Abstract

In the present article we examine the antiplasmodial activities of novel quinolone derivatives bearing extended alkyl or alkoxy side chains terminated by a trifluoromethyl group. In the series under investigation, the IC50 values ranged from 1.2 to ≈ 30 nM against chloroquine-sensitive and multidrug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum strains. Modest to significant cross-resistance was noted in evaluation of these haloalkyl- and haloalkoxy-quinolones for activity against the atovaquone-resistant clinical isolate Tm90-C2B, indicating that a primary target for some of these compounds is the parasite cytochrome bc1 complex. Additional evidence to support this biochemical mechanism includes the use of oxygen biosensor plate technology to show that the quinolone derivatives block oxygen consumption by parasitized red blood cells in a fashion similar to atovaquone in side-by-side experiments. Atovaquone is extremely potent and is the only drug in clinical use that targets the Plasmodium bc1 complex, but rapid emergence of resistance to it in both mono- and combination therapy is evident and therefore additional drugs are needed to target the cytochrome bc1 complex which are active against atovaquone-resistant parasites. Our study of a number of halogenated alkyl and alkoxy 4(1H)-quinolones highlights the potential for development of “endochin-like quinolones” (ELQ) bearing an extended trifluoroalkyl moiety at the 3-position that exhibit selective antiplasmodial effects in the low nanomolar range and inhibitory activity against chloroquine and atovaquone resistant parasites. Further studies of halogenated alkyl and alkoxy quinolones may lead to the development of safe and effective therapeutics for use in treatment or prevention of malaria and other parasitic diseases.

Introduction

Malaria is a potentially fatal tropical disease that is spread by mosquitoes from person to person and caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium. Plasmodium falciparum causes cerebral malaria, the most severe form of the infection, and it is responsible for most of the estimated 1 million deaths attributed to malaria annually (Greenwood, et al., 2005, Snow, et al., 2005). Pregnant women and young children are most likely to succumb to cerebral malaria and it is in treatment of these two vulnerable populations that the antimalarial armamentarium offers few options (Ashley, et al., 2006, Greenwood, 2006, Winstanley and Ward, 2006). The primary drugs for treatment of malaria have been the quinolines chloroquine (CQ), quinine (QN), and mefloquine and the antifolate combination of pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine. The usefulness of these drugs has greatly diminished due to the spread of drug-resistant strains of both P. falciparum and P. vivax (White, 2004, White, et al., 1999) throughout malarious regions of the world. Consequently, therapeutic options for treatment of malaria are dwindling and replacement drugs, the endoperoxide artesunate (Ashley and White, 2005, Edwards and Biagini, 2006, Meshnick, 2002) [including its formulation with other drugs, i.e., “artemisinin combination therapies”] and the atovaquone – proguanil combination known as Malarone® (Boggild, et al., 2007), offer a rather thin wall of protection against a total collapse in malaria chemotherapy. As a result there is an urgent need for developing new and safe drugs for treating or preventing malaria.

We recently described the structural optimization of acridones using antimalarial activity and lymphocyte cytotoxicity as criteria in calculating a value known as the in vitro therapeutic index that was used to guide further improvements (Winter, et al., 2006). A unique and defining feature of acridones optimized for antimalarial potency is the presence of an extended alkyl or alkoxy side chain that is terminated by one or more trifluoromethyl (CF3) groups. While it may be assumed that such modification would enhance in vivo efficacy by blocking or hindering catabolism of the side chain by host P450 enzymes, the striking enhancement of in vitro potency suggests that the CF3 groups are important in the antiplasmodial mode of action of the acridone constructs.

Our aim in the present study was to extend the structure-activity profiling of haloalkoxy/alkyl-bearing acridone molecules to include other aromatic ketones, in an effort to find a basic core structure that retains selective and potent activity against Plasmodium parasites. Herein we focus our studies on quinolones and present results on the antiplasmodial mechanism of these compounds.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Unless otherwise stated all chemicals and reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company in St. Louis, MO (USA). SYBR Green I dye, used for determination of antiplasmodial IC50 values, was purchased from Molecular Probes (now Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA). RPMI-1640, gentamicin, and Albumax II® were purchased from Gibco (now Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Blood, a source for red cells used to culture the parasite, was purchased from Lampire Biologicals (Pipersville, PA, USA). White blood cells were removed by centrifugation followed by removal of the buffy coat and uppermost red blood cells. 96-well Oxygen biosensor plates were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). 7-Methoxy-3-ethoxycarbonyl-4(1H)-quinolone was prepared by the method of Lauer et al. (Lauer, et al., 1946). 3-Heptyl-7-methoxy-2-methyl-4(1H)-quinolone (Endochin) was synthesized by the method of Salzer et al. (Salzer, et al., 1948). The synthesis of selected 4(1H)-quinolones is described below. Each of the quinolone derivatives was characterized by 1H-(500 MHz) nmr and high-resolution mass spectrometry to ensure identity and purity prior to use in this study.

General and specific approaches to synthesis of selected quinolone derivatives

Synthesis of 3-ethoxycarbonyl-7-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyloxy)-4(1H)-quinolone (compound 6)

The procedure (Gould-Jacobs quinoline reaction (Gould and Jacobs, 1939)) required initial synthesis of m-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyloxy)-aniline, obtained by heating m-nitrophenol (3.45 g), ethanol (50 ml), KOH (1.5 g) and CF3(CH2)5Br (Oakwood, Columbia, South Carolina, U.S.A.) for 3 days, followed by cooling, filtering, and concentrating. The residue, an oil, had M+ = 277 (26%), 1H-nmr spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3): Ring system: δ2 = 7.71 ppm, t, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H; δ4 = 7.81, d-d-d, J24 = 2.20, J45 = 8.24, J46 =0.92, 1H; δ5 = 7.42, t, J = 2.2, 1H; δ6 = 7.22, d-d-d, J26 = 2.2, J56 = 8.2, J46 =0.92, 1H. Substituents: δOCH2 = 4.05, t, J = 6.26, 3H; δCH2(β-δ) = 1.60, m, 2H; 1.66, m, 2H; 1.86, m, 2H; δCH2CF3 = 2.2, m, 2H.

The crude m-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyloxy)-nitrobenzene (derived from the previous step) was heated with 100 ml of HClconc. + 28.5 g SnCl2 for 1 hour; the color turned to pale yellow in about 30 min. After 1 hour, the volume was reduced to about 50 ml by boiling off hydrochloric acid. After cooling, water (300 ml) and NaOH (40 g NaOH + 130 ml water) were added. Once the mixture had cooled again, it was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 150 ml) and the combined extracts were then washed with 50 ml of water. Drying (Na2SO4) and removal of solvent gave 5.31 g of crude m-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyloxy)-aniline as a pale yellow oil. A sample was purified by chromatography but the bulk was used in the condensation step with ethoxymethylenemalonic ester directly. M+ = 247 (28%), 1H-nmr spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3): Ringsystem: δ2 = 6.22 ppm, t, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H; δ4 = 6.30, d-d-d, J24 = 2.3, J45 = 8.14, J46 =0.76, 1H; δ5 = 6.27, t, J = 8.0, 1H; δ6 = 6.27, d-d-d, J26 = 2.15, J56 = 8.0, J46 =0.9, 1H. Substituents: δOCH2 = 4.14, t, J = 6.26; 3H; δCH2(β-δ) = 1.53, m, 2H; 1.62, m, 2H; 1.77, m, 2H; δCH2CF3 = 2.1, m, 2H; δNH2 = 3.65, s, br., 2H.

