Abstract

Iron is an essential nutrient for the survival of most organisms and has played a central role in the virulence of many infectious disease pathogens. Mycobacterial IdeR is an iron-dependent repressor that shows 80% identity in the functional domains with its corynebacterial homologue, DtxR (diphtheria toxin repressor). We have transformed Mycobacterium tuberculosis with a vector expressing an iron-independent, positive dominant, corynebacterial dtxR hyperrepressor, DtxR(E175K). Western blots of whole-cell lysates of M. tuberculosis expressing the dtxR(E175K) gene revealed the stable expression of the mutant protein in mycobacteria. BALB/c mice were infected by tail vein injection with 2 × 105 organisms of wild type or M. tuberculosis transformed with the dtxR mutant. At 16 weeks, there was a 1.2 log reduction in bacterial survivors in both spleen (P = 0.0002) and lungs (P = 0.006) with M. tuberculosis DtxR(E175K). A phenotypic difference in colonial morphology between the two strains also was noted. A computerized search of the M. tuberculosis genome for the palindromic consensus sequence to which DtxR and IdeR bind revealed six putative “iron boxes” within 200 bp of an ORF. Using a gel-shift assay we showed that purified DtxR binds to the operator region of five of these boxes. Attenuation of M. tuberculosis can be achieved by the insertion of a plasmid containing a constitutively active, iron-insensitive repressor, DtxR(E175K), which is a homologue of IdeR. Our results strongly suggest that IdeR controls genes essential for virulence in M. tuberculosis.

With more than one-third of the world’s population latently infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the global burden of tuberculosis is staggering. The emergence of multidrug- resistant strains and the increased susceptibility of the HIV-infected further highlights the need for elucidation of the molecular pathogenesis of M. tuberculosis and its virulence genes. Iron plays a critical role in the regulation of virulence of many bacterial pathogens. (1) In tuberculosis, there is indirect clinical and in vitro evidence that iron regulation is important to the virulence of this microbial pathogen (2–5).

In a phylogenetically related organism, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, iron depletion results in the derepression of virulence genes such as the diphtheria toxin (tox) gene by DtxR (diphtheria toxin repressor). The corynebacterial DtxR has a homologue in M. tuberculosis, IdeR (iron-dependent repressor). In the amino terminal 140 aa that contain the Fe2+ and DNA-binding domains of DtxR, IdeR shares 80% identity with DtxR (6). In 1995, ideR was first described by Doukhan et al. (7) in conjunction with the sigA sigB cluster of genes. Subsequently, the ability of mycobacterial IdeR to bind to the corynebacterial tox operator region in a metal ion-dependent manner was demonstrated by gel-shift assay (8). Mutation of ideR in M. smegmatis resulted in derepressed siderophore production in high iron conditions (9). These findings parallel those described in corynebacterial dtxR and suggest that the homology between these two genes may allow for cross-genus functional complementation.

Using a positive genetic selection system to clone dtxR alleles, Sun et al. (10) recently isolated and characterized a series of DtxR mutants created by PCR mutagenesis. One of the mutants that bound to the tox operator (toxO) and constitutively repressed reporter gene expression in an iron-independent manner was characterized and found to have a single amino acid substitution of lysine for glutamic acid at position 175 [DtxR(E175K)]. In merodiploid strains harboring both wild-type dtxR and mutant dtxR(E175K) genes, Sun et al. found the mutant to be dominant over the wild-type allele. We postulated that this dominant corynebacterial mutant may be able to constitutively repress IdeR-regulated genes in M. tuberculosis. To test this hypothesis, we constructed an M. tuberculosis strain expressing the dtxR(E175K) positive dominant allele and tested its virulence in a mouse model of tuberculosis.

