Abstract

Clinical management of individuals found to harbor a mutation at a known disease-susceptibility gene depends on accurate assessment of mutation-specific disease risk. For missense mutations (MMs)—mutations that lead to a single amino acid change in the protein coded by the gene—this poses a particularly challenging problem. Because it is not possible to predict the structural and functional changes to the protein product for a given amino acid substitution, and because functional assays are often not available, disease association must be inferred from data on individuals with the mutation. Inference is complicated by small sample sizes and by sampling mechanisms that bias toward individuals at high familial risk of disease. We propose a Bayesian hierarchical model to classify the disease association of MMs given pedigree data collected in the high-risk setting. The model’s structure allows simultaneous characterization of multiple MMs. It uses a group of pedigrees identified through probands tested positive for known disease associated mutations and a group of test-negative pedigrees, both obtained from the same clinic, to calibrate classification and control for potential ascertainment bias. We apply this model to study MMs of breast-ovarian susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, using data collected at the Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina.

Keywords: Bayesian analysis, Classification, Family data, Gene characterization, Pedigree analysis, Penetrance

1. INTRODUCTION

An important proportion of human cancer can be attributed to inherited susceptibility (Li 1995; Vogelstein and Kinzler 1998). Naturally occurring mutations of specific genes can generate variants that, when inherited, confer a significantly increased risk of one or more types of cancer (Foulkes and Hodgson 1998). Examples include genes of major public health interest, such as the breast cancer susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 (Miki et al. 1994; Wooster et al. 1995), and colon cancer susceptibility genes in the HNPCC family (Rodriguez-Bigas et al. 1997; Lynch and de la Chapelle 1999). Consistent with common use, we use the terms “variant” and “mutation” interchangeably. Genetic tests for inherited mutations of cancer genes have been developed and are becoming increasingly common (Yan, Kinzler, and Vogelstein 2000). If a sequence variant is found, it can be classified as a deleterious mutation (disease-causing), normal variation (polymorphism or rare variant), or a “variant of unknown significance” (VUS), based on whether it is known to be phenotype-modifying or not. It is established that mutations that lead to premature truncation of the gene product (e.g., frame-shift deletions, insertions, nonsense mutations) are typically considered deleterious. However, for missense mutations (MMs), changes resulting in the substitution of one amino acid for another in the protein sequence, it is difficult to predict whether the change will affect the protein’s function and ultimately modify cancer risk (Cotton and Scriver 1998; see Weiss 1993 for further details and terminology).

MMs as a group are relatively common. For breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, more than 500 distinct MMs have been identified to date (BIC 1997). But, because of these MMs’ large number and the ambiguity of their effects on the protein product, limited progress has been made in understanding their risk effects. As a result, a significant proportion of MMs are VUS. MMs are common among individuals presenting to genetic counseling clinics for testing and advice. Individuals are referred to these clinics on basis of the extent of their family history of disease. In this setting a very serious dilemma arises: Family history indicates a high risk of disease, but the mutation’s significance is unknown. Decisions made on the basis of genetic tests are usually life-changing and often involve radical preventive surgery, such as mastectomy or oophorectomy, exacerbating the dilemma (Grann, Panageas, Whang, Antman, and Neugut 1998).

Two approaches are currently used for characterizing genetic variants. The first of these is to perform a functional assay test of whether the genetic alteration results in modified function. Although highly informative, functional assays are difficult to implement for large numbers of variants. Although particular regions of large genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 have been functionally analyzed, assays for the full genes typically do not exist (Hayes, Cayaran, Barilla, and Monteiro 2000; Vallon-Christersson et al. 2001).

The second approach is to empirically characterize a variant’s disease association using epidemiologic data, for example, a sample of family histories. Mutations of cancer genes do not determine the carrier’s fate, but do confer a substantially increased disease risk. In genetic models, this risk is quantified by a gene’s penetrance functions. These are cumulative probability distributions of developing cancer by age among carriers of a specific genetic variant or collection of variants. We define a variant to be deleterious if its penetrance is increased relative to the penetrance of normal polymorphisms (also called “phenocopy rate”). In family studies, only a few members are typically genotyped, often only the proband. When family data are analyzed, genotypes of the remaining family members are treated as random variables governed by, in the case of known mode of transmission, a specified genetic model for inheritance of the disease genes (see, e.g., Elston and Stewart 1971). For each family member, the likelihood of the observed phenotype is calculated from the relevant penetrance function(s). Hence inference about the disease association of specific genotypes is a statistical question of penetrance estimation. There is a rich literature on estimation of penetrance curves (Elston 1973; Elston and George 1989; Abel and Bonney 1990; Gauderman and Thomas 1994; Li and Thompson 1997). However, analyses specific to individual variants are rare and usually confined to variants with relatively high frequency in a particular subpopulation (Struewing et al. 1997; Oddoux et al. 1996) and, consequently, not to individual missense mutations (Venkitaraman 2001).

One way to progress in this direction is to design studies that obtain more informative epidemiologic data. In this vein, Petersen, Parmigiani, and Thomas (1998) developed a Bayesian approach to evaluate mutation-specific risk and the probability that an MM is deleterious. Their approach is based on a design requiring additional genetic testing of the disease-affected relatives of the first affected individual ascertained in the family (the proband). Although informative and efficient in using limited testing resources, this method is restricted to families with multiple cases and test results. Often, affected relatives are tested only for the mutation found in the proband. If applied retrospectively to existing registries, this selection mechanism may lead to bias. As a prospective approach, it is difficult to implement on a large scale.

With the decreasing cost and growing acceptance of genetic testing, the number of known MMs and other VUSs is rapidly increasing. As a result, consortia such as the National Cancer Institute’s Cooperative Family Registries for Breast and Colorectal Cancer Studies (CFRBCS) and the Cancer Genetics Network (CGN) are accumulating large amounts of relevant family data. These collaborative efforts have made family-based gene/variation characterization a growing interest. Despite this, progress on quantitative methodologies for bringing these kinds of data to bear on questions of genetic susceptibility is still lacking. Concerns that motivate this study include the following:

Most MMs are represented in only a small number of families, making it difficult to estimate a mutation-specific penetrance function.

Although a growing fraction of the data is population-based, much of it is still of high-risk individuals and families, creating a potential for substantial overestimation of penetrance if ascertainment is not carefully dealt with.

