-Expression Analysis.

Total cellular RNA was isolated by using the guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform method (30). The RNase protection assay (RPA) was performed by using the RPA II kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). The [α-32P]UTP- labeled RNA probe, complementary to the CMVhpU5 ribozyme, was transcribed in vitro by using the T3 MAXIscript kit (Ambion) and purified by denaturing PAGE. Protected fragments were separated by denaturing PAGE and imaged by using the FUJIX (Tokyo) Bio-image Analyzer. The density of relevant bands was measured by using the bas 2000 software.

Determination of Ribozyme Copy Number.

A control ribozyme RNA, in part complementary to the probe used for detection of CMVhpU5, was transcribed in vitro, purified by gel filtration, and quantified by spectrophotometry; the integrity of the transcript was confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis. A dilution series of the control RNA was run adjacent to mouse samples in an RPA. After denaturing PAGE, protected fragments were imaged and measured by using the FUJIX Bio-image Analyzer and the bas 2000 software. Mouse ribozyme hybridization signals were compared with hybridization signals by the in vitro transcribed ribozyme over the linear range of the standard curve, and copies per nanogram of RNA were calculated after adjustment of the number of [α-32P]UTP in the respective protected fragments.

Ribozyme RNA in Situ Hybridization.

Cryosections (8 μm) of mouse spleens were thawed and air dried for 30 min, followed by fixation in 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 min. Sections were pretreated with 0.2 M HCl for 10 min; two 5-min washes in 2× SSC (0.15 M sodium chloride/0.015 M sodium citrate, pH 7); digestion by 2.0 μg/ml proteinase K in 0.2 M Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4) for 30 min at 37°C; postfixation in 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 min; and acetylation with 0.25% (vol/vol) acetic anhydride in 0.1 M triethanolamin buffer (pH 8.0) for 10 min. After two washes in 2× SSC for 5 min, the sections were dehydrated and stored in 70% (vol/vol) ethanol at −20°C. Before hybridization, sections were rehydrated in 2× SSC for 5 min. Sections were hybridized to a denatured 33P-labeled riboprobe, complementary to the CMVhpU5 ribozyme, in 40 μl of hybridization solution [50% (vol/vol) formamide/10% (vol/vol) dextran sulfate/2× SSC/1× Denhardt’s solution/0.5 mg/ml tRNA], covered by parafilm, and incubated over night at 56°C. After hybridization, slides were washed: a 5-min and a 20-min wash in 2× SSC/50% (vol/vol) formamide at hybridization temperature, four 10-min washes in 2× SSC at room temperature, a 30-min RNase A treatment at 100 μg/ml in 2× SSC at 37°C, a 10-min wash in 2× SSC/50% (vol/vol) formamide at hybridization temperature, two 5-min washes at room temperature, and finally dehydration through a series of ethanol (70–99.5%) washes and air drying. Slides were dipped in Kodak NTB-2 nuclear track emulsion, exposed for 13 days, and counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin.

Results

Expression from the CMVhpU5 Construct in Transgenic Mice.

The CMVhpU5 construct was cloned by insertion of a hairpin ribozyme core sequence, targeting the 5′ leader sequence of HIV-1, into our previously described basal ribozyme vector (15) under the control of the human CMV IE promoter/enhancer (Fig. 1). Transgenic mice were generated with this construct, and 12 transgenic founder animals (inbred FVB/N background) were identified by Southern blotting; 8 lines were analyzed further, and all were found to express the transgene, although at different levels (data not shown). The antiviral study presented here included transgene heterozygous mice of the G1 generation from two separate transgenic lines, L77 and L99. Expression of CMVhpU5 was ubiquitous in embryos at embryonic days 12.5–14.5, as detected by RNA in situ hybridization, and in all adult organs tested (kidney, liver, lung, and spleen in mice of up to 24 months of age), as detected by RNA in situ hybridization and RPA (data not shown).

