Abstract

Flavonoids are secondary metabolites derived from phenylalanine and acetate metabolism that perform a variety of essential functions in higher plants. Studies over the past 30 years have supported a model in which flavonoid metabolism is catalyzed by an enzyme complex localized to the endoplasmic reticulum [Hrazdina, G. & Wagner, G. J. (1985) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 237, 88–100]. To test this model further we assayed for direct interactions between several key flavonoid biosynthetic enzymes in developing Arabidopsis seedlings. Two-hybrid assays indicated that chalcone synthase, chalcone isomerase (CHI), and dihydroflavonol 4-reductase interact in an orientation-dependent manner. Affinity chromatography and immunoprecipitation assays further demonstrated interactions between chalcone synthase, CHI, and flavonol 3-hydroxylase in lysates from Arabidopsis seedlings. These results support the hypothesis that the flavonoid enzymes assemble as a macromolecular complex with contacts between multiple proteins. Evidence was also found for posttranslational modification of CHI. The importance of understanding the subcellular organization of elaborate enzyme systems is discussed in the context of metabolic engineering.

The organization of enzymes into macromolecular complexes localized to specific subcellular sites is emerging as a central feature of cellular metabolism. The now-classic experiments of Zalokar (1) and Kempner and Miller (2) first indicated that the cytosol contains little if any soluble or freely diffusing protein. Extensive work with the enzymes of the Krebs TCA cycle, glycolysis, fatty acid oxidation, and other metabolic pathways has since pointed to subcellular organization as critical for many aspects of enzyme function, including maintaining high local substrate concentrations, separating anabolic and catabolic events, maintaining stereospecificity, and sequestering highly reactive or toxic intermediates (reviewed in refs. 3 and 4). An underlying assumption of many of these studies has been that interactions among enzymes, membranes, and the cytoskeleton create the foundation for this organization. Experimental evidence for these interactions has begun to emerge in a number of systems (5, 6) and is being supported by structural information identifying channels between active sites on the same or different polypeptides (7–9). Thus, there is strong support for the long-standing hypothesis that enzymes have both structural and catalytic functions, with concomitant constraints on the evolution of protein structure (10–12).

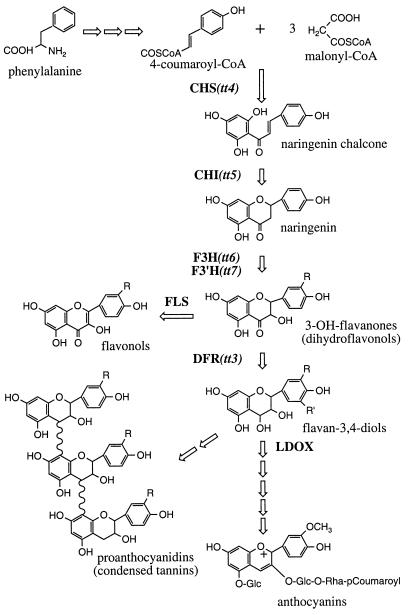

The flavonoid pathway of higher plants provides a powerful biochemical genetic system for studying metabolic organization. Flavonoids are secondary metabolites derived from phenylalanine and acetyl CoA (Fig. 1) that perform a variety of important functions in plant growth, reproduction, and survival and also serve as important micronutrients in human and animal diets (reviewed in refs. 13–16). Biosynthesis occurs in the cytosol, resulting in the production of an enormous variety of products that are then transported into the vacuole via, in at least some species, an ATP-dependent glutathione pump. Because these compounds are not essential under laboratory conditions, flavonoid mutants have been identified in numerous plant species based on altered seed or flower pigmentation. Genes encoding flavonoid structural and regulatory proteins have been cloned and characterized in a variety of plants and found to be expressed in response to a wide range of external and internal cues. In Arabidopsis, genes have been isolated for seven different flavonoid enzymes: chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H), flavonol synthase, dihydroflavonol reductase (DFR), and leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase (Fig. 1) (refs. 17–21; C. Cobbett, personal communication; A. Bandara and B.W.-S., unpublished results). All but one of these enzymes, flavonol synthase, are encoded by single-copy genes, allowing null alleles that disrupt flavonoid biosynthesis throughout the plant to be identified for CHS, CHI, F3H, F3′H, and DFR. The sequential expression of flavonoid mRNAs and proteins during development and in response to light (17, 18, 22–24) suggests that controlled synthesis of flavonoid enzymes could mediate the production of specific end products, possibly via the assembly of spatially and temporally distinct enzyme complexes.

Figure 1.

Schematic of flavonoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. CHS catalyses the first committed step in this pathway. Three general classes of end product are produced in Arabidopsis: flavonols, anthocyanins, and proanthocyanidins (or condensed tannins). Enzymes are indicated in bold, with the corresponding genetic loci in parentheses. FLS, flavonol synthase; LDOX, leucoanthocyanidin dioxygenase.

