Abstract

A single-chain Fv (scFv) fusion phage library derived from random combinations of VH and VL (variable heavy and light chains) domains in the antibody repertoire of a vaccinated melanoma patient was previously used to isolate clones that bind specifically to melanoma cells. An unexpected finding was that one of the clones encoded a truncated scFv molecule with most of the VL domain deleted, indicating that a VH domain alone can exhibit tumor-specific binding. In this report a VH fusion phage library containing VH domains unassociated with VL domains was compared with a scFv fusion phage library as a source of melanoma-specific clones; both libraries contained the same VH domains from the vaccinated melanoma patient. The results demonstrate that the clones can be isolated from both libraries, and that both libraries should be used to optimize the chance of isolating clones binding to different epitopes. Although this strategy has been tested only for melanoma, it is also applicable to other cancers. Because of their small size, human origin and specificity for cell surface tumor antigens, the VH and scFv molecules have significant advantages as tumor-targeting molecules for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and can also serve as probes for identifying the cognate tumor antigens.

In earlier reports (1, 2) we described the isolation of the melanoma-specific clone V86 from a single-chain Fv (scFv) fusion phage library derived from the antibody repertoire of melanoma patient DM414, who was vaccinated with autologous tumor cells transfected with the interferon-γ gene and showed an induced humoral response to the tumor (Z. Abdel-Wahab, C. Weltz, B. S. Hester, N. Pickett, C. Vervaert, D. Jolly, J. R. Barger, and H. F. Seigler, personal communication). Although isolated from a scFv library, V86 does not contain the expected light chain variable domain (VL) because an extraneous cloning site located near the 5′ end of the VL cDNA was cleaved during construction of the library, resulting in a deletion of the distal VL region. Therefore V86 is essentially a VH fusion phage. When different VL domains from patient DM414 were conjugated to V86 to form complete scFv fusion phage, most of the VL domains inhibited binding to melanoma cells. This finding suggests that tumor-specific heavy chain variable domains (VH) might remain undetected in a scFv library because the VH and VL domains are randomly paired and most VL partners would probably be functionally incompatible; the compatible combinations might not be represented in a scFv library of average size, which can encompass only a small fraction of the possible random combinations of VH and VL domains. This problem could be circumvented with a VH library displaying VH domains unassociated with VL domains; such a library could encompass virtually all of the different VH domains in a person’s B cells. In this report we have compared a VH library with a matched scFv library as a source of melanoma-specific clones. Each library contained the same VH domains derived from the peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL) cells of patient DM414. The results demonstrate that melanoma-specific VH and scFv clones with different VH domains can be isolated from the two libraries, providing evidence that both VH and scFv fusion phage libraries derived from the antibody repertoire of a vaccinated cancer patient can serve as a source of tumor-specific clones.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultured Cells and Frozen Tissue Sections.

Primary cultures of human melanocyte and fibroblast cells from foreskins, and endothelial cells from umbilical cords, were obtained from the Cell Culture Core Service of the Yale Skin Disease Research Center and the Yale Endothelial Cell Culture Facility, respectively. Established lines of melanoma and other human tumor cells were obtained from the laboratory of Hilliard Seigler (Duke University Medical Center), the Yale Skin Disease Research Center, and the American Type Culture Collection. The cell lines were grown in DMEM/10% fetal calf serum (FCS) medium. Frozen sections of tumor and normal human tissues were obtained from the Yale Critical Technologies Facility.

Construction of scFv and VH Fusion Phage Libraries.

The scFv library was constructed as described (1, 2). The VH and VL cDNAs for this library were synthesized using poly(A)+ RNA isolated from the PBL of melanoma patient DM414 who was vaccinated with autologous tumor cells transfected with interferon-γ cDNA (Abdel-Wahab et al., personal communication). For the VH library the same poly(A)+ RNA sample was used to synthesize the VH cDNAs, as follows. First-strand cDNAs were synthesized using random hexamers and oligo(dT) primers. The coding region for the VH domain of the heavy chain was amplified by PCR using the primers shown in Fig. 1. Each PCR mixture contained 2 μl of the first-strand cDNA preparation, 50 pm of a constant-region forward-primer, 50 pm of a back-primer, 250 nm dNTPs, and 2.5 units of Taq polymerase in buffer as provided (Boehringer Mannheim). The “touchdown” PCR protocol consisted of three cycles each of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing for 2 min, and elongation at 74°C for 3 min; the annealing temperature was varied from 55°C to 46°C in steps of 1°C. The touchdown cycles were followed with 10 cycles of annealing at a temperature of 45°C and a 10-min extension at 74°C. The PCR product was purified by electrophoresis in 1% low-melting agarose gel and extraction from the gel using β-agarose (New England Biolabs); the purified DNA was dissolved in 40 μl TE buffer.

