Abstract

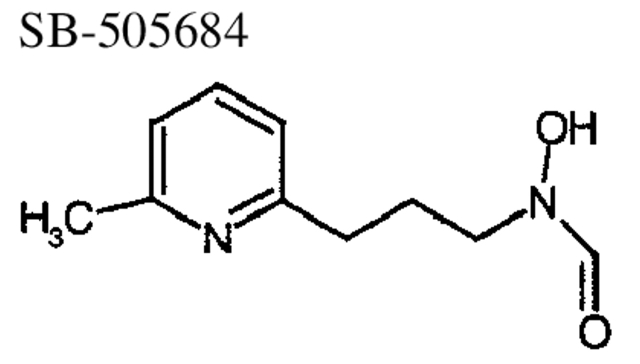

Polypeptide deformylase (PDF) catalyzes the deformylation of polypeptide chains in bacteria. It is essential for bacterial cell viability and is a potential antibacterial drug target. Here, we report the crystal structures of polypeptide deformylase from four different species of bacteria: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and Escherichia coli. Comparison of these four structures reveals significant overall differences between the two Gram-negative species (E. coli and H. influenzae) and the two Gram-positive species (S. pneumoniae and S. aureus). Despite these differences and low overall sequence identity, the S1′ pocket of PDF is well conserved among the four enzymes studied. We also describe the binding of nonpeptidic inhibitor molecules SB-485345, SB-543668, and SB-505684 to both S. pneumoniae and E. coli PDF. Comparison of these structures shows similar binding interactions with both Gram-negative and Gram-positive species. Understanding the similarities and subtle differences in active site structure between species will help to design broad-spectrum polypeptide deformylase inhibitor molecules.

Keywords: PDF, deformylase, crystal structure, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae

Newly synthesized polypeptide chains in prokaryotes carry a transiently formylated N terminus (Marcker and Sanger 1964; Adams and Capecchi 1996; Webster et al. 1996). The metalloprotease polypeptide deformylase (PDF) deformylates the N-formylmethionine group prior to removal of the N-terminal methionine by methionine aminopeptidase (Adams 1968; Takeda and Webster 1968; Livingston and Leder 1969. For review, see Pei 2001). Removal of the N-terminal methionine residue from polypeptide chains is thought to be important for biological activity and correct posttranslational modification and is strictly dependent on the removal of the N-formyl group by PDF. PDF has been cloned from a number of different species of bacteria and has been shown to be essential for bacterial cell viability (Mazel et al. 1994; Margolis et al. 2000). PDF is believed to exist in vivo as the Fe2+ form, although oxidation of Fe2+ by atmospheric oxygen renders Fe-PDF very unstable, making active PDF notoriously difficult to purify. This has been overcome by the use of oxygen scavengers (e.g., TCEP or catalase) during purification or by replacement of the bound iron by other divalent metal cations that are less sensitive to oxidation (Meinnel and Blanquet 1995; Rajagopalan et al. 1997, 2000; Groche et al. 1998; Ragusa et al. 1998). The Fe2+ has been successfully replaced by metal ions such as Ni2+, Zn2+, and Co2+, and, except in the case of Zn-PDF, which has a 500-fold lower enzymatic activity, the catalytic activities of different metalloforms of PDF have been shown to be essentially identical. Recently, a eukaryotic homolog of polypeptide deformylase has been cloned (Giglione et al. 2000), and data from genome sequencing has revealed PDF-like sequences in eukaryotic genomes. However, the exact function of deformylase in eukaryotes has yet to be determined.

The three-dimensional structure of E. coli PDF has been determined by X-ray crystallography (Chan et al. 1997; Becker et al. 1998a,b; Hao et al. 1999; Clements et al. 2001) and NMR (Dardel et al. 1998; O’Connell et al. 1999). More recently, the structure of PDF from Plasmodium falciparium, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Bacillus stearothermophilus have also been determined (Baldwin et al. 2002; Guilloteau et al. 2002; Kumar et al. 2002). These structures show that PDF adopts a fold unlike that of other metalloproteases. In particular, PDF is unique as it lacks the non-prime side usually found in other metalloproteases. The metal-binding site, however, is most similar to thermolysin, with both enzymes ligating the bound metal with two histidines from a conserved HEXXH motif. Crystal structures of Fe, Ni, Zn, and Co forms of E. coli PDF have been determined and have been shown to be essentially identical, with the metal tetrahedrally coordinated by a water molecule, two histidines (from the conserved HEXXH motif), and a cysteine. In addition, site-directed mutagenesis has shown that a conserved glutamate and glutamine residue in the active site are essential for catalytic activity (Meinnel et al. 1995, 1997; Rajagopalan et al. 2000). The structure of E. coli PDF complexed with the reaction product Met–Ala–Ser, and inhibitors BB-3497 and actinonin show how the S1′ pocket can accommodate hydrophobic side chains, and the lack of a non-prime side explains the preference of the enzyme for N-formyl and N-acetylated substrates (Becker at al. 1998a; Hao et al. 1999; Clements et al. 2001). These structures also reveal how the putative catalytic water molecule, which normally coordinates the metal in unliganded structures, can be displaced by the carbonyl group of an inhibitor molecule.

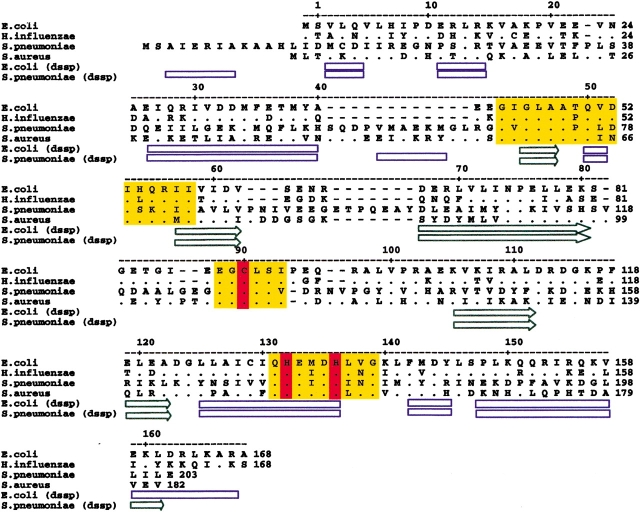

Based on sequence homology, PDFs are typically classified as type I or II. In this paper, we describe the crystal structures of PDF from four different bacterial species: two Gram-positive species (type II PDF), S. pneumoniae and S. aureus, and two Gram-negative species (type I PDF), H. influenzae and E. coli. The sequence identity between the Gram-negative and Gram-positive species of PDF is very low (e.g., there is 31% sequence identity between H. influenzae and S. pneumoniae PDF calculated between residues 1–162 of H. influenzae PDF; see structure-based sequence alignment in Fig. 1 ▶), whereas the sequence identity between the different Gram-positive species or different Gram-negative species is high (e.g., E. coli and H. influenzae PDF show 65% sequence identity, calculated between residues 1–168; see Fig. 1 ▶). The area of high sequence identity across both Gram-negative and Gram-positive species of PDF is restricted to the active site of the enzyme (yellow areas in Fig. 1 ▶). We show that the tertiary structure of the deformylase active site is conserved between S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, H. influenzae, and E. coli despite significant structural differences elsewhere in the protein. In addition, we have determined the structure of three nonpeptidic reversed hydroxymate inhibitors, SB-485345, SB-543668, and SB-505684, in complex with S. pneumoniae and E. coli PDF, and compare the binding of these inhibitors to the two species of PDF.

