Abstract

The Ca2+ ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum has a prominent role in excitation/contraction coupling of cardiac muscle, as it induces relaxation by sequestering Ca2+ from the cytoplasm. The stored Ca2+ is in turn released to trigger contraction. We review here experiments demonstrating that in cardiac myocytes Ca2+ signaling and contractile activation are strongly altered by pharmacological inhibiton or transcriptional downregulation of SERCA. On the other hand, kinetics and intensity of Ca2+ signaling are improved by SERCA overexpression following delivery of exogenous cDNA by adenovirus vectors. Experiments on adrenergic hypertrophy demonstrate SERCA downregulation, consistent with its pathogenetic involvement in cardiac hypertrophy and failure, as also shown in other experimental models and clinical studies. Compensation by alternate Ca2+ signaling proteins, including functional activation and increased expression of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and TrpC proteins has been observed. These compensatory mechanisms, including calcineurin activation, remain to be clarified and are a most important subject of current studies.

Keywords: Ca2+ transport, sarcoplasmic reticulum, Ca2+ signaling in cardiac muscle, excitation-contraction coupling, adrenergic hypertrophy, SERCA as a pathogenetic factor in cardiac diseases

On occasion of Professor Ebashi’s visit to the Cardiovascular Research Institute of the University of California in San Francisco, the earliest preparations of vesicular fragments of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) were obtained under his guidance (1). A warm memory remains with us of Professor Ebashi’s influence and guidance through many hours in the laboratory, continuing at the end of day with stimulating and inspiring discussions at dinner in various San Francisco restaurants. At that time, SR membrane vesicles were referred to as “Relaxing Factor” since they prevented “superprecipitation” (i.e., contraction analog) of native actomyosin (containing myosin, actin and the troponin complex) upon addition of ATP. It was soon established that this effect was produced by ATP dependent sequestration of Ca2+ by the vesicles from the reaction medium. In fact, the same relaxing effect could be produced simply by Ca2+ chelation with EGTA added to the medium. The functional behavior of isolated cardiac SR vesicle in vitro turned out to be similar to that exhibited by SR vesicles isolated from skeletal muscle (2, 3), due to the Ca2+ activated Sarco-Endoplasmic Reticulum ATPase (SERCA) which is a prominent protein component of both preparations. The catalytic and transport cycle of SERCA includes ATP utilization by formation of a phosphorylated enzyme intermediate, translocation of bound Ca2+ across the SR membrane against a concentration gradient, and final hydrolytic cleavage of Pi from the phosphoenzyme intermediate (4). We review here information presently available on the role of SERCA in physiology and diseases of heart muscle, discovered by several laboratories working in the field, and illustrated by experimental results obtained in our own laboratory.

SERCA and Ca2+ signaling in cardiac muscle

The cardiac SR ATPase (SERCA2a) is encoded by the (human nomenclature) ATP2A2 gene, which also yields the SERCA2b isoform found in the endoplasmic reticulum of most cells (5, 6). It is by now well established that SERCA2 plays an important role in relaxation of heart muscle, as it sequesters cytosolic Ca2+ by active transport into intracellular stores delimited by the SR membranes. The stored Ca2+ is in turn released into the cytoplasm upon membrane excitation to induce contraction. This can be convincingly demonstrated on primary cultures of cardiac myocytes, as they provide a rather simple system to study complementary features of SERCA transport activity and cytosolic Ca2+ signaling.

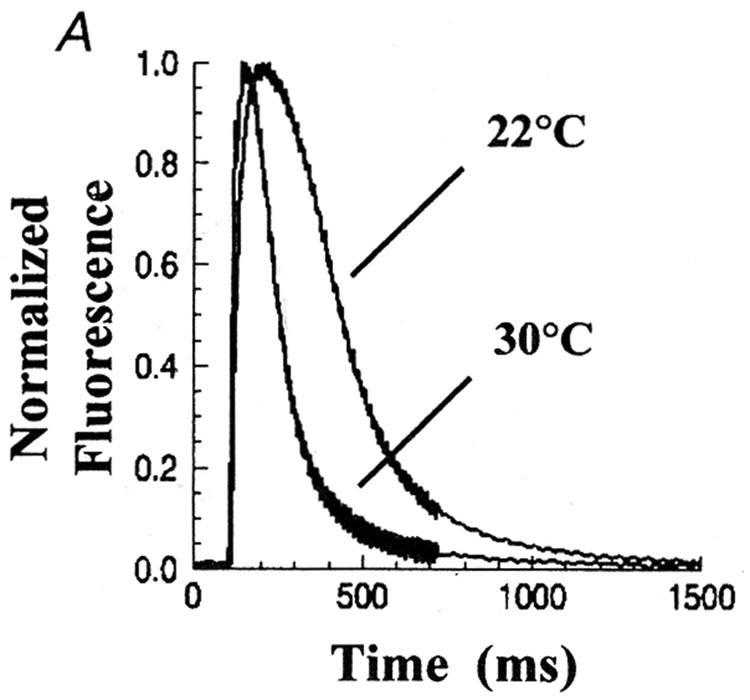

The cytosolic Ca2+ signaling transients observed in myocytes subjected to electric stimuli include a rapid rise followed by a slower decay (Fig 1). The rapid Ca2+ rise does not show significant dependence on temperature, as expected of passive flux through a channel. On the contrary, the rate of decay exhibits strong temperature dependence, similar to that exhibited by the transport activity of isolated SR vesicles (Fig 1). This parallel behavior is consistent with dependence of the decay phase of Ca2+ transients on active transport by the SERCA enzyme (7).

