Summary

Objective

To study the career destinations, job satisfaction and views of UK-trained senior doctors.

Design

Postal questionnaire.

Setting

All doctors who qualified from all UK medical schools in 1977; and Department of Health employment data.

Main outcome measures

Career destinations of medical qualifiers from 1977.

Results

72% responded to the questionnaire. Using all available evidence, including that on non-responders, 76% of the cohort, comprising 77% of the men and 74% of the women, were working in the NHS 27 years after qualification. Approximately 18% were in medical jobs either overseas or outside the NHS. Of respondents in the NHS, 89% of men and 51% of women had full-time contracts. NHS doctors rated their job satisfaction highly, with a median score of 19.5 on a scale from 5 (very low satisfaction) to 25 (very high satisfaction). Satisfaction with time off for leisure was much lower, with a median score of 4.6 on a scale from 1 (low) to 10 (high). Of those in the NHS, 67% agreed that they worked longer hours than they thought they should; and 40% agreed that their working conditions were satisfactory.

Conclusions

27 years after qualification, the percentage of women who were working in the NHS was similar to that of men. Although these senior doctors had high levels of satisfaction with the content of their jobs, they were not so satisfied with their working hours and working conditions. Our results can be used as benchmarks, against which the career pathways and satisfaction levels of more recently qualified doctors can be compared.

Introduction

Surveys of senior doctors can provide important insights into doctors' career destinations, job satisfaction, views about their jobs and future plans. We report on a survey of the qualifiers of 1977 from all UK medical schools – as an example of a cohort of doctors from the 1970s – conducted in 2004. In this paper, we focus on career destinations, job satisfaction and views. In an accompanying paper,1 we report on the doctors' future plans.

Methods

Procedure and population

Since 1975, the UK Medical Careers Research Group has followed the careers of UK doctors by conducting regular postal questionnaire surveys. The Group surveys cohorts of doctors, each consisting of all qualifiers from all UK medical schools in a selected year, at regular intervals after graduation. Our survey methods have been reported in detail elsewhere.2 The starting point for each of our surveys is the cohort of qualifiers as it was in the first year after qualification (excluding a small number who do not wish to participate). In 1978, the General Medical Council provided a list of all UK medical qualifiers and their addresses. In successive surveys since then, we have tried to trace all the original members of the cohort. Updated addresses have been obtained from the respondents themselves in the course of previous surveys, and from current editions of the Medical Register and the Medical Directory.

The survey instrument

The questionnaire comprised structured, ‘closed’ questions and statements, a few ‘open’ questions, and a request for ‘free text’ comments on any aspect of the respondents' career or work. Topics covered by our questionnaire included current employment, previous jobs since our last survey, levels of satisfaction with their job and with time available for leisure activities, views about different aspects of their jobs, future career plans and retirement intentions.

The statements used to assess job satisfaction and satisfaction with time available for leisure, and the calculation of scores based on them are described in Appendix A. To assess doctors' views on working conditions and career opportunities, we invited them to respond to various attitude statements by scoring their views on a five-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

Definitions and data analysis

We focus mainly on respondents who were working in the NHS, defined as holding either a substantive or an honorary NHS contract (the latter are predominantly those with substantive clinical academic posts). In the analysis, we aggregate specialties into broad groups based on those initially defined in the Todd Report.3

Response rates, demographic data and details about posts held were summarised using descriptive statistics. Differences in the distribution of career destinations were assessed using χ2 tests. Distributions of job satisfaction and leisure satisfaction scores were compared using Mann-Whitney U tests. In making multiple similar comparisons, we regarded the attainment of a significance threshold of p≤0.01 as evidence of significant difference.

Data from the Department of Health's employment record; capture-recapture analysis

As we have done previously,4 data about whether the doctors were currently employed in the NHS were obtained from the Department of Health's employment record. These data, and those from our survey, were analysed using capture-recapture methods.5 The combined data provide a more reliable whole-cohort estimate of NHS participation than that available from either dataset alone. We have previously demonstrated6 that this method produces results which are consistent with those obtained by exhaustive tracing of non-respondents by personal follow-up.