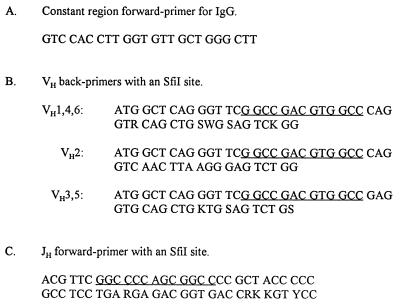

Figure 1.

PCR primers for constructing a VH fusion phage library. The direction of the primer sequences is 5′ to 3′. Forward primers are complementary to the sense strand, and back primers are complementary to the antisense strand. The symbols for degenerate nucleotides are as follows: Y = C or T; R = A or G; W = A or T; S = C or G; K = T or G; M = A or C. The SfiI sites are underlined,

For the next step two sets of PCR primers were used: One was the joining-region heavy chain forward primer with an SfiI site (Fig. 1C) used in combination with the VH back primers (Fig. 1B). The PCR reagents and conditions were the same as above, except that the primer concentration was 10 pm and the reaction involved 30 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min followed by extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were purified as described above.

The VH cDNAs and the replicative form of the DNA for the fUSE5 vector phage (3) were digested with SfiI and purified by electrophoresis in 1% low-melting agarose gel. The cDNAs were ligated to the vector DNA in 100 μl of reaction mixture containing 0.8 μg cDNA, 8 μg vector DNA, and 2,000 units T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) for 16 hr at 16°C. The ligation product was purified by extraction with phenol/chloroform and precipitation with ethanol, and the precipitate was dissolved in 20 μl of water. The purified DNA sample was used to transform DH10B ElectroMax cells (GIBCO/BRL), and the cells were plated on 2× TY agar medium containing 12.5 μg/ml tetracycline (2× TY tet agar). The number of transformed colonies collected for both the VH and scFv libraries was about 3 × 108.

The fUSE5 phage vector(4) used for constructing both the VH and scFv libraries contains the complete phage genome; therefore each fusion phage in the library will display the encoded VH or scFv molecule on all of its gene-3 proteins.

Panning the VH and scFv Libraries.

The melanoma cell line A2058 was grown as an attached monolayer in 24-cm2 flasks until almost confluent, washed with PBS, and fixed with 0.24% glutaraldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. The fixed cells were washed with PBS and blocked with DMEM/10% FCS for 1 hr at room temperature. The phage from the VH and scFv libraries were precipitated with 4% PEG/0.5 M NaCl and resuspended in water, and about 1013 phage in 2 ml of DMEM/10% FCS were added to the melanoma cells. The culture flask was shaken gently for 2 hr at room temperature and the medium removed, and the cells were washed rapidly 10 times with PBS at room temperature. The attached phage were eluted in 2 ml E-buffer for 10 min at room temperature and immediately neutralized with 0.375 ml N-buffer (3). The eluted phage were mixed with 15 ml of an Escherichia coli K91 KanR cells, and after 30 min at room temperature the cells were plated on 2× TY tet agar and incubated overnight at 37°C. The resulting colonies were collected in 50 ml of 2× TY tet medium and incubated at 37°C for 1 hr, and the bacteria were pelleted. The supernatant medium containing phage was filtered through a 0.45-micron membrane. For each subsequent panning step the phage from the previous panning step were precipitated in 4% PEG/0.5 NaCl and resuspended in water, and about 1011 transforming units of the phage were used for panning against melanoma cells A2058 as described above for the first panning step.

Absorption Against Normal Fibroblast Cells.

The cells were grown to confluence in 35-mm culture dishes, fixed with 0.25% glutaraldehyde for 10 min, and blocked with DMEM/10% FCS. The phage recovered from the last panning step were added to the cells for 1 hr at room temperature. The unabsorbed phage were transferred to a fresh culture dish containing fixed fibroblasts; the procedure was repeated 10 times.

Preparation of Fusion Phage Clones.

