Abstract

We have established a differential peptide display method, based on a mass spectrometric technique, to detect peptides that show semiquantitative changes in the neurointermediate lobe (NIL) of individual rats subjected to salt-loading. We employed matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry, using a single-reference peptide in combination with careful scanning of the whole crystal rim of the matrix-analyte preparation, to detect in a semiquantitative manner the molecular ions present in the unfractionated NIL homogenate. Comparison of the mass spectra generated from NIL homogenates of salt-loaded and control rats revealed a selective and significant decrease in the intensities of several molecular ion species of the NIL homogenates from salt-loaded rats. These ion species, which have masses that correspond to the masses of oxytocin, vasopressin, neurophysins, and an unidentified putative peptide, were subsequently chemically characterized. We confirmed that the decreased molecular ion species are peptides derived exclusively from propressophysin and prooxyphysin (i.e., oxytocin, vasopressin, and various neurophysins). The putative peptide is carboxyl-terminal glycopeptide. The carbohydrate moiety of the latter peptide was determined by electrospray tandem MS as bisected biantennary Hex3HexNAc5Fuc. This posttranslational modification accounts for the mass difference between the predicted mass of the peptide based on cDNA studies and the measured mass of the mature peptide.

Keywords: matrix-assisted laser desorption–ionization-MS, electrospray ionization-MS, collision-induced dissociation, carbohydrate moiety, neurointermediate lobe

For cell-to-cell signaling, neurons commonly employ multiple peptides that are derived from one precursor or various precursors. Because neuronal input may control the expression of peptide genes as well as the processing and release of mature peptides, changes in neuronal input may lead to alterations of the cellular pattern of bioactive peptides, resulting in adjustments of physiological processes and behavior (1, 2). To characterize the changes in peptide patterns, a method is needed that can detect the cellular profile of peptides as well as the changes in the relative levels of individual peptides. We propose to call such a method a “differential peptide display method,” in analogy to similar methods (e.g., the differential display polymerase chain reaction; see ref. 3 and references therein) employed in molecular biological research to detect genes that show altered expression during development or after application of a physiological stimulus. MS offers unique opportunities for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of a peptide mixture (4) and has been used to tentatively detect previously identified peptides in neuroendocrine tissue (5–7). Furthermore, MS can reveal the presence of unpredicted components (i.e., analytes with masses that do not correspond to those of previously described peptides; refs. 5 and 7). Finally, tandem MS can provide amino acid sequence information for predicted as well as novel peptides (8). Among the several soft-ionization MS techniques available, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization MS (MALDI-MS) is particularly attractive, because it tolerates impurities, is sensitive (low femtomole sensitivity), and can detect peptides directly in tissue without prior purification (7, 9). Unfortunately, due to the nonuniform nature of the matrix-analyte preparation, direct quantitative analysis of biological samples by MALDI-MS has proven to be difficult, and this fact has hampered experiments designed to study the physiological significance of changes in peptide profiles.

We now demonstrate the feasibility of a differential peptide display method that employs semiquantitative MALDI-MS screening by using the neurointermediate lobe (NIL) of the rat as a convenient and well established experimental neuroendocrine preparation, of which the peptides have been previously identified (see ref. 10 and references therein). By including a single-reference peptide that is not related to the peptides known to be present in the NIL, in combination with extensive scanning of the crystal rim of the matrix-analyte preparation, we show that the levels of several molecular ions with masses corresponding to the peptides derived from propressophysin and prooxyphysin (see Fig. 1; ref. 11) and the level of an unidentified molecule with a protonated mass of 5,930 Da in the NIL were significantly decreased in salt-loaded rats. Neurophysins, vasopressin, and oxytocin were purified using their masses as molecular markers to guide their purification. Their identities were confirmed by Edman sequencing, in some cases in conjunction with enzymatic degradation and MS analysis. The peptide component of the unidentified protonated mass of 5,930 Da was established by amino acid sequencing of the purified material as carboxyl-terminal glycopeptide (CPP) of propressophysin. The major carbohydrate moiety of CPP was determined by electrospray ionization (ESI) tandem MS as a bisected biantennary Hex3HexNAc5Fuc, and a minor form was determined as Hex4HexNAc5Fuc2.

