Abstract

The accumulation of β-amyloid peptides (Aβ) into senile plaques is one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer disease. Aggregated Aβ is toxic to cells in culture and this has been considered to be the cause of neurodegeneration that occurs in the Alzheimer disease brain. The discovery of compounds that prevent Aβ toxicity may lead to a better understanding of the processes involved and ultimately to possible therapeutic drugs. Low nanomolar concentrations of Aβ1-42 and the toxic fragment Aβ25-35 have been demonstrated to render cells more sensitive to subsequent insults as manifested by an increased sensitivity to formazan crystals following MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) reduction. Formation of the toxic β-sheet conformation by Aβ peptides is increased by negatively charged membranes. Here we demonstrate that phloretin and exifone, dipolar compounds that decrease the effective negative charge of membranes, prevent association of Aβ1-40 and Aβ25-35 to negatively charged lipid vesicles and Aβ induced cell toxicity. These results suggest that Aβ toxicity is mediated through a nonspecific physicochemical interaction with cell membranes.

β-amyloid, the major constituent of senile plaques in Alzheimer disease patients (1) has been proposed to be the cause of the neurodegeneration that occurs in Alzheimer disease brains. Aβ1-42, Aβ1-40, and certain fragments, notably Aβ25-35, are directly toxic to neuronal cell cultures at high micromolar concentrations (2–5). The observed cell death has been correlated with an effect of amyloid peptides on the membrane integrity as determined by lipid peroxidation (2). Furthermore, it has recently been shown that low nanomolar concentrations of Aβ peptides increase the susceptibility of the plasma membrane to additional insults (6).

Substantial evidence has been provided suggesting that a crucial step for the formation of toxic Aβ is the transition of random coil to β-sheet conformation that is necessary for fibril aggregation. Those fibrils have been demonstrated to cause cell death (7–9). On the other hand studies with lipid vesicles demonstrated that formation of β-sheet structures is enhanced in the presence of negatively charged lipid vesicles (10–12). Decreasing the negative charge of a membrane may, therefore, result in a decrease in membrane association of Aβ peptides. Such a decrease in the negative charge of lipid membranes by a decrease in the membrane dipole potential has been demonstrated for phloretin, a lipophilic dipolar substance shown to decrease the membrane dipole potential (13–15).

Here we demonstrate that phloretin and a structural analogue, exifone, not only reduce the association of toxic Aβ peptides with the membrane but also prevent Aβ toxicity to neuron-like PC12 cells. These results suggest that a physicochemical interaction of Aβ peptides with negatively charged membranes might be responsible for the toxic effect of Aβ to neuronal cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Rat PC12 pheochromocytoma cells were a gift from E. Shooter (Stanford, CA). DMEM, penicillin-streptomycin, N2-mix (16), and horse serum were purchased from Life Technologies (Inchinnan Business Park, U.K.). Fetal bovine serum was purchased from HyClone. The CytoTox kit was obtained from Promega, and fatty acid-free BSA was from Boehringer Mannheim. MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) and phloretin 2′,4′,6′-trihydroxy-3-(p-hydroxyphenyl)propiophenone were purchased from Sigma; Aβ1-40 and Aβ25-35 were from Bachem Feinchemikalien (Bubendorf, Switzerland). Aβ1-42 fibrils were prepared by H. Doebeli (Hoffmann–LaRoche, Basel) (7). Stock solutions of Aβ peptides were prepared as follows: Aβ25-35 was dissolved in water at a final concentration of 1 mM. Aβ1-40 was dissolved in water and diluted to 250 μM with PBS. Aβ1-42 fibrils were obtained at 70 μM in 12 mM Tris (pH 8.0). All three peptide solutions were stored in aliquots at −20°C. Exifone was a gift from Pharmascience (Courbevoie, France). 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol (POPG) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids.

Cell Culture.

Rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells were propagated in DMEM containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 10% fetal calf serum, and 5% horse serum in a humidified incubator at 8% CO2.

MTT Reduction.

PC12 cells were plated at a density of 4,000 cells/well on 96-well plates in 50 μl DMEM containing N2 (16) and 0.01% fatty acid-free BSA. After 24 hr Aβ peptides were added at the concentration indicated and cells were incubated for additional 24 hr. MTT was added at a final concentration of 0.15 mg/ml for the appropriate period of time. To determine MTT reduction, the reaction was stopped by addition of isopropanol/HCl. Formazan precipitates were dissolved overnight and absorption was determined at 595 nm. Experiments were done in six replica, and standard deviation did not exceed 3%.

