Abstract

The Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) mutant UV40 cell line is hypersensitive to UV and ionizing radiation, simple alkylating agents, and DNA cross-linking agents. The mutant cells also have a high level of spontaneous chromosomal aberrations and 3-fold elevated sister chromatid exchange. We cloned and sequenced a human cDNA, designated XRCC9, that partially corrected the hypersensitivity of UV40 to mitomycin C, cisplatin, ethyl methanesulfonate, UV, and γ-radiation. The spontaneous chromosomal aberrations in XRCC9 cDNA transformants were almost fully corrected whereas sister chromatid exchanges were unchanged. The XRCC9 genomic sequence was cloned and mapped to chromosome 9p13. The translated XRCC9 sequence of 622 amino acids has no similarity with known proteins. The 2.5-kb XRCC9 mRNA seen in the parental cells was undetectable in UV40 cells. The mRNA levels in testis were up to 10-fold higher compared with other human tissues and up to 100-fold higher compared with other baboon tissues. XRCC9 is a candidate tumor suppressor gene that might operate in a postreplication repair or a cell cycle checkpoint function.

Keywords: DNA repair, radiation sensitivity, chromosome aberrations, sister chromatid exchange

Ionizing radiation produces a complex mixture of strand breaks and base damage in DNA, and the repair pathways that act on this damage are not well understood in mammalian cells. Rodent cell mutants that are hypersensitive to ionizing radiation have been assigned to at least eight complementation groups (1–4). Human genes that correct these mutants have been given an XRCC designation (5). Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) EM9, which has 10-fold elevated sister chromatid exchange (SCE) and is hypersensitive to (m)ethylation damage and ionizing radiation, is complemented by the XRCC1 gene (6). The XRCC1 protein seems to be essential for normal base excision repair due to its interactions with DNA ligase III and polymerase β (7–9). Expression of mouse Xrcc1 is essential for early embryonic development (10). The XRCC2 and XRCC3 genes were recently isolated and shown to partially correct the various phenotypes of the respective mutants irs1 and irs1SF (11, 12).

Mutants in XRCC groups 4–7 exhibit high sensitivity (up to 6-fold) to ionizing radiation and show defects in rejoining DNA double-strand breaks (13–17) and in V(D)J recombination (18–20). XRCC4 was shown to function in both double-strand break rejoining and V(D)J recombination, and was suggested to participate in a postulated nonhomologous recombinational repair pathway (21). Studies with hybrid cells and cloned genes have shown the equivalence between genes encoding the Ku70/86 DNA-end binding autoantigen and its associated DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic (p460) subunit (DNA–PKcs) and those that are defective in mutant cells: XRCC5 (Ku86), XRCC6 (Ku70), and XRCC7 (SCID) (22–26). The Ku/DNA–PKcs pathway appears to account for rejoining of a substantial fraction of the double-strand breaks resulting from ionizing radiation and from gene rearrangement in germ-line lymphoid cells (27).

The CHO mutant UV40 represents a new complementation group that is unique among hamster cell mutants (28). UV40 exhibits hypersensitivity to multiple classes of mutagens and shows pronounced spontaneous chromosomal instability (≈25% abnormal metaphases). Isolated as being hypersensitive to UV (4-fold), UV40 cells seem to possess normal nucleotide excision repair and were reported to be hypersensitive to mitomycin C (MMC; 11-fold), ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS; 10-fold), methyl methanesulfonate (MMS; 5-fold), and ionizing radiation (2-fold) (28). UV40 is also unusual among rodent mutants in combining broad-spectrum sensitivity with a 3-fold elevated level of SCE. We report here the isolation of a human cDNA and genomic sequence, which efficiently corrects the chromosomal instability of UV40 and partially corrects mutagen sensitivity. We speculate that the product of the XRCC9 gene may participate in a postreplication repair pathway or a cell cycle checkpoint function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Cultures.

The CHO mutant line UV40TOR, derived from wild-type AA8 (28), was subcloned to obtain UV40TOR-1 (referred to simply as UV40 herein). Cell lines were grown in either monolayer or suspension culture in α-minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics as reported (6). The doubling times were ≈12 h for AA8 and ≈24 h for UV40. UV40 cells migrate and attach poorly to plastic surfaces, which prevents performing quantitative survival curves for colony-forming ability. Cellular toxicity was determined using a differential cytotoxicity assay in multi-well trays as reported (29). Cells (2 × 104) in 2 ml were plated in each well of a 12-well tray and incubated continuously at 37°C with various concentrations of MMC, EMS, or cisplatin (Sigma). Cells were fixed and stained after 4 days for AA8 and 7 days for the other cell lines.

DNA Transfection.