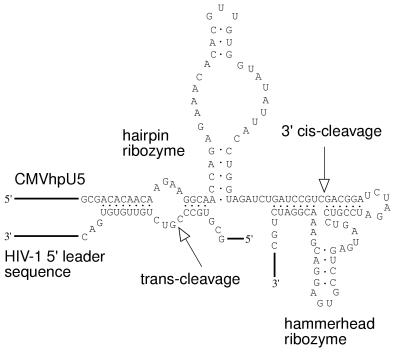

Figure 1.

The CMVhpU5 ribozyme with the trans-targeted HIV-1 U5 sequence aligned (cleavage position +111/112 from the cap site). The primary transcript from the basal ribozyme vector is processed downstream of the trans-cleaving hairpin ribozyme by a cis-cleaving hammerhead ribozyme, producing a transcript with a defined 3′ end. The trans- and cis-cleavage positions are indicated with arrows.

HIV-1/MuLV Pseudotype Infection of Primary Mouse Spleen Cells.

To determine to what extent primary mouse cells can be infected with HIV-1/MuLV pseudotype virus, control and transgenic primary mouse spleen cells were compared ex vivo with a human B cell line and a CD4+ T cell line, because human CD4+ T cells are natural target cells for HIV-1. The highest dilution of pseudotype virus resulting in detection of HIV-1 antigen in the supernatant of infected cells (measured as TCID50) at days 3 and 6 after infection is shown in Table 1. Con A-activated mouse spleen cells were permissive to HIV-1/MuLV pseudotype virus replication, although at a lower degree than the human T cell line (CEM), as has been shown by others (22–26). Up to a 10-fold higher viral dose was required to detect production of p24 antigen in activated FVB/N mouse spleen cells compared with human T cells. The absolute levels of HIV-1 viral antigen produced at respective highest dilution of pseudotype virus were determined by measuring the amount of HIV-1 p24 antigen released into the culture supernatants at days 3 and 6 after infection (Table 1). The release of HIV-1 p24 antigen in supernatants of nontransgenic mouse cells was readily detected and was on average 140-fold lower compared with supernatants of the human T cell line.

Table 1.

Infection of mouse spleen cells and human B and T cell lines by HIV-1/MuLV pseudotype virus

| Highest pseudotype virus amount resulting in detection of HIV-1 p24 antigen (dilution)

|

Amount of HIV-1 p24 antigen in the supernatant of infected cells, pg/0.1 ml

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 6 | Day1 | Day 3 | Day 6 | |

| Control mouse spleen cells | <2 | >10,000 | >10,000 | <6 | 30–250 | 30–250 |

| CMVhpU5 transgenic mouse spleen cells | <2 | 150 | 510 | <6 | 30–125 | 30–125 |

| Human control B cell line, B-LCL | <2 | 600 | 1,000 | <6 | 2,500–5,000 | 10,000–20,000 |

| Human control T cell line, CEM | <2 | 20,000 | 100,000 | <6 | 5,000–10,000 | 10,000–30,000 |

*Cells were analyzed at respective highest dilution of pseudotype virus.

Viral Resistance in CMVhpU5 Transgenic Mouse Spleen Cells.

Spleen cells derived from mice of two transgenic lines (L77 and L99) and age-matched nontransgenic mice were challenged ex vivo with HIV-1/MuLV pseudotype virus in two separate experiments that used the same virus batch (Fig. 2, filled bars). Although some variation was observed among nontransgenic control mice (virus dilution = 700 ± 500), the variation between individual transgenic mice was larger with an average of 190 ± 190, ranging from no resistance (virus dilution > 700) to 22 times lower susceptibility (virus dilution = 32) compared with the nontransgenic control mean value. On average, the CMVhpU5 transgenic spleen cell cultures in experiments I and II required a 3.6 times higher dose for infection and production of HIV-1 viral proteins (P < 0.02), which were measured as the presence of HIV-1 p24 antigen in supernatants. No statistical difference in cell viability was found between control and ribozyme-expressing cells (70–80% at day 3 and 36–57% at day 6).