Mutations may be missed by testing.

On the brighter side, there is a biological foundation for considering the ensemble of MMs of a gene as likely to be similar in effect, though to an unknown degree.

In exploiting concern 4, one may further account for, for example, whether the mutation encodes a hydrophobic or a hydrophilic base and/or its location in the sequence. The goal of this work is to develop and illustrate a classification methodology that will contribute to a more systematic, accurate, and timely use of available data to characterize inherited susceptibility due to MMs.

The article is organized as follows. In Section 2 we describe the structure of our model in detail. In Section 3 we study the operating characteristics of our hierarchical classification approach in context of a simple simulation experiment where penetrance is assumed to be constant over age and the data are generated under one of three ascertainment rules. In Section 4 we apply the model to study a sample of BRCA1 and BRCA2 MMs obtained from a study of women at high risk of breast cancer conducted at Duke University’s Comprehensive Cancer Center. We provide estimates of the probability that each observed MM is deleterious and estimate the mutation-specific penetrance functions of each. We end the article with a discussion in Section 5.

2. METHOD

Disease-associated gene mutations, including BRCA1 and BRCA2, are rare and expensive to detect. As a result, most available data on tested individuals are generated in clinics or research programs specializing in familial disease, where referrals are made on the basis of features in the family history related to the disease. This is a problem of ascertainment, that is, of sampling based on y when estimating the distribution of y|x (Fisher 1934). Failure to correct for ascertainment may bias penetrance estimates (Elston and Bonney 1984; Ewens and Shute 1986; Sawyer 1990; Dawson 1994; Rabinowitz 1996; Bonney 1998), and is an issue in segregation analysis (Morton 1959; Boehnke and Greenberg 1984; George and Elston 1991; Vieland and Hodge 1995; Elston 1995) and gene characterization (Vinter 1980). One approach to the ascertainment problem is to design studies incorporating population-based sampling schemes (Thomas 1999). Unfortunately, such designs are not practical for the study of specific MMs, because individual variants are too rare.

Because family data are often collected using a variety of complex, sometimes informal, protocols, it can be difficult or impossible to formally condition on ascertainment. Estimates of mutation-specific parameters derived from this type of data without an ascertainment correction will likely be biased, because individuals with high disease rates in their family are more likely to have genetic testing than those in the general population. Likewise, nondeleterious polymorphisms observed in the high-risk setting may also exhibit large numbers of cases among relatives. One approach to this problem is to use a retrospective likelihood (Kraft and Thomas 2000), based on the probability of an observed genotype given a phenotype. If ascertainment depends only on family history, then this corrects for bias, although it may lead to loss of efficiency.

We propose an alternative approach in which we focus on the question of whether individual MMs are deleterious or not. We view this as a classification problem and expand the dataset to incorporate family histories of individuals who tested positive for known deleterious mutations and those who tested negative to form comparison groups against which we classify the observed MMs. Hence the classification procedure is itself implicitly conditional on ascertainment and, importantly, does not require specification of the method of ascertainment or the extremely difficult conditional modeling of family-specific contributions to the likelihood. The only requirement is that all three groups of individuals—mutation negatives, deleterious mutation positives, and MM positives—are ascertained in the same way.

Genotype is measured using biological assays, or “tests,” with imperfect operating characteristics. Failure to correct for assay error is likely to result in biased estimates of mutation effect. In context of the classification, the bias may limit the model’s ability to discriminate between deleterious variants and nondeleterious variants. Assay sensitivity—the probability that an assay finds a mutation when one is present—is less than 1 and varies from method to method and locus to locus, whereas assay specificity—the probability that no mutation is detected when none is present—is nearly 1 across methods for the genes considered here. Indeed, individuals who test positive for a mutation usually receive a confirmatory follow-up test, significantly reducing the possibility of false-positives. Accordingly, we assume that the genotype of individuals who test positive is that indicated by the test. We make no allowance for sensitivity to depend on classification of the variant as may be appropriate for an assay like SSCP.

We build our classification model around Elston and Stewart’s general likelihood for pedigree data (Elston and Stewart 1971). Let Fi denote the family history of disease in family i, typically comprising an indicator of disease, age and age at diagnosis of disease for each member of the family. The probability of Fi is calculated conditional on the population distribution of relevant genotypes, with parameter(s) ν; a genetic model for transmission of the gene(s); and the conditional distribution of the disease phenotype given the genotype, with parameters γ. The latter defines the penetrance curve(s). The likelihood is denoted by Pr(Fi|γ,ν). Let ν index variants. Specifically, let ν = 0 denote the wild-type variant(s), let ν = 1 denote a common unobserved deleterious genotype, and let ν > 1 denote specific observed variants, both known deleterious mutations and MMs. Let d(ν) ∈ {0, 1} indicate the disease causality of variant ν with d(ν) = 1 if variant ν is deleterious and d(ν) = 0 otherwise. By definition, d(0) = 0 and d(1) = 1. Associate with variant ν the scalar penetrance parameter γν ∈ [0, 1]. In principle, the model is easily extended to accommodate vector-valued γν. Let Vi denote the index of the variant(s) carried by the proband of family i.

A critical premise of our model is that deleterious variants of a disease gene will manifest similar disease phenotypes, and, similarly, ascertained nondeleterious variants will reflect common patterns of variation in family history. In keeping with this, we model the γν’s as arising from a two-component mixture model. Component 1, distributed beta(α1, β1), reflects variability in penetrance of nondeleterious variants among ascertained families; component 2, distributed beta(α1,β1), reflects the same for ascertained deleterious variants. MMs are characterized according to their posterior probability of membership in component 2.

Let Ti be the test result for the proband of family i. Let Ti = 0 if no variant or a normal variant is found, and let Ti = ν if a deleterious variant or VUS ν is found. Let Θ = (Γ, π, ξ, α1, β1, α2, β2) be the ensemble of model parameters, where Γ is the vector of γν’s, π is the proportion of ascertained MMs that are nondeleterious, and ξ is the rate of true negatives for the test used. We write the likelihood of observed family histories Fi conditional on Ti and assume that families are independent and that prevalence ν is known. Write

| (1) |

Parameterization of this expression varies according to test result as follows:

The component Pr(Fi|Ti, d(Vi), γVi) is modeled using Elston and Stewart’s (1971) likelihood for pedigree data Fi conditional on the proband carrying a variant of the disease gene with penetrance γVi, an expression evaluated by summing over the genotypes of the untyped family members. Details of this calculation are given in Section 3 and Section 4. For true negatives, we assume that cancer cases in other family members sharing the proband’s disease genotype are due to phenocopying at a rate, captured in the parameter γ0, common to all true negatives in the study.