E. coli K91 KanR cells were infected with phage at a low phage to cell ratio, incubated at room temperature for 20 min, and plated on 2× TY tet agar. The plates were incubated overnight at 37°C. Individual colonies were inoculated into 2 ml of 2× TY tet medium and incubated for 24 hr at 37°C with shaking. The cells were pelleted and the medium containing the phage was filtered through a 0.45 micron membrane and stored at 4°C.

Restriction Analysis of VH and scFv cDNAs in Fusion Phage.

The cDNAs were synthesized by PCR using primers that hybridize to phage sequences flanking the cDNAs (2). The PCR products were digested separately with AluI, DdeI, HaeIII, and RsaI, and the digests were analyzed by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel.

ELISA Tests for Fusion Phage Binding to Cells.

The ELISA procedure involves growing cells in 96-well plates, fixing the cells with glutaraldehyde, adding the phage sample, and determining the amount of bound phage with an anti-M13/HRP (horseradish peroxidase) antibody conjugate (Pharmacia) and o-phenylenediamine substrate (1).

Immunohistochemistry.

Cultured cells. The cells were grown to confluence in 16-well chamber slides (Nunc), washed with PBS, fixed with 0.24% glutaraldehyde/PBS for 15 min at room temperature, and blocked with DMEM/10% FCS. The fusion phage clone for the reaction was diluted 1:1 with the blocking solution and 250 μl was added to the cells for 2 hr at room temperature. The cells were washed three times with PBS, and 150 μl of anti-M13/HRP antibody conjugate diluted 1:100 with the blocking solution was added for 1 hr at room temperature followed by three washes with PBS. The substrate for HRP (VIP from Vector Laboratories) was added for 10 min at room temperature, and the cells were washed with PBS and water, counterstained with methyl green, and mounted.

Frozen sections.

Four-micron sections were cut from frozen tissue, attached to slides, and stored at −70°C until used. The sections were fixed for immunohistochemistry and reacted with fusion phage clones, and the bound phage was visualized as described above for cultured cells.