Fig 1. Temperature dependence of cytosolic Ca2+ transients and active Ca2+ transport by cardiac SR vesicles.

The Ca2+ transients were recorded using a fluorescence indicator in cultured neonatal rat myocytes (A). ATP dependent Ca2+ active transport (B) was measured with homogenized myocytes using radioactive tracer (7).

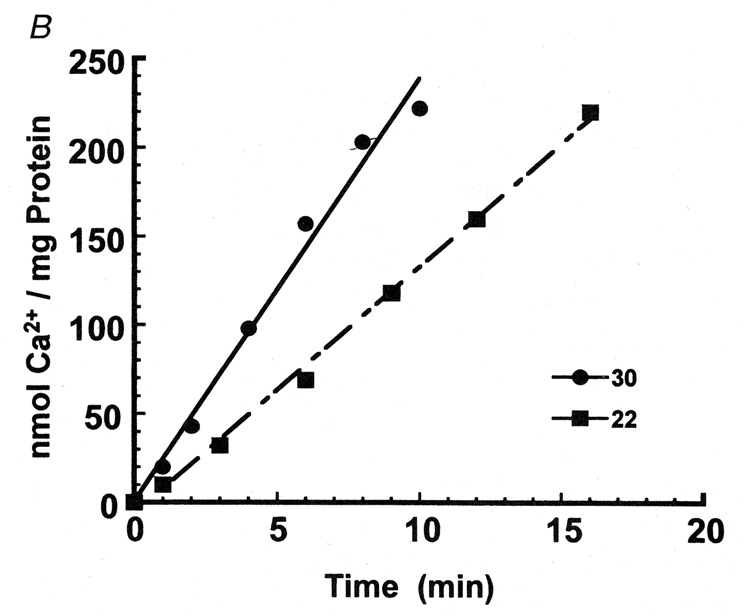

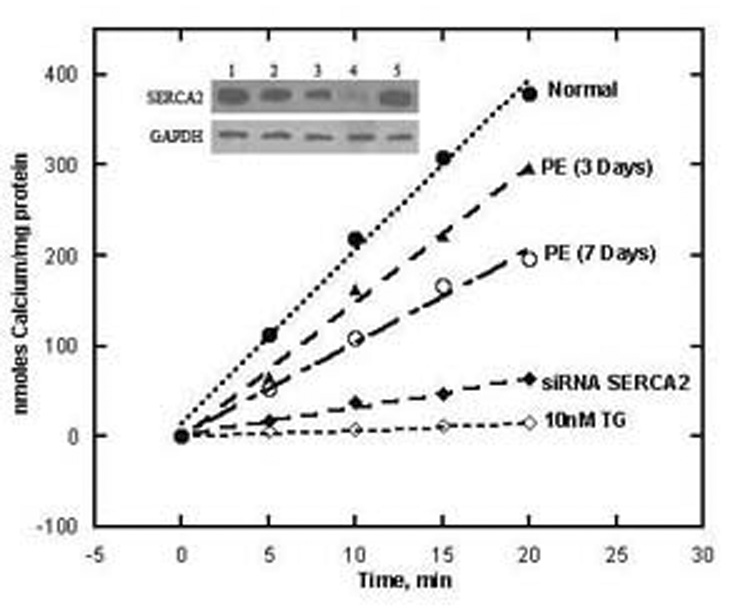

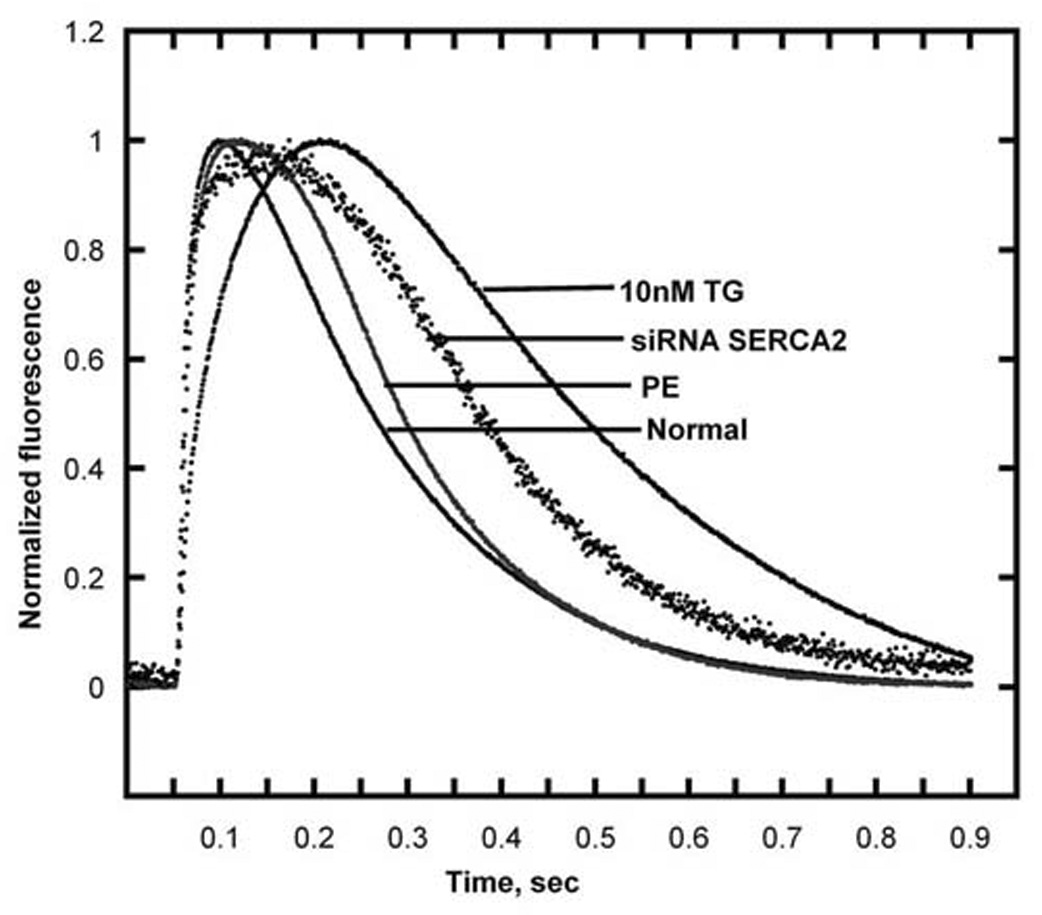

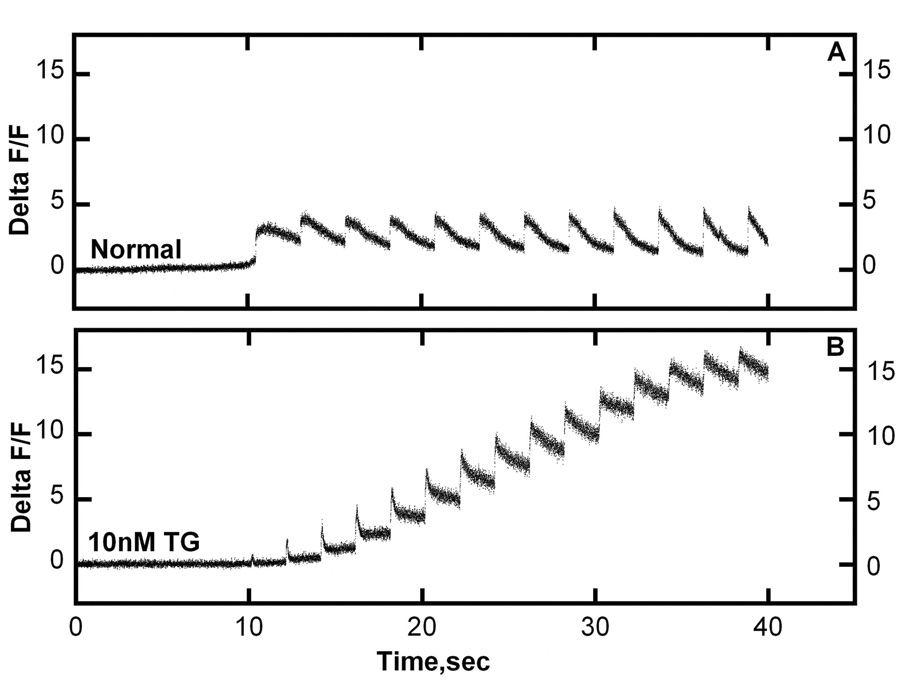

The dependence of cytosolic Ca2+ signaling on transport by SERCA can be demonstrated directly by inhibiting its catalytic and transport activity (8) with thapsigargin (TG), a plant derived sesquiterpene lactone. Specific inhibition of SERCA is obtained in situ by exposing cardiac myocytes to nanomolar concencentrations of TG in the culture medium (Fig 2). Such low concentrations of TG inhibit specifically SERCA activity, without apparent effects on cell growth or other cell characteristics (9). An alternative experimental approach is downregulation of SERCA expression by the use of short interfering RNA (10), with consequent reduction of overall transport activity (Fig 2). Additional evidence is obtained in myocytes subjected to adrenergic hypertrophy (9), as significant reduction of SERCA expression is produced relative to general protein expression. In all cases, reduction of Ca2+ transport activity, due to either SERCA inhibition or down regulation, results in pronounced alterations of cytosolic transients and marked slowing of the decay phase (Fig 3). It is of interest that SERCA inhibition with TG in myocytes, is followed by compensatory increase in Na+/Ca2+ exchange activity (Fig 4), as a compensatory mechanism to eliminate cytosolic Ca2+ through the plasma membrane. In fact, if Na+/Ca2+ exchange is prevented by placing the myocytes in Na+ free medium, the basal (“diastolic”) level of cytosolic Ca2+, between consecutive stimuli, is progressively increased (Fig 4).