A human cDNA library in the vector pEBS7 (30) was kindly provided by Randy Legerski (University of Texas, Houston). UV40 (4 × 106 cells) in 10-cm dishes was exposed to 25 μg of DNA of the library fraction 2 (inserts size, 2–4 kb) in calcium phosphate precipitates for 24 h. After another 24-h expression in nonselective medium, cells were trypsinized and plated at 1 × 106 cells per 10-cm dish in 25 ml medium containing 70 nM MMC and 700 μg/ml hygromycin B (Calbiochem). Resistant colonies were isolated using Pipetman tips, expanded to mass culture, and checked for resistance to MMC. For the secondary transfection, high molecular weight genomic DNA was prepared from 1.6 × 108 cells of primary transformant 40T.1. DNA was isolated by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation at 26,000 rpm for 3 h at 20°C in Beckman L7–55 centrifuge with rotor SW28. Following dialysis against TE buffer (0.01 M Tris/0.001 M Na EDTA, pH 8.0), DNA was sheared four times with an 18.5-gauge needle and used to prepare precipitates. The DNA transfection and selection for a secondary transformant were the same as described for cDNA transfection. To produce cDNA transformants, the cloned cDNA in vector pcDNA3 (10 μg) was electroporated into 1 × 107 UV40 cells at 250 V/1600 μF. Cells were plated immediately at 1 × 106 cells per 10-cm dish and incubated in nonselective medium for 48 h, and then in medium containing 70 nM MMC and/or 1.6 mg/ml G418 (Sigma). Plasmid transformants in each 10-cm dish were pooled because the colonies merged with each other by cell migration. Single colonies were isolated from one of the transformant cell pools (40cXR9.3p). Transfection with 10 μg of a P1 genomic clone (≈80 kb insert) was done using calcium phosphate precipitation followed by selection in 70 nM MMC.

PCR Recovery of the cDNA.

The template DNA was prepared from the secondary transformant (40ST) by using a Qiagen (Chatsworth, CA) genomic DNA purification kit. Oligonucleotide primer 5′-CAACGGGACTTTCCAAAATGTC-3′ and nested primer 5′-AACAACTCCGCCCCATTGAC-3′ were designed complementary to pEBS7 vector 5′ flanking sequence and matched with primer 5′-GGAACCTTACTTCTGTGGTGTGACA-3′ for the 3′ flanking sequence. PCRs (100 μl) contained 0.2 μg of template DNA, 40 pmol each of the forward and reverse primers, 0.1 mM dNTP, 2.5 units of Pfu polymerase (Stratagene), and 1 × Opti-Prime buffer #6 (Stratagene). DNA was denatured at 94°C for 2 min, annealed at 60°C for 1 min, and extended at 75°C for 3 min for the first cycle, followed by 30 cycles with denaturing at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 58°C for 1 min, and extension at 75°C for 3 min. The PCR product was purified using a gel extraction kit (Qiagen), cloned into the pCRScript vector (Stratagene), and sequenced using conventional fluorescence dideoxy chemistry on a model 377 Applied Biosystems sequencer.

Northern Hybridization.

A 1.5-kb HindIII/BamHI fragment of XRCC9 cDNA (see details in Fig. 5) was used as a probe against hamster mRNA. Four micrograms of poly(A)+ RNA isolated from AA8, UV40, and HeLa cells was separated on a formamide denaturing agarose gel and transferred to Hybond nylon membrane (Amersham). The blot was hybridized overnight at 55°C with 32P-labeled XRCC9 probe in Church–Gilbert buffer (0.5 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.4/7% SDS/0.001 M EDTA/1% BSA). The blot was washed to a stringency of 0.5× SSC (SSC = 0.15 M NaCl/0.015 M sodium citrate) plus 0.1% SDS at 55°C and 0.1× SSC plus 0.1% SDS at room temperature. A human tissue Northern blot (CLONTECH) containing ≈2 μg poly(A)+ RNA per lane was hybridized at 65°C with the same probe and washed to a stringency of 1× SSC at 65°C. Blots were stripped and reprobed with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) or actin cDNA, respectively. A Molecular Dynamics Storm 860 PhosphorImager was used to analyze the human Northern blot, and quantitation was performed using imagequant software. The baboon tissue blot containing 10 μg mRNA per lane was probed with the 1.5-kb XRCC9 fragment and subsequently with GAPDH cDNA and analyzed as described (31).

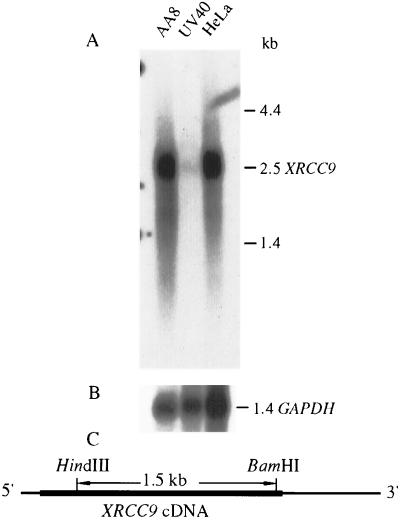

Figure 5.