Methods

Strains, Plasmids, and Cultures.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1 (10–14). Escherichia coli cultures were grown in LB or Luria agar supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) or hygromycin (200 μg/ml). M. tuberculosis CDC1551 and M. smegmatis cultures were grown in standard Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco), supplemented with albumin dextrose complex, 0.1% glycerol, and 0.05% Tween 80 at 37°C in roller bottles (15).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain/plasmid | Genotype/description | Source/reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pNBV1 | E. coli-mycobacterial shuttle vector ApR, HyR | 12 |

| pSDM2 | pSC101-derivative containing the dtxR(E175K) gene, KmR | 10 |

| pNBV1/SAD | pNBV1 containining the dtxR(E175K) gene, ApR, HyR | This paper |

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | F−recA1, hsdR17, thi-1, gyrA96, supE44, endA1, relA1, recA1, deoR, Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 (Φ80 lacZΔM15) | 14 |

| M. smegmatis mc26 1-2C | Transformable variant of mc26 | 13 |

| M. tuberculosis CDC1551 | Virulent recent clinical isolate | 11 |

| M. tuberculosisDtxR(E175K) | M. tuberculosis CDC1551 harboring pNBV1/SAD | This paper |

Hy, hygromycin; Ap, ampicillin; Km, kanamycin.

Construction of dtxR(E175K) Shuttle Plasmid.

A 1.5-kb BamHI–HindIII fragment of DNA from pSDM2 was cloned into pNBV1. The resulting recombinant plasmid, pNBV1/SAD (self-activating DtxR), was cloned in E. coli DH5α and purified by using the Qiagen system (Qiagen, Chatsworth, CA) (16). Purified plasmids then were electroporated into M. tuberculosis CDC1551 by standard protocols (15).

Western Blot Analysis.

Recombinant E. coli and mycobacteria were lysed in 3 M urea, 0.5% Triton X-100, 3.25 μM DTT, 2% Pharmalyte (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), 100 μg/ml PMSF, and 2 μg/ml leupeptin. Using 0.1-mm glass beads, the samples were homogenized twice in a Mini-bead-beater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK) at maximum speed for 1 min. Samples were centrifuged to remove cellular debris and unlysed cells. After separation by 12% SDS/PAGE, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond, Amersham Pharmacia) by semidry technique (Transblot SD, Hercules, CA) and blocked with 5% nonfat milk in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) for 1 hr. Membranes then were incubated overnight in PBS-T with rabbit anti-DtxR polyclonal antibodies at the appropriate concentration at 4°C (17). After washing, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody diluted in PBS-T for 2 hr. The Supersignal Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce) was used for autoradiograph development.

Murine Tuberculosis Infection Model.

BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old) were infected by tail vein injection with 2 × 105 organisms of wild-type or M. tuberculosis DtxR(E175K). Bacterial infection was monitored over a 119-day period. Colony-forming units (cfu) in spleen and lungs were assessed at 4-week intervals by serial dilutions of organ homogenates plated on 7H10 Middlebrook agar containing 50 μg/ml cycloheximide, 50 μg/ml carbenicillin, 20 μg/ml trimethoprim, and 200 units/ml polymyxin (18).

DNA Gel-Shift Binding Assay.

The DNA migration retardation assay was performed as described (19). Purified DtxR protein was isolated by methods as described (20). Radiolabeled DNA iron box fragments were generated by PCR using 100 ng of 32P-end-labeled primer mixed with 150 ng of unlabeled primer and template DNA from gel-purified 100-bp cold fragments containing the iron box of interest. Binding reactions were carried out in 10 mM Tris⋅OAc (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, and 50 μg/ml calf thymus DNA. Binding reactions were equilibrated for 30 min and then loaded onto a nondenaturing 6% acrylamide gel (21).

Results

Expression of the Corynebacterial dtxR Gene in Mycobacteria.