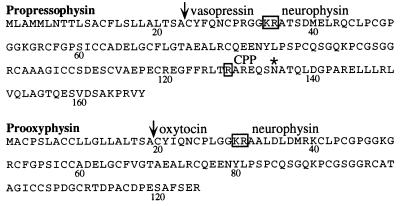

Figure 1.

Predicted amino acid sequence of precursor proteins of bioactive peptides present in the NIL of the rat. Shown are propressophysin (11) and prooxyphysin (11), as derived from their corresponding cDNA data. Proteolytic cleavage sites are boxed. The vertical arrows indicate the signal sequence cleavage sites. Numbers indicate amino acid residue positions. ∗, putative glycosylation site in the CPP domain of propressophysin. CPP, carboxyl-terminal glycopeptide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, Cell Dissociation, and Sample Preparation.

In the salt-loading experiment, five rats had free access to tap water for 8 days (control rats), and five rats had free access to 2% NaCl in tap water for 8 days (salt-loaded rats). Pituitaries of the five control rats and the five salt-loaded rats were dissected immediately after decapitation of each animal, and the NILs were dissected free from the anterior pituitaries, as previously described (12). Dissection of a pituitary and a NIL took less than 3 min. Immediately after dissection, each NIL was separately homogenized in 40 μl methanol, kept on ice, and stored at −40°C until analysis by MALDI-MS.

MALDI-MS Analysis of Tissue Homogenates.

One-half microliter of a 40-μl methanol homogenate of the dissected entire NIL (tissue/methanol ratio is 5:1 vol/vol) of each animal was transferred to 1 μl matrix [10 mg 2,5-dihydroxy-benzoic acid (DHB) and 1 mg 2-methoxy-5-benzoic acid dissolved in 1 ml 7.5 mM trifluoroacetic acid/30% acetonitrile] on a stainless-steel target. The sample was dried by a stream of cool air and analyzed using a laboratory-built laser desorption/ionization reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometer equipped with a pulsed nitrogen laser (337 nm; pulse width, 3 ns). Upon drying, the analyte molecules are intercalated into the matrix crystals that form on the rim of the DHB matrix-analyte preparation. Especially in complex biological mixtures, the analytes may not be evenly distributed in each crystal, resulting in microheterogeneity of analyte concentrations in different spots of the crystal rim. The sample preparation procedure does not induce artifactual modifications of amino acid residues (13).

For semiquantitative measurements of the NIL homogenates of the control and salt-loaded rats, a reference peptide (a synthetic molluscan peptide: SADSAPSSANEVQRF) was added to the matrix in a concentration (10 pmol/μl) that yielded peak intensities in the order of the peak intensities observed for the abundant analytes. The mass of the reference peptide (1,565.6 Da) does not overlap with those of the peptides contained in the NIL. Furthermore, the addition of the reference peptide at this concentration does not alter the MS peptide profiles of the NIL homogenate (data not shown). The advantage of adding the reference peptide is that it allows correction for crystallization variability inherent to MALDI sample preparations. Moreover, to average out microheterogeneity in different matrix crystals of the same sample, two samples of 0.5 μl of each homogenate from an individual NIL were measured by means of extensive scanning of each sample; i.e., the spectra were generated from all over the crystal rim of the matrix/analyte preparation (10 spectra per irradiated spot; laser spot size, 200 μm) and were summed up to a total of 150 shots per sample. This procedure yielded an average sum spectrum that covered in total about one-third of the whole crystal rim. Single NIL homogenates from five control and five salt-loaded rats were individually measured by MALDI-MS. Angiotensin, melittin, insulin, and cytochrome c were used for external mass calibration of the NIL peptides. The accuracy of the mass measurements was in the range of 0.05–0.1%.

Peptide Purification.