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release.

Floating PC12 cells were spun down, 50 μl of the supernatants were transferred into new wells, and LDH was determined using the CytoTox kit (Promega) as described by the manufacturer. Experiments were done in six replica, and standard deviation did not exceed 10%. The baseline was determined in control assays and subtracted. For samples from MTT pretreated cells, control medium contained MTT. The produced formazan did not interfere with the LDH reaction.

Lipid Vesicles.

About 40 mg of lipid dissolved in chloroform (20 mg/ml) were mixed in the appropriate molar ratio POPC/POPG (75:25, mol/mol). The solvent was evaporated under a nitrogen stream. Lipids were dissolved again in dichloromethane and the solvent was removed with a nitrogen stream to form a thin lipid film. The lipid film was dried overnight under vacuum. Buffer was added to the dry lipid film to get a lipid concentration of 40 mM. The lipid dispersion was vortex mixed and then sonicated under a nitrogen atmosphere for about 10 min, at 10°C, until an almost clear solution was obtained. This leads to the formation of unilamellar vesicles of about 30 nm diameter. Metal debris from the Titanium tip was removed by centrifugation in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 5 min. For incorporation of phloretin or exifone into lipid vesicles, these two substances were dissolved in dichloromethane/methanol (5:1, vol/vol) and (3.75:1, vol/vol), respectively, at a concentration of about 5 mM. Defined amounts of phloretin or exifone were added to the lipid solution in chloroform to obtain the indicated molar ratios. Unilamellar vesicles were prepared as described above.

High Sensitivity Titration Calorimetry.

Isothermal titration calorimetry was performed with a Omega MC-2 instrument from Microcal (Northampton, MA) (17). The calorimeter was calibrated electrically. Solutions were degassed under vacuum prior to use. Lipids vesicles were injected in 10 μl increments into Aβ peptide solution (cell volume, 1.3353 ml). Control experiments were performed with injections of lipid vesicles into buffer without peptide. All experiments were done at 28°C. The starting solutions in the calorimeter cell and in the injection syringe were at the same temperature. The titrations were made at pH of 5.0 to ensure a β-sheet conformation of the amyloid peptides.

RESULTS

Pretreatment of PC12 cells for 24 hr with equipotent concentrations of Aβ peptides—e.g., 1 μM Aβ25-35, 300 nM Aβ1-40, or 150 nM Aβ1-42 (Fig. 1A)—decreased cellular MTT reduction by ≈65%. If cells were treated with phloretin for 60 min prior to addition of MTT, inhibition of MTT reduction by amyloid peptides was prevented in a concentration-dependent manner. Maximal protection was observed at 30 μM phloretin, while 300 μM phloretin was itself toxic for the cells (data not shown). As predicted, inhibition of MTT-dependent LDH release (6) was also observed at concentrations between 10 and 100 μM phloretin. Determination of the kinetics of MTT-dependent LDH release and MTT reduction showed that pretreatment with 30 μM phloretin prevented the amyloid induced LDH release and the concomitant inhibition of MTT reduction (Fig. 2 A and B).

Figure 1.

Effect of phloretin and exifone on Aβ peptide induced inhibition of MTT reduction. PC12 cells were treated for 24 hr with 1 μM Aβ25-35 (▪), 300 nM Aβ1-40 (▴), 150 nM Aβ1-42 (•), or solvent (□). (A) Cells were treated with increasing concentrations of phloretin for the final 60 min or (B) simultaneously for 24 hr with increasing concentrations of exifone. Increasing the pre-incubation time with phloretin to 24 hr resulted in toxic effects at lower concentrations (data not shown). MTT was added for 5 hr. Mean values ± SD are shown.

Figure 2.

Effect of phloretin and exifone on the kinetics of Aβ1-40-induced MTT-dependent LDH release and MTT reduction. PC12 cells were incubated with 300 nM Aβ1-40 for 24 hr and treated either with 30 μM phloretin for 60 min (A and B) or 10 μM exifone for 24 hr (C and D). The time-course of MTT reduction (B and D) and LDH release (A and C) was determined. ○, Control; •, amyloid treated; ▵, control with phloretin/exifone; ▴ amyloid-treated with phloretin/exifone. Mean values ± SD are shown.

