Abstract

NADPH:protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) oxidoreductase (POR) is the key enzyme of chlorophyll biosynthesis in angiosperms. In barley, two POR enzymes, termed PORA and PORB, exist. Both are nucleus-encoded plastid proteins that must be imported posttranslationally from the cytosol. Whereas the import of the precursor of PORA, pPORA, previously has been shown to depend on Pchlide, the import of pPORB occurred constitutively. To study this striking difference, chimeric precursor proteins were constructed in which the transit sequences of the pPORA and pPORB were exchanged and fused to either their cognate polypeptides or to a cytosolic dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) reporter protein of mouse. As shown here, the transit peptide of the pPORA (transA) conferred the Pchlide requirement of import onto both the mature PORB and the DHFR. By contrast, the transit peptide of the pPORB directed the reporter protein into both chloroplasts that contained or lacked translocation-active Pchlide. In vitro binding studies further demonstrated that the transit peptide of the pPORA, but not of the pPORB, is able to bind Pchlide. We conclude that the import of the authentic pPORA and that of the transA-PORB and transA-DHFR fusion proteins is regulated by a direct transit peptide-Pchlide interaction, which is likely to occur in the plastid envelope, a major site of porphyrin biosynthesis.

One of the fundamental problems of modern cell biology pertains to the question of how nucleus-encoded organelle proteins reach their final destinations (1, 2). This question can be broken down into three major parts. First, what information targets an organelle protein to its proper place? Second, what factors are needed to decode this targeting information? Third, what is the mechanism of translocation across the hydrophobic lipid bilayers (1, 2)?

Much progress has been made to answer these questions for proteins that are destined for either the mitochondria or the endoplasmic reticulum of eukaryotic cells (3–8). In the case of mitochondria, it is the generally accepted view that most cytosolic precursor proteins contain specialized targeting information in their NH2-terminal parts, that these and other parts of the precursor polypeptides interact with cytosolic factors either before or during their binding to receptor components at the mitochondrial outer membrane, and that ATP represents the driving force for the actual translocation step (3–6).

In the case of plastids, NH2-terminal extensions of the cytosolic precursors referred to as the chloroplast transit peptides have been shown to bind to specific receptor components at the outer plastid envelope (see refs. 9 and 10 for reviews). This step requires a low (<50 μM) ATP concentration (11) and, in most cases, is likely to involve some cytosolic helper proteins, such as chaperones, in particular Hsp70, cpn60, and their cognates (12–14). During the actual translocation step, the precursors then move through a putative protein import apparatus in the outer and inner plastid envelope membranes (see ref. 15 for summary).

Cytosolic precursor proteins were long thought to be continuously imported into the plastids (e.g., refs. 9 and 10). Recent evidence, however, suggests that there might be exceptions. For example, the precursor of the NADPH:protochlorophyllide (Pchlide) oxidoreductase (POR) (EC 1.3.1.33) A of barley (pPORA) was found to be transported into isolated plastids in a regulated manner (16, 17). Part of the Pchlide that is synthesized in barley etioplasts, a fraction of the pigment that we call translocation-active Pchlide, triggered the import of the pPORA (16, 17). By contrast, such translocation-active Pchlide was not present in chloroplasts, and hence no import of the pPORA occurred (16, 17). However, when chloroplasts were fed the tetrapyrrole precursor 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) the import of the pPORA could be restored (16, 19).

In this study, we addressed the question of whether the transit sequence or the mature part of the pPORA may regulate the import of the precursor into chloroplasts. We demonstrate that there is a Pchlide binding site in pPORA’s transit peptide that interacts with the pigment and thereby triggers the actual translocation step by which the authentic precursor and two other reporter proteins are imported into the plastids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of Chimeric Precursor Proteins.