Northern blots of hamster and human poly(A)+ RNA. Four micrograms of poly(A)+ RNA from each cell line was loaded per lane and probed with a 1.5-kb XRCC9 cDNA fragment (A) and subsequently with GAPDH cDNA (B). The film was exposed for 16 h or 1 h for A and B, respectively. (C) Location within the cDNA of the 1.5-kb fragment used in hybridization. The ORF is shown by the bold line.

Chromosome Mapping by Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization (FISH).

Human XRCC9 genomic DNA P1 clone (DMPC-HFF #1-305-B12) obtained from Genome Systems (St. Louis) was used as the probe. One microgram of DNA in 100 μl of water was treated (for 1.5 h in a water-bath cleaner sonicator) to produce fragments of ≈500 bp. A total of 290 ng of DNA was labeled using the Prime-it fluor fluorescence kit (Stratagene), which incorporates fluorescein-conjugated dUTP into DNA. Hybridizations were performed by combining 2 μl of labeled DNA (≈11 ng) with 1.5 μl of 1 mg/ml human Cot 1 DNA (GIBCO/BRL), 1 μl sterile water, and 10.5 μl of hybridization mix (32, 33). The probe and target material were denatured for 5 min at 70°C; the probe mixture was placed on a slide and sealed under a coverslip with rubber cement and incubated at 37°C for ≈40 h. Unbound probe was removed as described (32, 33). Slides were mounted with propidium iodide/4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)/antifade and viewed with a Zeiss epifluorescence microscope equipped with appropriate filters (DAPI is from Sigma). Photography was performed with Kodak Ektachrome 400 Elite color slide film. Localization of XRCC9 to 9p13 was performed by DAPI–actinomycin D banding as described (34).

Chromosomal Aberrations and SCE.

Suspension cultures were initiated at 1 × 105 cells/ml with 10 μM BrdUrd (for SCE) or without BrdUrd (for chromosomal aberrations). Incubation was carried out at 37°C for 24 h for the parental AA8 cells, and 42 h for the mutant and the transformants before adding Colcemid at 0.1 μg/ml. After 4 h cells were harvested and prepared for aberration and SCE analysis as described (35).

RESULTS

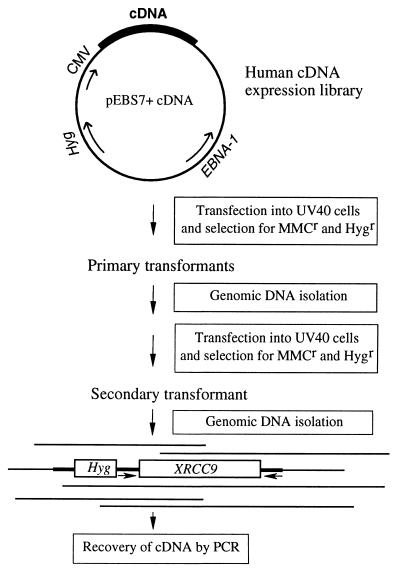

Cloning of XRCC9 cDNA by Functional Complementation.

The cloning procedure is outlined in Fig. 1. Preliminary tests showed that UV40 cells were completely killed by 70 nM MMC, a concentration that was nontoxic to wild-type AA8. DNA transfection efficiency with calcium phosphate precipitates was measured by the frequency of hygromycin-resistant colonies and was determined as 1.5 × 10−3 per viable cell. From 8.7 × 107 UV40 cells transfected with the pEBS7 cDNA library, five primary transformants that were resistant to both hygromycin and 70 nM MMC were isolated. All these clones (40T.1–40T.5) were shown to be cross-resistant to EMS by the differential cytotoxicity assay (see example below in Fig. 4), suggesting that resistance did not arise from altered MMC metabolism. Because vector pEBS7 carries the EBNA-1 gene, which may allow episomal replication, Hirt extracts (36) were made from the primary transformants and used to transfect Escherichia coli. No bacterial transformants were obtained, indicating that the correcting cDNA was integrated into the genome. Genomic DNA was then isolated from the primary transformant 40T.1 and used in a secondary transfection. Only one secondary transformant colony (40ST) was obtained from 2.6 × 108 transfected cells.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of cloning strategy. The primers used for amplifying the XRCC9 cDNA by PCR are indicated by arrows.

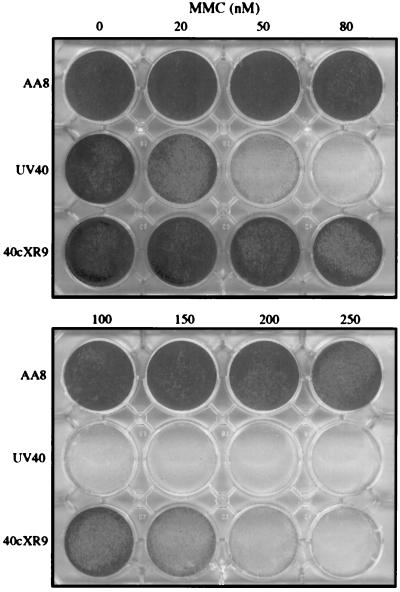

Figure 4.