Results

Response rates

In 1977, 3135 doctors qualified in the UK. Of these, 67.5% (2116) were men and 32.5% (1019) were women. 54 are known by us to have died, 36 declined to participate in the survey, and 2180 responded, giving an effective response rate of 72% (2180/3045), comprising 69.7% (1430/2051) of men and 75.5% (750/994) of women. The mean and median age of the 1977 cohort at the time of the survey was 51 years.

Career destinations of respondents

Of respondents, 97.3% (2118 doctors) were in medical jobs, comprising 92.6% (2017) who were in the UK and 4.6% (101) who were overseas; 86.7% (1888) were in NHS medical practice; 5.9% (129) were in other UK medical jobs; 0.6% (13) were in non-medical jobs; and 2.1% (46) were not in paid employment. Three doctors provided information that we could not classify and were omitted from these calculations.

Of the 1888 doctors in the NHS, 50.2% (948) were in hospital practice, 45.8% (864) in general practice, and 4.0% (76) in public health medicine or community health. 54.5% of the men and 41.8% of the women were in hospital practice; 43.6% of the men and 49.6% of the women were in general practice; and 1.7% of the men and 8.6% of the women were in public health medicine or community health. Comparing the NHS doctors in these broad career destinations, the differences between men and women were significant (χ22=67.5, p<0.001). The percentages of men and women working in medical jobs, but not in the NHS, were similar (men 10.7%, women 10.3% of all respondents).

As shown above, a significantly and substantially higher percentage of men than women respondents were in NHS hospital practice. Furthermore, considering specialty destinations within NHS hospital practice, there were also significant differences between men and women (χ210=77.0, p<0.001). For this calculation we included the 11 hospital specialty groups listed in Table 1, that is, all of the categories listed under ‘UK NHS’ except general practice, community health and public health medicine (comprising 682 male and 266 female respondents). The specialties that showed significant male-female differences, based on analysis of adjusted residuals, were the surgical specialties (25.7% of the men were in hospital practice, 5.6% of the women), paediatrics (4.8% of men, 8.6% of women), pathology (8.7% of men, 13.2% of women) and psychiatry (7.3% of men, 19.2% of women).

Table 1.

Career destinations of the respondents from the cohort of UK qualifiers of 1977 (percentages of all respondents and numbers of doctors)

| Men | Women | Total | Men | Women | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | No | No | No | |

| Responders in medical employment | ||||||

| UK NHS: | ||||||

| General practice | 38.3 | 42.3 | 39.7 | 548 | 316 | 864 |

| Hospital medical specialties | 10.6 | 7.1 | 9.4 | 152 | 53 | 205 |

| Surgical specialties | 12.2 | 2.0 | 8.7 | 175 | 15 | 190 |

| Paediatrics | 2.3 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 33 | 23 | 56 |

| Accident & emergency | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 14 | 4 | 18 |

| Obstetrics & gynaecology | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 27 | 17 | 44 |

| Anaesthetics | 6.6 | 4.7 | 6.0 | 95 | 35 | 130 |

| Radiology | 3.2 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 46 | 16 | 62 |

| Clinical oncology | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 13 | 8 | 21 |

| Pathology | 4.1 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 59 | 35 | 94 |

| Psychiatry | 3.5 | 6.8 | 4.6 | 50 | 51 | 101 |

| Community health | 0.3 | 5.0 | 1.9 | 5 | 37 | 42 |

| Public health medicine | 1.1 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 16 | 18 | 34 |

| Other clinical specialties* | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 18 | 9 | 27 |

| Total in the NHS | 87.5 | 85.3 | 86.7 | 1251 | 637 | 1888 |

| UK medicine outside the NHS | 5.7 | 6.4 | 5.9 | 81 | 48 | 129 |

| Medicine abroad | 5.0 | 3.9 | 4.6 | 72 | 29 | 101 |

| Hospital practice | 3.8 | 2.1 | 3.3 | 55 | 16 | 71 |

| General practice | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 15 | 11 | 26 |

| Total in medical employment | 98.2 | 95.6 | 97.3 | 1404 | 714 | 2118 |

| Responders not in medical employment | ||||||

| Non-medical employment | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 9 | 4 | 13 |

| Not in paid employment | 1.2 | 3.9 | 2.1 | 17 | 29 | 46 |

| ALL RESPONDENTS† | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1430 | 747 | 2177 |

Percentages may not add up exactly owing to rounding.

Includes doctors known to be working in medicine but who did not state their specialty.