The method employed in the condensation reaction to prepare 3-ethoxycarbonyl-7-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyloxy)-4(1H)-quinolone was based on the methods of Lauer et al. (Lauer, et al., 1946) except that the m-alkoxy-aniline used was m-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyloxy)-aniline. Crude m-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyloxy)-aniline (5.12 g) and 4.65 g of diethyl ethoxymethylenemalonate (1 eq.) were mixed and set aside for 1 hour; warming was noticed. Subsequently, the mixture was heated at 100°C for 3 hours, after which time all volatile components were removed under vacuum (0.02 atm., 70°C), weight of residue = 8.43 g. This product showed the correct 1H-nmr spectrum for the expected product diethyl m-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyloxy-anilino)-methylene-malonate and was used without further characterization. It was dissolved in 15 ml of Dowtherm A (see note below) with slight warming and added dropwise to 50 ml of boiling Dowtherm A over a period of 5 minutes, the boiling conditions were maintained for another 7 minutes and then the mixture was kept at room temperature overnight. 4.8 g of beige, small needles were filtered off, after re-crystallization from 75 ml of dimethylformamide, 4.53 g (59% of theoretical), m.p. = 272–274°C. 1H-nmr spectrum (500 MHz, d6-DMSO): Ringsystem: δ2 = 8.48 ppm, d, J = 6.55 Hz, 1H; δ4(OH) = 12.07, d, J ≈ 6.5, 0.9H; δ5 = 8.04, d, J = 9.6, 1H; δ6 = 6.99, d-d, J ≈ 2, J ≈ 9.6, 1H; δ8 ≈ 6.92, d, J ≈ 2, H(6) + H(8) overlap, together 2H. Substituents: Side chain (pos.7): δOCH2 = 4.07, t, J = 6.20; 3H; δCH2(β-δ) = 1.53, m, 4H; 1.8, m, 2H; δCH2CF3 = 2.2, m, 2H. COOCCH2CH3: δCH2 = 4.19, quart., J = 7, 2H; δCH3 = 1.27, t, J = 7, 3H. 19F-nmr spectrum (84.7 MHz, CDCl3): φ = −64.4 ppm, t, J = 11.3 Hz.

Synthesis of 7-methoxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone (compound 7)

The method utilizes the Conrad-Limpach reaction (Conrad and Limpach, 1887, Conrad and Limpach, 1891, Limpach, 1931), which consists of condensing a substituted (position 2) acetoacetic ester with an aniline, which provides a 2-alkyl-3-phenylamino crotonic ester (alternatively formulated as a Schiff base) and is followed by ring-closure in a high-boiling solvent, e.g., Dowtherm A, a high-boiling (atm. p) at ≈250°C, mixture of 73.5% diphenylether and 26.5% biphenyl, to form the desired quinolone.

A solution of sodium (0.50 g) in ethanol (50 ml) was added to ethyl acetoacetate (2.83 g), then 6-bromo-1,1,1-trifluoro-hexane (Oakwood, Columbia, South Carolina, USA) (4.76 g), and the mixture was heated at reflux temperature overnight. The solvent was removed (0.03 atm., 40°C), and after addition of water (50 ml) and HClconc. (5 drops), extraction (2 × 40 ml ethyl acetate) provided an oily residue (4.83 g) of ethyl 2-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-acetoacetate, gc-ms: 268 (M+), 1 %, 223 (M-OC2H5)+, 10%, which was used without further purification. The whole amount of this crude acetoacetate, m-anisidine (2.23 g, 1 eq.), benzene (100 ml) and HClconc. (5 drops) was heated to boiling temperature, while water was removed azeotropically. This step required 3 days to reach near-completion. The solvent was removed (rotary evaporator) and the residue dissolved in 25 ml of Dowtherm A and added dropwise over the course of 5 minutes to 50 ml of boiling Dowtherm A. Boiling was maintained for an additional 15 minutes and the mixture was allowed to cool and stand at ambient temperature for 1 hour. Filtration and washing with hexane gave 1.98 g of pale brown crystals, and after re-crystallization from acetone to effect separation of the 5- and 7-positional isomers 1.55 g, or 20.3 % of theory, m.p. = 215–217°C. Gc-ms (DB5, 30 meters, 150°C, 2 min, then at 11°C/min. → 280°C: 327 (M+), 18 %; 203 (M- (CH2)4CF3+H)+, 100 %. 1H-nmr spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3): Ringsystem: δ5 = 8.25 ppm, d, J56 = 9.0 Hz, 1H; δ6 = 6.88, d-d, J56 = 9.0, J68 = 2.3, 1H; δ8 = 6.70, d, J = 2.3, 1H. Substituents: δOCH3 = 3.81, s, 3H; δNH = 10.5, 0.8H; δCH3(2) = 2.45, s, 3H; δCH2(α) = 2.62, m, 2H; δCH2(β-δ) = 1.50, m, 2H; 1.37, m, 4H; δCH2CF3 = 2.1, m, 2H. 19F-nmr spectrum (84.7 MHz, CDCl3): φ = −64.4 ppm, t, J = 11.5 Hz.

7-Hydroxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone (compound 8)

7-Methoxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone (0.50 g), phenol (5.4 g) and hydriodic acid (57 %, 12 ml) were heated at reflux temperature for 2 hours. After cooling, water was added (80 ml) and the product extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 30 ml), the combined extracts washed with water (5 × 20 ml, ending with a pH ≈6). The solvent was evaporated and most of the remaining phenol removed by sublimation at 70 – 80°C (high vacuum). The residue was re-crystallized from ethanol, leaving 0.31 g of white, fluffy product; additional product (0.08 g) was obtained from the mother liquor by precipitation with water and re-crystallizing from ethanol. Yield = 0.39 g (81 %). The sample was dried at 100°C/ high vacuum/ 2 hours in order to remove absorbed ethanol. M.p. = 224–225°C. Gc-ms (DB5, 30 m., 150°C, 2 min, then at 11°C/min. → 280°C): 313 (M+), 21 %; 189 (M-(CH2)4CF3+H)+, 100 %. 1H-n.m.r. spectrum (500 MHz, (CD3)2SO): Ringsystem: δ5 = 7.88 ppm, d, J56 = 9.1 Hz, 1H; δ6 = 6.72, d-d, J56 = 9.1, J68 = 1.9, 1H; δ8 = 6.77, d, J = 1.9, 1H. Substituents: δOH(7) = 11.26, s, 1H; δCH3(2) = 2.35, s, 3H; δCH2(α) = 2.45, m, 2H; δCH2(β-δ) = 1.50, m, 2H; 1.38, m, 4H; δCH2CF3 = 2.2, m, 2H; δNH = 10.2,1H. 19F-nmr spectrum (84.7 MHz, CDCl3): φ = −64.6 ppm, t, J = 11.5 Hz.

Synthesis of 7-methoxy-2-methyl-3-(11,11,11-trifluoroundecyl)-4(1H)-quinolone (compound 9)

Synthesis of this compound was analogous to the method provided above for 7-methoxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone except for the use of 3.45 g CF3(CH2)10Br (from SF4 and 11-bromoundecanoic acid) instead of CF3(CH2)5Br. To effect crystallization from Dowtherm A hexane was added. After standing overnight, a crystalline precipitate had formed which was filtered off and washed with a small amount of acetone. Recrystallization (1st from alcohol, 2nd from acetone) provided 0.34 g of whitish shiny soft crystals of the desired 7-isomer, homogeneous by thin-layer chromatography and 1H-nmr spectroscopy, which exhibited the required spectral pattern for this compound. Yield = 11.2% of theory, m.p. = 186–187°C. Gc-ms (DB5, 30 meters, 150°C, 2 min, then at 11°C/Min. → 280°C): 397 (M+), 11 %; 203 (M-(CH2)9CF3+H)+, 100%.

