Abstract

The KdpFABC complex (Kdp) functions as a K+ pump in Escherichia coli and is a member of the family of P-type ATPases. Unlike other family members, Kdp has a unique oligomeric composition and is notable for segregating K+ transport and ATP hydrolysis onto separate subunits (KdpA and KdpB, respectively). We have produced two-dimensional crystals of the KdpFABC complex within reconstituted lipid bilayers and determined its three-dimensional structure from negatively stained samples using a combination of electron tomography and real-space averaging. The resulting map is at a resolution of 2.4 nm and reveals a dimer of Kdp molecules as the asymmetric unit; however, only the cytoplasmic domains are visible due to the lack of stain penetration within the lipid bilayer. The sizes of these cytoplasmic domains are consistent with Kdp and, using a pseudoatomic model, we have described the subunit interactions that stabilize the Kdp dimer within the larger crystallographic array. These results illustrate the utility of electron tomography in structure determination of ordered assemblies, especially when disorder is severe enough to hamper conventional crystallographic analysis.

Keywords: Kdp, P-type ATPase, ion transport, electron tomography, real-space average, homology model

1. Introduction

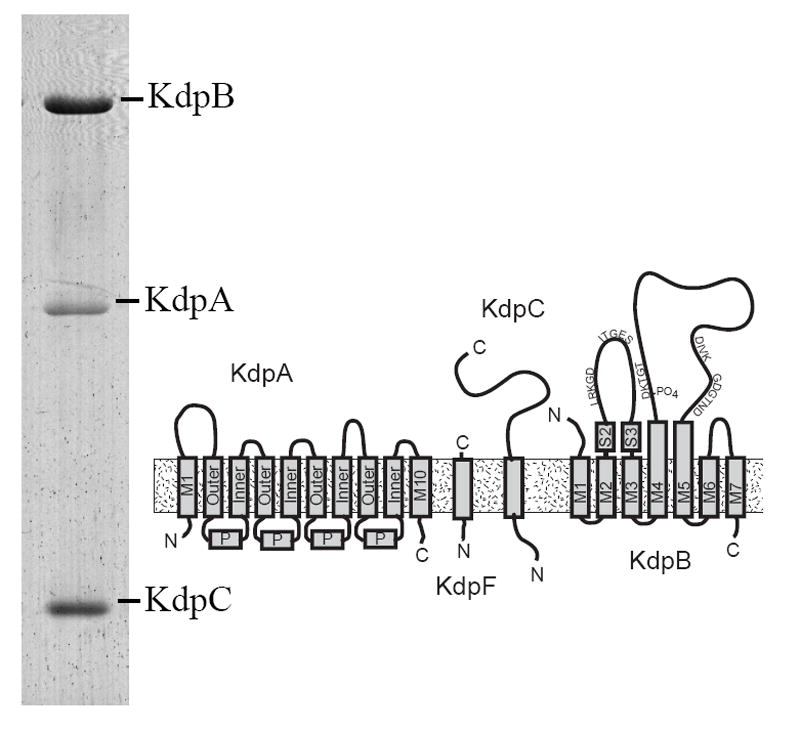

The KdpFABC complex (Kdp) is an ATP-dependent K+ pump and a member of the type IA subfamily of P-type ATPases. In E. coli, Kdp functions as an inducible K+ uptake system to regulate turgor pressure when other K+ transport systems fail to maintain homeostasis (Epstein, 2003, Epstein and Davies, 1970). The oligomeric organization of Kdp is unique amongst P-type ATPases, which are generally characterized by a single polypeptide responsible for both ATP-hydrolysis and transport. In the case of Kdp, four membrane-bound subunits (KdpA, KdpB, KdpC and KdpF, Fig. 1) are encoded on a single kdp operon together with regulatory response elements KdpD and KdpE (Rhoads et al., 1978). KdpA has been shown by mutagenesis to be responsible for K+ transport (Bertrand et al., 2004, Buurman et al., 1995, Schrader et al., 2000, van der Laan et al., 2002) and has been predicted to have 10 transmembrane helices with a structure analogous to KcsA, the bacterial homologue of a K+ channel (Buurman et al., 1995, Durell et al., 2000). KdpB functions as the catalytic subunit that couples K+ transport by KdpA to ATP hydrolysis within KdpB cytoplasmic domains. KdpB has the characteristic sequence homologies and domain organization of P-type ATPases (Hesse et al., 1984), including seven core transmembrane helices and three cytoplasmic domains that are organized around the site of auto-phosphorylation. KdpC has a single transmembrane helix and seems to mediate the interaction between KdpB and KdpA (Gassel and Altendorf, 2001, Gassel et al., 1998). KdpC is unique to Type IA P-type ATPases and its presence may reflect the necessities of coupling ion transport and ATP hydrolysis when segregated onto separate subunits. The KdpF subunit appears to be optional for the membrane-bound complex, but stabilizes the enzyme in the detergent-solubilized state (Gassel et al., 1999). The physical assembly of these subunits and the structural interactions that lead to K+ transport remain open questions.

