Summary

Loss of appetite and cachexia is an obstacle in the treatment of chronic infection and cancer. Proinflammatory cytokines released from activated immune cells and acting in the central nervous system (CNS) are prime candidates for mediating these metabolic changes, potentially affecting both energy intake as well as energy expenditure. The effect of intravenous administration of two proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1β (15 µg/kg) and TNF-α(10 µg/kg) on food and water intake, locomotor activity, oxygen consumption (VO2), and respiratory exchange ratio (RER) was evaluated. The two cytokines elicited a comparable decrease in food intake and activated similar numbers of cells in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH), a region that plays a critical role in the regulation of appetite and metabolism (determined via expression of the immediate early gene, c-fos). However, only IL-1β reduced locomotion and RER, and increased VO2, while TNF-α was without effect. To examine the role of the melanocortins in mediating IL-1β- induced metabolic changes, animals were pretreated centrally with a melanocortin receptor antagonist, HS014. Pretreatment with HS014 blocked the effect of IL-1β on food intake and RER at later time points (beyond 8hr post injection), as well as the hypoactivity and increased metabolic rate. Further, HS014 blocked the induction of Fos-ir in the PVH. These data highlight the importance of the melanocortin system, particularly within the PVH, in mediating a broad range of metabolic responses to IL-1β.

Keywords: IL-1, HS014, sickness behavior, Fos, paraventricular

Introduction

Loss of appetite and cachexia, defined as increased metabolism of both skeletal muscle and adipose tissue (Tisdale, 1997), are symptoms that often accompany chronic infection or inflammation. Present in up to 63% of all cancer patients (Laviano et al., 2005), as well as other chronic conditions including AIDS, heart failure, tuberculosis and renal failure (DeBoer and Marks, 2006), cachexia can significantly affect quality of life (Fearon et al., 2006) and response to therapy (Dewys et al., 1980). Current drug therapies include progestagens, anti-cytokine and anti-inflammatory drugs, and nutritional supplementation, but the efficacy of these approaches is limited at best (Boddaert et al., 2006). Illness-associated cachexia/anorexia involves problems with both energy intake and energy expenditure, in part mediated at the level of the central nervous system (CNS). Before more effective therapies for illness-associated anorexia and cachexia can be developed, a clearer understanding is needed of the physiological systems, and the CNS mediators in particular, that underlie different aspects of this complex metabolic dysregulation.

Proinflammatory cytokines, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) are primary mediators of the loss of appetite and metabolic dysregulation seen in cancer, inflammation and infection, a relationship well documented in a recent review (DeBoer and Marks, 2006). During illness and infection, circulating levels of the proinflammatory cytokines, IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α, are dramatically elevated. When administered centrally, each of these cytokines can independently reduce food intake (Plata-Salaman, 1998). Experiments with mice genetically modified to lack either receptors or ligands of these systems have implicated cytokines in mediating this anorexia, as well as highlighting a redundancy within the system, such that the absence of a single cytokine or receptor is often compensated for by other cytokines (Bluthe et al., 2000; Leon et al., 1998). Repeated administration of cytokines can mimic the metabolic effects independent of changes in food intake (Ling et al., 1997), implicating a role for cytokines in multiple aspects of the cachexia syndrome. Importantly, a number of potentially beneficial immunotherapies that use long-term administration of cytokines have proven impractical due to these types of CNS side effects (Veltri and Smith, 1996). The majority of published studies have used food intake and/or body weight change as singular endpoints, using various tumor models or peripheral or central injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS, a component of gram negative bacteria) or single cytokines. This manuscript describes the simultaneous measurement of numerous metabolic responses to evaluate both energy intake and energy expenditure (food and water intake, locomotor activity, oxygen consumption and respiratory exchange ratio (RER)). Further, we have chosen to examine single cytokine administration (IL-1β and TNF-α, as IL-6 may be less important in mediating immune-associated metabolic changes (Swiergiel and Dunn, 2006), in an effort to determine which metabolic parameters are affected by each cytokine.

Recruitment of the melanocortin system may be of particular importance downstream of cytokine signaling. Of the five known melanocortin receptors, MC3R and MC4R are expressed primarily in the brain with partially overlapping distribution (Mountjoy et al., 1994; Roselli-Rehfuss et al., 1993), with MC4R displaying a more widespread expression pattern (Mountjoy et al., 1994). There is both an endogenous agonist (α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH), derived from the pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) precursor) and antagonist (agouti-related protein, AgRP) for the melanocortin receptors. These two neuropeptides are expressed in separate neuronal populations within the arcuate nucleus and both cell types express MC3R, suggesting either auto-regulation and/or cross talk between these two neuronal populations (Bagnol et al., 1999). One of the more intensely studied aspects of melanocortin biology is their involvement in the regulation of both food intake and energy metabolism (Forbes et al., 2001); α-MSH inhibits food intake (Ludwig et al., 1998), while AgRP is a potent stimulator of food intake (Rossi et al., 1998). With regard to receptors, MC3R knockout mice demonstrate increased adiposity and enhanced feed efficiency (Chen et al., 2000), while MC4R knockout mice are hyperphagic and obese (Huszar et al., 1997).

Importantly, this system, and MC4R in particular, has been implicated in mediating illness-induced anorexia. We have shown previously that IL-1 given peripherally activates POMC expressing neurons, in both the arcuate proper, and in laterally contiguous aspects of the hypothalamus (Reyes and Sawchenko, 2002). Central administration of either mixed or selective MC3R or MC4R antagonists blocked the anorexia associated with IL-1 (Joppa et al., 2005; Lawrence and Rothwell, 2001), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Huang et al., 1999) or a prostate tumor (Wisse et al., 2001). Even more compelling, a MC4R selective antagonist attenuated the anorexia and enhanced the gain of lean body mass and fat in a mouse cancer model (Markison et al., 2005), implicating MC4R directly in cancer cachexia. Additionally, MC4R deficient mice are resistant to both LPS and cancer-induced anorexia (Marks et al., 2001). Collectively, these studies support the importance of the melanocortin system in mediating aspects of the metabolic responses to immune activation. The current studies are unique in their comparison of an extensive set of metabolic parameters collected simultaneously and non-invasively in response to select proinflammatory cytokines. Because cancer cachexia involves global metabolic dysregulation, multiple physiological systems may be affected (e.g. food intake as well as energy expenditure). Moreover, we have identified an important role for melanocortin signaling in mediating the metabolic responses to IL-1β, and identified the PVH as a potential site for this interaction.

Methods

Animals and surgical procedures

Adult male Sprague Dawley rats (250–300gm at the start of experimentation) were housed in a colony room on a 12 hr light/dark cycle (lights on at 7:00AM), with ad libitum access to food (Rodent Diet 5001, Lab Diet) and water. Jugular vein catheters were surgically implanted by the vendor (Taconic). Catheters were filled with heparinzied saline and exteriorized at an interscapular position. Three to five days after arrival into our animal facility, animals were implanted with an intracerebroventricular cannula (ICV) targeting the right lateral ventricle (coordinates from Bregma: −0.7 ML, −1.4 AP, −3.6 DV) under isoflurane anesthesia. Animals received buprenorphine (.05 mg/kg) every 12 hr for 36 hr post-surgery. Guide cannulae were fitted with a dummy cannula, and animals were allowed at least one week to recover prior to testing. Animals in Study 1 did not receive an ICV cannula. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Scripps Florida.

Metabolic measurements

Animals were tested in the Comprehensive Lab Animal Monitoring System (CLAMS, Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH). This system continuously and simultaneously monitors food and water intake, indirect calorimetry, and x- and z-axis activity. Animals had unrestricted access to powdered chow through a feeder located in the middle of the cage floor. Animals were acclimated to the system prior to testing. Injections (both ICV and IV) occurred between 6 and 6:30pm, with lights off at 7pm.

Tissue processing, histology and immunohistochemistry

Animals were deeply anesthetized with chloral hydrate (350 mg/kg, i.p.) and perfused via the ascending aorta with saline (RT) followed by ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in a 0.1% borate buffer at pH 9.5. Brains were postfixed for 16hr and cryoprotected overnight in 10% sucrose in 0.1M phosphate buffer. Six series of 30-µM-thick frozen sections were cut using a sliding microtome, collected in cold ethylene glycol-based cryoprotectant and stored at −20° C until processing.

