Abstract

The incidence of intraoperative femoral fractures with a single design of stem implant, the Meridian (Stryker-Howmedica, Rutherford, N.J.), has been assessed in a study of 117 implants in patients treated consecutively between 1996 and 2001. The aim of the study was to evaluate the risk factors for suffering an intraoperative fracture and to determine, based on a short-term follow-up, if there were radiographic signs of early loosening. The following variables were analysed: demographic factors of the patient, morphology of the femur, intraoperative factors and postoperative radiographic factors. The radiographic stability of the implant and the presence of early signs of loosening were evaluated 2 years after surgery. The incidence of femoral fractures was 11% (13 cases in 117 implants), which is higher that reported in earlier published studies, and there was an increased number of fractures when the proximal filling of the femoral canal was higher. Although there was no statistically significant relation between the variables studied and the appearance of an intraoperative fracture, we conclude that the appearance of a femoral intraoperative fracture did not affect the radiographic stability of the implant during the short-term follow-up of our study cohort.

Résumé

L’incidence des fractures peropératoires a été évaluée chez des patients traités par l’implant Méridian (Stryker - Howmedica, Rutherford, NJ). Nous avons étudié une série consécutive de 117 implants réalisée entre 1996 et 2001. Nous avons également essayé de déterminer quels étaient les facteurs de risque de fractures peropératoires et essayé de visualiser les signes précoces de descellement sur un suivi relativement court. Les éléments suivants ont été pris en compte : facteur démographique du patient, morphologie du fémur, facteur peropératoire et radiographies post opératoires. La stabilité radiographique de l’implant et la présence de signes précoces de descellement ont été évalués deux ans après l’intervention. L’incidence des fractures peropératoires du fémur a été de 11% (13 cas sur 117), plus importantes que dans d’autres séries publiées. Le taux de fracture a été plus important lorsque les contacts entre la pièce fémorale et le canal fémoral ont été très élevés. Il n’y a pas de relation significative entre les facteurs étudiés et l’apparition, entre ces différents facteurs, d’une fracture peropératoire. Quoiqu’il en soit, l’existence d’une fracture peropératoire n’entraîne pas d’instabilité radiographique de l’implant au suivi à court terme.

Introduction

Intraoperative hip fractures have been reported to be a complication of total hip arthroplasty (THA), with the incidence of fractures ranging from 0.4 [21] to 1.8% [24] in cemented THA. In uncemented arthroplasty, with “fit and fill” techniques, the effort by surgeons to obtain a press fit in the femoral component has been found to increase the incidence of intraoperative fracture, with several studies reporting fracture incidences of between 3 and 13% [1, 8, 9, 13, 15, 17, 25]. The incidence of intraoperative fractures in revision surgery is even higher, especially in the presence of poor bone stock [16, 19]. In some studies, the appearance of a fracture in the proximal femur did not affect the outcome of the arthroplasty [8, 9, 14, 17, 20, 22], while the results of other studies suggest worse results and a higher loosening rate after a fracture when the latter appeared around the tip of the stem, thereby compromising its stability [4, 12, 15].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the incidence of intraoperative femoral fracture with the Meridian stem implant (Stryker-Howmedica, Rutherford, N.J.) in terms of identifying the risk factors for suffering an intraoperative fracture and determining the effect of these fractures on the short-term stability of the implant.

Materials and methods

Patients

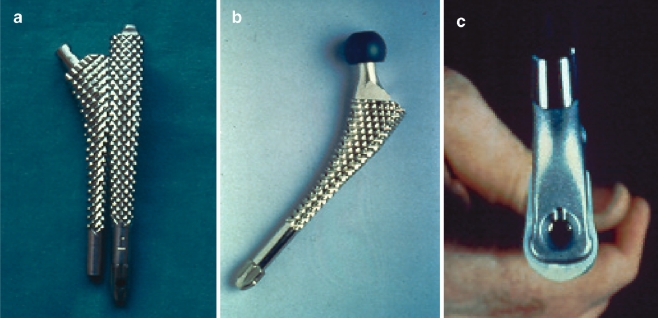

Between May 1996 and February 2001 117 consecutive uncemented total hip arthroplasties were performed at our institution using the same design of implant (Meridian; Stryker-Howmedica, Rutherford, N.J.; Fig. 1), which is a proximally coated femoral stem without a collar. The acetabular component was the same design in all cases (Vitalock; Stryker-Howmedica).