Figure 1. Architecture of the Kdp-ATPase.

A Coomassie-stained SDS gel shows the preparation that was used for crystallization. Three of the four subunits are clearly resolved, whereas KdpF was too small (6.2 kD) to be retained by this gel system. KdpA is largely hydrophobic and is therefore more weakly stained than the other subunits. The diagram illustrates the topology of the four subunits composing the Kdp complex. KdpA consists of four repeats of the KcsA motif, labeled as “Outer”, “P” and “Inner”, with an additional helix at both the N- and C-termini. KdpB has seven transmembrane helices and sequence motifs conserved amongst all P-type ATPases along the cytoplasmic domains (indicated by the single letter amino acid code). KdpC and KdpF are smaller subunits with a single transmembrane helix.

In the current work, we have grown tubular crystals of Kdp from E. coli. As a result of the negative stain used to preserve the crystals for electron microscopy, the tubular crystals were partially flattened, thus distorting the underlying helical symmetry but having sufficient residual curvature to prevent a conventional 2D crystallographic approach. As an alternative, we used electron tomography and real-space averaging of unit cells to determine a 3D structure. The resulting structure illustrates the utility of applying electron tomography to crystalline assemblies, especially when their morphologies prevent the use of conventional crystallographic reconstruction methods.

2. Methods

2.1. Preparation of tubular crystals and EM grids

The Kdp complex was purified from E. coli membranes according to the procedure described by Fendler et al. (1996) at a protein concentration of 0.8-1 mg/ml in a buffer containing 15 mM HEPES-Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.2% decylmaltoside. Reconstitution of Kdp was accomplished by mixing this protein with a 1 mg/ml solution of phospholipids (80% dioleoylphosphatidylcholine, 20% dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine) in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2% octylethyleneglycol mono-n-docecylether (C12E8) with a protein:lipid weight ratio of 2:1. SM2 Biobeads (Biorad) were added incrementally over a 4 hr period in order to achieve a final weight ratio of 16 g hydrated Biobeads per mg of detergent (decylmaltoside+C12E8). Initial Biobead additions were smaller (weight ratio of 1g/mg every 30 min) followed by 2 larger additions of 4g/mg and 8g/mg during the 3rd and 4th hr. The resulting proteoliposomes were purified on a sucrose density gradient, collected by centrifugation at 200,000 g for 90 min and, after washing, were finally resuspended in a crystallization buffer of 50 mM Tris-Cl pH7.5, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.5 mM decavanadate. After incubation at 4°C for several days, samples were prepared for electron microscopy by negative staining with 2% uranyl acetate on a solid carbon support.

2.2. Electron tomography

Individual electron micrographs were collected with a 4k×4k CCD camera (model F415 TVIPS) at nominal magnifications of either 43,000× or 50,000× using the serialEM program (Mastronarde, 2005) running on a Tecnai F20 electron microscope (FEI Corp). The specimen was systematically tilted from -70° to +70° with increments chosen according to the cosine rule using a high-tilt tomography holder (model 2020, Fischione Instruments). A complete tomographic data set consisted of ~100 images recorded with an electron dose of ~2e-/A2 each, and a defocus of ~1 μm, though one tilt series was recorded with ~6 μm defocus. Image pixels were binned 2-fold to produce an effective pixel size of 0.7 nm for 43,000× images and 0.6 nm for 50,000× images.

2.3. Image analysis

Tomographic image reconstruction was performed using marker-free alignment as implemented in the software package by Winkler and Taylor (Winkler and Taylor, 2006). This is an iterative alignment, which we judged to have converged when image shifts relative to the last refinement round were less than 0.5 pixel (0.35 or 0.3 nm depending on the magnification) and residual deviations were less than 1%. No defocus correction was applied to the data recorded at ~1 μm defocus, since the first zero of the contrast transfer function was at 1.6 nm resolution and therefore fell beyond the ultimate resolution of the reconstruction (2.4 nm). For the tilt series with 6 μm defocus, CTF correction was applied as follows. Power spectra were averaged incoherently from subareas of 512×512 pixels taken along the tilt axis and were used to estimate the precise defocus with PLTCTFX (Tani et al., 1996). A Weiner filter was then applied using SPIDER (Frank et al., 1996) assuming a signal-to-noise ratio of 5.0 to the individual projection images; these corrected images were then used to calculate the tomographic reconstruction for each Kdp crystal by 3D backprojection. Although the signal-to-noise ratio of individual tomograms is likely to be lower, the value of 5 was chosen to reflect the signal enhancement achieved by the real-space averaging described below.

