Abstract

Activation of the cysteine protease caspase-8 by the death receptor Fas (CD95/APO-1) in B lymphoblastoid SKW6.4 cells or Jurkat T cells is associated with GSH depletion. Conversely, GSH depletion by the aldehyde acrolein (3–30 μM) was associated with inhibition of Fas-induced caspase-8 activation, although GSH depletion by buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) did not affect caspase-8 activation. In contrast to BSO, acrolein caused a loss of caspase-8 cysteine content in association with direct alkylation of caspase-8. Our findings indicate that inhibition of caspase-8 by thiol-reactive agents such as acrolein is not due to GSH depletion but caused by direct protein thiol modifications.

1. Introduction

The death receptor Fas (CD95/APO-1), a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily, is involved in immune system homeostasis and mediates cell apoptosis in response to extrinsic stimuli by initial activation of the cysteine protease caspase-8 (FLICE/MACHα1/Mch5). The mechanism of caspase-8 activation is cell type-dependent (1), and is rapid in type I cells in which it occurs primarily at the death-inducing signaling complex (DISC), resulting in subsequent activation downstream caspases independent of mitochondrial activation. Alternatively, Fas-mediated apoptosis in type II cells relies more on mitochondrial pathways, and caspase-8 activation occurs more slowly and is largely amplified by mitochondrial perturbations.

Numerous previous studies have indicated that oxidative events mediate apoptosis, either by activation of caspase cascades through mitochondria-dependent pathways or by more direct activation of death receptors such as Fas (2,3). Accordingly, a common feature of cell apoptosis is depletion of the cellular antioxidant GSH (4). Consistent with the suggested role of GSH in preventing oxidative mechanisms of apoptosis are observations that resistance against Fas-induced apoptosis in certain cell types is associated with elevated cellular GSH levels, and that depletion of cellular GSH can eliminate the resistant phenotype (5,6).

However, the relationship between cellular GSH status and caspase-8 activation and apoptosis is controversial, and conflicting reports exist in the literature. First, depletion of cellular GSH during apoptosis is not due to its oxidation, but is caused primarily by active GSH efflux, and inhibition of GSH efflux can prevent apoptosis (4,7). Furthermore, several recent studies have indicated that decreases in cellular GSH negatively affect caspase-8 activation (8,9), presumably related to the fact that caspase-8 (as well as other caspases) contain redox-sensitive critical cysteine residues and therefore require reducing cellular conditions for optimal activity (9,10). Accordingly, cell exposure to thiol-reactive substances, such as the α,β-unsaturated aldehydes acrolein or 4-hydroxynonenal, can inhibit caspase activation and apoptosis in close association with depletion of cellular GSH (11,12).

The present studies were designed to further clarify the relationship between cellular GSH status and Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation, as well as the mechanisms by which the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde acrolein, an important environmental pollutant and product of biological oxidation (13), affects caspase-8 activation. Because of suggested differences in GSH regulation of Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation in different cell types (5), we investigated the consequences of changes in cellular GSH status on Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation in both SKW6.4. B lymphoblastoid (type I) cells and Jurkat T (type II) cells. Our results indicate that GSH depletion following Fas stimulation occurs primarily in type I cells, as a result of caspase-8 activation. In addition, we report that inhibition of caspase-8 activation by acrolein is not a direct result of GSH depletion or cellular oxidant production, but is instead associated with direct caspase-8 alkylation and modification of its cysteine residues.

Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture and treatments

The B lymphoblastoma cell line SKW6.4 was obtained from ATCC, and propagated in RPMI 1640 medium (ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Jurkat T cells (ATCC) were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM pyruvate and 10 μg/ml folate (14). For experiments, cells were suspended at 2 x 106 cells/ml, treated with the appropriate reagents, and harvested after various incubation periods for analysis of caspase-8 activation. Treatments with acrolein (Sigma) were performed in cell suspensions in HBSS, to avoid unwanted side reactions of acrolein with culture media constituents, for up to 30 min (allowing completion of acrolein reactions with cell components). For further incubation and cell activation, HBSS was replaced regular RPMI media. Control treatments (0 μM acrolein) involved similar HBSS treatment and media exchanges. All reagents used were from Sigma unless otherwise indicated.

