Abstract

Deleted in liver cancer 1 (DLC-1), as its name implied, was originally isolated as a potential tumor suppressor gene often deleted in hepatocellular carcinoma. Further studies have indicated that down-expression of DLC-1 either by genomic deletion or DNA methylation is associated with a variety of cancer types including lung, breast, prostate, kidney, colon, uterus, ovary, and stomach. Re-expression of DLC-1 in cancer cells regulates the structure of actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesions and significantly inhibits cell growth, supporting its role as a tumor suppressor. This tumor suppressive function relies on DLC-1’s RhoGAP activity and START domain, as well as its focal adhesion localization, which is recruited by the SH2 domains of tensins in a phosphotyrosine-independent fashion. Therefore, the expression and subcellular localization of DLC-1 could be a useful molecular marker for cancer prognosis, whereas DLC-1 and its downstream signaling molecules might be therapeutic targets for the treatment of cancer.

Keywords: DLC, tumor suppressor, focal adhesion

Introduction

DLC-1 (deleted in liver cancer 1, also known as ARHGAP7 and STARD12 in human and p122RhoGAP in rat) was first isolated from rat brain as a phospholipase Cδ1(PLCδ1) binding protein (Homma and Emori, 1995) and then was independently cloned by subtractive hybridization as a gene homozygously deleted in a human hepatocellular carcinoma (Yuan et al., 1998). Together with its gene locus at human chromosome 8p21, a region frequently deleted in liver cancer, DLC-1 is considered as a potential tumor suppressor. Evidence is now emerging to demonstrate that DLC-1 is a focal adhesion molecule that plays a role in preventing cell transformation in the liver as well as many other tissues.