Phloretin has been described to interfere with several cellular processes—e.g., inhibition of glucose transport (18), inhibition of potassium channels (19, 20), reduction of colloid osmosis after membrane lesion (21), and reduction of the membrane dipole potential (13–15). Neither phloridizin or dipyridamole, inhibitors of glucose transport (22), nor inhibitors of potassium channels, such as 4-aminopyridine, tetraethylamine, or dendrodotoxin, prevented amyloid toxicity (Table 1). However, phenolphthalein, which has been described to prevent colloid osmosis, and exifone, which is structurally similar to phloretin, also prevented amyloid-dependent inhibition of MTT reduction (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inhibition of amyloid-induced decrease in MTT reduction

| Treatment | Inhibition, % of control |

|---|---|

| 150 nM Aβ1-42 | 100 |

| + Phloretin, 30 μM | 2 |

| + Phloridizin, 1 mM, 24 hr | 87 |

| + Dipyramidole, 5 μM, 1 hr | 72 |

| + 4-Aminopyridine, 1 mM, 24 hr | 85 |

| + Tetraethylammonium, 4 mM, 1 hr | 114 |

| + Dendrodotoxin, 280 nM, 24 hr | 100 |

| + Phenolphthalein 50 μM, 1 hr | −47 |

| + Exifone, 30 μM, 24 hr | 25 |

PC12 cells were treated for 24 hr with 150 nM Aβ1-42, and compounds were added prior to MTT for the time indicated. Inhibition of amyloid-induced decrease in MTT reduction is calculated as % of control: 100% = ΔOD 595 nm (MTT reduction in control cells − MTT reduction in amyloid treated cells). Negative values represent reduction higher than in control cells.

Exifone was found to be less toxic to PC12 cells than phloretin and therefore exifone and amyloid were added to the cells simultaneously (Fig. 1B). Under these conditions exifone prevented the toxicity of Aβ25-35, Aβ1-40, and Aβ1-42. Maximal prevention of amyloid toxicity was observed at 10 μM exifone. Addition of 100 μM exifone was toxic for PC12 cells when incubated for 24 hr (data not shown). Exifone, similar to phloretin, prevented the amyloid-induced MTT-dependent LDH release, thereby preventing the inhibition of MTT reduction (Fig. 2 C and D). High micromolar concentrations of Aβ peptides have been shown previously to induce lysis of PC12 cells indicated by release of intracellular enzymes (5). Simultaneous addition of exifone (30 μM) with Aβ25-35 (100 μM) prevented the release of LDH from PC12 cells (data not shown).

