Abstract

The objective of this study was to apply cine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using displacement encoding with stimulated echoes (DENSE) to measure the dynamic two-dimensional (2D) displacement and Lagrangian strain fields in the biceps brachii muscle. Six healthy volunteers underwent cine DENSE MRI during repeated elbow flexion against the load of gravity. Displacement encoded dynamic images of the upper arm were acquired with spatial and temporal resolutions of 1.9 × 1.9 mm2 and 30 ms, respectively. Pixel-wise Lagrangian displacement and strain fields were calculated from the measured images. We extracted first and second principal strains (E1 and E2) along the centerline and anterior regions of the muscle. E1 and E2 were relatively uniform along the anterior region. However, E1 and E2 were both nonuniform along the centerline region – normalized values for E1 and E2 varied over the ranges of 0.27 to 1.35, and 0.45 to 2.36, respectively. The directions of the first and second principal strains varied throughout the muscle and showed that the direction of principal shortening is not necessarily aligned with fascicle direction. This study demonstrates the utility of cine DENSE MR imaging for analyzing skeletal muscle mechanics and provides data describing the in vivo mechanics of muscle tissue to a level of detail that has not been previously possible.

Keywords: muscle mechanics, biceps, displacement, strain, DENSE, MRI

1. Introduction

Mathematical models of skeletal muscle are widely used to investigate the causes of movement abnormalities and to analyze surgical treatments. Most models represent muscle properties using simple geometric idealizations that assume that all muscle fibers shorten uniformly (Delp et al., 1990; Zajac, 1989). These simplified models are limited in their ability to accurately represent the in vivo behavior of muscles that have complex arrangements of muscle fibers. Recently, several investigators have developed finite-element models of skeletal muscle that allow for representation of realistic three-dimensional (3D) geometries, incorporate the nonlinear active and passive constitutive properties of muscle tissue, and are able to characterize non-uniform shortening within muscles (Blemker and Delp, 2005; Fernandez et al., 2005; Yucesoy et al., 2002). These models have provided new insights into skeletal muscle mechanics; for example, analysis of a finite element model of the biceps brachii muscle identified how complex features of muscle architecture could contribute to non-uniform strains along muscle fascicles (Blemker et al., 2005).

In order to broaden the utility of finite-element muscle models, methods to rigorously validate predictions made by the models are needed. Dynamic magnetic resonance (MR) imaging techniques have made it possible to characterize in vivo motion and shortening of skeletal muscle tissue during joint movement. For example, cine phase-contrast (cine-PC) magnetic resonance images taken of the long head of the biceps brachii showed non-uniform shortening along some muscle fascicles during low-load elbow flexion (Pappas et al., 2002). In that study, the displacements of square regions of interest were calculated by integrating the velocity measurements, and one-dimensional strains were determined by calculating the change in length between square regions that were placed along the muscle fascicles. These data provide valuable in vivo measurements to confirm the models' predictions of non-uniform strains along fascicles. However, in addition to non-uniform shortening along muscle fascicles, finite-element models also predict non-uniform strains transverse to the fascicle direction (Blemker et al., 2005) – results that may have important implications on muscle function, but must be verified with imaging techniques that enable measurements of two-dimensional (2D) strain fields.

MR imaging using displacement encoding with stimulated echoes (DENSE) offers a robust method for quantifying two-dimensional strain fields (Aletras et al., 1999a; Aletras et al., 1999b; Aletras and Wen, 2001; Kim et al., 2004). Relative to an initial displacement-encoding time, DENSE directly encodes tissue displacement into the phase of the stimulated echo. A sequence of phase-reconstructed images are obtained using cine DENSE MR imaging to achieve pixel-wise spatial resolution and direct extraction of tissue displacements. Based on the pixel-wise displacement measurement, two-dimensional Lagrangian strain fields can be calculated (Spottiswoode et al., 2007). Using a motion phantom, cine DENSE has previously been shown to be highly accurate (Spottiswoode et al., 2007). Cine DENSE has also been validated in vivo for myocardial function evaluation (Kim et al., 2004; Gilson et al., 2004).

The goal of this study was to apply cine DENSE MR imaging to measure pixel-wise displacement and Lagrangian strain fields of skeletal muscle. With cine DENSE MR imaging, two- and three-dimensional pixel-wise displacements were measured within the upper arm during active elbow flexion against the load of gravity. To test the technique with existing published results, we extracted one-dimensional strains along the centerline and anterior regions of the muscle and compared these results to cine phase-contrast imaging results, described by Pappas et al. (2002). We then analyzed the two-dimensional strain fields – we determined the values and directions of the first and second principal strains (E1 and E2) along the centerline and anterior regions of the biceps brachii muscle. This study demonstrates the utility of cine DENSE MR imaging for analyzing skeletal muscle mechanics and provides data describing the in vivo mechanics of muscle tissue to a level of detail that has not been previously possible.

2. Methods

2.1. Volunteer Imaging

Six healthy subjects (4 male and 2 female, age 24.4 ± 1.14 yr, height 1.81 ± 0.13 m, weight 74.93 ± 12.67 kg) volunteered for participation in this study. Each subject was scanned using a 1.5T Avanto scanner (Siemens Medical solutions, Erlangen, Germany) after informed consent was obtained. All studies were performed in accordance with the general investigational magnetic resonance imaging/spectroscopy protocol (IRB-HSR #9039) approved by our institutional review board.

