Abstract

Neonatal hypoxic/ischemic (H/I) brain injury causes neurological impairment, including cognitive and motor dysfunction as well as seizures. However, the molecular mechanisms regulating neuron death after H/I injury are poorly defined and remain controversial. Here we show that Atg7, a gene essential for autophagy induction, is a critical mediator of H/I-induced neuron death. Neonatal mice subjected to H/I injury show dramatically increased autophagosome formation and extensive hippocampal neuron death that is regulated by both caspase-3-dependent and -independent execution. Mice deficient in Atg7 show nearly complete protection from both H/I-induced caspase-3 activation and neuron death indicating that Atg7 is critically positioned upstream of multiple neuronal death executioner pathways. Adult H/I brain injury also produces a significant increase in autophagy, but unlike neonatal H/I, neuron death is almost exclusively caspase-3-independent. These data suggest that autophagy plays an essential role in triggering neuronal death execution after H/I injury and Atg7 represents an attractive therapeutic target for minimizing the neurological deficits associated with H/I brain injury.

Neonatal hypoxic/ischemic (H/I) brain injury causes neurological impairment, including cognitive and motor dysfunction as well as seizures.1,2 The patterns of neuron death after H/I injury in rodent models appear similar to those involved in human cases of H/I encephalopathy.3,4,5,6 Morphological and biochemical approaches have shown the presence of apoptotic and necrotic neuron death in the pyramidal layer of the hippocampus after H/I injury,7 whereas the extent of damage from H/I injury depends on the degree of brain maturation and the severity of the insult.8,9,10 Apoptotic neuron death after H/I injury is accompanied by the activation of caspases, which may be associated with proapoptotic factors such as Bax11,12 or Bad,13 and suppressed by anti-apoptotic factors such as Bcl-xL.14 Although many neuroprotective strategies have been proposed, few anti-apoptotic therapies have proven to be useful in inhibiting H/I-induced brain injury.15 Therefore, it is very important to understand what molecular pathways are executed in neuron death induced by H/I brain injury.

Autophagy, which is a highly regulated process involving the bulk degradation of cytoplasmic macromolecules and organelles in mammalian cells via the lysosomal system, is induced under starvation, differentiation, and normal growth control to maintain cellular homeostasis and survival.16,17,18 Simultaneously, it has also been evident that autophagy participates in various neurodegenerative disorders19,20,21,22 and further that it can trigger a form of cell death distinct from apoptosis in neurons.23,24,25,26 In particular, we have previously shown that autophagy is highly induced in CA1 pyramidal neurons of gerbil hippocampus after brief forebrain ischemia, whereas such neurons that contain numerous autophagosomes/autolysosomes in the perikarya undergo delayed neuronal death.27 The induction of autophagy has been shown in neonatal and adult mouse cortex and striatum after H/I injury,10,28 and LC3, a marker protein for autophagy, is required for autophagosome formation via its conversion from LC3-I to LC3-II.29 However, it is unclear if autophagy participates as a pro- or anti-death factor in the execution of neuron death after H/I injury.30

Here, to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of pyramidal neuron death in the hippocampus after H/I injury, we used an ischemia model of left carotid artery occlusion followed by exposure to low oxygen31 and found that H/I injury-induced pyramidal neuron death in the neonatal hippocampus occurred using both caspase-dependent and -independent pathways. In such damaged neurons autophagy was strongly induced, and this ischemic neuronal death was rescued by an Atg7 deficiency. These data indicate that autophagy plays an essential role in the execution of pyramidal neuron death in the neonatal mouse hippocampus after H/I injury.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The experiments described below were performed in compliance with the regulations of Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine’s Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Neonatal and adult C57BL/6J mice at postnatal day 7 (P7) and 8 weeks of age were obtained from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan) or Charles River Laboratories Japan (Yokohama, Japan). Nestin-Cre transgenic mice [strain name: B6.Cg(SJL)-Tg(nestin-Cre)1Kln/J]32 were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Atg7flox/flox mice,16 CAD homozygous (−/−) mice,33 and caspase-3 heterozygous (+/−) mice backcrossed onto a C57BL/6 background for at least 10 generations34,35 were transferred to the Institute of Experimental Animal Sciences, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, and were housed in a pathogen-free facility. Atg7flox/flox mice were bred with nestin-Cre transgenic mice to produce Atg7flox/flox; nestin-Cre mice.36 Caspase-3+/− mice were crossed to obtain a mixture of +/+, +/−, and −/− pups. To determine the genotypes of these lines, genomic DNA was prepared from pup tail snips and analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The following primer sets were used for genotyping: for the Cre transgene, 5′-TTTGCCTGCATTACCGGTCGATGCAAC-3′ and 5′-TGCCCCTGTTTCACTATCCAGGTTACGGA-3′; wild-type and Atg7flox alleles, 5′-TGGCTGCTACTTCTGCAATGATGT-3′ and 5′-CAGGACAGAGACCATCAGCTCCAC-3′16; wild-type and mutant CAD alleles, 5′-AAAAGAACAGTCGGGACTGC-3′, 5′-GATTCGCCAGCGCATCGCCTT-3,′ and 5′-TTCACACCAGGAGACATCTG-3′33; wild-type and mutant caspase-3 alleles, 5′-AGGGTCCCATTTGCATAGCTTTGC-3′, 5′-GCGAGTGAGAATGTGCATAAATTC-3,′ and 5′-TGCTAAAGCGCATGCTCCAGACTG-3′.34

Hypoxic-Ischemic Injury

Neonatal and adult H/I brain injury was induced in mice on P7 and at 8 weeks of age, respectively, essentially according to the Rice-Vannucci model,31 with minor modifications.10 After the mice were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane (2%), the left common carotid artery was dissected and ligated with silk sutures (6/0). After the surgical procedure, the pups and adult mice were allowed to recover for 1 hour. They were then placed in chambers maintained at 37°C through which 8% humidified oxygen (balance, nitrogen) flowed for 40 or 45 minutes (neonate) or 35 or 40 minutes (adult). After hypoxic exposure, the pups and adult mice were returned to their dams and the plastic cages, respectively. The animals were allowed to recover for 3, 8, 24, or 72 hours, or 7 days (neonate). At each stage, brains were processed for biochemical and morphological analyses. This procedure resulted in brain injury in the ipsilateral hemisphere, consisting of cerebral infarction mainly in the hippocampus.9,13 Control littermates were neither operated on nor subjected to hypoxia.

Antisera

The preparation of rabbit antibodies against rat LC321,37 and Atg738 was described previously. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against ubiquitin (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), caspase-3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175; Cell Signaling), and cleaved caspase-7 (Asp198; Cell Signaling), and mouse monoclonal antibodies against glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (clone 6C5; Ambion, Austin, TX), caspase-7 (clone 10-1-62; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), and neuronal nuclei (NeuN) (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) were obtained commercially.

Sample Preparation for Histochemical and Morphological Analyses

After H/I injury (n = 3 to 5 for each procedure and each stage), mice were deeply anesthetized with pentobarbital (25 mg/kg i.p.) and fixed by cardiac perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde buffered with 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 4% sucrose for light microscopy and with 2% paraformaldehyde-2% glutaraldehyde buffered with 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer for ordinary electron microscopy.21,39,40 For light microscopy, brain tissues were quickly removed from the mice and further immersed in the same fixative for 2 hours at 4°C. Samples processed for paraffin embedding were cut into 5-μm sections with a semimotorized rotary microtome (RM2245; Leica, Nussloch, Germany) and placed on silane-coated glass slides. Samples for cryosections were embedded in OCT compound (Miles, Elkhart, IN) after cryoprotection with 15% and 30% sucrose solutions and cut into 10-μm sections with a cryostat (CM3050,; Leica). The sections were placed on silane-coated glass slides and stored at −80°C until used. For routine histological studies, paraffin sections or cryosections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Samples for electron microscopy were postfixed with 2% OsO4 with 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer, block-stained in 1% uranyl acetate, dehydrated with a graded series of alcohol, and embedded in Epon 812 (TAAB, Reading, UK). For light microscopic observations, semithin sections were cut at 1 μm with an ultramicrotome (Ultracut N; Reichert-Nissei, Tokyo, Japan) and stained with toluidine blue. For electron microscopy, silver sections were cut with an ultramicrotome, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and observed with an electron microscope (H-7100; Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunohistochemical Analyses

For double-immunofluorescent staining, cryosections were first incubated with anti-LC321,37 (1:100) or anti-cleaved caspases-3 or -7 (1:100) at 4°C overnight, followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG coupled with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) for 1 hour at room temperature. For LC3 detection, further incubations were performed with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and finally with streptavidin coupled with Alexa Fluor 488 for 1 hour at room temperature. After immunostaining, terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining was performed as described below. The sections were then viewed under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM 5 Pascal: Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany; or FV1000: Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). For NeuN staining, deparaffinized sections or cryosections were autoclaved for 20 minutes in 10 mmol/L Na-citrate buffer (pH 6.1)36 before the incubation with NeuN (1:1000). For ubiquitin staining, sections were incubated with anti-ubiquitin (1:1000) without pretreatment. These sections were further incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit or mouse IgG for 1 hour, and finally with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour at room temperature. Staining for peroxidase was performed using 0.0125% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and 0.002% H2O2 in 0.05 mol/L Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.6) for 10 minutes.