1H-nmr spectrum (500 MHz, CDCl3): Ringsystem: δ5 = 8.26 ppm, d, J56 = 9.0 Hz, 1H; δ6 = 6.85, d-d, J56 = 9.0, J68 = 2.3, 1H; δ8 = 6.74, d, J = 2.3, 1H. Substituents: δOCH3 = 3.70, s, 3H; δNH = 10.1, 0.9H; δCH3(2) = 2.47, s, 3H; δCH2(α) = 2.63, m, 2H; δCH2(β-ι) = 1.51, m, 2H; 1.32, m, 2H; 1.21, m, 12H; δCH2CF3 = 2.1, m, 2H. 19F-nmr spectrum (84.7 MHz, CDCl3): φ = −64.4 ppm, t, J = 11.6 Hz.

Parasites

Plasmodium falciparum strains D6 and Dd2 were obtained from the MR4 (ATCC Manassas, VA, USA). D6 is sensitive to chloroquine but mildly resistant to mefloquine (Oduola, et al., 1987) while Dd2 is resistant to multiple quinoline and antifolate antimalarial agents as summarized by Singh (Singh and Rosenthal, 2001). Tm90-C2B (provided by Dr. Dennis Kyle, WRAIR) is resistant to atovaquone and chloroquine (Korsinczky, et al., 2000).

Parasite culture and drug susceptibility assays

Four different laboratory strains of P. falciparum were cultured in human erythrocytes by standard methods under a low oxygen atmosphere (5% O2, 5% CO2, 90% N2) in an environmental chamber (Trager and Jensen, 1976). The culture medium was RPMI 1640, supplemented with 25 mM HEPES buffer, 25 mg/L gentamicin sulfate, 45 mg/L hypoxanthine, 10 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine, and 0.5% Albumax II (complete medium). The parasites were maintained in fresh human erythrocytes suspended at a 2% hematocrit in complete medium at 37°C. Stock cultures were sub-passaged every 3 to 4 days by transfer of infected red cells to a flask containing complete medium and uninfected erythrocytes.

In vitro antimalarial activity of the test compounds was assessed by the SYBR Green I fluorescence-based method (the so-called “MSF assay”) described previously by us (Smilkstein, et al., 2004) with minor modifications (Winter, et al., 2006). The experiments were set up in triplicate in 96 well plates with two-fold dilutions of each drug across the plate in a total volume of 100 microliters and at a final red blood cell concentration of 2% (v/v). Stock solutions of each drug were prepared by dissolving in DMSO at 10mM. The dilution series was initiated at a concentration of 1µM and the experiment was repeated beginning with a lower initial concentration for those compounds in which the IC50 value was below 10nM. In every case, an additional determination was performed to ensure bracketing of the IC50 value by at least an order of magnitude. Automated pipeting and dilution was carried out with the aid of a programmable Precision 2000 robotic station (BioTek, Winooski, VT). An initial parasitemia of 0.2% was attained by addition of normal uninfected red cells to a stock culture of asynchronous parasite infected red cells (PRBC). The plates were incubated for 72 hrs at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2, 5% O2, and 90% N2. After this period the SYBR Green I dye-detergent mixture (100µl) was added and the plates were incubated at room temperature for an hour in the dark and then placed in a 96-well fluorescence plate reader (Spectramax Gemini-EM, Molecular Diagnostics) for analysis with excitation and emission wavelength bands centered at 497 and 520 nm, respectively. The fluorescence readings were plotted against the logarithm of the drug concentration and curve fitting by nonlinear regression analysis (GraphPad Prism software) yielded the drug concentration that produced 50% of the observed decline from the maximum readings in the drug-free control wells (IC50).

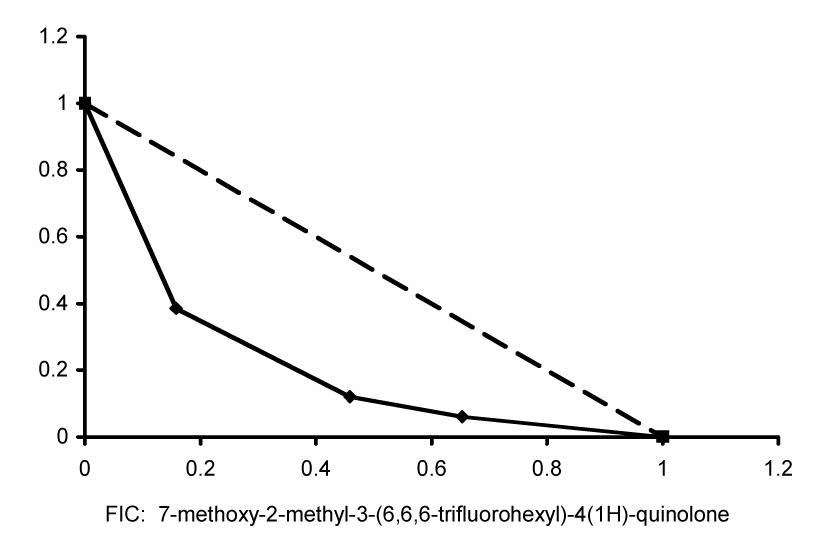

Isobolar analysis of quinolone-clopidol combinations

Dose response assays were first carried out to obtain the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 7-methoxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone (7) and clopidol. For drug interaction studies, three fixed concentrations of the quinolone derivative were added to wells containing clopidol that had been diluted in a two-fold series from 10 to 0.1 µM. The effect of the quinolone on the antiplasmodial activity of clopidol was assessed by comparing concentration-response curves for clopidol alone and in the presence of 7, and were expressed as the fractional inhibitory concentrations (FICs) where FIC was calculated by the following formula: FIC (A) = IC50 of drug A in combination/IC50 of drug A alone; FIC (B) = IC50 of drug B in combination/IC50 of drug B alone. The isobologram was constructed by plotting FICs for combinations of clopidol and the quinolone derivative. A straight diagonal line (FIC index = 1) on the isobologram indicates a purely additive effect between the two drugs. A concave curve below the theoretical line of addition (FIC index <1.0) indicates synergy between the drugs in combination, while a convex curve above the line (FIC index >1.0) indicates an antagonistic interaction between the drugs.

Cytotoxicity assessment vs. mitogen-induced lymphocyte proliferation

The general cytotoxicity of each derivative was determined by resazurin reduction assay previously described by us (Winter, et al., 2006). Thus, we employed the resazurin reduction assay to assess the cytotoxicity of each aromatic ketone against murine splenic lymphocytes induced to proliferate and differentiate by concanavalin A. IC50 values were determined from the plot of fluorescence vs. drug concentration compared to a no-drug control. The primary goal of the drug testing studies was the determination of IC50 values for drug activity (vs. PRBC) and drug toxicity (vs. splenic lymphocytes). The ratio of the 2 IC50s, i.e., IC50 (vs. lymphocytes) / IC50 (vs. PRBC) was used to generate a value reflecting the in vitro therapeutic index (IVTI) for each compound.