In fitting this model, we use a Gibbs sampler treating {d(Vi) = 1} as a latent variable in the cases of test-negative families and families that test positive for an MM. For the former, we use the joint prior

and for the latter, we use

where b(·;a, b) denotes the beta density with parameters a and b.

To complete the model, we specify priors and hyperpriors for the model parameters π, ξ, α1, β1, α2, and β2. The choice of prior is based on prior evidence, as well as on computational feasibility. We assume that π, ξ, and (α1, β1, α2, β2) are independent a priori. Assuming that the test specificity is 1, the prior on ξ should be determined by what is known about the sensitivity of the genetic test and prevalence of mutations in the tested population. We choose a relatively vague beta proper prior for π. Finally, we assume that each of α1, β1, α2, and β2 is uniformly distributed on [1, 100] with the constraint that for any γ, the cdf of γ given α1 and β1 must be uniformly greater than that of γ given α2 and β2. This constraint associates, on average, smaller γ’s with nondeleterious variants than with deleterious variants and ensures identifiability of parameters associated with mixture components.

Inference is focused on the posterior probability that d(V) = 1 for each observed missense variant V. Classification of a variant may be achieved by thresholding this probability, for example, in the context of a decision analysis. The model we describe requires that all family histories used in the analysis are collected using the same ascertainment procedure and that ascertainment and assay result are independent conditional on family history. Operationally, this suggests that they are all recruited into the same high-risk study or by the same high-risk clinic. The power of this approach is that it is not necessary to explicitly correct for ascertainment, because this has been achieved implicitly.

We in effect use the likelihood Pr(Fi|γ) to distill from Fi a low-dimensional, model-based summary of a variant’s disease association, comparable from variant to variant and across pedigrees. We then classify the MMs with respect to this summary. An alternative would be to build an empirical classification model using a set of variables that summarize the extent of disease in the pedigree, trained on known deleterious and highly likely-negative families, and use the resulting model to classify MMs with the same ascertainment. Disadvantages of this approach include that it is ad hoc and may ignore known genetic structure in the data, likely resulting in diminished power for discrimination, and that difficulties may be encountered in defining an adequate set of family history summary variables. Ignoring assay error will further diminish power and introduce a classification bias.

3. SIMULATION–BASED VALIDATION

In this section we assess the performance of the model of Section 2 given data simulated under three stylized ascertainment rules: population-based sampling, affected proband sampling, and high-risk sampling. We are interested in four issues: the accuracy of classification, the accuracy of penetrance estimates and their effect on classification accuracy, the sensitivity to different ascertainment rules, and the model’s performance in large samples.

We simulate three-member nuclear pedigrees consisting of parents and one offspring and consider only one heritable disease. This disease is assumed to be associated with a single disease-susceptibility gene with an autosomal-dominant mode of inheritance. Further, we assume that the allele frequency (prevalence) for each mutated variant of the disease gene is the same and that mutation-specific penetrances (the γ’s) are constant over age, that is, the disease is congenital.

We consider a population segregating a total of 30 unique mutations. Among these, 20 are MMs, of which 15 are nondeleterious and 5 are deleterious. The remaining 10 mutations are known deleterious mutations. Prevalence of each mutation is taken to be .002. The γ’s associated with nondeleterious mutations are generated from a beta(2, 18) distribution, whereas those associated with deleterious mutations are generated from a beta(8, 2) distribution.

Mirroring the setting of a gene characterization study, we assume that family histories are ascertained through the proband who has had a genetic test and for whom genotype is known. In the simulation study, the proband for each family is assumed to be the child, and the genetic test is assumed to be accurate. The disease status for each family member is observed.

Let xi denote the disease status of the ith family member and let g1 denote the proband’s genotype. The probability of observing a given family history conditional on the proband’s genotype is

where

The conditional probability P(g1|g2, g3) of the child’s genotype given the parental genotypes can be calculated from Mendel’s laws. The number of possible genotypes at a disease gene with M variants, ignoring genotypes of the form XY, is 1 + 2M. Hence P(g1 = i|g2, g3) can be written as a (1 + 2M) × (1 + 2M) matrix. The contribution of a family to the likelihood is P(x1, x2, x3|g1 = m). Because of the marginalization of unknown parental genotypes, this is a complicated polynomial involving the penetrances of all mutations. When the population frequency of each mutation is low, as is the case here, most of the information provided by the likelihood is about the penetrance of the mutation that the proband carries. Therefore, we approximate the family-specific contribution to the likelihood by a polynomial in the penetrance ρm of that mutation.

In this simulation study, we confine attention to three ascertainment schemes:

Population-based. Randomly sample family histories from the general population.

Affected proband. Ascertain families in which only the proband is diagnosed with disease.

High-risk. Sample disease-free families with probability .1, families with one diseasedmember with probability .5, those with two affected members with probability .7, and those with three affected members with probability .9.

These loosely reflect sampling schemes used in gene characterization studies. In practice, participants in family studies are usually collected under a more complex set of ascertainment rules, most closely resembling the high-risk scheme. For data ascertained via an affected proband, the ascertainment bias is easy to correct for explicitly using the conditional likelihood P(x2, x3|g1 = m, x1 = 1). Thus, for this mode of ascertainment, we also compare classification performance based on the ascertainment corrected and uncorrected likelihoods.

We simulated 10 replicate population-based datasets with sample size 4,000 and 10 replicates with sample size 6,000. For each replicate, we ascertained families according to the affected proband and high-risk rules. For data ascertained given an affected proband, we calculated both the ascertainment-corrected and uncorrected likelihoods; for the population-based and high-risk datasets, we used only the uncorrected likelihood [see (2)]. We used the priors, hyperpriors, and constraint described in Section 2, with the exception that we set ξ to 1 because we did not simulate testing error. We placed a beta(2, 2) prior on π, the proportion of deleterious missense mutations.