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of E. coli, H. influenzae, S. aureus, and S. pneumoniae PDF. Structure-based sequence alignment of E. coli, H. influenzae, S. aureus, and S. pneumoniae PDF. Secondary structure assignments for E. coli and S. pneumoniae PDF were carried out using DSSP (Kabsch and Sander 1983). α-Helical regions are shown as blue rectangles, and β-sheet regions are shown as green arrows. Insertions are shown as dashes (—). Residues that are identical between E. coli and H. influenzae PDF are shown in the H. influenzae sequence as a dot (•). Residues that are identical between S. aureus and S. pneumoniae PDF are shown in the S. aureus sequence as a dot (•). Residues that are identical across the four species are also shown as a dot (•) in the S. pneumoniae PDF sequence. Areas of sequence identity across the four species of PDF are highlighted in yellow. His 132, His 136, and Cys 90, which coordinate the bound nickel, are highlighted in red.

Results

Enzyme activities

The PDF proteins used for structure determination were expressed and purified as described in Materials and Methods; PDF purified in the presence of nickel was used for all enzymatic and structural work. The catalytic properties of PDF enzymes from E. coli, H. influenzae, S. aureus, and S. pneumoniae toward the peptide substrate fMAS were assessed at pH 7.6 using a formate dehydrogenase coupling reaction. The Km, kcat, and second-order rate constant kcat/Km for the four enzymes are listed in Table 1. All the enzymes showed saturation kinetics. The high Km values indicate that the enzymes have relatively low affinity for the peptide fMAS. However, the kcat/Km values obtained indicate that PDF is a rather robust catalyst.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of PDF enzymes

| Km (mM) | Kcat sec−1 | Kcat/Km M−1 • sec−1 | |

| E. coli | 9.1 | 103 | 0.11 × 105 |

| H. influenzae | 4.8 | 322 | 0.67 × 105 |

| S. aureus | 2.6 | 152 | 0.58 × 105 |

| S. pneumoniae | 4.0 | 332 | 0.83 × 105 |

Overall structure of S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, E. coli, and H. influenzae polypeptide deformylase

The structures of PDF from four different species of bacteria, S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, E. coli, and H. influenzae were determined by X-ray crystallography (crystallographic statistics in Tables 2 , 3). The crystal structure of S. pneumoniae PDF was determined to 2.0 Å by MAD using selenomethionine-labeled protein (Materials and Methods; Table 3). This facilitated the structure determination of S. aureus PDF by molecular replacement. The structure of H. influenzae PDF was determined by molecular replacement, using published E. coli PDF coordinates as a search model. Comparison of the crystal structures of the four different species of PDF shows significant overall structural difference between the Gram-negative and Gram-positive forms of the enzyme.

Table 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| E. coli | S. pneumoniae | S. aureus | H. influenzae | |||||

| Species Inhibitor | 485345 | 543668 | 505684 | 485345 | 543668 | 505684 | Apo | 107991a |

| Space group | C2 | C2 | C2 | P4(3) | P4(3) | P4(3) | 14 | P2(1) |

| Mols. ASU | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Unit cell | ||||||||

| a (Å) | 139.178 | 139.182 | 141.825 | 49.889 | 49.701 | 49.672 | 167.300 | 45.947 |

| b (Å) | 63.350 | 63.241 | 64.045 | 49.889 | 49.701 | 49.672 | 167.300 | 87.948 |

| c (Å) | 85.672 | 85.573 | 83.738 | 91.565 | 91.835 | 92.161 | 42.250 | 98.183 |

| β (°) | 121.23 | 121.48 | 123.31 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 90.0 | 90.95 |

| Resolution (Å) | 20–1.7 | 20–1.5 | 20–1.7 | 20–2.0 | 20–1.7 | 20–1.7 | 20.0–2.5 | 20–2.5 |

| (last shell) | (1.72–1.70) | (1.54–1.50) | (1.72–1.70) | (2.05–2.0) | (1.72–1.70) | (1.72–1.70) | (2.54–2.50) | (2.54–2.50) |

| Redundancy | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 3.6 |

| I/σ (last shell) | 20.3 (4.6) | 19.9 (3.5) | 20.3 (3.8) | 20.9 (2.5) | 31.1 (6.8) | 29.1 (3.7) | 21.7 (6.5) | 23.4 (4.1) |

| Completeness | 97.7 (96.6) | 95.8 (80.4) | 97.1 (91.0) | 98.6 (98.3) | 99.5 (99.9) | 97.1 (91.0) | 89.3 (82.5) | 99.8 (99.4) |

| (last shell) (%) | ||||||||

| Rsym (%)b | 5.2 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 5.6 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 6.2 |

| (last shell) (%) | (17.2) | (37.3) | (33.5) | (22.8) | (19.2) | (33.5) | (12.8) | (29.2) |

| Rcryst (%)c | 21.2 | 20.8 | 20.62 | 22.0 | 23.5 | 22.7 | 22.1 | 21.2 |

| Rfree (%)d | 22.6 | 22.6 | 22.7 | 26.3 | 25.8 | 25.8 | 27.2 | 28.2 |

| RMSd | ||||||||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.0042 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 0.0055 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.0064 |

| Angles (°) | 1.139 | 1.152 | 1.152 | 1.149 | 1.152 | 1.153 | 1.345 | 1.274 |

| Protein atoms | 3964 | 3964 | 3964 | 1519 | 1502 | 1513 | 2861 | 5244 |

| Solvent molecules | 493 | 552 | 597 | 187 | 211 | 232 | 265 | 241 |

The S. pneumoniae/SB-485345 data set used for final refinement was collected on an in house Raxis 4 detector with Yale mirrors/Rigaku generator. The S. aureus/native data were collected at Daresbury on station 9.6. All other data sets were collected at the ESRF on ID 14.2.

a This inhibitor is an SKF molecule, all other inhibitors are SB molecules.

bRsym = Σ |Ii− <I>|/ΣIi, where Ii is the intensity of the ith observation of a reflection and <I> is the mean intensity of the reflection.

cRcryst = Σ||Fobs| − |Fcal||/Σ|Fobs|, where |Fobs| and |Fcal| are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes for a reflection.

dRfree was calculated from a disjoint set of reflections excluded from the refinement stages (5% for E. coli/SB-485345 and H. influenzae/SKF-107991 and 10% for all other structures).

Table 3.

Selenomethionine MAD data collection statistics

| SeMet MAD | |||

| λ1 (peak) | λ2 (edge) | λ3 (remote) | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.979192 | 0.979349 | 0.8856 |

| Resolution (Å) | 30–2.0 | 30.0–2.0 | 30.0–2.0 |

| (highest shell) | (2.05–2.00) | (2.05–2.00) | (2.05–2.00) |

| Redundancy | 2.4 | 2.4 | 2.1 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.982 | 0.963 | 1.098 |

| Completeness (%) | 87.7 | 86.5 | 80.8 |

| (highest shell) | (92.6) | (89.9) | (62.2) |

| Rsym (%)a | 4.6 | 4.0 | 4.2 |

| (highest shell) | (29.1) | (18.0) | (29.0) |

The S. pneumoniae/SB-485345 selenomethionine MAD data set was collected at the ESRF on BM14.

aRsym = Σ |Ii− <I>|/ΣIi, where Ii is the intensity of the ith observation of a reflection and <I> is the mean intensity of the reflection.