Differential cytotoxicity to MMC of wild-type AA8, mutant UV40, and cDNA transformant 40cXR9.31. Cells (2 × 104) were inoculated in 12-well trays and incubated with MMC for 4 days (AA8) or 7 days (UV40 and 40cXR9.31) before fixation. Trays were stained with crystal violet.

To recover the cDNA, genomic DNA was isolated from transformant 40ST, and PCR was performed using vector-specific primers. A 2.8-kb PCR product was obtained from both 40T.1 and 40ST DNAs but not from UV40 DNA. This DNA product was blunt-end ligated into the SfrI sites of the pCRscript vector and then subcloned into pcDNA3, resulting in plasmid pcDNA3/2.8k. Electroporation of pcDNA3/2.8k into UV40 cells conferred resistance to MMC (described below), and several cDNA transformants (clonal isolates designated 40cXR9.31, -32, etc.) were obtained.

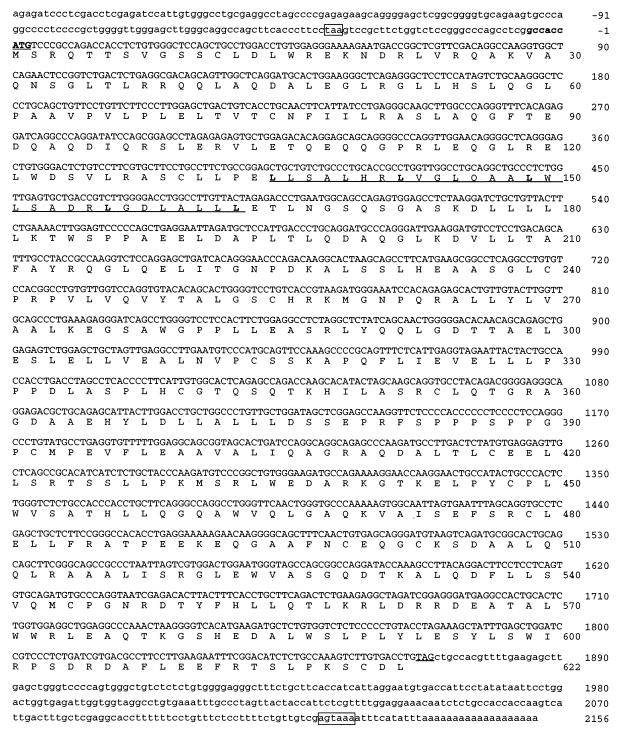

XRCC9 cDNA Sequence.

The nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequences of the XRCC9 cDNA are shown in Fig. 2. The cDNA contained an 1866 bp ORF, encoding 622 amino acids. A putative translation initiation site appeared at ≈180 bp from the 5′ end closely resembling the consensus sequence (GCCACCatgG) (37). The 5′ untranslated region was rich in GC (68%), which is characteristic of house-keeping genes (37). A leucine-zipper motif (38) was found in the amino-terminal region (residues 135–163, underlined in Fig. 2). Computer modeling revealed an amphipathic helix structure in this region (results not shown). A putative poly(A) signal (AGTAAA) (39) appeared 11 bp upstream of the poly(A) addition site (boxed in Fig. 2). Database searching for homologs showed that translated XRCC9 gene was novel, having no significant similarity with any known protein.

Figure 2.

Nucleotide sequence of XRCC9 cDNA and the translated amino acid sequence. The consensus translation initiation sequence is indicated in bold. The start and stop codons and a leucine zipper region are underlined. An in-frame stop codon (taa) upstream of the ATG start codon and the polyadenylation signal (agtaaa) upstream of the polyadenylation site are boxed.

Chromosomal Localization of XRCC9.

To localize the XRCC9 gene by FISH, human XRCC9 genomic DNA was isolated by screening a P1 DNA library in vector pAD10SacBII (done by Genome Systems) using the HindIII/BamHI cDNA fragment (see Fig. 5C) as the probe. Fluorescein-labeled XRCC9 P1 clone DNA exhibited clear hybridization signals on chromosome 9p as identified by DAPI/propidium iodide counterstaining (Fig. 3). Detailed localization of the signal to 9p13 was determined by DAPI–actinomycin D banding (results not shown).

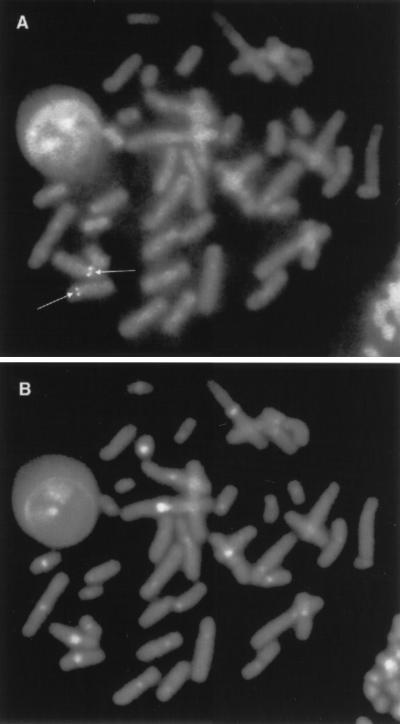

Figure 3.