Fig. 1.

a The front and side view of one of the broaches employed for preparing the canal prior to the insertion of the stem, b the trial reduction was always made with the last broach used, c the cross section of the Meridian stem

The underlying diagnoses were: primary osteoarthritis in 72 cases, avascular necrosis of the femoral head in 18 cases, rheumatoid arthritis in six cases, hip dysplasia in seven cases, post-traumatic arthritis in seven cases, ankylosing spondylitis in two cases, Legg-Calve-Perthes disease (LCP) sequellae in two hips, one case of ancient hip tuberculosis, one hip protrusion and one conversion of hip arthrodesis.

The average age of the patients at the time of the index surgery was 59.8 years (range: 28–77 years). There were 56 men and 49 women, of whom 11 men and 1 woman underwent a bilateral procedure. Fifty-five right hips and 62 left hips were treated. The mean weight of the patients was 74.94 kg (range: 58–104 kg). Of the patients, 33 (28.2%) smoked, and 23 patients (19.7%) consumed alcohol. Four patients were being treated with chronic steroid medication for rheumatoid arthritis.

The preoperative range of motion of the hip was assessed in every patient and was as follows: a mean flexion of 80.8° (range: 0–120°), mean abduction of 17.4° (range: 0–40°), mean adduction of 13.5° (range: 0–40°), mean external rotation of 9° (range: 0–45°), mean internal rotation of 2.4° (range: −20 to 20°). Eleven patients had an average flexion contracture of the hip of 12° (range: 5–20°). The preoperative Harris Hip Score (HHS) [11] was determined in each case.

Surgical technique

Of the procedures carried out, 107 were performed through a lateral approach and the remaining ten artroplasties through a posterolateral approach under spinal anaesthesia. The senior author (E.G-G) performed 47 of the procedures, while 61 were performed by other staff members and the remaining nine hips by residents. The standard reaming and broaching technique used was line to line following manufacturer’s instructions. The median proximal size of the stem was 3 (range: 0–7) and the median distal stem size was 13 (range: 10–17). The femoral head size was 28 mm. The standard neck length was the most frequently used (42 cases), followed by the +4 (36 cases). Fractures were classified following the Mallory classification [14]; each fracture affecting the stability of the stem was managed by cerclage wiring.

Partial weight bearing with crutches was allowed in all cases on the second day after surgery. Patients were discharged from the hospital between the 7th and 12th day, and they continued with partial weight bearing for 6 to 8 weeks following the index procedure.

Radiographic analysis

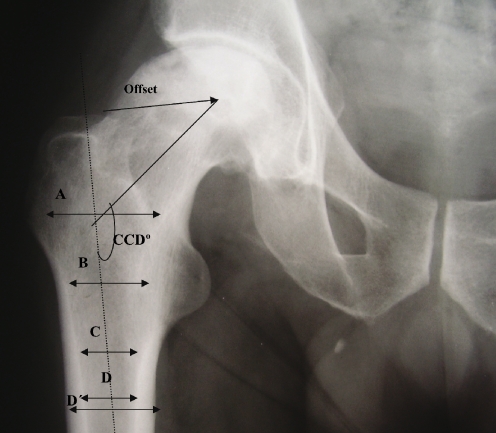

Preoperative AP views of the pelvis taken at 1.1 m and centred in the pubic symphysis (the same procedure as that used for preoperative planning) were evaluated in the study. Proximal femoral osteoporosis was assessed according to the Singh’s classification [23]. We found 33 grade 1 femurs, 25 grade 2, 37 grade 3, 14 grade 4 and 8 grade 5. Cervico-diaphyseal angle, off-set, canal flare index, cortical index and the width of the femoral canal 10 mm proximal to the lesser trochanter, at the lesser trochanter and 10 mm distal to the lesser trochanter as variables for describing the morphology of our femurs were measured in every case (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The different variables measured in the preoperative radiographs to describe the morphology of the femurs. Cervicodiaphyseal angle (CCD), femoral offset and width of the femoral canal proximal to the lesser trochanter (A), at the lesser trochanter (B) and distal to the lesser trochanter (C). A/C Canal flare index, D/D’cortical index

The mean cervico-diaphyseal angle was 134.03° (range: 115–160°), the mean offset was 40.8 mm (range: 21–26 mm) and the mean canal flare index was 2.56. We assessed the cortical thickness of the operated femur as the ratio of the femur diameter to the width of the medullary canal, as described by Engh and Bobyn [6]. The mean cortical index was 0.45. The mean width of the femoral canal proximal to the lesser trochanter, at the lesser trochanter and distal to the lesser trochanter was 45.9, 29.9 and 23.5 mm, respectively.