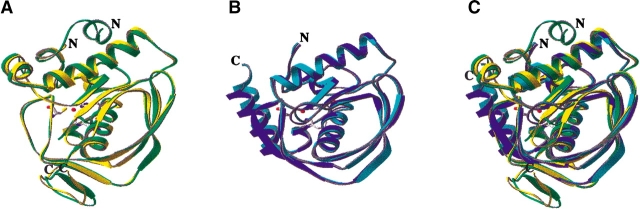

The overall structures of the two Gram-negative species of PDF (E. coli and H. influenzae) are very similar, with an RMSD of 1.15 Å on all Cα atoms (Fig. 2A ▶). The structures of the two Gram-positive species of PDF (S. aureus and S. pneumoniae) are also very similar, with an RMSD of 0.68 Å on Cα atoms 13–202 of S. pneumoniae PDF (Fig. 2B ▶). However, there are significant overall differences between the Gram-negative and Gram-positive species of PDF (Fig. 2C ▶). The Gram-positive PDF enzymes are both larger in size than the Gram-negative enzymes. This size difference is manifested by structural differences at both the N and C termini of the proteins and by insertions in the proteins of S. pneumoniae and S. aureus PDF (Figs. 1 ▶, 2 ▶). The structure of the C termini of S. pneumoniae and S. aureus PDF is very different from that of E. coli and H. influenzae PDF. The C terminus of E. coli and H. influenzae PDF is helical. In contrast, the C terminus of S. pneumoniae and S. aureus PDF is not helical, but folds over the enzyme and forms an antiparallel β-sheet with residues 119–123, completing a three-stranded β-sheet in Gram-positive species of PDF. At the N terminus of PDF, both the S. aureus and S. pneumoniae proteins are extended relative to the E. coli and H. influenzae proteins. Specifically, in S. pneumoniae PDF, the N terminus begins with two turns of an α-helix that subsequently leads into an extended strand. The N terminus of S. aureus PDF is somewhat shorter and lacks the initial helical region observed in the S. pneumoniae structure.

Figure 2.

Crystal structures of E. coli, H. influenzae, S. aureus, and S. pneumoniae PDF. Comparison of the crystal structure of PDF from E. coli (cyan), H. influenzae (dark blue), S. pneumoniae (green), and S. aureus (yellow). (A) S. pneumoniae and S. aureus PDF. (B) E. coli and H. influenzae PDF. (C) All four species of PDF. The bound nickel is in red, and His 132, His 136, and Cys 90 are shown as a ball-and-stick representation. S. pneumoniae PDF is 13 residues longer at the N terminus than S. aureus PDF. The major difference between PDF from E. coli and from H. influenzae is the angle of the C-terminal α-helix. This is mainly due to the presence of bulky Phe 96 in H. influenzae PDF (Q in E. coli PDF), which packs against the C-terminal α-helix. The figure was made using RIBBONS (Carson 1991).

In addition to the differences in structure at the N and C termini of the different species of PDF, there are two insertions in the Gram-positive enzymes relative to the Gram-negative proteins. For S. pneumoniae and S. aureus PDF, there is a 12-residue insertion between residues 55 and 66 (S. pneumoniae numbering; Fig. 1 ▶), where the protein forms two turns of an α-helix. S. pneumoniae PDF, the largest of all four species studied, also has a 7-residue insertion between residues 96 and 102.

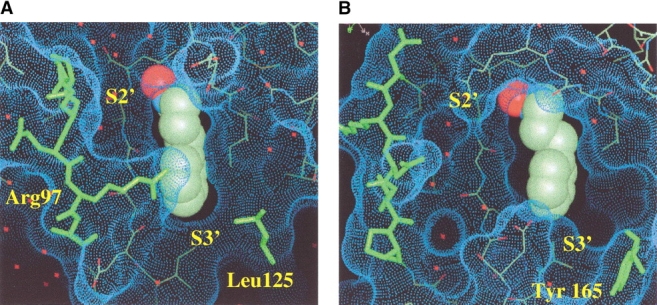

The active site of S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, and H. influenzae polypeptide deformylase

The substrate-binding site of PDF can be divided into three main areas, the S1′, S2′, and S3′ pockets (Fig. 3 ▶) and the metal-binding site. The S1′ pocket is a hydrophobic pocket, whereas the S2′ and S3′ pockets are shallow, less well-defined, surface depressions. In the four structures described here the bound metal is nickel and is coordinated by two histidines residues and one cysteine residue from the protein (Fig. 1 ▶). Metal coordination has previously been described in detail for E. coli PDF (Becker et al. 1998a). Despite the structural differences between the Gram-positive and Gram-negative forms of PDF, the S1′ pocket in all four species is remarkably similar. The shape, size, and charge of the S1′ pocket is almost identical between species, although the width of the pocket is ∼1.4 Å wider in the case of S. aureus and S. pneumoniae PDF (measured from residues 44–89 in E. coli PDF and 70–128 in S. pneumoniae PDF; Fig. 3B ▶). The main difference in the structure of the S1′ pocket occurs at the entrance to the pocket (S1′/S3′ boundary), residue 125 in E. coli, and residue 165 in S. pneumoniae, where a nonconservative amino acid substitution is observed (Fig. 3 ▶). In E. coli and H. influenzae PDF, a leucine is observed at this position, whereas in S. aureus and S. pneumoniae PDF, this residue is a tyrosine. This nonconservative difference alters both the accessibility and charge at the solvent-exposed face of the S1′ pocket and could account for subtle specificity differences between the Gram-negative and Gram-positive species of PDF.

Figure 3.

Active site of PDF E. coli/SB-485345 and PDF S. pneumoniae/SB-485345. The active sites of PDF E. coli/SB-485345 (A) and PDF S. pneumoniae/SB-485345 (B). The solvent-accessible surfaces (calculated in QUANTA using a 1.4-Å probe with the water molecules and inhibitors removed) are shown in the figure as blue dots. The inhibitor molecules are shown in a space-filling representation. Residues 92–100 in E. coli PDF and 131–140 in S. pneumoniae PDF are shown in green. Tyr 165 in S. pneumoniae PDF and Leu 125 in E. coli PDF are also marked on the figure in green. Note that Tyr 165 in S. pneumoniae PDF adopts a different rotamer conformation in the structures S. pneumoniae PDF/SB-543668 (Fig. 5D ▶) and S. pneumoniae PDF/SB-505684 (Fig. 5B ▶). The figure was prepared using QUANTA. The S2′ and S3′ pockets are labeled on the figure; the aromatic ring of the inhibitor is bound in the S1′ pocket.