Structure

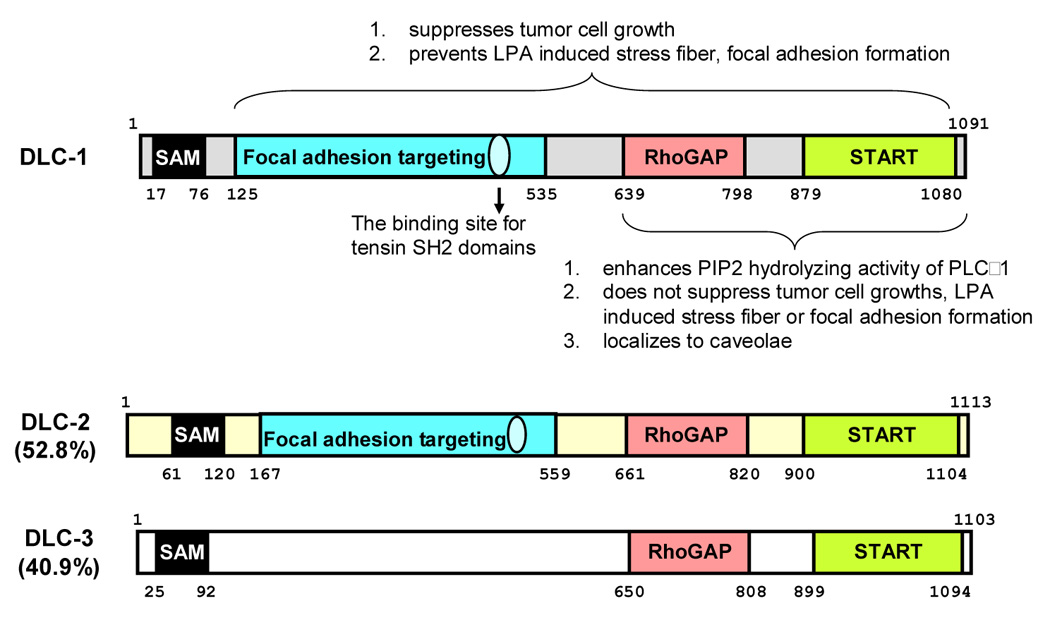

DLC-1 was also named ARHGAP7 and STARD12 because it contains a RhoGAP (RhoGTPase activating protein) domain and a START (steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR)-related lipid transfer) domain, respectively. In addition, a SAM (sterile alpha motif) domain is found near its N-terminus (figure 1). SAM domains are known to interact with each other forming homodimers. In other cases, they may bind to other proteins, RNA, or DNA (Qiao and Bowie, 2005). However, the function for DLC-1’s SAM domain remains to be characterized. START domains are predicted to interact with lipids (Iyer et al., 2001) and yet need to be confirmed for DLC-1’s START domain. RhoGAP domains convert the active GTP-bound Rho proteins to the inactive GDP-bound state and negatively regulate Rho GTPases. The N-terminal region of DLC-1 contains a focal adhesion targeting sequence that binds to the SH2 (Src Homology 2) domains of focal adhesion proteins, tensins, and is therefore recruited to these sites (Liao et al., 2007). This focal adhesion localization of DLC-1 appears to be critical for its tumor suppressive function. SH2 domains are binding motifs for phosphotyrosine. Surprisingly, the interaction between DLC-1 and tensin’s SH2 domain is independent to tyrosine phosphorylation of DLC-1. This SH2-DLC-1 interaction was demonstrated by yeast-two-hybrid, co-immunoprecipitation, pull-down, peptide binding, and subcellular localization assays (Liao et al., 2007). By mutagenesis approaches, critical residues including serine-440 and tyrosine-442 on DLC-1 as well as arginine residue at βB5 position of SH2 domains of tensins were identified (Liao et al., 2007). However, the same region of DLC-1 was reported to interact with the PTB (PhosphoTyrosine Binding), but not the SH2, domain of tensin2 (Yam et al., 2006). These contradictive results remain to be investigated.

Figure 1. Functional and structural domains of DLCs.

DLC-1 contains a SAM, RhoGAP and START domain. A focal adhesion targeting (FAT) region in the N-terminal half and a binding site for the SH2 domains of tensin family have been identified in DLC-1. The SAM domain is not required for DLC-1’s function in suppressing cell growth or actin fiber and focal adhesion formation. The C-terminal half of DLC-1 contains the RhoGAP and START domains and binds to PLCδ1. This C-terminal region is necessary but not sufficient for inhibiting tumor cell growth, actin fiber and focal adhesion formation. It also requires the FAT fragment for DLC-1’s tumor suppression activity. Overall, human DLC-2 and DLC-3 amino acid sequences share 52.8% and 40.9% identities to that of DLC-1. The SAM, RhoGAP and START domains are highly conserved. The corresponding FAT regions in DLC-2 and DLC-3 show 38.8% and 21.3% identities, and the focal adhesion localization has been confirmed for DLC-2 but not DLC-3.

The C-terminal half of DLC-1 interacts with PLCδ1 and enhances the phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate (PIP2)-hydrolyzing activity of PLCδ1 (Homma and Emori, 1995). This PLCδ–enhancing activity may contribute to the role of DLC-1 in regulating the actin stress fibers (see Biological function). The C-terminal region also targets to caveolae presuming by interacting with caveolin-1 through several potential binding sites on DLC-1 (Yam et al., 2006; Yamaga et al., 2004). However, the significance of caveolae localization of DLC-1 is not clear.

Expression and regulation

DLC-1 is expressed in many normal tissues including brain, heart, kidney, liver, lung, skin, spleen, and testis (Durkin et al., 2002). As mentioned, human DLC-1 was identified as a candidate tumor suppressor and in agreement with this notion, its expression was lost or down-regulated in various cancers including liver, breast, lung, brain, stomach, colon and prostate cancers due to either genomic deletion or aberrant DNA methylation (table 1) (Guan et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2000; Plaumann et al., 2003; Seng et al., 2007; Song et al., 2006; Ullmannova and Popescu, 2006; Wong et al., 2003; Yuan et al., 2003a; Yuan et al., 2004; Yuan et al., 1998). These results also suggest that DLC-1 may function as a tumor suppressor in tissues other than liver. Interestingly, dietary flavone is able to restore the expression of DLC-1 in some cancer cell lines that are DLC-1-negative due to DNA hypermethylation (Ullmannova and Popescu, 2007), suggesting a potential preventive and therapeutic benefits of flavone in some DLC-1 related cancers.

Table 1.

Expression analyses of DLC-1 in various types of cancers.

| Tumor tissues | Carcinoma cell lines | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | 95% (20 of 21) | 58% (11 of 19) | Yuan et al., 2004 |