Following the tomographic reconstruction of each individual crystal, we used real-space averaging of unit cells to optimize the resolution as previously described by Liu et al. (2006). Briefly, cross-correlation was used to locate the positions of unit cells. The reference image for this cross-correlation was created by first applying a Fourier filter to the tomogram, based on the 2D lattice parameters calculated from a single slice through the middle of the tomogram. A 3D subvolume containing ~12 unit cells was then extracted from this filtered tomogram and used for the cross-correlation. A series of 3D subvolumes were then extracted from the original tomogram centered on locations of the cross-correlation peaks. These subvolumes were aligned relative to an initial reference taken either from the Fourier-filtered tomogram or from a simple average of the subvolumes, which were approximately aligned due to the underlying crystallographic symmetry. This process was iterated using the new average as a reference for cross-correlation, extraction, alignment and averaging; convergence was judged by the Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) calculated by dividing the data set in half. Thus, each tomogram produced an independent, averaged 3D structure. The missing wedge of Fourier data was not considered during this analysis, because the motifs extracted from a single crystal which all had a very similar orientation and alignments were therefore unlikely to suffer from the artifacts that arise when missing wedges are misaligned. The FSC was used to judge the similarity of these structures and as a criterion for further averaging to produce the final structure. For averaging structures derived from different magnifications, a scale factor was chosen to maximize this FSC. It is noteworthy that a Gaussian mask encompassing several unit cells was always applied to the volume prior to alignment and calculation of the FSC. For the FSC of the final, averaged map, the individual subvolumes from all the tomographic reconstructions were pooled; this pool was then arbitrarily divided into two groups, which were averaged and these averages were used for the final FSC.

2.4. Pseudo-atomic model for Kdp

A model for KdpB was based on the X-ray crystallographic model of the E2 state of Ca2+-ATPase (PDB ID 2C8L, Jensen et al., 2006) using the sequence alignments of Green (1989) to identify and remove several regions not present in Kdp, which has only 682 residues compared with 1001 for SERCA. First, the last three transmembrane helices of SERCA were truncated. Next, we substituted the published NMR structure for the N-domain of KdpB (Haupt et al., 2004) and removed a variable loop including helices 4 and 4’ in the P-domain (Toyoshima et al., 2000). Finally, two short α-helices were truncated from the N-terminus of KdpB due to a corresponding deletion of 25 residues in this highly variable region of P-type ATPases. This composite model was then docked into the EM density map together with the X-ray structure of KcsA (Doyle et al., 1998), acting as a surrogate for the KdpA subunit (Durell et al., 2000). This fitting was done manually using Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004). Any sort of automated fitting or statistical measure of the fit were hampered by the lack of contrast in the membrane region of the map.

2.5. Image processing software

Image conversion was done with EM2EM (van Heel et al., 1996) and/or EMAN (Ludtke et al., 1999); tomographic reconstruction and real-space averaging was done with software from Winkler and Taylor (2006). Images and reconstructions were visualized mainly with IMOD (Kremer et al., 1996), whereas the modeling and structure rendering was done with Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystallization

In order to investigate the structure of Kdp, we grew two-dimensional crystals from purified, detergent-solubilized Kdp (Fig. 1). For crystallization, we used Biobeads to remove the detergent in the presence of exogenous lipids and incubated the resulting proteoliposomes in a crystallization solution that stabilized the E2 enzymatic state (Moller et al., 2005). Solutions containing orthovanadate generally produced more numerous and better ordered crystals, though this inhibitor did not seem to be absolutely required for crystallization, suggesting that a phosphate analogue was not essential.

3.2. Structure determination by electron tomography

The resulting two-dimensional crystals took the form of cylindrical membrane tubes with Kdp arranged in a helical lattice within the membrane. In negative stain, the tubes with diameters >100 nm flattened on the carbon support film and therefore did not maintain their helical symmetry. As a result of this flattening, tubes were not suitable for the Fourier Bessel reconstruction (DeRosier and Moore, 1970). On the other hand, the flattened tubes retained a significant amount of curvature, meaning that conventional methods of two-dimensional crystallography (Unwin and Henderson, 1975) would also be problematic. As an alternative, we turned to electron tomography to generate a three-dimensional structure and made use of real-space averaging to optimize the resolution.