Three NILs from control rats were dissected and collected on solid carbon dioxide. The pooled NILs were homogenized, extracted by boiling in 0.1 M acetic acid for 8 min, and centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was immediately fractionated using RP-HPLC carried out on a liquid chromatograph system (Gynkotech, Munich) with a Nucleosil C18 column (5 μm, 250 × 2.1 mm). Peptides were resolved and eluted with an increasing acetonitrile concentration in 7.5 mM trifluoroacetic acid. The HPLC fractions were screened by MALDI-MS. Fractions containing the molecules of interest were either subjected to Edman degradation or further purified with the Nucleosil C18 column, using 0.05% heptafluorobutyric acid as a counter ion and an increasing gradient of acetonitrile to elute the peptides. The amino acid sequences of the purified peptides were determined.

The purified neurophysins were digested by endoproteinase Lys-C, as previously described (14). The digestion products were resolved by RP-HPLC and analyzed by MS and Edman sequencing as described above.

Amino Acid Sequence Analysis.

The amino acid sequences of the purified molecules were established by automated Edman degradation in a Model 473 pulse liquid-phase sequencer (Perkin–Elmer/Applied Biosystems).

Oligosaccharide Release.

Purified CPP (ca. 200 pmol) was dissolved in 200 μl phosphate buffer (20 mM, pH 7.2). Oligosaccharide release using N-glycanase and subsequent permethylation was carried out, as previously described (15).

ESI Tandem MS.

The spectra for characterization of the permethylated carbohydrate moiety of CPP were acquired with a Finnigan-MAT (San Jose, CA) TSQ 700 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer system fitted with an Analytica ESI source (Branford, CT). The ion source temperature was set at 150°C. The sample was dissolved in methanol/water (6:4 vol/vol) containing 0.25 mM NaOH, and the solution was introduced in the electrospray chamber at 0.85 μl/min. Low-energy collision-induced dissociation (CID) of ions was effected with argon at 2 mTorr at kinetic energies of 60–80 eV (for accelerating voltages of 30–40 V).

RESULTS

The Differential Peptide Display Method, Using Semiquantitative MALDI-MS Peptide Profiling of NIL, Demonstrates Selective Decrease After Salt-Loading of Peptides Derived from Propressophysin and Prooxyphysin.

We explored the possibility of obtaining semiquantitative information, by using MALDI-MS, on the relative changes in the levels of peptides in individual NILs from rats subjected to salt-loading as compared with control rats. The MALDI-MS analysis of each NIL was carried out in duplo using 0.5-μl samples of the unfractionated methanol homogenate of 40 μl of each NIL. These independent in duplo measurements of each NIL homogenate yielded reproducible mass spectra (see examples in Fig. 2A and B). NIL homogenates from five salt-loaded rats and five control rats were separately measured to yield average values and standard deviations.

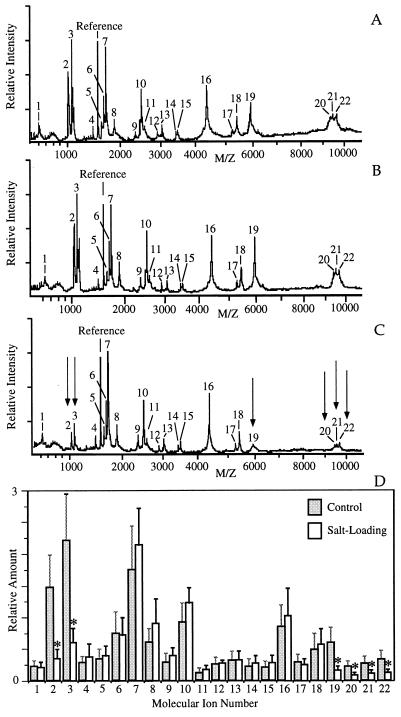

Figure 2.