Chimeric precursor proteins consisting of the transit peptide of the pPORA (transA) and the mature part of the pPORB, or vice versa, were constructed by a PCR-based approach (18). The DNA sequence encoding transA was generated with primers 1 (5′-GAGAGAGGATCCCCAAGCTCACCGTCATCCATGGCT-3′) and 2 (5′-TATGCCGGATCCGCTCGGCGACGCGGTCGA-3′), that for transB with primers 3 (5′-TATGAGAGAGGATCCTGCTCGCCGGCTCAGATGGCT-3′) and 4 (5′-TATGAGAGAGGATCCGGCCGGCGACGCCGGGGTTGC-3′), using the cDNA clones A7 (19) and L2 (20), respectively, as templates. Similarly, double-stranded DNAs encoding the mature parts of the pPORA (PORA) and pPORB (PORB) were generated by amplification with the primer pair 5 (5′-AACTGCAGATGGGCAAGAAGACGCTGCGGCAG-3′) plus 6 (5′-AACTGCAGGGTGGATCATAGTCCGACGAGCTT-3′), and primer pair 7 (5′-AACTGCAGATGGGCAAGAAGACTGTCCGCACG-3′) plus 8 (5′-AACTGCAGTGATCATGCGAGCCCGACGAGCTT-3′), respectively. After subcloning into the PstI site of pUC19 (New England BioLabs), the DNAs for PORA and PORB were cut out with BamHI and HindIII and inserted into identically treated pSP64 vectors (Promega) (21). Subsequently, the amplified DNAs encoding transA and transB were inserted into the BamHI site of these vectors.

For the construction of transA-dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) and transB-DHFR clones, BamHI-digested DNAs encoding transA and transB were generated as described previously and subcloned in exchange for the DNA of transPC into plasmid pSPPC1–67DHFR, which encodes a chimeric transPC-DHFR protein consisting of the transit peptide of plastocyanin (transPC) of Silene pratensis fused to a cytosolic DHFR of mouse (22). The identity of all of the different clones was confirmed by DNA sequencing, using a T7 DNA sequencing kit (Promega) and the gel system described by Sanger et al. (23).

Import Assay.

Chloroplasts were prepared from light-grown seedlings of barley by Percoll density gradient centrifugation and further purified on Percoll cushions, as described previously (16). Each chloroplast sample was divided into two equal parts. Half was incubated with 5-ALA dissolved in phosphate buffer (16) and ATP to induce the formation of translocation-active Pchlide (17). The other half was incubated with phosphate buffer instead of 5-ALA (17). The different plastid samples then were added to radioactively labeled pPORA, pPORB, transA-PORB, transB-PORA, transA-DHFR, transB-DHFR, and transPC-DHFR molecules that had been synthesized by coupled in vitro transcription/translation (24) of the cDNA clones described previously. [35S]Methionine-labeled precursor molecules that had not been imported into the plastids during a 15-min incubation in the dark and thus remained in the supernatants after centrifugation of the incubation mixtures were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid, separated electrophoretically (25), and detected by autoradiography. Similarly, the radiolabeled mature polypeptides were recovered from thermolysin-treated (26), intact plastids by sonication and precipitation with trichloroacetic acid, run in a separate denaturing polyacrylamide gradient containing NaDodSO4, and detected by autoradiography (25).

Pchlide Binding Assay.

TransA-DHFR, transPC-DHFR, and transB-DHFR fusion proteins were synthesized in vitro, separated by NaDodSO4/PAGE, and detected by autoradiography. The radioactive bands corresponding to the different precursors were excised and quantified by liquid scintillation counting. Taking into account these radioactivities and the specific radioactivity of [35S]methionine, the number of methionine residues per protein molecule, and the volume of translation per reaction, the concentration of the different precursors could be determined. Incubation mixtures containing 0.05, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 μg of the different precursors then were supplemented with Pchlide that was prepared according to ref. 27 and used at a final concentration of 9.18 μg·ml−1. After incubation in the dark for 15 min, the incubation mixtures were subjected to gel filtration of Sephadex G15 to remove excess pigment not bound to the different chimeric precursor proteins (16). Precursor protein-Pchlide complexes running in the flowthrough were extracted with acetone. After an additional step of centrifugation, radiolabeled precursor proteins found in the sediment fraction were separated by NaDodSO4/PAGE and quantified as described above. The level of Pchlide in the supernatant of each of the different samples was determined by fluorescence measurements at an excitation wavelength of 433 nm in a Perkin–Elmer spectrometer LS50. At this excitation wavelength, Pchlide has an emission maximum at 628 nm (16).