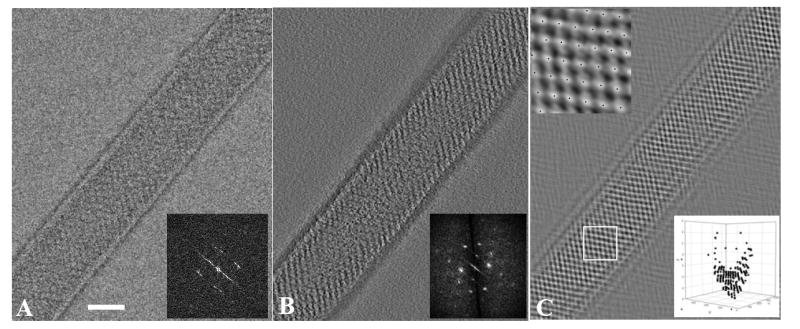

Fig. 2A shows a projection image of an untilted Kdp crystal recorded with a rather low dose of 2 electrons/Å2; the two-dimensional lattice can be detected, but the corresponding diffraction is blurred due to residual curvature. One would normally expect to see a second lattice coming from the other side of the tube, but these were generally faint, presumably due either to disordering of one surface or to an uneven accumulation of negative stain around the tube. Fig. 2B shows a 0.7-nm thick section from the tomogram in which the two-dimensional lattice has much higher contrast due to the combined signal from many images in the reconstruction and to the lack of superposition in this section. The molecules are arranged in rows and the diffraction produces discrete reflections. The average unit cell parameters of this lattice were measured to be a=100.5 Å (S.D. 1.90 Å), b=121.9 Å (S.D. 4.1 Å) and γ=116.6° (S.D. 4.1°). The lattice is absent in the middle of this section due to the curvature of the tube; indeed, several sections away the lattice is visible in the middle and obscured at the edges. By panning through the tomogram, it was apparent that the surface of the tube in contact with the carbon film was disordered and that the 2D lattice was most clearly visible 80-90 Å above this film. This observation suggests that the tube is fully embedded in stain, but that adsorption to the carbon film caused disordering of the lattice on the corresponding surface of the tube.

Figure 2. Images of two-dimensional crystals of Kdp.

(A) Projection image of negatively stained Kdp crystals taken from a tomographic data set corresponding to zero tilt. In order to avoid excessive beam damage, the dose for each image was limited to ~2 e-/Å2, accounting for the relatively noisy appearance of this image. The corresponding Fourier transform is shown in the inset, revealing a number of discrete reflections, which are blurred due to the residual curvature in the plane of the crystal. (B) A 0.7-nm thick slice from the 3D tomographic reconstruction near the surface of this Kdp tube. The corresponding Fourier transform is shown in the inset and reveals Fourier reflections to ~3 nm resolution. The lattice was used to construct a mask for the 3D Fourier transform, which in turn produced a filtered image for a cross-correlation reference. (C) 2D projection of the resulting cross-correlation map reveals the location of each unit cell across the crystal. Individual peaks are marked by black dots and are visible in the higher magnification image in the upper inset. The lower inset shows a 3D plot of unit cell positions from a region in the middle of this crystal; the viewing angle of this plot corresponds to the tube axis. Note that unit cells have a higher Z coordinate at the edges of the tube, illustrating the residual curvature.

3.3. Averaging of unit cells derived from the tomographic structure

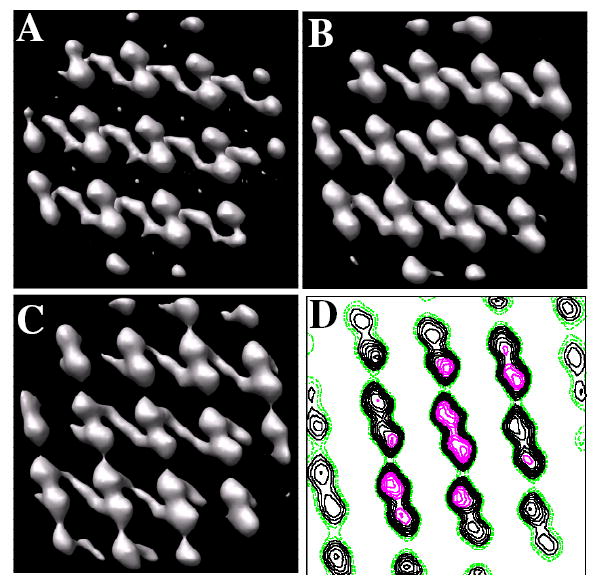

Although individual molecules are visible in the tomographic map and provide a 3D structure for Kdp, we employed real-space averaging of the unit cells composing the crystal in order to improve the resolution and fidelity of the reconstruction. For the first step, the locations of individual unit cells were identified by cross-correlation of a reference structure against the tomogram. The reference structure was generated by first applying a 3D Fourier filter to the tomogram and then extracting a motif from the center of the filtered tomogram. This filter included the crystallographic reflections seen in the inset to Fig 1B, but excluded the intervening noise. Thus, most of the unit cells in the tube produced high correlation with the reference. The corresponding locations of the unit cells are represented as black dots in the two-dimensional projection of the cross correlation map (Fig. 2C). These unit cells were actually localized in three dimensions as shown by the plot of unit cell locations in the lower inset of Fig. 2C. This plot illustrates the curvature of the tube, with unit cells having a 5-6 nm difference in their Z coordinate relative to unit cells in the middle of the tubes. At each of these locations, subvolumes were extracted and were aligned to a reference. The reference was derived from the average of all these subvolumes (Fig. 3A) which, initially, were roughly aligned due to the underlying crystallographic symmetry. This alignment was improved through several rounds of refinement and converged on the structure shown in Fig. 3B. We did not attempt to classify the motifs and perform multireference alignment, because they all came from a single, coherent two-dimensional lattice, which should preclude the conformational variability sometimes seen in isolated complexes.