Human chromosomal localization of XRCC9. (A) FISH image of a human metaphase cell showing hybridization of the genomic probe to chromosome 9p13. (B) DAPI staining of the same metaphase showing bright staining of the centromeric region of a C-group chromosome, which is diagnostic of chromosome 9.

Correction of the Mutagen Sensitivity and Chromosomal Instability in UV40 Cells.

Sensitivity of the XRCC9 transformants to several mutagens was determined by the differential cytotoxicity assay. Fig. 4 shows a typical experiment in which the cDNA plasmid transformant 40cXR9.31 exhibited partial correction of the hypersensitivity of UV40 to MMC when compared with the wild-type AA8. Similar correction was seen with the primary and secondary transformants and a genomic transformant (Table 1). The sensitivity of UV40 to cisplatin, another cross-linking agent, was ≈4-fold, and cDNA transformants showed partial correction for this mutagen as well as for EMS and UV radiation. In this assay, the genomic transformant (40XR9GT) showed nearly full correction for cisplatin. Both cDNA and genomic transformants exhibited only slightly increased resistance (≈1.2-fold) to 137Cs γ-rays compared with UV40, which was difficult to measure because the effect was small and the mutant is only 2-fold hypersensitive.

Table 1.

Lowest effective concentration (LEC) of mutagens for killing wild-type, UV40, and XRCC9 transformants

| Cell line | MMC

|

Cisplatin

|

EMS

|

UV

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEC, nM | Correction, % | LEC, μM | Correction, % | LEC, μg/ml | Correction, % | LEC, J/m2 | Correction, % | |

| AA8 (wild type) | 650 | 100 | 5 | 100 | 600 | 100 | 30 | 100 |

| UV40 | 50 | 0 | 1.4 | 0 | 150 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| 40T.1 | 200 | 25 | 3 | 44 | 300 | 33 | 25 | 64 |

| 40ST | 200 | 25 | ND | — | 250 | 22 | ND | — |

| 40cXR9.31 | 250 | 33 | 3 | 44 | 250 | 22 | 25 | 64 |

| 40cXR9.32 | 250 | 33 | ND | — | ND | — | ND | — |

| 40XR9GT | 200 | 25 | 5 | 100 | ND | — | ND | — |

LEC = lowest effective concentration (or UV fluence) that kills >90% of the cells. Percent correction = [LEC(transformant) − LEC(mutant)] ÷ [LEC(wild type) − LEC(mutant)] × 100%. ND = not determined.

The elevated frequency of spontaneous chromosomal aberrations in UV40 cells was efficiently corrected in the XRCC9 transformants (Table 2), ranging from 92% for the primary transformant to 100% for the secondary and cDNA plasmid transformants. However, the high baseline level of SCE per cell found in UV40 cells [20.8 ± 0.7 (SEM) vs. 7.2 ± 0.4 for AA8 cells) was not significantly reduced in three transformants, which ranged from 19.8 ± 1.7 to 27.8 ± 0.7.

Table 2.

Frequency of spontaneous aberrations in wild-type, mutant, and XRCC9 transformants

| Cell line | Abnormal cells,* % | Chromatid

|

Chromosome

|

Gaps‡ | Total aberrations§ | Correction, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breaks | Exchanges | Breaks | Exchanges† | |||||

| Wild-type AA8 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 5 | — |

| UV40 | 28 | 33 | 16 | 15 | 6 | 12 | 70 | — |

| 40T.1 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 2¶ | 2 | 11 | 10 | 92 |

| 40ST | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 100 |

| 40cXR9.31 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 100 |

One hundred cells were scored for each cell line.

Including dicentrics and rings.

Including chromosome and chromatid gaps.

Excluding all gaps.

Thirty-two cells exhibited a break in the middle of the long arm of chromosome 1. These apparently identical aberrations, which appeared similar to fragile sites, were excluded from the analysis because they were not random and their biological significance is unclear.

Reduced Level of XRCC9 mRNA Expression in UV40 Cells.

To investigate potential alternations of the hamster XRCC9 gene, we used an XRCC9 cDNA fragment to probe UV40 and parental mRNA by Northern blot analysis. UV40 cells showed almost no hybridization signal for the 2.5-kb XRCC9 mRNA band that is present in AA8 cells and HeLa cells (Fig. 5). This result suggests that both alleles of the XRCC9 gene are altered in UV40 cells.

Differential Expression of XRCC9 in Human and Baboon Tissues.