Fig 2. Protein levels and ATP dependent Ca2+ transport in homogenates of myocytes exposed to 20 µM PE, siSERCA2 or 10 nM TG.

Control myocytes (1) are compared to myocytes exposed to PE for three (2) or seven days (3), or siSERCA2 for three days (4), or 10 nM TG (5) for three days. Protein levels were measured by Western blotting and compared to the levels of GAPDH protein. ATP dependent calcium transport was measured using homogenates of cultured cardiac myocytes, harvested after 3 or 7 days of treatment as specified above (9).

Fig 3. Alteration of Ca2+ signaling kinetics in myocytes exposed to PE, SERCA2 short interfering RNA or TG.

The myocytes were exposed to 20 µM PE for seven days, or to siSERCA2 for three days, or to 10 nM TG for three days. Cytosolic Ca2+ transients were measured in single cells using fluo-4. The cells were subjected to field stimulation (1 Hz pulsing). Each trace represents the average of transients obtained from 30 to 70 cells over 5 different preparations. The fluorescence signal was normalized to the maximal change per each transient (9).

Fig 4. Compensatory increase in Na+ /Ca2+ exchange activity following SERCA inhibition by TG in cardiac myocytes.

Control myocytes (upper panel) and myocytes exposed to 10 nM TG for three days (lower Panel) were subjected to a series of voltage clamp depolarizations to −10 mv at 2 sec intervals. Ca2+ transients were then measured in Na+ free bathing solution, thereby eliminating Na+ /Ca2+ exchange. It is clear that, in the absence of Na+/Ca2+ exchange, the myocytes with inhibited SERCA show a progressive increase of the basal cytosolic Ca2+ level as a consequence of consecutive stimuli (9).