The concept that the flavonoid, sinapate, and lignin pathways could be organized as enzyme complexes was first proposed by Stafford (25), in part, to explain how these pathways are able to compete for common intermediates (reviewed in ref. 26). Soon thereafter, Fritsch and Grisebach (27) suggested that flavonoid biosynthesis takes place partly or completely on membranes, based on analysis of enzyme activities in permeabilized cells and microsomes (reviewed in ref. 28). Hrazdina and Wagner (29, 30) subsequently performed channeling, gel filtration, and cell fractionation studies that indicated that phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, cinnamate-4-hydroxylase, CHS, and UDP-glucose flavonoid glucosyltransferase function as part of one or more membrane-associated enzyme complexes in amaryllis, buckwheat, and red cabbage. Further immunocytochemical studies indicated that CHS was located at the cytoplasmic face of the rough endoplasmic reticulum (31). This led to a model in which the phenylpropanoid and flavonoid pathways are organized as a linear array of enzymes loosely associated with the endoplasmic reticulum and anchored via the cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenases, cinnamate-4-hydroxylase and F3′H (32, 33). However, the apparent fragility of the enzyme interactions and the inability to isolate an intact complex from lysed plant cells slowed efforts to further characterize this organization and to define its role in regulating phenylpropanoid and flavonoid biosynthesis. The availability of cloned genes for the enzymes of the core flavonoid pathway, convenient protein expression systems, and sensitive approaches for detecting protein–protein interactions now offers opportunities for exploring these questions further. Here we describe the use of biochemical genetic methods to provide evidence for specific protein–protein interactions among four enzymes of flavonoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis.

Materials and Methods

Two-Hybrid Assays.

Full-length cDNAs encoding Arabidopsis CHS, CHI, and DFR were amplified by PCR from existing clones in pBluescript KS(+) (34). The sequence of the upstream primer was 5′-ATACTCGAGGCTGCAGGAATTCATG-3′ for CHS and CHI and 5′-ATGTCGACGCTGCAGGAATTCATG-3′ for DFR, and the downstream primer for all three clones was 5′-ATAGCGGCCGCCCCTCGTGGACGAC-3′. The products were digested with NotI and either XhoI (CHS and CHI) or SalI (DFR) and then subcloned into the two-hybrid vectors, pBI-880 (containing the Gal41–147 DNA-binding domain) and pBI-881 (containing the Gal4768–881 transactivation domain) (ref. 35; generously provided by W. L. Crosby, National Research Council, Plant Biotechnology Institute, Canada). Correct orientation and in-frame fusion of the cDNAs were confirmed by sequencing as described previously (20). The yeast strain HF7c (36) was transformed with pairwise combinations of the fusion constructs by using the method of Gietz and Schiestl (37). Double transformants were selected on leu-, trp- minimal medium (38). Interactions between fusions were assayed after 4 days of incubation on leu-, trp-, his- minimal medium containing 5 mM 3-aminotriazole (Sigma). To quantify β-galactosidase activity, overnight cultures were grown under appropriate selection conditions. Cell density was determined by direct counting by using a hemocytometer, and 109 yeast cells were collected by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 10 min. Cells were washed and spheroplasts were prepared by using β-1,3-glucanase from Arthrobacter luteus (ICN) as described in Ausubel et al. (38). β-Galactosidase was measured by using the Galacto-Light chemiluminescent reporter assay (Tropix, Bedford, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol; luminescence was measured with a Lumat LB 9501 luminometer (Berthold, Nashua, NH).

Recombinant Protein Expression and Purification.

Construction of CHS and CHI as fusions to the carboxyl terminus of thioredoxin (TRX) in pET32a was described previously (19). Expression in E. coli strain BL21(DE3) (Novagen) was induced by incubation with 1 mM dioxane-free isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (United States Biochemical) at 25°C for 4 h. Cells were collected at 7,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, washed with 0.25 vol of ice-cold wash buffer (25 mM Hepes, pH 8.0/1 mM EDTA), and then frozen at −80°C. The cell pellets were resuspended in 3.5 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 8.0/150 mM NaCl/2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/1 mM PMSF) per gram of cells and then sonicated (3 × 10 sec) on ice. DNase I (Boehringer Mannheim) and Tween-20 were added to final concentrations of 40 μg/ml and 1%, respectively. Lysates were agitated gently for 20 min at 25°C. After centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 10 min, recombinant protein was purified from the supernatants by using TALON metal affinity resin (CLONTECH) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The columns were washed with 10 vol of lysis buffer and then with 10 vol of 5 mM Hepes, pH 8.0/500 mM NaCl/1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/1% Tween-20, and, finally, with 10 vol of 5 mM Hepes, pH 8/150 mM NaCl/1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/1% Tween-20. Elution was in 50 mM Pipes, pH 6.5/150 mM NaCl/50 mM imidizole/1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/1% Tween-20. Successful expression and purification were verified by SDS/PAGE. Purified recombinant protein was dialyzed against 50 mM Mops, pH 7.2/150 mM NaCl/1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/0.1% Tween-20 at 4°C by using Slide-A-Lyzer dialysis cassettes (10,000 molecular weight cutoff; Pierce).