The subjects were positioned supine in the MRI bore, allowing them to perform a full range of elbow flexion-extension (Fig. 1). Each subject's dominant arm was aligned with the longitudinal axis of the scanner, and imaged using a general-purpose flexible radio-frequency receive coil. The subject used the hand of the dominant arm to hold the handle of a triggering device attached to the table, and performed active elbow flexion against the load of the handle and the weight of the forearm and hand, from nearly full elbow extension to 45°-90° of elbow flexion at a rate of 30 cycles/min (i.e. 2 seconds between each trigger). The subjects were instructed not to bend their wrist joints while performing the elbow flexion. The subject's upper arm was secured to the table with Velcro straps to ensure that it remained stationary during acquisition. Image acquisition was gated to the onset of elbow flexion using a photodiode circuit. The whole scenario of the study was similar to that described by Pappas et al. (2002). Whenever possible, the imaging parameters were chosen to be the same as those in the study by Pappas et al. (2002), so that a good comparison between these two studies could be made.

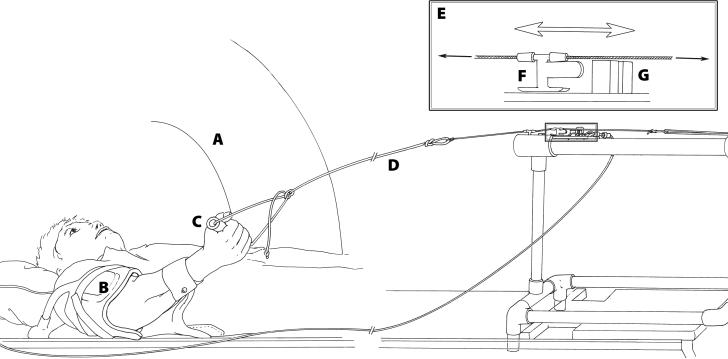

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup. The subject was positioned supine in the MRI scanner (A), and a general-purpose flexible radiofrequency receive coil (B) was wrapped around the upper arm. The subject flexed and extended his/her elbow while grasping a handle (C) that was connected via a rope (D) to the triggering mechanism (E). The triggering mechanism consisted of a light emitting diode (LED) and a photodiode that were mounted to blocks (G) on either side of a slider (F). As the subject flexed his/her elbow, the slider moved past the blocks, which allowed the photodiode to detect the LED signal and send a square pulse to the MRI scanner to indicate the beginning of a motion cycle.

2.2. Image Acquisition

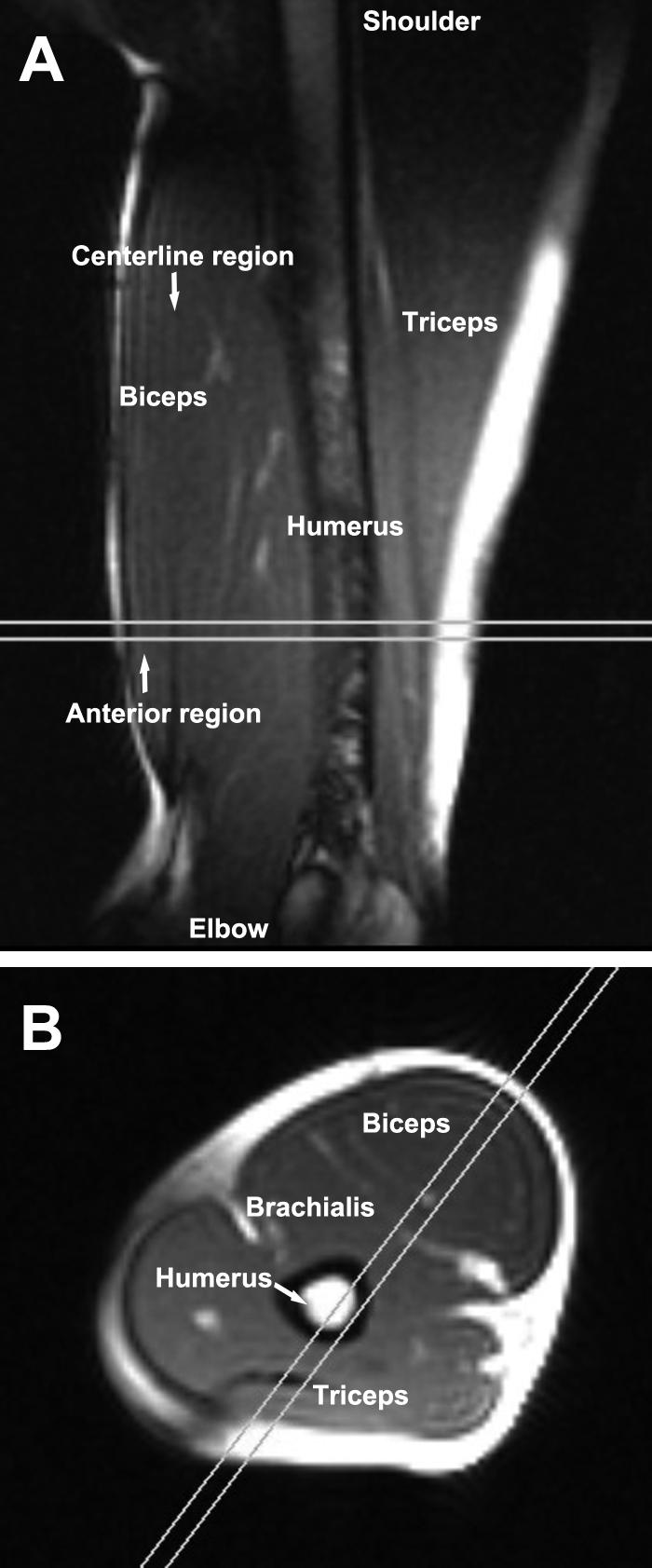

High-resolution static axial images were acquired using a balanced steady state free precession (SSFP) sequence with the arm in the extended position to serve as the axial imaging plane for the dynamic cine DENSE acquisition, which was defined to be perpendicular to the humerus and to include the biceps, brachialis and triceps with clearly-visualized boundaries (Fig. 2B). The axial images were then used to specify an oblique sagittal plane, which was defined to bisect the long head of the biceps brachii muscle and was oriented such that the superior-inferior direction of the image was parallel with the long axis of the distal aponeurosis (Fig. 2A). The imaging parameters for the static images included: field of view = 22 × 22 cm2, image matrix = 192 × 144, and slice thickness = 7 mm.