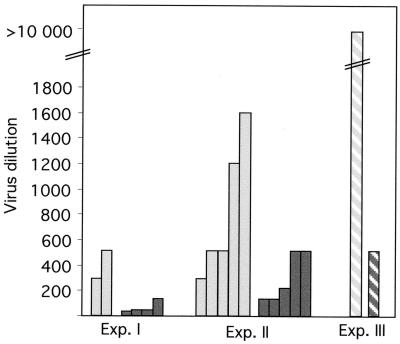

Figure 2.

Infection with HIV-1/MuLV pseudotype virus in individual primary spleen cell cultures (nontransgenic = light grey; CMVhpU5 transgenic = dark grey). Infection and resistance to infection is illustrated by the highest viral dilution still yielding positive p24 antigen values analyzed by ELISA on the supernatants of individual primary spleen cell cultures (five replicas) 6 days after infection. Transgenic mice were heterozygous G1 offspring from two founders. In experiments I and II (filled bars), the mouse spleen cells were cultured in physiological saline solution (phosphate-depleted medium). In experiment III (striped bars), RPMI medium 1640 (phosphate-nondepleted medium) and a 19-fold more concentrated virus were used.

It has been suggested that incubation of cells in phosphate-depleted medium induces an increased cell-surface density of murine leukemia virus receptors and thus facilitates HIV-1/MuLV pseudotype virus infection (28, 31, 32). Phosphate-depleted medium (physiological saline solution) was used during infection in a majority of the experiments in this study. However, in one experiment, we used phosphate nondepleted medium (RPMI medium 1640) during infection (Fig. 2, hatched bars). In this experiment, a more concentrated (approximately 19-fold) virus batch was used to compensate for an expected lack of facilitation of the infection. The results showed a high level of HIV-1 p24 production and a large difference between transgenic and nontransgenic spleen cells.

To determine whether viral resistance in the ribozyme-expressing cells would also correlate with a lower yield of infectious HIV-1 viral particles, supernatants were collected from infected cells cultivated in RPMI medium 1640 at days 3 and 6 after infection. Production of infectious HIV-1 was obtained, as indicated by the ability to infect a human T cell line (Jurkat). Supernatants from nontransgenic control cell cultures were found to contain more than 10,000 TCID50/ml at days 3 and 6 after infection. In accordance with the observed resistance to infection, the yield of infectious particles was considerably lower from CMVhpU5 transgenic spleen cells (64 and 1,000 TCID50/ml cell culture supernatant at days 3 and 6, respectively).

Dose Response in Viral Resistance.

We wanted to examine whether the variation in viral resistance between individual CMVhpU5 transgenic spleen cultures, illustrated in Fig. 2, was paralleled by similar differences in ribozyme-expression levels. The experimental procedure for assaying the HIV-1/MuLV infection did not leave sufficient material to perform a quantitative analysis of ribozyme expression by RPA. To circumvent this problem, we analyzed ribozyme expression in different organs in mice from L99 to see whether other organs could be used as indirect indicators of the expression levels in the spleen. All tested mice from L99 showed consistent ratios for ribozyme-expression levels in the adult kidney, liver, lung, and spleen (data not shown) with levels in kidney closely resembling those in spleen at a ratio of 1:1.1 ± 0.42 (n = 3). Analysis of kidney was therefore chosen for prediction of ribozyme expression in spleens used for pseudotype virus challenge. As could be suspected from the results from the virus-resistance analysis, the ribozyme levels varied between individual transgenic mice, ranging from 0.9 to 27 copies of ribozyme transcripts per nanogram of total cellular kidney RNA in one litter. An estimation of the number of analyzed RNA transcripts per cell was obtained by assuming that a cell contains 30 pg of RNA (33), giving a range of 0.03–0.9 ribozyme copies per cell as a mean for the whole organ. Furthermore, an even distribution of ribozyme expression throughout the transgenic spleen was observed by RNA in situ hybridization (Fig. 3), thereby justifying the use of a mean value for the whole organ as a representation of individual cells.

