Abstract

The etiology of hypertension historically includes two components, genetics and lifestyle. However, recent epidemiological studies report an inverse relationship between birth weight and hypertension suggesting that a suboptimal fetal environment may also contribute to increased disease in later life. Experimental studies support this observation and indicate that cardiovascular/kidney disease originates in response to fetal adaptations to adverse conditions during prenatal life.

Keywords: fetal programming, hypertension, kidney, experimental models

INTRODUCTION TO FETAL PROGRAMMING

The fetal environment is considered a key factor in the etiology of cardiovascular disease later in life. The theory that experiences in early life exert a major influence on cardiovascular risk was first reported by Dr Anders Forsdahl in 1973. Dr. Forsdahl's studies initiated the theory that poor social conditions could serve as an adverse stimulus during childhood and adolescence leading to increased risk for cardiovascular disease in adulthood (1). Dr. David Barker advanced the concept by suggesting that the influences that lead to increased cardiovascular risk may have their origins in prenatal life. Both of these original observations noted a strong positive correlation between coronary heart disease and infant mortality. However, Dr. Barker first noted the inverse relationship between weight at birth and risk of cardiovascular disease (2), formulating the fetal environment as a new component in the etiology of cardiovascular disease. Based on his observations, Barker hypothesized that developmental programming of adult disease occurs in response to an imbalance during fetal life between fetal demands and nutrient supply resulting in fetal undernutrition (3). Impairment in fetal development, which can be marked by intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and low birth weight, results from these fetal adaptations to an adverse fetal environment leading to molecular and physiological adaptive changes (4). Although these fetal adaptations allow fetal survival, they also results in long-term consequences such as marked alterations in the physiology and structure of the cardiovascular, renal, metabolic, respiratory, endocrine, and nervous systems (4-6). Acceptance of the theory of fetal programming has met with skepticism due to the inability of many epidemiological studies to separate the contribution of confounding variables including socioeconomic and social factors, in addition to, genetic factors, catch-up growth, and current BMI (7). However, experimental approaches using animal models that initiate an insult during a crucial period of fetal life provide critical support for Barker's initial hypothesis and importantly, insight into the mechanisms linking birth weight and blood pressure (8-12). Thus, the theory of fetal programming has emerged as a very new and exiting field for investigation, due to not only to its novelty, but also due to controversy surrounding the interpretation of epidemiological studies.

ANIMAL MODELS OF FETAL PROGRAMMING OF ADULT DISEASE

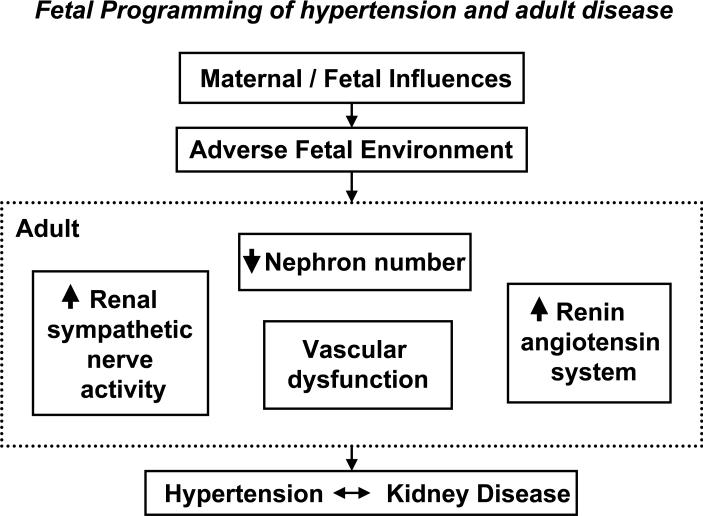

Investigators utilizing animal models to induce an adverse fetal environment and mimic the human condition of slow fetal growth are elucidating the mechanistic pathways implicated in the developmental programming of adult disease (5, 13-16). Different methods have been utilized to induce a suboptimal fetal environment in experimental studies. Despite subtle differences in the method of insult, common outcomes are observed (FIGURE 1) and demonstrate characteristics reflective of the human condition of slow fetal growth including asymmetric fetal growth restriction (4), decreased nephron number (17), impaired vascular function (18), and significant elevations in blood pressure (3).