Rate of oxygen consumption by Plasmodium yoelii infected erythrocytes

Preliminary experiments demonstrated that P. yoelii-infected red blood cells exhibited a higher basal respiratory rate than P. falciparum infected red blood cells and thus the former were employed for these mechanistic studies. Atovaquone and chloroquine sensitive P. yoelii (K strain) infected red cells were obtained from infected mice (CF-1, female) with local IACUC approval #2106. The assay is based on the use of BD™ Oxygen Biosensor plates (Guarino, et al., 2004) that have an oxygen-sensitive dye embedded in a matrix at the bottom of each well. Oxygen quenches the fluorescence of the dye in a concentration dependent manner. Normal parasite respiration processes rapidly deplete the surrounding medium of oxygen thereby allowing the dye to fluoresce. Experiments were set up in a typical 96-well plate and the contents of each well were transferred to a biosensor plate to initiate the reactions, allowing 10 minutes after setup for equilibration and sedimentation of the assay components. ≈60 million parasitized red cells (PRBC) (final hematocrit = 12.5%) were incubated in phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4, w/o Ca++ or Mg++) in the presence or absence of compounds and in a total volume of 80µl. The set-up was conducted at 4°C and then the plates were transferred to a Gemini EM 96-well plate fluorometer pre-equilibrated to 37°C. The instrument was programmed to take readings (485nm excitation/630nm emission) at 2-minute intervals over a 1 hr period.

Results

In vitro activity and pharmaco-resistance pattern of haloalkyl and haloalkoxy-containing quinolones against a panel of P. falciparum parasites

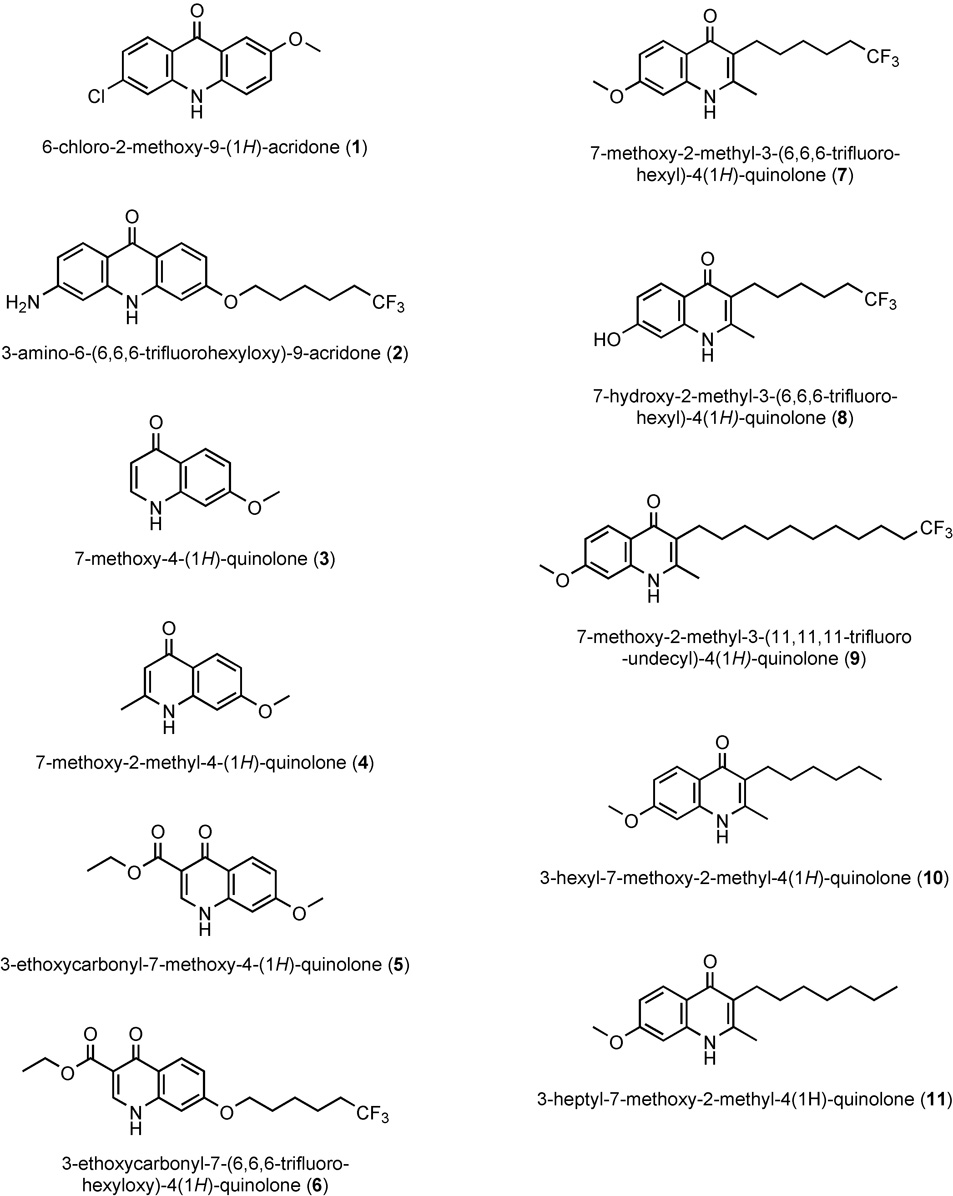

Table 1 gives the activities found for selected quinolones and acridones in the antimalarial and cytotoxicity screens together with the ratio of these values reflecting a measure of the “in vitro therapeutic index” (IVTI). Chemical structures for each quinolone and acridone derivative used in this study are shown in Figure 1. For this analysis we included three different strains of P. falciparum in order to assess for cross-resistance to existing antimalarials. D6 is sensitive to the action of chloroquine and moderately resistant to mefloquine while Dd2 is resistant to multiple drugs including chloroquine, mefloquine, quinine, pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine. Tm90-C2B is resistant to atovaquone and chloroquine. For this study we synthesized and evaluated compounds that were modified to contain an extended alkyl or alkoxy group, terminated by CF3, and we compared their antiplasmodial activities in the three chosen parasite strains.

Table 1.

Antiplasmodial activities of selected haloalkoxy and haloalkyl-quinolones and acridones in drug sensitive and multidrug resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum.

| Compd. # | Compound name | IC50 values, nM* | Cross-resistance index | IVTI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haloalkyl & haloalkoxy-acridones and quinolones | D6 | Dd2 | Tm90-C2B | Tm90-C2B/D6 | MSLC | MSLC/D6** | |

| 1 | 6-chloro-2-methoxy-9(1H)-acridone | 45 | 65 | >2,500 | >555 | >25,000 | >1,150 |

| 2 | 3-amino-6-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyloxy)- 9(1H)-acridone | 0.02 | 0.02 | 78 | 3,900 | >25,000 | >25,000 |

| 3 | 7-methoxy-4(1H)-quinolone | >2,500 | >2,500 | >2,500 | - | >25,000 | NA |

| 4 | 7-methoxy-2-methyl-4(1H)-quinolone | 2,300 | 1,260 | 1,290 | 0.6 | >25,000 | >11 |

| 5 | 7-methoxy-3-ethoxycarbonyl-4(1H)-quinolone | 325 | 303 | 750 | 2.3 | >25,000 | >77 |

| 6 | 3-ethoxycarbonyl-7-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyloxy)-4(1H)-quinolone | 1.2 | 1.2 | 270 | 225 | >25,000 | >20,800 |

| 7 | 7-methoxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone | 32 | 30 | 66 | 2.1 | >25,000 | >780 |

| 8 | 7-hydroxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone | 680 | 390 | 1,360 | 2.0 | >25,000 | >37 |

| 9 | 7-methoxy-2-methyl-3-(11,11,11-trifluoroundecyl)-4(1H)-quinolone | 1.25 | 1.44 | 4.7 | 3.8 | >25,000 | >20,000 |

| 10 | 3-hexyl-7-methoxy-2-methyl-4(1H)-quinolone | 7.3 | 5.5 | 26.6 | 3.6 | >25,000 | >3,400 |

| 11 | 3-heptyl-7-methoxy-2-methyl-4(1H)-quinolone (Endochin) | 3.2 | 2.8 | 17.4 | 5.4 | >25,000 | >7,800 |

| Antimalarials and known respiratory inhibitors | |||||||

| Chloroquine | 6.4 | 113 | 134 | 20.9 | 3,900 | ≈600 | |

| Artemisinin | 0.81 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 2.6 | >25,000 | >30,000 | |

| Atovaquone (Qo site inhibitor of cytochrome b) | 0.3 | 0.5 | 5,090 | ≈17,000 | >25,000 | >25,000 | |