Larger differences in structure are observed in the S2′ region of PDF between the four different species studied. The S2′ pocket is different between the Gram-negative and Gram-positive species of PDF owing to differences in sequence and length that occur in the strands 92–100 (E. coli and H. influenzae) and 131–140 (S. pneumoniae and S. aureus), which borders the S2′ pocket (Figs. 1 ▶, 3 ▶). In particular, in the E. coli and H. influenzae Gram-negative species of PDF, an arginine residue is observed at position 97, which is not observed in the Gram-positive S. pneumoniae and S. aureus species of PDF. Arg97 is solvent-exposed and is positioned at the S1′/S2′ boundary, with the potential to form hydrogen bonds to an inhibitor molecule bound in either the S1′ or S2′ pocket. The S3′ region is the less well-conserved part of the active site of PDF. There are significant differences in the S3′ region between the Gram-negative and Gram-positive species owing to a two-residue insertion (residues Gly 124 and Glu 125 in S. pneumonaie PDF; Fig. 1 ▶) at the S1′/S3′ boundary in the Gram-positive species (S. pneumoniae and S. aureus).

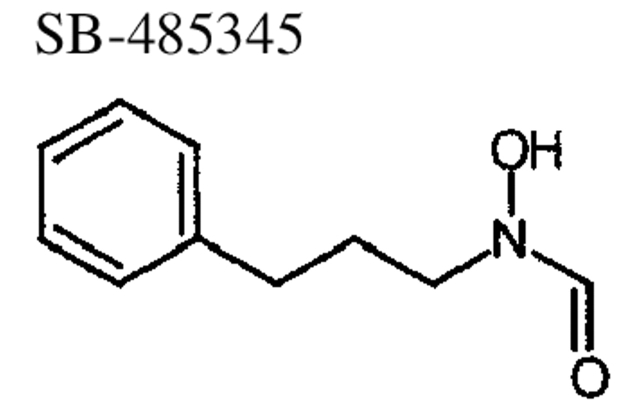

Inhibitor binding to E. coli and S. pneumoniae PDF

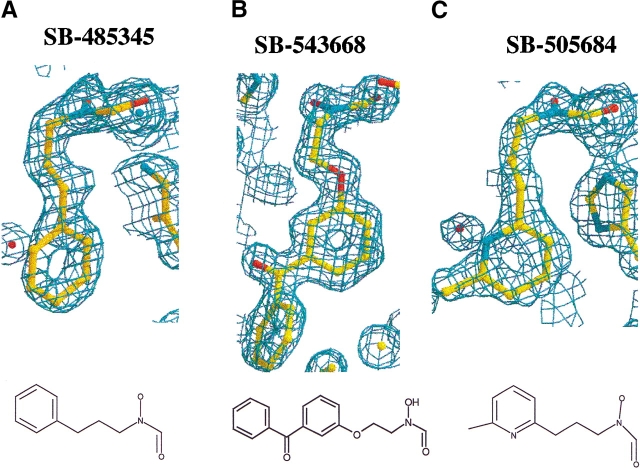

To investigate inhibitor binding to Gram-negative and Gram-positive species of PDF, the crystal structures of PDF from S. pneumoniae and E. coli were determined to 2.0 Å or better in the presence of three different reversed hydroxymate inhibitors, SB-485345, SB-543668, and SB-505684 (Fig. 4 ▶; Materials and Methods). The inhibitors are simple aromatic rings joined to a reversed hydroxymate group via a three-atom linker. SB-485345 is the simplest of the three inhibitors, whereas SB-543688 and SB-505684 have substitutions from the meta-position of the aromatic ring. Table 4 shows the IC50 values of the three inhibitor molecules for the four species of PDF studied.

Figure 4.

Electron density and chemical structure of SB-485345, SB-543668, and SB-505684. Electron density and chemical structure of SB-485345 (A), SB-543668 (B), and SB-505684 (C). The electron density shown is for the inhibitors bound to E. coli PDF. The electron density is from 2Fo − Fc maps contoured at 1.0 σ.

Table 4.

IC50s of compounds against S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, E. coli, and H. influenzae PDF

| IC50 (μM) | ||||

| S. aureus | E. coli | S. pneumoniae | H. influenzae | |

|

0.25 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.4 ± 0.04 | 0.15 ± 0.02 |

|

2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.15 ± 0.08 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 0.32 ± 0.01 |

|

1.09 ± 0.03 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 1.04 ± 0.05 |

Deformylation activities were measured in the presence of 10 nM of the respective enzymes and increasing concentrations of the compounds. The concentration of f-MAS was 2.5 mM (S. aureus), 9 mM (E. coli), and 4 mM (S. pueumoniae and H. influenzae).

For the three inhibitors, the reversed hydroxymate group coordinates the metal atom in a bidentate manner, with the carbonyl oxygen from the hydroxymate replacing the position usually occupied by a water molecule in unliganded structures (Becker et al. 1998a). The bound nickel has an unusual five-part coordination, similar to that which would be predicted in the catalytic mechanism of Becker et al. and previously observed in crystal structures of E. coli PDF/BB-3497 and E. coli PDF/actinonin (Clements et al. 2001). Although the inhibitor atoms coordinating the nickel are conserved, some small but significant variability is observed in the exact bond distances and angles of the hydroxymate moiety coordinating the nickel.

Binding of SB-485345 to E. coli and S. pneumoniae PDF

The crystal structure of SB-485345 in complex with E. coli and S. pneumoniae PDF shows that the same simple inhibitor molecule is bound in an almost identical manner to the two proteins (Fig. 3 ▶). In both proteins, the aromatic ring of SB-485345 binds in the hydrophobic S1′ pocket. The space-filling representation shows that the aromatic ring of SB-485345 fills most, but not all, of the available space in the S1′ pocket (Fig. 3 ▶). In particular, Figure 3B ▶ shows that the S1′ pocket of S. pneumoniae PDF is wider than the S1′ pocket of E. coli PDF (Fig. 3A ▶) such that SB-485345 fits more snugly into the S1′ pocket of E. coli PDF. The IC50s of SB-485345 for E. coli PDF (160 nM) and S. pneumoniae PDF (400 nM) are very similar (Table 4), with the 2.5-fold greater affinity of inhibitor for E. coli PDF consistent with the better fit in the S1′ pocket.