| 90% (total: 21) | Ullmannova and Popescu, 2006 | ||

| Ovary | 79% (total: 14) | Ullmannova and Popescu, 2006 | |

| Breast | 76% (total: 50) | Ullmannova and Popescu, 2006 | |

| 71% (12 of 17) | Yuan et al., 2003 | ||

| 57% | 63% | Plaumann et al., 2003 | |

| Kidney | 75% (total: 20) | Ullmannova and Popescu, 2006 | |

| Uterus | 64% (total: 42) | Ullmannova and Popescu, 2006 | |

| Colon | 43% (total: 35) | Ullmannova and Popescu, 2006 | |

| 71% (12 of 17) | Yuan et al., 2003 | ||

| Stomach | 41% (total: 27) | Ullmannova and Popescu, 2006 | |

| 78% (7 of 9) | Kim et al., 2003 | ||

| Prostate | 37% (10 of 27) | 60% (3 of 5) | Guan et al., 2006 |

| Rectum | 28% (total: 18) | Ullmannova and Popescu, 2006 | |

| Liver | 44% (7 of 16) | 91% (10 of 11) | Yuan et al., 1998 |

| 68% (27 of 40) | 43% (3 of 7) | Wong et al., 2003 | |

| 20% (6 of 30) | 40% (2 of 5) | Ng et al., 2000 | |

| 18% (2 of 11) | Kim et al., 2007 | ||

| Nasopharynx | 91% (11 of 12) | Seng et al., 2007 | |

| Cervix | 63% (5 of 8) | Seng et al., 2007 | |

| Esophagus | 40% (6 of 15) | Seng et al., 2007 | |

Biological function

Studies have demonstrated that re-expression of DLC-1 in liver, breast, lung cancer cell lines inhibits cancer cell growth (Goodison et al., 2005; Wong et al., 2005; Yuan et al., 2004; Yuan et al., 2003b; Zhou et al., 2004), supporting its major role as a tumor suppressor. The suppressive function may attribute to several known regulatory activities of DLC-1 such as the regulation of actin cytoskeleton, focal adhesion formation, and cell shape (Sekimata et al., 1999), as well as induction of apoptosis (Zhou et al., 2004). Rat DLC-1 binds to PLCδ1 and enhances the hydrolysis of PIP2 (Homma and Emori, 1995; Sekimata et al., 1999), which is known to modulate actin cytoskeleton in multiple ways (Yin and Janmey, 2003). The hydrolysis of PIP2 leads to the generation of diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) that activates protein kinase C and induces Ca2+ release from internal stores, respectively. Both protein kinase C and Ca2+ are regulators of actin cytoskeleton (Yin and Janmey, 2003). In addition, many actin-regulating proteins such as profilin, cofilin, and gelsolin bind to PIP2 and the hydrolysis of PIP2 will result in the release of these proteins and, in turn, bind to G-actin or the ends of actin filaments and accelerate the disassembly of actin fibers (Yin and Janmey, 2003). This PLCδ1-enhancing activity of DLC-1 may act synergistically with its RhoGAP activity in inducing the cytoskeletonal and morphological changes. Previous studies showed that the C-terminal half of DLC-1, which binds to PLCδ1 and contains the RhoGAP activity and START domain, is necessary for inhibiting tumor cell growth, actin fiber and focal adhesion formation (figure 1) (Sekimata et al., 1999; Wong et al., 2005; Yam et al., 2006). However, this C-terminal region of DLC-1 alone is not sufficient for these functions (Wong et al., 2005). Indeed, recent studies have indicated that in addition to the RhoGAP activity and START domain, tensin-binding activity is essential for its growth suppression activity (Liao et al., 2007). The significance of this tensin-binding activity is to target DLC-1 to focal adhesion sites. DLC-1 mutants disrupted the interaction with tensins are not able to localize to focal adhesions and lose their suppression activities (Liao et al., 2007).

In addition to the tumor suppressor activity, one report has defined DLC-1 as a metastasis suppressor in breast cancer cells (Goodison et al., 2005). In this study, the gene expression profiles of metastatic and non-metastatic sublines of the parental MDA-MB-435 breast cancer cell line were compared and DLC-1 was down-expressed in the metastatic subline. Restoration of DLC-1 in metastatic cell line leads to the inhibition of migration and invasion in cell culture assays and a significant reduction in metastases in nude mouse experiments (Goodison et al., 2005).

DLC-1 may also be involved in insulin signaling. Insulin induces the phosphorylation on serine-322 of rat DLC-1 (serine-329 in human DLC-1)(Hers et al., 2006). It was suggested that insulin-stimulated serine-322 phosphorylation could be regulated by either the PI-3 kinase/AKT pathway or the MEK/ERK/ribosomal S6 kinase pathway depending on the cell types. Although the function of this serine phosphorylation is currently unknown, it does not regulate the focal adhesion localization of DLC-1 (Hers et al., 2006).