RESULTS

Comparison of pPORA and pPORB Reveals Major Differences in Their Transit Peptides.

pPORA and pPORB are structurally related proteins. Their overall amino acid sequence identity is 74.9%, as deduced from corresponding cDNA clones (20). Because pPORA and pPORB are most divergent in their NH2-terminal parts, which start at Met-1 and end at Gly-67 of the pPORA (19), we concluded that their strikingly different import pathways (28) might be due to differences in their transit sequences. We assumed that the transit peptide of the pPORA (transA) might contain a Pchlide-responsive element that would direct the precursor into chloroplasts that contain translocation-active Pchlide. In chloroplasts that lacked translocation-active Pchlide, however, pPORA simply bound to the plastid envelope but was not imported. The precursor passed the plastid envelope membranes only when the arrest of transport was relieved upon production of Pchlide by 5-ALA feeding. Because the transit peptide of the pPORB lacked the Pchlide-responsive element, constitutive protein translocation occurred in both chloroplasts that contain or lack translocation-active Pchlide.

The Transit Peptide of the pPORA (TransA) Is Necessary and Sufficient to Regulate the Import of Proteins into Pchlide-Containing Chloroplasts.

TransA-PORB and transB-PORA fusion proteins synthesized from the recombinant clones described in Materials and Methods were incubated with chloroplasts that had been pretreated with 5-ALA or phosphate buffer alone. To avoid a depletion of energy sources required for the import of the precursors, all incubation mixtures were supplemented with 5 mM ATP.

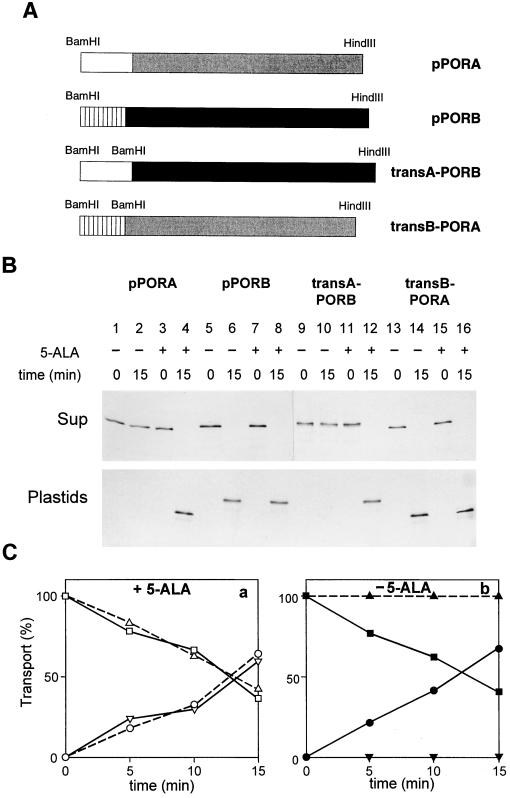

As demonstrated in Fig. 1B, the transA-PORB fusion protein was imported only into chloroplasts that contained the exogenous 5-ALA-derived Pchlide (compare Fig. 1B lanes 11 and 12 to lanes 9 and 10; see also Fig. 1C for quantitation of the import data). By contrast, the transB-PORA fusion protein could be imported into both chloroplasts that contained or lacked Pchlide produced by 5-ALA feeding (Fig. 1B, lanes 13–16; see also Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