Effect of salt-loading on the MALDI-MS peptide profile of the rat NIL. (A and B) Shown are the two MALDI-mass spectra, representing in duplo measurements, using two 0.5-μl samples of a 40-μl unfractionated methanol homogenate of the NIL from a control rat. (C) Representative example of a MALDI-MS analysis of the NIL of a salt-loaded rat. Arrows indicate mass peaks whose signal intensities have decreased, as compared with the control situation (cf. the spectra in A and B). (D) Average levels (relative to the reference peptide) of molecular ions in NIL extracts of five control rats and five salt-loaded rats. Error bars indicate standard deviations and are calculated based on values derived from the measurements of single NILs from individual rats. The relative amounts of molecular ions indicated by an asterisk are significantly decreased (P < 0.05, Student’s t test) in the salt-loaded NILs, as compared with the control NILs. The molecular ions are numbered, starting with the peaks representing the lowest protonated mass. Peaks: 1, 608.3 Da; 2, 1,007.5 Da; 3, 1,085.5 Da; 4, 1,458.2 Da; 5, 1,623 Da; 6, 1,666 Da; 7, 1,708 Da; 8, 1,884 Da; 9, 2,360 Da; 10, 2,507 Da; 11, 2,587 Da; 12, 2,902 Da; 13, 3,039 Da; 14, 3,437 Da; 15, 3,480 Da; 16, 4,386 Da; 17, 5,262 Da; 18, 5,418 Da; 19, 5,930 Da; 20, 9,363 Da; 21, 9,491 Da; and 22, 9,681 Da. The molecular ions that showed decreased levels after salt-loading (ions 2, 3, 20, 21, and 22) have masses that match those of prooxyphysin- and propressophysin-derived peptides. An unidentified putative peptide (5,930 Da, ion 19) is reduced as well. Ion 2 (oxytocin) and ion 3 (vasopressin) were also detected as cationized species. x axis, m/z mass-to-charge ratio; y axis, intensity in arbitrary units.

Fig. 2C shows an example of a mass profile of a NIL homogenate of a salt-loaded rat. Comparison of Fig. 2 A and B with C reveals that the levels of six molecular ions (see below) were decreased. To obtain the relative quantities of the molecular ions in the spectra obtained from the NILs of the five control and five salt-loaded rats, the peak height of each component peptide was divided by the peak height of the reference peptide. Fig. 2D shows that the relative amounts of the molecular ion species numbered 2, 3, 19, 20, 21, and 22 in the spectra of Fig. 2 A–C had significantly (P < 0.05, Student’s t test) decreased in the salt-loaded animals to, respectively, 24.0 ± 7.7%, 27.8 ± 11.6%, 28.8 ± 11.7%, 36.6 ± 11.8%, 35.9 ± 9.4%, and 34.7 ± 10.2% of the control values. The decreased molecular ions have masses that match the masses of peptides derived from propressophysin and prooxyphysin [i.e., calculated vs. measured protonated mass: ion 2 (oxytocin), m/z 1,008.2 vs. 1,007.5; ion 3 (vasopressin), m/z 1,085.3 vs. 1,085.5; ion 20 (prooxyphysin-derived neurophysin carboxyl-terminally truncated by the Glu and Arg residues), m/z 9,357 vs. 9,363; ion 21 (prooxyphysin-derived neurophysin carboxyl-terminally truncated by the Arg residue), m/z 9,486 vs. 9,491; and ion 22 (propressophysin-derived neurophysin), m/z 9,680 vs. 9,681]. In addition, the level of an unidentified putative peptide (ion 19) with a measured protonated mass of 5,930 Da was significantly reduced.

The six molecules that showed decreased levels in the spectra of salt-loaded rats (see Fig. 2C) were isolated by RP-HPLC from an acetic acid homogenate of three pooled NILs obtained from control rats. The molecules with masses corresponding to oxytocin and vasopressin were present in fractions 25 and 20, respectively (Fig. 3A). Edman sequencing confirmed their identities as oxytocin, [C]YIQN[C]PLG and vasopressin, [C]YFQN[C]PRG, where cysteine residues were detected as blank cycles. Comparison of the measured masses of the peptides and their calculated masses based on Edman sequencing data revealed a mass difference of 3 Da, which is consistent with the presence of a disulfide bond and a carboxyl-terminal amidation in each of these peptides.