RESULTS

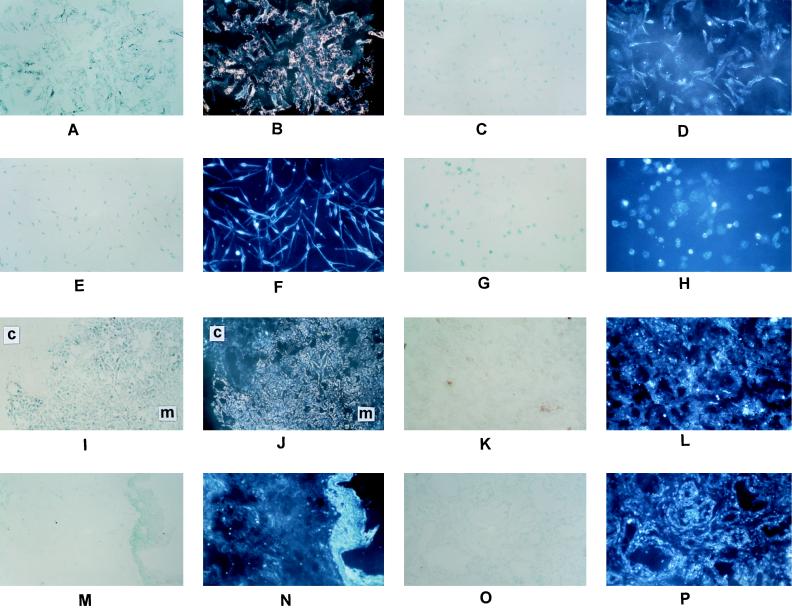

The protocol for panning and characterizing melanoma-specific clones from the VH and scFv fusion phage libraries is shown in Tables 1 and 2. Both the VH and scFv cDNAs for the libraries were derived from the antibody mRNAs in the PBL of patient DM414 (Abdel-Wahab et al., personal communication). The two libraries were panned twice against a melanoma cell line, and independent clones were tested by ELISA for binding to the melanoma cells before and after each panning cycle (Table 3). Less than 1% of the phage in the original libraries bound to the melanoma cells, but after two panning cycles almost 100% of the phage showed strong binding, demonstrating the effectiveness of the panning procedure for achieving rapid enrichment of melanoma-binding fusion phage from both the VH and scFv libraries. The libraries were then absorbed against primary cultures of human fibroblasts to remove phage that react with a normal cell type as well as with the melanoma cells. After the panning and absorption steps, a sample of 488 individual clones from the VH library and 455 clones from the scFv library were tested by ELISA for binding to primary cultures of normal fibroblast and endothelial cells (Table 4). There were 93 clones from the VH library and 11 clones from the scFv library that failed to bind to both the fibroblast and endothelial cells, and these clones were tested for different VH or scFv cDNA inserts by restriction mapping with four enzymes that cut at four base target sites. The VH clones produced 36 different restriction patterns and the scFv clones 5 different restriction patterns, which correspond to the minimum number of different cDNA inserts in the clones because the restriction mapping probably does not detect all sequence differences in the cDNAs. One representative clone for each restriction pattern was further tested by ELISA for binding to a panel of cells consisting of 7 metastatic melanoma lines derived from different patients, primary cultures of melanocytes, and 7 different types of metastatic carcinomas (Table 2). The purpose of the ELISA tests was to identify clones that showed strong binding to the melanoma lines but weak or undetectable binding to the other tumor lines and also to normal melanocyte, fibroblast, and endothelial cells. These VH and scFv clones were then used as probes for immunohistochemistry with the same panel of melanoma lines, normal cell types, and carcinoma lines used for the ELISA tests. The immunohistochemical tests showed that 5 of the clones from the VH library and 2 of the clones from the scFv library stained all of the melanoma cells and none of the other cells (Fig. 2). These 7 clones were also tested for immunohistochemical staining of frozen sections of metastatic melanomas from 7 patients, 3 different types of metastatic carcinomas, a benign nevus, and 15 different normal tissues (Table 2). All 7 clones stained specifically the melanoma cells but not the connective tissue or blood vessels in the melanoma sections, and also did not stain any of the cells in the sections of the carcinomas, nevus, or normal tissues (Fig. 2). On the basis of the immunohistochemical test results, these 7 clones were classified as melanoma-specific. The higher yield of VH than scFv clones suggests that a VH library could be the richer source of tumor-specific clones.

Table 1.

Procedure for isolating and characterizing melanoma-specific clones from VH and scFv fusion phage libraries

| Step | Procedure |

|---|---|

| 1 | Construct fusion phage libraries of VH and scFv molecules derived from the PBL of a vaccinated melanoma patient showing a humoral response to melanoma cells |

| 2 | Pan the libraries against a melanoma cell line |

| 3 | Absorb the libraries against primary cultures of fibroblast cells |

| 4 | Prepare clones of the fusion phage after the panning and absorption steps |

| 5 | Test the clones by ELISA for binding to melanoma cell lines and to primary cultures of normal fibroblast and endothelial cells; save the clones that bind to the melanoma cells but not to the normal cells |

| 6 | Analyze restriction digests of the scFv and VH cDNAs in the selected clones, and classify the clones by their restriction patterns |

| 7 | Test one representative clone for each restriction pattern by ELISA for binding to a panel of different melanoma cell lines, primary cultures of melanocytes, and different types of carcinoma cell lines; the clones that bind to all melanoma lines but do not bind to melanocytes or to the carcinoma lines are saved for immunohistochemical tests |

| 8 | Test the clones by immunohistochemistry for binding to the melanoma and carcinoma cell lines and to primary cultures of fibroblast, endothelial, and melanocyte cells; also test the clones by immunohistochemistry for binding to frozen sections of several metastatic melanomas and carcinomas and a large panel of normal tissues including skin; the clones that bind to the melanoma cells, but do not bind to the carcinoma cells or the normal cells, are designated melanoma-specific clones |

| 9 | Sequence the scFv and VH cDNAs in the melanoma-specific clones |

Table 2.

Cultured cells and frozen sections used for immunohistochemical tests with VH and scFv fusion phage clones

| Cultured cells

|

Sections

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor | Normal | Tumor | Normal |

| Melanoma | Melanocyte | Melanoma | Lung |

| Breast | Endothelial | Lung | Skin |

| Ovarian | Fibroblast | Breast | Breast |

| Prostate | Ovarian | Ovary | |

| Renal | Prostate | Prostate | |

| Pancreatic | Liver | ||

| Gastric | Colon | ||

| Colorectal | Kidney | ||

| Muscle | |||

| Pancreas | |||

| Lymph node | |||

| Brain | |||

| Thyroid | |||

| Endometrium | |||

| Testis | |||

The tumor cell lines were as follows: melanoma, DM341, DM343, DM414, LXSN, A2048, ZAZ6, DCM1; breast, SK-BR3; ovarian, SK-OV3; prostate, DU145; renal, Caki-1; pancreatic, Colo347; gastric, MS; colorectal, HT29. Melanocytes and fibroblasts were prepared from human foreskins and maintained for three to six passages, and endothelial cells were prepared from human umbilical cords and maintained for three to six passages. The frozen sections were prepared from tissue specimens stored in the Yale University Critical Technologies facility.