Table 1 summarizes the accuracy of penetrance estimates (estimates of the ρm’s) and of classification based on thresholding the posterior probability Pr(d(V) = 1|data) under the various simulation scenarios. The average high-risk sample size was 1,007, and the average affected proband sample size was 566 across the n = 4,000 replicates; these figures were 1,517 and 847 across the n = 6,000 replicates. The table also summarizes the bias and mean squared error (MSE) of penetrance estimates and of the probability that the variant is deleterious, Pr(d(V) = 1|data), as an estimate of d(V). In the case of penetrance, bias is higher under affected proband sampling than under high-risk sampling. This may be due to the absence of unaffected trios and unaffected tested individuals in the former samples. Estimation error as measured by MSE is due largely to bias; patterns evident bias are mirrored in the MSE. Note that bias and MSE under the uncorrected affected proband analysis apparently increase as a function of sample size.

Table 1.

Summaries of the Simulation Experiment by Ascertainment and Sample Size Scenario

| Average sample size | Penetrance bias | Classification bias | Penetrance MSE | Classification MSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 4,000 | |||||

| Population-based | 4,000 | .0497 | .0128 | .0039 | .0063 |

| Affected proband uncorrected | 566 | .3039 | .1638 | .1589 | .0707 |

| Affected proband corrected | 566 | .1647 | .1417 | .0497 | .0690 |

| High-risk | 1,007 | .1824 | .0586 | .0501 | .0248 |

| n = 6,000 | |||||

| Population-based | 6,000 | .0398 | .0144 | .0027 | .0104 |

| Affected proband uncorrected | 847 | .3273 | .1343 | .1763 | .0480 |

| Affected proband corrected | 847 | .1612 | .1170 | .0470 | .0477 |

| High-risk | 1,517 | .1799 | .0451 | .0489 | .0196 |

NOTE: Average sample size under each ascertainment scheme is calculated across replicates. Estimates of bias and MSE are presented for estimates of penetrance (ρm) and for the probability that the variant is deleterious, Pr(d(V) = 1|data), as an estimate of d(V) (“classification”). Bias and MSE estimates are averaged over variants and simulation replicates.

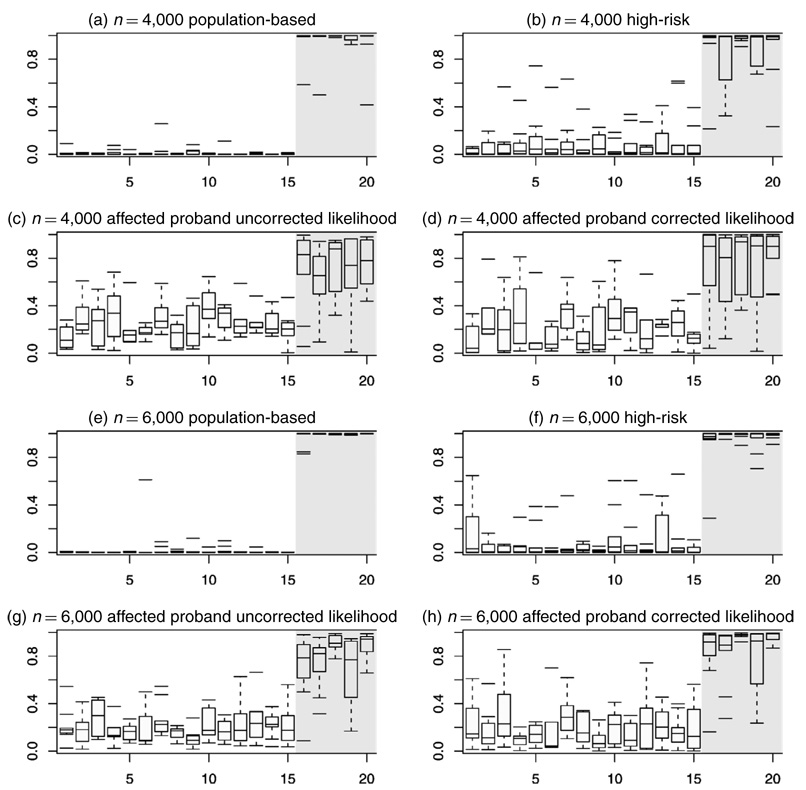

Although estimates of penetrance are clearly biased when unadjusted likelihoods are used with high-risk or affected proband data, the posterior probability that the mutation is deleterious remains an accurate classifier. Figure 1 displays boxplots of estimates of these probabilities across replicates for each missense mutation. For nondeleterious variants (indices 1–15 in the figure), these estimates, with few exceptions, cluster below .5, whereas those associated with the deleterious variants (indices 16–20) tend to cluster above .5. Estimates of MSE and bias in the estimated posterior probability that a variant is deleterious (Table 1) demonstrate that model estimates of the classification probability are robust to ascertainment scheme. Accuracy is greatest in population-based samples and worst in affected proband samples. In the latter case, the corrected likelihood leads to only a modest improvement over the uncorrected analysis.

Figure 1.

Boxplots of Pr(d(V)= 1) Across 10 Replicates for Each of the 20 MMs. MMs are indexed along the x-axis, with indices 1–15 corresponding to the nondeleterious variants and indices 16–20 corresponding to the deleterious variants. Panels (a)–(d) summarize the 10 n = 4,000 replicates, and (e)–(h) summarize the 10 n = 6,000 replicates. Panels (a) and (e) summarize results from analysis of the full the population-based samples, panels (b) and (f) summarize analysis of the high-risk subsamples, and the remaining panels summarize the affected proband analysis. In (c) and (g) the likelihoods are not corrected for the ascertainment mechanism, whereas in (d) and (h) the likelihoods are corrected.

Table 2 summarizes misclassification rates when classification is determined by thresholding the estimated Pr(d(V) = 1|data) at .5. If sampling is population-based, then classification is very accurate. Furthermore, under high-risk and affected proband ascertainment, error rates are higher but classification accuracy is still good. Under the latter, there is little difference between using the corrected and uncorrected likelihoods, but classification is apparently more accurate using the uncorrected likelihood. This is probably because the ascertainment correction results in a loss of information and thus greater uncertainty in penetrance estimates. Note also that classification performance improves as the size of the dataset increases for all modes of ascertainment considered, even for the uncorrected affected proband analysis, where the accuracy of the penetrance estimates worsens with sample size.