The transit peptide of the pPORA (transA) confers the Pchlide requirement of import onto the mature PORB. (A) Schematic presentation of constructed chimeric precursor proteins, as compared with the authentic pPORA and pPORB. (B) Import and processing of the precursor proteins described in A with chloroplasts containing (+) or lacking (−) translocation-active Pchlide produced by 5-ALA feeding. Representative autoradiograms show the different precursor proteins (Sup) and the mature polypeptides (Plastids) before (0) and after a 15-min incubation in the dark. (C) Quantitation of import data, showing the levels of the transA-PORB (▵, ▴) and transB-PORA (□, ▪) precursors, as well as the levels of the mature PORA (○, •) and PORB (▿, ▾) during a time course analysis with chloroplasts containing (▵, □, ○, ▿) or lacking (▴, ▪, •, ▾) the exogenous 5-ALA-derived Pchlide. Percentages refer to the sum of radioactivities found in the supernatant and plastid fractions, respectively, at each of the indicated time points, set as 100.

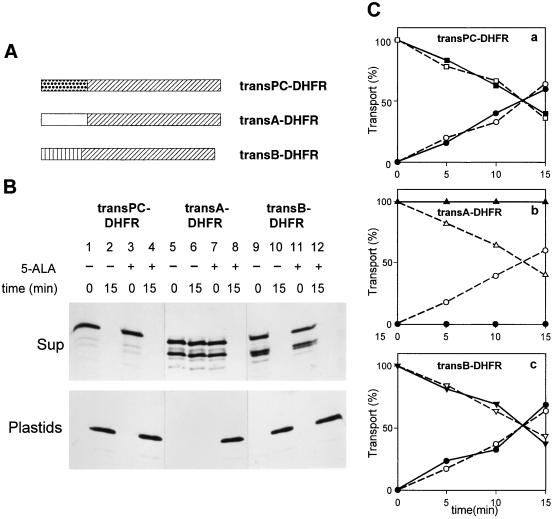

At first glance, these findings implied that the transit peptide of the pPORA regulated the import of the transA-PORB as well as authentic pPORA into Pchlide-containing chloroplasts. However, these results did not demonstrate that this information was, in fact, sufficient for the translocation step to take place. To ultimately show this, the transit peptide of the pPORA was fused to a cytosolic DHFR of mouse (Fig. 2A), and the import of this chimeric transA-DHFR protein was determined with chloroplasts that contained or lacked Pchlide produced by 5-ALA pretreatment.

Figure 2.

TransA directs a cytosolic DHFR reporter protein of mouse into Pchlide-containing, but not Pchlide-free, chloroplasts. (A) Schematic presentation of the constructed chimeric precursor proteins. (B) Import characteristics of the different chimeric precursors into isolated chloroplasts containing (+) or lacking (−) Pchlide produced by 5-ALA feeding. Representative autoradiograms show the different precursor proteins (Sup) and the DHFR (Plastids) before (0) and after a 15-min incubation in the dark. (C) Quantitation of import data, showing the levels of the transPC-DHFR (□, ▪), transA-DHFR (▵, ▴), and transB-DHFR (▿, ▾) chimeric precursors as well as the level of imported DHFR (○, •) during time course analyses with chloroplasts containing (▵, ○, □, ▿) or lacking (▴, •, ▪, ▾) the exogenous 5-ALA-derived Pchlide. Percentages refer to the sum of radioactivities found in the supernatant and plastid fractions, respectively, at each of the indicated time points, set as 100.

Fig. 2B demonstrates that the transit peptide of the pPORA, in fact, conferred the Pchlide requirement of import onto the DHFR (Fig. 2B compare lanes 7 and 8 to lanes 5 and 6; see also quantitative data in Fig. 2C, b, open versus closed symbols). By contrast, the two other chimeric precursors, transB-DHFR, in which the transit peptide of the pPORB had been fused to the DHFR (Fig. 2B, lanes 9–12, and Fig. 2C, c), and transPC-DHFR, consisting of the transit peptide of plastocyanin of Silene pratensis and the NH2-terminally fused DHFR (Fig. 2B, lanes 1–4, and Fig. 2C, a), could be imported into both chloroplasts that contained or lacked the exogenous 5-ALA-derived Pchlide.

TransA Binds Pchlide in Vitro.