The knockout mouse studies have indicated an essential role for DLC-1 in mouse embryonic development (Durkin et al., 2005). Homozygous mutant embryos die before 10.5 days postcoitus with defects in the neural tube, brain, heart, and placenta (Durkin et al., 2005). Fibroblasts isolated from DLC-1 mutant embryos contain disrupted actin filaments and fewer focal adhesions (Durkin et al., 2005). The embryonic fibroblast study results confirmed the role of DLC-1 in regulating actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesion structures. However, the early lethality of DLC-1 null embryos limited further study on its role as a tumor suppressor. The tissue specific deletion of DLC-1 in mice will provide more information on its roles in various cancers and may provide good animal models for those relevant human cancers.

Two molecules with extensive homology to DLC-1 have been isolated (figure 1). DLC-2 (STARD13) gene locates at human chromosome 13q12, while DLC-3 (STARD8, KIAA0189) gene is at human Xq13, Both contains the SAM, RhoGAP and START domains, although one of alternative spliced forms of DLC-3 does not contain the SAM domain (Durkin et al., 2007). Down-regulation of DLC-2 and DLC-3 were also reported in various human cancers and the colony formation assay showed that both DLC-2 and DLC-3 inhibited tumor cell growth (Ching et al., 2003; Durkin et al., 2007; Leung et al., 2005). In addition, we and others found the N-terminal half of DLC-2 localized to focal adhesions (Liao and Lo, unpublished data; Hers et al., 2006). Other report showed that the START domain of DLC-2 targeted to mitochondria (Ng et al., 2006).

