Abstract

Normal aging is associated with a decrease in dopaminergic function and a reduced ability to form new motor memories with training. This study examined the link between both phenomena. We hypothesized that levodopa would (a) ameliorate aging-dependent deficits in motor memory formation, and (b) increase dopamine availability at the dopamine type 2-like (D2) receptor during training in task-relevant brain structures. The effects of training plus levodopa (100mg, plus 25 mg carbidopa) on motor memory formation and striatal dopamine availability were measured with [11C] raclopride (RAC) positron emission tomography (PET). We found that levodopa did not alter RAC-binding potential at rest but it enhanced training effects on motor memory formation as well as dopamine release in the dorsal caudate nucleus. Motor memory formation during training correlated with the increase of dopamine release in the caudate nucleus. These results demonstrate that levodopa may ameliorate dopamine deficiencies in the elderly by replenishing dopaminergic presynaptic stores, actively engaged in phasic dopamine release during motor training.

Keywords: aging, motor, memory formation, positron emission tomography, neuropharmacology, neurotransmitter, neurorehabilitation

1. Introduction

Normal aging is associated with decreased ability to form new memories [36, 37, 41, 44], most notably episodic encoding [3, 36, 41]. A similar deficit is expressed in the motor domain, impairing the ability to encode the kinematic features of a previously practiced motor task in the primary motor cortex as a function of training [26, 58].

Dopamine is a major neurotransmitter that strengthens the specificity and duration of formed memories [32, 37, 40, 74]. Dopaminergic function, including dopaminergic receptors, transporters, and overall dopaminergic metabolic activity, are reduced with normal aging [20, 22, 23, 37, 44, 45, 57, 68]. Previous work showed that administration of the dopamine precursor levodopa could enhance training effects on motor memory formation in healthy elderly subjects [26] and stroke patients [27], and appears to enhance motor rehabilitation [59], as do noradrenergic agents [48]. One relative advantage in using dopaminergic agents versus, for example, amphetamines is that they exhibit fewer side effects and may be safer [24, 69].

The findings of enhanced memory encoding in the elderly after administration of levodopa [26] raise the hypothesis of a mechanistic link between dopaminergic function and training-induced motor memory formation. We reasoned that if such a link exists, administration of levodopa – which increases the presynaptic availability of endogenous dopamine – prior to training would lead to parallel increments in dopaminergic neurotransmission in task-relevant brain structures [49, 60] and in motor memory formation [9, 15]. Molecular imaging using the competitive D2 receptor ligand raclopride (RAC-positron emission tomography, PET) allows direct assessment of the brain dopamine system [16]. Endogenous release of dopamine increases synaptic dopamine concentration, resulting in increased occupancy of D2 receptors, and consequently decreased availability of dopamine D2 receptors for binding the radiotracer raclopride [43].

In the present study, we evaluated the effects of training plus levodopa on motor memory formation and on dopamine availability in the striatum. We also assessed levodopa effects on resting RAC-PET in the absence of training.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

Eleven healthy elderly subjects gave written informed consent and participated in this double-blind, placebo-controlled and randomized cross-over study. Four of them (age range 53-75 years, mean ± SD: 61 ± 10, one woman) participated to determine effects of levodopa on resting RAC-PET (CONDITION resting dopamine release). Seven volunteers (age range 55-86 years, mean ± SD: 65 ± 10, three women) participated in the main study to identify training effects with and without levodopa on RAC-PET (CONDITION training dopamine release) and motor memory formation (CONDITION motor training). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and by the National Institutes of Health Radiation Safety Commission Committee.

Inclusion criteria

All subjects fulfilled the following inclusion criteria for testing of motor memory formation [15]: (1) Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) applied to the primary motor cortex elicited isolated thumb movements in the absence of movements of any other digits, wrist, or arm; (2) There was a consistent (reproducible) direction of TMS evoked thumb movements in the baseline condition; (3) No medication was administered prior to the study that would affect the central nervous system (e.g., anti-psychotics and anti-depressants, or drugs interfering with the absorption of levodopa from the gastrointestinal tract) [50]s; (4) Routine medical and neurological examinations were normal and, (5) Handedness test showed strong right-handedness (handedness score ≥ 70 [51]).

In each session, subjects fasted for at least 2 hours preceding levodopa or placebo intake to prevent interference with drug absorption [50]. RAC-PET scans started 60 minutes after the oral intake of levodopa or a placebo to achieve appropriate peak plasma concentrations [54]. Measurements of systolic and diastolic blood pressures and heart rates, and subjects' ratings of attention to the task and general level of fatigue using visual scales with good internal consistency, reliability and objectivity [14, 28, 29] were taken three times during each session. Motor training kinematics were monitored during the experiment in all sessions involving training.

Subjects also received a high-resolution structural 3D magnetic resonance image (MRI) [19] of the brain using a 3 Tesla signa system (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI) for co-registration with PET images [78], and to rule out lesions or brain abnormalities [33].

2.2 Study design

Effects of levodopa on training-dependent formation of a motor memory

Each subject was studied in two separate sessions to determine the effects of levodopa (100 mg levodopa plus 25 mg carbidopa, p.o.) and placebo (identical capsule, p.o.) (see Fig. 1a) on formation of a motor memory (CONDITION motor training). Order of sessions (levodopa, placebo) was counterbalanced between subjects. Motor memory formation was tested using the methods described in several published studies that included the following procedures [8, 9, 15].

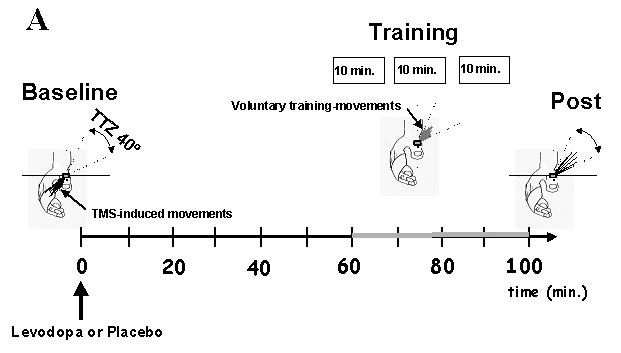

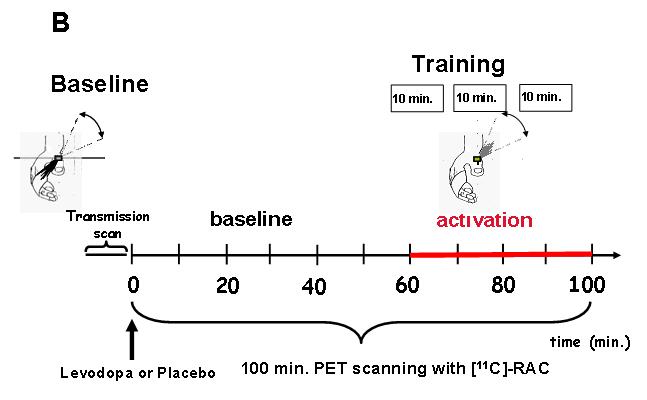

Fig. 1. Experimental setup.

A) Training-dependent formation of a motor memory: First, baseline TMS-evoked thumb movement direction was determined using an accelerometer positioned over the thumb. The training target zone (TTZ) was defined as a window of ± 20o centered in the direction opposite to Baseline. Subsequently, subjects took levodopa or placebo orally followed 60 min later by motor training consisting of brisk voluntary thumb movements performed at 1Hz in the direction of the TTZ, opposite to Baseline and divided in three 10 min blocks separated by approximately 3 min rest (see gray line between 60 and 100 min). At the end of training, we determined the change in the % of TMS-evoked thumb movements falling in the TTZ, the endpoint measure of the study. Note in the diagram the increase in the number of TMS-evoked movements falling in the TTZ at Post relative to Baseline.