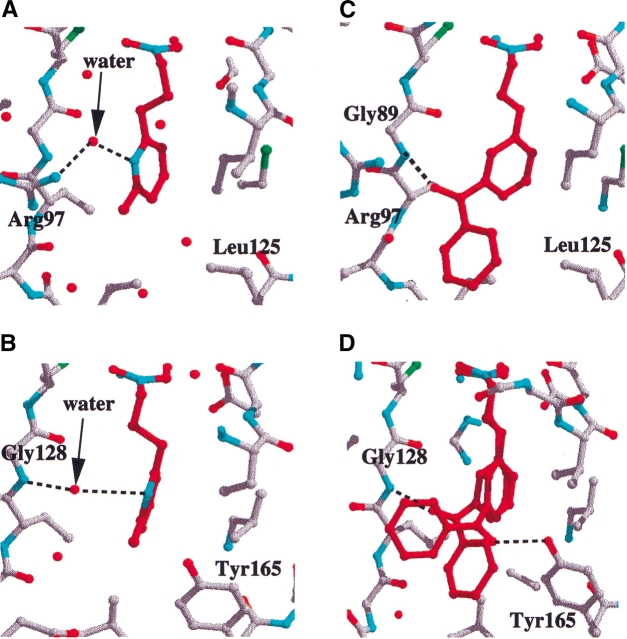

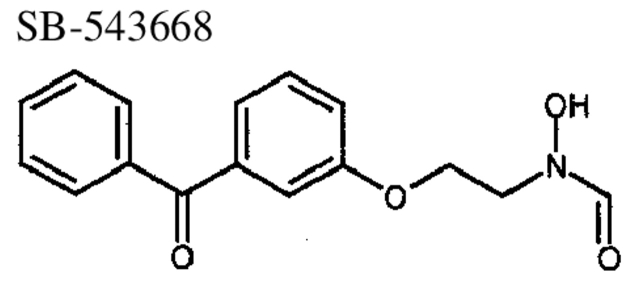

Binding of SB-505684 to E. coli and S. pneumoniae PDF

SB-505684 binds to E. coli and S. pneumoniae PDF slightly differently (Fig. 5A, B ▶). In E. coli PDF, the nitrogen from the pyridine ring hydrogen-bonds to arginine 97 via a water molecule (Fig. 5A ▶). In contrast, in S. pneumoniae PDF, the nitrogen of the pyridine ring hydrogen-bonds, via a water molecule, to the main-chain nitrogen of Gly 128 in the S1′ pocket (Fig. 5B ▶). The reason for the different binding modes is because the S1′ pocket is 1.4 Å wider (measured from residues 44 to 89 in E. coli PDF and 70 to 128 in S. pneumoniae PDF) in S. pneumoniae PDF than in E. coli PDF and therefore has room to accommodate both a water molecule and the pyridine group of the inhibitor molecule. In addition, the three-atom linker of the inhibitor molecule adopts a different conformation in both structures. Despite the difference in binding mode to E. coli and S. pneumoniae PDF, the affinity of SB-505684 is similar for the two species of PDF (Table 4).

Figure 5.

Binding of SB-543668 and SB-505684 to E. coli and S. pneumoniae PDF. SB-505684 binding to E. coli PDF (A) and S. pneumoniae PDF (B); SB-543668 binding to E. coli PDF (C) and S. pneumoniae PDF (D). Inhibitor molecules are colored in red, hydrogen bonds are marked as dashed lines, and water molecules are shown as red spheres. The figure was prepared with XTALVIEW (McRee 1993).

Binding of SB-543668 to E. coli and S. pneumoniae PDF

SB-543668 binds to E. coli PDF with the first aromatic ring in the S1′ pocket and the connecting carbonyl group hydrogen-bonding to the main-chain nitrogen of Gly 89 (Fig. 5C ▶). The meta-substituted aromatic group is mainly solvent accessible and directed toward the S3′ region. The electron density is very good for all of SB-543668 when bound to E. coli PDF (Fig. 4B ▶). In contrast, the electron density for SB-543668 binding to S. pneumoniae PDF indicates that there are two major binding modes (Fig. 5D ▶); one with the connecting carbonyl oxygen hydrogen-bonded to the main-chain nitrogen of Gly 128 and the second with the carbonyl oxygen hydrogen-bonded to the hydroxyl group of tyrosine 165 (a residue specific to Gram-positive species of PDF). The affinity of SB-543668 is threefold higher for E. coli PDF than S. pneumoniae PDF (Table 4), consistent with the single binding mode of this inhibitor to the Gram-negative species.

Discussion

Crystal structures of polypeptide deformylase from S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, H. influenzae, and E. coli reveal significant differences in structure between Gram-negative (H. influenzae, E. coli) and Gram-positive (S. pneumoniae, S. aureus) species. In particular, different structural elements are observed at both the N and C termini of the protein, and one major insertion is observed in the two Gram-negative species studied (Figs. 1 ▶, 2 ▶). This is in agreement with the recently determined crystal structures of S. aureus and B. stearothermophilus PDF (Baldwin et al. 2002; Guilloteau et al. 2002). Despite these structural differences, and the low overall sequence identity between the Gram-negative and Gram-positive species, the active sites of the four species of PDF are remarkably conserved, particularly in the S1′ pocket (Fig. 1 ▶). This is consistent with the conservation in sequence of the active-site region, which is observed across species. The consequence of conservation in active-site structure between S. pneumoniae, S. aureus, H. influenzae, and E. coli PDF is demonstrated by the similar overall binding mode of the small molecule inhibitors SB-485345, SB-543668, and SB-506684 to both S. pneumoniae and E. coli PDF. For these three inhibitors, an aromatic ring is bound in the hydrophobic S1′ pocket of the active site, filling most, but not all, of the available space.

Compared with previously determined crystal structures of PDF complexed with the inhibitors actinonin and BB3497 (Clements et al. 2001; Guilloteau et al. 2002), the structures described here show that it is possible for a small molecule to bind to PDF without forming hydrogen bonds to the main chain of the protein. For the simple inhibitor SB-485345, a binding affinity of 160 nM to E. coli PDF can be achieved by a combination of a good fit in the S1′ pocket and coordination of the bound metal by the reversed hydroxymate group. This structurally minimal inhibitor also demonstrates broad binding specificity across the four species studied (Table 4).

The data in this paper also show that broad binding specificity can be achieved across the species presented here despite subtle differences in active-site structures that can affect the mode of inhibitor binding. For example, the slightly larger size of the S1′ pocket in S. pneumoniae PDF can accommodate both a water molecule and the pyridine group of SB-505684. Although there is not enough room for a water molecule to fill the S1′ pocket of E. coli PDF together with the inhibitor SB-505684, the hydrogen-bonding potential of the pyridine ring is satisfied by Arg 97, a Gram-negative-specific residue. The similar potency of SB-505684 for both Gram-negative and Gram-positive species of PDF shows that, despite the difference in inhibitor binding mode, broad specificity is still maintained.

Similarly, different binding modes are also observed when SB-543668 binds to S. pneumoniae and E. coli PDF. In this case, the presence of Tyr 165 in S. pneumoniae PDF (a Gram-positive-specific residue) provides an additional hydrogen-bonding partner for the carbonyl group of SB-543668, resulting in two possible binding modes of SB-543668 to this species. In E. coli PDF, the equivalent residue is a hydrophobic leucine, and only one major binding mode is observed. It is possible that this difference in binding mode is responsible for the variation in potency of this inhibitor between Gram-negative and Gram-positive species (Table 4).

Taken together, the crystal structures described in this study demonstrate how both the difference in size of the S1′ pocket and specific residue differences (e.g., Arg 97 in E. coli PDF and Tyr 165 in S. pneumoniae PDF) can affect the mode of inhibitor binding to different species of PDF. Despite this, and as observed for SB-505684, the interplay between different residues across species enables broad binding specificity to be achieved. Understanding the interplay between variation in active-site structures across species can be exploited in the design of broad spectrum PDF inhibitors.

Materials and methods

Cloning, expression and purification

PDF purified in the presence of nickel was used for all enzymatic and crystallographic studies. The pdf genes from S. aureus WCUH29, S. pneumoniae R6, E. coli K12, and H. influenzae Q1 were identified in proprietary sequence databases by BLAST homology searching. The genes were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA and cloned in pET plasmids (Novagen) and transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3). Overnight seed cultures were used to inoculate 15 L of LB plus 1% glucose in a 20L Biolafitte fermenter and incubated at 37°C until OD600 nm 0.5. For S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, and H. influenzae PDF the cells were then induced with 0.05 mM IPTG and harvested after 3 h by centrifugation at 4700 rpm (6422g) for 20 min. For E. coli PDF the temperature was reduced to 18°C, and the culture was grown for 20 h prior to harvesting.

