Abstract

Over the last 20 years, our understanding of the pathophysiology and symptomatology of men with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) has become increasingly more sophisticated. With this increase in sophistication, our utilization of various medical therapies, either alone or in combination, has also increased the understanding of the roles of individual medications, combinations of medications, and the benefits of different types of intervention. The rapid decline of the use of transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) and other surgical procedures for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) in the 1990s is due in part to the introduction of medical therapy. This article reviews the current state of medical therapy for men with LUTS and highlights its promises and its current limitations.

Key words: Lower urinary tract symptoms, Benign prostatic hyperplasia, Medical therapy, Alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers, 5-Alpha-reductase inhibitors

Our understanding of the relationship between men with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) has significantly changed recently. Prior to the introduction of medical therapy for what was then called prostatism, or simply clinical BPH, a physician’s response to a man’s complaint about LUTS was uniform. At a certain age, these symptoms were assumed to be due to BPH and, thus, a transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) was recommended. A first major change involved the nomenclature and the abandonment of the term prostatism, which draws undue attention to the prostate and does not accurately reflect that many of these symptoms are not necessarily due to the prostate, but may be due to bladder conditions as well. Thus, the term lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) was introduced. It is understood that in many elderly men, LUTS are due to BPH, but as this is not necessarily so, a hybrid term was utilized in the literature and in clinical jargon, LUTS due to clinical BPH, which assumes that the most common cause for men presenting with LUTS would be a hyperplasia of the prostate. BPH, however, is simply a histological term that may or may not be associated with LUTS, benign prostatic enlargement (BPE), or bladder outlet obstruction (BOO). BPH, BPE, and BOO may all exist in one patient, whereas a second patient has BPH only, a third patient has BPH with BPE, and a fourth patient has BPH with BOO, all without significant prostatic enlargement. The presence or absence of bothersome symptoms is independent of the conditions discussed above.

In recent years, awareness has also arisen that, like women, men also suffer from overactive bladder symptoms (OAB). The storage symptoms of OAB, consisting of frequency, urgency, and urge urinary incontinence, are just as bothersome, if not more bothersome, to patients, compared to typical voiding symptoms, such as hesitancy, straining, intermittency, and sensation of incomplete emptying. Nocturia also belongs in the category of storage symptoms and is often the driving force when patients seek medical advice and treatment.

These changes in our thinking have led to a multitude of changes in the nomenclature, and now, the best term to describe the constellation of voiding, storage, and postmicturition symptoms would be male LUTS with or without OAB. The presence or absence of histological hyperplasia with or without BPE or BOO is noted independently, as it may have consequences for appropriate treatment choices.

These changes in nomenclature occurred during a time of fundamental change in our therapeutic approach to men presenting with LUTS. Prior to the 1980s, TURP was the only alternative available other than watchful waiting and conservative management. The 1990s saw the introduction of several alpha1-adrenergic receptor blockers and two 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors (5ARIs). During much of the 1990s, physicians utilized both classes of drugs indiscriminately and it was only recently that the recognition grew that these drugs should be used in a differentiated manner. Alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers are suitable for quick and effective symptom relief while not actually impacting the natural history of the disease, whereas 5ARIs have been proven to be quite ineffective in men with smaller prostates and lower prostate-specific antigen (PSA) values while having reasonable symptom improvement efficacy in men with larger glands and higher PSAs. In this latter group, alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers also interfere with the natural history of the disease by preventing further prostate growth and reducing the risk of acute urinary retention (AUR) and the subsequent need for surgery.

The current decade brought new revelations. First, studies such as the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) trial demonstrated that the combination of alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers and 5ARIs add additional efficacy to the management of patients particularly at risk for progression. 1 Second, the growing recognition of the importance of OAB symptoms in men led to the utilization of antimuscarinic agents. After initial trials demonstrated that the addition of antimuscarinic agents to alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers was both safe and effective, a randomized, placebo-controlled trial recently demonstrated superior efficacy of such a combination in men with both voiding and storage symptoms who would qualify for both a BPH and an OAB trial.2

Over the last 20 years, our understanding of the pathophysiology and symptomatology of men with LUTS has become increasingly more sophisticated. With this increase in sophistication, our utilization of various medical therapies, either alone or in combination, has also increased the understanding of the roles of individual medications, combinations of medications, and the benefits of different types of intervention.

This article reviews the current state of medical therapy for men with LUTS and highlights its promises and its current limitations.

Aging of the Population and Impact on Medical Care

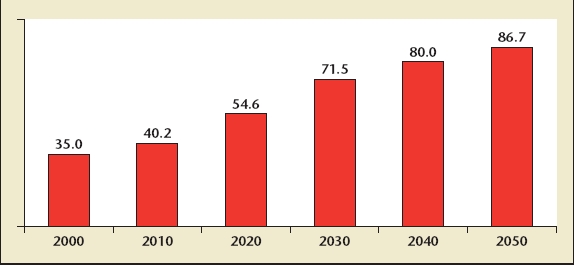

In December 2005, the US National Institute on Aging and the US Census Bureau released a report entitled 65 + in the United States: 2005.3 This report examined the impact of the significant increase in life expectancy, as well as the impact of the Baby Boom generation upon demographics in the United States and elsewhere. This generation is currently between the ages of 40 and 60, and by the year 2020, will be between the ages of 55 and 75, that is, at a prime age for the development of prostate conditions and LUTS. Both the aging of the population and the peculiar phenomenon of the Baby Boom Generation will lead, by some estimates, to a doubling of the population aged 65 and over in the United States between the year 2000 and the year 2030, specifically an increase from 35 million to 71.5 million (Figure 1). Such increase in the population aged 65 and over in the United States and other developed countries is matched or even exceeded in developing countries. In fact, estimates would suggest that the population aged 65 and older in developing countries might triple during the same period.