B) Training-dependent dopamine release (PET): First, Baseline TMS-evoked thumb movement direction was determined using an accelerometer positioned over the thumb as described in Fig. 1a. Afterwards, subjects entered the scanner, and an 8-minute transmission scan was acquired. Then, subjects took levodopa or placebo orally simultaneously. Next, infusion of the tracer and scanning at “time zero” was started. For 60 minutes subjects rested with their eyes open in a dimly lit room, at the end of which they started motor training consisting of brisk voluntary thumb movements performed at 1Hz in the direction of the TTZ, opposite to Baseline and divided in three 10 min blocks (see gray line from 60 to 100 min). Training kinematics were carefully monitored inside the scanner for the entire time. The experimental time line for determination of resting-dopamine release was identical except that no training was performed between 60 and 100 min.

Baseline determination

Prior to training, 60 TMS stimuli were delivered to the scalp position that elicited optimal thumb movements at 0.1 Hertz (Hz), a rate that does not affect cortical excitability [13]. Subjects occasionally realized that the thumb had moved but could not determine its direction. In these trials, the baseline direction was defined as the direction of the mean angle of TMS-evoked movements (Fig. 1a, hand on the left, thin lines). Subjects' muscle relaxation was closely monitored by electromyography (EMG). Trials with background EMG activity were discarded from analysis (less than 5% of the data).

Motor training

After identifying the baseline TMS-evoked movement direction (Fig. 1a, hand on the left, training target zone = “TTZ”), subjects began the training period performing voluntary brisk thumb movements at a rate of 1 Hz in a direction opposite to the baseline direction (Fig. 1a, hand in the middle) in blocks of 10 min (minutes) for a total of 30 min. This kind of motor training leads to formation of a motor memory that encodes the kinematic details of the practiced motions in young individuals [15], a process that weakens substantially after age 50 [58]. Following each voluntary movement, the thumb returned to the start position by relaxation as monitored by EMG. The direction and magnitude of each voluntary movement were monitored on-line by EMG, and subjects were encouraged to perform the movements accurately and consistently. The experimenter and the subject were blind to the type of the intervention (levodopa versus placebo). To assess the consistency of training movements (motor training kinematics), we calculated the magnitude of the first peak acceleration of the training movements (s/m2), the angular difference between baseline directions of the TMS-evoked thumb movement and the training movement direction vectors (in degrees), and the dispersion of training movement direction vectors (measured as the length of the mean vector in a unit circle).

Post-training determination

TMS-evoked thumb movement directions were determined again with 12 TMS stimuli after the first and the second 10-minute block, and with 60 TMS stimuli after the third 10-minute block (= end of training) to estimate the time-course of directional changes in TMS-evoked movements [8, 26]. After completing the training period, TMS-evoked movement directions were measured again (TMS delivered at 0.1 Hz for 10 min for a total of 60 trials). Thus, there were four time samples (baseline and three training assessments).

Primary endpoint measure

To describe training effects on TMS-evoked movement directions, we defined the TTZ as a window of ± 20† centered on the training direction (Fig. 1a, hand on the left, “TTZ”). Our endpoint measure was the increase in the percentage of TMS-evoked movements that fell within the TTZ after training, a measure of the magnitude of formation of a motor memory [8, 9, 15] (Fig. 1a, hand on right, thin lines). By design, training was in the direction opposite to the TMS-evoked baseline direction. Therefore, the percentage of TMS-evoked movements within the TTZ prior to training was very small (< 5%).

Additionally, to determine corticomotoneuronal excitability, we measured motor threshold (MT), defined as the lowest stimulation intensity needed to elicit an MEP (motor evoked potential) of at least 50 μV with EMG (amplitude determined from peak-to-peak) in at least 5 of 10 trials in the target muscle [55] of the training agonist muscle [MT agonist], MT of the training antagonist muscle [MT antagonist], MEP amplitude of the training agonist [MEP agonist], and MEP amplitude of the training antagonist [MEP antagonist] at baseline and after training.

Effects of levodopa on training-dependent dopamine release

Subjects underwent two separate PET sessions, testing the effects of levodopa (100 mg levodopa / 25 mg carbidopa, p.o.) + training or placebo (identical capsule, p.o.) + training on dopamine release in the brain (CONDITION training dopamine release) (see Fig. 1b). Order of sessions (levodopa, placebo) was counterbalanced between subjects. Immediately prior to scanning, baseline TMS-evoked thumb movement and corticomotoneuronal excitability were assessed as described before (see Fig. 1b, left hand). Subsequent training movements in the scanner were performed in a direction opposite to baseline determinations (Fig. 1b, right hand). In preparation for the scanner, one venous catheter for radiotracer infusion was placed in position and a thermoplastic mask was used to prevent head motion. An 8-min transmission scan was obtained before tracer injection for attenuation correction. Following the transmission scan, the capsule with either levodopa or placebo was administered to the subjects. Then, up to 20 mCi of [11C]raclopride (range 15.62-20, mean + SD: 18.9 + 1.5) were infused (see Table 1) intravenously and dynamic emission PET scans were acquired. We used a bolus-plus-constant infusion (B/I) paradigm, with documented advantages over bolus infusions [71]. PET scans were performed with a General Electrics (GE) Advance tomograph, which acquires 35 simultaneous slices with 4.25 mm inter-slice distance. Scans were acquired in 3D mode with septa removed producing a reconstructed resolution of 6 mm in all directions. Scanning proceeded for 100 min. The MRI was always acquired within two weeks of the PET scanning in a separate session.

Table 1.

[C 11]-raclopride doses used in the PET studies.

| CONDITION | Dose [mCi], Levodopa Session |

Dose [mCi], Placebo Session |

|---|---|---|

| Training, Subject 1 | 16.66 | 19.71 |

| Training, Subject 2 Training, Subject 3 |

17.35 20.04 |

20.35 19.3 |

| Training, Subject 4 Training, Subject 5 |

17.5 19.79 |

18.5 19.71 |

| Training, Subject 6 | 15.62 | 19.85 |

| Training, Subject 7 | 20.44 | 19.99 |

| Rest, Subject 1 | 19.12 | 17.82 |

| Rest, Subject 2 | 19.56 | 19.64 |

| Rest, Subject 3 | 18.25 | 17.17 |

| Rest, Subject 4 | 18.99 | 17.48 |

Differences between [11C] raclopride doses (mCi) infused in the placebo versus levodopa sessions were not significant, for both CONDITIONS (CONDITION training dopamine release, resting dopamine release). Also, comparing the placebo sessions (CONDITION training dopamine release versus CONDTION resting dopamine release) and the levodopa sessions (CONDITION training dopamine release versus CONDTION resting dopamine release), no significant differences were found.

Effects of levodopa on resting dopamine release

Subjects underwent two separate PET sessions, testing the effects of levodopa (100 mg levodopa plus 25 mg carbidopa, p.o.) + rest and placebo (identical capsule, p.o.) + rest on endogenous dopamine release (CONDITION resting dopamine release). Subject preparation, PET, and MRI scans were performed as described above. Again, up to 20 mCurie (mCi) of [11C]raclopride (range 17.17-19.64, mean + SD: 18.5 + 1.0) were administered (see Table 1) intravenously. Order of sessions (levodopa, placebo) was counterbalanced between subjects.