For the SeMet-substituted S. pneumoniae PDF, 200 μL of −80°C preserved culture (1-mL aliquots of log phase culture mixed 50:50 with cryopreservative, 10% glycerol/PBS) was inoculated into a 500-mL primary seed flask containing 100 mL of G1X plus 4% glucose supplemented with amino acids (100 mg/L Lys, Thr, Phe, and 50 mg/L Val, Leu, Ile). The seed culture was incubated at 37°C for 20 h, 240 rpm before transfer as a 2% inocula to the second seed, 300 mL G1X plus 4% glucose (supplemented as above) in a 2-L flask. After incubation at 30°C for 20 h, the cells were spun in sterile centrifuge bottles at 4700 rpm (6422g) and then resuspended (in the same volume) of fresh G1X media plus 4% glucose containing the same amino acids with the addition of L-selenomethionine at 60 mg/L. The cells were then incubated at 37°C, induced with 0.05 mM IPTG, and harvested 3 h postinduction by centrifugation.

The cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl at pH 7.0, 5 mM Ni-acetate, lysozyme [1 mg/mL final concentration] plus protease inhibitors), sonicated on ice (5 min, 40 amplitude, 3 sec on/9.9 sec off), spun (100,000g, 60 min, 4°C), filtered (0.2 μm), and loaded onto the first column. The PDF proteins were purified using a three-step process: Ion exchange chromatography (Q-Sepharose FF), with equilibration and loading in 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.0) and elution with a linear gradient of 0–150 mM NaCl, hydroxyapatite chromatography (BioRad 40 um type I) with equilibration and loading in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and elution with 400 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), and size exclusion chromatography (S12 Superose) with elution in 20 mM tris buffer (pH 7.0). The lysis and purification buffers also contained 0.5 mM-mercaptoethanol and 1 mM TCEP (Tris[2-carboxyethylphosphine]hydrochloride) for the purification of the SeMe-substituted S. pneumoniae PDF. For the SeMe-substituted protein all seven methionines were successfully substituted with SeMe as determined by mass spectroscopy.

Enzyme assay

All the reactions were carried out in half-area 96-well microtiter plates (Corning) with a SpectraMax plate reader (Molecular Devices Corp.). PDF activity was measured at 25°C, using a continuous enzyme-linked assay developed by Lazennec and Meinnel (1997) with minor modifications. The reaction mixture contained (in 50 μL) 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6), 15 mM NAD, 0.25 U formate dehydrogenase, and variable concentrations of the substrate peptide formyl-Met–Ala–Ser. The reaction was triggered with the addition of 10 nM PDF enzyme, and absorbance was monitored for 15 min at 340 nm. For determination of Km values, substrate concentration was varied up to 45 mM. A standard curve with NADH concentrations ranging from 0 to 1 mM was performed. The velocities obtained in mOD340 nm per minute were then converted to micromolar NADH produced per second to calculate Vmax. To determine IC50s (the concentration needed to inhibit 50% of enzyme activity), PDF activity was measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of the inhibitor in the presence of an f-MAS concentration corresponding to Km values. The reaction was initiated by the addition of the PDF protein. IC50s were calculated using the equation:

|

where Range is the fitted uninhibited value minus the Background, and s is a slope factor. The equation assumes that y falls with increasing x. All data fitting was carried out with nonlinear least-squares regression using the commercial software package Graphit 4.0 (Erithacus Software Limited).

Synthesis of inhibitors

N-Formyl-N-hydroxy-3-phenylpropylamine, SB 485345

A solution of 3-phenylpropanal (500 mg, 3.73 mmole) in pyridine (5 mL) was treated with hydroxylamine hydrochloride (313 mg, 4.48 mmole) and stirred overnight. The reaction solution was diluted with dichloromethane and extracted with 1 M HCl. The organics were dried and concentrated to provide the oxime (533 mg, 96%) as a 1:1 mixture of cis and trans isomers as a white solid.

To a solution of the above oxime (533 mg, 3.58 mmole) in methanol (20 mL) at 0°C was added 2 mg of methyl orange. With stirring, 1.0 M sodium cyanoborohydride in THF (5.17 mL, 5.17 mmole) was added slowly while simultaneously adding a solution of 6 M HCl/methanol (1/1) dropwise as necessary to maintain the pink color of the methyl orange indicator. After stirring at 0°C for 1 h, the reaction was brought to pH 9 with 6 M NaOH, and the reaction was extracted with dichloromethane. The organics were dried and concentrated to provide the hydroxylamine (517 mg, 95%) as a colorless oil.

A mixture of the above hydroxylamine (517 mg, 3.42 mmole), acetic anhydride (1.6 mL, 17.1 mmole), and formic acid (17 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. The reaction was extractively purified using ethyl acetate and aqueous sodium bicarbonate. The organics were dried and concentrated, and the residue was purified by reverse-phase HPLC to provide N-formyl-N-hydroxy-4-phenylpropylamine, SB-485345, as a colorless oil. MS(ES) m/e = 180.2 [M+H]+.

N-Hydroxy-N-[3-(6-methyl pyridine-2-yl) propyl] formamide, SB 505684

To a stirred solution of oxalyl chloride (5.05 g, 39.7 mmole) in dichloromethane (150 mL) at −78°C was added DMSO (6.2 g, 79.5 mmole), and the resulting mixture was stirred for 5 min. Then 6-methyl-2-pyridinepropanol (5.0 g, 33.1 mmole) as a 10-mL dichloromethane solution was added slowly, and the mixture was stirred a further 30 min at −78°C. After this time, triethylamine (16.7 g, 165 mmole) was added, and the reaction was stirred for an additional 30 min at −78°C. The ice bath was then removed, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 15 min, after which the reaction was diluted with dichloromethane and quenched with water. The layers were separated, and the organics were washed once with water. The combined aqueous layers were then back-extracted twice with dichloromethane. The combined organics were dried and concentrated to produce 6-methyl-2-pyridinepropanal (3.94 g, 80%) as a greenish oil.

A solution of 6-methyl-2-pyridinepropanal (3.94 g, 26.4 mmole) in ethanol (70 mL) was treated with hydroxylamine hydrochloride (3.19 g, 45.6 mmole) and potassium hydroxide (2.55 g, 45.6 mmole), and the reaction mixture was stirred overnight. The reaction solution was concentrated in vacuo by half, then diluted with dichloromethane and water. The layers were separated, and the organics were dried and concentrated to provide the oxime (3.54 g, 82%) as a 1:1 mixture of cis and trans isomers as a yellow oil.

To a solution of the above oxime (3.54 g, 21.6 mmole) in methanol (100 mL) at 0°C was added 2 mg of methyl orange. With stirring, sodium cyanoborohydride (1.36 g, 21.6 mmole) was added slowly while simultaneously adding a solution of 6 M HCl/methanol (1/1) dropwise as necessary to maintain the pink color of the methyl orange indicator. After stirring at 0°C for 1 h, the reaction was brought to pH 9 with 6 M NaOH, and the reaction was extracted with dichloromethane. The organics were dried and concentrated to provide the hydroxylamine (2.71 g, 76%) as a colorless oil.