Primary antisera was rabbit polyclonal antiserum directed against the N-terminal region of the human c-Fos protein (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC-52, 1:10K). Specificity controls included pretreatment with the blocking peptide (SC-52P) and incubation without the primary antibody. Endogenous peroxidase activity was neutralized by treating tissue for 10 min with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide, followed by 8 min in 1% sodium borohydride to reduce free aldehydes. Cells were permeabilized with PBS-0.2% Triton X-100 and incubated with primary antibody plus 4% normal goat serum overnight at 4°C. Localization was performed using a conventional avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase method. Differences in the relative abundance of Fos were estimated by simple cell counting. Counts of stained neurons were made in regularly spaced series of sections in cell groups of interest defined on the basis of adjoining Nissl-stained sections.

Study 1

To determine the effect of IL-1β and TNF-α on the activation of neurons in the CNS, animals were injected with IL-1β (R & D Systems, 15 µg/kg, IV) or TNF-α (R & D Systems, 10 µg/kg, IV) and perfused 2 hr later. Doses were chosen that resulted in a mild anorexia (~25% reduction in food intake in 24 hr) and full recovery within 48 hrs. The number of Fos-ir cells was counted and analyzed using ANOVA, with a posthoc t-test.

Study 2

This study used a repeated measures design, such that each animal received both an injection of cytokine and vehicle, and the order of those injections was counterbalanced (n=8 rats/group). The two cytokines were compared in separate groups of animals. To compare metabolic responses to these two cytokines, animals were removed from the home cage and placed in the CLAMS cage (in the same housing room) at 2pm. Animals were injected with IL-1β (R & D Systems, 15 µg/kg, IV) or vehicle. A separate group of animals were injected with TNF-α (R & D Systems, 10 µg/kg, IV) or vehicle. All injections occurred between 6–6:30pm. Animals remained in the CLAMS system overnight, and were returned to the home cage at approximately 3pm the next day. Data were analyzed using a two-way, repeated measures ANOVA (drug × time).

Study 3

Animals were removed from the home cage and placed in the CLAMS cage (in the same housing room) at 2pm. Animals (n=4–5/group) were injected with HS014 (Bachem, 2 µg/rat, ICV) or saline (ICV) followed 15 min later by an IV injection of IL-1β (R & D Systems, 15 µg/kg, IV) or vehicle (0.1% BSA). A range of doses taken from the literature (1–5 µg/rat) were tested in a separate group of rats and the lowest dose that had no effect on food intake or energy expenditure was selected for use in these studies. All injections occurred between 6–6:30pm. Animals remained in the CLAMS system overnight, and were returned to the home cage at approximately 3pm the next day. Data were analyzed using a two-way, repeated measures ANOVA (drug × time).

Study 4

Study 1: To determine the effect of pretreatment with HS014 on IL-1β-induced Fos-ir, animals (n=2–4/group) were injected with HS014 (Bachem, 2 µg/rat, ICV) or saline (ICV) followed 15 min later by an IV injection of IL-1β (R & D Systems, 15 µg/kg, IV) or vehicle (0.1% BSA). Animals were perfused 2 hr later.

Results

Study 1

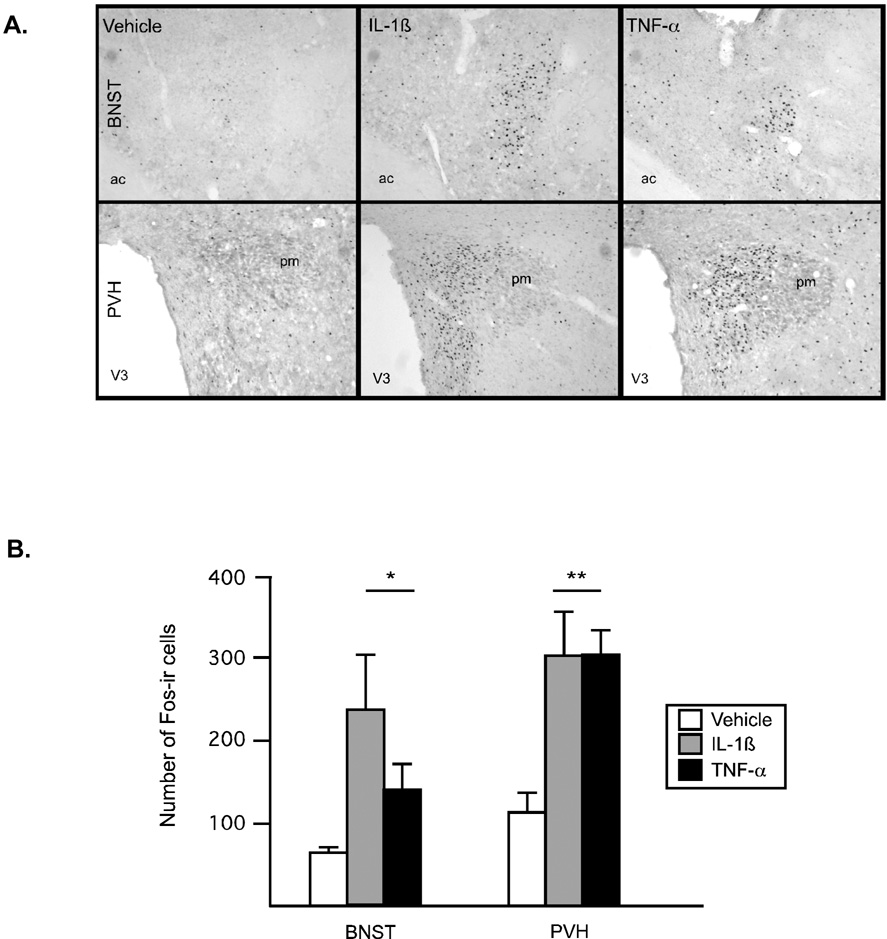

Expression of the immediate early gene, c-fos, in select forebrain regions was used to identify comparable doses of the two cytokines. Overall, the two cytokines elicited distinct, but partially overlapping, patterns of neuronal activation. Little to no Fos-ir was apparent in animals injected with saline, aside from known regions of constitutive Fos expression (e.g., PVT). In response to injection of proinflammatory cytokines, there was an increase in Fos-ir in select brain regions. Following IV administration of IL-1β, significant activation was observed in the expected pattern (including significant expression in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH), central amygdaloid nucleus, lateral parabrachial nuclei, nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and ventrolateral medulla, e.g.,(Ericsson et al., 1994)). TNF-α resulted in a less extensive pattern of activation, with the most robust expression of Fos observed in lateral septum, organum vasculum of the lamina terminallis (OVLT), PVH, supraoptic nucleus (SON), NTS and area postrema (AP), in line with a previous report (Tolchard et al., 1996). Scattered positive cells were also observed in the amygdala, as well as a few scattered cells within the arcuate nucleus (ARH). Activational responses were quantified in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and PVH (Figure 1A and B). In BNST, both cytokines activated a significant number of cells above that seen in saline-injected controls (F(2,9)=4.1, p<.05) and these cells were localized mainly to the lateral portion of the nucleus. Overall these responses appeared somewhat less robust in TNF-α injected animals. In response to either cytokine, Fos-ir in the PVH was significantly elevated above control animals (F(2,9)=7.12, p<.01) and the observed pattern was indistinguishable between the two cytokines, showing a preferential activation of parvocellular neurons. IL-1β resulted in activation of a small, but statistically reliable, number of arcuate neurons (F(2,9)=4.8, p<.04), an effect absent in response to TNF-α(data not shown).

Figure 1.

Photos (A) and quantification (B) of Fos-immunoreactive cells in the brain in response to intravenous cytokine administration. (A) A significant and comparable induction of Fos-ir was apparent in BNST and PVH two hours after injection of IL-1β or TNF-α. (B) Fos-ir cells were counted and results are displayed in a bar graph (open bar: saline, gray bar: IL-1β (15µg/kg), black bar: TNF-α (10 µg/kg)). *p<.05, different from saline, **p<.01, different from saline. N=3 rats/group.