TUNEL Staining

TUNEL staining was applied to deparaffinized sections or cryosections as previously described.27,40,41 Briefly, sections with or without a 10-minute proteinase K (20 μg/ml) pretreatment at room temperature were incubated with 100 U/ml terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and 10 nmol/L biotinylated 16-2′-dUTP (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) in TdT buffer (100 mmol/L sodium cacodylate, pH 7.0, 1 mmol/L cobalt chloride, 50 μg/ml gelatin) in a humid atmosphere at 37°C for 1 hour, followed by further incubation with Alexa Fluor 594 or peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour at room temperature. Staining for peroxidase was performed as above. In the case of double-immunofluorescent staining, an in situ cell death detection kit, TMR red (Roche Diagnostics), was used according to the manufacturer’s recommended protocol after immunohistochemistry.

Cell Counting

The number of neurons with pyknotic nuclei in sections stained by H&E and that of neurons positive for TUNEL or cleaved caspase-3, or double-positive for TUNEL and cleaved caspase-3 in sections doubly stained for TUNEL and cleaved caspase-3, respectively, were counted in the whole pyramidal regions of the hippocampus located in the same portion (bregma: −1.82 mm of adult C57BL/ 6J mice42) by light microscopy (magnification, ×200) (three sections per animal). Data from three animals at each stage were averaged.

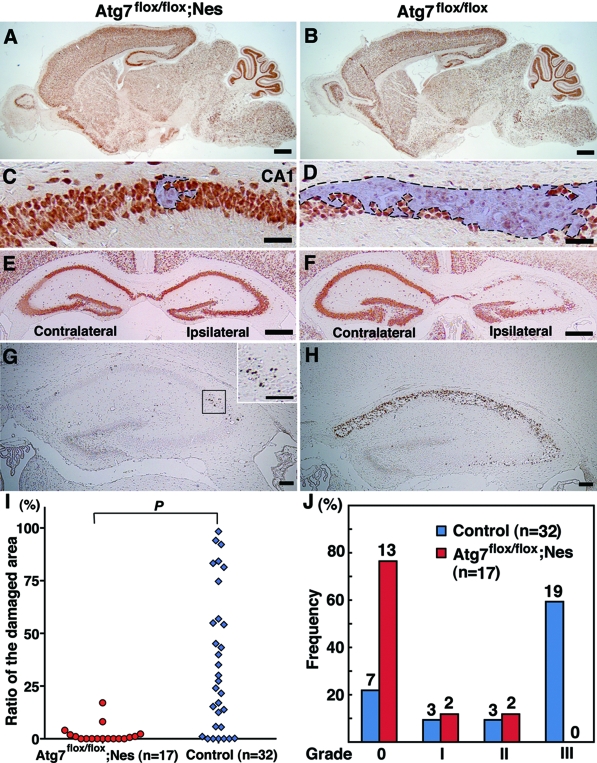

Neuropathological Evaluations

H/I injury and neuroprotection were evaluated by the damaged area and the number of TUNEL-positive (dead) neurons in the pyramidal layers of the hippocampus 3 days after H/I injury using brain sections corresponding to the same portion of the hippocampus as mentioned above. The total and damaged areas in the whole pyramidal layers of the ipsilateral hippocampus from each animal were measured using a morphological analysis software version 2.5 (Mac SCOPE; Mitani Corp., Fukui, Japan). The damaged area was defined as a region of the pyramidal layers that was NeuN-negative (see Figure 7D). The degree of H/I injury 3 days after ischemic insult was classified into four grades: the number of TUNEL-positive neurons in the pyramidal layers of the hippocampus per section was less than 10 for grade 0, 11 to 100 for grade I, 101 to 200 for grade II, and more than 201 for grade III. The percentage of mice showing each grade was further calculated in the cases of Atg7-deficient mice (n = 17) and their littermate controls (n = 32). The damaged area in the hippocampal pyramidal layers was also examined 7 days after H/I injury, in which time clear-cut shrinkage occurred in the ipsilateral hippocampus of control littermate mice (Atg7flo/flox mice), resulting in loss of ipsilateral hippocampal areas. To quantitate these damaged areas after neonatal HI, the areas of lesioned and unlesioned hippocampi were measured and compared within the same section, using the same software as mentioned above.13 The area loss of the lesioned ipsilateral hippocampus was calculated as a percentage of the intact contralateral hippocampus and the area loss was determined for each animal by measurement of at least three sections according to the method mentioned above. The degree of hippocampal damage was measured using Atg7-deficient (n = 11) and their littermate control (n = 12) mice.

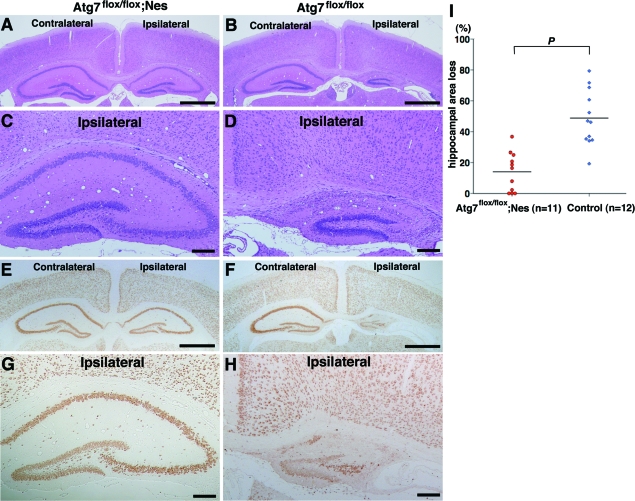

Figure 7.

Prevention of neuronal loss in the pyramidal layers of the hippocampus is further sustained in Atg7-deficient mice until 7 days after H/I injury. A–H: Frontal sections of Atg7-deficient (Atg7flox/flox; Nes) (A, C, E, G) and its control littermate (Atg7flox/flox) (B, D, F, H) mouse brains 7 days after H/I injury. H&E (A–D) and NeuN (E–H) staining. I: Evaluation of the area loss in the ipsilateral hippocampi of Atg7-deficient (n = 11) and littermate control (n = 12) mouse brains 7 days after H/I injury. The mean value of the area loss in the ipsilateral hippocampus was significantly lower in Atg7-deficient mice (14.0) than in their littermate control mice (48.8). P < 0.0001 (Mann-Whitney U-test) for the comparison of mean values between the two groups. Scale bars: 1000 μm (A, B, E, F); 200 μm (C, D, G, H).

Sample Preparations for Biochemical Analyses

Anesthetized mice were sacrificed by decapitation at 3, 8, 24, or 72 hours after H/I injury (n = 5 per group), and untreated control animals were sacrificed on P7 or at 8 weeks (n = 6 per group). The brains were rapidly dissected on a bed of ice. The left and right hippocampi were separately excised from the mice, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until used.

Analysis of DNA Fragmentation

Genomic DNA was isolated according to a previously described method.40 Briefly, each tissue was separately homogenized gently in 1 ml of a lysis buffer consisting of 4 mol/L guanidine thiocyanate and 0.1 mol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. Then, 20 μl of QIAEX II suspension (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was added to each sample, and the samples were vortexed, incubated at room temperature for 1 hour, and finally spun at 12,500 × g for 2 minutes. The pellets were washed by resuspending them three times in a NEW Wash solution (GENECLEAN kit; Bio 101, Vista, CA) consisting of 50% ethanol, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L Tris/HCl, and 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, pH 7.5, followed by resuspension in a TE buffer consisting of 10 mmol/L Tris/HCl and 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, pH 8.0. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes and spun at 12,500 × g for 2 minutes. The supernatants were collected and stored at −30°C until used.

To visualize DNA laddering in DNA samples from individual animals, a ligation-mediated polymerase chain reaction (LMPCR) was performed with some modifications, as outlined.43,44 Briefly, two unphosphorylated oligonucleotides (24 bp, 5′-AGCACTCTCGAGCCTCTCACCGCA-3′; 12 bp, 5′-TGCGGTGAGAGG-3′) were synthesized (Invitrogen). These are DNA fragments that are never amplified from normal mouse brain DNA. The oligonucleotides were annealed by heating to 55°C for 10 minutes, and the mixture was allowed to cool to 10°C for 55 minutes in advance of the experiment. Genomic DNA (1.0 μg) was mixed with 1 nmol each of the 24-bp and 12-bp unphosphorylated oligonucleotides in 50 μl of T4 DNA ligase buffer (Promega, Madison, WI) and 3 U of T4 DNA ligase (Promega). The mixture was incubated at 16°C overnight, and the samples were then diluted with TE to a final concentration of 5 ng/μl, and stored at −20°C until used for PCR. The 24-mer adaptor also served as a primer in the LMPCR (50 μl volume), in which 25 ng of ligated DNA was amplified with reagents from the Expand high-fidelity PCR system (Roche) under the following conditions: hot start (72°C for 8 minutes) with 1.75 U Expand high-fidelity enzyme mix (TaqDNA polymerase and Tgo DNA polymerase) added after 3 minutes, 20 (neonate) or 25 (adult) cycles (94°C for 1 minute, 72°C for 3 minutes), and postcycling (72°C for 15 minutes). The amplified DNA was separated by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel, visualized by staining with ethidium bromide, and photographed on a UV transilluminator (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Immunoblot Analysis