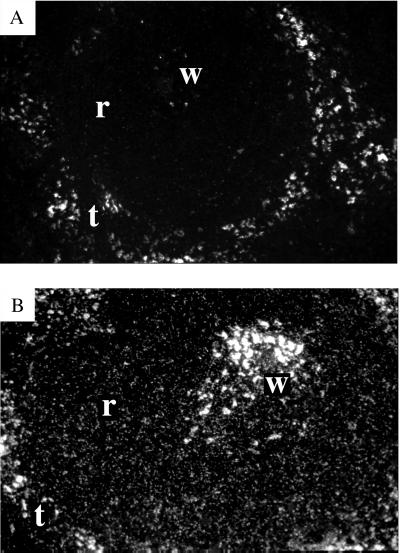

Figure 3.

In situ hybridization of CMVhpU5 ribozyme in mouse spleen. Darkfield images of nontransgenic mouse spleen (A) and CMVhpU5 transgenic mouse spleen (B). Spleen substructures are indicated: white pulp (w), red pulp (r), and trabecula (t). The background seen in white pulp and trabecula is caused by deposition of silver, as verified under lightfield conditions.

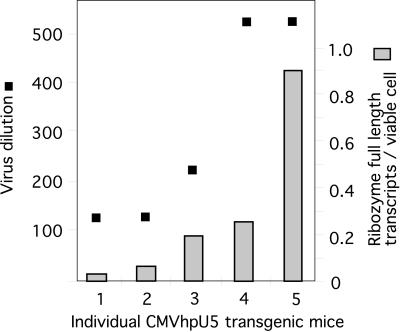

In Fig. 4, expression analysis of kidney RNA is used to plot individual ribozyme-expression levels, whereas spleen cell cultures are used for assaying resistance to HIV-1/MuLV pseudotype virus infection. The results show a clear dose response and possibly also a cutoff value between 0.08 and 0.2 ribozyme copies per cell, below which no antiviral effect is detectable. It should be noted that the values are not linear, because they are based on serial dilutions, which contributes to the nonlinear appearance of the data sets in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Resistance to HIV-1/MuLV pseudotype virus infection in individual mouse spleen cell cultures (illustrated by the highest viral dilution still yielding a measurable HIV-1 p24 antigen production 6 days after infection) plotted against an estimation of ribozyme copy numbers per cell.

In parallel, spleen cell cultures from transgenic mice (n = 4) with a ribozyme construct cloned into the same ribozyme basal vector as CMVhpU5 and targeting a non-HIV-1 related sequence were tested for antiviral effects. When analyzed as above, the expression levels ranged between 12 and 112 copies per cell, and no difference in resistance to HIV-1/MuLV pseudotype virus infection (P > 0.4) was found when compared with nontransgenic spleen cell cultures (n = 3; data not shown).

Discussion

There is a need for a rapid and inexpensive animal model to study and evaluate anti-HIV-1 ribozymes. This study shows the successful use of a transgenic mouse model for this purpose. The expression of a hairpin ribozyme in transgenic spleen cells was correlated to a significantly reduced susceptibility to HIV-1/MuLV pseudotype virus infection. This study also reports HIV-1 pseudotype virus infection of primary mouse cell cultures. We found, consistent with previous findings on cell lines (22–25), that the HIV-1/MuLV pseudotype virus infected mouse spleen cells and produced viable infectious HIV-1 particles but at a significantly lower level than a human T cell line. The mouse cell restriction has been attributed to a reduced capacity of the mouse homolog of human cyclin T1 (CycT1) to support high levels of Tat/TAR trans-activation in mouse cell lines (34–36). However, it seems that different mouse cell types differ in their capacity to be infected by the HIV-1 pseudotype virus and in their potential to express HIV-1 viral proteins in primary cell culture (J.H., unpublished work). It may therefore be inadequate to extrapolate results from undifferentiated cell lines to primary cells.