Study 2. Metabolic response to IL-1β and TNF-α

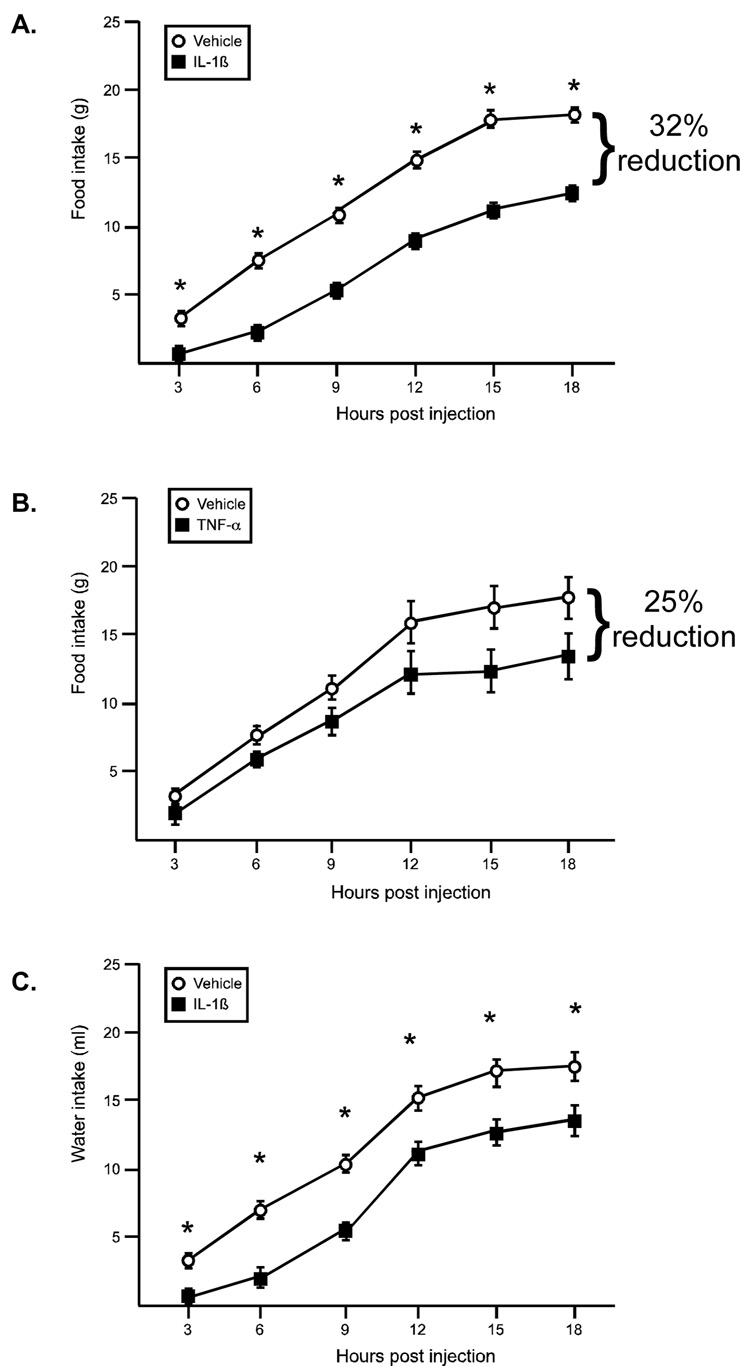

Food and water intake

Both IL-1β and TNF-α resulted in a reduction in food intake, albeit with different timing (Figure 2A and 2B). For IL-1β there was a significant effect of the drug (F(1,78)=142.1, p<.0001) and time (F(6,78)=5.64, p<.0001), such that IL-1β treated animals ate significantly less food throughout the entire observation period, and food intake increased over time. The reduction in food intake in response to TNF-α was slower to emerge (~12 hr post injection). There was a significant effect for time (F(5,70)=91.4, p<.0001), while the drug effect just missed significance (F(1,70)=3.93, p=.06). At 18 hrs postinjection, IL-1β treated animals ate 32% less than controls, while TNF-α treated animals ate 25% less than controls. Water intake was also significantly reduced in response to IL-1β, with a significant effect of the drug (F(1,84)=15.9, p<.0013) and time (F(6,84)=1.21, p<.0001, Figure 2C). There was no difference in water intake in animals treated with TNF-α compared to their vehicle controls (data not shown).

Figure 2.

IL-1β and TNF-α effects on food and water intake. (A). IL-1β significantly decreased food intake; * indicates a main effect for drug, p<.0001 (B) TNF-α decreases food intake only at later time points, (trend for drug main effect, p=.06) (C) IL-1β significantly decreases water intake. * indicates a main effect for drug, p<.013 (open symbol: vehicle, black symbol: cytokine) n=8 rats/group

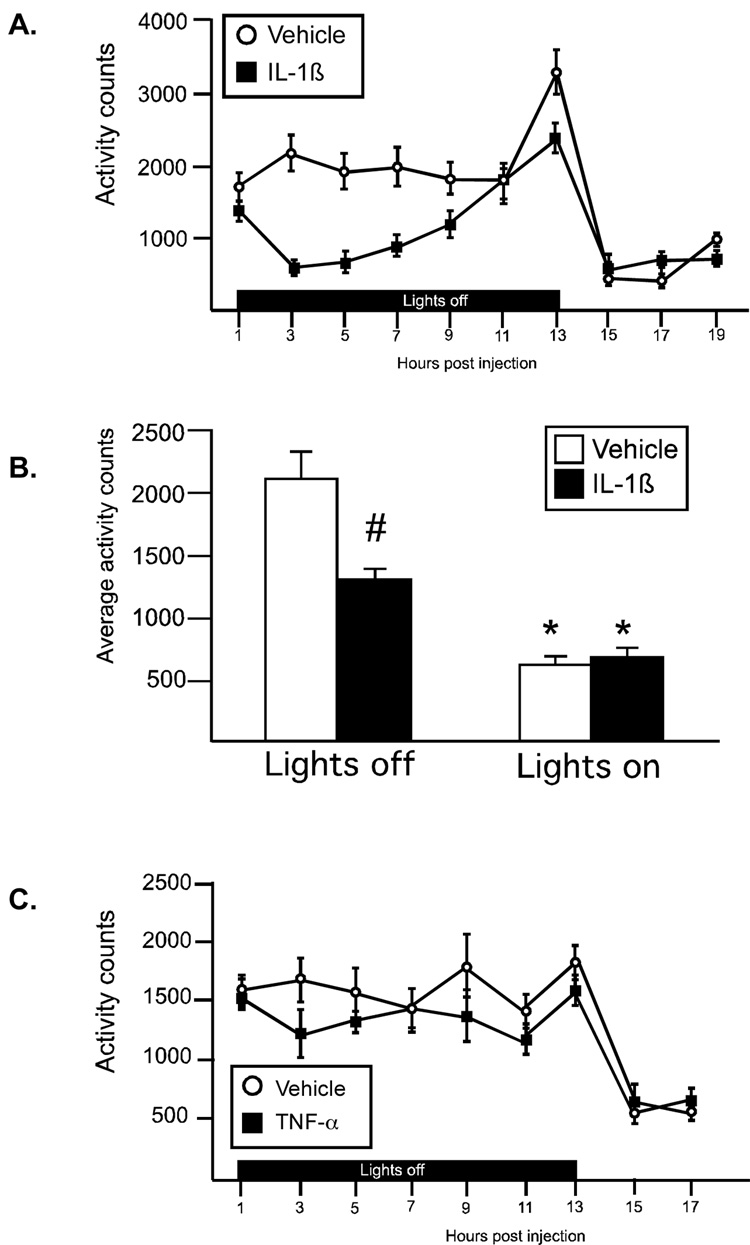

Activity

IL-1β resulted in a significant reduction in activity that was most pronounced at 3–9 hr after the injection (Figure 3A, 3B. There was a significant drug × time interaction (F(8,112)=2.3, p<.02), as well as significant main effect for both drug (F(1,112)=20.6, p<.0005) and time (F(8,112)=8.76, p<.0001). All animals were significantly less active after the lights came on. Average activity counts during lights off and lights on time periods were compared using a 2-way ANOVA (Figure 3B), and a significant interaction (F(1,14)=19.0, p<.0007) was identified. IL-1β treated animals were significantly less active compared to controls during the lights off period, but did not differ from controls during the lights on time period (Figure 3B; p<.001, Bonferroni corrected α=0.05/2=.025). There was no significant effect on activity levels in animals treated with TNF-α (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

IL-1β and TNF-α effects on activity. (A) IL-1β significantly decreased locomotor activity during lights off. (B) Average activity counts during lights off and lights on. Both saline and IL-1β treated animals were less active during lights on, *p<.0001 (main effect). IL-1β treated animals were significantly less active than vehicle controls during lights off; #p<.001, (Bonferroni corrected α .05/2=.025) (C) TNF-α did not affect locomotor responses. (open symbol: vehicle, black symbol: cytokine) n=8 rats/group