Data are the average of at least 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate with the aid of a Precision 2000 robotic pipeting station. IC50 values were determined by the MSF assay (Smilkstein et al., AAC, 2004). MSLC = Murine splenic lymphocytes. Cytotoxicity was determined using a 48-hr MSLC–concanavalin A induced proliferation assay using the Alamar Blue fluorescence method. IVTI = in vitro therapeutic index calculated from the ratio of IC50 values of the cytotoxicity observed in the blastogenesis assay and antimalarial potency against the D6 strain of P. falciparum. NA = not applicable.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of quinolones and acridones employed in this study.

The first two compounds shown in the Table, 6-chloro-2-methoxy-9(1H)-acridone (compound 1) and 3-amino-6-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyloxy)-acridone (compound 2), were profiled in a recent article in this journal (Winter, et al., 2006). Both of the acridones exhibit potent antiplasmodial activity against strains D6 and Dd2 however the inhibitory effect is greatly diminished against Tm90-C2B. Given that atovaquone resistance in Tm90-C2B (Table 1) is linked to a specific mutation in the mitochondrial gene encoding cytochrome b (Srivastava, et al., 1999), decreased potency for the two acridones against this strain is consistent with the notion that both compounds target the cytochrome bc1 complex as their primary mode of action against the Plasmodium parasite. It is noteworthy that 2 contains an extended haloalkoxy side chain while 1 does not.

Structurally simple quinolones lacking an extended alkyl or alkoxy side chain (i.e., compounds 3, 4, and 5) yielded IC50 values that ranged from insignificant (3; D6 IC50 >>2.5µM), to modest (4; D6 IC50 = 2.3µM), to respectable (5; D6 IC50 = 325nM). The antiplasmodial enhancing effect of adding an extended haloalkoxy side chain to the quinolone core can be readily appreciated by comparing the potency of quinolone esters 5 and 6, the latter containing the lengthy side chain. Thus, 3-ethoxycarbonyl-7-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyloxy)-4(1H)-quinolone (6) exhibits over 250 times greater antimalarial activity against D6 and Dd2 (1.2nM) compared to the corresponding quinolone ester lacking this structural feature. It is noteworthy that this increase in potency was accompanied by a significant cross-resistance to atovaquone as evidenced by the 270nM IC50 that was recorded for the drug against Tm90-C2B.

Placement of a trifluorohexyl group at the 3-position of the quinolone system also produced an impressive antiplasmodial enhancement, i.e., ≈70-fold, over the corresponding unsubstituted derivative (compare compounds 4 and 7). 7-Methoxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone (7) exhibited an IC50 of ≈30nM against the chloroquine sensitive D6 clone as well as multidrug resistant Dd2. Most notably, for this 3-alkyl quinolone derivative the improvement in potency was not accompanied by a significant atovaquone cross resistance since the observed IC50 for the Tm90-C2B isolate was increased only ≈2-fold to 66nM. Furthermore, this compound was without deleterious effects on the proliferation of mitogen-induced murine lymphocytes even at the highest tested concentration of 25µM, yielding a remarkable IVTI of over 780.

Given the impressive potency and selective action of 7 together with its inhibitory activity against multidrug-and atovaquone-resistant Plasmodium parasites we synthesized a few additional compounds to begin to explore the structure-activity profile of similar 3-alkyl-4(1H)-quinolones. Conversion of the 7-methoxy group of 7 to hydroxy (8) leads to a significant loss of activity (32nM ⇒ 680nM for compound 8) while lengthening of the haloalkyl side chain improves potency (32nM ⇒ 1.25nM for compound 9). A comparison of compounds 7 and 10 allows for determination of the effect of the fluorine atoms located at the terminal end of the side chain. Interestingly, it was observed that the corresponding hexyl derivative (10) was more potent than the trifluorohexyl analog, however, the former exhibited a greater degree of cross-resistance in atovaquone resistant Tm90-C2B (i.e., 2.1-fold vs. 3.6-fold). The heptyl derivative (11), 3-heptyl-7-methoxy-2-methyl-4(1H)-quinolone, also known as Endochin (Salzer, et al., 1948), exhibited even greater in vitro antimalarial activity however the degree of resistance observed against the atovaquone resistant strain was increased to 5.4-fold. Taken together, it would appear that “endochin-like quinolones” (EQL) represent a superior subclass of quinolones because of the potential for development of haloalkyl derivatives with potent antimalarial activity and without significant cross-resistance to any clinical agent in current use for treatment of malaria.

Antimalarial synergism with clopidol

We next set out to evaluate the pharmacological interaction between 7-methoxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone (7), considered prototypical of the ELQ derivatives profiled here, and clopidol. Quinolones with extended alkyl and alkoxy side chains have been shown to exhibit potent antimalarial activity in animal models and some of them have been used as anticoccidial agents (Williams, 1997) in combination with clopidol, especially in the prevention of Eimeria infections in chickens (Fry and Williams, 1984). It is also known that clopidol, and pyridone derivatives of it, act synergistically with atovaquone as determined by standard antimalarial isobolar testing (Canfield, et al., 1995, Pudney, et al., 1992). Thus, clopidol and 7 were tested in checkerboard fashion across a 96-well plate at concentrations that ranged downward from their respective IC50 values. To obtain numeric values for the drug interaction, results were expressed as Fractional Inhibitory Concentrations (FICs). Isobolograms were then constructed from the resulting FICs, a concave curve indicating synergy, a straight line shows an additive response, and a convex curve is evidence of antagonism. A typical isobologram of the quinolone-clopidol combination is presented in Figure 2; the interaction is clearly synergistic and similar to that which has been described for atovaquone-clopidol combinations (Canfield, et al., 1995, Pudney, et al., 1992).

Figure 2.

Isobolar analysis of the antiplasmodial activity of 7-methoxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone (7) and clopidol. Shown are the results from a single representative experiment which did not differ significantly from two other identical experiments conducted independently.