FIGURE 1.

An adverse fetal environment due to either maternal or fetal influences leads to impaired kidney development and common adaptive alterations in systems critical to the long-term control of blood pressure resulting in hypertension and increased risk for kidney disease later in life.

MANIPULATION OF MATERNAL CONDITIONS

I. Models of dietary manipulation

Fetal programming as hypothesized by Barker involves adaptive responses by the fetus to undernutrition. One of the most common models, dietary manipulation, involves global nutritional or isocaloric protein undernutrition administered during gestation (8-10, 12). Common adaptive outcomes include IUGR associated with reduced nephron number (8-10, 12), altered vascular function (19), and increased blood pressure (8-10, 12), an effect that is not species specific.

Investigators utilizing models of gestational protein undernutrition demonstrate that the timing of the insult during gestation is critical to the fetal adaptive response. In the rat, marked changes in kidney morphology and increases in blood pressure are observed when the nutritional insult coincides with nephrogenesis. However, the same insult initiated prior to the nephrogenic period does not alter kidney structure or blood pressure regulation (8, 20). Since the kidneys are known to play a major role in the long-term regulation of arterial pressure (21), these studies suggest that an insult during kidney development leads to ‘programming’ of the kidneys resulting in an abnormal outcome in the complex mechanisms associated with blood pressure regulation.

II. Models of reduced utero-placental perfusion

Fetal nutrition induced by impairment of utero-placental perfusion is a model of fetal programming utilized to mimic the human condition of IUGR marked by asymmetric fetal growth restriction (22). Placental insufficiency is the common consequence in these models which results in deprivation of nutrient and oxygen delivery to the fetus (11, 23, 24). Common adaptive outcomes observed in response to placental insufficiency include reduced nephron number (23), altered vascular reactivity (25), cardiovascular remodeling (24), and marked increases in blood pressure (11).

IV. Models of hypoxia

Exposure during gestation to acute or chronic hypoxia is also used to mimic conditions leading to slow fetal growth (26-28). Reduced litter size and birth weight are common features of this model and hypoxia, as an insult during fetal development, leads to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular remodeling (26, 27). Findings from this model have provided insight into the importance of suppression of growth related genes and induction of inflammation related genes in the etiology of IUGR (28, 29).

V. Models of pharmacological manipulation

Pharmacological manipulation during pregnancy is another model used to induce an adverse fetal environment to mimic the pathophysiological conditions linked to IUGR. 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11B-HSD2), an enzyme which inactivates cortisol thus serving as a barrier for fetal exposure to maternal glucocorticoids, is decreased in pregnancies complicated by IUGR (30). Pre-natal exposure to glucocorticoids or the 11B-HSD2 inhibitor, carbenoxolone, leads to reductions in birth weight (31-34), reduced nephron number (33), glucose intolerance (34), and programmed hypertension (32, 33). Interestingly, these effects are transmitted to the next generation despite further exposure to glucocorticoids suggesting the potential involvement of epigenetic mechanisms (34)

MANIPULATION OF THE FETUS

I. Models of uninephrectomy

Uninephrectomy in an adult does not normally lead to changes in kidney function and blood pressure (35). However, uninephrectomy during the nephrogenic period leads to marked elevations in blood pressure and greater severity of kidney damage in later life (36-38).

II. Models of pharmacological blockade

The renin angiotensin system (RAS) is highly expressed in the kidney during development and plays a critical role in mediating proper nephrogenesis (39). RAS blockade during nephrogenesis in the rat leads to permanent alterations in kidney function and structure associated with significant increases in blood pressure (40-42).