Postoperative radiographs were used to evaluate the height of the cut of the femur and the orientation of the femoral component. The proximal and distal femoral filling by the stem was calculated by dividing the width of the femoral canal by the width of the prosthesis at that level.

Postoperative radiographs made 2 years after the index procedure were used to evaluate the effect of a femoral fracture in the primary fixation of the implants. Radiolucent lines were categorised according to the zones defined by Gruen et al. [10]. The radiographs were also assessed for the presence of calcar resorption. The fixation of the stems was graded as bone ingrowth, stable fibrous or unstable fibrous, according to the classification of Engh [7].

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed to compare the demographics and the preoperative and postoperative radiographic data of the patients that sustained a femoral fracture with those that did not. Differences in age, weight, preoperative motion, cervico-diaphyseal angle, offset, canal flare index, cortical index scores and the remainder of the quantitative radiographic values in both groups were compared using Student’s t-test. Categorical variables were analysed using the chi-square test of independence or the Fisher exact test. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, Ill.). Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Complications and reoperations

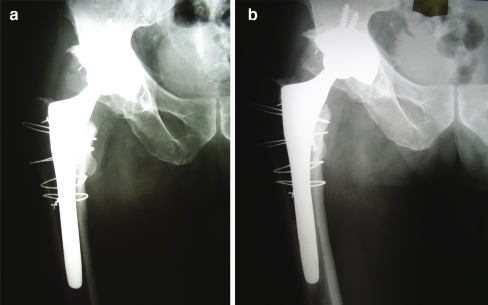

Thirteen patients sustained an intraoperative fracture during the broaching of the femur (three cases) or during the insertion of the stem (ten cases). There were three fractures of the greater trochanter and 11 fractures of the calcar. There were five Mallory type I fractures (two cases did not require wiring), five Mallory type II fractures and one Mallory type III fracture that required four cerclages [14]. All fractures healed uneventfully (Fig. 3). There was no cortical perforation or any fracture of the femoral shaft requiring plating.

Fig. 3.

Fifty-nine-year-old man with a hip arthroplasty for osteoarthritis. a During the broaching of the femur, the patient sustained an intraoperative fracture (Mallory type III) that required four cerclages. b After 2 years of follow-up, the implant is radiographically stable. The patient is asymptomatic and is able to perform all activities of daily living without restrictions

One patient with osteoarthritis suffered an anterior dislocation of the hip, which was treated by closed reduction followed by 3 weeks in bed. There was a single case of deep vein thrombosis. There were no cases of infection or aseptic loosening requiring revision surgery.

Clinical results

The mean modified HHS improved from 48 points (range: 17–76) to a mean of 96 points at the latest follow-up. At the 2-year postoperative evaluation, 100 patients had no pain, 14 had mild pain and three had moderate pain. There were no differences between the group that suffered a fracture and the rest of the patients.

Radiographic analysis

The preoperative, the initial postoperative and the 2-year postoperative radiographs were evaluated by the three authors of the study. The mean height of the cut of the cervical neck was 24.2 mm (range: 8–37 mm). Eighty-five stems had a neutral orientation, 18 were aligned in valgus at a mean of 3° (range: 2–5°) and 13 stems were aligned in slight varus at a mean of 3° (range: 2–5°). The metaphyseal filling of the femoral canal by the stem measured 10 mm proximal to the lesser trochanter was 76% (range: 51–100%), and the diaphyseal filling measured 10 mm distal to the lesser trochanter was 88% (range: 58–100%).