2.2. Analysis of caspase-8 cleavage and activity

Following cell incubations, cells (2 x 106/ml) were lysed in 75 μl lysis buffer (250 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, 2 mM Na3VO4, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, and 10 μg/ml of aprotinin and leupeptin), and full length and cleaved (activated) caspase-8 (p43/p41) were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using a mAb against caspase-8 (1C12; Cell Signaling). Antibody binding was detected using HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling) and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce). Caspase-8 activity was also determined using a fluorimetric assay with IETD-AFC as substrate (R&D Systems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Analysis of cellular GSH

For analysis of cellular GSH, cell lysates were immediately derivatized with monobromobimane (mBrB; Calbiochem), and GSH-mBrB was analyzed by HPLC with fluorescence detection (13). Alternatively, GSH and GSSG were analyzed simultaneously as dansyl derivatives by HPLC and fluorescence detection, as detailed previously (15).

2.4. Cellular peroxide production

Cells were pre-incubated with (10 μM) 2’,7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) for 30 min, and treated with acrolein (1–30 μM) for an additional 30 min. In some cases, cells were pretreated with 100 μM BSO, 24 hrs, prior to DCF-DA. After washing with PBS, fluorescence was analyzed using flow cytometry. Results were based on a minimum of 10,000 counted cells, and staining with propidium iodide was used to gate out dead cells.

2.5 Analysis of protein modifications using biotin labeling and avidin chromatography

Protein cysteine residues were labeled by lysing treated or untreated SKW6.4 or Jurkat T cells (20 x 106) in 500 μl lysis buffer containing 50 μM of the thiol-specific reagent EZ-link Maleimide-PEO2-Biotin (Pierce), and 1 hr incubation at RT. Alternatively, biotin labeling of protein aldehyde adducts was performed by adding 22.5 μl biotin hydrazide (Pierce; 100 mM in DMSO) to cell lysates (20 x 106 cells in 500 μl), and 2 hr incubation at RT after which 450 μl NaBH4 (30 mM in PBS) was added (16). In both cases, unreacted biotinylating agent was subsequently removed by gel filtration on Sephadex G-25 columns (PD-10; Amersham), and collected protein fractions (monitored by UV absorbance at 280 nm) were applied to a column packed with 2 ml Ultralink Immobilized Monomeric Avidin (Pierce) equilibrated with buffer A (0.1 M Na2HPO4, 0.15 M NaCl; pH 7.2). After sample application, columns were washed with Buffer A until the absorbance at 280 nm reached baseline, and biotinylated proteins were eluted with 4 mM D-biotin in Buffer A. To optimize elution of biotinylated proteins, the pump was stopped for 5 min during this elution step. Collected protein fractions were concentrated to about 100 μl using Amicon Ultra4 10kDa filters (Millipore), and proteins were then precipitated with 10% TCA and resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer for analysis by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting using mAbs against caspase-8 or caspase-3 (Cell Signaling).

3. Results

3.1. Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation causes GSH depletion