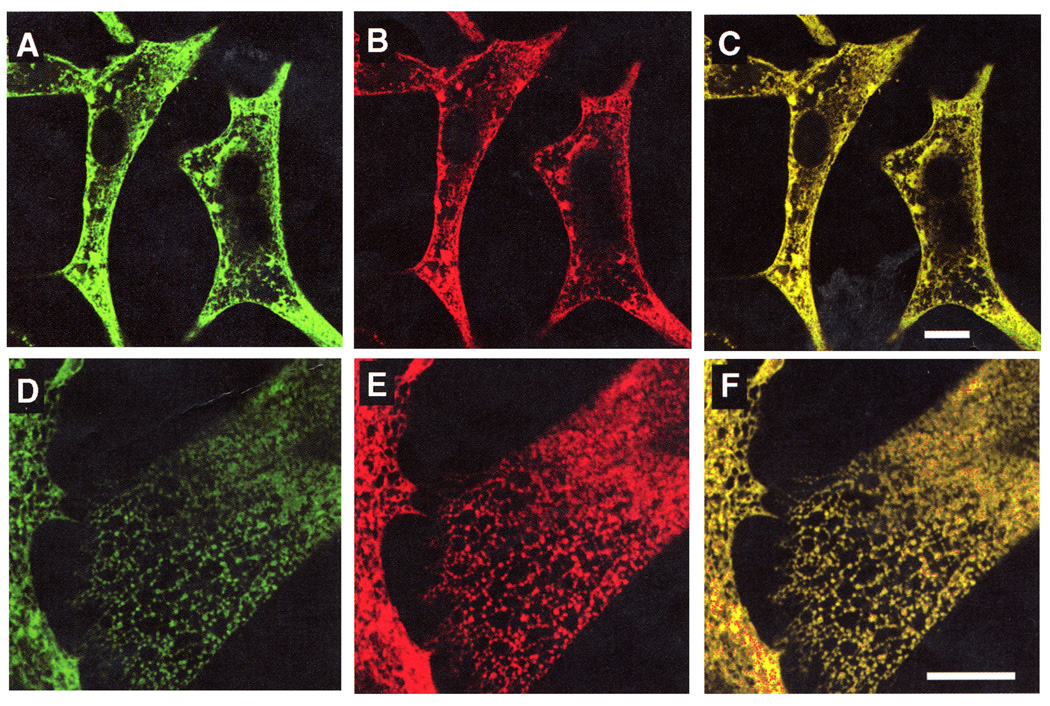

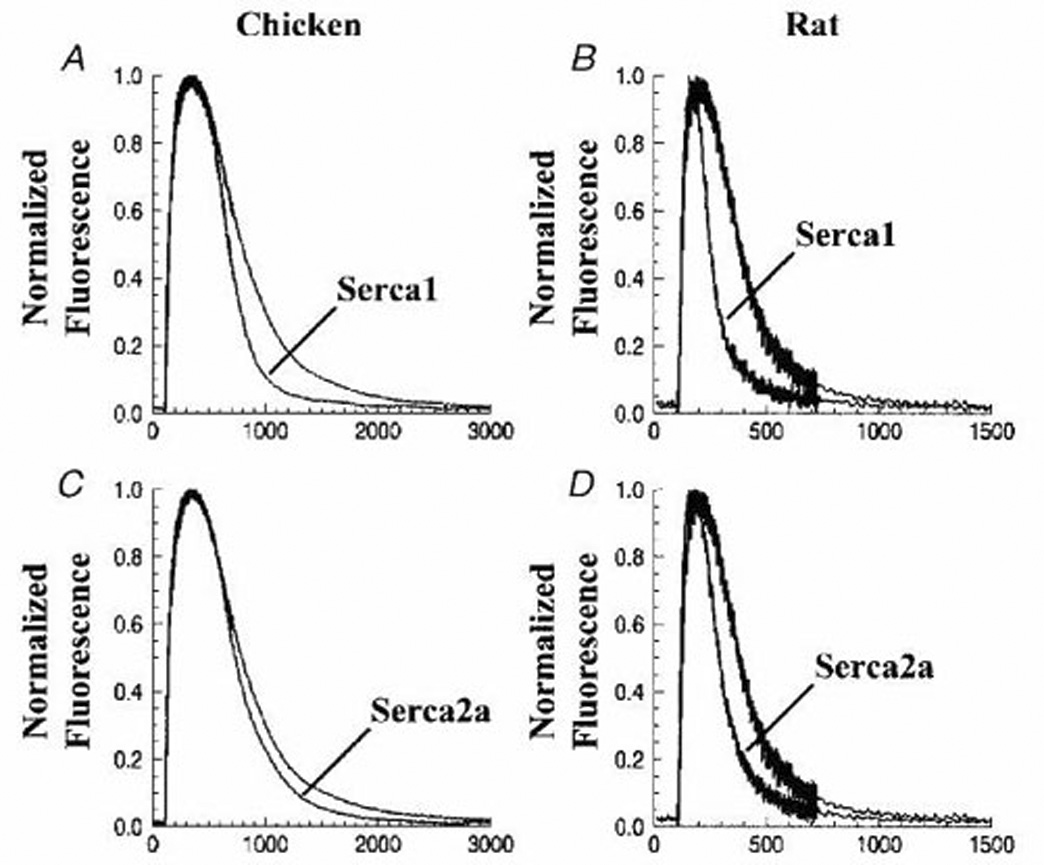

As a further demonstration of SERCA involvements in Ca2+ transient kinetics, faster decay of the transients can be obtained by SERCA overexpression, encoded by exogenous cDNA. For this purpose, we have used adenoviral vectors for efficient introduction of exogenous SERCA cDNA in cardiac myocytes, under control of constitutive or cardiac cell specific promoters (11). Most importantly, it can be shown by the use of diverse SERCA isoforms and specific antibodies (12), that the protein encoded by the exogenous cDNA is targeted exactly to the same membrane location as the protein encoded by the endogenous gene (Fig 5). In all cases, the resulting effect on Ca2+ transients is a shorter decay phase, as expected from a faster Ca2+ removal from the cytoplasm (Fig 6).

Fig 5. Intracellular targeting of SERCA1 gene product following delivery of exogenous cDNA by means of adenovirus vector under control of cardiac cell specific promoter.

Colocalization of exogenous SERCA1 with endogenous SERCA2 is demonstrated by specific immunostaining for endogenous SERCA2 (A and D), exogenous SERCA 1 (B and E), and combined staining forn SERCA2 and SERCA1 (C and F). Scale bars correspond to 10 µm (12).

Fig 6. Ca2+ signaling transients in control cardiac myocytes, and following overexpression of exogenous SERCA.

Cytosolic Ca2+ transients were measured in chicken embryo or neonatal rat myocytes using fluo-4. Myocytes overexpressing exogenous SERCA1 or SERCA2 (following infection with adenovirus vectors) are compared with control myocytes. The cells were subjected to field stimulation (1 Hz pulsing). Each trace represents the average of transients obtained from 15–30 cells over 3–5 different preparations. The fluorescence signal was normalized to the maximal change per each transient (12).