3 women respondents did not provide details of their employment and have been omitted from the table.

Career destinations of the whole cohort, using capture-recapture analysis and revised calculations

We used capture-recapture analysis (see Method) to obtain a more precise estimate of the percentage of the whole cohort working in the NHS in 2004. Including the 54 doctors in the cohort who were known to have died in the calculation, we estimated that 76.1% (95% CI: 75.5–76.7%) of the original cohort of 3135 were working in the NHS. The estimate for men was 76.9% (95% CI 76.2%–77.7%) and for women 74.1% (95% CI: 73.2–75.1%). Excluding these 54, we estimated that 77.4% (95% CI: 76.8–78.0%) of the survivor cohort of 3135 were working in the NHS (men 78.4% [95% CI 77.6– 79.2%], women 75.1% [95% CI: 74.2– 76.1%]).

In Table 2 we give our best estimates of the career destinations of the whole cohort, not just the responders, expressed per hundred original qualifiers. The basis of the calculations is given in Appendix B. These revised estimates suggest that, of the whole cohort, about 94% were working in medical jobs, with 4% currently not employed in medicine and 2% deceased.

Table 2.

Career destinations 27 years after qualification: hypothetical cohort of 100 UK qualifiers of 1977 incorporating all available information about non-respondents and respondents

| Specialty group | Men | Women | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK NHS: | |||

| General practice | 34 | 37 | 35 |

| Hospital medical specialties | 9 | 6 | 8 |

| Surgical specialties | 11 | 2 | 8 |

| Paediatrics | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Accident & emergency | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Obstetrics & gynaecology | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Anaesthetics | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| Radiology | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Clinical oncology | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Pathology | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Psychiatry | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| Community health | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Public health medicine | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Other clinical specialties | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| All in the NHS | 77 | 74 | 76 |

| Estimated whole time equivalent | 73 | 56 | 67 |

| OTHERS | |||

| Employed in medicine | 18 | 17 | 18 |

| Not employed in medicine | 3 | 8 | 4 |

| Deceased | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| ALL RESPONDENTS | 100 | 100 | 100 |

See Appendix B for assumptions and calculations.

Other posts held by respondents

We asked the doctors to tell us about other posts held, in addition to their main specialty. 133 respondents were medical directors/clinical directors in NHS Trusts, clinical directorates or other NHS organisations. 29 were PEC members or PEC chairs (PECs are Professional Executive Committees in Primary Care Trusts in the UK). 45 held other substantive roles in Primary Care Trusts (e.g. PCT Clinical Governance Lead, PCT board member, PCT chair/committee member, PCT Research and Development Lead). 14 respondents were medical school deans, postgraduate deans, or associate deans.

Full-time and part-time working

In both the NHS and overall, about a quarter of the doctors who told us about their working pattern worked part-time (those in the NHS: 24.0% [421/1752]; all in medical employment: 24.7% [482/1955]). Of the 1284 men in medical posts who told us, 88.6% were working full-time in their current post and 11.4% were working part-time. Of the men in the NHS who told us about their working pattern, 89.2% worked full-time. Of the 671 women in medical posts who told us, 49.9% worked full-time and 50.1% worked part-time; and, of those in the NHS, 50.7% worked full-time.

Table 3.

Full-time and part-time working for doctors in medical employment (numbers of doctors, percentages of respondents at each level)

| Men | Women | Total | Men | Women | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occupational group | % | % | % | n | n | n |

| WORKING PATTERN: | ||||||

| Full-time | 88.6 | 49.9 | 75.3 | 1138 | 335 | 1473 |

| Part-time | 11.4 | 50.1 | 24.7 | 146 | 336 | 482 |

| All | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 1284 | 671 | 1955 |

| WORKING PATTERN UK NHS: | ||||||

| Full-time | 89.2 | 50.7 | 76.0 | 1026 | 305 | 1331 |

| Part-time | 10.8 | 49.3 | 24.0 | 124 | 297 | 421 |

| Hospital (full-time) | 89.1 | 57.8 | 80.0 | 542 | 144 | 686 |

| Hospital (part-time) | 10.9 | 42.3 | 20.0 | 66 | 105 | 171 |

| General practice (full-time) | 88.9 | 46.2 | 73.3 | 466 | 140 | 606 |

| General practice (part-time) | 11.1 | 53.8 | 26.7 | 58 | 163 | 221 |

1955/2118 (92.3%) of those in medical posts and 1752/1888 (92.8%) of those working in the NHS told us their working pattern.