Plant Material.

Arabidopsis seedlings were grown on MS-agar medium containing 2% sucrose (22) in constant white light (100 μE/m2) at 22°C for 3 days. Seedlings were washed with distilled water, gently blotted dry on Whatman No. 1 paper, and then used fresh or stored frozen at −80°C. The Columbia ecotype was used, except in the affinity chromatography experiments, where Landsberg wild type, tt4(2YY6), and tt5(86) were also included.

Affinity Chromatography.

Purified recombinant TRX-CHS or TRX-CHI was covalently attached to Affi-Gel 10 activated resin (Bio-Rad) in 100 mM Mops, pH 7.2/150 mM NaCl/1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/0.1% Tween-20/80 mM CaCl2 for 4 h at 4°C. The coupling reaction was quenched by adding ethanolamine to 100 mM for 1 h. Unbound protein was removed by washing with 10 vol of 20 mM Tris, pH 7.2/150 mM NaCl/1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/0.1% Tween-20 three times. Coupling efficiency was assessed based on the amount of protein present in solution before and after binding as determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay. Greater than 90% of the protein was routinely bound to give a concentration of approximately 35 mg protein per ml of resin.

To prepare the extracts for affinity purification of flavonoid enzymes, seedlings were ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen, suspended in plant lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.2/150 mM NaCl/1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol/70 μg/ml DNase I/0.6% Nonidet P-40/0.6% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate [CHAPS]/4 mM pefabloc/1 μM aprotinin/1 μM PMSF/4 μM benzamidine/2 μM leupeptin/2 μM pepstatin), and incubated at 25°C for 20 min. Insoluble material was pelleted at 30,000 × g for 10 min at 20°C, and 400 μl of the remaining soluble plant lysate was incubated with 25 nmol of resin-coupled ligand with gentle agitation at 4°C for 2 h. The resin was pelleted at 500 × g for 30 sec and resuspended in 30 vol of plant lysis buffer without DNase. Bound proteins were eluted in 30 μl of 65 mM Tris, pH 6.8/2% SDS/15% glycerol at 65°C for 5 min, and the resin was pelleted at 500 × g for 30 sec. One-fifth of the eluted sample was used for immunoblot analysis (see below).

Immunoprecipitation Assay.

For affinity purification of polyclonal anti-CHI IgY (39), 100 mg of crude antibody preparation was passed over 80 mg of TRX-CHI fusion protein coupled to 2 ml of Affi-Gel 10 (described above) three times at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. The column was washed with 20 vol of 10 mM Tris, pH 7.2/0.3 M NaCl/0.05% Tween-20. Bound antibodies were eluted by using 10 vol of 0.1 M glycine, pH 2.5, at a flow rate of 2 ml/min and then neutralized with 1/10 vol of 1 M Tris, pH 7.2. Efficient elution was verified by monitoring heavy and light chain peptides using reducing SDS/PAGE. Immunoreactivity of the antibody was tested in immunoblot analysis. A total of 0.9 mg of polyclonal anti-CHI was recovered.

Antibodies were covalently linked to Affi-Gel Hz (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, with 850 μg of affinity-purified anti-CHI IgY or 8.5 mg of protein from preimmune serum coupled to 1 ml of resin. Soluble plant lysate (400 μl), prepared from seedlings as above but without 2-mercaptoethanol, was mixed with 10 μg of immobilized anti-CHI IgY and agitated for 2 h at 4°C. Resin was collected by centrifugation at 500 × g for 30 sec and then washed with 30 bed volumes of plant lysis buffer without DNase. Proteins were eluted from the resin in 50 μl of 65 mM Tris, pH 6.8/2% SDS/15% glycerol at 65°C for 5 min, and the resin was pelleted by centrifugation as before. One-fifth of the elution volume was used for immunoblot analysis.

Analysis of CHI Molecular Mass.