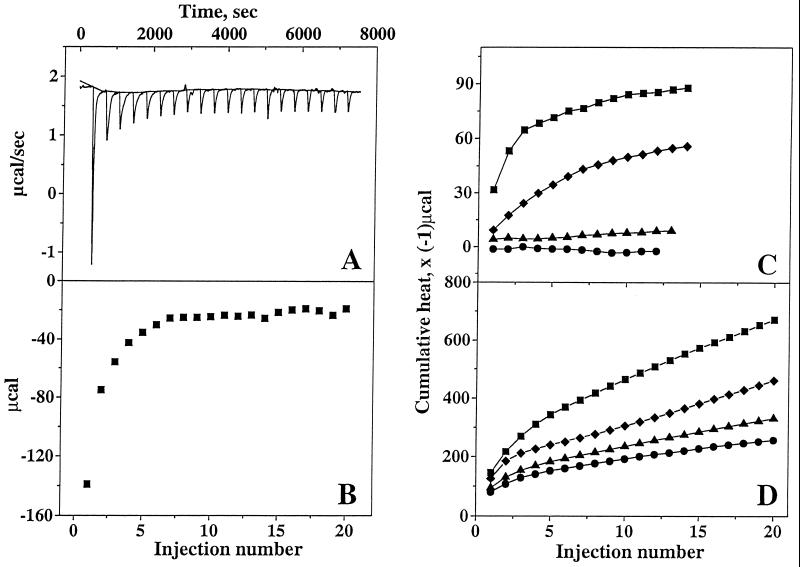

Phloretin has been demonstrated to reduce the membrane dipole potential (13) when incorporated into lipid vesicles, and amyloid association with membranes has been shown to be an ionic interaction rather than a hydrophobic interaction (10, 11). Therefore, the effect of phloretin on the binding of amyloid to negatively charged lipid vesicles was investigated. The peptide–membrane binding was analyzed using high-sensitivity titration calorimetry. As shown in Fig. 3A, small unilamellar lipid vesicles containing 25% (mol/mol) of negatively charged lipid were injected into a diluted Aβ1-40 solution. Each injection elicited a heat of reaction (hi), defined by the area underneath each peak. The heat of reaction decreased with consecutive lipid injections as less and less peptide was available for binding (Fig. 3B). In control experiments, lipid vesicles were injected into pure buffer and a small endothermic reaction of constant amplitude was observed. The corresponding heats of reaction were subtracted in the final analysis. Calorimetric titrations of Aβ25-35 and Aβ1-40 were also performed with unilamellar lipid vesicles containing phloretin and exifone. Fig. 3 C and D summarize the cumulative heat of reaction, Σhi, for the reaction of Aβ25-35 and Aβ1-40, respectively, with the different vesicles. For Aβ25-35 the cumulative heat of reaction reached a plateau value, indicating that all peptide was bound to lipid vesicles (Fig. 3C). In contrast, a complete binding of Aβ1-40 was not reached, even after 20 injections (Fig. 3D) and the total heat of binding reaction was estimated by extrapolation. Phloretin pretreatment of lipids (10% mol/mol) almost completely prevented binding of Aβ25-35 to lipid vesicles. At 0.5% exifone per mol of lipid, exifone completely prevented the binding of Aβ25-35 to lipid membrane, whereas phloretin at this concentration reduced binding by ≈36% (Fig. 3C). Exifone and phloretin at 0.5% per mol of lipid were slightly less effective in preventing binding of Aβ1-40 to lipid vesicles, reducing the binding by ≈62% and 50%, respectively (Fig. 3D). At the same concentration exifone is more efficient than phloretin to prevent amyloid peptides binding to lipid membrane.

Figure 3.

Titration calorimetry. (A) Titration calorimetry of Aβ1-40 (30 μM) with small unilamellar lipid vesicles. Each peak corresponds to the injection of 10 μl of lipid dispersion into the calorimeter cell containing Aβ1-40. (B) Evaluation of the heat of reaction from the area under each peak. (C and D) Cumulative heats of reaction deduced from calorimetric titrations of Aβ25-35 (50 μM) (C) and from calorimetric titrations of Aβ1-40 (30 μM) (D) with small unilamellar lipid vesicles [lipid composition POPC/POPG (75:25, mol/mol), lipid concentration 40 mM (▪)], with phloretin-pretreated lipid vesicles [phloretin/lipid, 1:10, mol/mol (▴), or phloretin/lipid, 0.5:100, mol/mol (⧫)], and with exifone-pretreated lipid vesicles [exifone/lipid, 0.5:100, mol/mol (•)]. Measurements were performed in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) at 28°C.

DISCUSSION

The present results demonstrate that phloretin decreases the susceptibility of the plasma membrane to the damage induced by Aβ peptides. Phloretin and its analogue, exifone, not only reduced the toxicity of Aβ peptides but also prevented the association of Aβ peptides with negatively charged lipid vesicles.

Phloretin has been reported to interfere with a number of membrane-associated processes, which is probably due to the described decrease in the membrane dipole moment (13). These processes include inhibition of glucose transport (18), inhibition of potassium channels (20), protection against electroporation (21), and inhibition of translocation of protein kinase C (23). The present results demonstrate that neither inhibition of glucose transport by the structurally unrelated phloridizin or cytochalasin B (data not shown), nor inhibition of potassium channels (Table 1) prevent Aβ toxicity. In contrast, phenolphthalein, which had been described as protecting against electroporation (21), also protected against Aβ toxicity. Protection against electroporation is most likely related to the reported decrease in the membrane dipole moment, suggesting that this is also the underlying cause for the observed prevention of binding of Aβ peptides to membranes.

As described earlier (10–12), Aβ peptides associate with negatively charged lipid vesicles in a saturable manner, suggesting a protein independent binding of Aβ peptides to membrane lipids. This Aβ–membrane interaction may cause at least some of the cellular events described in response to Aβ peptide treatment, including the reported production of reactive oxygen species in neuronal (2) and in microglia cells (24). Such a nonselective fibril/lipid mechanism of action is further supported by the observation that all-D-enantiomers of Aβ exhibit similar biological properties as the all-L-enantiomers (25). In addition to this interaction of Aβ peptides with the membrane lipids, binding of amyloid peptides to two protein receptors, receptor for advanced glycation (RAGE) (26) and scavenger receptor (SR) (27), has been described. These receptors may enhance the described toxic effects in those cells that express them.