The 2-year postoperative evaluation showed radiolucent lines in 71 femurs. Ninety-two stems were considered to have bone ingrowth, while 25 stems were considered to be stable with fibrous ingrowth; no implant was found to be loose. The calcar has been rounded in 73 femurs and partially resorbed in eight femurs. Table 1 shows the prevalence of radiolucent lines in the different zones.

Table 1.

Results of the fractured group versus the non-fractured group

| Fractured group | Non-fractured group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 13 | 104 | |

| Age | 55.54 | 60.34 | p = 0.19 |

| Weight | 70.4 | 75.46 | p = 0.23 |

| Flexion | 80° | 81° | |

| Extension | 0° | 1.71° | |

| Abduction | 13.75° | 17.94 | |

| Adduction | 13.75° | 13.53° | |

| Internal rotation | 2.27° | 2.41° | |

| External rotation | 5.91° | 9.41° | |

| CCD angle | 135.8° | 133.8° | p = 0.43 |

| Offset | 38 mm | 41.1 mm | p = 0.20 |

| Canal Flare Index | 2.36 | 2.59 | p = 0.12 |

| Cortical Index | 0.46 | 0.45 | p = 0.50 |

| Proximal width | 43.62 mm | 46.24 mm | p = 0.15 |

| Width in calcar | 28.08 mm | 30.05 mm | p = 0.16 |

| Distal width | 21.31 mm | 23.83 mm | p = 0.062 |

| Time | 108.46 min | 111.18 min | p = 0.65 |

| Blood units | 1.92 | 1.62 | p = 0.45 |

| Cut | 26.08 | 24.05 | p = 0.33 |

| Proximal fill | 81.4% | 75.3% | p = 0.057 |

| Distal fill | 88.4% | 88% | p = 0.92 |

Fractured versus non-fractured

The series of patients were divided into two groups according to the presence of an intraoperative fracture. Table 1 summarises the different values for both groups. The results obtained on the patients of this study revealed that there was no association with gender (p = 0.74), weight (p = 0.23), laterality (p = 0.26), tobacco (p = 0.27), alcohol (p = 0.27 or corticosteroids (p = 0.36). In the groups with rheumatoid arthritis (two of six cases), arthrodesis and tuberculosis, the incidence of fracture was higher, but the difference was not statically significant. The grade of osteoporosis was not found to be different according to the score in Singh’s classification (p = 0.32).

No increase in operative time was found in the fracture group (p = 0.65) or in the need for blood units (p = 0.45). Eight of the thirteen fractures appeared in patients operated on by senior surgeons (more than 50 procedures a year), while no fracture occurred in the nine cases performed by residents.

There was a marginal association between a higher femoral fill of the proximal femur and the appearance of an intraoperative fracture. The fractured femurs showed a tendency to a higher proximal filling – 81 versus 75% – but the difference did not achieve statistical significance (p = 0.057). There was also a marginal association with the distal femoral width and the presence of a fracture (p = 0.062). Based on this study population, there were no differences in the shape of the femur (femoral offset, cervico-diaphyseal angle, canal flare index, proximal width, width at the calcar, cortical index) between the groups.

Of the 13 fractured femurs, eight had the stem aligned in neutral, so broaching in the wrong direction did not affect the risk of suffering a fracture. The difference in the height of the femoral cut was also not significantly different between both groups.

The prevalence of radiolucent lines was less frequent in the fractured femurs – 5 of 13 cases (61.5%) – than in the non-fractured femurs – 66 of 104 (63.4%); however, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.098) (Table 2). Only one of the implants in the fracture group had a stable fibrous union, whereas in the non-fractured group 24% of the implants had a stable fibrous union. Rounding of the calcar was also less frequent in the fractured group – 7 of 13 cases – than in the non-fractured group – 74 cases (71.1%). Based on the results of our study group, there were no differences in the HHS between the groups.

Table 2.

Radiolucent lines found in the different Gruen zones

| Fractured group | Non-fractured group | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 | 4 | 61 | 65 |

| Zone 2 | 2 | 18 | 20 |

| Zone 3 | 1 | 24 | 25 |

| Zone 4 | 2 | 40 | 42 |

| Zone 5 | 1 | 29 | 30 |

| Zone 6 | 1 | 24 | 25 |

| Zone 7 | 2 | 11 | 13 |

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to evaluate possible risk factors for the appearance of intraoperative fractures during primary hip arthroplasty. Based on the number of cases evaluated in this study, we conclude that there were no differences in demographic data, the shape of the femur or other intraoperative variables. Berend et al. found a higher risk for an intraoperative fracture in patients with an underlying diagnosis of developmental dysplasia [2]. We only found one fracture in the seven cases of dysplasia treated and none in LCP, with a higher incidence of fractures in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, probably due to poor bone quality.