Seedlings were ground in liquid nitrogen and suspended in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris, pH 7.2/150 mM NaCl/70 g/ml DNase I/0.6% Nonidet P-40/0.6% CHAPS. The samples then were incubated with 5 mM benzamidine/1 mM PMSF/2 μm leupeptin/2 μm pepstatin/1 μm aprotinin/4 mM pefabloc and either 2 mM manganese, 2 mM magnesium, 5 mM EDTA, 1 M hydroxylamine, 1 M Tris (pH 7.2), or 0.2 M KOH, at 25°C with gentle agitation. Samples were collected at various time points, mixed with an equal volume of 125 mM Tris, pH 6.8/4% SDS/20% glycerol, heated at 65°C for 5 min, and then frozen at −80°C before immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblot Analysis.

Protein samples were fractionated by reducing SDS/PAGE and electroblotted to 0.2 μM supported nitrocellulose (Bio-Rad). Filters were incubated with anti-CHI (39) or anti-CHS (19) IgY antibodies, diluted in 1× PBS-T as follows: anti-CHS (1:1,000), anti-CHI (1:200), affinity-purified anti-CHI (1:5,000), and anti-F3H (1:500). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated donkey whole IgG anti-IgY (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used as the secondary antibody at a 1:125,000 dilution. Antiphosphoserine, antiphosphotyrosine, antiphosphotryptophan, and antiphosphoprotein antibodies (Zymed) were used at dilutions of 1:10,000, and a HRP-conjugated anti-IgG was used as the secondary antibody at a 1:50,000 dilution. HRP activity was detected by using Supersignal Ultra (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and BioMax film (Kodak).

Results

Arabidopsis Flavonoid Enzymes Interact with One Another in Defined Orientations.

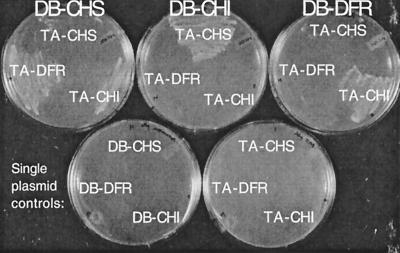

As an initial test of the hypothesis that flavonoids are synthesized by a complex of soluble enzymes, the two-hybrid system was used to assay protein–protein interactions between several key Arabidopsis flavonoid enzymes. CHS, CHI, and DFR each were fused to the C terminus of the Gal41–147 DNA-binding and Gal4768–881 transactivating domains (40). The constructs were introduced into the yeast host, HF7c, both individually and in all nine possible pairwise combinations. Activation of the His3 reporter by interactions between fusion proteins was assayed by screening for histidine prototrophy and 3-aminotriazole resistance. This assay revealed that CHS, CHI, and DFR interact with DFR, CHS, and CHI, respectively (Fig. 2). However, these interactions were detected only for specific fusion pairs, suggesting that the orientation of the flavonoid enzymes in this system was essential for these interactions.

Figure 2.

Two-hybrid assay for protein–protein interactions among Arabidopsis flavonoid enzymes. Growth of transformed HF7C yeast cells was assayed on his-, 5 mM 3-aminotriazole medium at 30°C for 4 days. The top row illustrates a representative interaction assay. The Gal41–147 DNA-binding domain (DB) fusion is indicated at the top of each plate, and the Gal4768–881 transactivation domain (TA) fusion is indicated in each sector. The bottom row shows the controls—yeast cells transformed with single plasmids carrying TA fusions, as indicated.

To quantify these results, β-galactosidase activity was assayed in the soluble protein fraction of yeast spheroplast lysates. Yeast cells expressing interacting flavonoid enzymes based on a his+ phenotype exhibited approximately half the β-galactosidase activity of cells expressing an SV40 T antigen/p53 interacting pair (data not shown). Moreover, this was approximately 20 times the level of activity observed in control yeast cells containing any of these plasmids alone (data not shown). Because the His3 and β-galactosidase reporter genes in HF7c share only the cis elements for Gal4 binding (36), these results indicate that histidine prototrophy is the result of specific protein–protein interactions between flavonoid enzymes.

Flavonoid Enzymes Can Be Purified from Plant Lysates by Affinity Chromatography.