Each tissue was independently homogenized in a lysis buffer [1% Triton X-100 and 1% Nonidet P-40 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Nacalai, Kyoto, Japan). After two centrifugations at 10,500 × g for 10 minutes each at 4°C, the protein concentrations in the supernatants were determined using the BCA protein assay system (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and used for immunoblotting. The samples (15 μg for the detection of LC3 or GAPDH, 40 μg for Atg7, or for caspases-3 and -7) were then analyzed by 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore Co., Bedford, MA) was performed according to the method of Towbin and colleagues.45 The sheets were soaked in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to block nonspecific binding, and then incubated overnight with anti-LC3 (1:1000), anti-GAPDH (10 ng/ml), anti-Atg7 (1 μg/ml), anti-caspase-3 (1:1000), anti-caspase-7 (1:1000), or anti-cleaved caspase-7 (1:1000). The membranes were washed three times for 10 minutes in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 and then further incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (pig anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse IgG, DAKO) diluted 1:1000. After three 10-minute washes in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20, the membranes were treated with Immobilon Western chemiluminescent horseradish peroxidase substrate (Millipore Co.) for 2 minutes and then observed using an LAS-3000 mini system (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan). Immunoreactive bands were quantified using the Image Gauge software (Fuji Photo Film). Based on the optical density of the different bands in individual animals (n = 3 for each stage) LC3-II/LC3-I ratio was calculated. As a reference of caspase-7 activation, primary mouse hepatocytes that were isolated according to the method as described previously46 and treated with tumor necrosis factor-α (25 ng/ml) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and actinomycin D (0.2 μg/ml) (Sigma) for 6 hours were used, and their lysates were subjected to Western blotting.

Measurement of DEVDase (Caspases-3 and -7) Activity

The DEVD-AMC cleavage assay in hippocampal tissue was performed as described elsewhere.40,44 Briefly, each tissue was independently homogenized in 100 μl of lysis buffer containing 10 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.5, 42 mmol/L KCl, 5 mmol/L MgCl2, 1 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.5% CHAPS, 1 mmol/L phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, and a protease inhibitor cocktail, and spun at 10,500 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Tissue lysates (10 μl each) were incubated in an opaque 96-well plate with 190 μl of assay buffer (25 mmol/L Hepes, 1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 3 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 0.1% CHAPS, 10% sucrose, and a protease inhibitor cocktail) containing 30 μmol/L of the following substrate; N-acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-AMC (for caspases-3 and -7) (Peptide Institute, Inc., Minoo, Japan). The fluorescence intensity (excitation, 365 nm; emission, 465 nm) was monitored using a Spectramax microtiter plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale. CA). The accumulation of fluorescence was linear for at least 45 minutes. Protein concentrations in each lysate were determined by BCA protein assay, as described above. The experiments were repeated three times with samples from each hippocampus, and the data from three animals in each group were averaged.

Statistical Analysis

Ratios (%) of the damaged areas to the total areas in the ipsilateral hippocampal pyramidal layers in Atg7-deficient (n = 17) and littermate control (n = 32) mice 3 days after H/I injury and the area loss (%) of the lesioned ipsilateral hippocampus that was calculated as a percentage of the intact contralateral hippocampus in Atg7-deficient (n = 11) and their littermate control (n = 12) mice 7 days after H/I injury, respectively, were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Differences between two groups were assessed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. We assumed statistically significant differences at P < 0.05.

Results

Presence of Caspase-Dependent and -Independent Neuron Death in the Hippocampus after H/I Injury

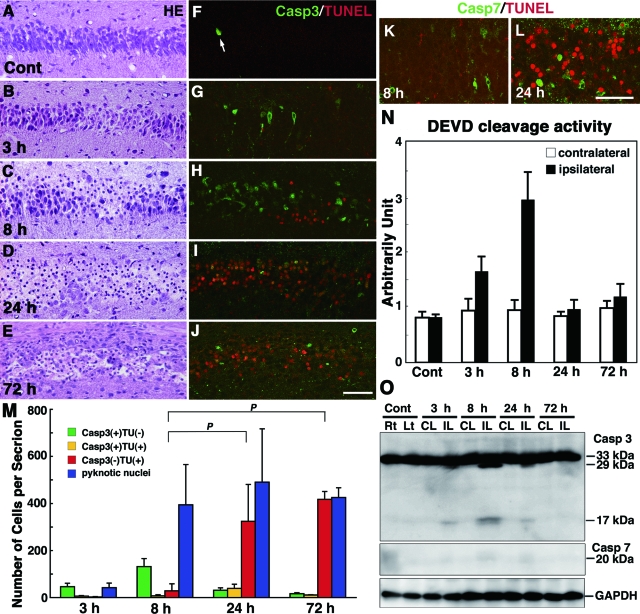

Because the hippocampus has been shown to be the most vulnerable to ischemic insult,9,13 we focused on the damage in the pyramidal regions of the hippocampus in neonatal and adult mouse brains after H/I injury and first re-examined the pathways that were involved in H/I injury-induced pyramidal neuron death in the neonatal hippocampus. In control neonatal mice at P7, hippocampal pyramidal neurons with pyknotic nuclei were hardly detected (Figure 1A), although positive staining for cleaved caspase-3 was demonstrated in a small number of pyramidal neurons with positive TUNEL staining in nuclei (Figure 1F). Such neuron death was naturally occurring cell death (programmed cell death) that has been shown in the hippocampus of mouse brains around P7.47 Damaged neurons after H/I injury were detected only in the ipsilateral hippocampus,9,13 whereas neurons in the contralateral hippocampus appeared histologically intact could not be distinguished from those in the untreated control brains (data not shown). In an H/I injury model using wild-type neonatal mice, we confirmed that the death mode of pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus was distinct from necrosis (Figure 1, B–D, G–J, and M); ∼35% of pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus were immunostained for activated caspase-3 8 hours after H/I injury (Figure 1, H and M). DEVDase activity was increased in the ipsilateral hippocampus 8 hours after H/I injury, whereas the cleaved form of caspase-3, but not caspase-7, was clearly detected in the tissue by Western blotting (Figure 1, N and O). By immunostaining, however, cleaved caspase-7-positive neurons appeared in the ipsilateral hippocampus after H/I injury, but they were rare (Figure 1, K and L; Figure 3C). The number of TUNEL-positive neurons increased at 24 and 72 hours, although the number of pyknotic neurons was already augmented 8 hours later (Figure 1M). These data indicate that both caspase-3-dependent and caspase-3-independent pyramidal neuron death occurred in the neonatal hippocampus after H/I injury.

Figure 1.

Activation of caspases and TUNEL staining in the hippocampus of wild-type neonatal mice after H/I injury. A–J: Histological sections of the left hippocampus of an untreated control (Cont) mouse at P7 (A, F) and ipsilateral hippocampus obtained 3 (B, G), 8 (C, H), 24 (D, I), and 72 hours (E, J) after H/I injury and stained with H&E (A–E) or for TUNEL and the active form of caspase-3 (F–J). An arrow in F shows a cleaved caspase-3-positive neuron undergoing programmed cell death. K and L: Double staining for TUNEL and the cleaved form of caspase-7 in the ipsilateral hippocampus at 8 (K) and 24 (L) hours after H/I injury. M: Number of neurons with pyknotic nuclei stained by H&E and the number of neurons positive for the active form of caspase-3 (Casp3), TUNEL (TU), or both in the pyramidal layers per hippocampal section at 3, 8, 24, and 72 hours after H/I injury. Counts were taken from three sections per animal, and the final value presented is the mean ± SD for three animals. P < 0.001. N: Proteolytic activity of the DEVDase for caspases-3 and -7 in the ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampi 3, 8, 24, and 72 hours after H/I injury. The activity in the nontreated hippocampus was used as a control. The final value presented is the mean ± SD for three animals. O: The cleavage of caspases-3 and -7 in the contralateral (CL) and ipsilateral (IL) hippocampi of wild-type neonatal mouse brains at 3, 8, 24, and 72 hours after H/I injury. Hippocampal tissues of the right (Rt) and left (Lt) sides from untreated neonatal mice were used as controls. Scale bars = 50 μm.

Figure 3.

H/I injury-induced pyramidal neuron death in the hippocampi of the wild-type and caspase-3-deficient neonatal mouse brains. A: Double staining of cleaved caspase-7 (Casp7) and DAPI in the contralateral hippocampus of a caspase-3-deficient mouse brain 8 hours after H/I injury. An arrow shows a cleaved caspase-7-positive neuron. B–E: Triple staining of cleaved caspase-3 (B, D) or cleaved caspase-7 (C, E), TUNEL, and DAPI in the ipsilateral hippocampi of wild-type (Wild) (B, C) and caspase-3-deficient (D, E) neonatal mouse brains 8 hours after H/I injury. F and G: The cleavage of caspase-7 (F) and GAPDH (G) in the contralateral (CL) and ipsilateral (IL) hippocampi of caspase-3-deficient mouse brains 8 hours after H/I injury. In the ipsilateral hippocampus of a caspase-3-deficient mouse brain, a cleaved form appears intensely at ∼27 kDa but not at 18 kDa (F, middle), whereas an activated form of caspase-7 can be detected at ∼18 kDa under a longer exposure (F, right). These cleaved forms, along with the proform of caspase-7, correspond with those detected in a control lane (Cont) showing primary hepatocytes treated with tumor necrosis factor-α and actinomycin D for 6 hours (F, left). Scale bars: 10 μm (A); 30 μm (E).