Achievement of senior career posts

In NHS general practice, 98.0% (534) of the men and 91.4% (288) of the women were principals (χ21=18.8, p<0.001). In NHS hospital practice, 98.0% (653) of the men and 73.6% (220) of the women were consultants (χ21=140.4, p<0.001). Of women working in hospital practice but not in consultant posts, 19.1% (57) held non consultant career grades and 7.4% (22) held other hospital posts.

Comparisons between early career choice and eventual destination

We compared respondents' original first choice of specialty at one, three and five years after qualification (i.e. what they had told the Medical Careers Research Group about their career hopes in 1978, 1980 and 1982) with their eventual specialty 27 years after qualification in 2004 (Table 4). Taking all specialty groups together, 50.3% of respondents who chose each specialty group in year one were eventually working in it in year 27. Of those who chose each specialty group in years three and five, 70.0% and 78.1% respectively were eventually working in it at year 27.

Table 4.

Early career choices and eventual destinations: percentage of the cohort who chose each specialty at years one, three and five after qualification, and who were working in it at year 27

| Total | Men | Women | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chosen mainstream | Yr 1 | Yr 3 | Yr 5 | Yr 1 | Yr 3 | Yr 5 | Yr 1 | Yr 3 | Yr 5 | |||||||||

| General practice | 71.1 | 78.3 | 83.4 | 74.7 | 83.2 | 88.2 | 66.1 | 71.2 | 76.0 | |||||||||

| Specialist practice | 39.1 | 63.8 | 74.0 | 42.7 | 69.0 | 79.6 | 31.2 | 52.2 | 61.9 | |||||||||

| Medical specialties | 32.8 | * | 54.4 | ** | 71.6 | 36.4 | * | 58.9 | ** | 76.9 | 23.5 | 39.7 | 53.1 | |||||

| Paediatrics | 25.9 | ** | 53.3 | 68.6 | 29.9 | 63.9 | 78.8 | 22.2 | 43.6 | 59.5 | ||||||||

| Surgical specialties | 47.8 | ** | 71.6 | * | 83.3 | ** | 50.0 | * | 73.2 | 84.3 | 29.7 | 58.3 | 73.7 | |||||

| Obstetrics & gynaecology | 30.9 | 63.8 | 82.6 | 33.1 | 73.1 | 96.0 | 28.6 | 52.4 | 66.7 | |||||||||

| Anaesthetics | 56.3 | ** | 76.3 | ** | 80.1 | 57.1 | * | 83.3 | ** | 86.4 | 54.8 | ** | 60.5 | 66.7 | ||||

| Radiology | 41.4 | 75.0 | 87.5 | 60.0 | 84.6 | 92.9 | 21.4 | 63.6 | 77.3 | |||||||||

| Clinical oncology | 27.3 | 65.0 | 67.9 | 27.3 | 66.7 | 70.6 | 27.3 | 62.5 | 63.6 | |||||||||

| Pathology | 50.0 | 78.5 | * | 85.6 | * | 57.4 | 83.7 | 86.0 | 38.7 | 70.0 | 84.8 | * | ||||||

| Psychiatry | 57.3 | ** | 72.5 | 81.9 | 59.5 | 84.6 | 88.6 | 55.0 | ** | 61.0 | 76.0 | |||||||

| Other medical specialties | 11.8 | ** | 20.3 | ** | 25.5 | ** | 6.2 | ** | 9.4 | ** | 22.9 | ** | 21.4 | 31.2 | * | 27.8 | ** | |

| TOTAL | 50.3 | 70.0 | 78.1 | 52.7 | 74.6 | 83.1 | 45.8 | 61.6 | 68.9 |

Notes: The percentages represent concordance within each broad group. Thus, for example, within the hospital medical specialties, if a doctor chose (say) general medicine in year one and practised in cardiology in year 27, the choices count as a ‘match’. The percentages for specialist practice, overall, represent those for the doctors whose original choice and eventual destination were within the same broad specialty group. Numbers include tied and untied first choices for each specialty mainstream. Accident and emergency medicine, community health and public health medicine have been included under ‘Other medical specialties’. Non-medical choices have been excluded. For comparisons of percentages within specialist practice

indicates p<0.01

indicates p<0.001 for the significance of differences from the overall percentage.