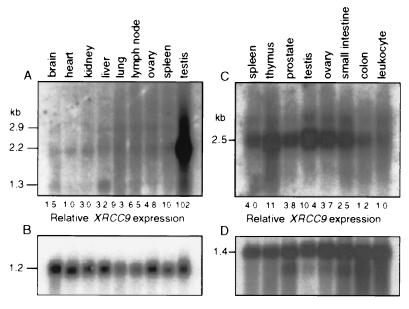

Major mRNA bands of 2.2 kb and 2.5 kb were detected on baboon and human Northern blots, respectively (Fig. 6). In baboon, the expression was 10- to 100-fold higher in testis than in the other tissues (Fig. 6A). In human tissues, XRCC9 mRNA levels were highest in testis and thymus, by a factor of 10 compared with the level in peripheral blood leukocytes (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Northern blots of poly(A)+ RNA showing relative XRCC9 mRNA expression in tissues of baboon and human. Baboon RNAs were probed with XRCC9 (A) or GAPDH (B) cDNA. Lanes: 1, brain; 2, heart; 3, kidney; 4 liver; 5, lung; 6, lymph node; 7, ovary; 8, spleen; 9, testis. Human RNAs were probed with XRCC9 (C) or actin (D) cDNA. Lanes: 1, spleen; 2, thymus; 3, prostate; 4, testis; 5, ovary; 6, small intestine; 7, colon (mucosal lining); 8, peripheral blood leukocyte. XRCC9 signals were normalized to reference RNAs as shown using cpm.

DISCUSSION

We have identified a human cDNA and gene, designated XRCC9, which partially or completely corrected several of the defects of CHO mutant UV40. The mutation(s) in UV40 results in little or no expression of the XRCC9 gene. Whereas the cDNA was isolated based on its ability to confer MMC resistance, it also conferred partial resistance to UV radiation, EMS, and cisplatin (Table 1). The XRCC9 cDNA seems to contain a complete ORF based on our analysis. The size of the human mRNA (2.5 kb) is reasonably consistent with that of the cDNA insert (2.15 kb) if one allows for a poly(A) tail and additional 5′ untranslated sequence. Partial correction in hamster mutants by human repair genes also occurred with XRCC3 (11), XRCC4 (40), and XPF (31) and probably results from interspecies differences between proteins. Although γ-ray sensitivity appeared to be slightly corrected in the transformants, the differences in growth rate of AA8, UV40, and transformants are confounding variables. Thus, the physiological significance of a small degree of increased resistance is unclear. Cloning of hamster XRCC9 and constructing a knockout mutant would provide a means to clearly address the role of XRCC9 in γ-ray sensitivity.

XRCC9 encodes a protein having no homology with any other polypeptide sequence in the databases, and it is not possible to assign XRCC9 to a known DNA repair pathway. Although UV40 has enhanced sensitivity to killing and inhibition of DNA synthesis by UV irradiation, it has normal removal of 6-4 photoproducts and near-normal incision kinetics at early times after UV exposure (28). The UV inhibition kinetics of RNA synthesis are also essentially normal, suggesting intact preferential repair of active genes (28). The phenotype of UV40 in terms of its broad sensitivity to diverse DNA lesions resembles that of certain mutants in the RAD6 epistasis group of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In particular, rad6 and rad18 mutants display prominent sensitivity to a wide variety of DNA damaging agents, including UV radiation, ionizing radiation, and alkylating agents (40–42). rad6 and rad18 mutants are defective in postreplication repair (43, 44), a process that overcomes the blockage of nascent strand elongation at sites of damage. So far, no human genes analogous to the RAD6 epistasis group have been identified, and XRCC9 should be considered a candidate.

Furthermore, the abnormally sensitive inhibition of DNA replication by UV radiation in UV40 (28) implies a substantial damage-induced block to DNA replication, a phenomenon found in the xeroderma pigmentosum variant (45–49). The CHO mutant UV-1 was also characterized as being defective in postreplication repair after UV irradiation (50). UV-1 resembles UV40 in having increased sensitivity of DNA synthesis to UV irradiation (51) and in being cross-sensitive to other DNA damaging agents, especially methylating and cross-linking agents (52), but it differs from UV40 in apparently having normal chromosome stability (C. Waldren, personal communication).

Alternatively, XRCC9 may play a role analogous to the rad9+ gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe (53) and the (structurally unrelated) RAD9 gene of S. cerevisiae (54), which are involved in regulating cell cycle progression in response to both ionizing and ultraviolet radiation. The slow growth of UV40 is associated with an altered cell cycle distribution (increased percentages of cells in G1 and G2; N.L. and L.H.T., unpublished results). XRCC9 cDNA and genomic transformants showed ≈10% decrease in the doubling time. Again, an independent mutant is needed to assess the significance of altered cell cycle parameters.