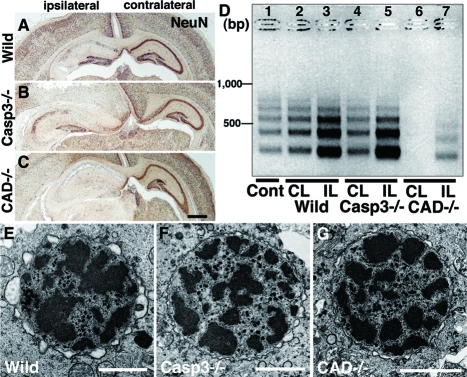

Caspase-Independent Pyramidal Neuron Death in the Hippocampus after H/I Injury Is Accompanied by DNA Fragmentation into Oligonucleosomes

To confirm further the presence of caspase-independent neuron death in the neonatal hippocampus after H/I injury, we used caspase-3-deficient and CAD-deficient mice.33,34,35,48 Genomic DNA fragmentation into oligonucleosomes is one of the hallmarks of apoptotic cell death and is mediated by CAD.49 Because programmed cell death occurred around P847 (Figure 1F), the genomic DNA from the untreated hippocampus of neonatal brains was weakly but distinctly fragmented into oligonucleosomes, as evidenced by an LMPCR method (Figure 2D, lane 1)43 DNA laddering occurred intensely in the ipsilateral side and weakly in the contralateral side of wild-type neonatal hippocampi after H/I injury (Figure 2D, lanes 2 and 3). Using CAD-deficient neonatal mice,33 we examined H/I injury-induced alterations in hippocampal pyramidal neurons and found that the degree of damage was similar to that in the wild-type mice 24 hours later (Figure 2, A and C). In this situation, DNA laddering was detectable in the ipsilateral hippocampus (Figure 2D, lane 7), indicating that nuclear DNA in the damaged neurons was fragmented by a DNase other than CAD. Moreover, no DNA laddering was observed in the contralateral hippocampus (Figure 2D, lane 6), suggesting that the DNA fragmentation of programmed neuron death is mediated in the wild-type neonatal hippocampus by CAD. As has been shown in caspase-3-deficient mice,44 H/I induced changes such as the appearance of shrunken neurons with pyknotic nuclei were abundant in each pyramidal layer of the hippocampus within 24 hours after H/I injury (Figure 2B; Figure 3, D and E). It has been suggested that long-term inhibition of caspase-3 during development by its genetic ablation up-regulates caspase-3-independent cell death pathways and increases the vulnerability of the developing brain to neonatal H/I injury.44 However, the DNA fragmentation in the ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampi of caspase-3-deficient mouse brains after H/I injury occurred similar to that in the wild-type mouse brains (Figure 2D, lanes 4 and 5). Because DNA laddering did not appear in the contralateral side of the CAD-deficient hippocampus after H/I injury, it is assumed that the DNA laddering detected in the contralateral side of the caspase-3-deficient hippocampus was mediated by CAD. It has been shown that caspase-7, which is structurally and functionally similar to caspase-3, compensates for the lack of caspase-3.48,50 In fact, cleaved caspase-7 was demonstrated in pyramidal neurons with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-stained shrunken nuclei in the contralateral hippocampus deficient in caspase-3 (Figure 3A). More interestingly, this cleaved caspase-7 was shown in numerous pyramidal neurons of the ipsilateral hippocampus after H/I injury by immunohistochemistry and in the ipsilateral hippocampus by Western blotting, although its immunoreactivity was somewhat weak (Figure 3, E and F). These results suggest that CAD that was activated by caspase-7 may be involved in the DNA ladder formation in caspase-3-deficient hippocampi after H/I injury. Furthermore, it has been shown by electron microscopy that small patches of chromatin clumping appear in the nuclei of pyramidal neurons in neonatal mice after H/I injury (Figure 2E).7 In the cases of caspase-3- and CAD-deficient mice, such chromatin clumping was also detected in pyramidal neurons within 24 hours after H/I injury (Figure 2, E and F). Collectively, these data suggest that neuron death in the pyramidal layers of the neonatal mouse hippocampus after H/I injury is mediated by both caspase-3-dependent and -independent pathways, in the latter of which the genomic DNA is weakly fragmented into oligonucleosomes by a DNase other than CAD.

Figure 2.

Pyramidal neuron death in the hippocampus of neonatal mouse brains after H/I injury. A–C: Coronal histological sections of wild-type (Wild) (A), caspase-3-deficient (Casp3−/−) (B), and CAD-deficient (CAD−/−) (C) brains including ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampi 24 hours after H/I injury. Staining with NeuN. D: Genomic DNA fragmentation detected by LMPCR. Samples were obtained from the hippocampus of an untreated wild-type brain (Cont) (lane 1), and the contralateral (CL) and ipsilateral (IL) hippocampi of wild-type (lanes 2 and 3), caspase-3-deficient (lanes 4 and 5), and CAD-deficient (lanes 6 and 7) brains 24 hours after H/I injury. E–G: A nucleus with small patches of chromatin clumping was observed in the pyramidal neurons of not only wild-type (E) but also caspase-3-deficient (F) and CAD-deficient (G) mouse hippocampi 8 hours after H/I injury. Scale bars: 500 μm (C); 2 μm (E–G).

Induction of Autophagy in Pyramidal Neurons of the Neonatal Hippocampus after H/I Injury

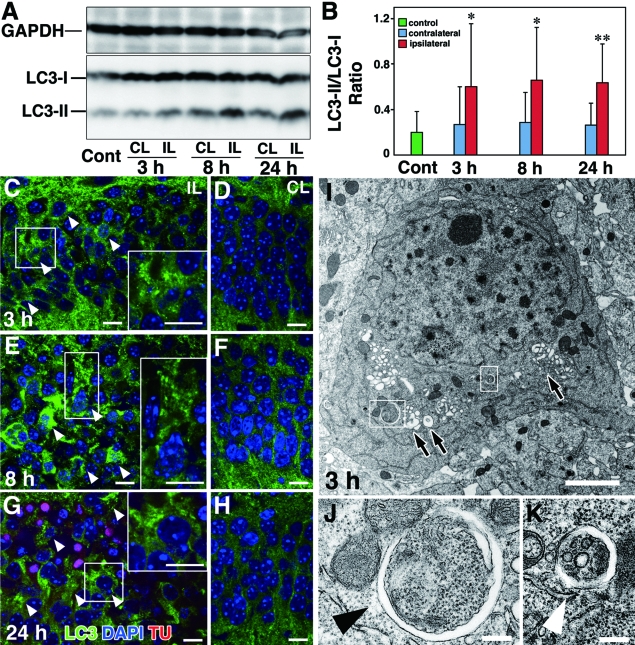

Although it is generally accepted that autophagy is essential for the maintenance of cellular metabolism and survival,16,17,18 it has also been demonstrated to be involved in cell death.19,25,26,51 To understand further whether autophagy is involved in hippocampal pyramidal neuronal damages after H/I injury, we examined alterations in amounts of LC3, a marker of autophagy.29 As shown in Figure 4, A and B, the amount of LC3-II increased in the ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampi of wild-type neonatal mice after the H/I insult, whereas the ratios of the amounts of LC3-II to LC3-I were significantly higher in the ipsilateral side of neonatal hippocampi at each time point than in the contralateral side and also than in the untreated control hippocampi. This tendency was also confirmed by double staining for LC3 and DAPI: intense LC3 staining appeared granular in the perikaryal region of pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus of the damaged side at 3, 8, and 24 hours (Figure 4, C, E, and G; Supplemental Figure 1 see http://ajp.amjpathol.org), whereas the pyramidal neurons in the contralateral side showed only weak staining for LC3 in the neuronal perikarya at the corresponding time points (Figure 4, D, F, and H; Supplemental Figure 1 see http://ajp.amjpathol. org). As evidenced by DAPI staining, the pyramidal neurons, in which granular immunodeposits for LC3 abundantly appeared in the ipsilateral side, frequently possessed shrunken or irregularly shaped nuclei with condensed or clumped chromatin (Figure 4, C, E, and G; Supplemental Figure 1 see http://ajp.amjpathol.org), indicating that such damaged neurons were mostly dying. Electron microscopic observations showed that neurons in the ipsilateral pyramidal layer of the neonatal hippocampus after H/I injury contained abundant autophagic vacuoles from an early stage, some of which were nascent autophagosomes with double-membrane structures (Figure 4, I and K). Such neurons also frequently contained nuclei with small patches of clumped chromatin (Figure 4I). These degenerating neurons increased in number with time after the H/I insult. As far as we observed hippocampal pyramidal neurons in the contralateral side after H/I injury, there were no neurons that possessed nuclei with small patches of chromatin clumping and autophagic vacuoles in the perikaryal region at any time examined (Supplemental Figure 2 see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Along these lines, however, dying neurons with typical apoptotic figures such as small nuclei with typical chromatin condensation and shrinkage of cell bodies could be detectable but were small in number (data not shown), reflecting the presence of programmed cell death at this postnatal period.47 These results suggest that autophagy is strongly induced in the neurons undergoing death in the pyramidal layer of the neonatal hippocampus after H/I injury.