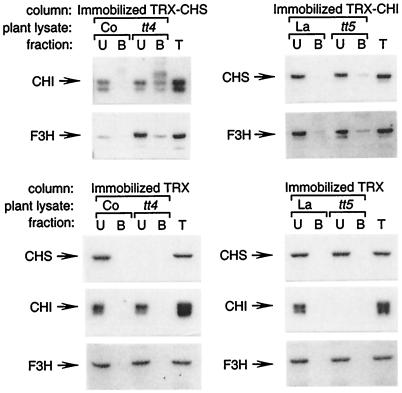

To extend the results of the two-hybrid experiments, protein–protein interactions between flavonoid enzymes were assayed in Arabidopsis seedling lysates by affinity chromatography. Recombinant TRX-CHS or TRX-CHI was covalently attached to Affi-Gel 10 resin. Unlike previous efforts to use GST fusion proteins bound to glutathione-beaded agarose or TRX fusion proteins bound to TALON metal affinity resin (not shown), the covalently bound ligand did not leach appreciably from the resin because recombinant protein was not detected in subsequent immunoblot analysis of affinity-purified plant protein (see below). Crude soluble protein was prepared from Arabidopsis seedlings grown for 3 days under continuous white light in the presence of sucrose, conditions under which flavonoid enzymes accumulate to high levels (19, 39). Proteins that bound to the immobilized TRX-CHI or TRX-CHS were examined by immunoblot analysis by using antibodies against CHS, CHI, or F3H; antibodies against DFR were not available for these experiments. A very small amount of CHS and F3H protein could be eluted reproducibly from the immobilized TRX-CHI by using lysates from wild-type seedlings (Fig. 3). Binding of CHI and F3H to TRX-CHS was also near the limit of detection. However, using lysates from tt4 and tt5 seedlings, which lack CHS and CHI protein, respectively (19), significant amounts of CHS, CHI, and F3H could be eluted from the affinity columns. This suggests that the endogenous enzymes compete for binding with the recombinant protein immobilized on the affinity column. In control experiments, immobilized TRX did not bind detectable amounts of CHS, CHI, or F3H from either wild-type or mutant plant lysates, demonstrating that binding was specific for the recombinant CHS and CHI proteins. These experiments extend the results of the two-hybrid analysis, showing that CHS, CHI, and F3H enzymes produced in plant cells can form specific protein–protein interactions.

Figure 3.

Immunoblot analysis of Arabidopsis flavonoid enzymes recovered by affinity chromatography. Recombinant CHS or CHI was covalently attached to Affi-Gel 10 resin and used as an affinity matrix to bind interacting flavonoid enzymes from wild-type Columbia (Co), Landsberg (La), tt4(2YY6) (CHS null), or tt5 (CHI null) lysates. Bound endogenous plant proteins were eluted from resin and identified by using immunoblot analysis. U, unbound; B, bound proteins from lysate; and T, total lysate control.

Anti-CHI Coimmunoprecipitates CHS and F3H.

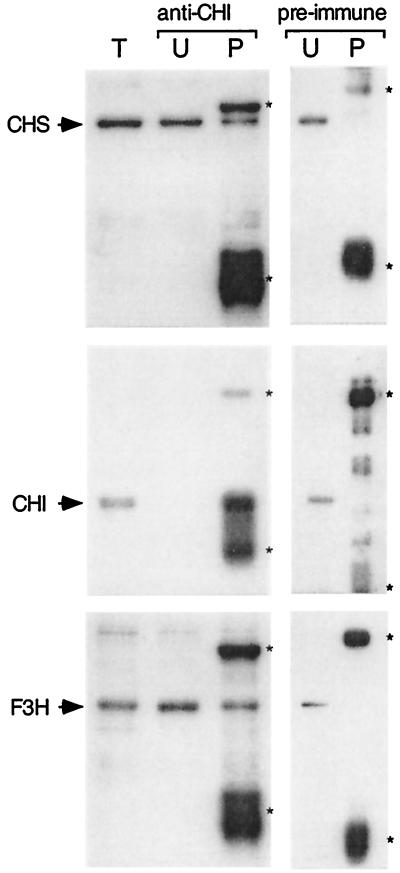

As a third approach to detecting associations among Arabidopsis flavonoid enzymes, affinity-purified anti-CHI IgY was used in immunoprecipitation experiments with lysates from 3-day-old seedlings. Protein A- or protein G-coupled Sepharose did not bind IgY with sufficient affinity for use in these experiments (data not shown). Instead, anti-CHI IgY was coupled directly to Affi-Gel Hz resin via stable hydrazone linkages between the matrix and the heavy chain oligosaccharide residues of the IgY molecules. The resin-linked antibody effectively depleted the crude plant lysate of CHI enzyme (Fig. 4). A portion of the CHS and F3H present in the lysates was also recovered in the precipitated fraction. IgY from preimmune serum did not immunoprecipitate any of these enzymes in control experiments. This provides additional evidence for the association of CHS and F3H with CHI in the plant cell.

Figure 4.

Coimmunoprecipitation of flavonoid enzymes. Affinity-purified anti-CHI bound to Affi-Gel Hz resin was used to precipitate CHI from crude soluble protein extracts of 3-day-old seedlings. A control experiment was performed by using the corresponding preimmune serum. Immunoblot analysis was used to identify other flavonoid enzymes that coimmunoprecipitated with CHI. T, total lysate; U, unbound; and P, precipitated proteins. Asterisks indicate the positions of the light and heavy chains of the IgY (anti-CHI) or IgG (preimmune serum) that were eluted from the resin together with the immunoprecipitated proteins.