2.3 PET Data analysis

Image registration

Wavelet denoising of PET frames and motion correction during the scan interval were performed using the methods reported in previous studies [49, 78]. Decay-corrected PET frames were averaged from 40-50 min after the start of the raclopride infusion for “baseline” (rest in both the CONDITION resting dopamine release and CONDITION training dopamine release), and over 40 min starting 5 min after training onset (min 60-100) for the “task” (rest in the CONDITION training dopamine release and training in the CONDITION resting dopamine release). Note that when “effects of levodopa on resting dopamine release” (CONDITION resting dopamine release) were assessed, subjects were asked to rest during the “task”, that is, during min 60-100. Data analysis led to comparable signal-to-noise ratios before and after training following previously described techniques [46, 71]). [11C] raclopride-derived images were resampled using the same transformation matrix. Under equilibrium conditions, binding potential (BP) can be obtained directly from the radioactivity concentration (C) of the receptor-rich or target region (C[nCi/ml]) (regions of interest, “ROI”, see below) and a receptor-poor or background region (C'[nCi/ml]) (the cerebellum, “CER”, see below) as the ratio BP = (C – C')/C' [10, 71]. BP equals the equilibrium ratioof bound ligand to free plus non-specifically bound tracer under the assumptions that non-specific binding is uniform throughout the brain. Therefore, the percentage change in BP (delta BP) caused by a stimulus (e. g., training plus levodopa) is defined as:

where “baseline” refers to the rest period and “training” refers to the training period [71]. Since the cerebellum (CER) is devoid of D2 and D3 receptors, a region of 15 mm in diameter over the CER was used as the PET baseline reference. This region over the CER was drawn on the MRI scan and applied to the coregistered and averaged [11C]-RAC PET images.

Regions of interest

Image analysis was performed within MEDx (version 4.43; Sensor Systems, Sterling, VA, USA). ROIs were chosen in task-relevant brain structures in the striatum (left and right dorsal caudate (DCA) and dorsal putamen (DPU)), a region with a high concentration of D2 receptors. These ROIs were traced on MRI slices oriented in the coronal plane to measure RAC-BP [49] (see Fig. 2). In short, the boundary between the ventral striatum (inferiorly; VS), DCA, and DPU (superiorly) was defined by a line joining (a) the intersection between the outer edge of the putamen with a vertical line going through the most superior and lateral point of the internal capsule (point a, Fig. 2); and (b) the center of the portion of the anterior commissure (AC) transaxial plane overlying the striatum (point b, Fig. 2). This line was extended to the internal edge of the caudate (point c, Fig. 2). The DCA was sampled from its anterior boundary to the AC coronal plane. Thus, for the DCA, the sampled region included the dorsal part of the head of the caudate and the anterior to posterior boundaries. In slices posterior to the AC plane, the medial boundary of the DPU was the globus pallidus. As stated above, the CER, a structure devoid of D2 and D3 receptors in humans, was used as the region of reference. All ROIs on the PET images were identified using subjects' own T1 weighted structural MRI images. Based on data from animal studies, it has been estimated that a 1% decrease in striatal [11C]raclopride BP reflects at least an 8% increase in extracellular endogenous dopamine levels [4].

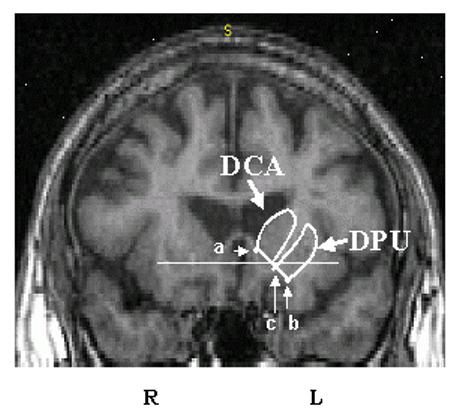

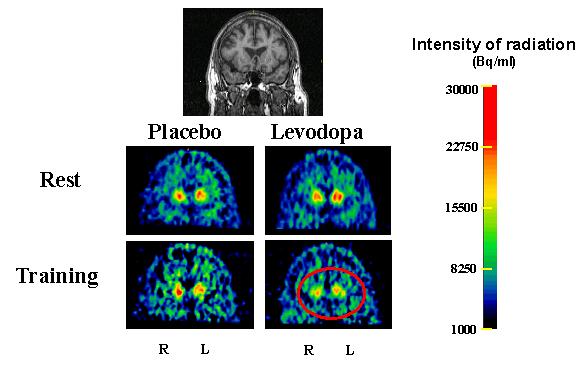

Fig. 2. Regions of interest in the striatum.

MRI coronal slice 7 mm anterior to the anterior commmissure (AC) showing the dorsal caudate (DCA) and dorsal putamen (DPU) regions of interest. The horizontal solid line identifies the transaxial anterior commissure-posterior commissure plane. The inferior boundary of the DCA and DPU was defined by a line joining the intersection between the outer edge of the putamen with a vertical line going through the most superior and lateral point of the internal capsule (point a); and (b) the center of the portion of the anterior commissure transaxial plane overlying the striatum. This line was extended to the internal edge of the caudate (point c). The DCA was sampled from its anterior boundary to the AC coronal plane. The DPU was sampled from its anterior to posterior boundaries (adapted from Mawlawi et al., 2001).

2.4 Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed by an investigator blind to the intervention type. No significant deviation from normal distribution could be assessed using the Kolmogorow-Smirnov test of normality (set at p < 0.05) prior to data analysis.

Blood pressure, heart rate, attention, fatigue

Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA RM) with a polynomial contrast analysis on the factor TIME was used to test the influence of the repeated factors TIME base, 15 min, post, DRUG levodopa, placebo and the between subjects factor CONDITION training dopamine release, memory formation on systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, attention to the task and fatigue over the course of the study.

A separate ANOVA RM with the same factors TIME base, 15 min, post and DRUG levodopa, placebo was implemented to test effects in the CONDITION resting dopamine release. Additional unpaired t-tests compared these parameters at each time point (base, 15 min, post) between the CONDITION training dopamine release and the CONDITION resting dopamine release.

Motor training kinematics

Motor training kinematics (magnitude of first-peak acceleration of training movements, angular difference between the training movement direction and the baseline direction vectors, dispersion of training movement directions) and movement threshold (MovT) were analyzed using ANOVARM with the repeated factor DRUG levodopa, placebo and the between subjects factor CONDITION training dopamine release, memory formation.

Corticomotoneuronal excitability at baseline

Measures of corticomotoneuronal excitability at baseline including MT agonist, MT antagonist, MEP agonist, and MEP antagonist were analyzed using ANOVARM for the repeated factor DRUG levodopa, placebo and the between subjects factor CONDITION training dopamine release, memory formation.

Training effects

Training effects on corticomotoneuronal excitability was measured using ANOVARM with a polynomial contrast analysis on the factor TIME base, 10 min, 20 min, post and the repeated factor DRUG levodopa, placebo.

Training effects on the % of TMS-evoked movements in the TTZ (primary outcome measure of motor memory formation) were tested using ANOVARM with a polynominal contrast on the factor TIME base, 10 min, 20 min, post and the repeated factor DRUG levodopa, placebo in the CONDITION memory formation.

[11C] raclopride doses (mCi) infused in the CONDITIONtraining dopamine release were compared between the placebo and the levodopa sessions using paired t-tests; likewise, doses infused in the CONDITIONresting dopamine release were compared between the placebo and the levodopa sessions using paired t-tests. Then, [11C] raclopride doses (mCi) infused in the placebo session of CONDITION training dopamine release were compared with the doses infused in the placebo session of CONDITION resting dopamine release using unpaired t tests; likewise, doses infused in the levodopa session of CONDITION training dopamine release were compared with the doses infused in the levodopa session of CONDITION resting dopamine release using unpaired t tests.

Training-dependent change of RAC-BP (delta RAC-BP) was tested using ANOVARM with the factor SITE dorsal caudate, dorsal putamen, SIDE left hemisphere, right hemisphere, and DRUG levodopa, placebo. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to correlate ‘delta RAC-BP in left DCA (= DCA opposite the moving hand), levodopa minus placebo’ with the ‘% of TMS-evoked movements in the TTZ, levodopa minus placebo’. For exploratory purposes, Pearson's correlation coefficient was also calculated for ‘delta RAC-BP in right DCA, levodopa minus placebo’ with ‘% of TMS-evoked movements in the TTZ, levodopa minus placebo’.

Data were considered significant at a level of p < .05. If significant effects were found in the ANOVA RM; post hoc testing using paired t-tests were conducted to obtain descriptive information on the precise timings of the effect. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM, unless stated otherwise.