Physiologic and pathogenetic role of SERCA in excitation-contraction coupling

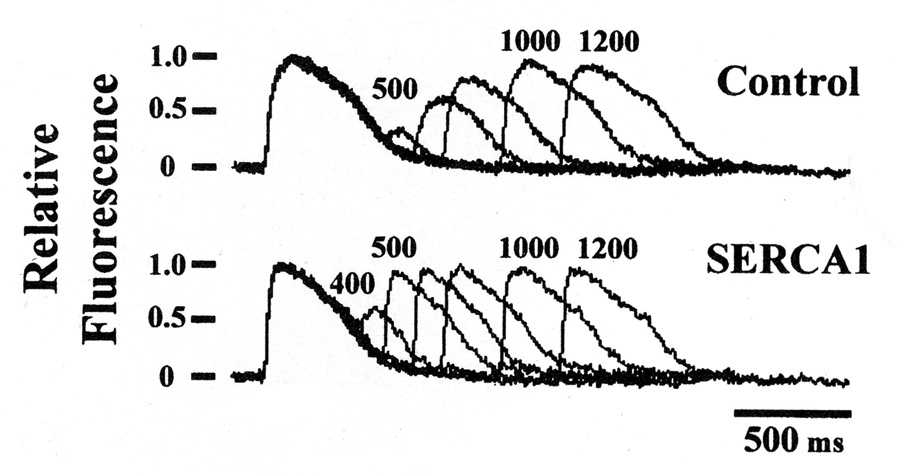

An intriguing question is whether, in addition to kinetic effects, the maximal level of Ca2+ stored within the lumen of the SR is affected by changes in overall SERCA activity. Assuming the same internal volume delimited by the SR membrane, the maximal Ca2+ concentration that can be possibly reached in the lumen of SR depends on Ca2+ dissociation constant from the ATPase inward oriented Ca2+ binding sites following utilization of ATP. In principle, this limit is independent of the overall Ca2+ transport velocity. On the other hand, if the frequency of consecutive Ca2+ release stimuli is increased, the time interval between stimuli becomes a limiting factor, and the overall transport velocity then determines the level of maximal filling. This is in fact observed when myocytes are subjected to trains of stimuli with progressively shorter intervals, whereby the amount of released Ca2+ becomes progressively smaller, as it is limited by the luminal Ca2+ load reached within the short interval. In this case, compensation is obtained by overexpression of exogenous SERCA, as a greater number of SERCA molecules allows a higher overall transport velocity and a more effective filling of the SR lumen within a limited time interval between stimuli (Fig 7).

Fig 7. Ca2+ signaling transients (A) following stimuli at progressively shorter.

intervals in control myocytes and following overexpression of exogenous SERCA. It is shown that the amount of released Ca2+ is reduced (B) as the interval between consecutive stimuli is shorter, indicating a time limit for Ca2+ refilling of SR stores between stimuli. This limit is significantly overcome by overexpression of exogenous SERCA1 (7)

With regard to the relevance of Ca2+ transport to contractile activity, it has been clearly shown that specific inhibition of SERCA by TG in situ, interferes (13) with the contractile response of cardiac myocytes to membrane excitation. This effect is certainly relevant to cardiac pathology. In fact, many experimental and clinical studies indicate that inadequate function of the Ca2+ transport ATPase (SERCA2) and the consequent alterations of cytosolic Ca2+ signaling are pathogenetic features of cardiac hypertrophy and failure (14 – 24). Even expression of SERCA isoforms with higher than normal Ca2+ affinity can lead to cardiac hypertrophy and failure (25).

An important feature of SERCA2 is its regulation by phospholamban in cardiac muscle, as originally described by Kirchberger et al. (26) and subsequently studied extensively in several laboratories, especially by E.G. Kranias (27). Phospholamban is a small protein that interacts with the transmembrane and stalk regions of the SERCA protein. The functional effect resulting from this interaction is a displacement of the ATPase activation curve to a higher Ca2+ concentrations range, therefore yielding lower activity at relevant cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations (28). This effect is overcome by phospholamban phosphorylation following adrenergic activation of protein kinase, thereby providing an elegant explanation for the increased cardiac contraction upon sympathetic discharge. Numerous and elegant studies with transgenic animals have shown convincingly that phospholamban is a key determinant of cardiac function and dysfunction (29). In addition, specific mutations in the human phospholamban gene may result in severe cardiomyopathies (30).