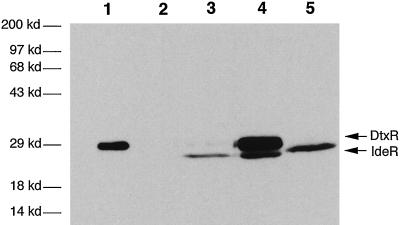

The 1.5-kb corynebacterial DNA fragment cloned in pNBV1/SAD contained 500 bp of 5′ noncoding sequences as well as the entire dtxR(E175K) ORF. To determine whether the corynebacterial mutant dtxR(E175K) gene was expressed in mycobacteria, we transformed M. smegmatis, a fast-growing strain of mycobacteria, with pNBV1/SAD. Whole-cell lysates prepared from M. smegmatis cultures were separated by 12% SDS/PAGE. Fig. 1 shows a Western blot developed with polyclonal anti-DtxR antibodies. As may be seen, these antibodies recognize both DtxR and IdeR because of their significant antigenic similarity. Although the deduced molecular mass of IdeR (25.2 kDa) differs by only 0.1 kDa from DtxR (25.3 kDa) we have repeatedly observed anomalous accelerated migration of IdeR in our SDS/PAGE gels in which it runs at 23 kDa in spite of its mass of 25 kDa. This phenomenon also has been noted by Schmitt et al. (8). In preparations from M. smegmatis harboring pNBV1/SAD (Fig. 1, lane 4), two distinct bands appear. Because dtxR(E175K) is expressed from a multicopy plasmid, significantly more DtxR(E175K) protein is made than the chromosomally expressed IdeR. Similar results in M. tuberculosis transformed with pNBV1/SAD also were found (results not shown). The in vitro growth rate of wild-type M. tuberculosis was indistinguishable from that of M. tuberculosis DtxR(E175K) by the Bactec radiometric growth monitoring system.

Figure 1.

Western blot of cell lysates incubated with polyclonal antibody against DtxR. Lane 1, purified DtxR (25.3 kDa). Lanes 3 and 5, lysates from wild-type M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis, respectively, expressing native IdeR (25.2 kDa.). Lane 4, lysate from the M. smegmatis heterodiploid harboring pNBV1/SAD expressing both DtxR(E175K) and IdeR. The molecular masses, determined by size standards, are shown at left.

Attenuation of Virulence in M. tuberculosis Expressing the Constitutively Active DtxR Hyperrepressor.

After confirming that the corynebacterial mutant dtxR was expressed in transformed mycobacteria, we turned to an in vivo animal model to test the effect of the hyperrepressor on virulence. Forty-eight BALB/c mice were inoculated with 2 × 105 cfu of M. tuberculosis CDC1551 or M. tuberculosis DtxR(E175K) by tail-vein injection. Both animal weights and the tissue burden of surviving bacteria were monitored over time. Mice infected with wild-type M. tuberculosis began to lose weight beginning at 13 weeks whereas the M. tuberculosis DtxR(E175K)-infected animals initially gained weight, then maintained stable weights for the duration of the experiment. At 17 weeks, there was a statistically significant difference of 1.7 g (P = 0.006 by two-tailed t test) between the wild-type and DtxR(E175K) groups.

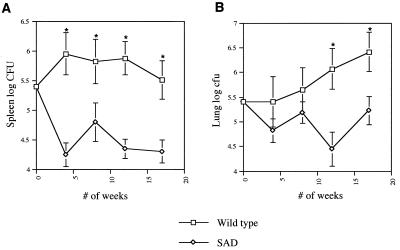

Fig. 2 shows the survival of the two M. tuberculosis strains in lungs and spleens of mice over time. At 17 weeks, there was a 1.2 log attenuation in virulence of the DtxR(E175K)-expressing strain compared with wild type, which was statistically significant in both spleen (P = 0.0002) and lungs (P = 0.006). Analysis of the colonies from the mouse tissues at 12 weeks showed that 99% of the colonies were hygromycin resistant, indicating maintenance of the pNBV1/SAD plasmid. Histopathologic inspection of spleen and lungs of wild-type and DtxR(E175K)-expressing strains corroborated our cfu data with fewer visible acid fast bacilli at 17 weeks in histologic sections of mouse organs from animals infected with the M. tuberculosis DtxR(E175K) than with the wild type.

Figure 2.

Virulence comparison of wild-type M. tuberculosis and M. tuberculosis DtxR(E175K) mutant. (A) The log cfu of the homogenized spleens of mice sacrificed at 4-week intervals. (B) The log cfu of homogenized lungs at 4-week intervals. Each point represents the mean log cfu of 5–6 mice ± 1 SD (error bars). * denote statistically significant differences between groups at a given time point.

Differences in Colonial Morphology Between Strains.