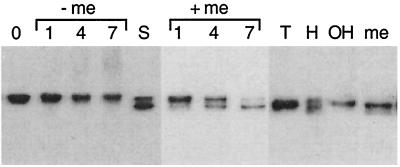

Evidence for Covalent Modification of CHI.

The native Arabidopsis CHI protein has a predicted molecular mass of 26 kDa (20), yet the protein detected by immunoblot analysis of plant extracts consistently migrates at approximately 31 kDa on SDS-polyacrylamide gels (19, 39). During the affinity chromatography experiments, some of the CHI protein in the crude protein extracts was found to change to an apparent mass of approximately 26 kDa after incubation with affinity resin at 4°C for 2 h in buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol (Fig. 3). It subsequently was found that incubation of plant cell lysates in buffer containing 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol at room temperature for 7 h resulted in a gradual shift of almost all of the CHI protein from 31 to 26 kDa (Fig. 5). This change in apparent mass was not observed when the 2-mercaptoethanol was omitted from the buffer. The high-molecular-mass species was not an artifact resulting from incomplete inhibition of disulfide bond formation during extraction, however, because only the 31-kDa form was detected immediately after extraction even in the presence of 2-mercaptoethanol concentrations as high as 5 M (Fig. 5). Moreover, CHI overexpressed in E. coli remained as a single molecular mass species, even in the presence of 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. This indicates that CHI is specifically modified within the plant cell to a higher-molecular-mass form. The presence of 2 mM manganese, 2 mM magnesium, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM benzamidine, 1 mM PMSF, 2 μm leupeptin, 2 μm pepstatin, 1 μm aprotinin, or 4 mM pefabloc in the lysis buffer had no effect on the apparent mass of CHI (data not shown). Antiphosphoserine, antiphosphotyrosine, antiphosphotryptophan, and antiphosphoprotein antibodies also failed to detect immunoprecipitated CHI of either type by immunoblot analysis (data not shown). This suggests that the two forms of CHI are not the result of proteolysis or phosphorylation. Instead, CHI may contain some additional group attached by a bond that is sensitive to reduction by thiols.

Figure 5.

Analysis of the two molecular mass variants of CHI. Samples of plant extracts treated with specific compounds were fractionated by using reducing SDS/PAGE and then assayed for CHI by immunoblot analysis. Time points were taken at 1, 4, or 7 h for plant lysates with and without 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (+/− me). Samples were collected after 30 min of incubation with 1 M Tris, pH 7.2 (T); 0.2 M KOH (OH); 1 M hydroxylamine, pH 7.2 (H); or 5 M 2-mercaptoethanol (me). S, plant lysate, used as a size standard, that contains both molecular mass species of CHI after incubation in buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol for 4 h. The two bands migrate at approximately 31 and 26 kDa relative to molecular mass standards.

A common thiol-sensitive linkage found in proteins is the thioester bond by which moieties like fatty acids are attached to cysteine residues. Thioesters are cleaved rapidly by 1 M hydroxylamine at 25°C (41). It should be noted that hydroxylamine will also specifically hydrolyze Asn-Gly peptide bonds, but only after 9 h at 45°C at a 2 M concentration (42). When hydroxylamine was added to the extraction buffer at a concentration of 1 M, approximately half of the CHI shifted to 26 kDa in 30 min at 25°C (Fig. 5). Incubation for more than 4 h at 25°C was required to obtain the same result with 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. Treatment with 1 M Tris, pH 7.2, or 0.2 M KOH had no effect. These results are consistent with the possibility that CHI is modified with a moiety linked by a thioester bond.

Discussion

Current data suggest that spatial organization is a fundamental aspect of most, if not all, cellular processes. This includes metabolic systems in which catalytic efficiency and control of end-product specificity can be enhanced by the assembly of enzymes into macromolecular complexes. The idea that phenylpropanoid and flavonoid metabolism may involve macromolecular enzyme assemblies can be traced back 35 years to Helen Stafford’s suggestion that this organization might regulate the partitioning of intermediates among competing pathways and determine the intracellular deposition of end products (25, 43). Biochemical data in support of this concept subsequently led to a model suggesting that these pathways are assembled as a linear array of sequential enzymes loosely anchored to the cytoplasmic face of endoplasmic reticulum membranes (29, 33).

We have demonstrated specific interactions among enzymes of flavonoid biosynthesis based on three criteria: activation of multiple reporter genes in a yeast two-hybrid system, extraction of flavonoid enzymes from crude plant protein extracts by CHS- and CHI-affinity chromatography, and coimmunoprecipitation of various flavonoid enzymes with an antibody specific for CHI. The results of the two-hybrid analysis indicate that the Arabidopsis CHS, CHI, and DFR enzymes are involved in specific protein–protein interactions. However, these interactions are detectable only for certain fusion combinations; for example, CHS fused to the Gal41–147 interacts with DFR but not with CHI, whereas CHS fused to Gal4768–881 interacts with CHI but not with DFR. These results suggest that specific protein association domains are masked by the fusion partner in some constructs or that accessibility is affected by the orientations of the proteins relative to each other. These data could indicate that the enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of flavonoids form a globular complex rather than being assembled in a strictly linear array, as hypothesized in the past (32, 33).