Table 2.

Proportion of Missense Mutations Incorrectly Classified Across Simulation Replicates

| Sample size | Population-based | High-risk | Affected proband, no likelihood correction | Affected proband, likelihood correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4,000 | .005 | .046 | .125 | .153 |

| 6,000 | .005 | .026 | .070 | .094 |

In summary, the simulation study shows that in the foregoing scenarios, (1) the hierarchical classification model accurately classifies missense mutations, (2) the model does so even when the data are not population-based and when the likelihood does not implicitly correct for ascertainment, (3) the latent classification variable is robust to ascertainment bias even while the penetrance parameter is not, and (4) not surprisingly, classification accuracy increases with sample size.

4. APPLICATION TO MISSENSE MUTATIONS AT BRCA1 AND BRCA2

In this section we apply the hierarchical classification model to studying a dataset of MMs of the breast cancer susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 identified within a study of women at high risk for breast and ovarian cancer. This analysis involves complexities not present in the simulation study. In particular, the genetic model is of two loci, each of which predisposes carriers to elevated risk of two diseases (breast and ovarian cancer) with associated age-dependent penetrance functions. Furthermore, individual family histories are typically larger and more complex and genetic assay error complicates classification. In what follows, we describe the dataset, detail a penetrancemodel and present analysis results.

Our dataset comprises a total of 280 moderate-sized family histories, most of which (277) were collected at the Duke University Center. Each was ascertained through a proband who was tested for mutations at BRCA1 and BRCA2. There are probands carrying two mutations on the same gene, although none of these mutations appear independently on probands in our dataset. (More details are available in Skinner et al. 2002 and Zhou 2002.) We augment this dataset with three families of probands who tested positive with BRCA1 MM R841W from the study of Barker et al. (1996) for comparison; these three families are believed to be ascertained in a similar way as those from Duke. Family histories include the breast and ovarian cancer status of all first- and second-degree relatives of the proband as well as each individual’s age and age(s) at diagnosis, if affected. Most of the identified deleterious mutations are at BRCA1, whereas most of the identified MMs are at BRCA2. Among the 280 probands, 59 tested positive for known deleterious mutations at either BRCA1 or BRCA2, with 41 carrying 1 of the 24 unique BRCA1 mutations identified in the sample and 18 carrying 1 of 15 unique BRCA2 mutations. A further 16 (29) probands tested positive for 1 of 9 (26) unique BRCA1 (BRCA2) MMs. The remaining 174 probands tested negative for any form of mutation at BRCA1 or BRCA2.

Apparent differences in familial disease phenotype between families of deleterious mutation-positive individuals, MM-positive individuals and MM-negative individuals in this dataset are subtle. Simple summaries of family history clearly cannot provide the necessary sensitivity to classify the disease causality of MMs in this kind of study. What is needed is a low-dimensional summary of family history to use as a classification variable, one that captures the critical features in the family history.

Although the raw data show differences in family histories according to the genetic test result of the proband, a genetic model is needed to recover and fully exploit the subtle differences exhibited in the limited family histories associated with each mutation. To accomplish this discrimination, we use a full likelihood-based approach that takes into account the exact structure of the pedigree, the ages of its members, the breast and ovarian cancer status of its members, and the ages of diagnosis of affected members. Disease incidence and age at diagnosis enter the model through site- and mutation-specific penetrance functions. Because family histories in our study are all moderate in size, specifying a fully parameterized mutation-specific penetrance model is likely to overfit the data and miss the main differences between family histories associated with individual mutations. As an alternative, we implement a simple one-parameter penetrance model.

Various studies have focused on penetrance of breast and ovarian cancers among carriers of deleterious BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations (Easton et al. 1995, 1997; Ford et al. 1998; Struewing et al. 1997; Fodor et al. 1998). This literature serves as the foundation for a simple penetrance model. We take as our starting point the smooth parametric estimates distributed with the BRCAPRO carrier probability model (Parmigiani 2002; Parmigiani et al. 1998) and described by Iversen, Parmigiani, Berry, and Schildkraut (2000). These estimates are based on a meta-analysis of the data reported by Ford et al. (1998) and Struewing et al. (1997).

Let ρv,s(a) denote the mutation-specific penetrance of disease s at age a for variant ν, let ρs,l(a) denote the penetrance of disease s at age a among known deleterious mutations at locus (i.e., BRCAl) estimated from previous studies, and let ρs(a) denote the phenocopy rate estimated from previous studies. A natural choice for the penetrance model is

In this parameterization, the baseline hazard is that associated with carriers of known deleterious mutations in the general population and γν/(1 - γν) is the hazard ratio associated with variant ν. When γν = 0, variant ν is protective of disease [ρν,s(a) = 0 for all a], when γν = .5, it is indistinguishable from a deleterious polymorphism, and when γν = 1, it is fully penetrant [ρν,s(a) = 1 for all a]. Although parameter γν is assumed to be independent of age and cancer site to accommodate limited sample size, the overall mutation-specific penetrance is age dependent. This parameterization of penetrance indexes a family of penetrance curves by a one-dimensional variable with support [0, 1]. Numerous other families of curves may be obtained in a similar fashion (Zhou 2002), but sensitivity analysis of the classification model to this choice is beyond the scope of this article.

The conditional likelihood based on any of these penetrance models can be calculated as described in the simulation section. A factor that complicates this calculation for the high-risk breast cancer data is that family histories are larger, consisting of all first- and second-degree relatives of the proband, and vary in structure. Computing the likelihood requires summing over all possible combinations of genotype among family members conditional on the proband’s genotype. This calculation is performed through a modified version of the software application BRCAPRO (Berry, Parmigiani, Sanchez, Schildkraut, and Winer 1997; Parmigiani, Berry, and Aguilar 1998). Briefly, BRCAPRO calculates the probability that an individual is a carrier of a deleterious BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation given her family history of breast and ovarian cancer among first- and second-degree family members. BRCAPRO assumes an independent autosomal-dominant mode of transmission for BRCA1 and BRCA2 and takes as inputs prevalence of deleterious BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and penetrance of breast and ovarian cancer among the two classes of mutation carriers and among carriers of benign polymorphisms. We modified the software to calculate the likelihood of the observed family history given mutation prevalence and disease penetrance and the aforementioned genetic model.