The classic risk factors for intraoperative femoral fracture include female gender, uncemented arthroplasty, previous surgery in the hip and revision surgery [18]. Meek et al., on the basis of revision surgery, determined the risk factors associated with an intraoperative fracture to be preoperative bone loss, low femoral cortex to canal ratio, underreaming and large diameter stems; however, they found no association with comorbidity or demographic data of the patients [16]. To our knowledge, our study is the first to be published on the risk factors in primary uncemented arthroplasty with a single design of the implant. We found that femurs with a greater proximal fill by the stem showed a tendency to suffer an intraoperative fracture, but the difference was not statistically significant.

The geometry of modern broaches widens the femoral canal mostly in the AP diameter, and the stem does not contact the medial cortex until insertion is almost completed. For this reason, greater strains are applied to the medial and anteromedial cortex of the femur. Experimental studies comparing the strains at the anteromedial and medial cortex during broaching and stem insertion, using different techniques, have shown that the geometry and material properties of the femur have a greater influence in terms of strain distribution than the implantation technique used [5]. Nevertheless, in our series, the majority of the fractures occurred during the insertion of the stem and were located in the calcar. We could not find any association with the geometry of the femur.

Our series revealed a higher incidence of fractures than other studies. While the design of this particular stem could be the reason for this result, comparative studies with other designs need to be carried out for supportive evidence. Toni reported a 13% incidence of intraoperative fractures with the Lord stem, whereas the incidence with an anatomical design was only 1.4% [25]. In cases of primary uncemented arthroplasty, Cameron found 47 femoral fractures (six of the greater trochanter, 26 of the calcar) in 679 THA in which a modular prosthesis was used, representing an incidence of 6.9%; there were no radiographic signs of loosening [3].

The effect of intraoperative fractures in bone ingrowth is controversial. Experimental models have shown an increase in micromotion and rotational instability which precludes bone ingrowth [7]. However, Sharkey et al., comparing the results of ten patients with fracture matched with 20 without signs of fracture, found no clinical or radiographic difference after 2.3 years of follow-up [22].

Long-term survival in these cementless cases is not compromised as long as fracture and prosthetic stability is achieved at the time of surgery. Berend et al. found 100% femoral component survival in 58 hips with intraoperative calcar fracture during a follow-up of 2–16 years [2]. Mont et al. reported excellent or good results after proper management in 18 of 19 intraoperative fractures [17]. Inadequate fixation of the fracture will lead to rotational instability or subsidence of the prosthesis. The different configuration of intraoperative fractures determine the treatment options. In our series, all of the fractures were undisplaced linear cracks that could be managed successfully with cerclage wiring.

Adequately managed intraoperative fractures have no significant effect on the functional outcome or radiographic evidence of bone ingrowth [16]. In our series of fractured femurs, the 2-year postoperative radiographic evaluation showed a better osteointegration. It is difficult to understand why this pattern occurred, although the femurs which sustained a fracture had a superior proximal filling by the stem, which possibly enhanced bone ingrowth. The pattern of fractures studied did not affect primary stability of the implants.

In conclusion, we were unable to find any specific risk factor in our series of patients. We suggest that intraoperative femoral fractures in cementless hip arthroplasty may be due to an excessive aggressiveness of the surgeon to obtain an excellent fit and fill or to the design of the instruments or implants. This latter possibility should be compared with other series using the same implant for supportive data. However, the occurrence of this type of fracture, if diagnosed during the procedure and properly treated, does not seem to compromise the result of the procedure.