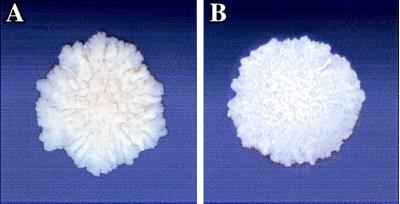

Colonies of M. tuberculosis DtxR(E175K) grown from frozen stocks on 7H10 Middlebrook agar showed no difference in growth rate in vitro as compared with wild-type CDC1551, but were noted to have a distinct colonial morphology (see Fig. 3). The recombinant strain colonies were rougher, appeared to be drier, and were more raised and wrinkled than wild-type colonies. In addition, yellow pigmentation was noted in the DtxR(E175K) expressor. Both strains exhibited a spreading phenotype and were crenelated at the periphery.

Figure 3.

(A) A 10-week-old representative colony of M. tuberculosis DtxR(E175K) on 7H10 agar. (B) A 10-week-old representative colony of wild-type M. tuberculosis (strain CDC1551) on 7H10 agar.

Identification of Iron Boxes.

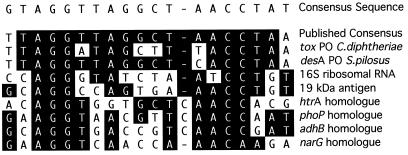

An imperfect palindromic consensus sequence of the iron box for DtxR/IdeR has been established by in vivo and in vitro methods (8, 22, 23). This consensus sequence is listed at the top of Fig. 4. To identify genes that may be regulated by IdeR, we searched the M. tuberculosis genome for iron boxes that were in untranslated regions within 200 bp of an ORF. We chose two half-site sequences with allowance for a variable number of intervening base pairs for our search. In the 4.41MB of the M. tuberculosis genome (24), 58 sequences with acceptable homology to the consensus sequence were identified. Six of these were in untranslated regions and had corresponding downstream ORFs.

Figure 4.

Alignment of the iron box consensus sequence, known DtxR binding sites, and putative M. tuberculosis DtxR/IdeR binding sites identified by an in silico genome search. The consensus sequence at the top represents the compilation of the nine aligned sequences shown. The published consensus is drawn from the literature. Gene homologues of the downstream ORFs are shown on the right.

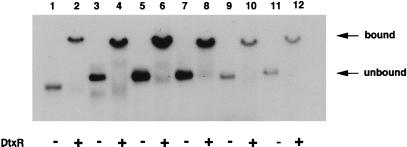

A DNA gel-binding assay was used to assess the ability of DtxR to bind to these putative iron-regulated operator regions drawn from the M. tuberculosis genome. Fig. 5 shows the results of gel-binding assays using 32P-end-labeled 100-bp DNA fragments containing five of the putative iron boxes (IB1–5). Binding of DtxR to the tox operator could be abolished with the addition of unlabeled tox DNA, but not with nonspecific DNA. All five of these putative iron boxes were bound by DtxR to a similar degree as that observed with the tox operator. The iron box upstream of the narG homologue, IB6, did not bind to DtxR (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Autoradiographs of gel-binding assay between DtxR and putative M. tuberculosis DtxR/IdeR binding sites. Shown are 100-bp 32P-end-labeled DNA fragments containing toxO (lanes 1 and 2), IB-1 (lanes 3 and 4), IB-2 (lanes 5 and 6), IB-3 (lanes 7 and 8), IB-4 (lanes 9 and 10), and IB-5 (lanes 11 and 12) separated in a nondenaturing 6% polyacrylamide gel. Odd-numbered lanes contain DNA only (unbound), and even-numbered lanes contain DNA preincubated with purified DtxR (bound).

Table 2 identifies the ORFs downstream of these six iron boxes. blast searches reveal that these genes encode a PhoP homologue (a transmembrane sensor of a two-component sensor-regulator pair), a homologue of the HtrA serine protease, 16S ribosomal RNA, an alcohol dehydrogenase AdhB, and a homologue of the M. tuberculosis 19-kDa antigen (a protein shown to be involved in the human immune response to tuberculosis) (25). IB6, which was not shifted by DtxR in vitro, appears upstream of a nitrate reductase subunit gene, narG.

Table 2.