Fig. 2.

Representative static sagittal and axial images. A: A static image of the arm in the oblique-sagittal imaging plane with the elbow fully extended. The parallel lines show the position and orientation of the static axial imaging plane. B: Graphic prescription of the oblique-sagittal static imaging plane (the parallel lines), which was also used as the cine DENSE MR imaging plane, on a static axial image of the arm. The imaging plane was aligned with the longitudinal axis of the biceps (and therefore the muscle fascicle direction).

A segmented echo planar cine DENSE sequence that has previously been described for cardiac imaging (Kim et al., 2004; Spottiswoode et al., 2007) was used to acquire displacement encoded dynamic images of the upper arm during elbow flexion. Previous phantom studies have shown that displacement measurements acquired using this technique are accurate to within 0.1 pixels (Spottiswoode et al., 2007). The commencement of elbow flexion triggered the application of displacement-encoding pulses followed by multiphase RF excitation pulses and acquisition of a segment of k-space (Fig. 3). This process was repeated for a series of successive elbow flexions until all of k-space was filled for all dynamic phases. Three multiphase data sets were acquired, one for displacement encoding in each orthogonal direction. Phase reference images without displacement encoding were also acquired. The imaging parameters included: Field of view = 24 × 15 cm2, slice thickness = 8 mm, flip angle = 15°, TR = 10 ms, TE = 4.8 ms, echo train length = 3, number of phase encoding lines per motion phase per elbow flexion repetition = 9, temporal resolution = 30 ms, motion phases = 50, and displacement encoding frequency ke = 0.05 cycles/mm. The k-space matrix was 128 × 72, and then zero-padded to 128 × 80. Slice following (Fischer et al., 1994; Stuber et al., 1999) was used to obtain true through-plane motion for the axial view. Slice following is a method where an initial slice of muscle is tagged differently, using complimentary positive and negative tagging patterns, in two successive acquisitions. Immediately after tagging, image data are acquired from a relatively large volume containing the tagged slice. By subtracting the second acquired volume from the first, only the initially tagged signal is non-zero and contributes to the image signal intensity. Using this approach, the initially tagged slice is “followed” as it moves and deforms in three dimensions. Twenty-four repeated motion cycles were performed for each of the three orthogonal encoding directions and the phase reference images. Two additional repetitions were employed to eliminate artifacts resulting from imaging during the approach to steady state. Both oblique sagittal and axial cine DENSE data sets were obtained.

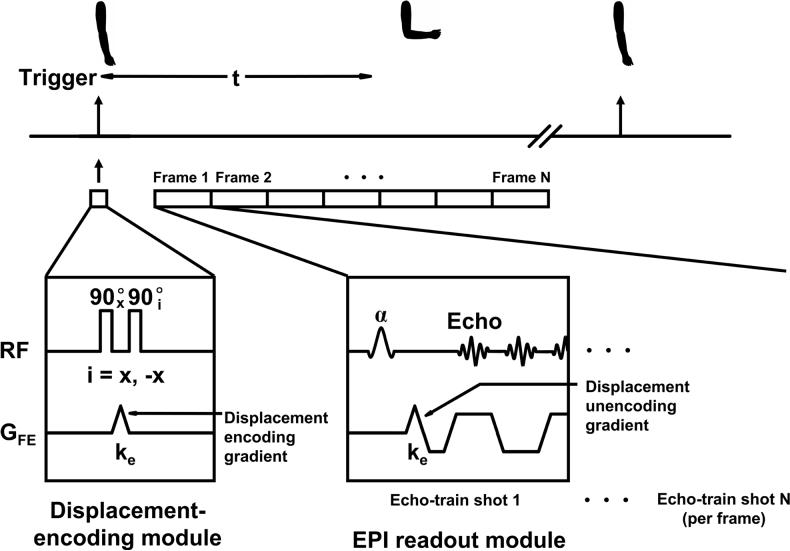

Fig. 3.

Pulse sequence timing diagram for cine DENSE MR imaging. The displacement-encoding module is played out immediately following a trigger with the onset of the elbow flexion. A segmented EPI sequence, modified to include DENSE encoding gradients, is used to sample the displacement-encoded longitudinal magnetization at multiple time frames. In practice, to minimize the echo time, the displacement-unencoding gradient was combined with spatial encoding gradients. In addition a flyback k-space trajectory was used to reduce ghosting (Kim et al., 2003). In this diagram, the displacement-encoding direction is applied in the frequency-encoding direction; however, more generally, displacement encoding can be applied in any direction.

2.3. Image Reconstruction and Data Analysis

Reconstruction of phase-corrected phase contrast DENSE images was performed online, and subsequent displacement and strain analysis of these data were performed offline using MATLAB (The Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA, United States) as described previously (Kim et al., 2004; Spottiswoode et al., 2007). Images with displacement encoding in orthogonal directions were registered using cross-correlation of the magnitude-reconstructed images of the entire arm. The boundary of the biceps brachii muscle was manually segmented. A spatiotemporal (two spatial dimensions and time) phase-unwrapping algorithm (Spottiswoode et al., 2007) was applied to the pixels within the boundary of the muscle, and the pixel phase was then directly converted to displacement relative to the time when the displacement encoding was initiated (Kim et al., 2004). For the axial view, the 3D displacement of each pixel was computed by means of vector addition of the three orthogonal one-dimensionally displacement-encoded data sets. For the sagittal view, the 2D displacement of each pixel was determined by means of vector addition of the two in-plane orthogonal one-dimensionally displacement-encoded data sets. The pixel-wise displacement trajectories were then obtained using vector-interpolation tissue tracking and Fourier-basis-function temporal fitting (Spottiswoode et al., 2007). The resulting multi-phase displacement maps depict intramuscular motion relative to the onset of the elbow flexion with a temporal resolution of 30 ms and a spatial resolution of approximately 1.9 × 1.9 mm2.