Figure 4.

H/I injury induces autophagy in the hippocampi of wild-type neonatal mouse brains. A: Western blotting of LC3 in the untreated hippocampus (Cont) and the ipsilateral (IL) and contralateral (CL) hippocampi of neonatal mouse brains at 3, 8, and 24 hours after H/I injury. B: Quantification of A. The ratios of the amounts of LC3-II to LC3-I were calculated at each corresponding time. The final values represent the mean ± SD for three animals. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test) for the comparison of the values between the ipsilateral and contralateral sides. C–H: Triple staining of LC3, TUNEL (TU), and DAPI in the ipsilateral (C, E, G) and contralateral (D, F, H) hippocampi of neonatal mouse brains 3 (C, D), 8 (E, F) and 24 (G, H) hours after H/I injury. Intense granular staining for LC3 is indicated by arrowheads, and granular staining of LC3 in boxed areas are shown in insets (C, E, G). I–K: Electron micrographs of a CA1 pyramidal neuron in the hippocampi of wild-type neonatal mouse brains 3 hours after H/I injury. Abundant vacuolar structures (I, arrows) and nascent autophagosomes (I, boxed areas) (J and K, arrowheads) were detected in the perikarion. Scale bars: 10 μm (A–H); 3 μm (I); 0.5 μm (J, K).

Induction of autophagy after H/I injury was also shown in pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus deficient in caspase-3 or CAD, as evidenced by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy (Figure 5). As in wild-type neonatal mice, LC3 immunoreactivity was punctate in ipsilateral pyramidal neurons of the mutant mouse hippocampi after H/I injury (Figure 5, A and C; Supplemental Figure 1 see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Electron microscopic observations showed that autophagic vacuoles with single- or double-membrane structures abundantly appeared in the perikaryal region of the pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus of caspase-3- or CAD-deficient mouse brains after H/I injury (Figure 5, E–G), whereas dense chromatin profiles in nuclei of these neurons were similar to those detected in nuclei of wild-type pyramidal neurons after H/I injury (Figure 5E). The results also confirmed that autophagy is highly induced in the damaged pyramidal neurons of the ipsilateral hippocampus in caspase-3- and CAD-deficient mouse brains after H/I injury.

Figure 5.

Induction of autophagy in the hippocampus of neonatal mutant mouse brains after H/I injury. A–D: Triple staining of LC3, TUNEL (TU), and DAPI in the CA1 pyramidal layer of ipsilateral (A, C) and contralateral (B, D) hippocampi deficient in caspase-3 (Casp3−/−) (A, B) and CAD (CAD−/−) (C, D), respectively, 8 hours after H/I injury. Intense granular staining for LC3 is indicated by arrowheads, and granular staining of LC3 in boxed areas are shown in insets (A, C). E–G: Electron micrographs of pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus in mice deficient in caspase-3 (E, F) and CAD (CAD−/−) (G) obtained 3 hours after H/I injury. E and F: Pyramidal neuron containing vacuolar structures in the perikaryal region and showing numerous patches of chromatin clumping in the nucleus (E). Nascent autophagosomes that contained part of the cytoplasm and wrapped by endoplasmic reticulum-like tubular structures were abundantly observed in the boxed area of E (arrowheads in F). G: Part of the perikaryal area of a pyramidal neuron of the hippocampus in a CAD-deficient mouse showing a nascent autophagosome wrapped by an endoplasmic reticulum-like tubule (arrowhead). Scale bars: 10 μm (A–D); 3 μm (E); 1 μm (F and G).

Inhibition of H/I Induced-Neuron Death in the Neonatal Hippocampus by Atg7 Deficiency

We next investigated whether autophagy directly participates in the death of hippocampal pyramidal neurons after H/I insult, using mice that lack Atg7 specifically in the central nervous system (CNS) (Atg7flox/flox; nestin-Cre).36 Atg7 functions as an E1 enzyme in the Atg conjugation system and together with Atg3, an E2 enzyme, conjugates phosphatidyl ethanolamine to the C-terminal glycine residue of LC3-I, forming the membrane-bound form, LC3-II.52 Mice with an Atg7-deficiency in the CNS exhibit behavioral deficits and die at ∼8 weeks of age. Massive neuronal loss occurs in the cerebral and cerebellar cortices of these mutant mice, and inclusion bodies composed of polyubiquitinated proteins start to accumulate in the neurons at ∼3 weeks of age.36 To be certain that potential baseline CNS abnormalities in Atg7-mutant neonatal mice would not influence our results, we morphologically evaluated their CNS tissue from birth to 2 weeks of age, encompassing the experimental period of this study. Histological sections from Atg7 mutant mouse brains showed an intact, architecturally normal hippocampus, exhibiting no ubiquitin-positive inclusion bodies within neurons until after 2 weeks of life (Supplemental Figure 3, A–D, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

As expected, no Atg7 was detectable in the hippocampus of the CNS of Atg7-deficient mice; mice showed no conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II in the ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampi at P8, 1 day after H/I injury, by Western blotting; but Atg7 expression and conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II were normal in the hippocampi from control littermate brains (Supplemental Figure 3, E and F, see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). When the Atg7-deficient mice were subjected to H/I injury at P7 and neuronal morphology was assessed by histological analysis, TUNEL staining, and NeuN immunohistochemistry, 13 of 17 mice (76%) showed no pyknotic nuclei or positive TUNEL staining in the hippocampus 3 days later (Figure 6, A, C, E, and G). In contrast, only 22% of the littermate control mice (7 of 32 mice) escaped damage to the pyramidal neurons, and the rest had severely damaged hippocampal neurons (Figure 6, B, D, F, and H). For a more quantitative evaluation, the degree of damage 3 days after H/I injury was examined by measuring the ratio of the damaged areas to the total area of the pyramidal layer in the hippocampus (Figure 6I). The median value in Atg7-deficient mice (0.32) was significantly lower than that in littermate control mice (27.38) (P < 0.001). In addition, the degree of damage was also analyzed by subcategorizing severity of damage into four groups (0 to III). Among the Atg7-deficient brains, all but four were grade 0, and of these four, two each were grade I and grade II. By contrast, 9% of the control littermate brains showed damage at grade I, 9% at grade II, and 59% at grade III (Figure 6J).

Figure 6.

Atg7 deficiency prevents neuron death in the hippocampus of neonatal mouse brains 3 days after H/I injury. A–H: Saggital (A–D) and frontal (E–H) sections of the Atg7-deficient mouse brains (Atg7flox/flox; Nes) in the CNS (A, C, E, G) and its littermate (Atg7flox/flox) (B, D, F, H) 3 days after H/I injury. NeuN (A–F) and TUNEL (G, H) staining. Damaged areas in the hippocampus of A and B are shown in C and D and encircled by broken lines. I and J: Evaluation of damaged areas. I: Ratios (%) of damaged areas to the total areas in the hippocampal layers of Atg7-deficient (n = 17) and littermate control (n = 32) mouse brains 3 days after H/I injury. P < 0.001 (Mann-Whitney U-test for the comparison of the median values between the two groups). J: Incidence of hippocampal damage 3 days after H/I injury. The severity of the H/I injury was graded according to the number of TUNEL-positive neurons in the pyramidal layers of the hippocampus persection (less than 10 for grade 0, 11 to 100 for grade I, 101 to 200 for grade II, and more than 201 for grade III). The percentage of mice classified into each grade was determined from 17 Atg7 flox/flox; nestin-Cre (Atg7flox/flox; Nes), and 32 control littermate (Atg7flox/flox) mice. The number of mice belonging to each grade was described in the top of each bar. Scale bars: 500 μm (A, B, E, F); 50 μm (C, D); 100 μm (G, H, inset of G).

It has been shown that delayed neuronal death occurs in the pyramidal layers of the hippocampus and damaged pyramidal layers are replaced by glial cells within 7 days after ischemic insult.13 To exclude the possibility that the inhibition of autophagy simply delayed the onset of pyramidal neuron death in the hippocampus after H/I injury, we further analyzed the degree of damage in the neurons of the hippocampal pyramidal layers in Atg7-deficient and control littermate mouse brains 7 days after H/I injury. In fact, because shrunken or dying neurons with pyknotic nuclei were eliminated and the number of NeuN-positive surviving neurons was much reduced in the pyramidal layers of the control Atg7flox/flox mouse hippocampus 7 days after H/I injury, the pyramidal layers of the ipsilateral hippocampus were significantly diminished in area, compared to the contralateral hippocampus (Figure 7, B, D, F, and H). In Atg7-deficient mice, pyramidal neurons appeared intact in the hippocampus 7 days after H/I injury (Figure 7, A, C, E, and G). As far as we intensively measured the areas of the ipsi- and contralateral hippocampi 7 days after H/I injury, the area loss in the ipsilateral hippocampus that was expressed as a percentage of the contralateral hippocampal area was significantly much lower in the Atg7-deficient mice (14.0%) than in the littermate control mice (48.8%, P < 0.0001) (Figure 7I). These data indicate that the prevention of hippocampal pyramidal neuron death after H/I injury by Atg7 deficiency in CNS tissue is sustained at least until 7 days after H/I injury.