To a solution of the above hydroxylamine (2.71 g, 16.3 mmole) in dichloromethane (50 mL) was added triethylamine (2.26 mL, 16.3 mmole), followed by freshly prepared mixed anhydride (prepared by heating a mixture of 0.62 mL formic acid and 1.54 mL acetic anhydride at 50°C for 1 h and cooling to room temperature). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and then quenched with water. The layers were separated, and the organics were dried and concentrated. The crude product was purified by reverse-phase HPLC to provide N-hydroxy-N-[3-(6-methyl pyridine-2-yl) propyl] formamide, SB 505684, as a colorless oil. MS(ES) m/e = 195.2 [M+H]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) (4:1 rotameric mixture, major rotamer reported): δ 2.04–2.13 (m, 2H), 2.52 (s, 3), 2.87 (t, 2, J = 5.8), 3.78 (t, 2, J = 5.8), 6.98 (d, 1, J = 7.7), 7.04 (d, 1, J = 7.7), 7.55 (app t, 1, J = 7.7), 8.34 (s, 1).

N-Formyl-N-hydroxy-2-(3-benzoylphenoxy)ethylamine, SB 543668

A solution of t-butyldimethylsilyloxyacetaldehyde (1.0 g, 5.77 mmole) in pyridine (10 mL) was treated with hydroxylamine hydrochloride (485 mg, 6.92 mmole) and stirred overnight. The reaction solution was diluted with dichloromethane and extracted with 1 M HCl. The organics were dried and concentrated to provide the oxime (1.09 g, 99%) as a 1:1 mixture of cis and trans isomers as a colorless oil.

To a solution of the above oxime (1.09 g, 5.76 mmole) in methanol (25 mL) at 0°C was added 2 mg of methyl orange. With stirring, 1.0 M sodium cyanoborohydride in THF (7.47 mL, 7.47 mmole) was added slowly while simultaneously adding a solution of 6 M HCl/methanol (1/1) dropwise as necessary to maintain the pink color of the methyl orange indicator. After stirring at 0°C for 1 h, the reaction was brought to pH 9 with 6 M NaOH, and the reaction was extracted with dichloromethane. The organics were dried and concentrated to provide the hydroxylamine (1.0 g, 91%) as a colorless oil.

To a solution of the above hydroxylamine (1.0 g, 5.24 mmole) in dichloromethane (25 mL) was added triethylamine (0.96 mL, 6.9 mmole), followed by freshly prepared mixed anhydride (prepared by heating a mixture of 0.52 mL formic acid and 1.08 mL acetic anhydride at 50°C for 1 h and cooling to room temperature). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and then quenched with water. The layers were separated, and the organics were dried and concentrated. The crude product was purified by flash chromatography (25%–50% ethyl acetate/hexanes) to provide the N-formylhydroxylamine (410 mg, 36%) as a colorless oil.

SB-543668 was prepared as a member of a small array, for which the general procedure follows: Loading of the N-formyl-N-hydroxylamine onto resin was accomplished by shaking a solution of 2-chlorotrityl resin, the N-formyl-N-hydroxylamine, and triethylamine in dichloromethane overnight. The resin was then washed with dichloromethane, tetrahydrofuran, and again with dichloromethane. Treatment of the loaded resin with TBAF in THF and shaking for 3 h, followed by washing with tetrahydrofuran, dichloromethane, methanol, and again with dichloromethane, provided the free alcohol on the resin. Treatment of the resin-bound alcohol with the appropriate aromatic alcohol (3-hydroxybenzophenone in this case) under Mitsunobu conditions (DIAD, PPh3, THF) overnight, followed by washing with tetrahydrofuran (3 times), dichloromethane, DMF, tetrahydrofuran, and dichloromethane, provided the aromatic ether. Cleavage of the products from support was accomplished by treating the resin with a solution of 5% TFA in methanol for 15 min, followed by washing with dichloromethane then methanol. The filtrate was then concentrated and the crude product purified by high-throughput reverse-phase HPLC to provide pure product, such as N-formyl-N-hydroxy-2-(3-benzoylphenoxy)ethylamine, SB 543668 MS(ES) m/e = 286.3 [M+H]+.

Crystallization

All four proteins were crystallized by vapor diffusion at 20°C using protein at a concentration of 5–12 mg/mL. For crystallization of PDF/inhibitor complexes, inhibitors were prepared at a concentration of 5 mg/mL in 25% DMSO and incubated with protein at a 10-fold molar excess for 24 h prior to crystallization. All crystals were grown using a well solution of 1.8–2.8 M ammonium sulfate, 1%–3% PEG400, 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5), except for E. coli PDF/SB-485345, which was grown from 30% PEG3000, 0.2 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M sodium cacodylate (pH 6.5), and H. influenzae PDF/SKF-107991, which was grown from 20% PEG8000, 0.05 M monopotassium dihydrogen phosphate. Cryobuffer was added directly to the drops containing crystals and after 2–3 min, the crystals were frozen by dunking into liquid nitrogen. For crystals grown from ammonium sulphate a cryobuffer of 15% glycerol, 3.0 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M sodium HEPES was used, whereas for E. coli PDF/SB-485345 and H. influenzae PDF/SKF-107991, the cryobuffer was well solution containing 15% glycerol.

Data collection and structure determination

Data processing was carried out with DENZO and SCALEPACK (Otwinowski 1993). For S. pneumoniae PDF/SB-485345, all seven Se were located using the program SOLVE (FOM = 0.74; Terwilliger and Berendzen 1999). Initial phase estimates were refined by solvent flattening and histogram mapping using the program DM (CCP4 1994). Model building was carried out using the program O (Jones et al. 1991), and refinement was carried out with the program CNX (Brunger et al. 1998) using standard refinement protocols. Initial model building and refinement were carried out using the peak wavelength data set. Final stages of refinement were carried out using the S. pneumoniae PDF/SB-485345 native dataset (Table 2). The final model of S. pneumoniae PDF/SB-485345 contains residues 1–203, 187 water molecules, 1 sulfate ion, one inhibitor molecule, and 1 nickel ion. Residues 92–99 are disordered and have not been included in the final model. S. pneumoniae PDF/SB-505684 and S. pneumoniae PDF/SB-505684 were solved by molecular replacement using the final model of S. pneumoniae PDF/SB-485345 with the inhibitor, water, and metal atom removed. The final models of S. pneumoniae PDF/SB-505684 and S. pneumoniae PDF/SB-505684 also contain residues 1–203 (residues 92–99 are disordered), 1 sulfate ion, and 1 nickel atom (final statistics in Table 2). For the structure S. pneumoniae PDF/SB-505684, the two conformations of inhibitor molecule were each refined with an occupancy of 0.5.

S. aureus PDF/apo was solved by Molecular Replacement with the program AMoRe (CCP4 1994) using the refined structure of S. pneumoniae PDF/SB-485345 as a search model. Before molecular replacement, the inhibitor, Ni atom, and water molecules were removed, and residues that were different between S. pneumoniae PDF and S. aureus PDF were changed to alanine. The rotation search gave one clear solution (correlation coefficient 20.3). The translation search placed one molecule in the asymmetric unit. This solution was fixed and used to place the second molecule in the asymmetric unit. Rigid body refinement of the molecular replacement solution in CNX (data 10–3.0 Å) yielded Rfree = 30.3%, Rwork = 31.4%. Model building was carried out using the program O and refinement was carried out in CNX using standard positional refinement and B-factor refinement protocols. Noncrystallographic symmetry restraints were applied for the first cycles of refinement and lifted for the final round of refinement. The final model contains 265 water molecules, 2 Ni atoms, and 1 sulfate ion (final statistics in Table 2).