In order to compare our results with previous cine-PC results in the biceps brachii (Pappas et al., 2002), we calculated one-dimensional linear strains El along the centerline and anterior regions of the muscle. The distance between neighboring pixels within each region in the extended frame (De) and flexed frame (Df) were determined, and the strain was calculated as: (Df – De)/De. To remove the effects of variability in the achievable range of motion between volunteers, the strain was then normalized by the average value across the centerline of the biceps muscle. The normalized strains were expressed as a function of distance from the distal biceps tendon, normalized by the biceps muscle length, LM. For each subject, the normalized strain values were interpolated to increments of 2.5% of LM using cubic splines. Descriptive statistics are reported as means ± SDs.

To analyze the two-dimensional strain fields, the Lagrangian finite strain tensor E was calculated using the deformation gradient tensor (Mase and Mase, 1999). After diagonalization of E, the directions of the first and second principal strains and the corresponding eigenvalues, E1 and E2, were found, where the negative and positive eigenvalues were assigned to the first and second principal strains, respectively. The first and the second principal strains were calculated for small regions of interest (2 pixels in length × 1−4 pixels in width) along the anterior boundary and the centerline of the biceps brachii at maximum elbow flexion. Again, to remove the effects of variability in the achievable range of motion between volunteers, the mean strain was then normalized by the average value across the centerline of the biceps muscle. The normalized mean strains were expressed as a function of distance from the distal biceps tendon, normalized by the biceps muscle length LM. For each subject, the normalized mean strain values were interpolated to increments of 2.5% of LM using cubic splines. The directions of the first and second principal strains were expressed as the angle between the strain vector and the longitudinal axis of the biceps brachii.

3. Results

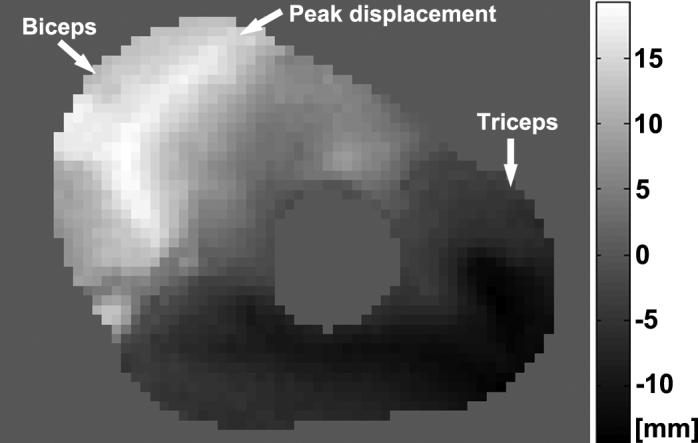

The phase-reconstructed DENSE images (e.g., Figs. 4 and 5) demonstrate that the displacement measurements are consistent with the muscles' actions – the antagonistic muscles (biceps brachii and triceps brachii) move in opposite directions during the elbow flexion. The corresponding displacement maps of three motion phases from the elbow extension to the elbow flexion show the extent of the motion recorded by the scans, and illustrate that the peak superior displacement occurs along the centerline of the biceps muscle (Fig. 6).

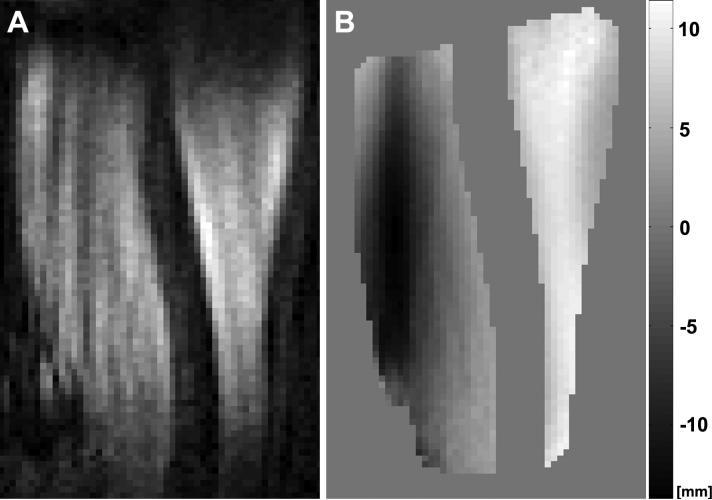

Fig. 4.

Example magnitude and phase images of cine DENSE MR imaging of the arm in the sagittal view at maximal elbow flexion. A: In the magnitude image muscle appears gray and bone appears black. B: The corresponding phase image after manually contouring the biceps and triceps muscles and phase-unwrapping. The displacement was encoded in the vertical direction, which is linearly proportional to the unwrapped phase. The gray scale indicates the proportional motion with respect to the phase values. The opposite signs of the biceps and the triceps muscles in the phase map clearly show the muscles working in opposite directions.

Fig. 5.

Example cine DENSE MR phase image of the arm in the axial view at maximal elbow flexion. The displacement was encoded in the through-plane direction. The gray scale indicates the proportional motion with respect to the phase values. The opposite signs of the biceps and the triceps muscles demonstrate that these antagonistic muscles are moving in opposite directions during the elbow flexion. Within the biceps muscle, the peak displacement generally follows the location the centerline of the muscle. The differential displacement within the muscle results in complex nonuniform strain distributions, as seen in the sagittal strain images shown in Fig. 8.