Figure 3. Kdp motifs used for real-space averaging.

Based on the cross-correlation map in Fig. 2, 3D motifs were extracted from the tomographic map consisting of ~12 unit cells (42×42×28 nm3). (A) Initial reference for alignment of motifs from an individual tomogram was generated by simply averaging the motifs extracted according to their positions in the cross-correlation map. (B) Averaged motif from an individual tomogram after two rounds of alignment. (C) Averaged motif from the combination of six tomograms. The unit cell appears to consist of dimers, although no two-fold symmetry has been applied. Strong connections are apparent in the horizontal direction. Because these crystals have been negatively stained, the transmembrane region is not visible in these maps. Thus, connections between unit cells in the vertical direction, which are not visible in this map, most likely occur within the transmembrane region. (D) Contour plot of one 0.7-nm slice through the map. Stronger density is seen in the middle of the map due to the use of a Gaussian mask during alignment steps; slight differences in unit cell parameters for individual crystals lead to a blurring at the edges of the map and therefore a loss in contrast.

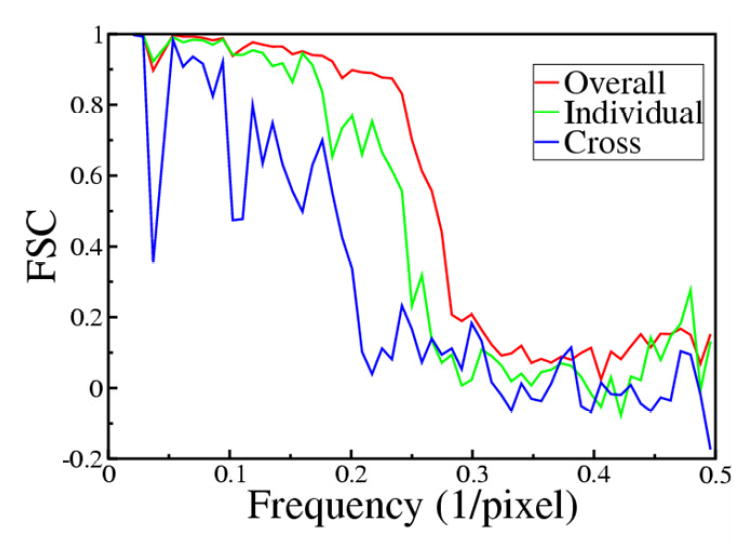

This refinement produced an averaged, 3D motif for each individual crystal and motifs from six crystals were then aligned and averaged to produce the final 3D structure. The FSC was used to document resolution and also to verify the similarity of reconstructions from individual crystals (Fig. 4 and Table I). For individual crystals, data was divided in half for the FSC calculation and the corresponding FSC suggested resolutions between 2.5 and 3.0 nm, based on a cutoff of 0.5. In general, data from individual crystals correlated better than data from two different crystals (Table I). This discrepancy likely reflects differences in stain distribution, flattening and/or overlap of the missing wedge that results from the single axis tilt geometry. Indeed, tomograms derived from two different crystals with a similar orientation on the same grid square (data sets 1 and 2 in Table I) produced FSC curves equivalent to those from each individual crystal. Despite all these differences, data from six independent crystals were averaged and the resulting FSC indicated an overall resolution of 2.4 nm (Fig. 4). Given the variety of orientations represented in these six crystals relative to the tomographic tilt axis, the averaged structure represents a relatively good coverage of Fourier space up to the maximum tilt angle of 70°. Figs. 3C and D show the global average from all six tomograms. This average appears blurred at the edges of the field, which reflects the procedures used for real-space averaging. In particular, a Gaussian mask was applied to all the motifs to focus on the molecules at the center of the field during alignment; slight differences in unit cell parameters, curvature, or magnification would place the peripheral molecules in somewhat different positions, producing the observed loss of definition in the map (see particularly Fig. 3D).

Figure 4. Resolution of the reconstructions.