We constructed the classification model as described in Section 2. We used a beta prior with parameters (2, 2) for π. We developed the prior for ξ assuming that the sensitivity of the genetic test single strand conformational polymorphism (SSCP) was about 65% to 75% and that the prevalence of mutations in the sample is between 30% and 50%. Using Bayes’ rule, a relatively conservative choice for ξ would be around .7. Hence we chose a beta distribution with parameters (7, 3). Finally, we placed uniform(1, 100) hyperpriors on α1, β1, α2, and β2.

We sampled the posterior distribution of model parameters using Gibbs sampling. In fitting the model, we carried out 200,000 iterations, retaining every 10th. Trace plots of the posterior samples appeared stationary and the chains passed the Heidelberger and Welch (1983) test for stationarity. Furthermore, the samples were declared sufficient to estimate the 2.5th percentile of any of the marginal posteriors within an accuracy of .5% with probability 95% based on the Raftery and Lewis (1996) diagnostic.

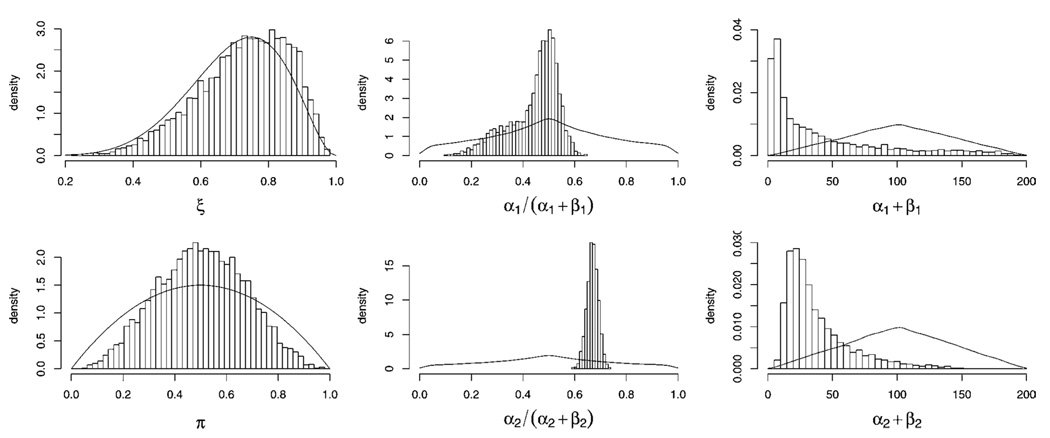

Histograms of marginal posterior samples of model parameters are in Figure 2 with their respective priors. The data are very weakly informative for π and virtually uninformative for ξ. This reflects the fact that it is difficult to locate the anchor populations (carriers of benign polymorphisms and carriers of deleterious mutations) given data obtained through high-risk ascertainment. The data are, however, informative for parameters α1, β1, α2, and β2. We estimate the posterior mean of the distribution of nondeleterious γ’s to be E(α1/(α1 + β1)|data) = .44 with 95% equal-tailed interval (.22, .57) and estimate the posterior mean of the distribution of deleterious γ’s to be E(α2/(α2 + β2)|data) = .67 with 95% equal-tailed interval (.62, .71).

Figure 2.

Histograms of Posterior Samples of Model Parameters. Prior distributions on model parameters are plotted as solid lines.

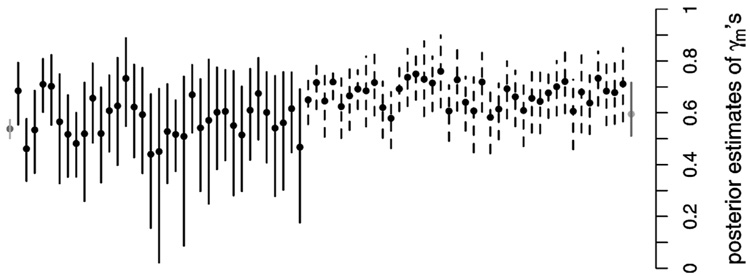

Estimated posterior means of the γν’s and associated 90% equal-tailed posterior intervals are plotted in Figure 3 as solid dots. Intervals associated with MMs are plotted as solid lines, those of known deleterious mutations as dashed lines, and those associated with variants 0 (leftmost on the plot) and 1 (rightmost) as gray lines. Posterior estimates of mutation-specific γν’s vary widely. Those with high Pr(d(ν) = 1|data) (Fig. 4) have point and interval estimates similar in location and range to those associated with the known deleterious variants (dashed intervals); see, for example, the variants plotted second, fifth, and sixth from the left. Those with low Pr(d(ν) = 1|data) have point estimates located closer to the wild-type point estimate (far left) and tend to reflect greater uncertainty.

Figure 3.

Posterior Means and 90% Equal-Tailed Intervals of the γν’s. Intervals associated with missense mutations are plotted as solid lines, those associated with known deleterious variants are plotted as dashed lines, and those associated with the wild-type variant(s) 0 (left) and the unobserved, common disease associated variant 1 (right) are plotted as gray lines.

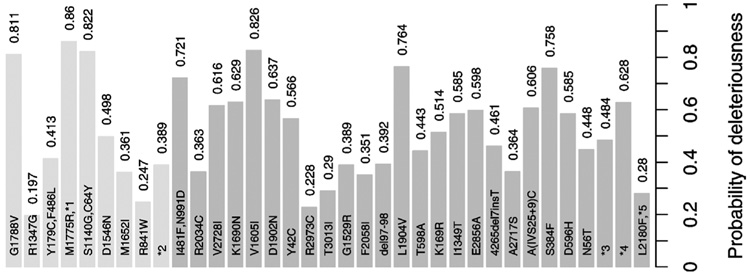

Figure 4.

Posterior Probabilities Pr(d(ν)= 1|data) for the MMs. Missense mutations at BRCA1 are lightly shaded at the left of the plot, and those at BRCA2 are darkly shaded on the right. Four mutations occurring at the intron region of the gene are denoted by “*n.”