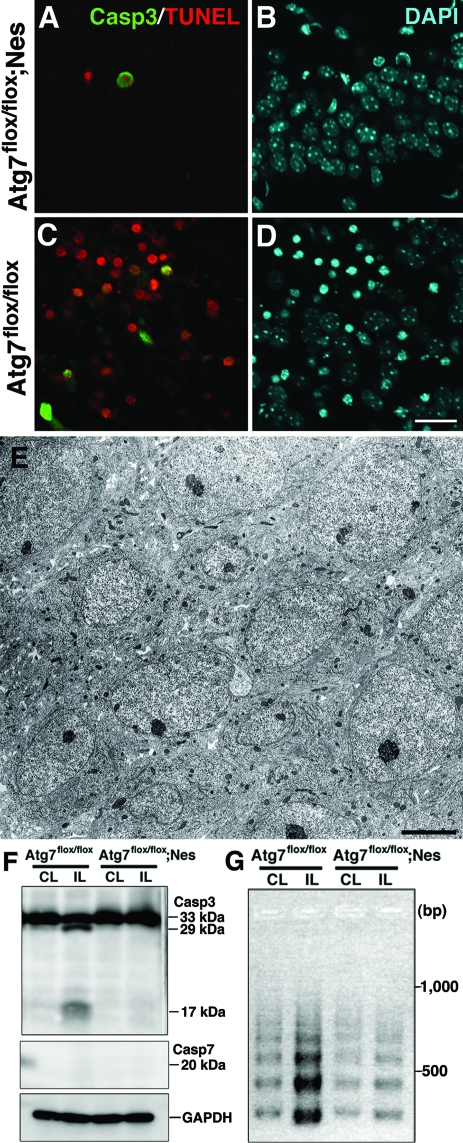

Pathological Alterations Are Not Detected in the Hippocampal Pyramidal Neurons of Atg7-Deficient Neonatal Hippocampus after H/I Injury

Because H/I induced-pyramidal neuron death in the neonatal hippocampus was primarily prevented by Atg7 deficiency, we next examined whether Atg7 deficiency prevents caspase-independent neuron death only or both caspase-dependent and -independent neuron death. Immunohistochemical observations revealed that only very rare TUNEL-positive neurons were co-stained for cleaved caspase-3 in the pyramidal layers of Atg7-deficient hippocampus 24 hours after H/I injury (Figure 8, A and B), whereas abundant TUNEL-positive pyramidal neurons, some of which were co-stained for cleaved caspase-3, appeared in the control littermate hippocampus at the corresponding time point (Figure 8, C and D). By electron microscopy, the neuronal architecture in the pyramidal layers of the hippocampus appeared intact in Atg7-deficient mice 24 hours after H/I injury (Figure 8E). By Western blotting, the active forms of caspases-3 and -7 were not detected in the hippocampus lacking Atg7 after H/I injury, although cleaved caspase-3 was detected in the control littermate hippocampus 8 hours after H/I injury (Figure 8F). Moreover, as evidenced by LMPCR, the genomic DNA from hippocampi of control littermate mice after H/I injury was intensely fragmented into nucleosomes in the ipsilateral side and faintly in the contralateral side, whereas that from the hippocampus of Atg7-deficient mice was faintly fragmented into nucleosomes in both the ipsilateral and contralateral sides (Figure 8G). Because certain numbers of neurons in the mouse hippocampus undergo naturally occurring cell death at P8,47 the DNA fragmentation observed in the contra- and ipsilateral hippocampi of Atg7-deficient mice might result from physiological neuron death in the hippocampus. Collectively, these results indicate that the Atg7 deficiency primarily prevented both caspase-3-dependent and caspase-3-independent neuron death in hippocampi from the neonatal mouse brains after H/I injury.

Figure 8.

The apoptotic pathway is inhibited in the neonatal hippocampus after H/I injury by the Atg7 deficiency. A–D: Triple staining for cleaved caspase-3 (Casp3) (A, C), TUNEL (A, C), and DAPI (B, D) in the ipsilateral hippocampi of Atg7-deficient (Atg7flox/flox; Nes) (A, B) and control littermate (Atg7flox/flox) (C, D) mouse brains 24 hours after H/I injury. E: The neuronal cell architecture as well as morphological features of the neurons appeared intact in the hippocampal pyramidal layer of an Atg7-deficient mouse brain 24 hours after H/I injury. F: Western blotting of caspases-3 and -7 in the ipsilateral (IL) and contralateral hippocampi of littermate control (Atg7flox/flox) and Atg7-deficient (Atg7flox/flox; Nes) mouse brains 8 hours after H/I injury. Cleaved caspase-3, but not caspase-7, was detected only in the control IL hippocampus. GAPDH was used as a loading control. G: The DNA fragmentation in the ipsilateral (IL) and contralateral (CL) hippocampi from Atg7-deficient (Atg7flox/flox; Nes) and littermate (Atg7flox/flox) mouse brains 24 hours after H/I injury. Scale bars: 20 μm (A–D); 5 μm (E).

Characteristic Features of H/I Injury-Induced Neuron Death in the Adult Hippocampus

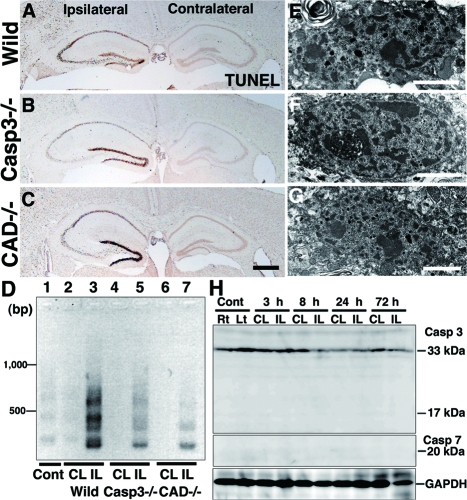

We were not able to use specifically the CNS tissue of Atg7-deicient mice to examine the role of autophagy in adult H/I brain injury, because neurodegeneration, such as loss of pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus and Purkinje cells in the cerebellum, manifests in the mutant mice from 3 weeks of age.36 As shown in Figure 9H, H/I injury-dependent pyramidal neuron death did not require activation of caspases-3 and -7 in the adult wild-type hippocampus. Like neonatal mice, it is also evident that such pyramidal neuron death was not prevented in the hippocampus of caspase-3- or CAD-deficient mouse brains (Figure 9, A–C), whereas DNA laddering in the ipsilateral hippocampi was detected in each of these mouse brains (Figure 9D), indicating that the DNA fragmentation in H/I injury-induced adult pyramidal neuron death was mediated by an unknown DNase other than CAD. Moreover, alterations in nuclear chromatin were very similar to those in neonatal hippocampal neurons after H/I injury (Figure 9, E–G). Autophagic alterations were also detected in pyramidal neurons of the adult hippocampus after H/I injury; the ratio of the amounts of LC3-II to LC3-I was significantly higher in the ipsilateral side at each time point than in the contralateral side (Figure 10, A and B), whereas intense granular LC3-imunoreactivity was observed in hippocampal pyramidal neurons with pyknotic nuclei after H/I injury (Figure 10, C and D; Supplemental Figure 1 see http://ajp.amjpathol.org). Notably autophagy seemed to be more pronounced in the ipsilateral hippocampus of adult mice than of neonates, judging from LC3-II/LC3-I ratio. By electron microscopy, pyramidal neurons that contained irregularly shaped nuclei with small patches of chromatin clumping often became shrunken and contained numerous vacuolar structures including autophagosomal and lysosomal structures (Figure 10, E–G), indicating that morphological features of these degenerating neurons resembled the features of type 2 neuron death.24 These results suggest that autophagy also plays a pivotal role in the H/I-induced pyramidal neuron death in the adult hippocampus.

Figure 9.

Pyramidal neuron death in the hippocampus of adult mouse brains after H/I injury. A–C: Frontal histological sections of wild-type (A), and caspase-3-deficient (Casp3−/−) (B) and CAD-deficient (CAD−/−) (C) brains including ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampi 24 hours after H/I injury. Staining with TUNEL. D: Genomic DNA fragmentation detected by LMPCR. Samples were obtained from the hippocampus of an untreated wild-type brain (Cont) (lane 1), and the contralateral (CL) and ipsilateral (IL) hippocampi of wild-type (lanes 2 and 3), caspase-3-deficient (lanes 4 and 5), and CAD-deficient (lanes 6 and 7) brains 24 hours after H/I injury. E–G: A nucleus with small patches of chromatin clumping was observed in the pyramidal neurons of not only wild-type (E) but also caspase-3-deficient (F) and CAD-deficient (G) mouse hippocampi 24 hours after H/I injury. H: The cleavage of caspases-3 and -7 in the contralateral (CL) and ipsilateral (IL) hippocampi of wild-type adult mouse brains at 3 hours, 8 hours, 24 hours, and 72 hours after H/I injury. Hippocampal tissues of the right (Rt) and left (Lt) sides from untreated adult mice were used as controls (Cont). Scale bars: 500 μm (C); 2 μm (E–G).

Figure 10.