3. Results

3.1 Blood pressure, heart rate, attention, fatigue

Attention, fatigue, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate changes were comparable across CONDITION training dopamine release, memory formation, DRUG levodopa, placebo, and TIME base, 15 min, post (see Table 2). In both CONDITION training dopamine release and CONDITION memory formation, systolic blood pressure decreased over time to a similar extent with levodopa and placebo (main effects of TIME; linear trends, F(1,6) = 27.9, p = 0.002 and F(1,6) = 14.2, p = 0.022, respectively).

Table 2.

Measurements of blood pressure, heart rate, attention, and fatigue (mean ± SE)

| Measurement | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROUP, DRUG | ||||

| Training- dependent motor memory formation Levodopa |

fatigue | 5.5 + 0.3 | 4.9 + 0.5 | 5.7 + 0.4 |

| attention | 5.9 ± 0.3 | 5.9 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | |

| HR | 71 ± 2 | 67 ± 3 | 65 ± 3 | |

| BP | 123/74 ± 4/4 | 114/70 ± 3/3 | 107/69 ± 3/3 | |

| Training- dependent motor memory formation Placebo |

fatigue | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 0.4 |

| attention | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | |

| HR | 72 ± 3 | 69 ± 2 | 71 ± 3 | |

| BP | 124/74 ± 4/4 | 116/73 ± 5/3 | 111/73 ± 3/2 | |

| Resting dopamine release (PET) Levodopa |

fatigue | 5.9 ± 0.4 | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 5 ± 0.4 |

| attention | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.4 | |

| HR | 69 ± 4 | 67 ± 4 | 61 ± 4 | |

| BP | 115/73 ± 6/2 | 108/64 ± 4/3 | 100/64 ± 4/3 | |

| Resting dopamine release (PET) Placebo |

fatigue | 5.9+ 0.4 | 6 + 0.4 | 6 + 0.4 |

| attention | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 5.5 ± 0.3 | 5 ± 0.4 | |

| HR | 74 ± 4 | 67 ± 5 | 70 ± 5 | |

| BP | 118/73 ± 4/4 | 110/70 ± 5/4 | 108/69 ± 7/4 | |

| Training- dependent dopamine release (PET) Levodopa |

fatigue | 5.6 ± 0.3 | 5.6 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.4 |

| attention | 5.7 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | |

| HR | 71 ± 2 | 66 ± 3 | 63 ± 3 | |

| BP | 123/74 ± 6/4 | 111/68 ± 4/2 | 104/66 ± 2/2 | |

| Training- dependent dopamine release (PET) Placebo |

fatigue | 5.3 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.4 | 4.9 ± 0.4 |

| attention | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 6.1 ± 0.4 | 5.9 ± 0.5 | |

| HR BP |

72 ± 4 124/74 ± 5/5 |

67 ± 3 113/71 ± 5/4 |

69 ± 3 109/71 ± 4/3 |

|

Attention to the task and general fatigue were self-assessed by the subjects using visual analog scales (1, lowest and 7, highest). Heart rate (HR): beats/minute. Blood pressure (BP): mmHg (systolic/diastolic). Three measurements were taken in each session: “1” before, “2” after 15 minutes of training, and “3” after training. SE: standard error of the mean

Note that systolic BP decreased progressively over time in both groups with both levodopa and placebo in the absence of significant changes in other parameters.

Unpaired t-tests between CONDITION training dopamine release and CONDITION resting dopamine release for systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate, attention, and fatigue were also comparable (see Table 2).

3.2 Motor training kinematics

No significant differences were observed in motor training kinematics across DRUG and CONDITION both in the magnitude of first-peak acceleration and in the dispersion of training movement directions (see Table 3), indicating that subjects' training with regard to briskness of movement and consistency of training direction was comparable in the TMS laboratory and in the PET scanner (no difference in CONDITION), and that differences in training kinematics may not account for the difference in memory formation observed between levodopa and placebo (no difference in DRUG).

Table 3. Motor training kinematics (mean ± SE).

Magnitude of first peak acceleration of training movements (m/s2), angular difference between the training movement direction and the baseline direction vectors (degrees), and dispersion of training movement directions (length of unit vector) showed no significant interactions or main effects for DRUG levodopa, placebo or CONDITION motor training, training dopamine release.

| CONDITION, DRUG |

Peak Acceleration [m/s2] |

Angular Dispersion [length of unit vector] |

Angular Difference [degrees] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training-dependent motor memory formation Levodopa |

4.8 ± 0.3 | 0.94 ± 0.06 | 184 ± 19 |

| Training-dependent motor memory formation Placebo |

4.5 ± 0.5 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 190 ± 19 |

| Training-dependent dopamine release (PET) Levodopa |

4.9 ± 0.5 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 194 ± 18 |

| Training-dependent dopamine release (PET) Placebo |

5.0 ± 0.4 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 208± 21 |

3.3 Motor cortex excitability

At baseline, MT (Table 4a) and MEP amplitudes (MEP agonist base and MEP antagonist base; Table 4b) were comparable across DRUG and CONDITION, showing that subjects' showed comparable motor cortex excitability in the different study days. Motor training resulted in a trend (n. s.) for larger MEP amplitudes in MEP agonist post after both levodopa and placebo, see Table 4b. Thus, the differential results in motor memory formation may not be due to differences in baseline or training-induced motor cortex excitability.

Table 4. Motor cortex excitability (mean ± SE).

A. Motor threshold (MT) before (MT base) and after (MT post) training in muscles mediating movements in the training (MTagonist) and baseline (MT base) direction expressed as percentage of maximal stimulator output.

| CONDITION, DRUG |

MT agonist base [%] |

MT agonist post [%] |

MT antagonist base [%] |

MT antagonist post [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training-dependent motor memory formation Levodopa |

56.3 ± 3.2 | 55 ± 3.4 | 55.4 ± 3.2 | 55.4 ± 3.2 |

| Training-dependent motor memory formation Placebo |

56.6 ± 2.8 | 55.8 ± 2.5 | 55.7 ± 2.7 | 55.7 ± 2.7 |

| Training-dependent dopamine release (PET) Levodopa |

58.6 ± 4.0 | 59.4 ± 3.9 | ||

| Training-dependent dopamine release (PET) Placebo |

59.1 ± 3.9 | 59.6 ± 3.8 | ||

| B. Motor evoked potentials (MEP) before (MEP base) and after (MEP post) training in muscles mediating movements in the training (MEPagonist) and baseline direction (MEP antagonist) expressed in mV. Note that training elicited a trend for amplitude increase in MEP agonist for both levodopa and placebo, in the absence of changes in MEP antagonist. | ||||

| DRUG | MEP agonist base [mV] |

MEP agonist post [mV] |

||

| Training-dependent motor memory formation Levodopa |

1.18 + 0.4 | 1.41 + 0.5 | ||

| Training-dependent motor memory formation Placebo |

1.017 + 0.2 | 1.412 + 0.3 | ||

| DRUG | MEP antagonist base [mV] |

MEP antagonist post [mV] |

||

| Training-dependent motor memory formation Levodopa |

1.16 + 0.3 | 1.07 + 0.2 | ||

| Training-dependent motor memory formation Placebo |

1.98 + 0.2 | 0.92 + 0.1 | ||

3.4 Encoding a motor memory

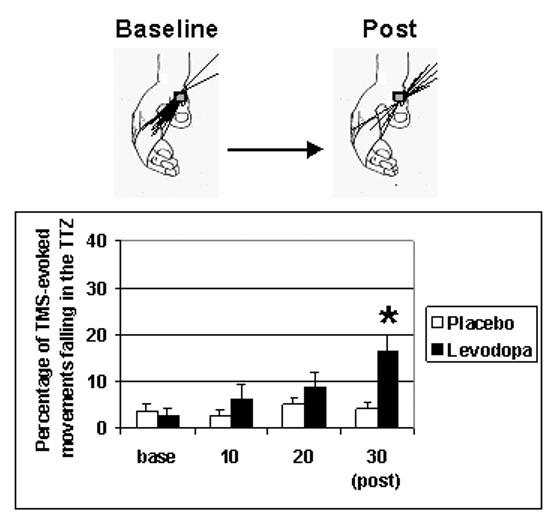

ANOVARM showed a significant interaction between DRUG levodopa, placebo and TIME base, 10 min, 20 min, post (F(1,6) = 3.7, p = 0.032) (see Fig. 3). Post-hoc testing revealed that training under placebo did not change TMS-evoked thumb movements falling in the TTZ, which is consistent with a previous report on the effect of age on the response to training [58]. On the other hand, levodopa+training led to a significant increase in the percentage of TMS-evoked thumb movements in TTZ relative to resting baseline at 30 minutes (from 2.4+ 1.8% to 16.3 + 3.8 %; t(6) = −3.4, p=0.014; Fig. 3, 30 min [post], black bar).