Figure 1.

US population aged 65 years and over, 2000 to 2050. Reprinted with permission from He W et al.3

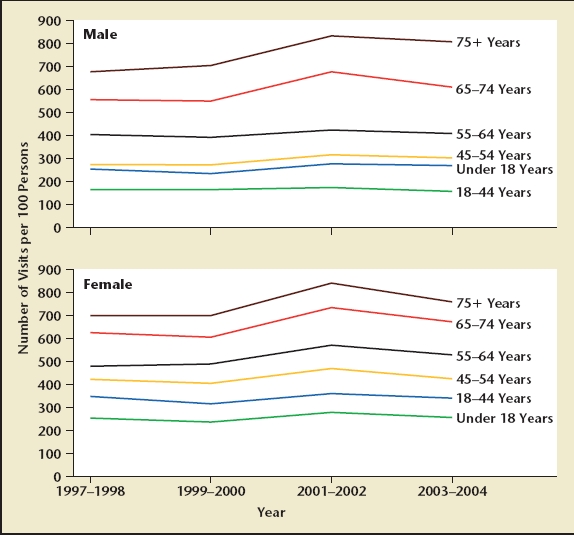

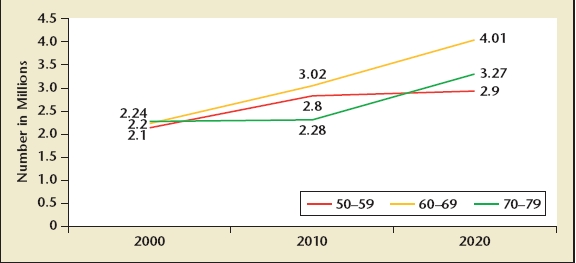

Physician and hospital outpatient visits are more common in men and women aged 65 and older compared to those under the age of 65 (Figure 2). Prostate conditions such as LUTS, BPH, and prostate cancer are diseases of aging men, and there will be a significant increase in the number of men seeking advice for LUTS, BPH, BPE, BOO, and prostate cancer in the upcoming decades. Based on estimates made by Steve Jacobsen in 1995 following the publication of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) guidelines for BPH,4 the total population eligible for treatment for LUTS and BPH will increase from 6.5 to 10.3 million from the year 2000 to 2020 (Figure 3).5

Figure 2.

Physician office and hospital visits by age for men and women, 1997 to 2004. Reprinted with permission from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2006; Figure 22.

Figure 3.

US men eligible for benign prostatic hyperplasia treatment, 2000 to 2020. Based on 1994 Agency for Health Care Policy and Research guidelines and Olmsted County, Minnesota. International Prostate Symptom Score greater than 7 and Qmax is less than 15 mL/s. Data from Jacobsen SJ et al.5

Efficacy and Safety of Current Medication

The majority of available data regarding efficacy and safety of medical therapy for men with LUTS and clinical BPH consists of randomized, placebo-controlled studies regarding the use of various alpha1-adrenergic receptor blockers and 5ARIs. Recently, other classes of medications have entered the scientific literature and clinical use, such as antimuscarinic/anticholinergic agents and phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE-5) inhibitors. An excellent review of the efficacy and safety of medications (although slightly dated) is the 2003 American Urological Association (AUA) update of the BPH guidelines, which summarizes the state of our knowledge regarding the treatment for men with LUTS and BPH, including minimally invasive and surgical treatments6 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Outcomes of Medical Therapies From American Urological Association’s Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Guidelines Update

| Peak Flow Rate | QoL Question | BPH Impact | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUA/IPSS |

(Qmax) |

Score |

Index |

|||||||||

| 3–9 | 10–16 | >16 | 3–9 | 10–16 | >16 | 3–9 | 10–16 | 3–9 | 10–16 | |||

| Therapy | Months | Months | Months | Months | Months | Months | Months | Months | Months | Months | ||

| Alpha blockers | ||||||||||||

| Alfuzosin | −4.44 | 2.05 | −1.10 | |||||||||

| Doxazosin | −5.10 | −5.63 | 3.11 | 2.98 | 1.90* | −1.25 | −1.47 | −2.00 | −2.47 | |||

| Tamsulosin | −4.63 | −7.53* | 1.85 | 1.86* | −1.43 | |||||||

| Terazosin | −6.22 | −5.99 | 2.51 | 1.94 | 2.61* | −1.70* | −1.37 | −1.45* | −2.09 | |||

| Hormonal | ||||||||||||

| Finasteride | −3.44 | −3.40 | −2.37 | 2.11 | 1.66 | 1.95 | −0.75 | −0.87 | −1.50 | −1.21 | ||

| Combinations | ||||||||||||

| Alfuzosin/finasteride | −6.10* | 2.30* | ||||||||||

| Doxazosin/finasteride | −5.64 | −6.53 | 3.96 | 3.38 | −1.15 | −1.57 | −2.20 | −2.57 | ||||

| Terazosin/finasteride | −5.90* | −6.21* | 3.50* | 2.63 | −1.55* | −2.03 | ||||||

| Placebo | −2.44* | −2.33* | −1.03* | 0.86* | 0.48* | 0.48* | −0.65* | −0.67* | −1.00* | −0.97* | ||

Numbers without asterisks are based on randomized, controlled trial (RCT) results with placebo controls.

Based on single-arm analyses; no RCT data available.