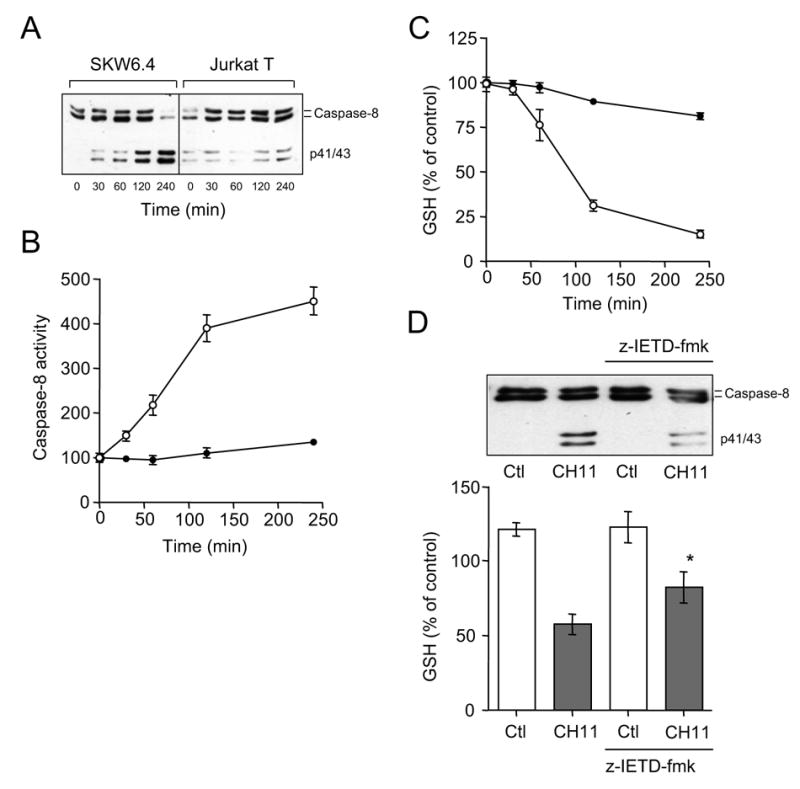

We first evaluated the kinetics of Fas/CD95-mediated caspase-8 activation in relation to alterations in cellular GSH status, in both SKW6.4 (type I) cells and Jurkat T (type II) cells (1). Consistent with earlier findings (1), Fas stimulation with anti-Fas IgM CH11 (100 ng/ml; Upstate) caused rapid pro-caspase-8 cleavage and caspase-8 activation in SKW6.4 cells, while this was less pronounced and more delayed in Jurkat T cells (Fig. 1A and B). Analysis of cellular GSH revealed that Fas stimulation resulted in depletion of cellular GSH, as reported previously (4). Consistent with these earlier findings, this depletion was not associated with increased formation of GSSG, but due to GSH efflux into the media (not shown). Fas-mediated GSH efflux was more pronounced in SKW6.4 cells compared to Jurkat T cells (Fig. 1C). Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation and GSH depletion appeared to be closely associated, but caspase-8 activation was found to precede GSH depletion. While caspase-8 activation was detectable after 30 min (Fig 1A and B), GSH levels did not decrease until about 60 min after Fas stimulation (Fig. 1C). In addition, Fas-mediated GSH depletion was significantly reduced when caspase-8 activation was inhibited using the caspase-8 inhibitor, z-IETD-fmk (20 μM; Calbiochem; Fig. 1D). Hence, GSH efflux following Fas stimulation appears to be a consequence of caspase-8 activation, and occurs primarily in type I cells in which caspase-8 activation is primarily associated with DISC assembly (1,5).

Figure 1.

Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation and GSH depletion in type I and type II cells. A: Time-dependent cleavage of caspase-8 upon Fas stimulation with CH11 (100 ng/ml) in SKW6.4 (type I) or Jurkat T (typeII) cells. B: Time-dependent increase in Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation SKW6.4 (○) or Jurkat T (●) cells, analyzed using the fluorogenic substrate IETD-AFC (mean ± S.D.; n = 3). C: Analysis of cellular GSH following Fas-stimulation of SKW6.4 (○) or Jurkat T (●) cells. GSH concentrations are expressed relative to initial concentrations (36 ± 6 and 56 ± 9 nmol/mg protein in SKW6.4 and Jurkat T cells, respectively; mean ± S.D., n = 3). D: Effect of the caspase-8 inhibitor z-IETD-fmk (20 μM; 15 min pre-incubation) on Fas-mediated GSH depletion in SKW6.4 cells (mean ± S.D., n = 3; *: p<0.05 compared to corresponding control; unpaired t-test).