We used the Fourier Shell Coefficient (FSC) to judge the resolution of maps. The blue line represents the FSC between two different reconstructions. The green plot represents the FSC between averages of two half data sets from an individual reconstruction. The red plot represents the global average of six reconstructions. This data shows that there is better correspondence between motifs from a given crystal than between two different crystals, due to differences in unit cell parameters and to the particular buildup of negative stain around each individual crystal. This is also evident from data in Table I. Applying a criteria of 0.5 to the red plot, the resolution for the final model was estimated to be ~2.4 nm.

Table I.

Comparison of data sets with the Fourier Shell Coefficient

| Tube1 | Tube2 | Tube3 | Tube4 | Tube5 | Tube6 | Final

averaged structure |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tube1 | 3.0a | 2.8 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 5.0 | 2.6 |

| Tube2 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 5.2 | 2.5 | |

| Tube3 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 4.5 | ||

| Tube4 | 2.7 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.8 | |||

| Tube5 | 2.8 | 4.4 | 3.5 | ||||

| Tube6 | 2.5 | 5.0 | |||||

| Final averaged structure | 2.4 |

Values in the table correspond to the resolution in nm at which the Fourier shell coefficient reaches a value of 0.5.

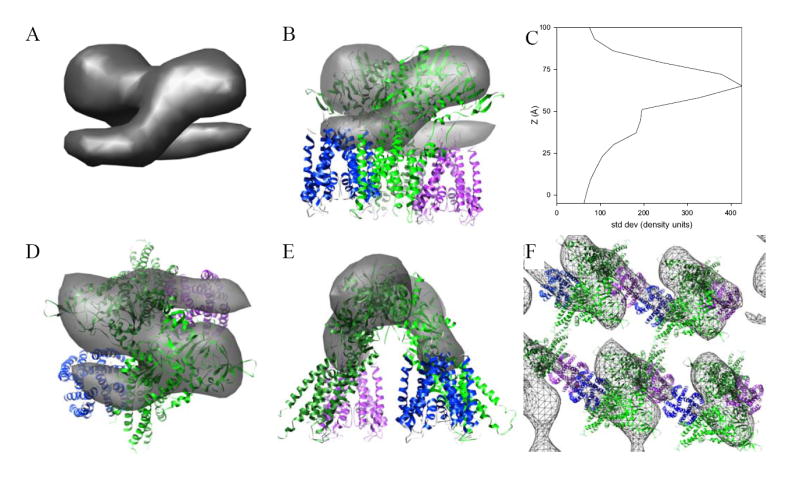

3.4. Kdp dimers form the asymmetric unit

The map consists of a series of strong, ellipsoidal densities that form tightly coupled dimers and are connected to the membrane by a stalk. These structures are associated with tubular shaped elements running parallel to the membrane surface (Figs. 3 and 5A). The dimensions of each ellipsoid are consistent with the predicted size of the cytoplasmic domains of KdpB, but the extent of the map densities normal to the membrane plane suggests that the membrane domains are not visible. There is precedent for a loss of contrast within the transmembrane region of negatively stained samples, which is presumably due to a lack of penetration by the uranyl salt within the hydrophobic core of the bilayer. In particular, the contrast in the final 3D map along the membrane normal is plotted in Fig. 5c and shows a region of high contrast extending for ~60 Å with a region of much lower contrast to one side. The region of lower contrast extends for an additional 40-50 Å in what we believe to be the region of the membrane bilayer where, at lower density thresholds, uninterpretable density is present. Kdp does not have any appreciable mass on the extracellular side of the membrane and it is therefore not surprising that no corresponding density is seen in our map. This distribution of contrast is quite similar to that observed by Taylor et al. (Taylor et al., 1986) for negatively stained membrane crystals of Ca2+-ATPase, which is a related member of the P-type ATPase family. On the other hand, it is not clear how our 3D map correlates with the previous projection structure of Kdp (Iwane et al., 1996). Although both crystallization conditions included vanadate and low K+ concentrations, the previous work used microsomes isolated directly from bacterial membranes without detergent solubilization, purification and reconstitution; furthermore the Q116R mutant was used in this previous study, instead of the wild type enzyme employed for our current work. The crystal packing of the two crystal forms are quite different: p1 vs. p2 symmetry with rather different unit cell parameters (66 × 47 Å with γ=110° compared to 100.5 × 121.9 with γ=116.6° for the current crystals). In addition to these sample-related differences, ambiguities in interpreting projection structures, especially for negatively stained samples with variable stain penetration, makes it difficult to compare these two structures in any definitive way.

Figure 5. Fitting a model for Kdp to the tomographic map.