AUA. American Urological Association; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; IPPS, International Prostate Symptom Score; QoL, quality of life. Reprinted with permission from The Journal of Urology, Volume 170, AUA Practice Guidelines Committee, AUA Guideline on Management of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (2003). Chapter 1: Diagnosis and Treatment Recommendations, p. 542, Copyright Elsevier 2003.6

Single Medications

Alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers. The alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers were the first class of medication introduced into clinical practice for use in men with prostatism or BPH.7–9 Since the late 1980s, 4 alpha1-adrenergic receptor blockers have been introduced and are currently in use in the US market: alfuzosin, doxazosin, tamsulosin, and terazosin. Whereas doxazosin and terazosin require dose titration due to adverse effects such as dizziness and hypertension, both tamsulosin and alfuzosin do not require titration, and are thus easier to use in clinical practice (Table 2). Doxazosin is currently available under the brand name Cardura® XL (Pfizer Inc, New York, NY) as a slow-release formulation (4 mg or 8 mg) not requiring dose titration.10 It is known that of the alpha1-adrenergic receptor subtypes, the alpha1A receptor is most dominant in the prostate and bladder neck area, whereas the B receptor is present to a lesser degree in the detrusor muscle. The blockage of the B receptor is thought to be more responsible for the treatment of detrusor overactivity and storage symptoms. The alpha1D receptor is also present in the spinal cord; the alpha1B receptor subtype is to be avoided as it is present in the capacity vessels in older patients, and is possibly responsible for hypotension and undesirable cardiovascular side effects.11

Table 2.

Comparison of Available Alpha1-Adrenergic Receptor Blockers

| Agent | Dosing | Titration | Uroselective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terazosin (Hytrin®) | 1 mg, 2 mg, 5 mg | + | |

| 10 mg, 20 mg | |||

| Doxazosin (Cardura®) | 1 mg, 2 mg, 4 mg, | + | |

| 8 mg, 16 mg | |||

| Doxazosin (Cardura® | 4 mg | + | |

| XL) | 8 mg | One step | |

| Tamsulosin (Flomax®) | .4 mg, | +/− | Relative affinity |

| .8 mg | for alpha1A receptors | ||

| over alpha1B | |||

| Alfuzosin (Uroxatral®) | 10 mg | − | Highly diffused in |

| prostatic tissue vs | |||

| serum |

Product information: Hytrin®, © Abbott Laboratories (Abbott Park, IL); Cardura® and Cardura® XL, © Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY); Flomax®, © Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Ridgefield, CT); Uroxatral®, data on file, sanofi-aventis (Bridgewater, NJ).

The AUA guidelines suggest that the efficacy in terms of symptom and flow-rate improvement, as well as the impact upon quality of life, is similar for all alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers. In fact, Table 1 suggests that, on average, the symptom score improvement between 3 and 9 months ranges from 4.4 to 6.2 points, and at 10 to 16 months ranges from 5.6 to 7.5 points for the various alpha blockers. In the interim, longer-term data have become available through the MTOPS study (doxazosin) and the Alfuzosin Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study (ALTESS).1,12 The MTOPS and ALTESS studies suggest that in those patients who stay on medical therapy, alpha blockers retain symptomatic effect to efficacy at a level commensurate to that observed in the short and immediate term.

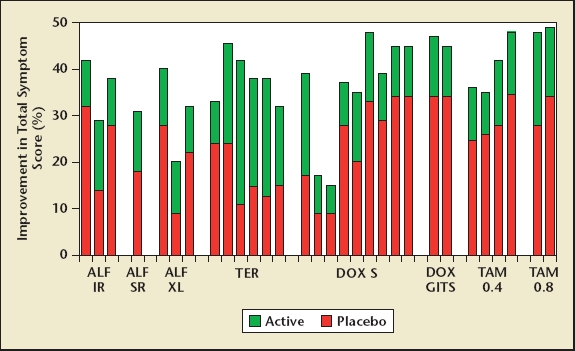

However, the effect that alpha blockers have on the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) is found in a significant proportion of the corresponding placebo arm, and thus is not due to the specific action of the alpha blocker on the bladder, prostate, or the peripheral nervous system and spinal cord (Figure 4). In a wide variety of studies utilizing alfuzosin in immediate-release, slow-release, or extended-release form; terazosin; doxazosin as an immediate-release or gastrointestinal therapeutic system (GITS) formulation; and for both tamsulosin .4 and .8 mg, the additional benefit of an alpha blocker over placebo in terms of the percentage improvement in IPSS is approximately 10% to 15%, with no major discernible difference among the different types of alpha blockers.

Figure 4.

Efficacy of alpha1-adrenergic receptor blockers with corresponding placebo response expressed as percentage improvement in International Prostate Symptom Score. Additional benefit with alpha blockers over placebo is about 10% to 15%. Total number of patients: alfuzosin (ALF), n = 2208; terazosin (TER), n = 3229; doxazosin (DOX), n = 3947; and tamsulosin (TAM), n = 1331. GITS, gastrointestinal; IR, immediate release; S, standard; SR, sustained release; XL, extended release. Reprinted with permission from Urology, Volume 64, Djavan B et al, State of the art on the efficacy and tolerability of alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonists in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia, pp. 1081–1088, Copyright Elsevier 2004.38

The AUA guidelines update from 2003 also suggests that the safety profile for the 4 available alpha blockers is reasonable and similar, with a few notable exceptions. Titratable long-acting alpha1 blockers terazosin and doxazosin are more prone to hypotensive and cardiovascular events, whereas tamsulosin has a unique tendency to induce an ejaculation, presumably due to blockage of the 5-hydroxytriptamine receptor. A study by Hellstrom and Sikka believed this phenomenon to be a retrograde ejaculation induced by a relaxation of the bladder neck.13