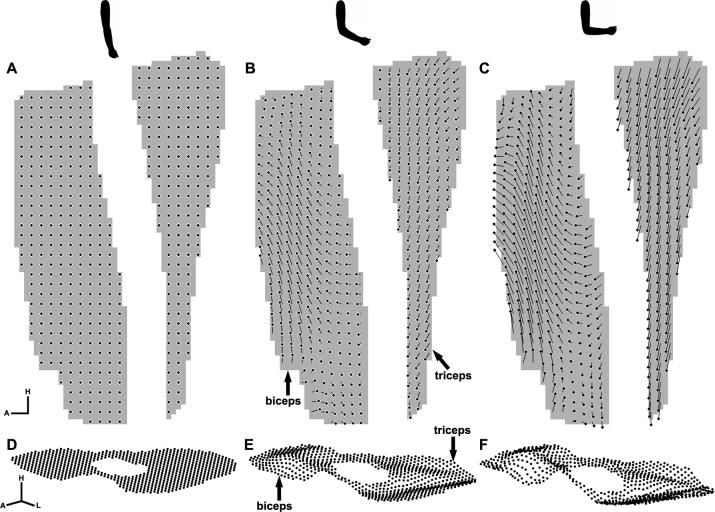

Fig. 6.

Example displacement maps corresponding to three motion phases at elbow extension(A, D), approaching elbow flexion (B, E), and elbow flexion (C, F). The upper row (A-C): 2D displacement map of the sagittal plane, where the head of the displacement trajectory indicates the 2D position of that element of muscle at this time point, and the tail indicates the position at the initial time point. The displacement map is spatially under-sampled for visualization purposes. The 2D axis represents the head and anterior directions. The lower row (D-F): 3D displacement map of the axial plane, where the dots indicate the 3D position of that element of muscle at this time point. The 3D axis represents the head, left and anterior directions. The displacement maps also demonstrate that the biceps and triceps muscles are moving in opposite directions during elbow flexion.

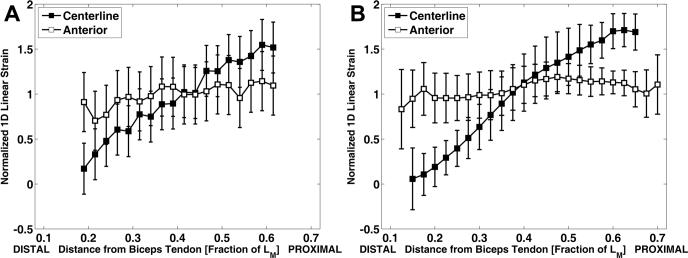

There was good agreement between the one-dimensional strain distributions extracted from the cine DENSE measurements in our study and previously published cine-PC measurements described by Pappas et al. (2002) in which one-dimensional shortening was estimated along both the centerline and anterior regions of the biceps on a different set of 12 volunteers. Our results showed uniform shortening along the anterior region of the muscle with an average normalized value of 0.99 and nonuniform shortening along the centerline region with a range of normalized values from 0.17 to 1.55 (Fig. 7A). Similarly, the previously published cine-PC results (described by Pappas et al. (2002) and shown in Fig. 7B) also showed uniform shortening along the anterior muscle fascicles (average normalized value was 1.06) and nonuniform shortening along the centerline fascicles (normalized values ranged from 0.06 to 1.71).

Fig. 7.

Comparison of the normalized one-dimensional linear strain El in the biceps brachii direction by cine DENSE MR imaging and cine-PC MR imaging published by Pappas et al. (2002). The strain is normalized by the mean value across the centerline of the biceps muscle, and is then plotted as a function of distance from the distal tendon, normalized by LM, the length of the biceps brachii long head muscle belly. A: Cine DENSE MR imaging results. Data were acquired from 6 normal volunteers. B: Cine PC MR imaging results. Data were from 12 normal volunteers.