This study also shows a dose response to ribozyme activity. A surprising and very encouraging result was the estimated very low ribozyme copy number per cell needed for an antiviral effect. This result could be explained in part by the lower efficiency of production of HIV-1 p24 antigen in mouse cells but also gives indirect support for multiple turnover of ribozyme cleavage in vivo (e.g., Sarver et al.; ref. 37). Alternatively, the hairpin ribozyme used may be efficient in targeting the HIV-1 RNA genome before reverse transcription and proviral integration. Previously, a preintegration effect has been inferred from data reported by several groups including our own (38, 39). For the purpose of gene therapy, a possible clinical effect even from very low doses of ribozyme would also shift the focus from achieving very high levels of ribozyme expression to other factors, such as the secondary structure and intracellular localization of the ribozyme (33, 40). This effect highlights the need for more knowledge of the intracellular pathways used by ribozymes and target RNAs and has implications for the development of vector systems for ribozyme-mediated gene therapy against HIV-1 infection.

Other studies that used similar hairpin ribozymes to target the same site in HIV-1 in various expression cassettes have found strong antiviral effects in vitro at considerably higher copy numbers (>103 copies per cell; ref. 7) but also weak or even no effects at still higher levels (>105 copies per cell; ref. 40). However, those studies, all performed in human cell lines, did not investigate low-end cutoff values, which makes a direct comparison with the present study difficult. It remains to be established, by using a wider dose-response range, what the optimal ribozyme copy number is in relation to the anti-HIV-1 effect in our ribozyme transgenic model.

The use of this transgenic model could be enhanced further if the transcriptional and posttranslational restrictions in the mouse could be overcome. Possible future modifications of the model include transgenic expression of human CycT1 to induce efficient Tat/TAR trans-activation in the mouse, as was suggested by Wei et al. (34) and Bieniasz et al. (35).

The presented transgenic model will provide possibilities for functional screening of ribozymes and allow analyses of antiviral effects on different virus isolates, as well as evaluation of proposed strategies for an anti-HIV-1 gene therapy. The restrictions of HIV-1 entrance to mouse cells will ensure that only single infection cycles will take place, thus allowing dissection of preintegration and postintegration effects of the ribozymes studied.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Claudia Devito at Karolinska Institutet for technical help and support with the HIV-1 p24 capture immunoassays and to Rolf Ohlsson, Kristian Svensson, and Helena Malmikumpu at Uppsala University for support and advice on RNA in situ hybridization. We thank Deborah and Stephen Spector at the University of California for providing the CEM-1B cell line. This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Medical Research Council, National Institutes of Health Fogarty, the Swedish Society for Medical Research, the Lars Hierta Foundation, and the Swedish Board for Technical Development.