A significantly higher percentage of men than of women were working in year 27 in the specialty group that they had originally chosen as junior doctors (χ21= 51.6, 32.1, 8.8 for Years 5, 3, 1 respectively; p<0.001, p<0.001, p=0.003 respectively).

Differences were evident between mainstream specialties in the degree to which early choice was related to later career destination (Table 4). Early choices for general practice were more highly predictive of later specialty destination than were choices for specialist practice combined (χ21 values gave p=0.02, p<0.001, p<0.001 respectively for Years 5, 3 and 1). Within specialist practice, differences by specialty were statistically significant both overall and separately for men and women in each of the three years (p<0.001 for χ29 test in each case). Analysis of standardised residuals show which specialties, within hospital practice, were significantly different from the rest (Table 4).

Satisfaction with job

NHS respondents rated their job satisfaction highly with an overall median score of 19.5 on a scale from 5 (very low satisfaction) to 25 (very high satisfaction) (Table 5). Job satisfaction was rated a little more highly by those in UK medicine outside the NHS (21.2) and those in medicine outside the UK (21.0), both comparisons with NHS doctors (p<0.001).

Table 5.

Job satisfaction and satisfaction with time available for leisure of the medically employed respondents from the cohort of UK qualifiers of 1977; grouped median scores for job satisfaction from 5 (not at all satisfied) to 25 (extremely satisfied) and grouped median scores for satisfaction with time available for leisure from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 10 (extremely satisfied)

| Job satisfaction score | Leisure satisfaction score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Total | Men | Women | Total | |

| All in the NHS | 20 | 20 | 20 | 4.3 | 5.4 | 4.6 |

| General practice | 19 | 20 | 19 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 4.9 |

| Hospital practice | 20 | 20 | 20 | 4.1 | 5.2 | 4.3 |

| Specialist practice: | ||||||

| Hospital medical specialties | 20 | 20 | 20 | 4.0 | 5.6 | 4.3 |

| Surgical specialties | 20 | 20 | 20 | 3.7 | 6.3 | 3.8 |

| Paediatrics | 21 | 20 | 20 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 3.6 |

| Accident & emergency | 20 | 21 | 20 | 3.8 | 5.3 | 4.3 |

| Obstetrics & gynaecology | 20 | 20 | 20 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 4.1 |

| Anaesthetics | 19 | 20 | 19 | 4.8 | 5.9 | 5.1 |

| Radiology | 19 | 20 | 19 | 4.6 | 3.8 | 4.4 |

| Clinical oncology | 20 | 20 | 20 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 3.4 |

| Pathology | 20 | 19 | 19 | 5.2 | 6.4 | 5.7 |

| Psychiatry | 18 | 19 | 19 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| Community health | 17 | 20 | 20 | 4.0 | 6.4 | 6.2 |

| Public health medicine | 20 | 20 | 20 | 5.5 | 3.7 | 4.4 |

| Full-time general practice | 19 | 19 | 19 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.4 |

| Part-time general practice | 20 | 20 | 20 | 6.3 | 6.9 | 6.7 |

| Full-time hospital practice | 20 | 20 | 20 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Part-time hospital practice | 19 | 20 | 20 | 5.5 | 6.7 | 6.4 |

| UK, medical jobs, outside NHS | 21 | 21 | 21 | 7.0 | 7.7 | 7.3 |

| Medicine abroad | 21 | 21 | 21 | 6.2 | 7.1 | 6.4 |

| General practice | 19 | 21 | 20 | 5.0 | 7.5 | 6.4 |

| Hospital practice | 21 | 21 | 21 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 6.5 |

Job satisfaction scores: 2106/2118 (99.4%) of respondents in medical employment gave valid replies. Leisure satisfaction scores: 2107/2118 (99.5%) of respondents in medical employment gave valid replies.

Among NHS respondents, the overall median scores for men and women were very similar (p=0.2), as were those for part-time and full-time doctors (p=0.6). Hospital doctors were slightly more satisfied (median 19.7) than GPs (19.3, p=0.006). The difference between hospital doctors and GPs in this respect was more apparent among full-time doctors (p=0.001) than among part-time doctors (p=0.4), and more apparent among men (p=0.002) than among women (p=0.6).