Fig. 3. Training-dependent formation of a motor memory.

Percentage of TMS-evoked thumb movements falling in the TTZ. Administration of Levodopa substantially enhanced the effects of motor training on the % of TMS-evoked movements falling in the TTZ relative to placebo, which became significant after 30 min training (30 min [post], black bar; asterix denoting significance, p < 0.05). Inset above the bar graph shows an example of the increase in TMS-evoked movements (predominantly in flexion-adduction at Baseline) towards the TTZ in extension-abduction (the training direction) after 30 minutes training. Note that 60 TMS-evoked movements were acquired at baseline ([base]) and after 30 minutes of training (30 min [post]). After 10 and after 20 minutes of training, 12 TMS-evoked movements were acquired.

3.5 Dopamine release

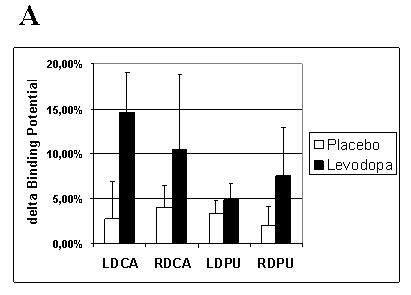

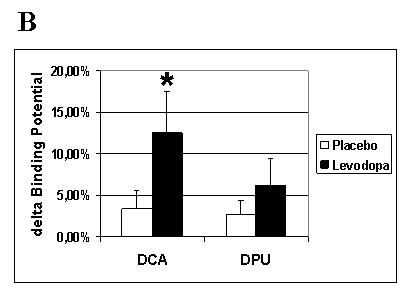

There was no significant difference between [11C] raclopride doses (mCi) infused between the placebo and levodopa sessions for either CONDITION, nor in the CONDITION training dopamine release compared to the CONDITION resting dopamine release (see Table 1). At rest, there were no significant changes in dopamine release over time after either levodopa or placebo (n. s.). With training, a significant SITE × DRUG interaction (F (1,6),= 9.2, p= 0.023) was observed, with no interaction of main effect for the factor SIDE. Post hoc analyses, after pooling over the factor SIDE revealed a significantly higher delta RAC-BP with levodopa than with placebo for the DCA, and a trend for the DPU (t(6) = −3.1, p = 0.022 and t(6) = −2.4 p = 0.054, respectively), consistent with increased dopamine release (see Fig. 4 for single subject, and 5a,b and Table 5 for group data). The magnitude of drug-induced difference (levodopa minus placebo) in RAC-BP in left DCA during training significantly correlated with the difference in % change in TMS-evoked movements in the TTZ (levodopa minus placebo) (R =0.77, R2 = 0.59; p = 0.044) (see Fig. 5c). The right DCA did not show a similar correlation.

Fig. 4. Training-dependent dopamine release in PET.

MRI image (top row) and PET images for the dopamine D2 radiotracer 11-C-Raclopride at the level of the striatum (bottom rows) in a 62 yo subject. Dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in both the left and the right dorsal caudate declined during training in the levodopa (see red circle) but not the placebo session, indicating release of endogenous dopamine. Note also that there was no change in RAC-BP at rest after levodopa, compared to the placebo condition. R = right hemisphere, L = left hemisphere, Bq = Bequerel, ml = milliliter

Fig. 5. Training-dependent dopamine release as assessed during RAC-PET.

Training under the effects of levodopa elicited more prominent changes in RAC-BP (endogenous dopamine release) than under placebo for all four regions of interest. ANOVA SITE × SIDE × DRUG revealed a significant interaction of SITE × DRUG (A). Post-hoc testing pooling data over SIDE (B) revealed a significant difference for the dorsal caudate in the levodopa compared to the placebo condition (*, p < 0.05). Note in C the significant correlation (r =0.77, p = 0.044) between training-dependent motor memory formation (% change in TMS-evoked movements falling in the TTZ levodopa minus placebo) and dopamine release in the left dorsal caudate (% change in RAC-BP in LDCA, levodopa minus placebo).TTZ = training target zone; D = dopamine; P = placebo; RAC-BP = raclopride binding potential; LDCA = left dorsal caudate; RDCA = right dorsal caudate; LDPU = left dorsal putamen; RDPU = right dorsal putamen; SITE = hemispheric site (dorsal caudate or dorsal putamen), SIDE = hemispheric side (left or right)

Table 5. [C 11] raclopride binding potential at rest and during the task, and average change (%).

A. [C 11] raclopride binding potential (mean ± SE) and average change (delta binding potential, in %) expressed in means and standard deviations for levodopa, CONDITION training dopamine release

| Dorsal caudate, levodopa |

Dorsal caudate, levodopa |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | |||||

| Rest | Task | Delta (%) | Rest | Task | Delta (%) | |

| BP (±SE) |

1.58 0.50 |

1.36 0.40 |

13.87 | 1.65 0.30 |

1.47 0.28 |

10.88 |

| Dorsal putamen, levodopa |

Dorsal putamen, levodopa |

|||||

| Left | Right | |||||

| Rest | Task | Delta (%) | Rest | Task | Delta (%) | |

| BP (±SE) |

2.39 0.31 |

2.27 0.25 |

4.95 | 2.35 0.22 |

2.18 0.17 |

7.21 |

|

B. [C 11] raclopride binding potential (mean ± SE) and average change (delta binding potential, in %) expressed in means and standard deviations for placebo, CONDITION training dopamine release | ||||||

| Dorsal caudate, placebo |

Dorsal caudate, placebo |

|||||

| Left | Right | |||||

| Rest | Task | Delta (%) | Rest | Task | Delta (%) | |

| BP (±SE) |

1.52 0.41 |

1.49 0.36 |

2.42 | 1.70 0.30 |

1.64 0.30 |

3.67 |

| Dorsal putamen, placebo |

Dorsal putamen, placebo |

|||||

| Left | Right | |||||

| Rest | Task | Delta (%) | Rest | Task | Delta (%) | |

| BP (±SE) |

2.45 0.21 |

2.38 0.2 |

3.08 | 2.4 0.24 |

2.34 0.16 |

2.0 |

|

C. [C 11] raclopride binding potential (mean ± SE) and average change (delta binding potential, in %) expressed in means and standard deviations for levodopa, CONDITION resting dopamine release | ||||||

| Dorsal caudate, levodopa |

Dorsal caudate, levodopa |

|||||

| Left | Right | |||||

| Rest | Task | Delta (%) |

Rest | Task | Delta (%) | |

| BP (±SE) |

1.91 0.24 |

1.98 0.41 |

3.56 | 1.95 0.1 |

2.0 0.24 |

0.27 |

| Dorsal putamen, levodopa |

Dorsal putamen, levodopa |

|||||

| Left | Right | |||||

| Rest | Task | Delta (%) |

Rest | Task | Delta (%) | |

| BP (± SE) |

2.41 0.17 |

2.51 0.25 |

4.05 | 2.35 0.02 |

2.49 0.02 |

6.0 |

|

D. [C 11] raclopride binding potential (mean ± SE) and average change (delta binding potential, in %) expressed in means and standard deviations for placebo, CONDITION resting dopamine release | ||||||

| Dorsal caudate, placebo |

Dorsal caudate, placebo |

|||||

| Left | Right | |||||

| Rest | Task | Delta (%) |

Rest | Task | Delta (%) | |

| BP (±SE) |

2.12 0.27 |

2.01 0.29 |

5.1 | 2.14 0.31 |

2.04 0.31 |

4.8 |

| Dorsal putamen, placebo |

Dorsal putamen, placebo |

|||||

| Left | Right | |||||

| Rest | Task | Delta (%) |

Rest | Task | Delta (%) | |

| BP (±SE) |

2.69 0.17 |

2.56 0.18 |

4.61 | 2.58 0.26 |

2.50 0.30 |

2.86 |

BP = binding potential; SE = standard error of the mean; DCA = dorsal caudate; DPU = dorsal putamen; delta = % changes in BP.