III. Models of genetic manipulation

Gene deletion is another method utilized to induce a sub-optimal fetal environment and IUGR. Genetic mouse models are used to study mechanisms associated with metabolic disorders related to growth restriction, and alterations related to altered nitric oxide (NO) synthesis and metabolism (43-46).

COMMON MECHANSTIC PATHWAYS IN FETAL PROGRAMMING

Although the methods used to induce a fetal insult may vary in animal studies, common fetal adaptive responses are observed. These include not only common adult disease outcomes, but also similar alterations in the mechanistic pathways that lead to chronic adult disease.

I. Fetal programming of the sympathetic nervous system

Blood flow re-distribution is one of the first adaptative changes observed in response to fetal insult. Blood flow to critical organs such as the brain and heart is spared at the expense of other organs such as liver, kidney, muscles and skin (47) resulting in fetal hypoxia with alterations in the hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) pathway (48). HIF, a transcription factor, influences several regulatory pathways including the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) via stimulation of tyrosine hydroxylase (48). In humans sympathetic activation is observed in low birth weight individuals, and is increased in response to hypoxia in animals (49-52). Increased circulating catecholamines are also reported in numerous models of fetal programming induced by placental insufficiency as well as gestational protein restriction (53-55). Recent studies demonstrate that the renal nerves play a critical role in the etiology of hypertension programmed by placental insufficiency (56). Therefore, hypoxia may serve as a stimulus for increased renal sympathetic nerve activity leading to hypertension.

II. Fetal programming of the renin angiotensin system

Animals models of fetal programming induced by gestational protein undernutrition and placental insufficiency report common temporal alterations in the RAS (9, 57, 58). Suppression of the intrarenal RAS at birth (9, 57) is followed by later activation of the RAS including increased expression of renal AT1 receptors (59, 60) and renal ACE (12, 57). Importantly, blockade of the RAS prevents or abolishes hypertension in offspring of protein restricted or reduced uterine perfusion dams, thus demonstrating the importance of the RAS in the etiology of programmed hypertension (57, 61-63).

III. Fetal programming of nephron number

Impairment in nephrogenesis resulting in reduced nephron number is a common outcome of fetal programming observed in many different animal models, and also in human studies associated with IUGR (9, 10, 16, 17, 24, 64, 65). Increases in renal apoptosis and expression of key apoptosis genes may contribute to reduced nephron number programmed by fetal insult (10, 24). These adaptive changes during fetal programming point to the kidney as a critical target for fetal programming, and emphasize the importance of the kidney in the long-term regulation of blood pressure control.

IV. Fetal programming of vascular dysfunction

Vascular dysfunction plays a critical role in the development of cardiovascular disease (65). Impaired endothelial function is observed in clinical studies of low birth weight including studies performed in healthy children (18) suggesting that vascular consequences of fetal programming precede the development of adult cardiovascular disease. Animal models of fetal programming induced by nutritional restriction, placental insufficiency, and hypoxia report endothelial dysfunction associated with reduced NO availability (19, 25, 67-69). Treatment with the antioxidants, vitamins C and E, improve vascular function (70) suggesting altered NO bioavailability linked to increased oxidative stress contributes to vascular dysfunction programmed by fetal insult.