The rapid decline of the use of TURP and other surgical procedures for BPH in the 1990s is due in part to the introduction of medical therapy; however, it is questionable to what degree alpha-adrenergic receptor blockade contributed to this decline. This caution is justified by several observations. Alpha blockers do not seem to interfere with the natural history of benign prostatic growth. A detailed analysis of the per-protocol population in the MTOPS study showed that patients treated with doxazosin .4 or .8 mg over 4 to 5 years experienced a prostate volume increase of 18% on average, identical to the growth rate seen in the placebo group.1 Although it had been suggested that the quinazolin derivatives, such as terazosin and doxazosin, and, perhaps, even other alpha blockers, might have an impact upon prostate growth by inducing apoptosis,14 it does not appear that this is clinically relevant. Noting that the prostate continues to grow despite treatment with an alpha blocker, it seems logical that those events that are triggered by prostate size and its increase over time would occur at a rate similar to that observed in nontreated or placebo-treated patients. This consideration is justified by the observation made by Mochtar and colleagues, who found that patients with a PSA level of less than 1.5 ng/mL treated with alpha blockers had a 5-year cumulative risk of re-treatment of 20% versus those with a PSA of greater than 3 ng/mL, who had a 5-year cumulative risk of re-treatment of 45%. A similar differentiation was made regarding prostate sizes of less or greater than 30 mL, which again showed a higher re-treatment rate in larger prostates.15 Clinical observations suggest that the reduction in the rate of AUR and surgery is more likely due to 5ARI use compared to the use of alpha blockers. In 2 large datasets,16,17 the risk of retention and/or surgery was significantly greater over time in patients on alpha blockers compared to those on 5ARIs.

5ARIs. A completely different approach to the medical therapy of men with LUTS and clinical BPH is represented by the use of 5ARIs. The background to this form of therapy comes from an observation made by Wilson and Imperato-McGinley, who reported independently but nearly simultaneously on kindreds of families affected by a deficiency in the enzyme 5-alpha reductase, which is responsible for the reduction of testosterone to dihydrotesterone (DHT).18,19

Individuals affected by the congenital deficiency suffer from an inhibited conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone by the absence of 5-alpha-reductase isoenzyme type 2. DHT is a stronger contributor to prostate growth compared to testosterone, and, thus, this particular situation is believed to be the cause for the observation that affected individuals do not develop either BPH or prostate cancer in later life. Based on the theory that mimicking this metabolic defect would result in a drug effective for the treatment of BPH, inhibitors of the steroid 5-alpha-reductase isoenzyme type 2 were developed, and the first such inhibitor, finasteride, was released for use in the early 1990s.20

Since then, it has been demonstrated that there are 2 isoenzymes of 5ARIs.21 Finasteride inhibits only type 2, and the newer 5ARI, dutasteride, inhibits both isoenzymes and leads to a greater decrease in serum DHT level. Both compounds decrease intraprostatic DHT by 80% to over 90%, respectively. This reduction in DHT inside the prostate leads to atrophic changes, and these atrophic changes lead to a decrease in prostate volume by an average of 15% to 25% over time. Finasteride leads to an improvement in the IPSS of 3 to 4 points in both randomized, placebo-controlled and open-label extension studies, and a sustained improvement in peak urinary flow rate of approximately 2 mL/s, according to the AUA guidelines (Table 1). By inducing a volume reduction and improving symptoms as well as urinary flow rate, 5ARIs eventually reduce the risk of acute urinary retention as well as BPH-related surgery by a margin of greater than 50% (Table 3).22,23

Table 3.

Comparison of Efficacy of 5-Alpha-Reductase Inhibitors From Representative Studies of Finasteride and Dutasteride*

| Finasteride | Dutasteride | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48-Month Controlled | 24-Month Controlled | |||

| Trial in 3040 Men |

Trial in 4325 Men |

|||

| Symptom | Finasteride | Placebo | Dutasteride | Placebo |

| Volume changes | −18% | +14% | −26% | −2% |

| IPSS reduction | −3.3 | −1.3 | −4.5 | −2.3 |

| Qmax improvement | +1.9 | +0.2 | +2.2 | +0.6 |

| AUR risk reduction | 57% | 57% | ||

| Surgery risk reduction | 55% | 48% | ||

In direct comparison, it appears that 5ARIs in general provide slightly less symptomatic improvement compared to alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers. They do, however, interfere with the natural history of the disease, and by this mechanism provide the long-term benefit of risk reduction for progression to acute urinary retention and surgery. The most recent study (Combination of Avodart® and Tamsulosin; CombAT) comparing dutasteride with tamsulosin suggests that in patients particularly susceptible to treatment with 5ARIs by having larger glands and higher serum PSA values, dutasteride provides symptomatic relief superior to tamsulosin after 1 year.24

Combinations of Different Medication Classes

Alpha blockers and 5ARIs. The recognition that alpha blockers provide early symptomatic relief, whereas 5ARIs provide long-term disease management led to the idea of combining both drugs in the medical management of men with LUTS and clinical BPH. Two 1-year randomized, placebo-controlled studies failed to show a significant benefit of combination therapy over monotherapy with the alpha blocker alone.25,26