Rest = baseline condition; Task = Motor training in the CONDITION training dopamine release; Task = Rest in the CONDITION resting dopamine release

4. Discussion

The main findings of this study were that levodopa enhanced both training effects on motor memory formation and dopamine release in the dorsal caudate nucleus in healthy elderly subjects. The increase in dopamine release in the left caudate correlated with the magnitude of motor memory formation, indicative of a functional link between the two phenomena.

4.1 Mechanisms of dopamine-enhanced motor memory formation

Dopaminergic systems are capable of delivering precisely timed information to specific target structures [61] and modulate plasticity of glutamatergic circuits [64, 73]. This ability to modulate plasticity of non-dopaminergic circuits (“metaplasticity” [76]) is present when the dopaminergic activity is synchronous with the glutamatergic input. This selectivity in upregulating active synapses, while downregulating inactive synapses in a task-specific manner [12, 73] increases the signal-to-noise ratio for a specific task.

In the elderly, this endogenous mechanism may be compromised, because dopaminergic stores are sensitive to injuries, like oxidative stress, that accumulate over the lifetime [37, 45]: Neuropathological as well as receptor imaging studies [39, 77] have revealed a 7-11% reduction per decade in D2 receptors starting at the age of about 20 years. With advancing age, D1 receptor loss has been reported in the striatum [31] and in the frontal cortex [17] and loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra in both humans [23] and monkeys [22]. In the present study of healthy elderly subjects, overall BP values (i.e., both at rest and during the task) were lower than BP values reported for younger healthy subjects [49], pointing to a decrease in D2 receptor availability with advancing age [68].

Previous findings suggested that training enhances intracortical local networks in the primary motor cortex underlying representation of movements in the training direction, and weakens representation of movements in the non-trained direction [15]. These changes outlast the training period resulting in formation of a motor memory that encodes the kinematic details of the practiced movements [9, 15]. The basal ganglia have a major role in organizing information, strengthening relevant behavioral input while inhibiting “noise” in the system [11, 34, 73]. The primary motor cortex receives extensive dopaminergic input from midbrain structures directly and via the striatum, as demonstrated in tracer studies in macaque monkeys [75] and in human imaging studies using the RAC-PET [62-64]. Corticol-basal ganglia circuits [1] have shown to be crucially involved in encoding of motor memories [34], probably guided by the reward-sensitive function of the dopamine-containing neurons in the substantia nigra [21]. Owing to the reciprocal connections between the basal ganglia, cortex, and brain stem structures, it is difficult to define the specific roles of the striatum and the cortex in information processing [16].

The current study examined potential mechanisms underlying the enhancement of training effects and the role of levodopa on motor memory formation in elderly adults, both in motor cortical networks using TMS, and in the striatum using PET. Our finding of a parallel increase in dopamine release in the striatum and motor memory formation, after exogenously “replenishing“ dopaminergic stores, suggests a facilitatory role of dopamine on cortical [3, 30, 52] and striatal [73] synapses engaged during the training task. In other words, we hypothesize that enhanced dopaminergic neurotransmission might have strengthened the representation of the practised movement direction and weakened the representation of the non-training direction, resulting in an increase in the number of movements falling in the training-target zone. This interpretation is further supported by the positive correlation of dopamine release and encoding success. The observed dopamine-enhanced memory formation may then be due to the facilitatory role of dopamine in the induction of cortical [3, 30, 52] and striatal [73] long-term potentiation (LTP) in active synapses.

The levodopa doses administered to our healthy subjects were relatively low compared to dosages used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease [7]. The fraction of dopamine that is stored and thus may be subsequently released during training may increase with larger doses of levodopa [18], and previous studies have suggested a dose-response effect in regard to learning enhancement [42]. However, since possible side-effects like nausea, vomiting, and dizziness are dose-dependent [7] and our subjects were first-time users of levodopa, we chose to employ the lowest dose that has shown to be effective in improving learning and memory formation in previous studies [26, 27, 42]. In future studies that use levodopa over an extended period of time (e. g., over the course of a rehabilitative treatment), it might be of interest to study if a gradual increase in dose further improves training outcome.

4.2 Influence of motor performance and arousal on dopamine release

The difference in the levodopa and placebo sessions cannot be explained by motor performance or unspecific arousal differences. Subjects' attention to the training task, fatigue levels, blood pressure and heart rate (Table 2) as well as motor training kinematics (Table 3) were comparable across drug sessions, a finding consistent with previous reports of levodopa-effects [26, 42]. Similarly, measures of corticomotoneuronal excitability, such as motor thresholds and amplitude of motor evoked responses did not differ at baseline or after training across treatment sessions (Table 4), in accordance with previous studies [26, 79].

Furthermore, we observed a significant differential effect between levodopa and placebo sessions in the dorsal caudate (“associate striatum”) but not in the dorsal putamen (“motor striatum”) [1]; the differential effect in the left dorsal caudate correlated with the magnitude of improved motor memory formation. Together, these findings indicate that premedication with levodopa did not induce a difference in motor performance but rather an increase in memory formation with training.

4.3 Phasic versus tonic dopaminergic enhancement

The results of this study provide evidence for the hypothesis that dopaminergic agents enhance training effects on motor memory formation in elderly adults. A likely mechanism for this effect would be replenishing dopaminergic presynaptic stores, known to decrease with aging [23, 37]. Levodopa, rather than dopamine agonists, may be most promising in non-PD subjects, since phasic dopamine release during training may be required instead of the tonic dopaminergic stimulation by dopamine agonists. This interpretation is in line with data showing that phasic dopamine release is crucial for learning success [25], while dopamine agonists -- that lead to a tonic stimulation of dopamine receptors -- decrease learning success [5].

Previous studies on primates [2] and the less affected striatum of patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) [66, 67] had indicated that levodopa administration does not significantly alter striatal [11C] RAC-BP at rest. Our study confirmed these results, showing that RAC-BP at rest did not differ after levodopa administration compared to placebo. Together, these data suggest that in the intact striatum, sufficient catabolism as well as storage capacity for dopamine prevents newly synthesized dopamine from being released in the resting state. This may not apply to the severely dopamine depleted striatum found in the clinically affected side of PD patients. Here, levodopa would probably increase synaptic dopamine availability at rest [66, 67].

4.4 Outlook: Clinical implications

Elderly subjects [36, 38] represent the main population at risk for stroke. About two-thirds of stroke survivors have residual neurological deficits [35]. Motor disability reduces functional independence by compromising activities of daily living, such as dressing, bathing, and writing [72], but motor disability resulting from this condition is not routinely treated with dopaminergic agents except for small clinical trials [27, 59]. Our findings provide a possible mechanistic explanation for the beneficia l effects of these interventions on recovery of motor function after stroke, most likely through modulation of synaptic plasticity (metaplasticity, [76]) in crucial motor networks [47, 56, 65, 70]. These changes could result in performance improvements in learning of motor sequences [6] and activities of daily living [59]. The present study provides the foundation for future clinical trials probing the effects of dopaminergic agents in the neurorehabilitative setting. Furthermore, age-related deficits in encoding new memories, affecting at least half the population over 65 years [53], may possibly be ameliorated by dopaminergic agents, an issue for future investigation.