CONCLUSIONS

Human studies indicate that slow fetal growth is linked to increased risk for adult disease. Animal studies demonstrate that adverse conditions during fetal development lead to permanent alterations in the structure and physiology of the fetus influencing disease outcome in later life. Furthermore, animal studies are beginning to elucidate alterations in common mechanistic pathways intrinsic in the fetal programming of adult disease.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Forsdahl A. Observations throwing light on the high mortality in the county of Finnmark. Is the high mortality today a late effect of very poor living conditions in childhood and adolescence? 1973. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker DJ, Winter PD, Osmond C, et al. Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet. 1989;2:577–580. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90710-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker DJ, Osmond C. Low birth weight and hypertension. Bmj. 1988;297:134–135. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6641.134-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker DJ. Intrauterine programming of adult disease. Mol Med Today. 1995;1:418–423. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(95)90793-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nathanielsz PW. Animal models that elucidate basic principles of the developmental origins of adult diseases. Ilar J. 2006;47:73–82. doi: 10.1093/ilar.47.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fowden AL, Giussani DA, Forhead AJ. Intrauterine programming of physiological systems: causes and consequences. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:29–37. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00050.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huxley RR, Shiell AW, Law CM. The role of size at birth and postnatal catch-up growth in determining systolic blood pressure: a systematic review of the literature. J Hypertens. 2000;18:815–831. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langley-Evans SC, Welham SJ, Jackson AA. Fetal exposure to a maternal low protein diet impairs nephrogenesis and promotes hypertension in the rat. Life Sci. 1999;64:965–974. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woods LL, Ingelfinger JR, Nyengaard JR, et al. Maternal protein restriction suppresses the newborn renin-angiotensin system and programs adult hypertension in rats. Pediatr Res. 2001;49:460–467. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vehaskari VM, Aviles DH, Manning J. Prenatal programming of adult hypertension in the rat. Kidney Int. 2001;59:238–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander BT. Placental insufficiency leads to development of hypertension in growth-restricted offspring. Hypertension. 2003;41:457–462. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000053448.95913.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert JS, Lang AL, Grant AR, et al. Maternal nutrient restriction in sheep: hypertension and decreased nephron number in offspring at 9 months of age. J Physiol. 2005;565:137–147. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander BT. Fetal programming of hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1–R10. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00417.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langley-Evans SC. Fetal programming of cardiovascular function through exposure to maternal undernutrition. Proc Nutr Soc. 2001;60:505–513. doi: 10.1079/pns2001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vehaskari VM, Woods LL. Prenatal programming of hypertension: lessons from experimental models. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2545–2556. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005030300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moritz KM, Dodic M, Wintour EM. Kidney development and the fetal programming of adult disease. Bioessays. 2003;25:212–220. doi: 10.1002/bies.10240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughson MD, Douglas-Denton R, Bertram JF, et al. Hypertension, glomerular number, and birth weight in African Americans and white subjects in the southeastern United States. Kidney Int. 2006;69:671–678. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodfellow J, Bellamy MF, Gorman ST, et al. Endothelial function is impaired in fit young adults of low birth weight. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;40:600–606. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brawley L, Itoh S, Torrens C, et al. Dietary protein restriction in pregnancy induces hypertension and vascular defects in rat male offspring. Pediatr Res. 2003;54:83–90. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000065731.00639.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods LL, Weeks DA, Rasch R. Programming of adult blood pressure by maternal protein restriction: role of nephrogenesis. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1339–1348. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyton AC, Coleman TG, Cowley AV, Jr, et al. Arterial pressure regulation. Overriding dominance of the kidneys in long-term regulation and in hypertension. Am J Med. 1972;52:584–594. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(72)90050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernstein I, GS, Reed KL. Intrauterine growth restriction. Obstetrics, Normal and Problem Pregnancies. In: Gabbe JNSG, Simpson JL, editors. Churchill Livingstone; Philadelphia, PA: 2002. pp. 869–891. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pham TD, MacLennan NK, Chiu CT, et al. Uteroplacental insufficiency increases apoptosis and alters p53 gene methylation in the full-term IUGR rat kidney. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R962–970. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00201.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murotsuki J, Challis JR, Han VK, et al. Chronic fetal placental embolization and hypoxemia cause hypertension and myocardial hypertrophy in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R201–207. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.1.R201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Payne JA, Alexander BT, Khalil RA. Reduced endothelial vascular relaxation in growth-restricted offspring of pregnant rats with reduced uterine perfusion. Hypertension. 