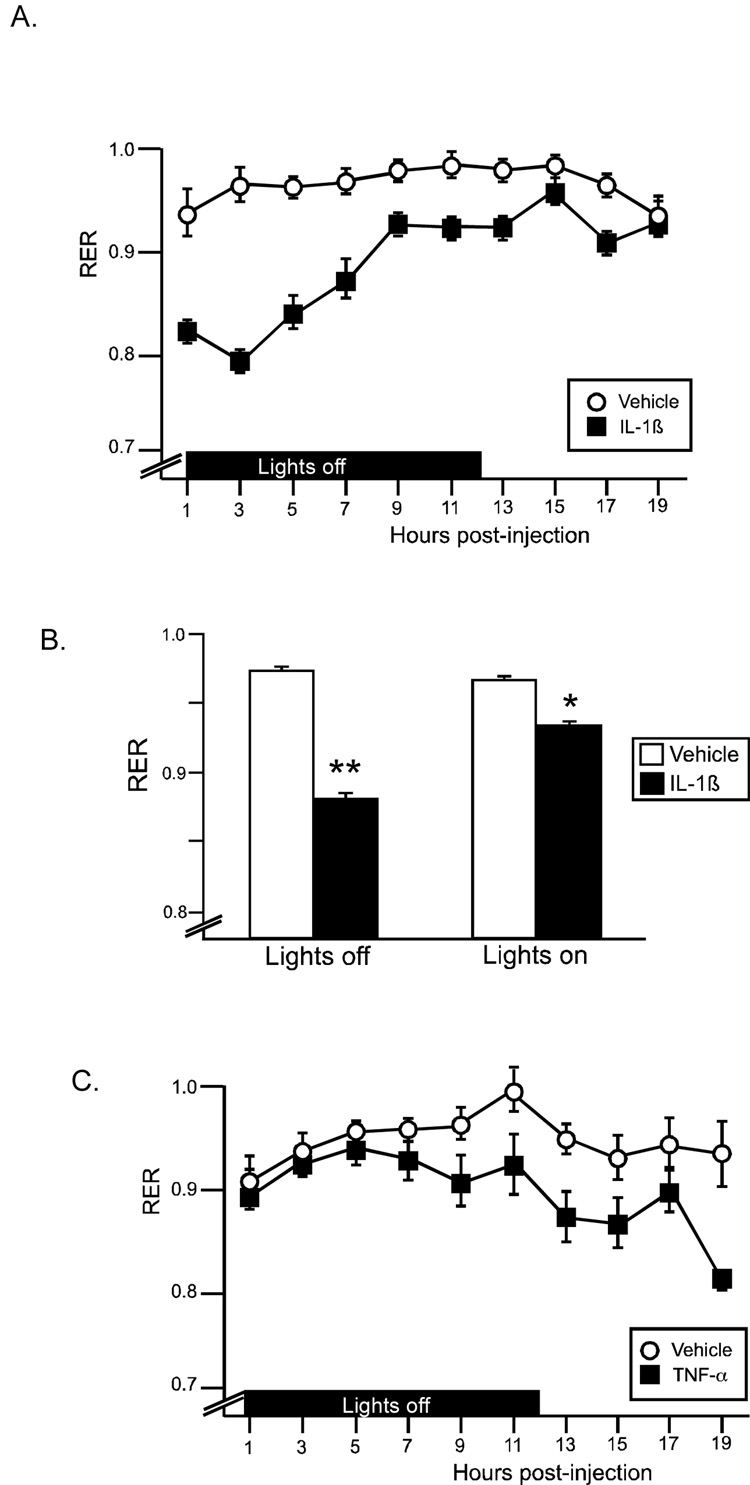

RER and metabolic rate

Respiratory exchange ratio (RER; the ratio of VCO2/VO2) provides information on energy substrate utilization. A theoretical limit of 1 indicates the utilization of pure carbohydrates for fuel, while a value of 0.7 refers to pure fat metabolism. For at least 14 hrs post-injection, RER was significantly reduced in response to IL-1β injection, particularly in the initial 7 hrs (Figure 4A). There was a significant drug × time interaction (F(10,140)=11.3, p<.0001), as well as significant main effects for drug (F(1,140)=63.6, p<.0001) and time (F(10,140)=16.3, p<.0001). Average RER during lights off and lights on time periods were compared using a 2-way ANOVA (Figure 4B), and a significant interaction (F(1,14)=43.6, p<.0001) was identified. IL-1β resulted in a lowered average RER value during both the lights off and lights on periods (Figure 4B; p<.001, p<.01 (Bonferroni corrected α=0.05/2=.025)). TNF-α resulted in a slight decrease in RER, which was observed beginning at 9 hr post injection. There was a significant effect for time (F(8,112)=5.5, p<.0001), while the drug effect just missed significance (F(1,112)=4.1, p=.06). Neither IL-1β nor TNF-α resulted in significant increases in oxygen consumption.

Figure 4.

IL-1β and TNF-α effects on respiratory exchange ratio (RER). (A) IL-1β decreases RER acutely, with a gradual return to control levels by 19hr postinjection. (B) Average RER during lights off and lights on. IL-1β treated animals had a significantly lower RER than vehicle controls during both timeperiods; **p<.001, *p<.01 (Bonferroni corrected α .05/2=.025) (C) TNF-α results in a nonsignificant reduction in RER at the later time points. (open symbol: vehicle, black symbol: cytokine) n=8 rats/group

Study 3. Effect of HS014 on metabolic responses to IL-1β

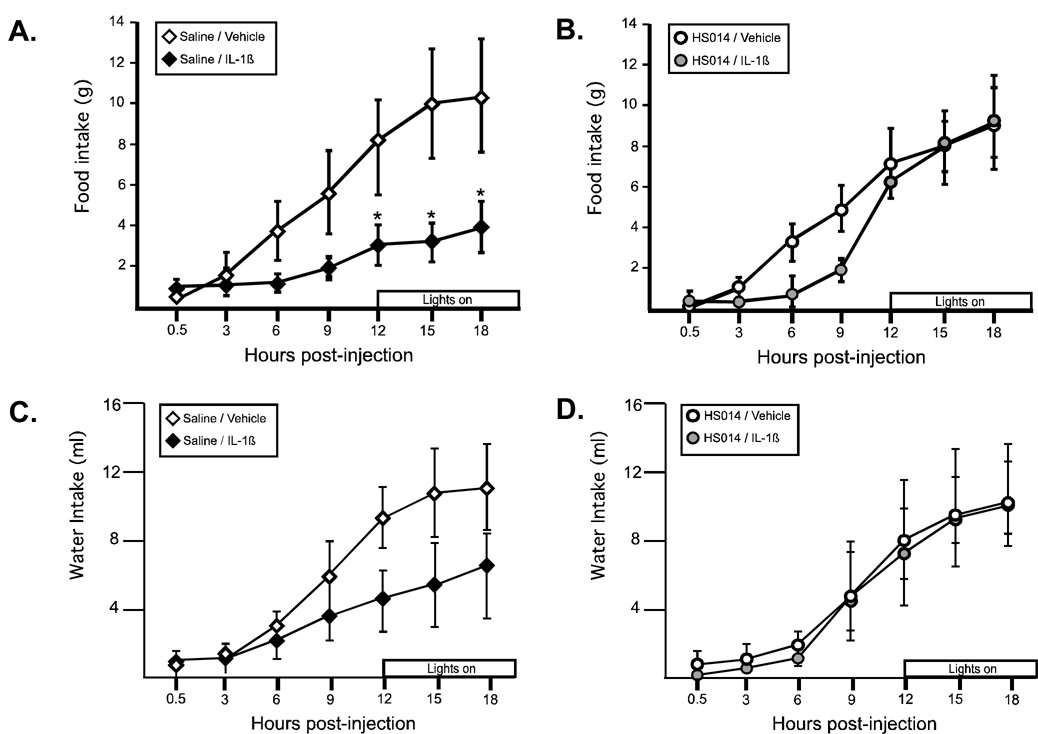

Food intake

Because IL-1β had the most pronounced effect on food intake, activity and RER, we investigated the role of melanocortin receptor blockade in mediating these metabolic changes. In response to IL-1β, animals demonstrated a significant decrease in food intake (Figure 5A). There was a significant effect of IV treatment (vehicle vs. IL 1β; F (1,36)=6.9, p<.04). IL-1β treated animals ate less than controls beginning approximately 4 hr after the injection, a difference which was significant at all timepoints after 12 hrs postinjection (p<.0001; Bonferroni corrected α=0.05/7=.007).) Central blockade of the MC4R prior to IL-1β administration significantly attenuated the observed anorexia, primarily in the later phase of the response (Figure 5B), such that there was no longer a significant effect of IV treatment (F(1,48)=0.58, n.s.). Animals pretreated with HS014 followed by saline IV did not differ from control animals (saline/vehicle) at any time point. Total water intake (Figure 5C and 5D) did not differ between the groups, although there was a nonsignificant reduction in the total amount of water consumed following injection of IL-1β that was not observed in animals pretreated with HS014 (water consumed (ml) 18 hr post-injection; Sal/Veh: 11.1±2.6, Sal/IL1: 6.9±2.9, HS014/Sal: 10.6±2.6, HS014/IL-1: 11.7±1.4), Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Melanocortin receptor blockade with HS014 ameliorated the IL-1β-induced reduction in food intake. (A) For animals pretreated with saline, IL-1β resulted in a significant reduction in food intake (black diamonds) *p<.0001; Bonferroni corrected α .05/7=.007). (B) For animals pretreated with HS014, there was no significant difference in food intake (gray circles). Control animals (open symbols) did not differ from one another. (C and D) Water intake followed a similar pattern, but the differences were not statistically reliable. n=4–5 rats/group