(A) The asymmetric unit has been masked from the unit cell and shown in a view parallel to the membrane surface. Overall height of this structure is 6-7 nm and appears to consist of a symmetric dimer. (B) Fitting of pseudoatomic models for KdpA and KdpB to this dimeric structure. The KdpA model corresponds to the published X-ray crystal structure of KcsA (blue and magenta) and the KdpB model has been based on an X-ray crystallographic structure of Ca2+-ATPase in the E2 enzymatic state with several deletions (light and dark green). This view is parallel to the membrane surface. (C) Plot of contrast present in the tomographic reconstruction along the membrane normal. Contrast was defined as the standard deviation of densities within each 0.7-nm section from the final averaged structure. (D) Top view, normal to the membrane plane, of the fitted structure shown in (B). (E) View of the structure in (B) rotated 90° about the vertical axis. (F) View of the crystal lattice normal to the membrane. Although the dimer is mediated by interactions between cytoplasmic domains of KdpB subunits, the crystal lattice is mediated in the horizontal direction by interactions between KdpA subunits and in the vertical direction by the membrane domain, which are not visible in this map.

3.4. Kdp subunit organization

Although the absence of the membrane domain prevents a detailed modeling of Kdp structure, the shape of the cytoplasmic domains allows us to evaluate the juxtaposition of the major Kdp subunits within the 2D array. KdpB is homologous to the catalytic subunit of other P-type ATPases and shares a common domain architecture as well as key sequence motifs (Lutsenko and Kaplan, 1995, Moller et al., 1996). Thus, like Ca2+-ATPase and Na+/K+-ATPase, KdpB is likely to be dominated by a pear-shaped cytoplasmic domain that is connected to the membrane by a narrower stalk. Indeed, Fig. 5 shows that the ellipsoidal densities are fit reasonably well by the cytoplasmic domains from a homology model for KdpB. In contrast, KdpA has structural and functional similarities to the pore-forming helices of K+ channels, such as KcsA (Durell et al., 2000) and is expected to consist predominantly of transmembrane helices with only relatively small loops on the cytoplasmic surface. Thus, the KdpA subunit has been placed next to KdpB along the tubular densities that run parallel to the membrane surface, which we hypothesize to be the cytoplasmic loops of KdpA. Packing this model into the crystal lattice suggests a number of intermolecular contacts responsible for stabilizing this lattice (Fig. 5F). In particular, the unit cell contains a dimer of Kdp, which appears to be mediated by a contact between N-domains of KdpB. Interestingly, there is some evidence that the functional unit of Kdp is a dimer (A2B2C2, Altendorf et al., 1992, Laimins et al., 1981), though we can not be certain about the functional relevance of the crystallographic dimer seen in our maps. Along one unit cell axis (horizontal in Fig. 5F), these dimers are linked via the tubular densities, which we believe to be KdpA subunits. Additional interactions along the vertical direction in Fig. 5F are not visible in our map and could involve interactions between the membrane domains of KdpB, KdpC or KdpF.

3.5. Conclusions

These results illustrate the utility of electron tomography for structure determination of crystalline assemblies, when strict crystallographic symmetry is perturbed either by specimen preparation or by innate disorder. In our case, the use of negative stain caused partial flattening of an otherwise helical assembly and real-space averaging of individual, 3D unit cells proved to be an effective way to produce an averaged 3D structure. This approach has also been effectively applied to disordered arrays of myosin V assembled on lipid sheets (Liu et al., 2006), when crystalline disorder was too severe for Fourier-based crystallographic image processing packages. The standard crystallographic approach generally begins with determination of a projection structure, which then provides a phase reference for adding images from tilted crystals. In contrast, this tomographic approach has the advantage of producing a 3D structure from the outset, which can be useful in evaluating molecular packing and crystal symmetry (Stokes et al., 2006). Such a structure could also represent a phase reference for further crystallographic analysis. Indeed, considering the relative ease of determining a 3D structure by electron tomography and the effectiveness of real-space averaging in boosting the signal-to-noise ratio, tomography should be considered a viable alternative in structure determination of 2D crystals.

Acknowledgments

This work relied on the instrumentation resources for electron tomography at New York Structural Biology Center, which is a STAR center supported by the New York State Office of Science, Technology, and Academic Research. The work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM56590 to D.L.S.) and a fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG- Forschungsstipendium DR 400/1-1 to S.D.).