H/I injury induces autophagy in the hippocampi of wild-type and mutant adult mouse brains. A: Western blotting of LC3 in the untreated hippocampus (Cont) and the ipsilateral (IL) and contralateral (CL) hippocampi of adult mouse brains at 3, 8, and 24 hours after H/I injury. B: Quantification of A. The ratios of the amounts of LC3-II to LC3-I were calculated at each corresponding time. The final values represent the mean ± SD for three animals. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test) for the comparison of the values between the ipsilateral and contralateral sides. C and D: Double staining of LC3 and DAPI in the ipsilateral (C) and contralateral (D) hippocampi of adult mouse brains 8 hours after H/I injury. E–G: Electron micrographs of a CA1 pyramidal neuron in the hippocampi of wild-type adult mouse brains 8 (E, F) and 24 (G) hours after H/I injury. Vacuolar structures with amorphous structures (arrows) are seen in E and F. F: A nascent autophagosome (arrowhead) (boxed areas in E). Scale bars: 10 μm (C, D); 3 μm (E, G); 0.5 μm (F).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that 1) H/I injury-induced pyramidal neuron death in the neonatal hippocampus occurred in caspase 3-dependent and caspase 3-independent manners. The caspase 3-independent neuron death in this model was accompanied by DNA ladder formation that was mediated by unknown DNase other than CAD. 2) H/I injury induced autophagy in neonatal hippocampal pyramidal neurons, whereas this pyramidal neuron death was prevented by Atg7 deficiency. 3) Pyramidal neuron death in the adult hippocampus after H/I injury was caspase-independent and accompanied by autophagosome formation.

Pyramidal Neuron Death in the Neonatal Hippocampus after H/I Injury

Because numerous studies on neuron death after H/I brain injury using various animals have shown that the hippocampus is the most vulnerable to ischemic insult,9,13 we examined how pyramidal neurons in the neonatal and adult hippocampi die after H/I injury. As shown in the Results section, nuclei of most pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus became pyknotic within 24 hours after H/I injury, indicating that the dying neurons were distinct from necrosis. It has been shown that caspase-3 may mediate ischemic neuron death in the rodent hippocampus.10,13,53 In fact, we confirmed that 35% of total hippocampal pyramidal neurons underwent neuron death in a caspase-dependent manner. The ratio of neurons that died in a caspase-dependent manner is consistent with previous data shown by the use of a caspase-3 inhibitor44 and Bcl-xL-overexpressing mice.14 Although H/I injury-induced pyramidal neuron death in the neonatal hippocampus was in part caspase-dependent,10,13 the genetic ablation of caspase-3 did not prevent H/I injury-induced pyramidal neuron death.44 It has been shown that caspase-7, which is structurally and functionally similar to caspase-3, compensates for the lack of caspase-3.48,50 In fact, in our H/I injury model using caspase-3-deficient mice, caspase-7 was activated in pyramidal neurons that underwent programmed cell death in the contralateral hippocampus at P8 (Figure 3A) and also weakly, but distinctly, in the pyramidal neurons of the ipsilateral hippocampus after H/I injury (Figure 3, E and F). Therefore, it seems likely that CAD in caspase-3-deficient mouse brains after H/I injury was activated by caspase-7 that was up-regulated in a compensatory way, resulting in DNA laddering.50

As shown in the present results, it is well known that a great number of pyramidal neurons in the neonatal hippocampus after H/I injury die in a caspase-independent manner.10 To verify the involvement of this caspase-independent pathway in H/I injury-induced pyramidal neuron death in addition to the caspase-dependent pathway, neonatal CAD-deficient mice were subjected to H/I brain injury. Like caspase-3-deficient mice, H/I injury-induced pyramidal neuron death in the neonatal hippocampus was not prevented by CAD deficiency. It is very interesting that even in CAD-deficient mice, pyramidal neuron death in the hippocampus after H/I injury that was caspase-independent was accompanied by genomic DNA laddering, indicating that this DNA fragmentation was mediated by an unknown DNase other than CAD. Collectively, H/I injury-induced pyramidal neuron death in the neonatal hippocampus was mediated by both caspase- dependent and -independent pathways.

Involvement of Autophagy in Neonatal Pyramidal Neuron Death after H/I Injury

This is the first report that we are aware of providing direct evidence for autophagy-induced neuron death after neonatal mouse H/I brain injury, using mice that cannot execute autophagy specifically in CNS tissue.36 As stated above, we demonstrated that pyramidal neuron death in the neonatal hippocampus after H/I injury was executed in both caspase-dependent and -independent manners, as has been shown previously.10,44 Surprisingly, such caspase-dependent neuron death after H/I injury, along with caspase-independent neuron death, was prevented by selective CNS Atg7 deficiency. It has also been shown that autophagy participates in the initiation of apoptotic cell death such as photoreceptor cells exposed to oxidative stress and cerebellar granule cells after deprivation of serum and potassium.23,54 As has been noted,30 if autophagy would act as a survival factor in response to various stresses, hippocampal pyramidal neurons deficient in Atg7 would not be resistant to H/I injury. It is therefore important to reveal the molecular mechanism of how autophagy is involved in the activation of caspase cascade in H/I injury-induced pyramidal neuron death. These lines of evidence suggest that once H/I injury induces autophagy in pyramidal neurons of the neonatal hippocampus, autophagy may further activate two effectors, caspase-dependent (apoptotic) and -independent pathways of neuron death.

It has been shown that specific inhibitors of caspases attenuate H/I-induced pyramidal neuron death in the neonatal hippocampus.44,53 Because there were caspase-dependent and -independent pathways of hippocampal pyramidal neuron death after neonatal brain H/I injury, the suppressive effects of these chemical agents and genetic manipulation such as Bcl-xL14 would be limited to some extent. Thus far, chemical and genetically manipulated suppressors of autophagy that are available for therapeutic use have not been generated. Therefore, like caspase inhibitors, the development of chemical tools that prevent autophagic neuron death by specifically blocking each step of autophagy55 may be important, because our data strongly suggest that autophagy regulates H/I-induced pyramidal neuron death in the neonatal hippocampus.

H/I Injury-Induced Pyramidal Neuron Death in the Adult Hippocampus Is Prevented by Neither Caspase-3 Nor CAD Deficiency

The present data using caspase-3- or CAD-deficient mice also provide direct evidence that H/I injury-induced pyramidal neuron death in the adult hippocampus does not require the activation of caspase-3 and CAD. Such neuron death in the adult hippocampus was accompanied by pyknosis and genomic DNA fragmentation into oligonucleosomes, indicating that pyramidal neuron death in the adult hippocampus after H/I injury is caspase-3-independent and distinct from necrosis. The present study could not examine the role of autophagy in adult H/I brain injury, because Atg7flox/flox; nestin-Cre mice manifested neurodegenerative signs such as loss of pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus and Purkinje cells in the cerebellum from 3 weeks of age.36 Nevertheless, our current data showing that morphological features of degenerating neurons in the adult hippocampus after H/I injury resembled the features of type 2 neuron death,24 suggest that autophagy is also involved in the execution of H/I injury-induced neuron death in the adult hippocampus. Thus, therapeutic strategies to inhibit autophagy-induced neuron death may prove beneficial in the treatment of both pediatric and adult H/I brain injury.

Collectively, at present, it remains unknown how the genetic ablation of Atg7 specifically in the CNS prevents H/I injury-induced pyramidal neuron death in the neonatal hippocampus. It is well known that autophagy is essential for the maintenance of cellular metabolism and is induced in response to various stresses such as starvation, thus preventing cells from dying.18 It is therefore very important to understand the mechanism of how pyramidal neurons regulate the two opposite downstream effects of autophagy, survival and death, after H/I insult.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Ikeue, K. Ohta, A. Koseki, and K. Isahara for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Yasuo Uchiyama, Department of Cell Biology and Neurosciences, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, 2-2 Yamadaoka, Suita, Osaka 565-0871, Japan. E-mail: y-uchi@anat1. med.osaka-u.ac.jp.

See related Commentary on page 284

Supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, Japan (grant-in-aid for scientific research 16GS0315 to Y.U., M.S., and M.K.).

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp. amjpathol.org.