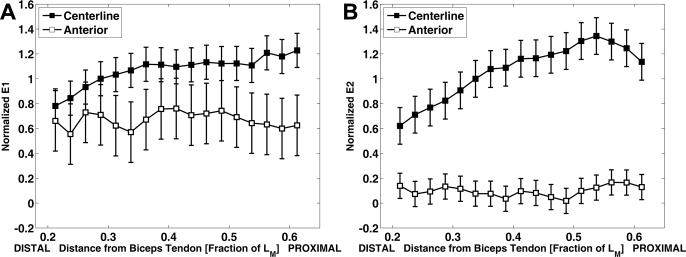

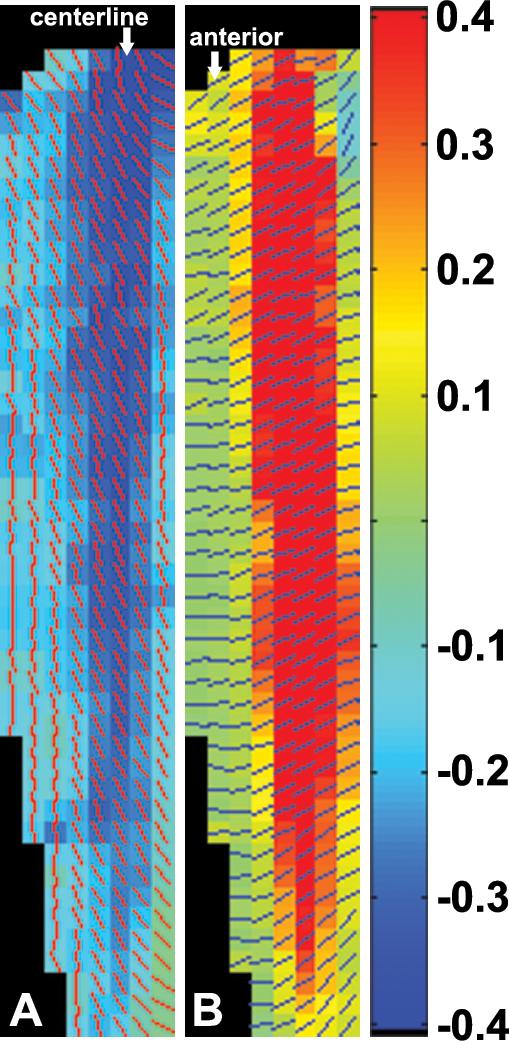

The Lagrangian strain maps (e.g., Fig. 8), strain profiles (Fig. 9), and strain values measured by cine DENSE (Table 1) illustrate the two-dimensional complexity of the tissue behavior. The first and second principal strains were both uniform along the anterior region, and first and second principal strains were nonuniform along the centerline region. The relative values of the first and second principal strains also differed between the anterior and centerline regions (Table 1). Along the anterior region, the first principal strains were larger in magnitude than the second principal strains. By contrast, along the centerline region, the second principal strains were larger in magnitude than the first principal strains. These results indicate that, not only is the shortening nonuniform throughout the muscle, but the nature of the deformation is also substantially different between the centerline and anterior regions.

Fig. 8.

Example of the first principal strain E1 (A) and the second principal strain E2 (B) with the bars indicating the direction of strain vectors. Negative strain values represent local tissue element shortening during elbow flexion; and positive strain values represent local tissue element stretching. The centerline and the anterior fascicles can be easily identified in the strain maps.

Fig. 9.

Normalized E1 (A) and E2 (B) along the centerline and the anterior boundary of the biceps brachii at maximal elbow flexion acquired from 6 normal volunteers. All strains are normalized by the average E1 value along the centerline of the muscle. The normalized strains are plotted as a function of the normalized distance along the biceps muscle. First principal strains (E1) correspond to shortening, and second principal strains (E2) correspond to lengthening. Along the centerline, both first and second principal strains are uniform; however, the second principal strains are larger in magnitude than the first principal strains. By contrast, along the anterior region, both first and second principal strains are uniform; however, the second principal strains are smaller in magnitude than the first principal strains.

Table 1.

Unnormalized and normalized strain values summarized from six volunteers.*

| Average E1 | Average E2 | Max E1 | Max E2 | Min E1 | Min E2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unnormalized | Centerline | −0.23 ± 0.07 | 0.34 ± 0.14 | −0.30 ± 0.09 | 0.54 ± 0.22 | −0.07 ± 0.06 | 0.10 ± 0.05 |

| Anterior | −0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.03 ± 0.04 | −0.18 ± 0.07 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | −0.09 ± 0.06 | −0.02 ± 0.06 | |

| Normalized | Centerline | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 1.49 ± 0.42 | 1.35 ± 0.16 | 2.36 ± 0.74 | 0.27 ± 0.17 | 0.45 ± 0.14 |

| Anterior | 0.66 ± 0.25 | 0.14 ± 0.20 | 0.85 ± 0.30 | 0.44 ± 0.13 | 0.40 ± 0.23 | −0.06 ± 0.30 |

The values are reported as means ± SDs.

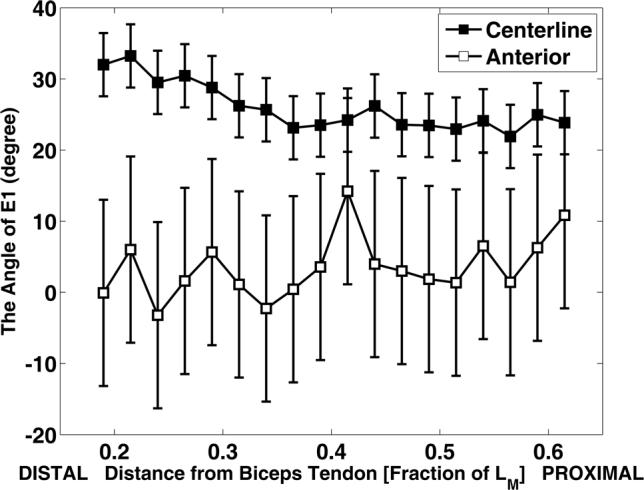

The principal strain directions were also nonuniform throughout the muscle (Fig. 10). In the proximal half of the centerline region, the first principal strain vectors were oriented at an angle of approximately 25 degrees relative to the centerline. However, a previous ultrasound study (Asakawa et al., 2002b) showed that fascicles in this region are oriented directly along the centerline of the muscle. Our results suggest that the principal direction of shortening varies throughout the muscle and is not necessarily aligned with the muscle fascicle direction.

Fig. 10.

Direction angles of E1 as a function of the normalized distance. The direction is expressed as the angle between the E1 strain vector and the longitudinal axis of the biceps brachii. Data were acquired from 6 normal volunteers.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to apply cine DENSE imaging to characterize strain fields in the long head of the biceps brachii muscle during low-load elbow flexion. The one-dimensional linear strain distributions extracted from the cine DENSE measurements were consistent with previous cine phase-contrast measurements in the same muscle (Pappas et al., 2002). The major finding of the present study is that two-dimensional strains were nonuniform throughout the biceps brachii muscle during low-load elbow flexion. The directions, magnitudes, and relative magnitudes of the first and the second principal Lagrangian strains were nonuniform throughout the muscle. These results describe the in vivo mechanics of skeletal muscle to a level of detail that has not been previously possible and can be used to validate and improve computational models of skeletal muscle (Blemker and Delp, 2005; Fernandez et al., 2005; Yucesoy et al., 2002).