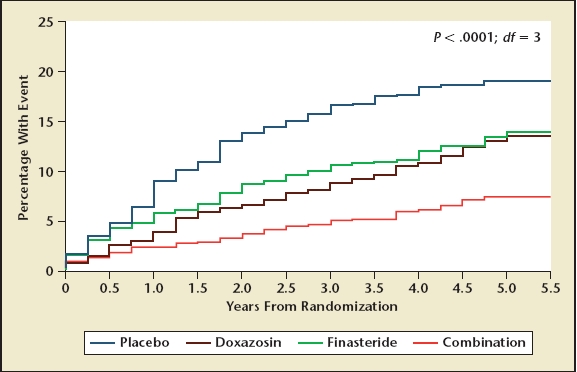

A landmark trial studying men with LUTS and BPH, however, changed this perception. In 2003, results from the MTOPS trial were published. MTOPS enrolled 3057 men with LUTS and clinical BPH and randomized them to treatment with placebo, doxazosin, finasteride, or a combination of doxazosin and finasteride over a period of 4 to 5 years. Designed as a progression trial, its primary endpoint was the combined outcome of progression by symptomatic worsening, retention of urine, urinary tract infection, deterioration of renal function, or socially acceptable incontinence. Combination therapy proved superior to both single-arm therapies in terms of the primary outcome (Figure 5). Progression to surgery triggered by BPH and symptoms was a secondary endpoint, as were outcomes such as changes in symptom score and peak urinary flow rate.1 In terms of symptom score, the treatments provided improvements of 4.9, 5.6, 6.6, and 7.4 points in the placebo, finasteride, doxazosin, and combination therapy group, respectively. Similarly, urinary flow rate improvements were 2.8, 3.2, 4.0, and 5.1 mL/s for the 4 treatment groups, respectively. The MTOPS trial convincingly demonstrated that long-term disease management by combination medical therapy can be effective and results in superior outcomes, particularly in patients who at baseline are at increased risk for progression (those with enlarged prostates and higher serum PSA levels). In fact, the baseline risks for symptomatic worsening, urinary retention, and invasive therapy for BPH increases with increasing prostate size and serum PSA, as does the overall risk reduction with combination medical therapy. These observations suggest that combination therapy should be the medical therapy of choice for those men who have the highest baseline risk for progression, that is, patients with prostates larger than 30 to 40 g and PSA values of greater than 1.5 ng/mL at baseline. A common criticism of the MTOPS study and its implications has been that combination therapy is quite costly, adding the cost of 2 medications to achieve the desired benefit. The combination therapy group also suffers the combined adverse events associated with both an alpha blocker and finasteride (Table 4).

Figure 5.

Cumulative incidence of progression in the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) study. Reprinted with permission from McConnell J et al.1 Copyright © 2003 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Table 4.

Ten Most Frequent Adverse Events Observed in the Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms (MTOPS) Study

| Rate per 100 Person-Years at Risk |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side Effect | Placebo | Doxazosin | Finasteride | Combination |

| Erectile dysfunction | 3.6 | 3.9 | 4.9* | 5.6* |

| Dizziness | 2.5 | 4.8* | 2.5 | 5.9* |

| Postural hypotension | 2.5 | 4.4* | 2.7 | 4.6* |

| Asthenia | 2.2 | 4.5* | 1.7 | 4.6* |

| Decreased libido | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.5* | 2.8* |

| Abnormal ejaculation | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.9* | 3.4* |

| Peripheral edema | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.4* |

| Dyspnea | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.3* |

| Somnolence | 0.4 | 0.9* | 0.4 | 0.9* |

| Syncope | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.7* |

Higher compared to placebo at P < .05.

Data from McConnell J.36

Alpha blockers and antimuscarinic agents. Men with LUTS have voiding symptoms, such as hesitancy, intermittency, slow stream, and incomplete emptying, and storage symptoms, such as urgency, frequency, nocturia, and urge urinary incontinence. In fact, it has been argued that storage symptoms are more bothersome to the patient and drive more patients to seek health care compared to voiding symptoms.27,28 These symptoms in women are called OAB and have been underrecognized and undertreated in men. Recently, several reports entered the peer-reviewed literature that demonstrated the efficacy and safety of adding antimuscarinic agents, such as tolterodine and oxybutynin, to an existing regimen with an alpha blocker, particularly in patients suffering from OAB symptoms.29,30

In addition to trials adding the antimuscarinic agents to an already existing (and partially failing) regimen of alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers, the Tolterodine and Tamsulosin in Men With LUTS Including OAB: Evaluation of Efficacy and Safety (TIMES) study entered nearly 900 patients into a 12-week, randomized, placebocontrolled trial and assigned patients to placebo versus tamsulosin (.4 mg) versus extended-release tolterodine (4 mg) versus a combination of tolterodine and tamsulosin.2

Patients eligible for this study had to have typical voiding and typical storage or OAB-type symptoms and were a symptomatic group of men. The primary endpoint consisted of the patient’s perception of benefit in terms of the bladder condition and was only significant against placebo in the combination therapy group. In fact, of all the primary and secondary outcomes, the combination therapy group achieved clinical significance in all, whereas tolterodine and tamsulosin achieved significance against placebo in only 1 of the secondary outcomes. The conclusion from the TIMES study was that patients bothered by LUTS, including diary-documented OAB, do not respond to monotherapy with either alpha blockers or antimuscarinic agents, but have a statistically and clinically significant treatment benefit from combination therapy of an alpha blocker and an antimuscarinic agent. The treatment was associated with the typical adverse event profile observed with both alpha blockers and antimuscarinic agents, but a low incidence of acute urinary retention was observed in all treatment groups.