Several human genes that are essential for chromosome stability have been isolated, and they encode diverse, poorly understood functions: ATM (ataxia telangiectasia) (55), BLM (Bloom syndrome) (56), FAA and FAC (Fanconi anemia complementation groups A and C) (57, 58), and XRCC3 (11). Mutations in these genes have widely differing physiological consequences. XRCC9 represents another gene that may eventually lead to an understanding of the origin of both spontaneous and induced chromosomal aberrations. Chromatid aberrations may arise from gaps in daughter DNA strands. Such single-stranded regions are hypothesized targets for endonuclease activity, resulting in the formation of double-strand breaks, which are seen at metaphase as chromatid breaks (59). Chromatid exchanges result from the rejoining of double-strand breaks on different chromatids, and MMC induces extremely high levels of chromatid breaks and exchanges in UV40 cells in addition to the already high baseline (28).

Despite the efficient correction for chromosomal aberrations in XRCC9 transformants, they retained high SCE levels like UV40. Excess SCEs may be associated with the incorporated BrdUrd normally used in the assay. The failure to see correction for SCE could be due to a secondary mutation in UV40 unrelated to XRCC9, such as one that alters the efficiency of incorporation of BrdUrd into DNA.

XRCC9 was mapped to human chromosome 9p13. Recently this chromosomal region was reported to show loss of heterozygosity in about 50% of tumor samples from small cell lung cancer (60). Therefore, XRCC9 should be examined as a candidate tumor suppressor gene for this, and possibly other types of, cancer. Clues about the biochemical role of XRCC9 protein may be obtained by identifying proteins that interact with it, as well as characterizing in detail the phenotype of mutant cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Aaron Adamson for assistance with nucleotide sequence determination, Jane Briner for assistance with the scoring of chromosome aberrations and SCE, Marilyn Ramsey for assistance with the FISH, Wufang Fan for assistance with Northern blot analyses, Krzysztof Fidelis for assistance with protein structure prediction, and Kerry Brookman and Ian McConnell for valuable discussions. This work was done under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under Contract W-7405-ENG-48, and the research was funded partly by National Institutes of Health Grants GM32833 and CA34936.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: SCE, sister chromatid exchange; MMC, mitomycin C; EMS, ethyl methanesulfonate; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. U70310).

References

- 1.Jeggo P A, Tesmer J, Chen D J. Mutat Res. 1991;254:125–133. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(91)90003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thacker J, Wilkinson R E. Mutat Res. 1991;254:135–142. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(91)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins A R. Mutat Res. 1993;293:99–118. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(93)90062-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zdzienicka M Z. Mutat Res. 1995;336:203–213. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(95)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson L H, Jeggo P A. Mutat Res. 1995;337:131–134. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(95)00018-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson L H, Brookman K W, Jones N J, Allen S A, Carrano A V. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6160–6171. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caldecott K W, McKeown C K, Tucker J D, Ljungquist S, Thompson L H. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:68–76. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caldecott K W, McKeown C K, Tucker J D, Stanker L, Thompson L H. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4836–4843. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.23.4836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caldecott K W, Aoufouchi S, Johnson P, Shall S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4387–4394. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tebbs, R. S., Meneses, J. J., Pedersen, R. A., Thompson, L. H. & Cleaver, J. E. (1996) Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 27 (Suppl. 27), 68 (abstr.).