The two-dimensional strains determined in this study illustrate the fact that skeletal muscle contraction involves complex multi-dimensional deformation. The first principal strain direction results imply that the principal direction of muscle tissue shortening is not necessarily aligned with the muscle fiber direction and that contraction involves substantial shearing between fibers. Previous theoretical and computational studies have suggested that muscle tissue undergoes substantial shearing between fibers (Blemker et al., 2005; Huijing, 1999). Characterization of the shearing behavior between fibers is important because it influences the potential for fibers to transmit force laterally via intramuscular connective tissue (Huijing, 1999; Purslow, 2002). Future studies that compare principal strain directions extracted from cine DENSE imaging with detailed measurements of fiber directions (from ultrasound or diffusion tensor imaging) will allow for a more in-depth exploration of the precise nature of shearing behavior between fibers.

Other investigators have characterized skeletal muscle tissue motion using cine phase-contrast (cine-PC) imaging (Asakawa et al., 2002a; Finni et al., 2003; Pappas et al., 2002; Zhou and Novotny, 2007). Cine-PC imaging encodes pixel velocities into the phase of the image (Pelc et al., 1991), and displacements and strains are determined by integrating velocities through space and time. Two of the major limitations of the cine-PC imaging approach are that (i) in order to translate velocity into displacement, the motion is assumed to be linear, and (ii) the strain estimates are sensitive to errors in the calculated displacements that accumulate over time. To account for these errors, velocity measures are generally averaged over several pixels (Zhu et al., 1996), which limits the ability to extract detailed two-dimensional strain fields from cine-PC based estimates of displacements. The strains extracted from cine DENSE images are not based on a linear motion assumption and are not sensitive to error accumulation since the displacements, rather than velocities, are directly encoded into the phase of the image.

Other methods for directly measuring displacement include myocardial tagging (Zerhouni et al., 1988; Axel and Dougherty, 1989), and harmonic phase analysis (HARP) (Osman et al., 1999; Osman et al., 2000; Osman and Prince, 2000). One disadvantage of tagging is the reduced spatial resolution of strain relative to the image spatial resolution. Although it may be interpolated to any desired spatial resolution, the fundamental spatial resolution of strain is nominally determined by the distance between the tag lines, which is typically several pixels. The second disadvantage of tagging is that tag detection typically requires substantial time-consuming manual intervention. HARP obviates tag detection, but the spatial resolution of the resultant strain is not improved over tagging. In contrast to tagging and HARP, cine DENSE provides pixel-wise displacement data and the ability to automatically and quickly extract pixel-wise strain fields.

Several future improvements in the technique will further advance the utility of cine DENSE imaging for studying skeletal muscle. First, the reliability of the displacement measurements is currently dependent on the subjects' ability to perform repeatable flexion-extension motion. To account for this, we triggered the imaging sequence with the beginning of the motion cycle to minimize effects of non-repeated motion. In the future, higher field strengths, parallel imaging, and artifact reduction strategies that require fewer acquisitions (Zhong et al., 2006), should reduce the required number of repeated motion cycles. Second, not all of our subjects could achieve the same range of motion within the constraints of the MRI bore, which added some variability in the magnitudes of the displacement and strain measurements. To account for this difference, we normalized the strain results to the mean strain for each subject, since our focus was characterizing how strains were distributed throughout the muscle. Usage of large or open-bore systems will allow for a larger range of motion and therefore eliminate the effects of variability in range of motion. Third, the need for several repeated motions limited us to a low load condition in this experiment. Though, interestingly, even in the low load of this experiment, we still observed relatively complex nonuniform strain fields. Implementation of a faster cine DENSE sequence will allow for analyses of mechanics at higher and even maximum loading conditions. Finally, we were limited by imaging in one plane, and therefore could not analyze the full three-dimensional motion of the muscle. To ensure that our measurements were not affected by this limitation, we carefully chose the imaging plane to minimize the through-plane motion. Future developments that allow for three-dimensional measurements of displacements and strains throughout large volumes will further enhance the utility of DENSE for characterizing skeletal muscle motion.

Cine DENSE imaging has the potential to provide the data needed to improve our understanding of muscle contraction mechanics and rigorously evaluate predictions made by muscle models. Muscle pathologies are often manifested by alterations in fibers (Tardieu et al., 1982), connective tissue (Lieber et al., 2003), and passive structures (Shortland et al., 2002). Analyzing skeletal muscle mechanics using cine DENSE imaging in persons with muscle pathology will lead to an advanced understanding of how these alterations affect muscle behavior and function. These results, combined with computational models of muscle, may lead to more accurate and individualized muscle models that can capture effects of pathology and can be used to gain new insights into the causes of movement abnormalities and to simulate novel treatment strategies.

Acknowledgements

This study was financially supported in part by NIH grants R01 AR 056201 and RO1 EB 001763, the Funds for Excellence in Science and Technology at the University of Virginia, and Siemens Medical Solutions. These sponsors had no involvement in the specific study design and/or analysis. We also gratefully acknowledge George Pappas for sharing previous cine-PC imaging results.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aletras AH, Balaban RS, Wen H. High-resolution strain analysis of the human heart with fast-DENSE. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1999a;140:41–57. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aletras AH, Ding S, Balaban RS, Wen H. DENSE: displacement encoding with stimulated echoes in cardiac functional MRI. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1999b;137:247–252. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aletras AH, Wen H. Mixed echo train acquisition displacement encoding with stimulated echoes: an optimized DENSE method for in vivo functional imaging of the human heart. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2001;46:523–534. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa DS, Blemker SS, Gold GE, Delp SL. In vivo motion of the rectus femoris muscle after tendon transfer surgery. Journal of Biomechanics. 2002a;35:1029–1037. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa DS, Pappas GP, Delp SL, Drace JE. Aponeurosis length and fascicle insertion angles of the biceps brachii. Journal of Mechanics in Medicine and Biology. 2002b;2:449–455. [Google Scholar]