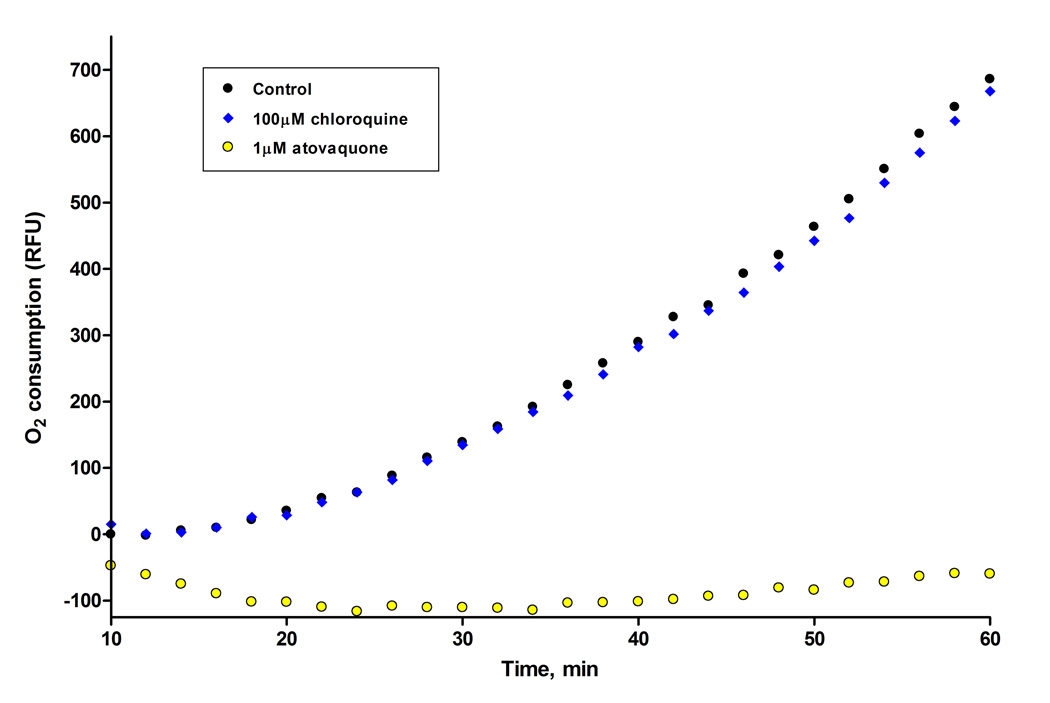

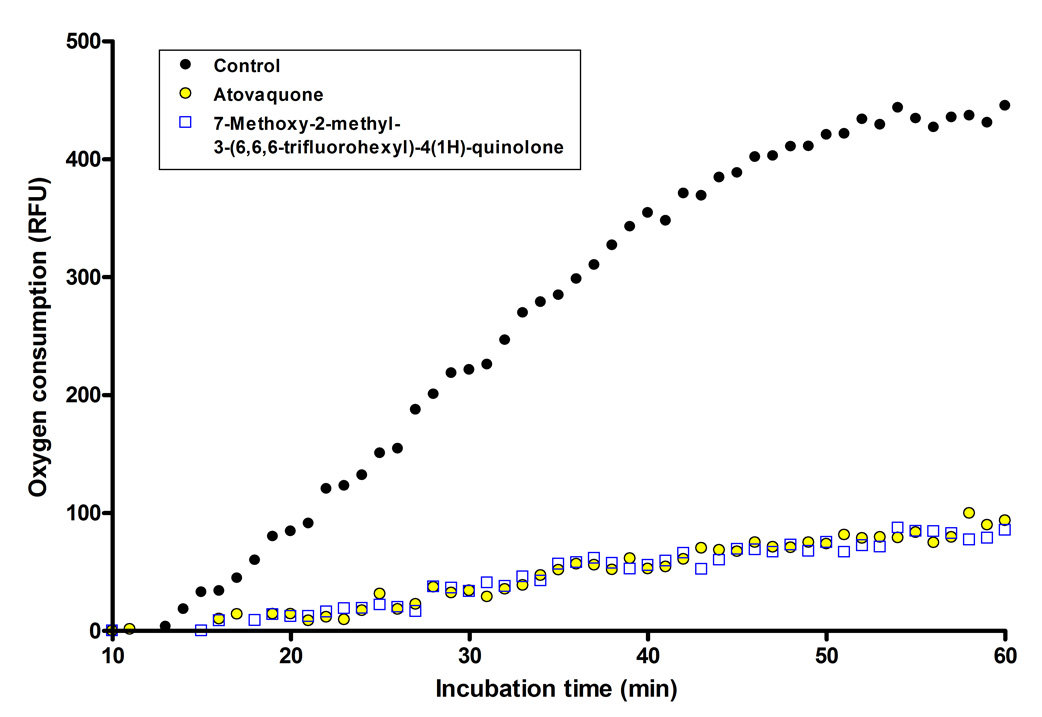

Inhibition of parasite oxygen consumption by 7-methoxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone

We tested the 7-methoxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone (7) for the ability to interfere with parasite respiration processes using BD oxygen biosensor plates. These biosensor plates have an oxygen-sensitive dye (tris 1,7-diphenyl-1,10 phenanthroline ruthenium (II) chloride) embedded in the matrix at the bottom of each well. Oxygen quenches the fluorescence of the dye in a concentration dependent manner; therefore an increase in fluorescence corresponds to oxygen consumption. Results from representative experiments are shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4 comparing the inhibition profile of 7 and atovaquone, and including chloroquine as a negative control owing to the current view that it acts to block hemozoin formation (Bray, et al., 2006, Chong and Sullivan, 2003) and thus is not believed to interfere directly with parasite respiratory processes. In evaluation of the assay using positive and negative control drugs, data presented in Figure 3 show that 1µM atovaquone completely inhibits oxygen consumption by murine P. yoelii infected red blood cells over the entire hour of experimentation, consistent with previous reports of atovaquone action (Fry, et al., 1984, Fry and Pudney, 1992). Over the same time interval 100µM chloroquine was without effect on parasite oxygen consumption (Figure 3); note that this concentration is ≈10,000 times greater than the IC50 value for chloroquine against drug susceptible strains of P. falciparum. In a separate experiment carried out under the same conditions we observed a similar degree of inhibition of parasite oxygen consumption by quinolone derivative 7 and atovaquone, each at a concentration of 250nM (Figure 4). In separate experiments (not shown here) we have observed that the 6-amino acridone construct (2) also blocks oxygen consumption by P. yoelii infected red cells.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the inhibitory of effect of atovaquone and chloroquine on oxygen consumption by P. yoelii infected erythrocytes. Note that the y-axis reflects relative fluorescence units and oxygen consumption is reported as an increase in fluorescence from the oxygen sensitive dye embedded in the matrix.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the inhibitory effect of 7-methoxy-2-methyl-3-(6,6,6-trifluorohexyl)-4(1H)-quinolone (7) and atovaquone on oxygen consumption by P. yoelii infected erythrocytes. Note that the y-axis reflects relative fluorescence units and oxygen consumption is reported as an increase in fluorescence from the oxygen sensitive dye embedded in the matrix.

Discussion

The results presented in this paper demonstrate that haloalkyl- and haloalkoxy quinolones show a high level of antimalarial action against Plasmodium falciparum strains that are highly resistant to a multiplicity of 4-amino-quinolines and antifolate drugs in clinical use today. Depending on the structure of the quinolone derivative, a modest to significant cross-resistance in the atovaquone-resistant clinical isolate Tm90-C2B is observed, providing evidence in support of a common mechanistic determinant – the parasite’s cytochrome bc1 complex. Further evidence in support of the notion that the quinolone derivatives target the parasite’s respiratory apparatus include the capacity to rapidly and potently inhibit oxygen consumption by the murine malaria species P. yoelii.