3.2. Effect of GSH depletion on caspase-8 activation

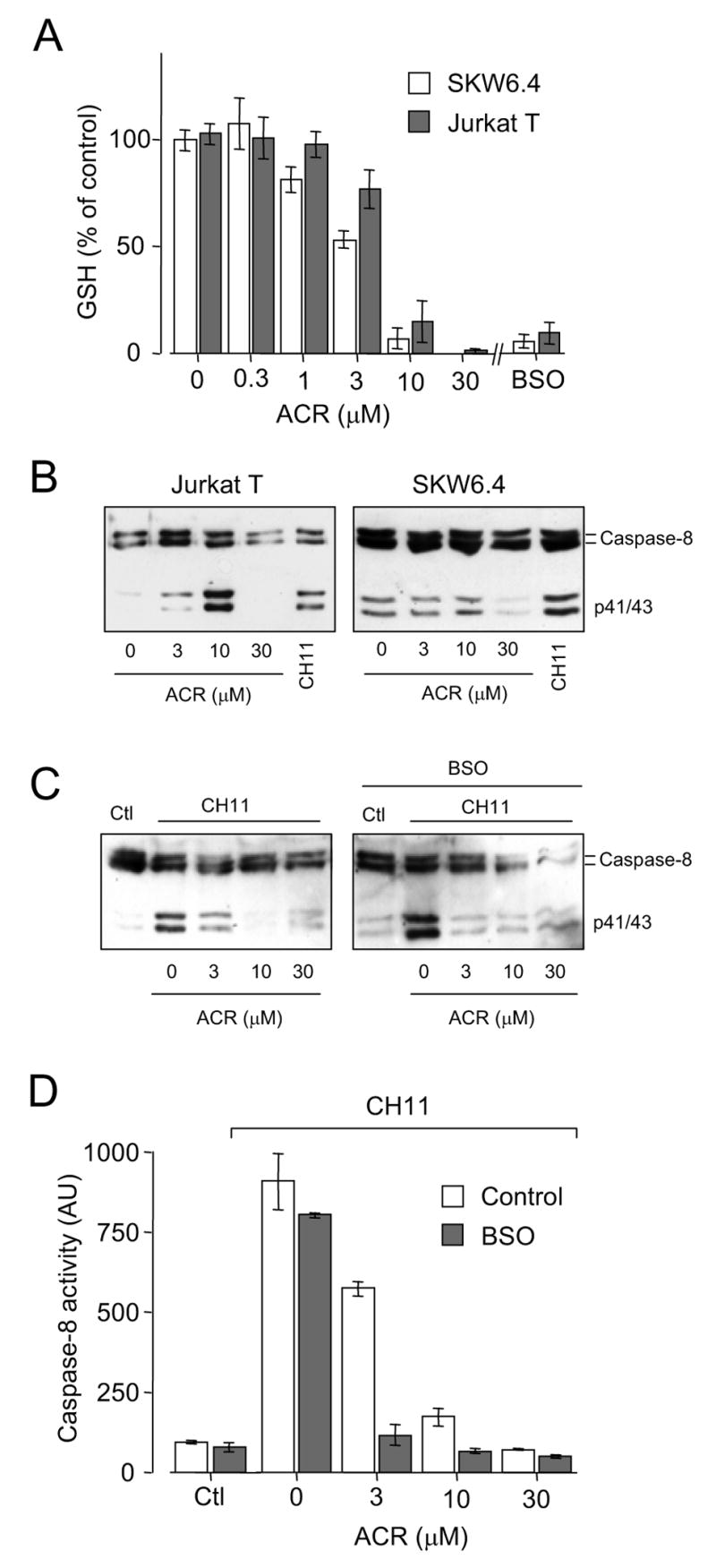

To further examine the relationship between GSH depletion and caspase-8 activation, we used two independent approaches to deplete cellular GSH. First, exposure of either SKW6.4 or Jurkat cells to the α,β-unsaturated aldehyde acrolein, an important environmental pollutant and an endogenous product of several oxidative processes (17,18), causes a rapid (within 10 min) decrease in cellular GSH at concentrations >1 μM (Fig. 2A). This GSH depletion is largely due to direct or GST-catalyzed GSH conjugation and elimination, and is not associated with significant oxidation to GSSG (13,19). Second, cells were pre-incubated with the GSH synthesis inhibitor buthionine sulfoximine (BSO; 100 μM; Sigma), which causes gradual and persistent depletion of cellular GSH, to 5.5 ± 2.9 and 10.4 ± 4.9% of initial levels (in SKW6.4 cells and Jurkat T cells, respectively) after 24 hrs, comparable to the extent of GSH depletion by 10–30 μM acrolein (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

GSH depletion and regulation of caspase-8 activation by acrolein and BSO. A: Effect of 30 min pre-treatment with indicated concentrations of acrolein on GSH levels in SKW6.4 cells (open bars) and Jurkat T cells (shaded bars). Alternatively, cells were pre-incubated with 100 μM BSO for 24 hrs, prior to GSH analysis (mean ± S.D., n = 3). B: Dose-dependent effect of acrolein on caspase-8 cleavage in SKW6.4 or Jurkat T cells. Cells were treated with acrolein for 30 min, and subsequently incubated in RPMI for an additional 3.5 hrs before lysis. C: Effect of cell pre-treatment of with indicated concentrations of acrolein (ACR; 30 min in HBSS) on CH11-induced caspase-8 cleavage, measured after 4 hrs by Western blot analysis, in untreated SKW6.4 cells (left panel) or cells that were pretreated with 100 μM BSO (100 μM; 24 hrs; right panel). D: Measurement of CH-11-induced caspase-8 activity in SKW6.4 cells, after cell exposure to acrolein (30 min in HBSS) or BSO using treatment conditions as in panel C. Mean data ± S.D. (n = 3) are presented for control cells (no BSO; open bars) or cells that were pre-incubated with BSO (100 μM, 24 hrs; shaded bars).