On the basis of these findings we concluded that the transit peptide of the pPORA might contain a Pchlide binding site that interacted with the pigment during import. Because coimmunoprecipitation studies that would allow tracing nonprocessed intermediates of transA-DHFR complexed with Pchlide during import into the stroma could not be performed given the lack of commercially available DHFR antibodies, another approach was chosen. TransA-DHFR-Pchlide complexes were reconstituted in vitro and the actual levels of protein and pigment determined for each of the tested precursor concentrations.

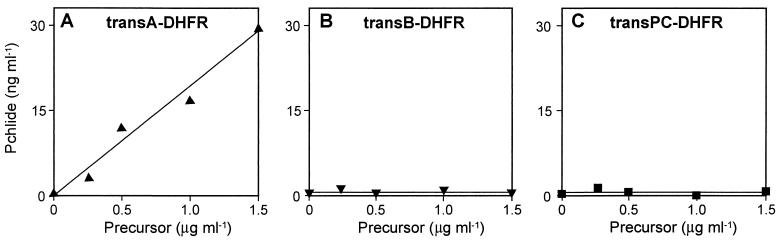

As shown in Fig. 3A, Pchlide binding could indeed be detected with the chimeric transA-DHFR fusion protein. From the quantitation of binding data it turned out that 1 μg of transA-DHFR was able to bind approximately 20 ng of Pchlide. This corresponded to 32.2 pmols of transA-DHFR and 32.6 pmols of Pchlide, respectively, and suggested that there was a 1:1 stoichiometry of transA-DHFR to Pchlide in the recovered transA-DHFR-Pchlide complexes. Neither the transB nor the DHFR moieties, if analyzed as the transB-DHFR fusion protein (Fig. 3B), seemed to be able to bind Pchlide. Similarly, no Pchlide binding was observed with the transPC-DHFR fusion protein (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

TransA binds Pchlide in vitro. TransA-DHFR (A), transB-DHFR (B), and transPC-DHFR (C) synthesized in vitro were incubated with isolated Pchlide, subjected to gel filtration on Sephadex G15, and extracted with acetone. After centrifugation of the acetone extracts, the levels of the precursors recovered in the sediment fractions and of Pchlide present in the supernatant fractions were determined.

DISCUSSION

A conserved sequence element, termed the heme regulatory motif, previously has been identified in the presequence of preALA synthase, which is a key enzyme of heme biosynthesis, and shown to regulate its import into mitochondria of mouse (29). In the present study, a different mode of regulation of protein translocation by a porphyrin pigment was discovered. Pchlide was shown to bind to the transit peptide of the pPORA and to trigger the translocation of the cytosolic precursor into chloroplasts.

From a mechanistic point of view, the regulation of mitochondrial protein import by heme and of plastid import by Pchlide hence must be strikingly different. Whereas heme binding in the cytosol inhibited the receptor binding and/or translocation step(s) of preALA synthase (29), the interaction between Pchlide and the pPORA, as shown in this study, was required for the import of this particular precursor protein to take place. Whereas the heme regulatory motif has been demonstrated to occur in numerous other proteins (29, 30) and shown to be the target through which heme also controls other cellular processes, such as transcription and translation (30–32), the identity of the Pchlide regulatory motif in pPORA’s transit peptide remains to be determined.

Based on sequence comparison and the obvious lack of relationship to the numerous other proteins that are known to bind porphyrins, such as heme and chlorophyll (32, 33), we conclude that the Pchlide regulatory motif must represent a distinctive pigment binding motif. Because part of the Pchlide present in spinach chloroplasts previously has been shown to be synthesized in the plastid envelope (34), it is tempting to speculate that the interaction between this translocation-active pigment and the transit peptide triggered the initial step of import of the pPORA into chloroplasts, whereas later steps were presumably driven by ATP hydrolysis (35).