Iron boxes (IB)

| Name | Downstream ORF | Accession number | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| IB-1 | PhoP homologue | Rv0761c | Two-component phosphotransferase regulatory protein |

| IB-2 | AdhB | Rv0757 | Alcohol dehydrogenase |

| IB-3 | HtrA homologue | Rv0983 | Serine protease, HtrA-antigen family |

| IB-4 | rrnA | MTB00368 | 16S ribosomal RNA protein |

| IB-5 | Hypothetical protein | Rv3764c | Predicted ORF with 26% similarity to M. tuberculosis 19-kDa antigen beginning at base 4,210,314 |

| IB-6 | NarG | Rv1161 | Respiratory nitrate reductase alpha subunit |

Discussion

The concentration of free ferrous iron (Fe2+) is extremely limited in vivo. For this reason, many pathogenic prokaryotes such as Vibrio cholerae, E. coli, Neisseria gonorhoeae, and C. diphtheriae coregulate virulence gene expression with iron sensing and scavenging systems (26–28). In C. diphtheriae, one such mechanism of iron regulation relies on a repressor, DtxR, which binds to a specific palindromic sequence in the operator regions of the genes that it controls (29). In low iron states, the metal ion triggered conformational change that allows it to bind to the DNA is disrupted, the repressor loses affinity for the operator site, and gene expression occurs. Recently, a positive dominant DtxR(E175K) mutant unresponsive to iron was generated by random PCR mutagenesis using a genetic selection system (10).

Significant amino acid identity between corynebacterial DtxR and mycobacterial IdeR has been described. In the amino terminal 140 aa there is a DNA binding helix–turn–helix motif, a primary metal ion binding site, and a protein–protein interaction domain. Corynebacterial DtxR and mycobacterial IdeR share 80% amino acid identity in this portion of both proteins. Evidence of functional homology between IdeR and DtxR has been shown previously by Schmitt et al. (8). Because these two organisms are phylogenetically related, we postulated that the iron-independent corynebacterial DtxR(E175K) may be able to repress the expression of genes under the control of IdeR in mycobacteria in a constitutive fashion.

In this paper, we have shown that the positive dominant DtxR(E175K) iron-independent repressor is expressed in mycobacteria and furthermore, that it is able to attenuate M. tuberculosis in a murine model of infection. Rational attenuation of M. tuberculosis offers the possibility of defining specific virulence factors of the organism and of developing live vaccines superior to bacillus Calmette–Guérin. However, gene replacement has proven difficult in M. tuberulcosis because of high rates of illegitimate recombination. Addition of a dominant mutant gene is technically simpler than gene replacement in M. tuberculosis and permits comparison of a defined merodiploid strain with an isogenic wild-type strain. There are reports of E. coli genes introduced into other bacteria to regulate the expression of endogenous genes. In a paper by de Henestroza et al. (30), a mutant E. coli recA gene produced aberrancies in SOS gene induction when expressed in heterologous Gram-negative systems. Although we did not compare a M. tuberculosis strain containing empty plasmid with wild-type M. tuberculosis, there are several reasons it is unlikely that the presence of a multicopy plasmid produces nonspecific attenuation. First, our in vitro Bactec comparison showed no differences in the rate of growth of the mutant strain as compared with wild type. In addition, studies of deletion mutants of M. tuberculosis have shown that plasmid complementation fully restores virulence, suggesting that there is little cost to the organism to maintain the plasmid (31, 32).

Animal models have shown that inactivation and clearance of virulent M. tuberculosis in liver and spleen is effectively accomplished, but that the same cell-mediated immune mechanisms appear relatively ineffective in lungs. These data point to a difference in the intracellular microenvironment of the lung granuloma (33). It has been postulated from bacillus Calmette–Guérin and H37Ra data that avirulent or attenuated strains lack the genes required for effective growth within lung phagocytes (34). Our data suggest that IdeR may regulate genes important for M. tuberculosis survival late in lung infection as attenuation seems to increase dramatically at 12 weeks after infection. This timing may correlate with the onset of granuloma formation in mouse lungs and the need for M. tuberculosis to scavenge iron from extracellular rather than intracellular sources (35).