Satisfaction with time available for leisure

The scores of NHS doctors for satisfaction with time available for leisure activities were distributed bi-modally and were low with a median score of 4.6, on a scale from 1 (very low) to 10 (very high). NHS doctors were significantly less satisfied than those in UK medicine outside the NHS (7.3) and those in medicine outside the UK (6.4) (both comparisons p<0.001).

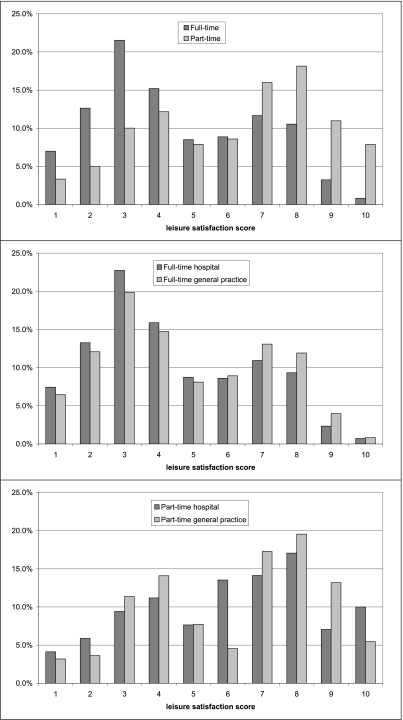

Within the NHS, part-time doctors were much more satisfied with their leisure time (Table 5, median score 6.6, and Figure 1) than were full-time doctors (4.1, p<0.001). Full-time GPs were more satisfied (4.4) than full-time hospital doctors (3.9, p=0.01). Within the group of full-time hospital doctors, the scores for men and women were the same (3.9); and, similarly, within the group of full-time GPs, the median scores for men and women were the same (4.4). Among women part-timers, GPs had a similar level of satisfaction (6.9) to part-time women hospital doctors (6.8, p=0.7). Among male part-timers, GPs appeared more satisfied (6.3) than hospital doctors (5.3) but numbers were small and the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.4). Figure 1 illustrates how levels of satisfaction with leisure time varied for full-time and part-time hospital doctors and GPs working in the NHS.

Figure 1.

Leisure satisfaction scores for NHS doctors: full-timers, part-timers; and hospital doctors, GPs

Views of respondents about their jobs and careers

Table 6 shows responses to attitude statements about working conditions, support and careers for NHS doctors. For ease of presentation, the categories strongly agree and agree, and strongly disagree and disagree have been aggregated and presented under the headings ‘agree’ and ‘disagree’.

Table 6.

Views of respondents about their jobs and careers for doctors working in the NHS. Values are percentages

| Men (n=1251) | Women (n=637) | All (n=1888) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude statement | Agree | Neither | Disagree | Agree | Neither | Disagree | Agree | Neither | Disagree |

| Working conditions and support: In my current post . . . | |||||||||

| I receive good support from nursing staff | 77.7 | 11.7 | 10.5 | 81.1 | 12.3 | 6.6 | 78.9 | 11.9 | 9.2 |

| I receive good support from hospital/practice management | 45.8 | 21.1 | 33.1 | 44.0 | 24.3 | 31.7 | 45.2 | 22.1 | 32.6 |

| I work longer hours than I think I should | 69.1 | 16.3 | 14.6 | 63.7 | 15.2 | 21.1 | 67.3 | 15.9 | 16.8 |

| The working conditions (e.g. resources, environment) are satisfactory | 39.4 | 17.5 | 43.1 | 41.8 | 16.5 | 41.7 | 40.2 | 17.2 | 42.6 |

| Your career: | |||||||||

| I have had good career opportunities in my career to date | 71.3 | 19.8 | 8.9 | 64.3 | 21.2 | 14.5 | 69.0 | 20.3 | 10.8 |

| I have had good opportunities for continuing education and career development | 66.3 | 19.8 | 13.9 | 63.8 | 17.9 | 18.3 | 65.4 | 19.2 | 15.4 |

| There are good prospects for improvement of the NHS in my specialty as a whole | 41.3 | 25.8 | 32.9 | 35.2 | 27.8 | 37.0 | 39.3 | 26.5 | 34.2 |

Men's and women's views about working conditions and support did not differ greatly. More respondents agreed that the nursing staff were supportive (78.9% overall) than agreed that management was supportive (45.2%). 67.3% agreed that their working hours were excessive and only 40.2% of respondents considered that their working conditions (e.g. resources available, environment) were satisfactory.