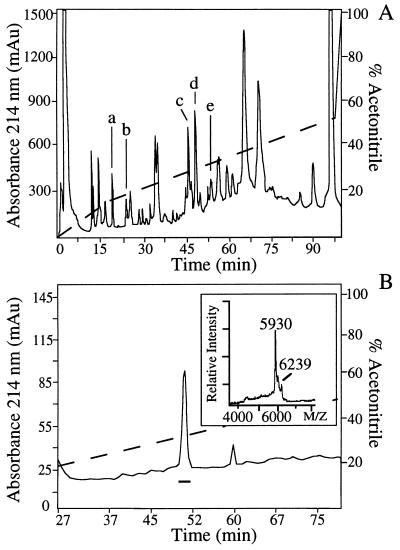

Figure 3.

Purification of peptides from the NIL by RP-HPLC. (A) RP-HPLC of an acetic acid extract of NIL using trifluoroacetic acid as a counter ion. The fractions were screened by MALDI-MS, and material in fraction 55 (peak e) contained a molecule at m/z 5,930 (corresponding in mass to ion 19 in the mass spectra of Fig. 2) that was subjected to further purification. Also indicated are the elution positions of neurophysins at fractions 47, 48, and 50 (peaks c and d) that correspond in mass to ions 21, 20, and 22 (Fig. 2), respectively, and oxytocin and vasopressin at fractions 25 and 20 (peaks a and b) that correspond in mass to ions 2 and 3 of Fig. 2, respectively. (B) Second RP-HPLC purification with material of fraction 55 purified in A, using heptafluorobutyric acid as a counter ion. Fraction 52 of the second RP-HPLC step contained a major component at m/z 5,930 (box in Fig. 3B), which was subjected to amino acid sequence analysis. In addition, the structures of the posttranslational modification of the components at m/z 5,930 and m/z 6,239 were examined by CID tandem MS (see Fig. 4). The presence of the shoulder on the m/z 5,930 peak could be attributed to an experimental artifact (i.e., the signal arising from secondary ions generated during postacceleration of the electron signal for the m/z 5,930 peak). In A and B, acetonitrile gradients are indicated by dashed lines.

The two putative carboxyl-terminally truncated forms of prooxyphysin-derived neurophysin and the entire propressophysin-derived neurophysin (corresponding to ions 20, 21, and 22, respectively, in Fig. 2) were present as well in the RP-HPLC fractions (Fig. 3A). Indeed, Edman sequencing of the molecule in RP-HPLC fraction 50 at m/z 9,681 (corresponding to ion 22 in Fig. 2) revealed the amino-terminal sequence of ATSDMELRQ… , which corresponds to that of neurophysin (calculated protonated mass, 9,680 Da) derived from propressophysin (11). The mass spectra of fractions 47 and 48 contained molecular ions at m/z 9,491 (ion 21 in Fig. 2) and m/z 9363 (ion 20 in Fig. 2), respectively. These fractions were separately subjected to Edman sequencing, which revealed that the peptides had the same amino terminus: AALDLDMRK… , and, therefore, represent different forms of neurophysin derived from prooxyphysin that are presumably truncated at the carboxyl terminal (11). The peptides were separately digested by endoproteinase Lys-C, and the fragments were resolved by HPLC (data not shown). The masses of the digested fragments were measured by MALDI-MS, and the peptides with masses corresponding to the expected carboxyl-terminal-located digested fragments from ion 20 and ion 21, respectively, were subjected to Edman degradation, which revealed the same partial amino acid sequence of P[C]GSGGR[C]ATAGI[C][C]SPDG[C]R… (cf. Fig. 1), where cysteine residues were detected as blank cycles. The measured protonated masses of the carboxyl-terminally located digested fragments of ion 20 of 3,193 Da and of ion 21 of 3,322 Da agree with the calculated protonated masses of 3,194 Da and 3,323 Da, respectively, of the corresponding carboxyl-terminal fragments, where two (Glu-Arg) and one (Arg) amino acid residues, respectively, are trimmed off at the carboxyl terminus of neurophysin derived from prooxyphysin. The carboxyl-Arg-trimmed form of neurophysin is the major form present in the NIL, whereas full-length neurophysin derived from prooxyphysin is not detected.