The evidence indicating that deficiencies of SERCA2 expression, function and regulation may be a significant factor in the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy and failure ( 14 – 24), has led to attempts to relieve related shortcomings by over-expression through introduction of exogenous SERCA cDNA (31 – 37). On the other hand, it is now becoming apparent that regulation of endogenous expression is an important factor to be considered. In the experimental setting, it is clear that myocytes undergoing adrenergic hypertrophy (38) under-express SERCA, as the enzyme does not seem to be included in the hypertrophy transcriptional program (9). In addition, alterations of cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis trigger over-expression of other Ca2+ handing proteins such as Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and the TRPC proteins (10). Calcineurin, a Ca2+ /calmodulin activated phosphatase and transciptiona activator (39, 40) that plays an important role in heart development and remodeling (41, 42), is likely to be involved in adaptive responses to alterations of cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis (43 – 45). However, the consequences of its activation are likely to be interwoven with additional mechanisms of transcriptional regulation (46) that may enhance or counteract the overall effect, directing it to expression of specific proteins, and excluding others. Presently, clarification of adaptive mechanisms for up- and down-regulation of endogenous SERCA and other Ca2+ handling proteins is a most promising endeavor in order to gain understanding and hopefully improving treatment of cardiac hypertrophy and failure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Continuous support by the National Institutes of Health (Heart, Blood and Lung Institute) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Inesi G, Ebashi S, Watanabe S. Preparation of vesicular relaxing factor from bovine heart muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 1964;207:1339–1344. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1964.207.6.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebashi S, Lipmann F. Adenosine-triphosphate linked concentration of calcium ions in a particulate fraction of rabbit muscle. J. Cellular Biol. 1962;14:389–400. doi: 10.1083/jcb.14.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasselbach W, Makinose M. ATP and active transport. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1962;7:132–136. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(62)90161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inesi G G, Sumbilla C, Kirtley ME. Relationships of molecular structure and function in Ca2+-transport ATPase. Physiological Reviews. 1990;70:749–760. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.3.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lytton J, Zarain-Herzberg A, Periasamy M, MacLennan DH. Molecular cloning of the mammalian smooth muscle sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:7059–7065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zarain-Herzberg A, MacLennan DH DH, Periasamy M. Characterization of rabbit cardiac sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase gene. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4670–4677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavagna M, O'Donnell JM, Sumbilla C, Inesi G, Klein MG. Exogenous Ca2+-ATPase isoform effects on Ca2+ transients of embryonic chicken and neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. J Physiol. 2000;528:53–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00053.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sagara Y, Inesi G. Inhibition of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transport ATPase by thapsigargin at subnanomolar concentrations. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:13503–13506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prasad AM, Ma H, Sumbilla C, Lee DI, Klein MG, Inesi G. Phenylephrine hypertrophy, Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA2), and Ca2+ signaling in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C2269–C2275. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00441.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seth M, Sumbilla C, Mullen SP, Lewis D, Klein MG, Hussain A, Soboloff J, Gill DL, Inesi G. Sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA) gene silencing and remodeling of the Ca2+ signaling mechanism in cardiac myocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:16683–16688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407537101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inesi G, Lewis D, Sumbilla C, Nandi A, Strock C, Huff KW, Rogers TB TB, Johns DC, Kessler PD, Ordahl CP. Cell-specific promoter in adenovirus vector for transgenic expression of SERCA1 ATPase in cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:C645–C653. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.3.C645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma H, Sumbilla C, Farrance IK, Klein MG, Inesi G. Cell-specific expression of SERCA, the exogenous Ca2+ transport ATPase, in cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 2004;286:C556–C564. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00328.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirby MS, Sagara Y, Gaa S, Inesi G, Lederer WJ, Rogers TB. Thapsigargin inhibits contraction and Ca2+ transient in cardiac cells by specific inhibition of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pump. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:12545–12551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chien KR. Meeting Koch's postulates for calcium signaling in cardiac hypertrophy. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105:1339–1342. doi: 10.1172/JCI10079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bers DM, Eisner DA, Valdivia HH. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ and heart failure: roles of diastolic leak and Ca2+ transport. Circ. Res. 2003;93:487–490. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000091871.54907.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng M, Dilly K, Dos Santos CJ, Li M, Gu Y, Ursitti JA, Chen J, Ross J, Jr, Chien KR, Lederer JW, Wang Y Y. Sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium defect in Ras-induced hypertrophic cardiomyopathy heart. Am. J. Physiol. 2004;286:H424–H433. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00110.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schultz JJ, Glascock BJ, Witt SASA, Nieman ML, Nattamai KJ, Liu LH, Lorenz JN, Shull GE, Kimball TR, Periasamy M. Accelerated onset of heart failure in mice during pressure overload with chronically decreased SERCA2 calcium pump activity. Am. J. Physiol. 2004;286:H1146–H1153. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00720.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okayama H, Hamada M, Kawakami H, Ikeda S, Hashida H, Shigematsu Y, Hiwada K. Alterations in expression of sarcoplasmic reticulum gene in Dahl rats during the transition from compensatory myocardial hypertrophy to heart failure. J. Hypertens. 1997;15:1767–1774. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715120-00087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arai M, Alpert NR, MacLennan DH, Barton P, Periasami M. Alterations in sarcoplasmic reticulum gene expression in human heart failure. A possible mechanism for alterations in systolic and diastolic properties of the failing myocardium. Circ. Res. 1993;72:463–469. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasenfuss G, Meyer M, Schillinger W, Preuss M, Pieske B, Just H. Calcium handling proteins in the failing human heart. Basic Res. Cardiol. 