2003;42:768–774. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000084990.88147.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Longo LD, Pearce WJ. Fetal cerebrovascular acclimatization responses to high-altitude, long-term hypoxia: a model for prenatal programming of adult disease? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R16–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00462.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornburg KL. Hypoxia and cardiac programming. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2003;10:251. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5576(03)00106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tapanainen PJ, Bang P, Wilson K, et al. Maternal hypoxia as a model for intrauterine growth retardation: effects on insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins. Pediatr Res. 1994;36:152–158. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199408000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang ST, Vo KC, Lyell DJ, et al. Developmental response to hypoxia. Faseb J. 2004;18:1348–1365. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1377com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shams M, Kilby MD, Somerset DA, et al. 11Beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 in human pregnancy and reduced expression in intrauterine growth restriction. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:799–804. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.4.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindsay RS, Lindsay RM, Edwards CR, et al. Inhibition of 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in pregnant rats and the programming of blood pressure in the offspring. Hypertension. 1996;27:1200–1204. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.6.1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woods LL, Weeks DA. Prenatal programming of adult blood pressure: role of maternal corticosteroids. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R955–962. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00455.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dickinson H, Walker DW, Wintour EM, et al. Maternal dexamethasone treatment at midgestation reduces nephron number and alters renal gene expression in the fetal spiny mouse. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;292:R453–461. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00481.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drake AJ, Walker BR, Seckl JR. Intergenerational consequences of fetal programming by in utero exposure to glucocorticoids in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R34–38. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00106.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Narkun-Burgess DM, Nolan CR, Norman JE, et al. Forty-five year follow-up after uninephrectomy. Kidney Int. 1993;43:1110–1115. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moritz KM, Wintour EM, Dodic M. Fetal uninephrectomy leads to postnatal hypertension and compromised renal function. Hypertension. 2002;39:1071–1076. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000019131.77075.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Celsi G, Bohman SO, Aperia A. Development of focal glomerulosclerosis after unilateral nephrectomy in infant rats. Pediatr Nephrol. 1987;1:290–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00849226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woods LL, Weeks DA, Rasch R. Hypertension after neonatal uninephrectomy in rats precedes glomerular damage. Hypertension. 2001;38:337–342. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guron G, Friberg P. An intact renin-angiotensin system is a prerequisite for normal renal development. J Hypertens. 2000;18:123–137. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guron G. Renal haemodynamics and function in weanling rats treated with enalapril from birth. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32:865–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2010.04278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woods LL, Rasch R. Perinatal ANG II programs adult blood pressure, glomerular number and renal function in rats. Am J Physiol Regulatory Integrative Comp Physiol. 1998;275:R1593–R1599. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.5.R1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loria A, Reverte V, Salazar F, et al. Changes in renal hemodynamics and excretory function induced by a reduction of ANG II effects during renal development. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R695–700. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00191.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crossey PA, Pillai CC, Miell JP. Altered placental development and intrauterine growth restriction in IGF binding protein-1 transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:411–418. doi: 10.1172/JCI10077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamemoto H, Kadowaki T, Tobe K, et al. Insulin resistance and growth retardation in mice lacking insulin receptor substrate-1. Nature. 1994;372:182–186. doi: 10.1038/372182a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Longo M, Jain V, Vedernikov YP, et al. Fetal origins of adult vascular dysfunction in mice lacking endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1114–1121. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00367.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang A, Sun D, Yan C, et al. Contribution of 20-HETE to augmented myogenic constriction in coronary arteries of endothelial NO synthase knockout mice. Hypertension. 2005;46:607–613. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000176745.04393.4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Golding J, et al. Growth in utero, blood pressure in childhood and adult life, and mortality from cardiovascular disease. Bmj. 1989;298:564–567. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6673.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leclere N, Andreeva N, Fuchs F, et al. Hypoxia-induced long-term increase of dopamine and tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA levels. Prague Med Rep. 2004;105:291–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.IJzerman RG, Stehouwer CD, de Geus EJ, et al. Low birth weight is associated with increased sympathetic activity: dependence on genetic factors. Circulation. 