Using two RP-HPLC steps, the molecule with a protonated mass of 5,930 Da was purified (Fig. 3 A and B). Edman degradation yielded the amino acid sequence AREQS[N]ATQLDGPARELLLRLVQLAGTQESVDSAKPRVY, which represents the primary structure of CPP (cf. Fig. 1; ref. 11). The sixth residue, expected to be Asn (11), was not detected during Edman sequencing, suggesting that this residue is posttranslationally modified. This modification is consistent with the observation that the Asn residue occurs in a consensus sequence for N-glycosylation (11, 16) (see below). The minor peak at m/z 6,239 (box in Fig. 3B) represents heterogeneity in the carbohydrate moiety of CPP (see below).

Glycosylated CPP Has a Carbohydrate Moiety of Hex3HexNAc5Fuc.

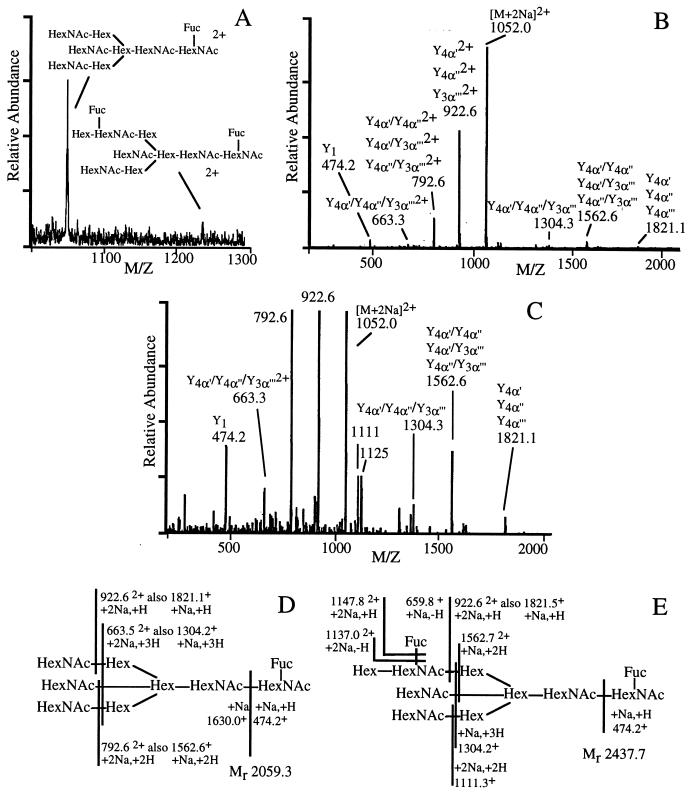

The difference between the calculated mass of CPP (4,283 Da), based on the above amino acid sequence data and the cDNA data (cf. Fig. 1), and the measured mass (m/z 5,930; cf. Figs. 2 and 3B) suggests that the Asn at position 6 is used for N-linked glycosylation. To investigate this possibility and to assign a structure to the oligosaccharide moieties, N-glycanase digestion was carried out on purified CPP (≈200 pmol). The released oligosaccharide pool was permethylated and examined by ESI tandem MS. This method is useful for profiling glycoprotein oligosaccharides at high sensitivity (17). The permethylated oligosaccharides are observed in the ESI tandem mass spectrum with multiple cation attachments. These adducts result in a series of peaks for each species: [M+Na]+, [M+2Na]2+, etc., of which the doubly cationized form is usually the most abundant for glycomers of the size encountered in this case. Because the mass spectrum is measured as m/z values, the charge state of the ions can be determined from the spacing of the peaks within the isotope cluster (e.g., for a doubly charged species, the 13C-labeled isotope peaks are spaced at 0.5 mass-unit intervals).