Possible Medical and Industrial Applications

As a tumor suppressor, understanding DLC-1’s functions and its signaling pathways are crucial for both prevention and treatment of DLC-1 related cancer. DLC-1 and its downstream signaling molecules can be useful biomarkers for prediction and diagnosis as well as targets for therapeutic interventions in cancer. Downregulation of DLC-1 expression either by genomic deletion or DNA methylation and DLC-1 protein mislocalization could be indicators for tumor progression. Being a target in the insulin pathway implies that DLC-1 may be involved in glucose uptake and its abnormal expression may lead to diseases such as diabetes. Both possibilities are not established and warrant further analyses. The multiple involvements of DLC-1 in a variety of tissues expand its potential medical applications. The tissue specific DLC-1 null mice may provide good models for various cancers and diseases. Once more detailed biological functions of DLC-1 and its signaling pathway are revealed, it is possible to develop drugs to restore or enhance DLC-1’s function in diseased cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH/NCI (CA102537) and Shriners Hospitals Research Award (8580).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ching YP, Wong CM, Chan SF, Leung TH, Ng DC, Jin DY, Ng IO. Deleted in liver cancer (DLC) 2 encodes a RhoGAP protein with growth suppressor function and is underexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10824–10830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208310200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin ME, Avner MR, Huh CG, Yuan BZ, Thorgeirsson SS, Popescu NC. DLC-1, a Rho GTPase-activating protein with tumor suppressor function, is essential for embryonic development. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:1191–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin ME, Ullmannova V, Guan M, Popescu NC. Deleted in liver cancer 3 (DLC-3), a novel Rho GTPase-activating protein, is downregulated in cancer and inhibits tumor cell growth. Oncogene. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin ME, Yuan BZ, Thorgeirsson SS, Popescu NC. Gene structure, tissue expression, and linkage mapping of the mouse DLC-1 gene (Arhgap7) Gene. 2002;288:119–127. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)00462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodison S, Yuan J, Sloan D, Kim R, Li C, Popescu NC, Urquidi V. The RhoGAP protein DLC-1 functions as a metastasis suppressor in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6042–6053. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan M, Zhou X, Soulitzis N, Spandidos DA, Popescu NC. Aberrant methylation and deacetylation of deleted in liver cancer-1 gene in prostate cancer: potential clinical applications. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1412–1419. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hers I, Wherlock M, Homma Y, Yagisawa H, Tavare JM. Identification of p122RhoGAP (deleted in liver cancer-1) Serine 322 as a substrate for protein kinase B and ribosomal S6 kinase in insulin-stimulated cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4762–4770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma Y, Emori Y. A dual functional signal mediator showing RhoGAP and phospholipase C-delta stimulating activities. Embo J. 1995;14:286–291. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer LM, Aravind L, Koonin EV. Common origin of four diverse families of large eukaryotic DNA viruses. J Virol. 2001;75:11720–11734. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.23.11720-11734.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TY, Jong HS, Song SH, Dimtchev A, Jeong SJ, Lee JW, Kim NK, Jung M, Bang YJ. Transcriptional silencing of the DLC-1 tumor suppressor gene by epigenetic mechanism in gastric cancer cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:3943–3951. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TY, Lee JW, Kim HP, Jong HS, Kim TY, Jung M, Bang YJ. DLC-1, a GTPase-activating protein for Rho, is associated with cell proliferation, morphology, and migration in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;355:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung TH, Ching YP, Yam JW, Wong CM, Yau TO, Jin DY, Ng IO. Deleted in liver cancer 2 (DLC2) suppresses cell transformation by means of inhibition of RhoA activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15207–15212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504501102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao YC, Si L, Devere White RW, Lo SH. The phosphotyrosine-independent interaction of DLC-1 and the SH2 domain of cten regulates focal adhesion localization and growth suppression activity of DLC-1. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:43–49. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng DC, Chan SF, Kok KH, Yam JW, Ching YP, Ng IO, Jin DY. Mitochondrial targeting of growth suppressor protein DLC2 through the START domain. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng IO, Liang ZD, Cao L, Lee TK. DLC-1 is deleted in primary hepatocellular carcinoma and exerts inhibitory effects on the proliferation of hepatoma cell lines with deleted DLC-1. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6581–6584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaumann M, Seitz S, Frege R, Estevez-Schwarz L, Scherneck S. Analysis of DLC-1 expression in human breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2003;129:349–354. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0440-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao F, Bowie JU. The many faces of SAM. Sci STKE. 2005 doi: 10.1126/stke.2862005re7. 2005:re7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekimata M, Kabuyama Y, Emori Y, Homma Y. Morphological changes and detachment of adherent cells induced by p122, a GTPase-activating protein for Rho. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17757–17762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seng TJ, Low JS, Li H, Cui Y, Goh HK, Wong ML, Srivastava G, Sidransky D, Califano J, Steenbergen RD, Rha SY, Tan J, Hsieh WS, Ambinder RF, Lin X, Chan AT, Tao Q. The major 8p22 tumor suppressor DLC1 is frequently silenced by methylation in both endemic and sporadic nasopharyngeal, esophageal, and cervical carcinomas, and inhibits tumor cell colony formation. Oncogene. 2007;26:934–944. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song YF, Xu R, Zhang XH, Chen BB, Chen Q, Chen YM, Xie Y. High frequent promoter hypermethylation of DLC-1 gene in multiple myeloma. J Clin Pathol. 2006 doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.031377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullmannova V, Popescu NC. Expression profile of the tumor suppressor genes DLC-1 and DLC-2 in solid tumors. Int J Oncol. 2006;29:1127–1132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullmannova V, Popescu NC. Inhibition of cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis, reactivation of DLC1, and modulation of other gene expression by dietary flavone in breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Detect Prev. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CM, Lee JM, Ching YP, Jin DY, Ng IO. Genetic and epigenetic alterations of DLC-1 gene in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7646–7651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CM, Yam JW, Ching YP, Yau TO, Leung TH, Jin DY, Ng IO. Rho GTPase-activating protein deleted in liver cancer suppresses cell proliferation and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8861–8868. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam JW, Ko FC, Chan CY, Jin DY, Ng IO. Interaction of deleted in liver cancer 1 with tensin2 in caveolae and implications in tumor suppression. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8367–8372. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaga M, Sekimata M, Fujii M, Kawai K, Kamata H, Hirata H, Homma Y, Yagisawa H. A PLCdelta1-binding protein, p122/RhoGAP, is localized in caveolin-enriched membrane domains and regulates caveolin internalization. Genes Cells. 2004;9:25–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HL, Janmey PA. Phosphoinositide regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:761–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan BZ, Durkin ME, Popescu NC. Promoter hypermethylation of DLC-1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene, in several common human cancers. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2003a;140:113–117. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00674-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan BZ, Jefferson AM, Baldwin KT, Thorgeirsson SS, Popescu NC, Reynolds SH. DLC-1 operates as a tumor suppressor gene in human non-small cell lung carcinomas. Oncogene. 2004;23:1405–1411. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan BZ, Miller MJ, Keck CL, Zimonjic DB, Thorgeirsson SS, Popescu NC. Cloning, characterization, and chromosomal localization of a gene frequently deleted in human liver cancer (DLC-1) homologous to rat RhoGAP. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2196–2199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan BZ, Zhou X, Durkin ME, Zimonjic DB, Gumundsdottir K, Eyfjord JE, Thorgeirsson SS, Popescu NC. DLC-1 gene inhibits human breast cancer cell growth and in vivo tumorigenicity. Oncogene. 2003b;22:445–450. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Thorgeirsson SS, Popescu NC. Restoration of DLC-1 gene expression induces apoptosis and inhibits both cell growth and tumorigenicity in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:1308–1313. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]