The model of Pchlide-dependent translocation through direct transit peptide-pigment interaction implies that, in the absence of Pchlide, pPORA first may become partially translocated into the import apparatus. How and why the precursor then stops its translocation is not yet known. Nevertheless, one may assume that the transit peptide might contain a stop-transfer sequence that caused the arrest of precursor translocation and that Pchlide, through its binding to the porphyrin binding site, relieved this block of import. Whether the import machineries in the outer or inner plastid envelope membranes are the site of control is as yet undetermined. We very much hope to identify this site and to determine whether pPORA uses the same translocation machineries that are used by all of the other cytosolic plastid precursor proteins, or whether there might be a distinct site of protein translocation in the plastid envelope that is devoted to specifically sequestering the pPORA.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Dr. P. Weisbeek, The University of Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands, for a gift of plasmid pSPPC1–67DHFR. Expert photography work by Dr. D. Rubli (Zurich) is gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by a research project grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (to S.R. and K.A.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- Pchlide

protochlorophyllide

- POR

NADPH:Pchlide oxidoreductase

- transA

transit peptide of the pPORA

- 5-ALA

5-aminolevulinic acid

- DHFR

dihydrofolate reductase

- transPC

transit peptide of plastocyanin

References

- 1.Siegel V. Cell. 1995;82:167–170. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schatz G, Dobberstein B. Science. 1996;271:1519–1526. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfanner N, Rassow J, van der Klei I J, Neupert W. Cell. 1992;68:999–1002. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90069-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lill R, Neupert W. Trends Cell Biol. 1996;6:56–61. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)81015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shore G C, McBride H M, Millar D G, Steenaart N A E, Nguyen M. Eur J Biochem. 1995;227:9–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfanner N, Craig E A, Meijer M. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:368–372. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90113-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rapoport T A. Science. 1992;258:931–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1332192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders S L, Schekman R. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13791–13794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Archer E K, Keegstra K. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1990;22:789–810. doi: 10.1007/BF00786931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cline K, Henry R. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:1–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen L J, Theg S M, Selman B R, Keegstra K. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6724–6729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waegemann K, Paulsen H, Soll J. FEBS Lett. 1990;261:89–92. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimm R, Speth V, Gatenby A A, Schäfer E. FEBS Lett. 1991;286:155–158. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80963-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinbothe S, Reinbothe C, Neumann D, Apel K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:12026–12030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnell D J. Cell. 1995;83:521–524. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reinbothe S, Runge S, Reinbothe C, van Cleve B, Apel K. Plant Cell. 1995;7:161–172. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinbothe S, Reinbothe C, Runge S, Apel K. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:299–308. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Innis M A, Gelfand D H, Sninsky J J, White T J, editors. PCR Protocols. San Diego: Academic; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz R, Steinmüller K, Klaas M, Forreiter C, Rasmussen S, Hiller C, Apel K. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;217:355–361. doi: 10.1007/BF02464904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holtorf H, Reinbothe S, Reinbothe C, Bereza B, Apel K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3254–3258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Plainview, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hageman J, Baecke C, Ebskamp M, Pilon R, Smeekens S, Weisbeek P. Plant Cell. 1990;2:479–494. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.5.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanger F, Nickler S, Coulson A R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krieg P A, Melton D A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:7057–7070. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.18.7057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli U K. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cline K, Werner-Washburne M, Andrews J, Keegstra K. Plant Physiol. 1984;75:675–678. doi: 10.1104/pp.75.3.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffiths W T. Biochem J. 1978;174:681–692. doi: 10.1042/bj1740681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinbothe S, Reinbothe C, Holtorf H, Apel K. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1933–1940. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.11.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lathrop J T, Timko M P. Science. 1993;259:522–525. doi: 10.1126/science.8424176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L, Guarente L. EMBO J. 1995;14:313–320. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07005.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Padmanaban G, Venkateswar V, Rangarajan P N. Trends Biochem Sci. 1989;14:492–496. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(89)90182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bock K W, De Matteis F, Aldridge W N, editors. Heme and Hemoproteins. New York: Springer; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dolganov N A, Bhaya D, Grossman A R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:636–640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joyard J, Block M, Pineau B, Albrieux C, Douce R. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:21820–21827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Theg S M, Bauerle C, Olsen L J, Selman B R, Keegstra K. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:6730–6736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]