The ideR gene has been found in M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, and M. smegmatis. In M. smegmatis, an ideR mutant showed defective regulation of siderophore biosynthesis (9). Potential IdeR binding sites upstream of exochelin biosynthesis genes, such as fxbA, recently have been confirmed (36, 37). In addition, several IdeR recognition sequences have been identified by using computer searches of the M. tuberculosis genome (38). We have similarly identified six potential IdeR-binding sites in M. tuberculosis, five of which demonstrated significant binding with DtxR in a gel-shift assay. We postulate that the sixth sequence was unable to bind in our in vitro assay because of incorrect spacing between the two relatively well-conserved half-sites. We used DtxR rather than IdeR in this gel-shift assay because we specifically sought to identify genes responsible for the attenuated phenotype of M. tuberculosis DtxR(E175K). The predicted ORF downstream of IB-1 encodes a homologue of phoP, a phosphotransfer response regulator. A number of two-component pairs have been shown to regulate virulence pathways in bacterial pathogens. These include BvgA/BvgS in Bordatella pertussis, VanR/VanS in Enterococcus faecium, PhoP-PhoQ in Salmonella typhimurium, and OmpT/EnvZ in Shigella flexneri (39, 40). In M. tuberculosis, a two-component pair, mtrA-mtrB, has been described previously and appears to play an intracellular role as expression of mtrA increases upon entry into macrophages (41). Furthermore, phoP mutants in Salmonella are unable to synthesize many of the proteins expressed on interaction with macrophages (42). Downstream of IB-2 is adhB, an alcohol dehydrogenase. In S. typhimurium, it has been postulated that alcohol dehydrogenase genes such as eutG may confer a protective role from reactive aldehyde intermediates associated with inflammatory cell activation (43).

IB-3 lies upstream of an ORF homologous to a HtrA-like serine protease, which in E. coli is thought to be required for growth of the organism at high temperature, and may play a role in degrading abnormal proteins within the periplasm (44, 45). It is a known virulence factor in several organisms including S. typhimurium, Yersinia enterocolitica, Brucella abortus, and Brucella melitensis (46–49). In an animal model, a S. typhimurium htrA mutant is attenuated and a safe and immunogenic live vaccine strain in mice (50). Both M. avium subsp. paratuberculosis and M. tuberculosis have putative serine proteases with significant homology to HtrA (24, 51).

IB-4 lies upstream of rrnA, a 16S rRNA gene that has been shown to be part of a group of rDNA operons in both slow and fast-growing mycobacteria with hypervariable multiple promoter regions. The M. tuberculosis rrnA operon has two promoters, one of which is conditionally induced, suggesting complex regulation of this essential gene (52).

Our results indicate that a dominant positive corynebacterial dtxR allele can attenuate the virulence of M. tuberculosis in a murine model. These data implicate the M. tuberculosis IdeR repressor as a regulator of genes essential for full virulence. Expanded study of IdeR and the genes under its control offers a promising avenue toward understanding the pathogenicity of M. tuberculosis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to J. Gomez for assistance with in silico searches. Y.C.M. is supported by a Heiser Foundation Research Grant. This work also is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants A136973 and AI37856.