References

- du Plessis AJ, Volpe JJ. Perinatal brain injury in the preterm and term newborn. Curr Opin Neurol. 2002;15:151–157. doi: 10.1097/00019052-200204000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamrick SE, Ferriero DM. The injury response in the term newborn brain: can we neuroprotect? Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:147–154. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000063775.81810.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashwal S, Pearce WJ. Animal models of neonatal stroke. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2001;13:506–516. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200112000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferriero DM. Neonatal brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1985–1995. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagberg H, Bona E, Gilland E, Puka-Sundvall M. Hypoxia-ischaemia model in the 7-day-old rat: possibilities and shortcomings. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 1997;422:85–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb18353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S. Anoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in rats. Am J Pathol. 1960;36:1–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon RA, Hall JJ, Noble LJ, Ferriero DM. Delayed cell death in neonatal mouse hippocampus from hypoxia-ischemia is neither apoptotic nor necrotic. Neurosci Lett. 2001;304:165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01788-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomgren K, Leist M, Groc L. Pathological apoptosis in the developing brain. Apoptosis. 2007;12:993–1010. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0754-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon RA, Sedik C, Ferriero DM. Strain-related brain injury in neonatal mice subjected to hypoxia-ischemia. Brain Res. 1998;810:114–122. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00892-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Wang X, Xu F, Bahr BA, Shibata M, Uchiyama Y, Hagberg H, Blomgren K. The influence of age on apoptotic and other mechanisms of cell death after cerebral hypoxia-ischemia. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12:162–176. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert JW, Zhang JH. Pathophysiology of an hypoxic-ischemic insult during the perinatal period. Neurol Res. 2005;27:246–260. doi: 10.1179/016164105X25216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson ME, Han BH, Choi J, Knudson CM, Korsmeyer SJ, Parsadanian M, Holtzman DM. BAX contributes to apoptotic-like death following neonatal hypoxia-ischemia: evidence for distinct apoptosis pathways. Mol Med. 2001;7:644–655. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness JM, Harvey CA, Strasser A, Bouillet P, Klocke BJ, Roth KA. Selective involvement of BH3-only Bcl-2 family members Bim and Bad in neonatal hypoxia-ischemia. Brain Res. 2006;1099:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsadanian AS, Cheng Y, Keller-Peck CR, Holtzman DM, Snider WD. Bcl-xL is an antiapoptotic regulator for postnatal CNS neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:1009–1019. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-03-01009.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman JM. Intervention strategies for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic cerebral injury. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Waguri S, Ueno T, Iwata J, Murata S, Tanida I, Ezaki J, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E, Tanaka K, Chiba T. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:425–434. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakaya H, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y, Tokuhisa T, Mizushima N. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature. 2004;432:1032–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature03029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy in health and disease: a double-edged sword. Science. 2004;306:990–995. doi: 10.1126/science.1099993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JH, Horbinski C, Guo F, Watkins S, Uchiyama Y, Chu CT. Regulation of autophagy by extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases during 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium-induced cell death. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:75–86. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon RA. Autophagy in neurodegenerative disease: friend, foe or turncoat? Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:528–535. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike M, Shibata M, Waguri S, Yoshimura K, Tanida I, Kominami E, Gotow T, Peters C, von Figura K, Mizushima N, Saftig P, Uchiyama Y. Participation of autophagy in storage of lysosomes in neurons from mouse models of neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinoses (Batten disease). Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1713–1728. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61253-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CT. Autophagic stress in neuronal injury and disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:423–432. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000229233.75253.be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canu N, Tufi R, Serafino AL, Amadoro G, Ciotti MT, Calissano P. Role of the autophagic-lysosomal system on low potassium-induced apoptosis in cultured cerebellar granule cells. J Neurochem. 2005;92:1228–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke PG. Developmental cell death: morphological diversity and multiple mechanisms. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1990;181:195–213. doi: 10.1007/BF00174615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsawa Y, Isahara K, Kanamori S, Shibata M, Kametaka S, Gotow T, Watanabe T, Kominami E, Uchiyama Y. An ultrastructural and immunohistochemical study of PC12 cells during apoptosis induced by serum deprivation with special reference to autophagy and lysosomal cathepsins. Arch Histol Cytol. 1998;61:395–403. doi: 10.1679/aohc.61.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchiyama Y. Autophagic cell death and its execution by lysosomal cathepsins. Arch Histol Cytol. 2001;64:233–246. doi: 10.1679/aohc.64.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitatori T, Sato N, Waguri S, Karasawa Y, Araki H, Shibanai K, Kominami E, Uchiyama Y. Delayed neuronal death in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer of the gerbil hippocampus following transient ischemia is apoptosis. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1001–1011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01001.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Xu F, Wang X, Shibata M, Uchiyama Y, Blomgren K, Hagberg H. Different apoptotic mechanisms are activated in male and female brains after neonatal hypoxia-ischaemia. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1016–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Yuan J. Autophagy in cell death: an innocent convict? J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2679–2688. doi: 10.1172/JCI26390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice JE, III, Vannucci RC, Brierley JB. The influence of immaturity on hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in the rat. Ann Neurol. 1981;9:131–141. doi: 10.1002/ana.410090206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Kretz O, Gass P, Anlag K, Orban PC, Bock R, Klein R, Schutz G. Disruption of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in the nervous system results in reduced anxiety. Nat Genet. 1999;23:99–103. doi: 10.1038/12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawane K, Fukuyama H, Yoshida H, Nagase H, Ohsawa Y, Uchiyama Y, Okada K, Iida T, Nagata S. Impaired thymic development in mouse embryos deficient in apoptotic DNA degradation. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:138–144. doi: 10.1038/ni881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuida K, Zheng TS, Na S, Kuan C, Yang D, Karasuyama H, Rakic P, Flavell RA. Decreased apoptosis in the brain and premature lethality in CPP32-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;384:368–372. doi: 10.1038/384368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard JR, Klocke BJ, D’Sa C, Flavell RA, Roth KA. Strain-dependent neurodevelopmental abnormalities in caspase-3-deficient mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:673–677. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.8.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Waguri S, Chiba T, Murata S, Iwata J, Tanida I, Ueno T, Koike M, Uchiyama Y, Kominami E, Tanaka K. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Dono K, Gotoh K, Shibata M, Koike M, Marubashi S, Miyamoto A, Takeda Y, Nagano H, Umeshita K, Uchiyama Y, Monden M. Participation of autophagy in the degeneration process of rat hepatocytes after transplantation following prolonged cold preservation. Arch Histol Cytol. 2005;68:71–80. doi: 10.1679/aohc.68.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanida I, Mizushima N, Kiyooka M, Ohsumi M, Ueno T, Ohsumi Y, Kominami E. Apg7p/Cvt2p: a novel protein-activating enzyme essential for autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:1367–1379. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.5.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike M, Nakanishi H, Saftig P, Ezaki J, Isahara K, Ohsawa Y, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Watanabe T, Waguri S, Kametaka S, Shibata M, Yamamoto K, Kominami E, Peters C, von Figura K, Uchiyama Y. Cathepsin D deficiency induces lysosomal storage with ceroid lipofuscin in mouse CNS neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6898–6906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06898.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike M, Shibata M, Ohsawa Y, Nakanishi H, Koga T, Kametaka S, Waguri S, Momoi T, Kominami E, Peters C, Figura K, Saftig P, Uchiyama Y. Involvement of two different cell death pathways in retinal atrophy of cathepsin D-deficient mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;22:146–161. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavrieli Y, Sherman Y, Ben-Sasson SA. Identification of programmed cell death in situ via specific labeling of nuclear DNA fragmentation. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:493–501. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin BJK. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press,; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Staley K, Blaschke AJ, Chun J. Apoptotic DNA fragmentation is detected by a semi-quantitative ligation-mediated PCR of blunt DNA ends. Cell Death Differ. 1997;4:66–75. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West T, Atzeva M, Holtzman DM. Caspase-3 deficiency during development increases vulnerability to hypoxic-ischemic injury through caspase-3-independent pathways. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;22:523–537. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaunig JE, Goldblatt PJ, Hinton DE, Lipsky MM, Chacko J, Trump BF. Mouse liver cell culture. I. Hepatocyte isolation. In Vitro. 1981;17:913–925. doi: 10.1007/BF02618288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reznikov KY. Cell proliferation and cytogenesis in the mouse hippocampus. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 1991;122:1–74. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-76447-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakhani SA, Masud A, Kuida K, Porter GA, Jr, Booth CJ, Mehal WZ, Inayat I, Flavell RA. Caspases 3 and 7: key mediators of mitochondrial events of apoptosis. Science. 2006;311:847–851. doi: 10.1126/science.1115035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enari M, Sakahira H, Yokoyama H, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Nagata S. A caspase-activated DNase that degrades DNA during apoptosis, and its inhibitor ICAD. Nature. 1998;391:43–50. doi: 10.1038/34112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houde C, Banks KG, Coulombe N, Rasper D, Grimm E, Roy S, Simpson EM, Nicholson DW. Caspase-7 expanded function and intrinsic expression level underlies strain-specific brain phenotype of caspase-3-null mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9977–9984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3356-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Alva A, Su H, Dutt P, Freundt E, Welsh S, Baehrecke EH, Lenardo MJ. Regulation of an ATG7-beclin 1 program of autophagic cell death by caspase-8. Science. 2004;304:1500–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1096645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanida I, Tanida-Miyake E, Komatsu M, Ueno T, Kominami E. Human Apg3p/Aut1p homologue is an authentic E2 enzyme for multiple substrates. GATE-16, GABARAP, and MAP-LC3, and facilitates the conjugation of hApg12p to hApg5p. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13739–13744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200385200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Deshmukh M, D’Costa A, Demaro JA, Gidday JM, Shah A, Sun Y, Jacquin MF, Johnson EM, Holtzman DM. Caspase inhibitor affords neuroprotection with delayed administration in a rat model of neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1992–1999. doi: 10.1172/JCI2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunchithapautham K, Rohrer B. Apoptosis and autophagy in photoreceptors exposed to oxidative stress. Autophagy. 2007;3:433–441. doi: 10.4161/auto.4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein DC, Gestwicki JE, Murphy LO, Klionsky DJ. Potential therapeutic applications of autophagy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:304–312. doi: 10.1038/nrd2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]