4.5 Conclusion

Our findings provide insight into the mechanisms of levodopa-induced enhancement of training effects in motor memory formation: After premedication with levodopa, elderly individuals are able to release more dopamine during training for motor memories in relevant brain structures (that is, in the dorsal caudate contralateral to the moving hand), and this increased neurotransmitter release is positively correlated with improvements in motor memory formation. These findings raise the hypothesis that levodopa may ameliorate dopamine deficiencies in the elderly by replenishing dopaminergic presynaptic stores, actively engaged in phasic dopamine release during motor training. The results of the study are important with regard to the understanding of neurobiological mechanism(s) underlying motor memory formation and with regard to the development of clinical applications in neurorehabilitation [27, 59, 69].

5. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to A. F. (Fl 379-4/1), the Bundesministerium für Forschung und Bildung to A.F (01GW0520, part 4), the Interdisciplinary Center of Clinical Research Münster to S. K. (IZKF Projects FG2 and Kne3/074/04), the Innovative Medizinische Forschung Münster to A. F. (FL110605) and (KN520301) and the Volkswagen Stiftung to S. K. (Az.: I/80 708).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

6. Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Alexander GE, Crutcher MD. Functional architecture of basal ganglia circuits: neural substrates of parallel processing. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:266–271. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90107-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonini A, JSchwarz J, Oertel WH, Beer HF, Madeja UD, Leenders KL. [11C]raclopride and positron emission tomography in previously untreated patients with Parkinson's disease: Influence of L-dopa and lisuride therapy on striatal dopamine D2-receptors. Neurology. 1994;44:1325–1329. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.7.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey CH, Giustetto M, Huang YY, Hawkins RD, Kandel ER. Is heterosynaptic modulation essential for stabilizing Hebbian plasticity and memory? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2000;1:11–20. doi: 10.1038/35036191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breier A, Su TP, Saunders R, Carson RE, Kolachana BS, de Bartolomeis A, Weinberger DR, Weisenfeld N, Malhotra AK, Eckelman WC, Pickar D. Schizophrenia is associated with elevated amphetamine-induced synaptic dopamine concentrations: evidence from a novel positron emission tomography method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2569–2574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breitenstein C, Korsukewitz C, Floel A, Zwitserlood P, Knecht S. Neuropsychopharmacology. epub ahead of print, July 26th. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks DJ. Functional imaging studies on dopamine and motor control. J Neural Transm. 2001;108:1283–1298. doi: 10.1007/s007020100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunton S. A comprehensive approach to Parkinson's disease. How to manage fluctuating motor and nonmotor symptoms. Postgrad Med. 2006;119:55–64. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2006.06.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butefisch CM, Davis BC, Sawaki L, Waldvogel D, Classen J, Kopylev L, Cohen LG. Modulation of use-dependent plasticity by d-amphetamine. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:59–68. doi: 10.1002/ana.10056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butefisch CM, Davis BC, Wise SP, Sawaki L, Kopylev L, Classen J, Cohen LG. Mechanisms of use-dependent plasticity in the human motor cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3661–3665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050350297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carson RE, Breier A, de Bartolomeis A, Saunders RC, Su TP, Schmall B, Der MG, Pickar D, Eckelman WC. Quantification of amphetamine-induced changes in [11C]raclopride binding with continuous infusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:437–447. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199704000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casey BJ, Tottenham N, Fossella J. Clinical, imaging, lesion, and genetic approaches toward a model of cognitive control. Dev Psychobiol. 2002;40:237–254. doi: 10.1002/dev.10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cepeda C, Radisavljevic Z, Peacock W, Levine MS, Buchwald NA. Differential modulation by dopamine of responses evoked by excitatory amino acids in human cortex. Synapse. 1992;1:330–341. doi: 10.1002/syn.890110408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen R, Classen J, Gerloff G, Celnik P, Wassermann EM, Hallett M, Cohen LG. Depression of motor cortex excitability by low-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurology. 1997;48:1398–1403. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chibnall JT, Tait RC. Pain assessment in cognitively impaired and unimpaired older adults: a comparison of four scales. Pain. 2001;92:173–186. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00485-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Classen J, Liepert J, Wise SP, Hallett M, Cohen LG. Rapid plasticity of human cortical movement representation induced by practice. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1117–1123. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cropley VL, Fujita M, Innis RB, Nathan PJ. Molecular imaging of the dopaminergic system and its association with human cognitive function. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:898–907. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Keyser J, de Backer JP, Vauquelin G, Ebinger G. The effect of aging on the D1 dopamine receptors in human frontal cortex. Brain Res. 1990;528:308–310. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de la Fuente-Fernandez R, Sossi V, Huang Z, Furtado S, Lu JQ, Calne DB, Ruth TJ, Stoessl AJ. Levodopa-induced changes in synaptic dopamine levels increase with progression of Parkinson's disease: implications for dyskinesias. Brain. 2004;127:2747–2754. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deichmann R, Good CD, Josephs O, Ashburner J, Turner R. Optimization of 3-D MP-RAGE sequences for structural brain imaging. Neuroimage. 2000;12:112–127. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deisseroth K, Bito H, Schulman H, Tsien RW. Synaptic plasticity: A molecular mechanism for metaplasticity. Curr Biol. 1995;5:1334–1338. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doya K, Sejnowski TJ. A novel reinforcement model of birdsong vocalization learning. In: Tesauro G, Touretzky DS, Leen TK, editors. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Vol. 7. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1995. pp. 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emborg ME, Ma SY, Mufson EJ, Levey AI, Taylor MD, Brown WD, Holden JE, Kordower JH. Age-related declines in nigral neuronal function correlate with motor impairments in rhesus monkeys. J Comp Neurol. 1998;401:253–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson's disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114:2283–2301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feeney DM, de Smet AM, Rai S. Noradrenergic modulation of hemiplegia: facilitation and maintenance of recovery. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2004;22:175–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fiorillo CD. The uncertain nature of dopamine. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:122–123. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Floel A, Breitenstein C, Hummel F, Celnik P, Gingert C, Sawaki L, Knecht S, Cohen LG. Dopaminergic influences on formation of a motor memory. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:121–130. doi: 10.1002/ana.20536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Floel A, Hummel F, Breitenstein C, Knecht S, Cohen LG. Dopaminergic effects on encoding of a motor memory in chronic stroke. Neurology. 2005;65:472–474. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172340.56307.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Floel A, Nagorsenv U, Werhahn KJ, Ravindran S, Birbaumer N, Knecht S, Cohen LG. Influence of somatosensory input on motor function in patients with chronic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:206–212. doi: 10.1002/ana.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folstein MF. LuriaR Reliability, validity, and clinical application of the Visual Analogue Mood Scale. Psychol Med. 1973;3:479–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700054283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garris PA, Wightman RM. Different kinetics govern dopaminergic transmission in the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and striatum: an in vivo voltammetric study. J Neurosci. 1994;14:442–450. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00442.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giorgi O, de Montis G, Porceddu ML, Mele S, Calderini G, Toffano G, Biggio G. Developmental and age-related changes in D1-dopamine receptors and dopamine content in the rat striatum. Brain Res. 1987;432:283–290. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(87)90053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldman WP, Baty JD, Buckles VD, Sahrmann S, Morris JC. Cognitive and motor functioning in Parkinson disease: subjects with and without questionable dementia. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:674–680. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.5.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Good CD, Johnsrude IS, Ashburner J, Henson RN, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RS. A voxel-based morphometric study of ageing in 465 normal adult human brains. Neuroimage. 2001;14:21–36. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graybiel AM. The basal ganglia and chunking of action repertoires. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1998;70:119–136. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1998.3843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gresham GE, Fitzpatrick TE, Wolf PA, McNamara PM, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. Residual disability in survivors of stroke--the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:954–956. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197511062931903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hedden T, Gabrieli JD. Insights into the ageing mind: a view from cognitive neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:87–96. doi: 10.1038/nrn1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jay TM. Dopamine: a potential substrate for synaptic plasticity and memory mechanisms. Prog Neurobiol. 2003;69:375–390. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(03)00085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jouvenceau A, Dutar P, Billard JM. Alteration of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic responses in CA1 area of the aged rat hippocampus: contribution of GABAergic and cholinergic deficits. Hippocampus. 1998;8:627–637. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:6<627::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaasinen V, Vilkman H, Hietala J, Nagren K, Helenius H, Olsson H, Farde L, Rinne J. Age-related dopamine D2/D3 receptor loss in extrastriatal regions of the human brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:683–688. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kandel ER. The molecular biology of memory storage: a dialogue between genes and synapses. Science. 2001;294:1030–1038. doi: 10.1126/science.1067020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kandel ER, Pittenger C. The past, the future and the biology of memory storage. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;354:2027–2052. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knecht S, Breitenstein C, Bushuven S, Wailke S, Kamping S, Floel A, Zwitserlood P, Ringelstein EB. Levodopa: faster and better word learning in normal humans. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:20–26. doi: 10.1002/ana.20125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laruelle M. Imaging synaptic neurotransmission with in vivo binding competition techniques: a critical review. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:423–451. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200003000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li SC, Sikstrom S. Integrative neurocomputational perspectives on cognitive aging, neuromodulation, and representation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2002;26:795–808. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luo Y, Roth GS. The roles of dopamine oxidative stress and dopamine receptor signaling in aging and age-related neurodegeneration. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:449–460. doi: 10.1089/15230860050192224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marenco S, Carson RE, Berman KF, Herscovitch P, Weinberger DR. Nicotine-induced dopamine release in primates measured with [11C]raclopride PET. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:259–268. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martin SJ, Grimwood PD, Morris RG. Synaptic plasticity and memory: an evaluation of the hypothesis. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:649–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinsson L, Wahlgren NG, Hardemark HG. Amphetamines for improving recovery after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:CD002090. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mawlawi O, Martinez D, Slifstein M, Broft A, Chatterjee R, Hwang DR, et al. Imaging human mesolimbic dopamine transmission with positron emission tomography: I. Accuracy and precision of D(2; receptor parameter measurements in ventral striatum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1034–1057. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200109000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nutt JG, Fellman JH. Pharmacokinetics of levodopa. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1984;7:35–49. doi: 10.1097/00002826-198403000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9:97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Otani S, Blond O, Desce JM, Crepel F. Dopamine facilitates long-term depression of glutamatergic transmission in rat prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 1998;85:669–676. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00677-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riedel-Heller SG, Busse A, Angermeyer MC. The state of mental health in old-age across the ‘old’ European Union-- a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:388–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robertson DR, Wood ND, Everest H, Monks K, Waller DG, Renwick AG, George CF. The effect of age on the pharmacokinetics of levodopa administered alone and in the presence of carbidopa. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;28:61–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rossini PM, Barker AT, Berardelli A, Caramia MD, Caruso G, Cracco RQ, et al. Non-invasive electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, spinal cord and roots: basic principles and procedures for routine clinical application. Report of an IFCN committee. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1994;91:79–92. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rossini PM, Calautti C, Pauri F, Baron JC. Post-stroke plastic reorganisation in the adult brain. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:493–502. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00485-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roth GS, Joseph JA, Mason RP. Membrane alterations as causes of impaired signal transduction in Alzheimer's disease and aging. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:203–206. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93902-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sawaki L, Yaseen Y, Kopylev L, Cohen LG. Age-dependent changes in the ability to encode a novel elementary motor memoryv. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:521–524. doi: 10.1002/ana.10529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scheidtmann K, Fries W, Muller F, Koenig E. Effect of levodopa in combination with physiotherapy on functional motor recovery after stroke: a prospective, randomised, double-blind study. Lancet. 2001;358:787–790. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05966-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schlosser R, Brodie JD, Dewey SL, Alexoff D, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, et al. Long-term stability of neurotransmitter activity investigated with 11C-raclopride PET. Synapse. 1998;28:66–70. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199801)28:1<66::AID-SYN8>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schultz W, Tremblay L, Hollerman JR. Reward processing in primate orbitofrontal cortex and basal ganglia. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:272–284. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Strafella AP, Ko JH, Grant J, Fraraccio M, Monchi O. Corticostriatal functional interactions in Parkinson's disease: a rTMS/[11C]raclopride PET study. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2946–2952. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Strafella AP, Paus P, Barrett J, Dagher A. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human prefrontal cortex induces dopamine release in the caudate nucleus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC157. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-j0003.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Strafella A, Paus P, Fraraccio M, Dagher A. Striatal dopamine release induced by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human motor cortex. Brain. 2003;126:2609–2615. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taub E, Uswatte G, Elbert T. New treatments in neurorehabilitation founded on basic research. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:228–236. doi: 10.1038/nrn754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tedroff J, Aquilonius SM, Hartvig PG, Langstrom B. Functional positron emission tomographic studies of striatal dopaminergic activity. Changes induced by drugs and nigrostriatal degeneration. Adv Neurol. 1996;69:443–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tedroff J, Pedersen M, S.M. Aquilonius SM, Hartvig PG, Jacobsson G, Langstrom B. Levodopa-induced changes in synaptic dopamine in patients with Parkinson's disease as measured by [11C]raclopride displacement and PET. Neurology. 1996;46:1430–1436. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.5.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Volkow ND, Gur RC, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Moberg PJ, Ding YS, et al. Association between decline in brain dopamine activity with age and cognitive and motor impairment in healthy individuals. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:344–349. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Walker-Batson D, Smith P, Curtis S, Unwin DH. Neuromodulation paired with learning dependent practice to enhance post stroke recovery? Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2004;22:387–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ward NS, Cohen LG. Mechanisms underlying recovery of motor function after stroke. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1844–1848. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.12.1844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Watabe H, Endres CJ, Breier A, Schmall B, Eckelman WC, Carson RE. Measurement of dopamine release with continuous infusion of [11C]raclopride: optimization and signal-to-noise considerations. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Whitall J, McCombe S, Waller S, Silver KH, Macko RF. Repetitive bilateral arm training with rhythmic auditory cueing improves motor function in chronic hemiparetic stroke. Stroke. 2000;31:2390–2395. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.10.2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wickens JK. Cellular models of reinforcement. In: Houk J, Davis C, Beiser JL, editors. Models of information processing in the basal ganglia. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1995. pp. 187–214. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Williams GV, Goldman-Rakic PS. Modulation of memory fields by dopamine D1 receptors in prefrontal cortex. Nature. 1995;376:572–575. doi: 10.1038/376572a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Williams SM, Goldman-Rakic PS. Characterization of the dopaminergic innervation of the primate frontal cortex using a dopamine-specific antibody. Cereb Cortex. 1993;3:199–222. doi: 10.1093/cercor/3.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wise RA. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:483–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wong DF, Young D, Wilson PD, Meltzer CC, A. Gjedde A. Quantification of neuroreceptors in the living human brain: III. D2-like dopamine receptors: theory, validation, and changes during normal aging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17:316–330. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199703000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Woods RP, J. Mazziotta C, Cherry SR. MRI-PET registration with automated algorithm. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17:536–546. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ziemann U, Tergau F, Bruns D, Baudewig J, Paulus W. Changes in human motor cortex excitability induced by dopaminergic and anti-dopaminergic drugs. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1997;105:430–437. doi: 10.1016/s0924-980x(97)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]