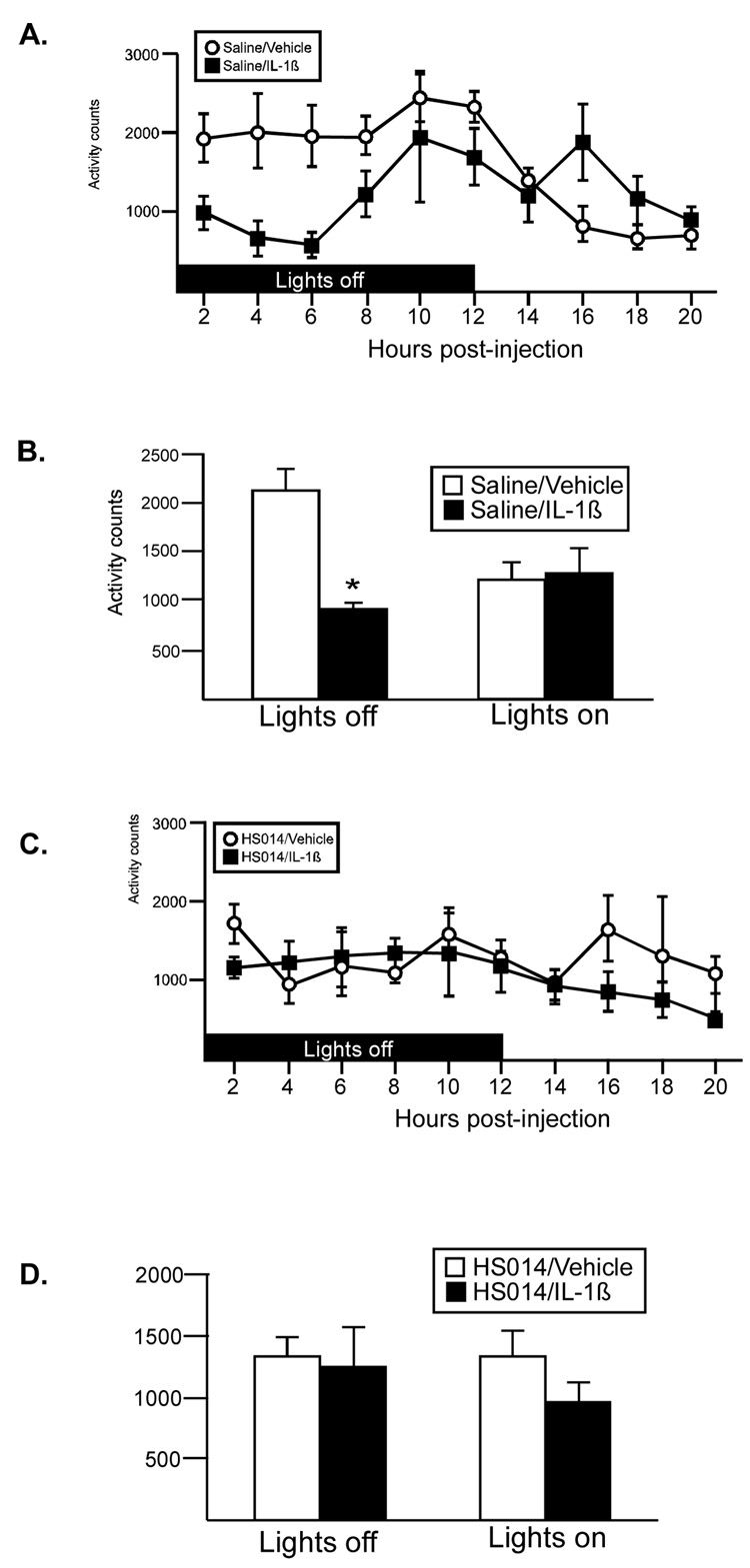

Activity

Figure 6A shows animals pretreated with saline ICV. In response to IL-1β injection, animals were significantly less active in the 6 hrs post injection (similar to Study 2, Figure 3A) (two way ANOVA: drug × time interaction (1, 16=12.71, p<.0026)). Average activity during lights off and lights on time periods were compared using a 2-way ANOVA (Figure 6B), and a significant interaction (F(1,8)=18.4, p<.003) was identified. IL-1β treated animals were significantly less active compared to controls during the lights off period, but did not differ from controls during the lights on time period (Figure 3B; p<.01, Bonferroni corrected α=0.05/2=.025). When animals were pretreated with the melanocortin receptor antagonist, the hypoactivity response was blocked (Figure 6C, 6D).

Figure 6.

The effect of melanocortin receptor blockade with HS014 on IL-1β-induced hypoactivity. (A) Administration of IL-1β resulted in a significant reduction in activity during lights off. (B) Average activity counts during lights off and lights on. Sal/IL-1β treated animals were less active than vehicle controls during lights off ; *p<.01 (Bonferroni corrected α .05/2=.025) (C) Pretreatment of animals with HS014 abolished this response. (D) Average activity counts during lights off and lights on for animals pretreated with HS014. n=4–5 rats/group

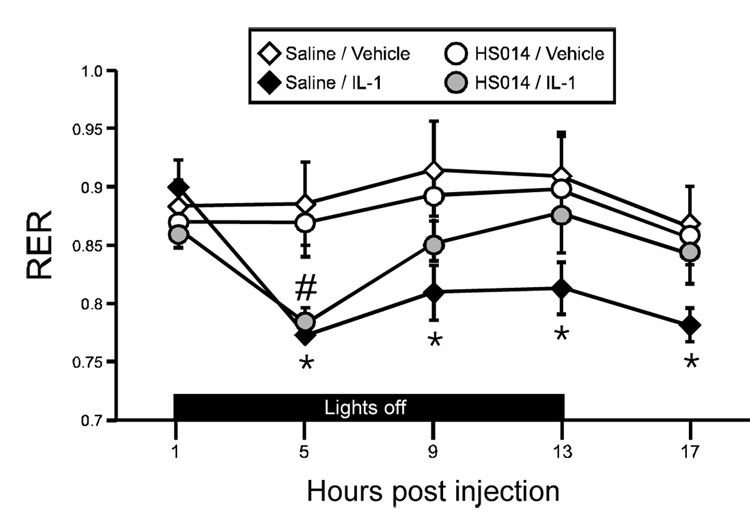

RER

At four hrs post-injection, RER was significantly reduced in response to IL-1β injection, regardless of the ICV pretreatment (Figure 7; p<.0005 for saline pretreated animals, p<.002 for HS014 treated animals, Bonferroni corrected α.05/8=.006), indicating a significant shift in the energy substrate utilization (away from carbohydrates/protein toward an increase in the burning of fat, as seen in Study 2, Figure 4A). Two-way ANOVA identified a significant interaction (F(12,64)=2.05, p<.04). In animals pretreated with saline, RER remained significantly reduced in IL-1β- treated animals throughout the testing period (p<.0005, Sal/IL-1β versus Sal/Vehicle, Bonferroni corrected α=0.05/8=.006). However, for animals pretreated with HS014, RER returned to control levels within 7 hrs postinjection. Melanocortin blockade alone had no effect on RER.

Figure 7.