Alpha blockers and PDE-5 inhibitors. Recently, several phase II and proof-of-concept trials were published that demonstrated a substantial and beneficial effect of PDE-5 inhibitors commonly used for the treatment of erectile dysfunction and the treatment of men with LUTS.31,32 Recognizing the potential for an additive effect, Kaplan and colleagues treated 62 patients with LUTS and sexual dysfunction with a combination of the alpha-adrenergic receptor blocker alfuzosin 10 mg once daily, or sildenafil 25 mg once daily, or a combination of both for 12 weeks.33 The patients in the combination group experienced a greater improvement in IPSS, peak urinary flow rate, and even erectile dysfunction scores, suggesting that even this combination may have promise and benefit to a subgroup of patients suffering from both LUTS and erectile dysfunction, albeit at the additional expense of 2 medications and the associated side-effect spectrum.

Efficacy Versus Patient Expectation

From the above discussion, it is quite clear that there is a ceiling for the efficacy of medical therapy in terms of symptom improvement. The standard medications, such as alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers and 5ARIs, as well as various combinations, such as alpha blockers plus 5ARIs, alpha blockers plus antimuscarinic agents, and alpha blockers plus PDE-5 inhibitors, achieve an improvement in IPSS somewhere between 3 and 7 points (Table 1). Even using selective drugs or a combination of drugs for specific patients at lesser or greater risk, with larger or smaller prostates, higher or lower PSA, or more voiding or more storage symptoms, the fundamental observation is that no medical therapy has ever achieved an improvement in the symptom score approaching 10 points from baseline. In addition, part of the symptomatic improvement is due to a placebo effect, as evidenced by the strong placebo response in virtually all placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trials.

Several studies have attempted to correlate patients’ expectations and interpretations of improvement in the symptom score by matching global objective assessment against the actual observed changes in the IPSS.34,35

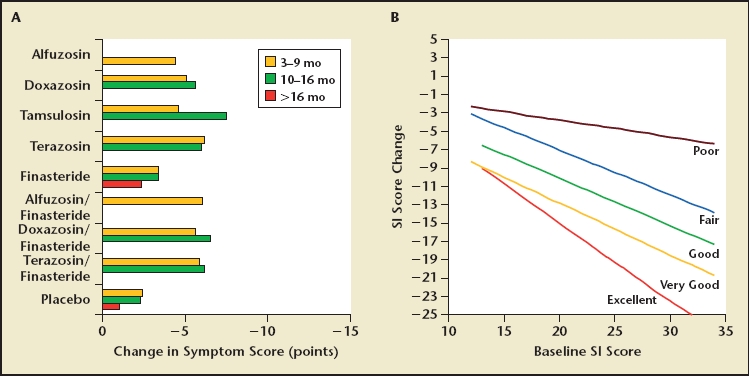

Figure 6 demonstrates the relationship between baseline IPSS and changes in IPSS versus self-rating the relief of symptoms in a 12-month study with terazosin versus placebo. Patients who improved by 1 to 2 points interpreted their changes as relatively poor, independent of their baseline score. Patients who improved from 7 to 25 points perceived the change as excellent; patients who improved 1 to 13 points perceived the change as fair; patients who improved 3 to 16 points perceived the change as good; and patients who improved from 7 to 19 points perceived the change as very good. The higher the baseline score, that is, the more symptomatic a patient, the greater the drop from baseline it takes for the patient to perceive the same degree of improvement. For example, a patient would interpret a drop of 5 points as a good improvement if he started with a severity score of 15, but if he started with a severity score of 25, a drop of 10 points would be required to achieve the same interpretation of a good improvement.

Figure 6.

Symptom score improvement observed with medical therapy based on American Urological Association benign prostatic hyperplasia guidelines6; range of improvement from 3 to 7 points (A). (B) Relationship between baseline symptom score and improvement in score after therapy. The lines indicate the average reduction in score required for patients to experience poor, fair, good, and very good improvement in their symptoms by global assessment.35 The graph suggests that all forms of medical therapy achieve a fair rating often, a good rating infrequently, and a very good rating rarely, based on the average improvement shown in (A).

When matching this graph with the prior observation of the efficacy of medical therapy (Figure 6A), it seems clear that medical therapy falls short of achieving more than a fair-to-good improvement in most cases. The ceiling of less than 10 points improvement very rarely leads to the perception of a very good or excellent improvement, which is reserved for surgical interventions.

Medication Compliance in Large Trials

Although medical therapy is the most widely used form of management for men with LUTS and OAB, treatment efficacy rarely leads to a level of improvement the patients would rate as excellent or very good. In addition, long-term medical management incurs certain adverse events typical for the class of medications used. The most effective medical management, that is, management with combination therapy, has the combined adverse event profile of both classes of medication. It is not surprising that in a situation where efficacy is less than ideal and side effects are not uncommon, compliance with medical therapy is not anywhere close to 100%. Although patients in shorter-term medication trials tend to stay on medication despite experiencing adverse events, in long-term treatment trials patients choose to discontinue treatment rather than suffer from side effects for a period of 6 months, 1 year, or even 2 to 5 years, as is the case in the ALTESS, Proscar Long-term Efficacy and Safety Study (PLESS), dutasteride phase III, and MTOPS studies. Table 5 provides a summary of compliance and dropout rates in selected medical management trials for men with LUTS and OAB, suggesting the relatively high proportion of patients unwilling to tolerate the side effects associated with the benefit experienced from the treatment.

Table 5.