The results of affinity chromatography experiments suggested that flavonoid enzymes also interact with each other in plant cells. Recombinant CHS and CHI proteins that were immobilized on resin bound to each other and to F3H from plant lysates. This binding was enhanced for lysates in which the enzyme corresponding to the immobilized ligand was absent as a result of a null mutation, suggesting that the endogenous plant enzymes compete with the immobilized protein for binding of other flavonoid enzymes. Further evidence for association of flavonoid enzymes in plant cells was provided by experiments showing that CHS, CHI, and F3H were coimmunoprecipitated from plant cell lysates by anti-CHI IgY antibodies. This represents direct evidence of protein–protein interactions among enzymes of the flavonoid pathway and, together with the cofractionation experiments of Hrazdina and others (reviewed in ref. 26), provides strong support for the existence of a flavonoid enzyme complex.

We also have found that CHI can exist in two forms of different molecular mass. It is unlikely that the change in mass observed in our experiments was due to proteolysis for several reasons. First, the shift in size occurred in plant extracts even in the presence of a complex mixture of protease inhibitors. Second, although CHI appeared to be more resistant to proteolysis in lysates from the CHS mutant, tt4(85), than in wild-type lysates, CHI still shifted from 31 to 26 kDa in the presence of 2-mercaptoethanol in the mutant (data not shown). Third, the molecular mass shift could be duplicated by hydrolysis of CHI protein with hydroxylamine. A disparity in the size of the CHI protein has been reported in past studies with a variety of plant species (44–47). Although the molecular basis for this size disparity is not known in any of these cases, several authors have attributed it to the binding of phenolics or membranous fragments to the relatively hydrophobic CHI enzyme. Our results suggest that CHI is covalently coupled via a thiol-sensitive linkage, such as a thioester bond, to a specific moiety that decreases its mobility during SDS/PAGE. We have considered the possibility that CHI is posttranslationally modified with long-chain fatty acids such as palmitate (48) that could play a role in controlling the association of CHI with other flavonoid enzymes at the endoplasmic reticulum. Another possibility is that CHI forms thioester linkages with the thiol group of CoA esters, such as malonyl- or coumaroyl-CoA (Fig. 1), as part of a feedback mechanism. The Arabidopsis enzyme contains a total of three cysteines that are potential targets for thiol-sensitive modification. Further studies are underway to examine the possibility that these sites play a previously unsuspected role in controlling enzyme activity or perhaps even the macromolecular organization of flavonoid metabolism.

A better understanding of metabolism within the framework of specifically localized enzyme complexes may provide powerful approaches to engineering new or improved metabolic pathways in living cells. Simple applications of this concept are already yielding impressive results. These include efforts to use recombinant bifunctional enzymes in lieu of difficult synthetic approaches for the commercial production of oligosaccharides (49) and engineering of the polyketide synthase multicatalytic complex for the production of novel antibiotic macrolides (50). There is also an increasing appreciation for defects in enzyme complex assembly in relation to disease, for example, the role of NADH dehydrogenase assembly in hereditary optic neuropathy (51) and assembly of the branched chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase complex in maple syrup urine disease (52). The rational design of metabolic pathways clearly has enormous potential for bioproduction, for engineering metabolic systems for agronomic improvement of plants and animals, and for advances in the elucidation and treatment of disease. The study of tractable systems such as the Arabidopsis flavonoid pathway can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex structural organization of cellular metabolism and the associated regulatory and kinetic implications.

Acknowledgments

This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Paul A. Srere, whose inspiration and encouragement were a vital aspect of this project. We are grateful to Dr. Bill Crosby for providing the two-hybrid vectors and to Matt Stinchcomb and Eric Chen for assistance with the two-hybrid assays. We also thank Bettina Deavours, Mike McConnell, Matt Pelletier, Mike Santos, and Dave Saslowsky for insightful discussions during the course of the project and Dr. Jim Westwood for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (DMB-9304767 and MCB-9808117) and a Sigma Xi Grant-in-Aid-of-Research to I.E.B.