The ESI mass spectrum of the permethylated products (Fig. 4A) shows two peaks in the region in which oligosaccharides would be expected. The more abundant peak was observed at m/z 1,052.6, corresponding to the [M+2Na]2+ ions for a component with molecular mass of 2,059.3 Da and a lower abundance peak at m/z 1,241.0, corresponding to the [M+2Na]2+ with molecular mass of 2,437.7 Da. These oligosaccharides can be assigned the compositions Hex3HexNAc5Fuc and Hex4HexNAc5Fuc2, whose residue mass increments to a peptide would be 1,648.5 and 1,956.7 Da, respectively. The calculated weight for the CPP glycosylated with Hex3HexNAc5Fuc would be 5,930.3 Da. This mass is consistent with the abundant [M+H]+ at m/z 5,930 observed in the MALDI-MS spectrum (box in Fig. 3B). The higher-mass oligosaccharide would yield a glycopeptide with molecular mass of 6,238 Da, calculated [M+H]+ 6,239, and can thus be assigned to the low-abundance peak in the MALDI-MS spectrum (box in Fig. 3B). Each of the peaks in the ESI mass spectrum that corresponded to the [M+2Na]2+ ions from the permethylated oligosaccharides was subjected to CID. The product ion spectra contained singly and doubly charged fragments that arose via glycosidic cleavages. The CID spectrum of the major oligosaccharide is shown in Fig. 4 B and C. The glycoform structures and the carbohydrate fragment ion types, on which these assignments are based, are indicated in Fig. 4 D and E, according to the nomenclature system of Domon and Costello (18). The Y-type ions originate via glycosidic cleavages accompanied by hydrogen transfer to the observed reducing end fragment. Designations a′, a′′, and a′′′ signify the branches in a multiantennary structure. The data are sufficient to specify the oligosaccharide molecular masses, residue sequences, and branching patterns, but not the linkage sites.

Figure 4.

Characterization of the carbohydrate moiety of CPP. (A) ESI mass spectrum of the oligosaccharide moiety permethylated after release from ca. 200-pmol CPP-containing fraction (see Fig. 3B). (B) Low-energy electrospray CID mass spectrum of [M+2Na]2+, m/z 1,052.0, the major oligosaccharide in the pool permethylated after release from CPP. (C) Y-scale expansion of the CID spectrum of B. (D and E) Assignments of the product ions from [M+2Na]2+, m/z 1,052.0 (D) and m/z 1,241.0 (E) in the ESI mass spectrum of CPP-permethylated oligosaccharides.

DISCUSSION

The differential peptide display method described here consists of three steps, namely (i) the generation of mass profiles from homogenates of a neuroendocrine tissue (i.e., the NIL of rat), (ii) the comparison of the mass profiles of the NIL homogenates from two groups of rats that have free access to water and salt water, respectively, with the aim to reveal the molecular ion species that exhibit changes in intensity, and (iii) the identification of molecular ion species that show altered levels.

The essence of the method is the semiquantitative detection by MALDI-MS of the spectrum of putative peptides in neuroendocrine tissue. The sample preparation procedure that was used in our experiments favorably detects peptides and is less effective in detecting cellular constituents such as phospholipids and structural proteins (19). However, the standard preparation for MALDI-MS using DHB is characterized by a nonuniform matrix/analyte deposition, which results often in poorly reproducible signal responses of varying intensities (20). Therefore, a reference peptide was added to the matrix to correct for shot-to-shot variability and crystallization variability between samples. Moreover, an average sum spectrum was acquired by carefully scanning the crystal rim of the DHB–matrix/analyte preparation to average out possible microheterogeneities among crystals. In this way, the average sum spectra acquired for stimulated and control rats allowed us to characterize in a (semi-)quantitative way the changes in the amounts of NIL peptides relative to the reference peptide.