Dropout Rates in Selected Medical Therapy Trials Ranging From 12 Weeks to 5 Years

| Placebo |

Drug |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discontinued | Discontinued | |||||

| Due to Adverse | Due to Adverse | |||||

| Study | n | Discontinued | Effects | n | Discontinued | Effects |

| TIMES, 12 weeks37 | 222 | 32/14/4% | 7/3.2% | Tolterodine, 217 | 27/12.4% | 5/2.3% |

| Placebo vs tolterodine vs | Tamsulosin, 215 | 29/13.5% | 7/3.3% | |||

| tamsulosin vs combination | Combination, 225 | 34/15.1% | 20/8.9% | |||

| PREDICT, 12 months26 | 270 | 76/28.1% | 30/11.1% | Doxazosin, 275 | 78/28.4% | 32/11.6% |

| Placebo vs doxazosin vs | Finasteride, 264 | 81/30.7% | 34/12.9% | |||

| finasteride vs combination | Combination, 286 | 89/31.1% | 30/10.5 | |||

| Veterans Administration | 305 | 51/16.7% | 5/1.6% | Terazosin, 305 | 49/16.1% | 18/5.9% |

| COOP, 12 months25 | Finasteride, 310 | 67/21.6% | 15/4.8% | |||

| Placebo vs terazosin vs | Combination, 309 | 55/17.8% | 24/7.8% | |||

| finasteride vs combination | ||||||

| CombAT study, 2 years, | Tamsulosin, 1611 | 357/22% | 136/8.4% | |||

| Interim24 | Dutasteride, 1623 | 322/20.0% | 108/6.7% | |||

| Tamsulosin vs dutasteride | Combination, 1610 | 343/21.0% | 154/9.6% | |||

| vs combination | ||||||

| PLESS, 4 years22 | 1524 | 524/34.4% | 176/11.5% | 1516 | 633/41.8% | 166/10.9% |

| Placebo vs finasteride | ||||||

| MTOPS, 4–5 years1 | 737 | Doxazosin, 756 | 27%* | |||

| Placebo vs finasteride vs | Finasteride, 768 | 24% | ||||

| doxazosin vs combination | Combination, 786 | 18% | ||||

Most discontinuation due to adverse effects, according to the primary manuscript.

The Future of Medical Therapy for Men With LUTS and BPH

This review does not suggest that medical therapy does not play an extremely useful role in the management of men with LUTS and/or OAB and BPH. In fact, the majority of patients are managed successfully with medical therapy, particularly if their health care provider discerns whether they would be most suitable for treatment with an alpha blocker, 5ARI, an antimuscarinic agent, or a combination of medications.

However, this review clearly illustrates that there is a ceiling of efficacy in medical therapy and a very real effect in terms of adverse events. Patients dissatisfied with the efficacy and/or displeased with side effects can choose to proceed to minimally invasive surgical treatment, such as transurethral microwave thermotherapy or transurethral needle ablation; to surgical treatment, such as a transurethral resection or incision of the prostate; or to laser ablation.

A welcome addition to our armamentarium is a nonsurgical and noninvasive intervention that provides rapid symptom relief with long-term disease management while being devoid of serious side effects that lead to problems with patient compliance. Such a medication, given in the form of an injectable or an implantable depot preparation lasting for several months or up to 1 year—thereby increasing compliance—would find a welcome niche in the marketplace of management alternatives for men with LUTS and/or OAB and clinical BPH.

Main Points.

The presence or absence of lower urinary tract symptoms is independent of the presence of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), benign prostatic enlargement, or bladder outlet obstruction.

Alpha-adrenergic receptor blockers are suitable for quick and effective symptom relief while not actually influencing the natural history of disease.

5-Alpha-reductase inhibitors have been proven ineffective in men with smaller prostates and lower prostate-specific antigen (PSA) values, but have reasonable symptom improvement efficacy in men with larger prostate glands and higher PSAs. They also interfere with the natural history of disease by preventing further prostate growth and reducing the risk of acute urinary retention and the subsequent need for surgery.

Several reports demonstrate the efficacy and safety of adding antimuscarinic agents such as tolterodine and oxybutynin to an existing alpha-blocker regimen, particularly in patients suffering from overactive bladder symptoms.

Medical therapy falls short of achieving a patient perception of more than fair-to-good improvement in most cases. The perception of very good or excellent improvement is reserved for surgical interventions for LUTS and BPH.

Patients dissatisfied with the efficacy and/or displeased with adverse side effects can choose to proceed to minimally invasive surgical treatment, such as transurethral microwave thermotherapy, transurethral needle ablation, or to surgical treatment, such as transurethral resection or incision of the prostate or laser ablation.