References

- 1.Andrew TA, Flanagan JP, Gerundini M, Bombelli R (1986) The isoelastic, noncemented hip arthroplasty: Preliminary experience with 400 cases. Clin Orthop 206:127–138 [PubMed]

- 2.Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr, Mallory TH, Chonko DJ, Dodds KL, Adams JB (2004) Cerclage wires or cables for the management of intraoperative fracture associated with a cementless tapered femoral prosthesis: results at 2 to 16 years. J Arthroplasty 19:17–21 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Cameron HU (2004) Intraoperative hip fractures: ruining your day. J Arthroplasty 19:99–104 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Capello WN, Sallay PI, Feinberg JR (1994) Omniflex modular femoral component: Two-to-five year results. Clin Orthop 298:54–59 [PubMed]

- 5.Elias JJ, Nagao M, Chu YH, Lennox DW, Chao EY (2000) Medial cortex strain distribution during noncemented total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 370:250–258 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Engh CA, Bobyn JD (1988) The influence of stem size and extent of porous coating on femoral bone resorption after primary cementless hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 231:7–28 [PubMed]

- 7.Engh CA, Glassman AH, Griffin WL, Mayer JG (1988) Results of cementless revision for failed cemented total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 235:91–110 [PubMed]

- 8.Falez F, Santori N, Panegrossi G (1998) Intraoperative type I proximal femoral fractures. Influence on the stability of hydroxyl apatite-coated femoral components. J Arthroplasty 13:653–659 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Fitzgerald RH, Brindley GW, Kavanagh BF (1988) The uncemented total hip arthroplasty: Intraoperative femoral fractures. Clin Orthop 235:61–66 [PubMed]

- 10.Gruen TA, McNeice GM, Amstutz HC (1979) “Modes of failure” of cemented stem-type femoral components: Radiographic analysis of loosening. Clin Orthop 141:17–27 [PubMed]

- 11.Harris WH (1969) Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty: an end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 51:737–755 [PubMed]

- 12.Johansson JE, Mc Broom R, Barrington TW et al (1981) Fracture of the ipsilateral femur in patients with total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 63A:1435–1442 [PubMed]

- 13.Lord G, Marotte J-H, Guillamon J-L, Blanchard J-P (1988) Cementless revisions of failed cemented and cementless total hip arthroplasties: 284 cases. Clin Orthop 235:67–74 [PubMed]

- 14.Mallory TH, Kraus TJ, Vaughn BK (1989) Intraoperative femoral fractures associated with cementless total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics 12:231–239 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Martell JM, Pierson RH, Jacobs JJ et al (1993) Primary total hip reconstruction with a titanium fiber-coated prosthesis inserted without cement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 75A:554–571 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Meek RM, Garbuz DS, Masri BA, Greidanus NV, Duncan CP (2004) Intraoperative fracture of the femur in revision total hip arthroplasty with a diaphyseal fitting stem. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 86-A:480–485 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mont MA, Maar DC, Krackow KA, Hungerford DS (1992) Hoop-stress fractures of the proximal femur during hip arthroplasty: Management and results in 19 cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 74B:257–260 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Moroni A, Faldini C, Piras F, Giannini S (2000) Risk factors for intraoperative femoral fractures during total hip replacement. Ann Chirurg Gynaecol 89:113–118 [PubMed]

- 19.Paprosky WG, Greidanus NV, Antoniu J (1999) Minimum 10-year-results of extensively porous-coated stems in revision hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 369:119–130 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Schwatrz JT Jr, Mayer JG, Engh CA (1989) Femoral fracture during non-cemented total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 71-A:1135–1142 [PubMed]

- 21.Scott RD, Turner RH, Leitzes SM, Aufranc OE (1975) Femoral fractures in conjunction with total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 57-A:494–501 [PubMed]

- 22.Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Booth RE, Rothman RH (1992) Intraoperative femoral fractures in cementless total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Rev 21:337–342 [PubMed]

- 23.Singh M, Nagrath AR, Maini PS (1970) Changes in the Trabecular Pattern of the Upper End of the Femur as an Index of Osteoporosis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 52-A:457–467 [PubMed]

- 24.Taylor MM, Meyers MH, Harvey JP (1978) Intraoperative femur fractures during total hip replacement. Clin Orthop 137:96–103 [PubMed]

- 25.Toni A, Ciaroni D, Sudanese A, Femino F, Marraro MD, Bueno Lozano AL, Giunti A (1994) Incidence of intraoperative femoral fracture. Straight-stemmed versus anatomic cementless total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Belg 60:43–54 [PubMed]