The posterior probabilities Pr(d(ν) = 1|data) associated with each MM are shown in Figure 4. Mutations denoted as “*n” are VUSs from an intronic region. The estimated probabilities of disease causality range from .197 to .860. Mutations (M1775R, *1), (S1140G, C64Y), and G1788V at BRCA1 and mutations V1605I and L1904V at BRCA2 have the strongest association with disease. The association is much weaker for R1347G at BRCA1 and for R2973C at BRCA2. BRCA1 variant R841W, studied by Barker et al. (1996) and Petersen et al. (1998), is less strongly associated with disease than most of the other variants analyzed here. In contrast, the former group found “strong evidence” for disease association, and the latter group noted that the variant is “likely disease-causing.”

5. DISCUSSION

In this study we have developed a Bayesian hierarchical method to study disease causality of MMs. This method provides a framework for simultaneously evaluating the disease association of a group of mutations and allows for a systematic comparison of the evidence of causality from observed family histories. This systematic comparison allows us to present results that are useful to both genetic counselors and molecular biologists, while providing insights into gene function through an analysis of high-risk family history data.

Family studies of Mendelian disease are increasingly common. Many have suggested that among mutation carriers, there is variation in disease susceptibility and age at disease onset. Possible reasons for this kind of variation may include genetic factors, environmental factors, or both. Althought there have been numerous studies focusing on environmental modifiers of Mendelian disease, few have been aimed at evaluating variability in phenotypic exemplification associated with different variants at a common locus. The primary reasons for this are the lack of sufficiently large variant-specific samples for accurate penetrance estimation and difficulties in correcting biases induced by data ascertainment. Our method builds a framework for analyzing this kind of dataset.

This method provides a meaningful evaluation of the disease causality of a group of MMs because it compares them with mutations that have a known association with disease and with those that have no functional change in the protein, that is, common polymorphisms. This evaluation is model-based and is made with respect to a homogeneous (with respect to ascertainment) group of data. In our analysis we assume that all polymorphisms of the disease gene(s) under study are not associated with disease. If this assumption is violated, then our method may underestimate the disease causality of the MMs if one or more polymorphisms is indeed associated with increased risk of disease. This also applies to the situation where residual familial correlations not related to the locus under study are present, because it is more likely that the negatives harbor a deleterious mutation on another locus. The penetrance model that we use for classification is simple, involving only one parameter, and is based on currently available estimates of penetrances. More realistic models of penetrance would involve more flexible, higher-dimensional families of penetrance curves but would require larger datasets for estimation. Substituting a more sophisticated family of penetrance curves would, however, require only minimal changes to the model. Improved estimates of penetrance and phenocopy rate may also improve the method’s reliability.

There are a number of opportunities for expanding the study of MMs at BRCA1 and BRCA2 to encompass larger sets of MMs. The NCI’s Cancer Genetics Network, for example, maintains several large family history datasets with structure similar to that analyzed here. These datasets comprise samples collected at multiple centers, under different modes of ascertainment. The model that we have described could be applied to this type of dataset after a modification to hierarchically model the multiple centers and modes of ascertainment. The encouraging results that we obtained on a relatively small dataset suggests that our method will perform extremely well on large multicenter datasets, providing critically important information on disease risk for genetic counselors, molecular biologists, and, most important, the carriers of MMs themselves.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ken Kinzler for providing input on our use of genetic terminology. This work was funded in part by the National Cancer Institute through the Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Breast Cancer at Duke University (P50 CA68438), the Innovative Pilot Research in Cancer Control Science Program at Duke University (CA14236SUB38), and the Cancer Genetics Network at Duke University (U24 CA78157), and at Johns Hopkins University (U24 CA78148).

REFERENCES

- Abel L, Bonney GE. A Time-Dependent Logistic Hazard Function for Modeling Variable Age of Onset in Analysis of Familial Diseases. Genetic Epidemiology. 1990;7:391–407. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370070602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DF, Almeida ER, Casey G, Fain PR, Liao S-Y, Masunaka I, Noble B, Kurosaki T, Anton-Culver H. BRCA1 R841W: A Strong Candidate for a Common Mutation With Moderate Phenotype. Genetic Epidemiology. 1996;13:595–604. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2272(1996)13:6<595::AID-GEPI5>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DA, Parmigiani G, Sanchez J, Schildkraut J, Winer E. Probability of Carrying a Mutation of Breast-Ovarian Cancer Gene BRCA1 Based on Family History. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1997;89:227–238. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIC. National Institutes of Health, Breast Cancer Information Core: An Open-Access On-Line Breast Cancer Mutation Data Base. available at http://www.nhgri.nih.gov/Intramural_research/Lab_transfer/Bic/.

- Boehnke M, Greenberg DA. The Effects of Conditioning on Probands to Correct for Multiple Ascertainment. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1984;36:1298–1308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonney GE. Ascertainment Corrections Based on Smaller Family Units. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1998;63:1202–1215. doi: 10.1086/302057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton RGH, Scriver CR. Proof of Disease-Causing Mutation. Human Mutation. 1998;12:1–3. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)12:1<1::AID-HUMU1>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DV. Ascertainment Models Incorporating Effects of Variable Age of Onset. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1994;53:340–347. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320530407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton DF, Ford D, Bishop DT The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Breast and Ovarian Cancer Incidence in BRCA1-Mutation Carriers. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1995;56:265–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton DF, Steele L, Fields P, Ormiston W, Averill D, Daly PA, McManus R, Neuhausen SL, Ford D, Wooster R, Cannon-Albright LA, Stratton MR, Goldgar DE. Cancer Risks in Two Large Breast Cancer Families Linked to BRCA2 on Chromosome 13q12-13. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1997;61:120–128. doi: 10.1086/513891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston RC. Ascertainment and Age of Onset in Pedigree Analysis. Human Heredity. 1973;23:105–112. doi: 10.1159/000152561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston RC. Twixt Cup and Lip: How Intractable Is the Ascertainment Problem? American Journal of Human Genetics. 1995;56:15–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston RC, Bonney GE. Sampling Considerations in the Design and Analysis of Family Studies. In: Rao DC, Elston RC, Kuller LH, editors. Genetic Epidemiology of Coronary Heart Disease—Past, Present, and Future. New York: Alan R. Liss; 1984. pp. 349–371. [Google Scholar]