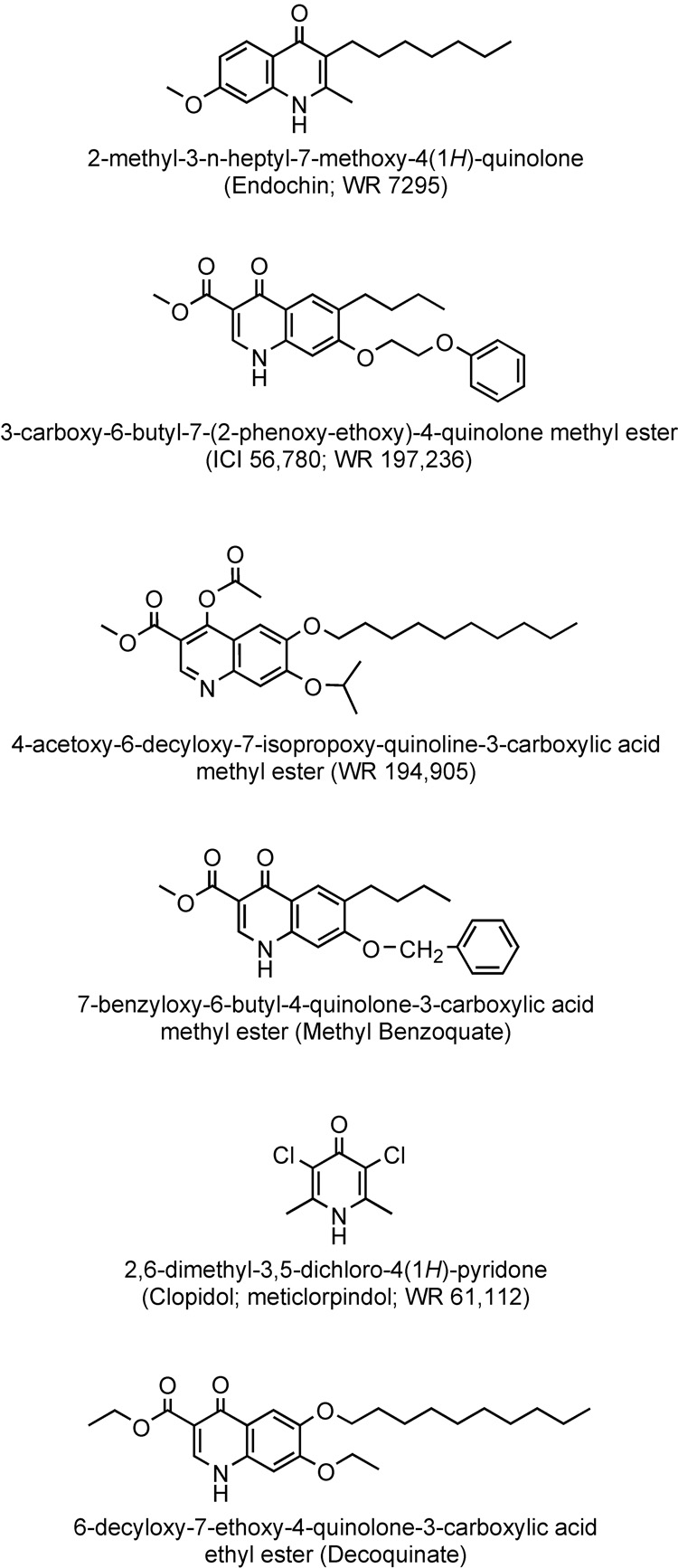

It is noteworthy that 4(1H)-quinolones (see Figure 5 for structures) bearing extended (4 or more carbon atoms in length) alkyl and alkoxy side chains have been previously investigated for treatment and prevention of malaria. Discovered nearly 70 years ago, “Endochin” (3-n-heptyl-7-methoxy-2-methyl-4(1H)-quinolone) (Casey, 1974, Salzer, et al., 1948) was considered a very promising lead with excellent therapeutic activity in an avian model of malaria but it failed in clinical trials (Kikuth and Mudrow-Reichenow, 1947). [The term endochin derives from its action upon the endothelial forms of avian malaria.] It is noteworthy that Kikuth and Mudrow-Reichenow observed that endochin also acted as a true causally prophylactic antimalarial in the avian system.

Figure 5.

Chemical structures of selected alkyl- and alkoxy-quinolones and pyridones that have been evaluated as antimalarials in the past.

Quinolone esters were studied by Ryley and Peters (Ryley and Peters, 1970) who focused primarily on the quinolone ester, ICI 56,780, which demonstrated a suppressive effect on P. berghei infections at a daily subcutaneous dose on the order of 1 to 2.5 mg/kg in a standard 3-day protocol while a complete prophylactic effect against P. berghei in mice and P. cynomolgi in rhesus monkeys was brought about by subcutaneous dosing in the range of 10 to 30 mg/kg. It was noted that resistance to this alkoxy-quinolone developed relatively easily in P. berghei when the drug was used alone and for this reason various combinations were tested. The investigators found the combination of chlorocycloguanil and ICI 56,780 to be synergistic and curative in treatment of blood-induced P. berghei infections in mice. A marked potentiation was also demonstrated in combinations of the drug with sulfadoxine.

Davidson et al. (Davidson, et al., 1981) and Puri and Dutta (Puri and Dutta, 1990) evaluated structurally similar quinolone esters, highlighting the effectiveness of WR 194,905 and ICI 56,780 (also referred to as WR 197,236), with each compound showing high anti-relapse activity against sporozoite-induced Plasmodium cynomolgi B infections in rhesus monkeys – both completely protective at a daily intramuscular dosage of 15 mg/kg.

While quinolone esters have not ever been promoted for use in treatment of malaria in humans they have proven useful in veterinary medicine for prevention of coccidial infections, especially in chickens. Methylbenzoquate, an alkoxy-quinolone ester, is combined with clopidol, a pyridone derivative, in a synergistic combination to prevent Eimeria infections in chicks (Ryley, 1975). Decoquinate is also combined with clopidol for the purpose of veterinary medicine and combinations of low concentrations of these drugs have been shown to exert a greater inhibition of E. tenella electron transport than expected from the summation of their individual actions (Fry and Williams, 1984, Wang, 1975, Williams, 1997). For this reason we were interested in testing clopidol with our new quinolones for synergistic antimalarial action. Clopidol was previously tested as an antimalarial agent (Markley, et al., 1972) and it has been observed to interact synergistically with atovaquone in vitro (Canfield, et al., 1995). The present studies demonstrate strong synergism between clopidol and a suitably substituted haloalkylquinolone in vitro and are suggestive of the potential for clinically useful combinations of quinolone and pyridone antimalarial agents for prevention or treatment of malaria in humans.

Relevant to the prior work with alkyl and alkyloxy-quinolone antimalarial and anticoccidial agents, the quinolone derivatives described in this paper may prove superior in mammalian systems, i.e., the presence of the CF3 group at the terminus of the alkyl or alkoxy side chain will block or hinder hepatic P450-mediated oxidation at that position. Taken together, the excellent antiplasmodial activity and low cytotoxicity exhibited by these novel quinolones are suggestive of a favorable therapeutic index in vivo and emphasizes the developmental potential of this structural class for clinical use. Possibly of greatest importance is the observation of significant antiplasmodial activity for endochin-like quinolones, i.e., 3-ω-haloalkyl-4(1H)-quinolones, against a clinical isolate of P. falciparum that is highly resistant to atovaquone because these compounds have the potential for use against blood and liver stages of parasite development. Work is underway in this laboratory to continue to optimize the structural features of haloalkyl and haloalkoxy-quinolones for activity against Plasmodium parasites and to evaluate the in vivo efficacy of the most potent derivatives in relevant animal model systems for treatment and prevention of malaria infections.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to extend thanks to Dr. Jose Garcia-Bustos (Tres Cantos, Spain) for discussions that were helpful in the adaptation of BD biosensor plate technology for monitoring oxygen consumption by malarial parasites. We want to acknowledge financial support from the Merit Review Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (grant #AI051509-01A1), and the U.S. Department of Defense PRMRP program (contract #17-03-1-0030). United States patent applications have been filed by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to protect the intellectual property described in this report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature citations