Abbreviations

- CHI

chalcone isomerase

- CHS

chalcone synthase

- DFR

dihydroflavonol reductase

- F3H

flavanone 3-hydroxylase

- TRX

thioredoxin

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Zalokar M. Exp Cell Res. 1960;19:114–132. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(60)90042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kempner E S, Miller J H. Exp Cell Res. 1968;51:141–149. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(68)90164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ovádi J, Srere P A. Cell Biochem Funct. 1996;14:249–258. doi: 10.1002/cbf.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathews C K. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6377–6381. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6377-6381.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sui D, Wilson J E. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;345:111–125. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wojtas K, Slepecky N, von-Kalm L, Sullivan D. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;8:1665–1675. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.9.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan P, Woehl E, Dunn M F. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:22–27. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(96)10066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vélot C, Mixon M B, Teige M, Srere P A. Biochemistry. 1997;36:14271–14276. doi: 10.1021/bi972011j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elcock A H, McCammon J A. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12652–12658. doi: 10.1021/bi9614747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Srere P A. Biol Chem Hoppe–Seyler. 1993;374:833–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McConkey E H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:3236–3240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Srivastava D K. J Theor Biol. 1991;152:93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80518-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shirley B W. Seed Sci Res. 1998;8:415–422. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shirley B W. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;1:377–382. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mol J, Grotewold E, Koes R. Trends Plant Sci. 1998;3:212–217. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koes R E, Quattrocchio R, Mol J N M. BioEssays. 1994;16:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelletier M K, Shirley B W. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:339–345. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.1.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pelletier M K, Murrell J, Shirley B W. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:1437–1445. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.4.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelletier M K, Burbulis I E, Shirley B W. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;40:45–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1026414301100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shirley B W, Hanley S, Goodman H M. Plant Cell. 1992;4:333–347. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burbulis I E, Iacobucci M, Shirley B W. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1013–1025. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.6.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kubasek W L, Shirley B W, McKillop A, Goodman H M, Briggs W, Ausubel F M. Plant Cell. 1992;4:1229–1236. doi: 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubasek W L, Ausubel F M, Shirley B W. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;37:217–223. doi: 10.1023/a:1005977103116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin C, Prescott A, Mackay S, Bartlett J, Vrijlandt E. Plant J. 1991;1:37–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.1991.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stafford H A. Rec Adv Phytochem. 1974;8:53–79. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winkel-Shirley, B. (1999) Physiol. Plant., in press.

- 27.Fritsch H, Grisebach H. Phytochemistry. 1975;14:2437–2442. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stafford H A. In: The Biochemistry of Plants. Conn E E, editor. Vol. 7. New York: Academic; 1981. pp. 117–137. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hrazdina G, Wagner G J. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;237:88–100. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner G J, Hrazdina G. Plant Physiol. 1984;74:901–906. doi: 10.1104/pp.74.4.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hrazdina G, Zobel A M, Hoch H C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8966–8970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hrazdina G, Wagner G J. Annu Proc Phytochem Soc Europe. 1985;25:120–133. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stafford H A. Flavonoid Metabolism. Boca Raton, FL: CRC; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelletier M K, Shirley B W. Plant Physiol. 1995;109:1125–1127. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kohalmi S E, Reader L J V, Samach A, Nowak J, Haughn G W, Crosby W L. Plant Mol Biol Manual. 1998;1:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feilotter H E, Hannon G J, Ruddell C J, Beach D. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1502–1503. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.8.1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gietz R D, Schiestl R H. Methods Mol Cell Biol. 1995;5:255–269. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. New York: Greene & Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cain C C, Saslowsky D E, Walker R A, Shirley B W. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;35:377–381. doi: 10.1023/a:1005846620791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chevray P M, Nathans D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5789–5793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coligan J E, Dunn B M, Ploegh H L, Speicher D W, Wingfield P T. In: Current Protocols in Protein Science. Chanda V B, editor. Vol. 2. New York: Wiley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fontana A, Gross E. In: Practical Protein Chemistry: A Handbook. Darbre A, editor. New York: Wiley; 1986. pp. 68–120. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stafford H A. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1974;25:459–486. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kreuzaler F, Hahlbrock K. Eur J Biochem. 1975;56:205–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb02223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Weely S, Bleumer A, Spruyt R, Schram A W. Planta. 1983;159:226–230. doi: 10.1007/BF00397529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dixon R A, Blyden E R, Robbins M P, van Tunen A J, Mol J N M. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:2801–2808. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Tunen A J, Mol J N. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1987;257:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90545-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dunphy J T, Linder M E. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1436:245–261. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(98)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gilbert M, Bayer R, Cunningham A M, DeFrees S, Gao Y, Watson D C, Young N M, Wakarchuk W W. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:769–772. doi: 10.1038/nbt0898-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marsden A F A, Wilkinson B, Cortes J, Dunster N D, Staunton J, Leadlay P F. Science. 1998;279:199–202. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bai Y, Attardi G. EMBO J. 1998;17:4848–4858. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Danner D J, Doering C B. Front Biosci. 1998;3:d517–d524. doi: 10.2741/a299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]