Prevention of the well-described toxic effects of Aβ peptides on primary cultures of neuronal cells and cell lines can be obtained at several key points of the toxic pathway of amyloid peptides. Polyanionic compounds, such as congo red (9) and rifampicin (28) are thought to interfere with the formation of the toxic fibrils, while antioxidants capture reactive oxygen species produced in response to Aβ treatment (29).

The results presented here indicate an additional mechanism of interaction. Polyhydroxylated aromatic compounds like phloretin will prevent amyloid toxicity at the site of action of amyloid, namely the plasma membrane. The calorimetric determination of the association of Aβ peptide fibrils with lipid vesicles demonstrated that this is most probably due to inhibition of the association of Aβ peptide fibrils with the plasma membrane, thereby preventing the amyloid-induced alterations of the membrane and ultimately cell death. These studies indicate that drugs which interfere with this Aβ–membrane interaction have protective effects against amyloid toxicity in vitro. If this toxicity contributes to the neurodegeneration that occurs in Alzheimer disease patients, drugs that interfere with this process could represent a possible neuroprotective strategy.

ABBREVIATIONS

- MTT

(3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- phloretin

2′,4′,6′-trihydroxy-3-(p-hydroxyphenyl) propiophenone

- POPC

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- POPG

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

References

- 1.Mullan M, Crawford F. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:398–402. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Behl C, Davis J B, Lesley R, Schubert D. Cell. 1994;77:817–826. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Busciglio J, Lorenzo A, Yankner B A. Neurobiol Aging. 1992;13:609–612. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(92)90065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loo D T, Copani A, Pike C J, Whitemore E R, Walencewicz A J, Cotman C W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7951–7955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shearman M S, Ragan C I, Iversen L L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1470–1474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hertel C, Hauser N, Schubenel R, Seilheimer B, Kemp J A. J Neurochem. 1996;67:272–276. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67010272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doebeli H, Draeger N, Huber G, Jakob P, Schmidt D, Seilheimer B, D, Wipf B, Zulauf M. Biotechnology. 1995;13:988–993. doi: 10.1038/nbt0995-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soto C, Castano E M, Frangione B, Inestrosa N C. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3063–3067. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorenzo A, Yankner B A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12243–12247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terzi E, Hölzemann G, Seelig J. J Mol Biol. 1995;252:633–642. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seelig J, Lehrmann R, Terzi E. Mol Membr Biol. 1995;12:51–57. doi: 10.3109/09687689509038495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaurin J, Chakrabartty A. Eur J Biochem. 1997;245:355–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-2-00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bechinger B, Seelig J. Biochemistry. 1991;30:3923–3929. doi: 10.1021/bi00230a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jo E, Boggs J M. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1195:245–251. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franklin J C, Cafiso D S. Biophys J. 1993;65:289–299. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81051-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bottenstein J E, Sato G H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:514–517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiseman T, Williston S, Brandts J F, Lung-Nan L. Anal Biochem. 1989;179:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson J A, Falk R E. Anticancer Res. 1993;13:22930–22939. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersen O S, Finkelstein A, Katz I, Cass A. J Gen Physiol. 1976;67:749–771. doi: 10.1085/jgp.67.6.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koh D S, Reid G, Vogel W. Neurosci Lett. 1994;165:167–170. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90736-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deuticke B, Lütkemeier P, Poser B. Biochim Biopys Acta. 1991;1067:111–122. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Czech M P. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:2905–2910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Ruecker A A, Han-Jeon B G, Wild M, Bidlingaier F. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;163:836–842. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meda L, Cassatella M A, Szendrei G I, Otvos Jr L, Baron P, Villalba M, Ferrari D, Rossi F. Nature (London) 1995;374:647–650. doi: 10.1038/374647a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cribbs D H, Pike C H, Weinstein S L, Velasquez P, Cotman C W. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7431–7436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan S D, Chen X, Fu J, Chen M, Zhu H, Roher A, Slattery T, Zhao L, Nagashima M, Morser J, Migheli A, Nawroth P, Stern D, Schmidt A M. Nature (London) 1996;382:685–691. doi: 10.1038/382685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El Khoury J, Hickman S E, Thomas C A, Cao L, Silverstein S C, Loike J D. Nature (London) 1996;382:716–719. doi: 10.1038/382716a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomiyama T, Shoji A, Kataoka K, Suwa Y, Asano S, Kaneko H, Endo N. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6839–6844. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Behl C, Davis J, Cole G M, Schubert D. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;186:944–950. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90837-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]