Melanocortin receptor blockade with HS014 ameliorated the IL-1β-induced reduction in RER. Administration of IL-1β resulted in a significant reduction in RER (black diamonds and gray circles). Pretreatment of animals with HS014 ICV resulted in a recovery to control values by 9 hr postinjection (gray circles). Control animals (open symbols) did not differ from one another. # p<.002 HS014/IL-1β versus HS014/Vehicle. *p<.0005, Sal/IL-1β versus Sal/Vehicle (Bonferroni corrected α .05/8=.006). n=4–5 rats/group

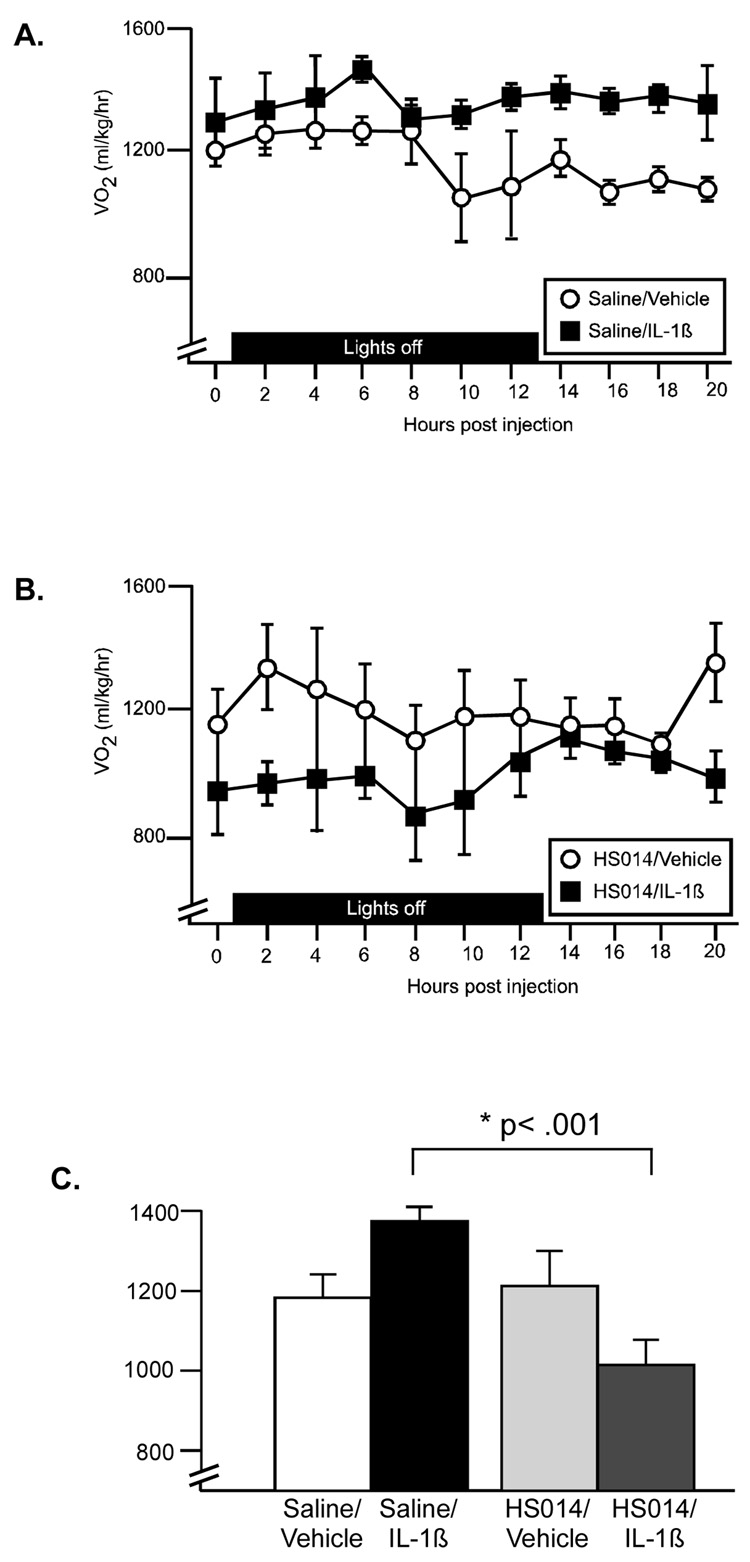

Metabolic rate

In animals pretreated with saline ICV, there was a significant increase in oxygen consumption above control values beginning approximately 10 hrs postinjection (Figure 8A; main effect for drug (F(1,16)=14.4, p<.002). Pretreatment of animals with HS014 ICV reversed this effect. In animals pretreated with HS014, all values for the cytokine injected animals were below control values at all time points (F(1,14)=5.75, p=.03) (Figure 8B). Importantly, the control animals (Sal/Veh and HS014/Veh) did not differ in their metabolic rates at any time point. The average VO2 values across the entire test period are represented in Figure 8C. Two-way ANOVA reveals a significant interaction between (F(1,15)=11.79, p<.004), such that in saline-pretreated animals metabolic rate is increased, while in HS014-preated animals metabolic rate is decreased.

Figure 8.

The effect of melanocortin blockade on metabolic rate (oxygen consumption). (A). IL-1β resulted in a significant increase in metabolic rate, particularly in the later time points (beyond 8 hr postinjection). (B). Pretreatment of animals with HS014 reversed this effect. (open symbol: saline, black symbol: cytokine). (C) Average VO2 during 20 hr postinjection. *p<.001 Sal/IL-1β significantly greater than HS014/IL01β (Bonferroni corrected α .05/3=.016). n=4–5 rats/group

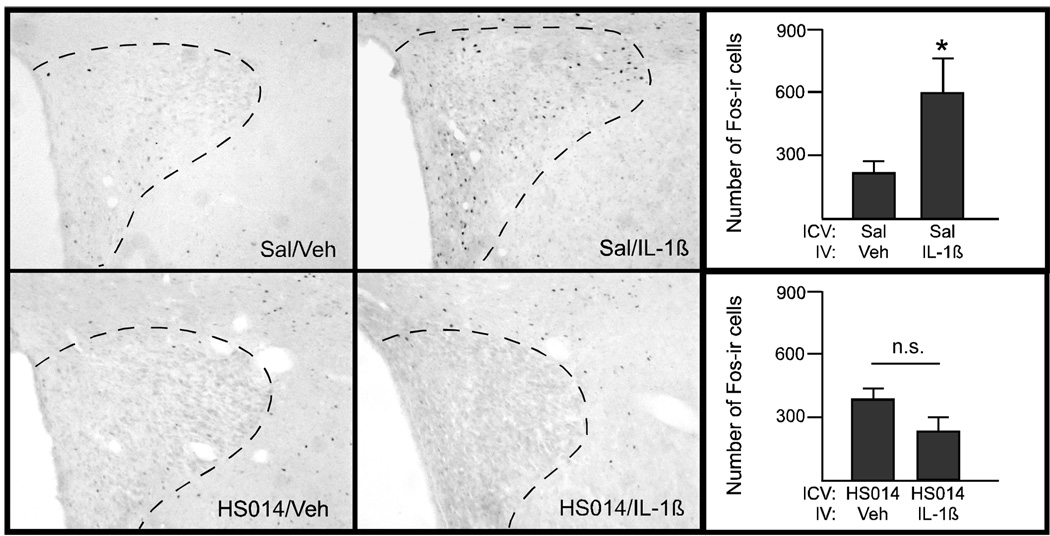

Study 4: Effect of HS014 pretreatment on IL-1β-induced Fos-ir

In animals pretreated with saline ICV, administration of IL-1β activated neurons within the PVH in a pattern similar to that seen in Study 1 (see representative image in Figure 9, top row). In animals injected peripherally with the vehicle solution, the two control groups did not differ (e.g., those pretreated with HS014 centrally did not differ from those injected with saline ICV.) Notably, pretreatment with HS014 blocked the IL-1β-induced Fos response in the PVH (Figure 9, bottom row). The number of Fos-ir+ cells was also quantified (Figure 9, right panels). Fos-ir+ cells were also counted in the NTS, and there were no significant differences between any of the groups (data not shown).

Figure 9.

The effect of HS014 on Fos-ir+ cells in the PVH. Photographs and quantification of Fos-immunoreactive cells in the PVH of animals treated with saline ICV (top row) or HS014 (bottom row). A significant induction of Fos-ir was apparent in PVH two hours after injection of IL-1β in animals pretreated with saline; *p<.05 (t-test). This response is eliminated in animals pretreated with HS014. n=2–4 animals/group.

Discussion

These data both confirm and extend our current understanding of the metabolic responses to peripheral injections of IL-1β and TNF-α. Intravenous administration of relatively low doses of cytokines was used to mimic a mild, sub-septic immune response (e.g., full recovery of metabolic response to baseline by 24hrs). IL-1β resulted in a decrease in food and water intake, a significant reduction in activity, as well as a significant decrease in RER. This is in contrast to TNF-α, which affected only food intake and to a minor extent, RER.