References

- 1.McConnell J, Roehrborn C, Bautista O, et al. The long-term effects of doxazosin, finasteride and the combination on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2385–2396. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Rovner ES, et al. Tolterodine and tamsulosin for treatment of men with lower urinary tract symptoms and overactive bladder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2319–2328. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.19.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.He W, Sengupta M, Velkoff VA, DeBarros KA. 65+ in the United States: 2005. Washington, DC: National Institute on Aging and US Census Bureau; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McConnell JD, Barry MJ, Bruskewitz RC, et al. Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Diagnosis and Treatment. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994. (Clinical Practice Guideline, No. 8). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobsen SJ, Girman CJ, Guess HA, et al. New diagnostic and treatment guidelines for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Potential impact in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:477–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AUA Practice Guidelines Committee, authors. AUA guideline on management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (2003). Chapter 1: diagnosis and treatment recommendations. J Urol. 2003;170:530–547. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000078083.38675.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caine M. The present role of alpha-adrenergic blockers in the treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy. J Urol. 1986;136:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)44709-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lepor H, Gup DI, Baumann M, et al. Laboratory assessment of terazosin and alpha-1 blockade in prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 1988;32:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lepor H, Knapp-Maloney G, Wozniak-Petrofsky J. The safety and efficacy of terazosin for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1989;27:392–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roehrborn CG, Prajsner A, Kirby R, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study evaluating the onset of action of doxazosin gastrointestinal therapeutic system in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2005;48:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roehrborn CG, Schwinn DA. Alpha1-adrenergic receptors and their inhibitors in lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2004;171:1029–1035. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000097026.43866.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roehrborn CG. Alfuzosin 10 mg once daily prevents overall clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia but not acute urinary retention: results of a 2-year placebo-controlled study. BJU Int. 2006;97:734–741. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellstrom WJ, Sikka SC. Effects of acute treatment with tamsulosin versus alfuzosin on ejaculatory function in normal volunteers. J Urol. 2006;176:1529–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyprianou N. Doxazosin and terazosin suppress prostate growth by inducing apoptosis: clinical significance. J Urol. 2003;169:1520–1525. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000033280.29453.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mochtar CA, Kiemeney LA, Laguna MP, et al. Prognostic role of prostate-specific antigen and prostate volume for the risk of invasive therapy in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia initially managed with alpha1-blockers and watchful waiting. Urology. 2005;65:300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boyle P, Roehrborn C, Harkaway R, et al. 5-Alpha reductase inhibition provides superior benefits to alpha blockade by preventing AUR and BPH-related surgery. Eur Urol. 2004;45:620–626. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Souverein PC, Erkens JA, de la Rosette JJ, et al. Drug treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia and hospital admission for BPH-related surgery. Eur Urol. 2003;43:528–534. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imperato-McGinley J, Guerrero L, Gautier T, et al. Steroid 5 alpha reductase deficiency in man: an inherited form of male pseudohermaphroditism. Science. 1974;186:1213–1215. doi: 10.1126/science.186.4170.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh PC, Madden JD, Harrod MJ, et al. Familial incomplete male pseudohermaphroditism, type 2. Decreased dihydrotestosterone formation in pseudovaginal perineoscrotal hypospadias. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:944–949. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197410312911806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gormley GJ, Stoner E, Bruskewitz RC, et al. The Finasteride Study Group, authors. The effect of finasteride in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1185–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210223271701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thigpen AE, Davis DL, Milatovich A, et al. Molecular genetics of steroid 5 alpha-reductase 2 deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:799–809. doi: 10.1172/JCI115954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McConnell JD, Bruskewitz R, Walsh P, et al. Finasteride Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study Group, authors. The effect of finasteride on the risk of acute urinary retention and the need for surgical treatment among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:557–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802263380901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roehrborn CG, Boyle P, Nickel JC, et al. Efficacy and safety of a dual inhibitor of 5-alpha-reductase types 1 and 2 (dutasteride) in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2002;60:434–441. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01905-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roehrborn CG, Siami P, Barkin J, et al. The effects of dutasteride, tamsulosin and combination therapy on lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic enlargement: 2-year results from the CombAT study. J Urol. 2008;179:616–621. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lepor H, Williford WO, Barry MJ, et al. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Study Group, authors. The efficacy of terazosin, finasteride, or both in benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:533–539. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirby RS, Roehrborn C, Boyle P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of doxazosin and finasteride, alone or in combination, in treatment of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: the Prospective European Doxazosin and Combination Therapy (PREDICT) trial. Urology. 2003;61:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irwin DE, Milsom I, Kopp Z, et al. Impact of overactive bladder symptoms on employment, social interactions and emotional well-being in six European countries. BJU Int. 2006;97:96–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chapple CR, Roehrborn CG. A shifted paradigm for the further understanding, evaluation, and treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in men: focus on the bladder. Eur Urol. 2006;49:651–659. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JY, Kim HW, Lee SJ, et al. Comparison of doxazosin with or without tolterodine in men with symptomatic bladder outlet obstruction and an overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2004;94:817–820. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Athanasopoulos AA, Perimenis PS. Comparison of doxazosin with or without tolterodine in men with symptomatic bladder outlet obstruction and an overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2005;95:1117–1118. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.5547_3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McVary KT, Roehrborn CG, Kaminetsky JC, et al. Tadalafil relieves lower urinary tract symptoms secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2007;177:1401–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McVary KT, Monnig W, Camps JL, Jr, et al. Sildenafil citrate improves erectile function and urinary symptoms in men with erectile dysfunction and lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a randomized, double-blind trial. J Urol. 2007;177:1071–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan SA, Gonzalez RR, Te AE. Combination of alfuzosin and sildenafil is superior to monotherapy in treating lower urinary tract symptoms and erectile dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2007;51:1717–1723. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barry MJ, Williford WO, Chang Y, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia specific health status measures in clinical research: how much change in the American Urological Association symptom index and the benign prostatic hyperplasia impact index is perceptible to patients? J Urol. 1995;154:1770–1774. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)66780-6. [see comments] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roehrborn CG, Oesterling JE, Auerbach S, et al. HYCAT Investigator Group, authors. The Hytrin Community Assessment Trial study: a one-year study of terazosin versus placebo in the treatment of men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 1996;47:159–168. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80409-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McConnell J. The long term effects of medical therapy on the progression of BPH: results from the MTOPS trial. J Urol. 2002;167 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Dmochowski R, et al. Tolterodine extended release improves overactive bladder symptoms in men with overactive bladder and nocturia. Urology. 2006;68:328–332. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Djavan B, Chapple C, Milani S, et al. State of the art on the efficacy and tolerability of alpha1-adrenoceptor antagonists in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2004;64:1081–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]