Table 3.

Enrichment for melanoma-binding clones after panning the VH and scFv libraries against melanoma cells

| Panning cycle | Library | Number of clones

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Tested | Binding | ||

| 0 | VH | 95 | 0 |

| scFv | 95 | 0 | |

| 1 | VH | 48 | 11 |

| scFv | 96 | 1 | |

| 2 | VH | 48 | 47 |

| scFv | 48 | 48 | |

The phage clones were prepared by infecting E. coli K 91 KanR cells with a low phage-to-cell ratio and plating for colonies on 2× YT tet agar. The phage for cycle 0 were from the original fusion phage libraries, and the phage for cycles 1 and 2 were from the elution steps after each panning cycle. The colonies were inoculated into 2× YT tet broth and grown 24 hr at 37°C, and the cells were then removed by centrifugation. The phage in the supernate were tested by ELISA for binding to melanoma cells A2058; an absorbance >0.1 was scored as binding.

Table 4.

Characterization of the melanoma-binding VH and scFv fusion phage clones

| Fusion phage library | Clones tested | Melanoma-specific clones (preliminary)* | Restriction groups† | Melanoma-specific clones (final)‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VH | 488 | 93 | 36 | 5 |

| scFv | 455 | 11 | 5 | 2 |

The preliminary classification as melanoma-specific was based on the binding of phage in ELISA tests to autologous melanoma 414 cells but not to normal fibroblast and endothelial cells.

Restriction mapping was done as described in Materials and Methods, and clones showing identical restriction patterns were classified in the same restriction group.

The final classification as melanoma-specific was based on the overall results of ELISA and immunohistochemical tests (Table 2). The melanoma-specific clones showed binding to all melanoma cell lines and sections, but not to the primary cultures of normal cells or the carcinoma cell lines, or the sections of normal tissues or carcinomas.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemical tests for binding of VH fusion phage C55 and control phage fUSE5 to cultured cells (A–H) and frozen tissue sections (I–P) as follows. The detection procedure for all panels involved a peroxidase-labeled antiphage second antibody (Pharmacia) followed by the substrate VIP (Vector Laboratories). The slides were counterstained with methyl green and photographed in both brightfield and darkfield. (A) C55/melanoma/bright. (B) C55/melanoma/dark. (C) fUSE5/melanoma/bright. (D) fUSE5/melanoma/dark. (E) C55/melanoma/bright. (F) C55/melanoma/dark. (G) C55/prostate carcinoma/bright. (H) C55/melanocyte/dark. (I) C55/melanoma/bright. (J) C55/melanoma/dark. (K) fUSE5/melanoma/bright. (L) fUSE5/melanoma/dark. (M) C55/normal skin/bright. (N) C55/normal skin/dark. (O) C55/prostate carcinoma/bright. (P) C55/prostate carcinoma/dark. The VIP substrate produces a purple color in brightfield (see A and I) and a golden color in darkfield (see B and J). In I and J the melanoma tissue is marked as m and the connective tissue is marked as c. The melanoma cell line was A2080 and the prostate cell line was DU-145. All of the fusion phage clones shown in Fig. 3 were tested immunohistochemically for binding to the entire panel of cells and sections listed in Table 2. The results showed strong binding to the melanoma cell lines and sections, similar to A, B, I, and J, and no detectable binding to any of the other cells or sections, similar to E, F, G, H, M, N, O, and P.