2003;108:566–571. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000081778.35370.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boguszewski MC, Johannsson G, Fortes LC, et al. Low birth size and final height predict high sympathetic nerve activity in adulthood. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1157–1163. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200406000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rouwet EV, Tintu AN, Schellings MW, et al. Hypoxia induces aortic hypertrophic growth, left ventricular dysfunction, and sympathetic hyperinnervation of peripheral arteries in the chick embryo. Circulation. 2002;105:2791–2796. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000017497.47084.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ruijtenbeek K, le Noble FA, Janssen GM, et al. Chronic hypoxia stimulates periarterial sympathetic nerve development in chicken embryo. Circulation. 2000;102:2892–2897. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.23.2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hiraoka T, Kudo T, Kishimoto Y. Catecholamines in experimentally growth-retarded rat fetus. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;17:341–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1991.tb00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones CT, Robinson JS. Studies on experimental growth retardation in sheep. Plasma catecholamines in fetuses with small placenta. J Dev Physiol. 1983;5:77–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Petry CJ, Dorling MW, Wang CL, et al. Catecholamine levels and receptor expression in low protein rat offspring. Diabet Med. 2000;17:848–853. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alexander BT, Hendon AE, Ferril G, et al. Renal denervation abolishes hypertension in low-birth-weight offspring from pregnant rats with reduced uterine perfusion. Hypertension. 2005;45:754–758. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153319.20340.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grigore D, Ojeda NB, Robertson EB, et al. Placental insufficiency results in temporal alterations in the renin angiotensin system in male hypertensive growth restricted offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R804–811. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00725.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Riviere G, Michaud A, Breton C, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and ACE activities display tissue-specific sensitivity to undernutrition-programmed hypertension in the adult rat. Hypertension. 2005;46:1169–1174. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000185148.27901.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sahajpal V, Ashton N. Renal function and angiotensin AT1 receptor expression in young rats following intrauterine exposure to a maternal low-protein diet. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;104:607–614. doi: 10.1042/CS20020355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vehaskari VM, Stewart T, Lafont D, et al. Kidney angiotensin and angiotensin receptor expression in prenatally programmed hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F262–267. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00055.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ojeda NB, Grigore D, Yanes LL, et al. Testosterone contributes to marked elevations in mean arterial pressure in adult male intrauterine growth restricted offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R758–763. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00311.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sherman RC, Langley-Evans SC. Antihypertensive treatment in early postnatal life modulates prenatal dietary influences upon blood pressure in the rat. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000;98:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manning J, Vehaskari VM. Low birth weight-associated adult hypertension in the rat. Pediatr Nephrol. 2001;16:417–422. doi: 10.1007/s004670000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bauer R, Walter B, Ihring W, et al. Altered renal function in growth-restricted newborn piglets. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14:735–739. doi: 10.1007/pl00013427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mitchell EK, Louey S, Cock ML, et al. Nephron endowment and filtration surface area in the kidney after growth restriction of fetal sheep. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:769–773. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000120681.61201.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Panza JA, Quyyumi AA, Brush JE, Jr, et al. Abnormal endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in patients with essential hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:22–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007053230105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alves GM, Barao MA, Odo LN, et al. L-Arginine effects on blood pressure and renal function of intrauterine restricted rats. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17:856–862. doi: 10.1007/s00467-002-0941-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Franco Mdo C, Arruda RM, Dantas AP, et al. Intrauterine undernutrition: expression and activity of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase in male and female adult offspring. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;56:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00508-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Williams SJ, Hemmings DG, Mitchell JM, et al. Effects of maternal hypoxia or nutrient restriction during pregnancy on endothelial function in adult male rat offspring. J Physiol. 2005;565:125–135. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Franco Mdo C, Akamine EH, Aparecida de Oliveira M, et al. Vitamins C and E improve endothelial dysfunction in intrauterine-undernourished rats by decreasing vascular superoxide anion concentration. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;42:211–217. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200308000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]