Abbreviations

- IdeR

iron-dependent repressor

- DtxR

diphtheria toxin repressor

- cfu

colony-forming units

- SAD

self-activating DtxR

References

- 1.Litwin C M, Calderwood S B. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:137–149. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kochan I. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1973;60:1–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-65502-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raghu B, Raghupati S, Venkatesan P. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1993;31:341–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray M J, Murray A B, Murray M B, Murray C J. Br Med J. 1978;2:1113–1115. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6145.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordeuk V R, McLaren C E, MacPhail A P, Deichsel G, Bothwell T H. Blood. 1996;87:3470–3476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White A, Ding X, vanderSpek J, Murphy J R, Ringe D. Nature (London) 1998;394:502–506. doi: 10.1038/28893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doukhan L, Predich M, Nair G, Dussurget O, Mandic-Mulec I. Gene. 1995;165:67–70. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00427-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitt M P, Predich M, Doukhan L, Smith I, Holmes R K. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4284–4289. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4284-4289.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dussurget O, Rodriguez M, Smith I. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:535–544. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.1461511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun L, vanderSpek J, Murphy J R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14935–14940. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valway S E, Sanchez M P C, Shinnick T F, Orme I, Agerton T, Hoy D, Jones J S, Westmoreland H, Onorato I M. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:633–639. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803053381001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard N S, Gomez J E, Ko C, Bishai W R. Gene. 1995;166:181–182. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00597-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Lathigra R, Garbe T, Catty D, Young D. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:381–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bethesda Research Laboratories. Bethesda Research Laboratory Focus. Vol. 8. 1986. p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobs W R, Jr, Kalpana G V, Cirillo J D, Pascopella L, Snapper S B, Udani R A, Jones W, Barletta R G, Bloom B R. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:537–555. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04027-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Wiley; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tao X, Boyd J, Murphy J R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5897–5901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyazaki E, Miyazaki M, Chen J M, Chaisson R E, Bishai W R. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:85–89. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hendrickson W, Schleif R F. J Mol Biol. 1984;178:611–628. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tao X, Zeng H-Y, Murphy J R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6803–6807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saviola B, Seabold R, Schleif R F. J Mol Biol. 1998;278:539–548. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tao X, Schiering N, Zeng H-Y, Ringe D, Murphy J R. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:191–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmitt M P, Holmes R K. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1141–1149. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.4.1141-1149.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Tekaia F, et al. Nature (London) 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Husson R N, Young R A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1679–1683. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.6.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldberg M B, DiRita V J, Calderwood S B. Infect Immun. 1990;58:55–60. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.1.55-60.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Calderwood S B, Mekalanos J J. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4759–4764. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.10.4759-4764.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morse S A, Chen C, LeFaou A, Mietzner T A. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:s306–s310. doi: 10.1093/cid/10.supplement_2.s306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boyd J, Oza M N, Murphy J R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5968–5972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Henestroza A R F, Calero S, Barbe J. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;226:503–506. doi: 10.1007/BF00260664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berthet F-X, Lagranderie M, Gounon P, Laurent-Winter C, Ensergueix D, Chavarot P, Thouron F, Maranghi E, Pelicic V, Portnoi D, et al. Science. 1998;282:759–762. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson M, Phalen S W, Lagranderie M, Ensergueix D, Chavarot P, Marchal G, McMurray D N, Gicquel B, Guilhot C. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2867–2873. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2867-2873.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Collins F M. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1993;19:1–16. doi: 10.3109/10408419309113520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pascopella L, Collins F M, Margin J M, Jacobs W R J, Bloom B R. Infect Agents Dis. 1993;2:282–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Long E R, editor. The Chemistry and Chemotherapy of Tuberculosis. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1958. pp. 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiss E H, Yu S, Jacobs W R J. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:557–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dussurget O, Timm J, Gomez M, Gold B, Yu S, Sabol S Z, Holmes R K, Jacobs W R, Smith I. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3402–3408. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3402-3408.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dussurget O, Smith I. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:354–358. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Groisman E A, Heffron F. In: Two-Component Signal Transduction. Hoch J A, Silhavy T J, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1995. pp. 319–332. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dziejman M, Mekalanos J J. In: Two-Component Signal Transduction. Hoch J A, Silhavy T J, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol.; 1995. pp. 305–317. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Via L E, Curcic R, Mudd M H, Dhandayuthapani S, Ulmer R J, Deretic V. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3314–3321. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3314-3321.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buchmeier N A, Heffron F. Science. 1990;248:730–732. doi: 10.1126/science.1970672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stojiljkovic I, Baumler A J, Heffron F. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1357–1366. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1357-1366.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lipinska B, Fayet O, Baird L, Georgopoulos C. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1574–1584. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1574-1584.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strauch K L, Beckwith J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1576–1580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson K, Charles I, Dougan G, Pickard K, O’Gaora P, Costa G, Ali T, Miller I, Hormaeche C. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:401–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamamoto T, Hanawa T, Ogata S, Kamiya S. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2980–2987. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.2980-2987.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robertson G T, Elzer P H, Roop R M II. Vet Microbiol. 1996;49:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(96)84554-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips R W, Elzer P H, Roop R M II. Microb Pathog. 1995;19:227–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chatfield S, Strahan K, Pickard D, Charles I, Hormaeche C E, Dougan G. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:145–151. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cameron R M, Stevenson K, Inglis N F, Klausen J, Sharp J M. Microbiology. 1994;140:1977–1982. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gonzalez-Y-Merchand J A, Garcia M J, Gonzalez-Rico S, Colston M J, Cox R A. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6949–6958. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.6949-6958.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]