The comparison of the physiological responses to IL-1β and TNF-α reveled notable differences between the two proinflammatory cytokines. Reduction in food intake was used to titrate the doses, as this response has been described previously for both cytokines (Bodnar et al., 1989; Reyes and Sawchenko, 2002). The overall magnitude of the resultant anorexia was comparable (32% vs 25% reduction in food intake at 18hr for IL-1β and TNF-α, respectively), albeit with a differential time course. In areas expressing Fos-ir in response to both IL-1 and TNF-α (e.g., PVN and BNST, (Ericsson et al., 1994; Hayley et al., 2001)), the numbers of Fos-ir cells did not differ. These are regions known to be responsive to stressors and/or metabolic challenges. IL-1β alone induced Fos-ir in the arcuate, another brain region critical in the regulation of food intake. This may be partially explained by the expression of IL-1 receptor (Ericsson et al., 1995) and the absence of the TNF receptors (p55 and p75 (Nadeau and Rivest, 1999)) in the arcuate nucleus. Whether higher doses of TNF-α would have resulted in additional effects on the recorded metabolic parameters is yet to be determined, and may be supported by the data showing that the effective dose to lower consumption of a palatable liquid was 10-fold greater for TNF-α compared to IL-1β (Brebner et al., 2000). That being said, we intentionally chose doses of IL-1β and TNF-α that resulted in comparable levels of anorexia and comparable levels of neuronal activation in the PVH (See Fig 1), a brain region critical for the regulation of appetite and metabolism (Sawchenko, 1998). This allowed us to examine some of the less well-studied parameters (VO2, RER) using known effective doses. The time course of the effects differed, such that the anorexia and decrease in RER in response to TNF-α had a much later onset when compared to the responses to IL-1β. TNF-α had no statistically reliable effects on oxygen consumption, however the average oxygen consumption of TNF-α injected animals was above that of controls for the entire time period of 6–12 hrs post-injection. Hence, at doses that resulted in comparable anorexia and activational responses (Fos-ir) in PVH, TNF-α affected fewer metabolic parameters.

Because TNF-α had only a modest effect on these metabolic parameters, only IL-1β was used in combination with the melanocortin antagonist, HS014. This cyclic MSH analog displays a 10-fold greater potency for MC4R over MC3R, as compared to a similar commonly used antagonist, SHU9119. Therefore, these results do not definitively assess the respective contribution of each receptor subtype. Importantly, at the low dose of HS014 employed in the current studies, there were no effects of the antagonist alone (i.e. HS014/vehicle treated animals did not differ from saline/vehicle treated animals on most of the metabolic parameters).

Anorexia is a typical response to peripheral IL-1β administration, as shown here and in previous reports (Joppa et al., 2005; Reyes and Sawchenko, 2002; Wisse et al., 2006), and melanocortin blockade affected the later phase of this response. Pretreatment with the melanocortin receptor antagonist had no effect on the early response; however, after 12 hrs these animals showed a rapid recovery in food intake to the level seen in both control groups. This finding suggests that activity on the melanocortin receptors may not be important for the initiation of the anorexia, but clearly plays a role in the maintenance of the reduced food intake. A recent paper examining IL-1β-induced anorexia found that blockade of melanocortin receptors could attenuate IL-1β anorexia, but that the time course and effectiveness varied with the specific drug used (Joppa et al., 2005).

As expected, animals were significantly less active in response to IL-1β administration throughout the majority of the dark cycle in both Study 2 and Study 3. The current results show that pretreatment with the melanocortin antagonist blocked this reduction in activity. Decreased activity in response to IL-1β is consistent with reports in the literature (Morgan et al., 2004; Wieczorek and Dunn, 2006) and a consistent response to peripheral immune activation (e.g., LPS (Huang et al., 1999)). It has been reported that nonselective blockade of melanocortin receptors with the drug SHU9119 did not ameliorate LPS-induced hypoactivity and had no effect on its own (Huang et al., 1999). However, this study used different drugs (SH9119 and LPS) than the current study and a different experimental design (the SHU9119 was given 30 after LPS administration (as opposed to 15 min pretreatment in the current studies) and the injections were given in the early lights on period (as opposed to at the onset of lights off)), which likely contribute to the differing results.

The effect of melanocortin blockade on the RER response is similar to the pattern observed with food intake. In response to IL-1β, there is an acute reduction in RER, regardless of pretreatment condition, indicating an increase in fatty acid oxidation to meet the increased energetic demand of infection. This response persists for the entire evaluation period in animals pretreated with saline. However, in those pretreated with the melanocortin receptor antagonist, there was a return to control levels at the later timepoints. These results indicate that activity on the melanocortin receptors may not be important for the initiation of the RER response, but rather the longer term maintenance of the response. While similar to the pattern observed with food intake, the RER is response is unlikely to be secondary only to alterations in food intake, as the recovery in RER precedes food intake recovery by ~ 3 hrs. To our knowledge, this is the first report to detail the effects of cytokines and melanocortin receptor blockade on RER.

The metabolic rate data were particularly compelling. Previous reports have shown that MC receptor agonists (α-MSH or MT-II) increase oxygen consumption (Cowley et al., 1999; Hoggard et al., 2004), while MC receptor antagonists decrease oxygen consumption (Markison et al., 2005; Small et al., 2003). Oxygen consumption did not differ in response to HS014 alone (i.e. HS014/Veh animals did not differ from Sal/Veh animals). However, for animals pretreated with saline and then administered IL-1β, there was a significant increase in oxygen consumption, indicating an increase in metabolic rate. This increase in metabolic rate is consistent with an increased metabolic demand required to deal effectively with infection (e.g., mount a febrile response). In line with this hypothesis, mice lacking the IL-1 receptor antagonist have increased oxygen consumption, consistent with increased IL-1β activity in these animals (Somm et al., 2005). However, when animals were pretreated with HS014, there was a reversal in the response to IL-1β, such that animals administered IL-1β had a decreased oxygen consumption. These data are the first to show that pretreatment with a melanocortin antagonist can alter an animal’s metabolic response to cytokine administration.

The experiments in Study 4 were designed to evaluate the effect of melanocortin blockade on IL-1β-induced neuronal activation. For animals pretreated with saline, IL-1β induced a significant increase in Fos-ir+ cells, in line with the findings from Study 1. However, ICV pretreatment with HS014 blocked the IL-1β-induced increase in Fos-ir+ cells in the PVH. Further, HS014 treatment alone did not result in the induction of Fos-ir+ cells above baseline. This suggests that melanocortin receptor bearing neurons within the PVH likely play a role in mediating some or all of the IL-1β-induced metabolic responses, specifically late phase anorexia and decreased RER, dark phase hypoactivity, and increased oxygen consumption. Future studies directed at site-specific administration of the antagonist, or use of receptor selective antagonists will more directly address the involvement of MC4R in mediating each specific metabolic change. The relationship between MC3R and MC4R is complex; MC3R is an inhibitory autoreceptor on POMC neurons which produce a neuropeptide that acts as an agonist on the both the MC3R and MC4R. Because the current studies used an antagonist that is active on both receptors (albeit with greater potency for MC4R), it is currently impossible to tease out the precise role of each receptor subtype.

These data significantly extend our current knowledge of the role of melanocortin signaling in the CNS in the metabolic responses to inflammatory challenges. Few published experiments have included the simultaneous measurement of multiple metabolic parameters (food intake, activity, oxygen consumption and RER) and none have compared systemic IL-1β and TNF-α. At doses that elicited comparable anorexia and CNS activational responses, TNF-α affected fewer metabolic parameters. Future studies employing a higher dose of TNF-α will be able to address whether melanocortin involvement extends to this cytokine as well. We have shown that melanocortin receptor blockade can attenuate the metabolic response to IL-1β, particularly in the later phases of the response. Additionally, we have implicated the PVH as a likely site of action for the melanocortin mediation of cytokine activity.

Acknowledgements

GrantsSupported by NIH DK064086 (Reyes).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Keith W. Whitaker, Scripps Florida, Department of Biochemistry, Jupiter, FL 33458

Teresa M. Reyes, Scripps Florida, Department of Biochemistry, Jupiter, FL 33458 University of Pennsylvania, Department of Pharmacology, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