References

- Altendorf K, Siebers A, et al. The KDP ATPase of Escherichia coli. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1992;671:228–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb43799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand J, Altendorf K, et al. Amino acid substitutions in putative selectivity filter regions III and IV in KdpA alter ion selectivity of the KdpFABC complex from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:5519–5522. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.16.5519-5522.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buurman ET, Kim KT, et al. Genetic evidence for two sequentially occupied K+ binding sites in the Kdp transport ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6678–6685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRosier DJ, Moore PB. Reconstruction of three-dimensional images from electron micrographs of structures with helical symmetry. J Mol Biol. 1970;52:355–369. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle DA, Cabral JM, et al. The structure of the potassium channel: molecular basis of K+ conduction and selectivity. Science. 1998;280:69–77. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durell SR, Bakker EP, et al. Does the KdpA subunit from the high affinity K+-translocating P-type KDP-ATPase have a structure similar to that of K+ channels? Biophys J. 2000;78:188–199. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76584-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein W. The roles and regulation of potassium in bacteria. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2003;75:293–320. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(03)75008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein W, Davies M. Potassium-dependant mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1970;101:836–843. doi: 10.1128/jb.101.3.836-843.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendler K, Drose S, et al. Electrogenic K+ transport by the Kdp-ATPase of Escherichia coli. Biochem. 1996;35:8009–8017. doi: 10.1021/bi960175e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J, Radermacher M, et al. SPIDER and WEB: processing and visualization of images in 3D electron microscopy and related fields. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:190–199. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassel M, Altendorf K. Analysis of KdpC of the K+-transporting KdpFABC complex of Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:1772–1781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassel M, Mollenkamp T, et al. The KdpF subunit is part of the K+-translocating Kdp complex of Escherichia coli and is responsible for stabilization of the complex in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37901–37907. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassel M, Siebers A, et al. Assembly of the Kdp complex, the multi-subunit K+-transport ATPase of Escherichia coli. Bioch Biophys Acta. 1998;1415:77–84. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green NM. ATP-driven Cation Pumps: Alignment of Sequences. Biochem Soc Trans. 1989;17:970–972. doi: 10.1042/bst0170972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt M, Bramkamp M, et al. Inter-domain motions of the N-domain of the KdpFABC complex, a P-type ATPase, are not driven by ATP-induced conformational changes. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:1547–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse JE, Wieczorek L, et al. Sequence homology between two membrane transport ATPases, the Kdp-ATPase of Escherichia coli and the Ca2+-ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 1984;81:4746–4750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.15.4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwane AH, Ikeda I, et al. Two-dimensional crystals of the Kdp-ATPase of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1996;396:172–176. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AM, Sorensen TL, et al. Modulatory and catalytic modes of ATP binding by the calcium pump. EMBO J. 2006;25:2305–2314. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, et al. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laimins LA, Rhoads DB, et al. Osmotic control of kdp operon expression in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1981;78:464–468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Taylor DW, et al. Three-dimensional structure of the myosin V inhibited state by cryoelectron tomography. Nature. 2006;442:208–211. doi: 10.1038/nature04719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludtke SJ, Baldwin PR, et al. EMAN: semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J Struct Biol. 1999;128:82–97. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutsenko S, Kaplan JH. Organization of P-type ATPases: significance of structural diversity. Biochem. 1995;34:15607–15613. doi: 10.1021/bi00048a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde DN. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J Struct Biol. 2005;152:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller JV, Juul B, et al. Structural organization, ion transport, and energy transduction of P-type ATPases. Bioch Biophys Acta. 1996;1286:1–51. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(95)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller JV, Olesen C, et al. The structural basis for coupling of Ca2+ transport to ATP hydrolysis by the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2005;37:359–364. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-9471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, et al. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoads DB, Laimins L, et al. Functional organization of the kdp genes of Escherichia coli K-12. J Bacteriol. 1978;135:445–452. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.2.445-452.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader M, Fendler K, et al. Replacement of glycine 232 by aspartic acid in the KdpA subunit broadens the ion specificity of the K+-translocating KdpFABC complex. Biophys J. 2000;79:802–813. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76337-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes DL, Pomfret AJ, et al. Interactions between Ca2+-ATPase and the pentameric form of phospholamban in two-dimensional co-crystals. Biophys J. 2006;90:4213–4223. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.079640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani K, Sasabe H, et al. A set of computer programs for determining defocus and astigmatism in electron images. Ultramicroscopy. 1996;65:31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KA, Dux L, et al. Three-dimensional reconstruction of negatively stained crystals of the Ca++-ATPase from muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Mol Biol. 1986;187:417–427. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima C, Nakasako M, et al. Crystal structure of the calcium pump of sarcoplasmic reticulum at 2.6 Å resolution. Nature. 2000;405:647–655. doi: 10.1038/35015017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin PNT, Henderson R. Molecular structure determination by electron microscopy of unstained crystalline specimens. J Mol Biol. 1975;94:425–440. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Laan M, Gassel M, et al. Characterization of amino acid substitutions in KdpA, the K+-binding and -translocating subunit of the KdpFABC complex of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:5491–5494. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.19.5491-5494.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heel M, Harauz G, et al. A new generation of the IMAGIC image processing system. J Struct Biol. 1996;116:17–24. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler H, Taylor KA. Accurate marker-free alignment with simultaneous geometry determination and reconstruction of tilt series in electron tomography. Ultramicroscopy. 2006;106:240–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]