Overall, 69.0% agreed that they had had good career opportunities to date and 65.4% were positive about opportunities for career development. 39.3% agreed that the prospects for improvement of the NHS in their specialty as a whole were good while 34.2% disagreed. Differences between men and women on these statements were small.

Discussion

Principal findings

Our paper provides unique information about senior NHS doctors' career destinations and levels of job satisfaction. For example, 27 years after qualification, the percentage of women who were working in the NHS was very similar to that of men. The doctors had high levels of satisfaction with the content of their jobs, but they were not so satisfied with their working hours and working conditions.

Strengths and weaknesses of study

This is, we believe, the most comprehensive study ever undertaken of a cohort of UK doctors who qualified in the 1970s. It also covers the longest period after qualification that has been studied by our group. Our findings, particularly those using capture-recapture, provide the most comprehensive and precise estimates available on the participation of a cohort from this generation in the NHS. It updates our findings on this cohort when surveyed in 1995.7

A limitation of our study is that, although the response rates are high for this kind of survey, responder bias needs to be considered. It is evident from the comparison of Tables 1 and 2 that we achieved a higher response rate from those working in the NHS than from others. We are confident that, when the capture-recapture analysis is included, our estimates of NHS participation are accurate. We cannot be so sure about the distribution of the others, notably about the estimates for those working in medicine outside the NHS compared with those not in medicine. Our findings from responders suggest that, of those not in the NHS, a considerably higher proportion is in medicine outside the NHS than are not in medicine at all. This corresponds with evidence from other surveys that, if doctors leave the NHS, they are much more likely to continue to practise medicine (in the UK, outside the NHS, and abroad) than to leave the profession.10

Policy implications

In addition to documenting the careers of the cohort itself, our results provide findings on career pathways and job satisfaction that could be compared, in future, with the career pathways and satisfaction of later generations of doctors. For example, we have shown that almost four-fifths of the cohort of 1977 who chose general practice in year 3 (roughly the stage at which young doctors now are being encouraged to make their specialty choice in the UK) were working in it 25 years later. In hospital specialist practice, about two-thirds of the cohort who chose a hospital specialty group was working in it eventually. Thus, while in many cases the doctors made early choices that were later sustained, a sizeable minority of doctors followed different paths to their choice in their early years. This is relevant to current debate in the UK about whether the new postgraduate training scheme, Modernising Medical Careers, will provide enough flexibility to accommodate a degree of uncertainty among junior doctors about the careers that they will eventually want to follow.

The percentage of women who eventually practised medicine in the NHS was fractionally smaller than that of men; but the similarities between men and women in this respect are much more striking than the differences. This should allay concerns sometimes expressed about increasing the intake of women to medical school, that many more women than men might give up practice. They do not; and, when they do for family reasons, they generally return to medical work.7 However, almost half of all women in the cohort – typically now in their early 50s – practised part-time. Clearly, workforce planning needs to take this into account.

Future research

The NHS doctors rated their job satisfaction reasonably highly, but satisfaction with time available for leisure was often fairly low. Dissatisfaction among senior doctors may have important implications because it could provide motivation for them to reduce their working hours substantially and/or retire early.11–13 It is also possible that, although the great majority of these doctors are in very senior and distinguished posts, some have further ambitions for the development of their careers. We explore their future plans in the next paper.

Another possible area for future research would focus on the fact that a higher percentage of women than men in hospital practice are not at consultant level. We do not know whether this is by choice or whether some women feel disadvantaged in this respect. This should be a topic for further study, particularly of younger generations.

Not surprisingly, a higher percentage of women than men entered general practice; but the difference, in this generation, is not great. The gap has widened substantially since then: in recent cohorts, about double the percentage of women than men expect to enter general practice.8 A much higher percentage of men than women entered the surgical specialities: in recent cohorts the gap is narrowing but it is still very wide.9 The current reasons for the gap between men and women in specialty choice warrant more detailed investigation.