E. coli PDF inhibitor structures and H. influenzae PDF/SKF-107991 were solved by molecular replacement with the program AMoRe using published coordinates (PDB ID code, 1bsz) as a search model. Prior to molecular replacement, water molecules, metal ions, and PEG molecules were removed and for H. influenzae PDF, residues that were different from E. coli PDF were changed to alanine. Model building was carried out using the program O, and refinement was carried out with CNX. Noncrystallographic symmetry restraints were applied for the first cycles of refinement and lifted for the final rounds of refinement (final statistics in Table 2). For all three E. coli PDF/inhibitor structures the final models contain two sulfate ions, three inhibitor molecules, and three Ni atoms. For H. influenzae PDF/SKF-107991, the final model contains 241 water molecules, three inhibitor molecules, and three nickel atoms.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Benjamin Bax, Cheryl Janson, and Nino Campobasso for helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript, and staff at the ESRF for help with data collection.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.0229303.

References

- Adams, J. 1968. On the release of the formyl group from nascent protein. J. Mol. Biol. 33 571–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J. and Capecchi, M. 1996. The role of N-formylmethionine-s RNA as the initiator of protein synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 55 147–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, E., Harris, M., Yem, A., Wolfe, C., Vosters, A., Curry, K., Murray, R., Bock, J., Marshall, V., Cialdella, J., et al. 2002. Crystal structure of type II peptide deformylase from Staphylococcous aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 277 31163–31171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, A., Schlichting, I., Kabsch, W., Groche, D., Schultz, S., and Wagner, A. 1998a. Iron centre, substrate recognition and mechanism of peptide deformylase. Nat. Struc. Biol. 5 1053–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, A., Schlichting, I., Kabsch, W., Schultz, S., and Wagner, A. 1998b. Structure of peptide deformylase and identification of the substrate binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 273 11413–11416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger, A., Adams, P., Clore, G., DeLano, W., Gross, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R., Jiang, J., Kuszewiski, J., Nilges, M., and Pannu, N. 1998. Crystallography and NMR system; a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D 54 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson, M. 1991. Ribbons 2.0. Appl. Crystallography 24 958–961. [Google Scholar]

- CCP4. 1994. The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 50 760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, M., Gong, W., Ravi Rajagopalan, P., Hao, B., Tsai, C., and Pei, D. 1997. Crystal structure of the Escherichia coli peptide deformylase. Biochemistry 36 13904–13909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements, J., Beckett, R., Brown, A., Catlin, G., Lobell, M., Palan, S., Thomas, W., Whittaker, M., Wood, S., Salama, S., et al. 2001. Antibiotic activity and characterisation of BB-3497, a novel peptide deformylase inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2 563–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dardel, F., Ragusa, S., Lazennec, C., Blanquet, S., and Meinnel, T. 1998. Solution structure of nickel-peptide deformylase. J. Mol. Biol. 280 501–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglione, C., Serero, A., Pierre, M., Boisson, B., and Meinnel, T. 2000. Identification of eukaryotic peptide deformylases reveals universality of N-terminal processing mechanisms. EMBO J. 19 5916–5929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groche, D., Becker, A., Schlichting, I., Kabsch, W., Schultz, S., and Wagner, A. 1998. Isolation and crystallisation of functionally competent Escherichia coli peptide deformylase forms containing either iron or nickel in the active site. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Com. 246 342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilloteau, J.-P., Mathieu, M., Giglione, C., Blanc, V., Dupuy, A., Chevrier, M, Gil, P., Famechon, A., Meinnel, T., and Mikol, V. 2002. The crystal structures of four peptide deformylases bound to the antibiotic actinonin reveal two distinct types: A platform for the structure-based design of antibacterial agents. J. Mol. Biol. 320 951–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao, B., Gong, W., Ravi Rajagopalan, P., Zhou, Y., Pei, D., and Chan, M. 1999. Structural basis for the design of antibiotics targeting peptide deformylase. Biochemistry 38 4712–4719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T., Zou, J.-Y., and Cowan, S. 1991. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A 47 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch, W., and Sander, C. 1983. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: Pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22 2577–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A., Nguyen, K., Srivathsan, S., Ornstein, B., Turley, S., Hirsh, I., Pei, D., and Hol, W. 2002. Crystals of peptide deformylase from Plasmodium falciparum reveal critical characteristics of the active site for drug design. Structure 10 357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazennec, C. and Meinnel, T. 1997. Formate dehydrogenase-coupled spectrophotometric assay of peptide deformylase. Anal. Biochem. 244 180–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, D. and Leder, P. 1969. Deformylation and protein synthesis. Biochemistry 8 435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcker, K. and Sanger, F. 1964. N-Formyl-methionyl-sRNA. J. Mol. Biol. 8 835–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, P., Hackbarth, C., Young, D., Wang, W., Chen, D., Yuan, D., White, R., and Trias, J. 2000. Peptide deformylase in Staphylococcus aureus: Resistance to inhibition is mediated by mutations in the formyltransferase gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44 1825–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazel, D., Pochet, S., and Marliere, P. 1994. Genetic characterisation of polypeptide deformylase, a distinctive enzyme of eubacterial translation. EMBO J. 13 914–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRee, D.E. 1993. Practical protein crystallography. Academic Press, New York.

- Meinnel, T. and Blanquet, S. 1995. Enzymatic properties of Escherichia coli peptide deformylase. J. Bacteriol. 177 1883–1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinnel, T., Lazennec, C., and Blanquet, S. 1995. Mapping of the active site zinc ligands of peptide deformylase. J. Mol. Biol. 254 175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinnel, T., Lazennec, C., Villoing, S., and Blanquet, S. 1997. Structure–function relationships within the peptide deformylase family. Evidence for a conserved architecture of the active site involving three conserved motifs and a metal ion. J. Mol. Biol. 267 749–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell, J., Pryor, K., Grant, S., and Leiting, B. 1999. A high quality nuclear magnetic resonance solution structure of peptide deformylase from Escherichia coli: Application of an automated assignment strategy using GARANT. J. Biomol. NMR 13 311–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski, Z. 1993. Data collection and processing. In Proceedings of CCP4 Study Weekend. (eds. L. Sawyer et al.), pp. 56–62. SERC Daresbury Laboratory, Warrington, UK.

- Pei, D. 2001. Peptide deformylase: A target for novel antibiotics? Emerg. Therapeut. Targets 5 23–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragusa, S., Blanquet, S., and Meinnel, T. 1998. Control of peptide deformylase activity by metal cations. J. Mol. Biol. 280 515–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan, P.T.R., Yu, X.C., and Pei, D. 1997. Peptide deformylase: A new type of mononuclear iron protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119 12418–12419. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan, P.T.R., Grimme, S., and Pei, D. 2000. Characterisation of cobalt (II)-substituted peptide deformylase: Function of the metal ion and the catalytic residue Glu-33. Biochemistry 39 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, M. and Webster, R. 1968. Protein chain initiation and deformylation in B. subtilis homogenates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 60 1487–1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger, T. and Berendzen, J. 1999. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D 55 849–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster, R., Engelhardt, D., and Zinder, N. 1996. In vitro protein synthesis: Chain initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 55 155–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]