We detected several molecular ions that showed significantly decreased levels in the NIL of salt-loaded rats. The six decreased molecules could be assigned as peptides derived from prooxyphysin and propressophysin. Neurophysin derived from prooxyphysin appeared further truncated. Based on cDNA studies (11), the carboxyl-terminal residue of neurophysin derived from prooxyphysin is an Arg. It has been proposed (11) that this residue would be readily trimmed off by carboxyl-peptidase E, the enzyme in the secretory granules that removes the carboxyl-terminal Arg and/or Lys residues from the propeptide, resulting in the formation of the mature peptide. Indeed, the major form of prooxyphysin-derived neurophysin detected in the present study is the one lacking the carboxyl-Arg residue, whereas the full-length neurophysin was not detected. In addition, a truncated form of this neurophysin lacking two carboxyl-terminal amino acids (i.e., Glu-Arg) was also detected, suggesting that another (form of) carboxyl-peptidase may be involved in trimming off these residues. The molecule with a protonated mass of 5,930 Da did not correspond to any peptide previously described; therefore, we conducted an extensive structural analysis. Edman sequencing yielded the full-length amino acid sequence of the molecule, which corresponds to the primary structure of CPP. The fact that the sixth residue, which is expected to be Asn (11), was not detected is consistent with the prediction that this residue constitutes the N-linked glycosylation site (11, 16) and that this modification would give a blank cycle during Edman sequencing. We then confirmed that CPP is glycosylated, the major carbohydrate moiety being bisected biantennary Hex3HexNAc5Fuc.

In the NIL of salt-loaded rats, the peptides derived from prooxyphysin and propressophysin decreased to 25–35% of the control levels, which agrees nicely with radioimmunoassay data (21) that determined a decrease in the oxytocin and vasopressin levels to 30% of the control values following salt-loading.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the North Atlantic Treaty Organization for a grant (900605) to C.E.C., and Dr. R. Kingston from Micromass (Manchester, U.K.) for his technical assistance. This study has been supported by an apparatus grant to K.W.L. and W.P.M.G. from the Foundation for the Life Sciences, which is a subsidiary of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: DHB, 2,5-dihydroxy-benzoic acid; ESI, electrospray ionization; CID, collision-induced dissociation; CPP, C-terminal glycopeptide of propressophysin; MALDI, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization; NIL, neurointermediate lobe.

References

- 1.Kupfermann I. Physiol Rev. 1991;71:683–731. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.3.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leibowitz S F. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;739:12–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb19804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang P, Pardee A B. Curr Opin Immunol. 1995;7:274–280. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(95)80015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siuzdac G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11290–11297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feistner G J, Hojrup P, Evans C J, Barofsky D F, Faull K F, Roepstorff P. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6013–6017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.16.6013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feistner G J, Faull K F, Barofsky D F, Roepstorff P. J Mass Spectrom. 1995;30:519–530. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiménez C R, Van Veelen P A, Li K W, Wildering W C, Geraerts W P M, Tjaden U R, Van der Greef J. J Neurochem. 1994;62:404–407. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62010404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medzihradszky K F, Burlingame A L. Companion Methods Enzymol. 1994;6:284–303. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Strien F J C, Jespersen S, Van der Greef J, Jenks B G, Roubos E W. FEBS Lett. 1996;379:165–170. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01503-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loh Y P. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;44:843–849. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivell R, Richter D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2006–2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.7.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keja J A, Stoof J C, Kits K S. J Physiol. 1992;450:409–435. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li K W, Geraerts W P M. Methods Mol Biol. 1997;72:219–223. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-394-5:219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De With N D, Van der Schors R C, Boer H H, Ebberink R H M. Peptides. 1993;14:783–789. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(93)90114-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciucanu I, Kerek K. Carbohydr Res. 1984;131:209–217. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seidah N G, Benjannet S, Chrétien M. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1981;100:901–902. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(81)80258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinhold, V. N., Reinhold, B. B. & Costello, C. E. Anal. Chem. 67, 1772–1784. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Domon B, Costello C E. Glycoconjugate J. 1988;5:397–409. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li K W, Hoek R M, Smith F, Jiménez C R, Van der Schors R C, Van Veelen P A, Chen S, Van der Greef J, Benjamin P R, Parish D, Geraerts W P M. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30288–30292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson R W, McLean M A, Hutchens T W. Anal Chem. 1994;66:1408–1415. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Tol H H M, Voorhuis D, Th A M, Burbach J P H. Endocrinology. 1987;120:71–76. doi: 10.1210/endo-120-1-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]