- 1.Ashley E, McGready R, Proux S, Nosten F. Malaria. Travel Medicine and Infectious Diseases. 2006;4:159–173. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashley EA, White NJ. Artemisinin-based combinations. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2005;18:531–536. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000186848.46417.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boggild AK, Parise ME, Lewis LS, Kain KC. Atovaquone-proguanil: report from the CDC expert meeting on malaria chemoprophylaxis (II) American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2007;76:208–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray PG, Mungthin M, Hastings IM, Biagini GA, Saidu DK, Lakshmanan V, Johnson DJ, Hughes RH, Stocks PA, O'Neill PM, Fidock DA, Warhurst DC, Ward SA. PfCRT and the trans-vacuolar proton electrochemical gradient: regulating the access of chloroquine to ferriprotoporphyrin IX. Molecular Microbiology. 2006;62:238–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canfield CJ, Pudney M, Gutteridge WE. Interactions of atovaquone with other antimalarial drugs against Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Experimental Parasitology. 1995;80:373–381. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casey AC. 4(1H)-quinolones. 2. Antimalarial effect of some 2-methyl-3-(1'-alkenyl)-or-3-alkyl-4(1H)-quinolones. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1974;17:255–256. doi: 10.1021/jm00248a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chong CR, Sullivan DJ., Jr Inhibition of heme crystal growth by antimalarials and other compounds: implications for drug discovery. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2003;66:2201–2212. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conrad M, Limpach L. Ueber das γ-Oxychinaldin und dessen Derivate. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 1887;20:944–948. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conrad M, Limpach L. Synthese von Chinolin-Derivaten mittelst Acetessigester. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 1891;24:2990–2992. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidson DE, Jr, Ager AL, Brown JL, Chapple FE, Whitmire RE, Rossan RN. New tissue schizontocidal antimalarial drugs. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1981;59:463–479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards G, Biagini GA. Resisting resistance: dealing with the irrepressible problem of malaria. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2006;61:690–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fry M, Hudson AT, Randall AW, Williams RB. Potent and selective hydroxynaphthoquinone inhibitors of mitochondrial electron transport in Eimeria tenella (Apicomplexa: Coccidia) Biochemical Pharmacology. 1984;33:2115–2122. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fry M, Pudney M. Site of action of the antimalarial hydroxynaphthoquinone, 2-[trans-4- (4'-chlorophenyl) cyclohexyl]-3-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (566C80) Biochemical Pharmacology. 1992;43:1545–1553. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fry M, Williams RB. Effects of decoquinate and clopidol on electron transport in mitochondria of Eimeria tenella (Apicomplexa: Coccidia) Biochemical Pharmacology. 1984;33:229–240. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90480-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gould R, Jacobs W. The synthesis of certain substituted quinolines and 5,6-benzoquinolines. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1939;61:2890–2895. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenwood B. Review: Intermittent preventive treatment--a new approach to the prevention of malaria in children in areas with seasonal malaria transmission. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2006;11:983–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenwood BM, Bojang K, Whitty CJ, Targett GA. Malaria. Lancet. 2005;365:1487–1498. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guarino RD, Dike LE, Haq TA, Rowley JA, Pitner JB, Timmins MR. Method for determining oxygen consumption rates of static cultures from microplate measurements of pericellular dissolved oxygen concentration. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2004;86:775–787. doi: 10.1002/bit.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kikuth W, Mudrow-Reichenow L. Über kausalprophylaktisch bei Vogelmalaria wirksame Substanzen. Zeitschrift für Hygiene und Infektionskrankheiten, medizinische Mikrobiologie. Immunologie und Virologie. 1947;127:151–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korsinczky M, Chen N, Kotecka B, Saul A, Rieckmann K, Cheng Q. Mutations in Plasmodium falciparum cytochrome b that are associated with atovaquone resistance are located at a putative drug-binding site. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2000;44:2100–2108. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2100-2108.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lauer W, Arnold R, Tiffany B, Tinker J. The synthesis of some chloromethoxyquinolines. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1946;68:1268–1269. doi: 10.1021/ja01211a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Limpach L. Bildung der 4-Hydroxylchinaldine aus 3-Arylaminokrotonestern. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 1931;64:969–970. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markley LD, Van Heertum JC, Doorenbos HE. Antimalarial activity of clopidol, 3,5-dichloro-2,6-dimethyl-4-pyridinol, and its esters, carbonates, and sulfonates. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1972;15:1188–1189. doi: 10.1021/jm00281a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meshnick SR. Artemisinin: mechanisms of action, resistance and toxicity. International Journal of Parasitology. 2002;32:1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oduola AM, Milhous WK, Salako LA, Walker O, Desjardins RE. Reduced in-vitro susceptibility to mefloquine in West African isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. Lancet. 1987;2:1304–1305. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pudney M, Yeates C, Pearce J, Jones L, Fry M. Proceedings of the XIIIth International Congress for Tropical Medicine and Malaria. Pattaya, Thailand: Jomtien; 1992. New 4-pyridone antimalarials which potentiate the activity of atovaquone (566C80) p. 149. [Abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puri SK, Dutta GP. Quinoline esters as potential antimalarial drugs: effect on relapses of Plasmodium cynomolgi infections in monkeys. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1990;84:759–760. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90066-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryley JF. Lerbek, a synergistic mixture of methyl benzoquate and clopidol for the prevention of chicken coccidiosis. Parasitology. 1975;70 Part 3:377–384. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000052148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryley JF, Peters W. The antimalarial activity of some quinolone esters. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 1970;64:209–222. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1970.11686683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salzer W, Timmler H, Andersag H. Über einen neuen, gegen Vogelmalaria wirksamen Verbindungstypus. Chemische Berichte. 1948;81:12–19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh A, Rosenthal PJ. Comparison of efficacies of cysteine protease inhibitors against five strains of Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2001;45:949–951. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.949-951.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smilkstein M, Sriwilaijaroen N, Kelly JX, Wilairat P, Riscoe M. Simple and inexpensive fluorescence-based technique for high-throughput antimalarial drug screening. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2004;48:1803–1806. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1803-1806.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snow RW, Guerra CA, Noor AM, Myint HY, Hay SI. The global distribution of clinical episodes of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2005;434:214–217. doi: 10.1038/nature03342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Srivastava IK, Morrisey JM, Darrouzet E, Daldal F, Vaidya AB. Resistance mutations reveal the atovaquone-binding domain of cytochrome b in malaria parasites. Molecular Microbiology. 1999;33:704–711. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trager W, Jensen JB. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang CC. Studies of the mitochondria from Eimeria tenella and inhibition of the electron transport by quinolone coccidiostats. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1975;396:210–219. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(75)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.White NJ. Antimalarial drug resistance. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113:1084–1092. doi: 10.1172/JCI21682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.White NJ, Nosten F, Looareesuwan S, Watkins WM, Marsh K, Snow RW, Kokwaro G, Ouma J, Hien TT, Molyneux ME, Taylor TE, Newbold CI, Ruebush TK, 2nd, Danis M, Greenwood BM, Anderson RM, Olliaro P. Averting a malaria disaster. Lancet. 1999;353:1965–1967. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07367-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams RB. The mode of action of anticoccidial quinolones (6-decyloxy-4-hydroxyquinoline-3-carboxylates) in chickens. International Journal of Parasitology. 1997;27:101–111. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(96)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winstanley P, Ward S. Malaria chemotherapy. Advances in Parasitology. 2006;61:47–76. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)61002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Winter RW, Kelly JX, Smilkstein MJ, Dodean R, Bagby GC, Rathbun RK, Levin JI, Hinrichs D, Riscoe MK. Evaluation and lead optimization of anti-malarial acridones. Experimental Parasitology. 2006;114:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]