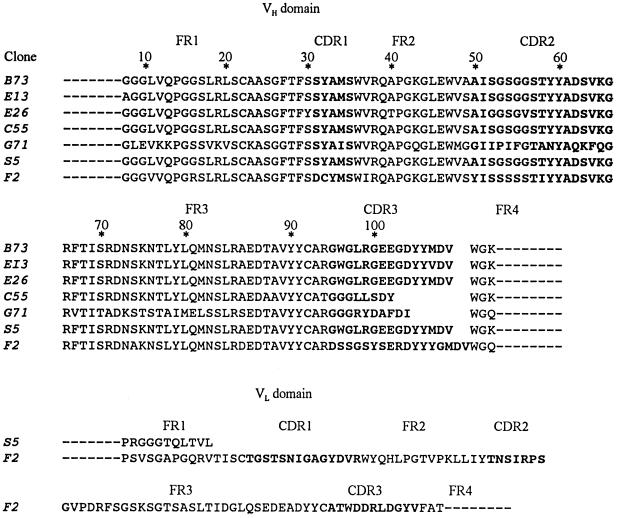

The amino acid sequences of the VH and VL domains encoded by the cDNA inserts in the melanoma-specific clones are shown in Fig. 3. Clone S5 from the scFv library is identical to V86, which was previously isolated from the same library (2); this clone has a truncated VL domain resulting from the cleavage of an extraneous SfiI cloning site in the VL cDNA during construction of the library (2). The binding specificity of V86 depends solely on the VH domain (2), which should also be represented in the VH library; therefore, it should be possible to isolate this VH domain as a melanoma-specific clone from the VH library. B73 is such a clone, and two other clones from the VH library, namely E13 and E26, are closely related to B73; the differences from B73 occur at positions 49 and 100G in E13 and at positions 30, 40, 49, 52, and 55 in E26. Clones C55 and G71 from the VH library have major differences from the other VH clones in both the length and sequence of the CDR3 region. Clone F2 from the scFv library encodes a full-length scFv molecule which shows major sequence differences from all of the VH clones in the CDR1, CDR2, and CDR3 regions of the VH domain. Therefore at least four of the clones in Fig. 3 probably bind to different epitopes. A more extensive screen of the two libraries could yield additional melanoma-specific clones with different VH domains.

Figure 3.

Amino acid sequences encoded by cDNA inserts in melanoma-specific clones from VH and scFv fusion phage libraries. Clones B73, E13, C55, and G71 were isolated from the VH fusion phage library, and clones S5 and F2 were from the scFv fusion phage library. The amino acid sequences were deduced from the complete nucleotide sequences of the cDNA inserts in the clones; the 15-residue linker between the VH and VL domains of clones S5 and F2 is not shown. The complementarity determining regions (CDRs) are demarcated by boldface type from the framework regions (FRs). The dashed lines at the amino end of the FR1 region and at the carboxyl end of the FR4 regions indicate residues derived from the primers used in the PCR synthesis, The reference positions of the residues are indicated by an asterisk, according to the system of Kabat et al. (4); multiple residues occur at positions 52 (52a) and 82 (82a–c); positions after 100 are designated 100A–K.

The V, D, and J germ-line genes that show the closest nucleotide match to the VH domains of the clones in Fig. 3 were identified by scanning the IMGT databases (5). The codon differences between the VH domains of the clones and their closest germ-line genes (Table 5) provide clues about the origins and relationships of the clones, as follows. (i) B73, E13, and E26 are closest to the same V, D, and J germ-line genes and show the same nucleotide changes from the germ-line genes in 3 of the FR3 codons and in 11 of the CDR3 codons, which is compelling evidence that the three clones derive from the same founder clone. The codon differences from the germ-line V gene, and some of the codon differences from the germ-line D and J genes, probably resulted from antigen-selected somatic mutants generated in the vaccinated patient. E26 shows the highest level of codon changes including two expressed changes in the CDR2 region, suggesting that E26 has sustained the most extensive mutations in response to the melanoma vaccine and therefore could have the highest affinity for melanoma cells. (ii) C55 is closest to the same V gene as B73, E13, and E26, but the closest D and J genes are different. G71 and F2 are closest to other V, D, and J genes. Thus, the six melanoma-specific clones appear to derive from three V genes, three D genes, and four J genes.

Table 5.

Codon differences between VH domains of fusion phage clones and closest germ-lines genes

| Clone | Closest germline V gene | VH Family | Positions where codons differ

|

Closest germ-line D/J genes | Positions where codons differ

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silent | Expressed | Silent | Expressed | ||||

| B73 | DP-47 | VH3 | 88, 89 | 49, 94 | D21-10/JH6C | 99 | 95, 96, 97, 98, 100, 100A, C, D, E, H, I, J |

| E13 | DP-47 | VH3 | 8, 73, 88, 89 | 94 | D21-10/JH6C | 99 | 95, 96, 97, 98, 100, 100A, C, D, E, H, I, J, K |

| E26 | DP-47 | VH3 | 42, 80, 81, 88, 89 | 30, 40, 52, 55, 94 | D21-10/JH6C | 99 | 95, 96, 97, 98, 100, 100A, C, D, E, H, I, J |