References

- Bagnol D, Lu X-Y, Kaelin CB, Day HE, Ollmann M, Gantz I, Akil H, Barsh GS, Watson SJ. Anatomy of an endogenous antagonist: relationship between Agouti-related protein and proopiomelanocortin in brain. J Neurosci. 1999;19:RC26. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-j0004.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluthe RM, Laye S, Michaud B, Combe C, Dantzer R, Parnet P. Role of interleukin-1beta and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in lipopolysaccharide-induced sickness behaviour: a study with interleukin-1 type I receptor-deficient mice. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;12:4447–4456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boddaert MS, Gerritsen WR, Pinedo HM. On our way to targeted therapy for cachexia in cancer? Curr Opin Oncol. 2006;18:335–340. doi: 10.1097/01.cco.0000228738.85626.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodnar RJ, Pasternak GW, Mann PE, Paul D, Warren R, Donner DB. Mediation of anorexia by human recombinant tumor necrosis factor through a peripheral action in the rat. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6280–6284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brebner K, Hayley S, Zacharko R, Merali Z, Anisman H. Synergistic effects of interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha: central monoamine, corticosterone, and behavioral variations. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:566–580. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00166-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AS, Marsh DJ, Trumbauer ME, Frazier EG, Guan XM, Yu H, Rosenblum CI, Vongs A, Feng Y, Cao L, Metzger JM, Strack AM, Camacho RE, Mellin TN, Nunes CN, Min W, Fisher J, Gopal-Truter S, MacIntyre DE, Chen HY, Ploeg LHVd. Inactivation of the mouse melanocortin-3 receptor results in increased fat mass and reduced lean body mass. Nat Genet. 2000;26:97–102. doi: 10.1038/79254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley MA, Pronchuk N, Fan W, Dinulescu DM, Colmers WF, Cone RD. Integration of NPY, AGRP, and Melanocortin Signals in the Hypothalamic Paraventricular Nucleus: Evidence of a Cellular Basis for the Adipostat. Neuron. 1999;24:155–163. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80829-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBoer MD, Marks DL. Cachexia: lessons from melanocortin antagonism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewys WD, Begg C, Lavin PT, Band PR, Bennett JM, Bertino JR, Cohen MH, Douglass HO, Engstrom PF, Ezdinli EZ, Horton J, Johnson GJ, Moertel CG, Oken MM, Perlia C, Rosenbaum C, Silverstein MN, Skeel RT, Sponzo RW, Tormey DC. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Med. 1980;69:491–497. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(05)80001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson A, Kovacs KJ, Sawchenko PE. A functional anatomical analysis of central pathways subserving the effects of interleukin-1 on stress-related neuroendocrine neurons. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14:897–913. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-02-00897.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson A, Liu C, Hart RP, Sawchenko PE. Type I interleukin-1 receptor in the rat brain: distribution, regulation, and relationship to sites of IL-1-induced cellular activation. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1995;361:681–698. doi: 10.1002/cne.903610410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon KC, Voss AC, Hustead DC, Group CCS. Definition of cancer cachexia: effect of weight loss, reduced food intake, and systemic inflammation on functional status and prognosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1345–1350. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes S, Bui S, Robinson BR, Hochgeschwender U, Brennan MB. Integrated control of appetite and fat metabolism by the leptin-proopiomelanocortin pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:4233–4237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071054298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayley S, Staines W, Merali Z, Anisman H. Time-dependent sensitization of corticotropin-releasing hormone, arginine vasopressin and c-fos immunoreactivity within the mouse brain in response to tumor necrosis factor-[alpha] Neuroscience. 2001;106:137–148. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoggard N, Rayner DV, Johnston SL, Speakman JR. Peripherally administered [Nle4,D-Phe7]-{alpha}-melanocyte stimulating hormone increases resting metabolic rate, while peripheral agouti-related protein has no effect, in wild type C57BL/6 and ob/ob mice. J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;33:693–703. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q-H, Hruby VJ, Tatro JB. Role of central melanocortins in endotoxin-induced anorexia. American Journal of Physiology. 1999;276:R864–R871. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.3.R864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huszar D, Lynch CA, Fairchild-Huntress V, Dunmore JH, Fang Q, Berkemeier LR, Gu W, Kesterson RA, Boston BA, Cone RD, Smith FJ, Campfield LA, Burn P, Lee F. Targeted Disruption of the Melanocortin-4 Receptor Results in Obesity in Mice. Cell. 1997;88:131–141. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joppa MA, Ling N, Chen C, Gogas KR, Foster AC, Markison S. Central administration of peptide and small molecule MC4 receptor antagonists induce hyperphagia in mice and attenuate cytokine-induced anorexia. Peptides. 2005;26:2294–2301. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviano A, Meguid MM, Inui A, Muscaritoli M, Rossi-Fanelli F. Therapy Insight: cancer anorexia–cachexia syndrome—when all you can eat is yourself. Nature Clinical Practice Oncology. 2005;2:158–165. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence CB, Rothwell NJ. Anorexic but not pyrogenic actions of interleukin-1 are modulated by central melanocortin-3/4 receptors in the rat. J. Neuroendocrin. 2001;13:490–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2001.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon LR, Whi AA, Kluger MJ. Role of IL-6 and TNF in thermoregulation and survival during sepsis in mice. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R269–R277. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.1.R269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling PR, Schwartz JH, Bistrian BR. Mechanisms of host wasting induced by administration of cytokines in rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E333–E339. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.3.E333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig DS, Mountjoy KG, Tatro JB, Gillette JA, Frederich RC, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E. Melanin-concentrating hormone: a functional melanocortin antagonist in the hypothalamus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1998;274:E627–E633. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.4.E627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markison S, Foster AC, Chen C, Brookhart GB, Hesse A, Hoare SRJ, Fleck BA, Brown BT, Marks DL. The Regulation of Feeding and Metabolic Rate and the Prevention of Murine Cancer Cachexia with a Small-Molecule Melanocortin-4 Receptor Antagonist. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2766–2773. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks DL, Ling M, Cone RD. Role of the central melanocortin system in cachexia. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1432–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MM, Clayton CC, Heinricher MM. Simultaneous analysis of the time course for changes in core body temperature, activity, and nociception following systemic administration of interleukin-1[beta] in the rat. Brain Research. 2004;996:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountjoy KG, Mortrud MT, Low MJ, Simerly RB, Cone RD. Localization of the melanocortin-4 (MCR-4) in neuroendocrine and autonomic control circuits in the brain. Molecular Endocrinology. 1994;8:1298–1308. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.10.7854347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau S, Rivest S. Effects of circulating tumor necrosis factor on the neuronal activity and expression of the genes encoding the tumor necrosis factor receptors (p55 and p75) in the rat brain: a view from the blood-brain barrier. Neuroscience. 1999;93:1449–1464. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plata-Salaman CR. Cytokines and anorexia: A brief overview. Semin Oncol. 1998;25:64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes TM, Sawchenko PE. Involvement of the Arcuate Nucleus of the Hypothalamus in Interleukin-1-Induced Anorexia. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:5091–5099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05091.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roselli-Rehfuss L, Mountjoy KG, Robbins LS, Mortrud MT, Low MJ, Tatro JB, Entwistle ML, Simerly RB, Cone RD. Identification of a receptor for gamma melanotropin and other proopiomelanocortin peptides in the hypothalamus and limbic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:8856–8860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M, Kim MS, Morgan DGA, Small CJ, Edwards CMB, Sunter D, Abusnana S, Goldstone AP, Russell SH, Stanley SA, Smith DM, Yagaloff K, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. A C-Terminal Fragment of Agouti-Related Protein Increases Feeding and Antagonizes the Effect of Alpha-Melanocyte Stimulating Hormone in Vivo. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4428–4431. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawchenko PE. Toward a new neurobiology of energy balance, appetite, and obesity: the anatomists weigh in. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402:435–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small CJ, Liu YL, Stanley SA, Connoley IP, Kennedy A, Stock MJ, Bloom SR. Chronic CNS administration of Agouti-related protein (Agrp) reduces energy expenditure. Intl J Obesity. 2003;27:530–533. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somm E, Henrichot E, Pernin A, Juge-Aubry CE, Muzzin P, Dayer J-M, Nicklin MJH, Meier CA. Decreased Fat Mass in Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist-Deficient Mice: Impact on Adipogenesis, Food Intake, and Energy Expenditure. Diabetes. 2005;54:3503–3509. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.12.3503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiergiel AH, Dunn AJ. Feeding, exploratory, anxiety- and depression-related behaviors are not altered in interleukin-6-deficient male mice. Behav Brain Res. 2006;171:94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisdale MJ. Biology of cachexia. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1997;89:1763–1773. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.23.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolchard S, Hare AS, Nutt DJ, Clarke G. TNF[alpha] mimics the endocrine but not the thermoregulatory responses of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS): Correlation with FOS-expression in the brain. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:243–248. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltri S, Smith JW. Interleukin 1 Trials in Cancer Patients: A Review of the Toxicity, Antitumor and Hematopoietic Effects. Oncologist. 1996;1:190–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek M, Dunn AJ. Relationships among the behavioral, noradrenergic, and pituitary-adrenal responses to interleukin-1 and the effects of indomethacin. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2006;20:477–487. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisse BE, Frayo RS, Schwartz MW, Cummings DE. Reversal of cancer anorexia by blockade of central melanocortin receptors in rats. Endocrinol. 2001;142:3292–3301. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.8.8324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisse BE, Ogimoto K, Schwartz MW. Role of hypothalamic interleukin-1[beta] (IL-1[beta]) in regulation of energy homeostasis by melanocortins. Peptides. 2006;27:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]