- Elston RC, George VT. Age of Onset, Age at Examination and Other Covariates in the Analysis of Family Data. Genetic Epidemiology. 1989;6:217–220. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370060138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston RC, Stewart J. A General Model for the Genetic Analysis of Pedigree Data. Human Heredity. 1971;21:523–542. doi: 10.1159/000152448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewens WJ, Shute NCE. A Resolution of the Ascertainment Sampling Problem. I, Theory. Theoretical Population Biology. 1986;30:388–412. doi: 10.1016/0040-5809(86)90042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RA. The Effect of Methods of Ascertainment Upon the Estimation of Frequencies. Annals of Eugenics. 1934;6:13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fodor FH, Weston A, Bleiweiss IJ, McCurdy MM, Walsh LD, Tartter PI, Brower ST, Eng CM. Frequency and Carrier Risk Associated With Common BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish Breast Cancer Patients. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1998;63:45–51. doi: 10.1086/301903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M, Narod S, Goldgar D, Devilee P, Bishop DT, et al. Genetic Heterogeneity and Penetrance Analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 Genes in Breast Cancer Families. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1998;62:676–689. doi: 10.1086/301749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes WD, Hodgson SV, editors. Inherited Susceptibility to Cancer: Clinical, Predictive and Ethical Perspectives. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gauderman WJ, Thomas DC. Censored Survival Models for Genetic Epidemiology: A Gibbs Sampling Approach. Genetic Epidemiology. 1994;11:171–188. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370110207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George VT, Elston RC. Ascertainment: An Overview of the Classical Segregation Analysis Model for Independent Sibships. Biometrics Journal. 1991;33:741–753. [Google Scholar]

- Grann VR, Panageas KS, Whang W, Antman KH, Neugut AI. Decision Analysis of Prophylactic Mastectomy and Ophorectomy in BRCA1-Positive or BRCA2-Positive Patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1998;16:979–985. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes F, Cayanan C, Barilla D, Monteiro NA. Functional Assay for BRCA1: Mutagenesis of the COOH-Terminal Region Reveals Critical Residues for Transcription Activation. Cancer Research. 2000;60:2411–2418. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidelberger P, Welch P. Simulation Run Length Control in the Presence of an Initial Transient. Operations Research. 1983;31:1109–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen ES, Jr, Parmigiani G, Berry D, Schildkraut J. Genetic Susceptibility and Survival: Application to Breast Cancer. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2000;95:28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft P, Thomas DC. Bias and Efficiency in Family-Based Gene Characterization Studies: Conditional, Prospective, Retrospective, and Joint Likelihoods. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2000;66:1119–1131. doi: 10.1086/302808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li FP. Identification and Management of Inherited Cancer Susceptibility. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1995;3:297–300. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s8297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Thompson E. Semiparametric Estimation of Major Geneand Family-Specific Random Effects for Age of Onset. Biometrics. 1997;53:282–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch HT, de la Chapelle A. Genetic Susceptibility to Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Medical Genetics. 1999;36:801–818. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki Y, Swenson J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, et al. A Strong Candidate for the Breast and Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility Gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266:66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton NE. Genetic Tests Under Incomplete Ascertainment. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1959;11:1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddoux C, Struewing JP, Clayton CM, et al. The Carrier Frequency of the BRCA2 6174delT Mutation Among Ashkenazi Jewish Individuals Is Approximately 1% Nature Genetics. 1996;14:188–190. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmigiani G. BRCAPRO. website http://astor.som.jhmi.edu/BayesMendel/brcapro.html.

- Parmigiani G, Berry DA, Aguilar O. Determining Carrier Probabilities for Breast Cancer Susceptibility Genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1998;62:145–158. doi: 10.1086/301670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen GM, Parmigiani G, Thomas D. Missense Mutations in Disease Genes: A Bayesian Approach to Evaluate Causality. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1998;62:1516–1524. doi: 10.1086/301871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz D. A Pseudolikelihood Approach to Correcting for Ascertainment Bias in Family Studies. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1996;59:726–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE, Lewis SM. Implementing MCMC. In: Gilks WR, Richardson S, Spiegelhalter DJ, editors. Markov Chain Monte Carlo in Practice. Spiegelhalter, London: Chapman & Hall; 1996. pp. 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Boland CR, Hamilton SR, Henson DE, Jass JR, et al. A National Cancer Institute Workshop on Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer Syndrome: Meeting Highlights and Bethesda Guidelines. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1997;89:1758–1762. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.23.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer S. Maximum Likelihood Estimators for Incorrect Models, With an Application to Ascertainment Bias for Continuous Characters. Theoretical Population Biology. 1990;38:351–366. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner CS, Schildkraut JM, Calingaert BDB, Marcom PK, Sugarman J, Winer EP, Iglehart JD, Futreal PA, Rimer BK. Pre-Counseling Education Materials for BRCA Testing: Does Tailoring Make a Difference? Genetic Testing. 2002;6:93–105. doi: 10.1089/10906570260199348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struewing JP, Hartge P, Wacholder S, Baker SM, Berlin M, McAdams M, Timmerman MM, Brody LC, Tucker MA. The Risk of Cancer Associated With Specific Mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Among Ashkenazi Jews. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;336:1401–1408. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199705153362001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DC. Design of Gene Characterization Studies: An Overview. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 1999;26:17–23. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallon-Christersson J, Cayanan C, Haraldsson K, Loman N, Bergthorsson JT, et al. Functional Analysis of BRCA1 c-Terminal Missense Mutations Identified in Breast and Ovarian Cancer Families. Human Molecular Genetics. 2001;10:353–360. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.4.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkitaraman AR. Functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in the Biological Response to DNA Damage. Journal of Cell Science. 2001;114:3591–3598. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieland VJ, Hodge SE. Inherent Intractability of the Ascertainment Problem for Pedigree Data: A General Likelihood Framework. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1995;56:33–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Kinzler K. The Genetic Basis of Human Cancer. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss KM. Genetic Variation and Human Disease. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Winter RM. The Estimation of Phenotype Distributions From Pedigree Data. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1980;7:349–371. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320070415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, Swift S, Seal S, Mangion J. Identification of the Breast Cancer Susceptibility Gene BRCA2. Nature. 1995;378:789–792. doi: 10.1038/378789a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic Testing—Present and Future. Science. 2000;289:1890–1892. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5486.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. Classification of Missense Mutations of Disease Genes. Duke University; 2002. unpublished doctoral thesis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]