| C55 | DP-47 | VH3 | 89 | 87, 94 | D4-b/JH4b | 99 | 97, 98, 100, 100A, C |

| G71 | DP-88 | VH1 | 9 | DA5-a/JH3b | 97 | 98, 100, 100A, B | |

| F2 | DP-35 | VH3 | 15, 71, 73, 88 | 11, 13, 16, 32, 54, 84 | DA5-a/JH6b | 95 | 96, 97, 98, 99, 100B, C, D |

Because a VH domain alone can bind specifically to melanoma cells, as indicatd by the 5 VH clones, the VH domain of the scFv clone F2 was separately expressed on a fusion phage and tested by ELISA for binding to melanoma cells. No binding was detected (data not shown), indicating that the antibody repertoire of patient DM414 contains VH domains that require a VL partner for binding to melanoma cells as well as VH domains that can bind without a VL partner.

The VH domains in the VH library presumably are associated with VL domains in the antibody repertoire of patient DM414. To study the effect of linking VL domains to the VH domains of the melanoma-specific clones isolated from the VH library, four new scFv libraries were constructed, each library encoding the VH domain of E13, E26, C55, or G71 randomly linked to VL domains from the DM414 repertoire; individual clones from the scFv libraries were tested by ELISA for binding to melanoma cells. Although most VL domains inhibited the binding to melanoma cells, it was possible to isolate scFv clones comparable in specificity and affinity to the corresponding VH clones by panning the V86, E13, E26, C55, and G71 scFv libraries against melanoma cells (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The combining site of an antibody generally consists of a tightly associated pair of heavy and light chain variable domains (VH and VL), each domain contributing to the specificity and affinity of the antibody. A remarkable exception was described recently for the antibody repertoire of the camel, which contains IgG molecules consisting mostly of two heavy chains but no light chains (6), each VH domain forming a separate combining site (7). These heavy chain camel antibodies react with a broad spectrum of antigens, indicating that the immune system of the camel can generate a diverse repertoire of functional antibodies devoid of light chains. Earlier studies with isolated heavy and light chains of several mouse monoclonal antibodies indicated that the binding specificity can reside primarily in the heavy chain, the light chain contributing mainly to the affinity (8, 9). With the introduction of PCR technology for synthesizing cDNAs encoding the variable domains of antibodies (10, 11), the specificity and affinity of VH and VL domains could be analyzed either separately or coupled in a Fab or scFv molecule. Several such studies have further demonstrated a dominant role of VH domains in determining antibody specificity (12, 13), and in some cases the affinity of the VH domain alone was comparable to the affinity of the complete antibody. The recent solution of the x-ray structure for the VH domain from a camel heavy chain anti-lysozyme antibody complexed with lysozyme provides a detailed picture of the molecular basis for VH recognition of a specific epitope (7).

The first evidence that human VH domains could bind specifically without a VL partner was obtained in the course of screening a human scFv fusion phage library derived from the PBL of a vaccinated melanoma patient (Abdel-Wahab et al., personal communication) for melanoma-specific clones: One of the isolated clones, called V86, contained a complete VH domain but was missing most of the VL domain (2). This unexpected finding suggested that the antibody repertoire of the melanoma patient might contain additional VH domains that bind specifically to melanoma cells without requiring an associated VL domain. However, the occurrence of other clones similar to V86 in the scFv library depends on the presence of an extraneous SfiI restriction cloning site near the 5′ end of the VL cDNA (2), which is an extremely rare event. To screen for such VH domains we constructed a VH fusion phage library derived from PBL of the same melanoma patient, and we compared this library as a source of melanoma-specific clones with the original scFv library that contained the same repertoire of VH domains as the scFv library. The VH domains are displayed without a VL domain in the VH library or randomly paired with VL domains in the scFv library. Because only a fraction of all possible random pairings of VH and VL domains can be represented in a scFv library of average size (about 108 founder clones), there is virtually no chance of a VH domain reassociating with its original VL partner from the patient’s B cell. Therefore, the comparison of the two libraries is based on the binding specificity of VH domains displayed alone in the VH library or randomly paired with new VL partners in the scFv library. A limited screen of the two libraries for melanoma-specific clones yielded five different VH clones and one scFv clone. The binding to melanoma cells usually was inhibited when the VH domains in the VH clones were randomly linked to VL domains to form scFv molecules; therefore, these clones might not have been isolated from an average size scFv library. In contrast to the five VH clones, the VH domain in the scFv clone does not bind to melanoma cells when displayed without a VL partner; consequently, this VH domain could not have been isolated from the VH library. It appears that the most effective strategy for isolating different tumor-specific clones from fusion phage libraries involves panning both VH libraries and scFv or Fab combinatorial libraries against tumor cells, to include both the VH domains that do not require and those that do require a VL partner for binding to the tumor cells.