- Axel L, Dougherty L. MR imaging of motion with spatial modulation of magnetization. Radiology. 1989;171:841–845. doi: 10.1148/radiology.171.3.2717762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blemker SS, Delp SL. Three-dimensional representation of complex muscle architectures and geometries. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2005;33:661–673. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-1433-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blemker SS, Pinsky PM, Delp SL. A 3D model of muscle reveals the causes of nonuniform strains in the biceps brachii. Journal of Biomechanics. 2005;38:657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delp SL, Loan JP, Hoy MG, Zajac FE, Topp EL, Rosen JM. An interactive graphics-based model of the lower extremity to study orthopaedic surgical procedures. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 1990;37:757–767. doi: 10.1109/10.102791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez JW, Buist ML, Nickerson DP, Hunter PJ. Modelling the passive and nerve activated response of the rectus femoris muscle to a flexion loading: a finite element framework. Medical Engineering & Physics. 2005;27:862–870. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finni T, Hodgson JA, Lai AM, Edgerton VR, Sinha S. Mapping of movement in the isometrically contracting human soleus muscle reveals details of its structural and functional complexity. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003;95:2128–33. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00596.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer SE, McKinnon GC, Scheidegger MB, Prins W, Meier D, Boesiger P. True myocardial motion tracking. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1994;31:401–413. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910310409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson WD, Yang Z, French BA, Epstein FH. Complementary displacement-encoded MRI for contrast-enhanced infarct detection and quantification of myocardial function in mice. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2004;51:744–752. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AM, Huxley AF, Julian FJ. The variation in isometric tension with sarcomere length in vertebrate muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology. 1966;184:170–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp007909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijing PA. Muscle as a collagen fiber reinforced composite: a review of force transmission in muscle and whole limb. Journal of Biomechanics. 1999;32:329–345. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00186-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Bove CM, Kramer CM, Epstein FH. Importance of k-space trajectory in echo-planar myocardial tagging at rest and during dobutamine stress. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2003;50:813–820. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Gilson WD, Kramer CM, Epstein FH. Myocardial tissue tracking with two-dimensional cine displacement-encoded MR imaging: development and initial evaluation. Radiology. 2004;230:862–871. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303021213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber RL, Runesson E, Einarsson F, Friden J. Inferior mechanical properties of spastic muscle bundles due to hypertrophic but compromised extracellular matrix material. Muscle Nerve. 2003;28:464–471. doi: 10.1002/mus.10446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mase GT, Mase GE. Continuum Mechanics for Engineers. CRC Press,; Boca Raton, London, New York, Washington D.C: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Osman NF, Kerwin WS, McVeigh ER, Prince JL. Cardiac motion tracking using CINE harmonic phase (HARP) magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic Resonance Medicine. 1999;42:1048–1060. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199912)42:6<1048::aid-mrm9>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman NF, McVeigh ER, Prince JL. Imaging heart motion using harmonic phase MRI. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2000;19:186–202. doi: 10.1109/42.845177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman NF, Prince JL. Visualizing myocardial function using HARP MRI. Physics in Medicine & Biology. 2000;45:1665–1682. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/45/6/318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas GP, Asakawa DS, Delp SL, Zajac FE, Drace JE. Nonuniform shortening in the biceps brachii during elbow flexion. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2002;92:2381–2389. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00843.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelc NJ, Herfkens RJ, Shimakawa A, Enzmann DR. Phase contrast cine magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic Resonance Quarterly. 1991;7:229–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purslow PP. The structure and functional significance of variations in the connective tissue within muscle. Comparative Biochemistry & Physiology. 2002;133(4):947–966. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortland AP, Harris CA, Gough M, Robinson RO. Architecture of the medial gastrocnemius in children with spastic diplegia. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2002;44:158–163. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201001864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spottiswoode BS, Zhong X, Hess AT, Kramer CM, Meintjes EM, Mayosi BM, Epstein FH. Tracking myocardial motion from cine DENSE images using spatiotemporal phase unwrapping and temporal fitting. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2007;26:15–30. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2006.884215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber M, Spiegel MA, Fischer SE, Scheidegger MB, Danias PG, Pedersen EM, Boesiger P. Single breath-hold slice-followed CSPAMM myocardial tagging. Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine. 1999;9:85–91. doi: 10.1007/BF02634597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardieu C, Huet d.l.T.E., Bret MD, Tardieu G. Muscle hypoextensibility in children with cerebral palsy: I. Clinical and experimental observations. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1982;63:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yucesoy CA, Koopman BHFJ, Huijing PA, Grootenboer HJ. Three-dimensional finite element modeling of skeletal muscle using a two-domain approach: linked fiber-matrix mesh model. Journal of Biomechanics. 2002;35:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajac FE. Muscle and tendon: properties, models, scaling, and application to biomechanics and motor control. Critical Reviews in Biomedical Engineering. 1989;17:359–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerhouni EA, Parish DM, Rogers WJ, Yang A, Shapiro EP. Human heart: tagging with MR imaging--a method for noninvasive assessment of myocardial motion. Radiology. 1988;169:59–63. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.1.3420283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X, Spottiswoode BS, Cowart EA, Gilson WD, Epstein FH. Selective suppression of artifact-generating echoes in cine DENSE using through-plane dephasing. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2006;56:1126–1131. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Novotny JE. Cine phase contrast MRI to measure continuum Lagrangian finite strain fields in contracting skeletal muscle. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2007;25:175–184. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Drangova M, Pelc N. Fourier tracking of myocardial motion using cine-PC data. Magnetic Resonance Medicine. 1996;35:471–480. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]