Abbreviations

- TCID50

tissue culture 50% infective dose

- RPA

RNase protection assay

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Persidis A. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:921–922. doi: 10.1038/nbt0997-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christoffersen R E. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:483–484. doi: 10.1038/nbt0697-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun L Q, Ely J A, Gerlach W, Symonds G. Mol Biotechnol. 1997;7:241–251. doi: 10.1007/BF02740815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leavitt M C, Yu M, Yamada O, Kraus G, Looney D, Poeschla E, Wong-Staal F. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:1115–1120. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.9-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leavitt M C, Yu M, Wong-Staal F, Looney D J. Gene Ther. 1996;3:599–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer G, Valdez P, Kearns K, Bahner I, Wen S F, Zaia J A, Kohn D B. Blood. 1997;89:2259–2267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gervaix A, Li X, Kraus G, Wong-Staal F. J Virol. 1997;71:3048–3053. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3048-3053.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu M, Leavitt M C, Maruyama M, Yamada O, Young D, Ho A D, Wong-Staal F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:699–703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Gervaix A, Kang D, Law P, Spector S A, Ho A D, Wong-Staal F. Gene Ther. 1998;5:233–239. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall E. Science. 1995;270:1751. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verma I M, Somia N. Nature (London) 1997;389:239–242. doi: 10.1038/38410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munir M I, Rossiter B J, Caskey C T. Somatic Cell Mol Genet. 1990;16:383–394. doi: 10.1007/BF01232466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han L, Yun J S, Wagner T E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4313–4317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sasaki N, Hayashi M, Aoyama S, Yamashita T, Miyoshi I, Kasai N, Namioka S. J Vet Med Sci. 1993;55:549–554. doi: 10.1292/jvms.55.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsson S, Hotchkiss G, Andang M, Nyholm T, Inzunza J, Jansson I, Ahrlund-Richter L. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2242–2248. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.12.2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Efrat S, Leiser M, Wu Y J, Fusco-DeMane D, Emran O A, Surana M, Jetton T L, Magnuson M A, Weir G, Fleischer N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2051–2055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huillier P J, Soulier S, Stinnakre M G, Lepourry L, Davis S R, Mercier J C, Vilotte J L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6698–6703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lieber A, Kay M A. J Virol. 1996;70:3153–3158. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3153-3158.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyngstadaas S P, Risnes S, Sproat B S, Thrane P S, Prydz H P. EMBO J. 1995;14:5224–5229. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewin A S, Drenser K A, Hauswirth W W, Nishikawa S, Yasumura D, Flannery J G, LaVail M M. Nat Med. 1998;4:967–971. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flory C M, Pavco P A, Jarvis T C, Lesch M E, Wincott F E, Beigelman L, Hunt S W, III, Schrier D J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:754–758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spector D H, Wade E, Wright D A, Koval V, Clark C, Jaquish D, Spector S A. J Virol. 1990;64:2298–2308. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2298-2308.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasheed S, Gardner M B, Chan E. J Virol. 1976;19:13–18. doi: 10.1128/jvi.19.1.13-18.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chesebro B, Wehrly K, Maury W. J Virol. 1990;64:4553–4557. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4553-4557.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Page K A, Landau N R, Littman D R. J Virol. 1990;64:5270–5276. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5270-5276.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calarota S, Bratt G, Nordlund S, Hinkula J, Leandersson A, Sandstrom E, Wahren B. Lancet. 1998;351:1320–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller D G, Edwards R H, Miller A D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:78–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kavanaugh M P, Miller D G, Zhang W, Law W, Kozak S L, Kabat D, Miller A D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7071–7075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ojwang J O, Hampel A, Looney D J, Wong-Staal F, Rappaport J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10802–10806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chien M L, Foster J L, Douglas J L, Garcia J V. J Virol. 1997;71:4564–4570. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4564-4570.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bunnell B A, Muul L M, Donahue R E, Blaese R M, Morgan R A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7739–7743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bertrand E, Castanotto D, Zhou C, Carbonnelle C, Lee N S, Good P, Chatterjee S, Grange T, Pictet R, Kohn D, et al. RNA. 1997;3:75–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei P, Garber M E, Fang S M, Fischer W H, Jones K A. Cell. 1998;92:451–462. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bieniasz P D, Grdina T A, Bogerd H P, Cullen B R. EMBO J. 1998;17:7056–7065. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.7056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garber M E, Wei P, KewalRamani V N, Mayall T P, Herrmann C H, Rice A P, Littman D R, Jones K A. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3512–3527. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarver N, Cantin E M, Chang P S, Zaia J A, Ladne P A, Stephens D A, Rossi J J. Science. 1990;247:1222–1225. doi: 10.1126/science.2107573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Larsson S, Hotchkiss G, Su J, Kebede T, Andang M, Nyholm T, Johansson B, Sonnerborg A, Vahlne A, Britton S, Ahrlund-Richter L. Virology. 1996;219:161–169. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamada O, Kraus G, Luznik L, Yu M, Wong-Staal F. J Virol. 1996;70:1596–1601. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1596-1601.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Good P D, Krikos A J, Li S X, Bertrand E, Lee N S, Giver L, Ellington A, Zaia J A, Rossi J J, Engelke D R. Gene Ther. 1997;4:45–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]