The vaccinated melanoma patient DM414 whose lymphocytes were used for this study showed a significantly stronger humoral response against the tumor after completion of the vaccination protocol (Abdel-Wahab et al., personal communication), suggesting that the patient’s B cells had undergone affinity maturation and selection driven by antigens expressed on the melanoma cells used for the vaccination. The finding that most of the clones isolated from the DM414 libraries have major sequence differences from the closest V, D and J germ-line genes provides further evidence that tumor-specific antibodies were generated in response to the vaccination protocol. Similar vaccination trials are in progress for various cancers, including breast, prostate, ovarian, glioma, neuroblastoma, colon, lung, and renal in addition to melanoma (14). The protocols involve injections of autologous or allogeneic tumor cells or cell lysates, either alone or together with autologous dendritic or fibroblast cells; to enhance an immune response the cells are usually transfected in vitro with a cytokine gene or the cytokine is added separately. The B cells of cancer patients participating in these trials comprise a key source of antibody mRNAs for constructing the VH and scFv fusion phage libraries needed to search for tumor-specific clones. Having a library derived from B cells that respond to a tumor, rather than a “naive” library derived from B cells of normal individuals (15), should improve the chance of finding rare tumor-specific clones.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the assistance of Dr. Ying Sun in panning the libraries and Dr. Linda Guiterrez in providing frozen tissue sections and examining stained sections. Support for this project came from a Special Use Fund administered by Dr. William H. Konigsberg, the Joseph H. Konigsberg Melanoma Memorial Fund, and a gift from the Pasteur-Merieux-Connaught Company.

ABBREVIATIONS

- scFv

single-chain Fv molecule

- VH and VL

variable domain of a heavy chain and light chain, respectively

- CDR1

2 and 3, complementarity-determining regions of the variable domains

- PBL

peripheral blood lymphocytes

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

Footnotes

References

- 1.Cai X, Garen A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6537–6542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai X, Garen A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6280–6285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith P G, Scott J K. Methods Enzymol. 1993;217:228–257. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)17065-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kabat E A, Wu T T, Reid-Miller M, Perry H M, Gottesman K S. Sequences of Proteins of Immunological Interest. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giudicelli V, Chaume D, Bodmer J, Müller W, Busin C, Marsh S, Bontrop R, Marc L, Malik A, Lefranc M-P. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:206–211. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammers-Casterman C, Atarhouch T, Muyldermans S, Robinson G, Hamers C, Songa E B, Bendahman N, Hamers R. Nature (London) 1993;363:446–448. doi: 10.1038/363446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desmyter A, Transue T R, Ghahroudi M A, Thi, Min-Hoa D, Poortmans F, Hamers R, Muyldermans S, Wyns L. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:803–811. doi: 10.1038/nsb0996-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haber E, Richards F F. Proc R Soc London Ser B. 1963;166:176–187. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1966.0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaton J C, Klinman N R, Givol D, Sela M. Biochemistry. 1968;7:4185–4195. doi: 10.1021/bi00852a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marks J, Hoogenboom H, Bonnert T, McCafferty J, Griffiths A, Winter G. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:581–597. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90498-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbas C F, III, Kang A S, Lerner R A, Benkovic S J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7978–7982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.18.7978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward E S, Güssow D, Griffiths A D, Jones P T, Winter G. Nature (London) 1989;341:544–546. doi: 10.1038/341544a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jang Y-Y, Lecerf J-M, Stollar B D. Mol Immunol. 1996;33:197–210. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(95)00094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roth J A, Cristiano R J. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:21–39. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaughan T J, Williams A J, Pritchard K, Osbourn J K, Pope A R, Earnshaw J C, McCafferty J, Hodits R A, Wilton J, Johnson K S. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:309–314. doi: 10.1038/nbt0396-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]