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS —

Competing interests None declared

Funding The UK Medical Careers Research Group is funded by the UK Department of Health. The Unit of Health Care Epidemiology is funded by the NHS National Centre for Research Capacity Development

Ethical approval This study was approved by the Central Office for Research Ethics Committees (COREC), REC 04/Q1907/48

Guarantor KT

Contributorship All authors contributed equally

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to each doctor who participated. We thank Janet Justice and Alison Stockfordfor their careful data entry, and Emma Ayres for survey administration

Appendix A: Calculation of satisfaction scores

A1. Job satisfaction score

The questionnaire included the following five statements:

| Statement | Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neither | Disagree | Strongly disagree | ||

| 1. | I find enjoyment in my current employment | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 2. | I am doing interesting and challenging work | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 3. | I feel dissatisfied with my current employment | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4. | Most days I am enthusiastic about my work | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 5. | I am often bored with my work | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Recipients were asked to score all five statements. A job satisfaction score in the range 5–25 was calculated by aggregating the scores for the five statements.

A2. Leisure satisfaction score

The questionnaire included the question: ‘How satisfied are you with the amount of time your work leaves you for family, social and recreational activities?’. Respondents were asked to score their answer on a scale from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 10 (extremely satisfied).

Appendix B: Calculations undertaken to construct the ‘hypothetical cohort’ of 100 qualifiers for Table 2

All in the NHS

These percentages were calculated by capture-recapture analysis. Details of this method are given elsewhere6. This provided the most reliable whole-cohort estimate of NHS participation (76.1%) by maximising the use of all available information.

Specialty groups within the NHS

The percentages from the survey were scaled in order to redistribute the percentage in the NHS (76.1%, given by the capture-recapture analysis) according to the distribution of the specialty groups within the NHS (as provided by survey responders, Table 1).

Deceased

All deaths known to us have been included, without scaling.

Employed in medicine outside the NHS, and not employed in medicine

After allowing for those in the NHS and those known to have died, 22 doctors per 100 qualifiers remained. We distributed the remainder – doctors in the UK in medical practice, outside the NHS, those in medicine overseas and those not in medical employment – according to the distribution of these three groups in the responder population.

References

- 1.Taylor K, Lambert T, Goldacre M. Future plans of a cohort of senior doctors working in the National Health Service. JRSM. 2008;101:182–90. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.2007.070276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkhouse J. Doctors' careers: aims and experiences of medical graduates. London: Routledge; 1991. (Out of print; copies available on request from the authors) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Royal Commission on Medical Education 1965-8. Report. London: HMSO; 2001. 1968 (Cmnd 3569) (Todd Report) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert T, Goldacre M, Davidson J, Parkhouse J. Loss of British-trained doctors from the medical workforce in Great Britain. Med Educ. 2001;35:337–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2001.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hook EB, Regal RR. The value of capture-recapture methods even for apparent exhaustive surveys. Amer J Epid. 1992;135:1060–7. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambert T, Goldacre M, Davidson J, Parkhouse J. Estimation of numbers of British medical graduates working in the National Health Service: comparison of capture-recapture analysis and exhaustive tracing. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2004;9:234–6. doi: 10.1258/1355819042250212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson JM, Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ. Career pathways and destinations 18 years on among doctors who qualified in the United Kingdom in 1977: postal questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998;317:1425–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7170.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Turner G. Career choices of the United Kingdom medical graduates of 2002: questionnaire survey. Medical Education. 2006;40:517–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Turner G. Career choices of United Kingdom medical graduates of 1999 and 2000: questionnaire surveys. BMJ. 2003;326:194–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss P, Lambert TW, Goldacre MJ, Lee P. Reasons for considering leaving UK medicine: questionnaire study of junior doctors' comments. BMJ. 2004;329:1263–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38247.594769.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luce A, van Zwanenberg T, Firth-Cozens J, Tinwell C. What might encourage later retirement among general practitioners? J Manag Med. 2002;16:303–10. doi: 10.1108/02689230210445112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sibbald B, Bojke C, Gravelle H, Tinwell C. National survey of job satisfaction and retirement intentions among general practitioners in England. BMJ. 2003;326:22–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7379.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.French FH, Andrew JE, Awramenko M, et al. Consultants in NHS Scotland: a survey of work commitments, remuneration, job satisfaction and retirement plans. Scott Med J. 2004;49:47–52. doi: 10.1177/003693300404900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]