1997;92 Suppl 1:87–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00794072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasenfuss G, Reinecke H, Studer R, Meyer M, Pieske B, Holtz J, Holubarsch C, Posival H, Just H, Drexler H. Relation between myocardial function and expression of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase in failing and nonfailing human myocardium. Circ. Res. 1994;75:434–442. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer M, Schillinger W, Pieske B, Holubarsch C, Heilmann C, Posival H, Kuwajima G, Mikoshiba K, Just H, Hesenfuss G. Alterations of sarcoplasmic reticulum proteins in failing human dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1995;92:778–784. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehnart SH, Schillinger W, Pieske B, Prestle J, Just H, Hasenfuss G. Sarcoplasmic reticulum proteins in heart failure. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;853:220–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MercadierJ JJ, Lompre AM, Duc P, Boheler KR, Fraysse JB, Wisnewsky C, Allen PD, Komajda M, Schwartz K. Altered sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase gene expression in the human ventricle during end-stage heart failure. J. Clin. Invest. 1990;85:305–309. doi: 10.1172/JCI114429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vangheluwe P, Tjwa M, Van Den Bergh A, Louch WE, Beullens M, Dode L, Carmeliet P, Kranias E, Herijgers P, Sipido KR, Raeymaekers L, Wuytack F. A SERCA2 pump with an increased Ca2+ affinity can lead to severe cardiac hypertrophy, stress intolerance and reduced life span. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2006;41:308–317. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirchberger MA, Tada M, Katz AM. Phospholamban: a regulatory protein of the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Recent Adv. Stud. Cardiac Struct Metab. 1975;5:103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLennan DH, Kranias EG. Phospholamban: a crucial regulator of cardiac contractility. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4:566–577. doi: 10.1038/nrm1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cantilina T, Sagara Y, Inesi G, Jones LR. Comparative studies of cardiac and skeletal sarcoplasmic reticulum ATPases, Effect of a phospholamban antibody on enzyme activation by Ca2+ J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:17018–17025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez P, Kranias EG. Phospholamban: a key determinant of cardiac function and dysfunction. Arch. Mal. Coeur Vaiss. 2005;98:1239–1243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haghighi K, Kolokathis K, Gramolini AO, Waggoner JR, Pater L, Lynch RA, Fan GC, Tsiapras D, Parekh RR, Dorn GW, 2nd, MacLennan DH, Kremastinos DT, Kranias EG. A mutation in the human phospholamban gene, deleting arginine 14, results in lethal, hereditary cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006;103:1388–1393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510519103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Del Monte F, Hajjar RJ. Targeting calcium cycling proteins in heart failure through gene transfer. J. Physiol. 2003;546:49–61. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Del Monte F, Williams E, Lebeche D, Schmidt U, Rosenzweig A, Gwathmey JK, Lewandowski ED, Hajjar RJ. Improvement in survival and cardiac metabolism after gene transfer of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in a rat model of heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:1424–1429. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.095574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flesch M, Schwinger RH, Schnabel P, Schiffer F, van Gelder I, Bavendiek U, Sudkamp M, Kuhn-Regnier F, Bohm M. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase and phospholamban mRNA and protein levels in end stage heart failure due to ischemic or dilated cardiomyopathy. J Mol. Med. 1996;74:321–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00207509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giordano FJ, He H, McDonough P, Meyer M, Sayen MR, Dillmann WH. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer reconstitutes depressed sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase levels and shortens prolonged cardiac myocyte Ca2+ transients. Circulation. 1997;96:400–403. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.2.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He H, Giordano FJ, Hilal-Dandan R, Choi DJ, Rockman HA, McDonough PM, Bluhm WF, Meyer M, Sayen MR, Swanson E, Dillmann WH. Overexpression of the rat sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase gene in the heart of transgenic mice accelerates calcium transients and cardiac relaxation. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:380–389. doi: 10.1172/JCI119544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loukianov E, Ji Y, Grupp IL, Kirkpatrick DL, Baker DL, Loukianova T, Grupp G, Lytton J, Walsh RA, Periasamy M. Enhanced myocardial contractility and increased Ca2+ transport function in transgenic hearts expressing the fast-twitch skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Circ. Res. 1998;83:889–897. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.9.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyamoto MI, del Monte F, Schmidt U, DiSalvo TS, Kang ZB, Matsui T, Guerrero JL, Gwathmey JK, Rosenzweig A, Hajjar RJ. Adenoviral gene transfer of SERCA2a improves left-ventricular function in aortic-banded rats in transition to heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:793–798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simpson P, McGrath A, Savion S. Myocyte hypertrophy in neonatal rat heart cultures and its regulation by serum and by catecholamines. Circ. Res. 1982;51:787–801. doi: 10.1161/01.res.51.6.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klee CB, Ren H, Wang X. Regulation of the calmodulin-stimulated protein phosphatase, calcineurin. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:13367–13370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crabtree GR. Calcium, calcineurin, and the control of transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:2313–2316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams RS, Rosenberg P. Calcium-dependent Gene Regulation in Myocytes hypertrophy and Remodeling. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 2002;67:339–345. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2002.67.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilkins BJ, Molkentin JD. Calcineurin and cardiac hypertrophy: where have we been? Where are we going? J. Physiol. 2002;541:1–8. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Munch G, Bolck B, Karczewski P, Schwinger RH. Evidence for calcineurin-mediated regulation of SERCA 2a activity in human myocardium. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2002;34:321–334. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brittsan AG, Ginsburg KS, Chu G, Yatani A, Wolska BM, Schmidt AG, Asahi M, MacLennan DH, Bers DM, Kranias EG, Chronic SR. Ca2+-ATPase inhibition causes adaptive changes in cellular Ca2+ transport. (Increased L-type Ca2+ current (ICa) density) Circ. Res. 2003;92:769–776. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000066661.49920.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bush EW, Hood DB, Papst PJ, Chapo JA, Minobe W, Bristow MR, Olson EN, McKinsey TA. Canonical transient receptor potential channels promote cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through activation of calcineurin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:33487–33496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abbasi S, Lee JD, Su B, Chen X, Alcon JL, Yang J, Kellems RE, Xia Y. Protein kinase-mediated regulation of calcineurin through the phosphorylation of modulatory calcineurin-interacting protein 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:7717–7726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510775200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]