- 11.Liu N, Lamerdin J E, Siciliano M J, Carrano A V, Thompson L H. Am J Hum Genet Suppl. 1995;57:A147. (abstr.). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tebbs R S, Zhao Y, Tucker J D, Scheerer J B, Siciliano M J, Hwang M, Liu N, Legerski R J, Thompson L H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6354–6358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemp L M, Sedgwick S G, Jeggo P. Mutat Res. 1984;132:189–196. doi: 10.1016/0167-8817(84)90037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giaccia R, Weinstein R, Hu J, Stamato T D. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1985;11:485–491. doi: 10.1007/BF01534842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitmore G F, Varghese A J, Gulyas S. Int J Radiat Biol. 1989;56:657–665. doi: 10.1080/09553008914551881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biedermann K A, Sun J R, Giaccia A J, Tosto L M, Brown J M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1394–1397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang C, Biedermann K A, Mezzina M, Brown J M. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1244–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taccioli G E, Rathbun G, Oltz E, Stamato T, Jeggo P A, Alt F W. Science. 1993;260:207–210. doi: 10.1126/science.8469973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taccioli G E, Gottlieb T M, Blunt T, Priestley A, Demengeot J, Mizuta R, Lehmann A R, Alt F W, Jackson S P, Jeggo P A. Science. 1994;265:1442–1445. doi: 10.1126/science.8073286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieber M R, Hesse J E, Lewis S, Bosma G C, Rosenberg N, Mizuuchi K, Bosma M J, Gellert M. Cell. 1988;55:7–16. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z, Otevrel T, Gao Y, Cheng H L, Seed B, Stamato T D, Taccioli G E, Alt F W. Cell. 1995;83:1079–1089. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smider V, Rathmell W K, Lieber M R, Chu G. Science. 1994;266:288–291. doi: 10.1126/science.7939667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taccioli G E, Cheng H L, Varghese A J, Whitmore G, Alt F W. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7439–7442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boubnov N V, Hall K T, Wills Z, Lee S E, He D M, Benjamin D M, Pulaski C R, Band H, Reeves W, Hendrickson E A, Weaver D E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:890–894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blunt T, Finnie N J, Taccioli G E, Smith G C, Demengeot J, Gottlieb T M, Mizuta R, Varghese A J, Alt F W, Jeggo P A, Jackson S P. Cell. 1995;80:813–823. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirchgessner C U, Patil C K, Evans J W, Cuomo C A, Fried L M, Carter T, Oettinger M A, Brown J M. Science. 1995;267:1178–1183. doi: 10.1126/science.7855601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeggo P A, Taccioli G E, Jackson S P. BioEssays. 1995;17:949–957. doi: 10.1002/bies.950171108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busch D B, Zdzienicka M Z, Natarajan A T, Jones N J, Overkamp W I J, Collins A, Mitchell D L, Stefanini M, Botta E, Riboni R, Albert R B, Liu N, Thompson L H. Mutat Res. 1996;363:209–221. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(96)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoy C A, Salazar E P, Thompson L H. Mutat Res. 1984;130:321–332. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(84)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Legerski R, Peterson C. Nature (London) 1992;359:70–73. doi: 10.1038/359070a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brookman K W, Lamerdin J E, Thelen M P, Hwang M, Reardon J T, Sancar A, Zhou Z Q, Walter C A, Parris C N, Thompson L H. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6553–6562. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinkel D, Landegent J, Collins C, Fuscoe J, Segraves R, Lucas J, Gray J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9138–9142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tucker J D, Breneman J W, Lee D A, Ramsey M J, Swiger R R. In: Cell Biology: A Laboratory Handbook. Celis J E, editor. Orlando, FL: Academic; 1994. pp. 450–458. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tucker J D, Christensen M L, Carrano A V. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1988;48:103–106. doi: 10.1159/000132600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carrano A V, Minkler J L, Dillehay L E, Thompson L H. Mutat Res. 1986;162:233–239. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(86)90090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirt B. J Mol Biol. 1967;26:365–369. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kozak M. Mamm Genome. 1996;7:563–574. doi: 10.1007/s003359900171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Landschulz W H, Johnson P F, McKnight S L. Science. 1988;240:1759–1763. doi: 10.1126/science.3289117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birnstiel M L, Busslinger M, Strub K. Cell. 1985;41:349–359. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prakash L. Genetics. 1974;78:1101–1118. doi: 10.1093/genetics/78.4.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prakash L. Genetics. 1976;83:285–301. doi: 10.1093/genetics/83.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prakash S, Sung P, Prakash L. Annu Rev Genet. 1993;27:33–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.27.120193.000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prakash L. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;184:471–478. doi: 10.1007/BF00352525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawrence C. BioEssays. 1994;16:253–258. doi: 10.1002/bies.950160408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lehmann A R, Kirk-Bell S, Arlett C F, Paterson M C, Lohman P M H, De Weerd-Kastelein E A, Bootsma D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:219–223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.1.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park S D, Cleaver J E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:3927–3931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.8.3927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boyer J C, Kaufmann W K, Brylawski B P, Cordeiro-Stone M. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2593–2598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griffiths T D, Ling S Y. Mutagenesis. 1991;6:247–251. doi: 10.1093/mutage/6.4.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Misra R R, Vos J M H. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:1002–1012. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stamato T D, Hinkle L, Collins A R S, Waldren C A. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1981;7:307–320. doi: 10.1007/BF01538856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collins A, Waldren C. J Cell Sci. 1982;57:261–275. doi: 10.1242/jcs.57.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoy C A, Thompson L H, Salazar E P, Steward S A. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 1985;11:523–532. doi: 10.1007/BF01534718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lieberman H B, Hopkins K M, Laverty M, Chu H M. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;232:367–376. doi: 10.1007/BF00266239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weinert T A, Hartwell L H. Genetics. 1993;134:63–80. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Savitsky K, Bar-Shira A, Gilad S, Rotman G, Ziv Y, et al. Science. 1995;268:1749–1753. doi: 10.1126/science.7792600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ellis N A, Groden J, Ye T Z, Straughen J, Lennon D J, Ciocci S, Proytcheva M, German J. Cell. 1995;83:655–666. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strathdee C A, Gavish H, Shannon W R, Buchwald M. Nature (London) 1992;356:763–767. doi: 10.1038/356763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lo Ten Foe J R, Rooimans M A, Bosnoyan-Collins L, Alon N, Wijker M, et al. Nat Genet. 1996;14:320–323. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaufmann W K. Carcinogenesis. 1989;10:1–11. doi: 10.1093/carcin/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim S K, Ro J Y, Kemp B L, Lee J S, Kwon T J, Fong K M, Sekido Y, Minna J D, Mong W K, Mao L. Cancer Res. 1997;57:400–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]