Analogous to previous results in neutrophils (13), exposure of Jurkat T cells to acrolein biphasically affected pro-caspase-8 activation. Low concentrations (1–10 μM) enhanced caspase-8 cleavage, whereas higher concentrations (>10 μM) were markedly inhibitory (Fig. 2B). Similar treatment of SKW6.4 cells did not result in significant caspase-8 activation, but primarily showed inhibition of caspase-8 cleavage at concentrations >10 μM. Given previous reports indicating that acrolein can stimulate apoptosis by mitochondrial pathways (20), the ability of acrolein to activate caspase-8 would be expected to be more prominent in type II cells (e.g. Jurkat T) than in type I cells (e.g. SKW6.4) (1,9).

Pretreatment of either SKW6.4 cells (Fig. 2C and D) or Jurkat T cells (not shown) with acrolein was found to dramatically and dose-dependently inhibit Fas-mediated caspase-8 cleavage (Fig. 2C) and activity (Fig. 2D). Analogous to previous findings (13), this inhibitory effect of acrolein on caspase-8 activation corresponded closely with the extent of GSH depletion (Fig. 2A), suggesting a redox-dependent mechanism of caspase-8 inactivation. However, in contrast to the effects of acrolein, comparable depletion of GSH by pre-incubation with BSO did not result in significant activation of caspase-8 nor did it prevent Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation, in either SKW6.4 cells (Fig. 2D) or Jurkat T cells (not shown). Western blot analysis of caspase-8 cleavage suggested a slight activation following pretreatment with BSO (Fig. 2C), which may be consistent with previous observations of increased caspase-8 association with DISC complexes after GSH depletion (5). However, no increase in basal or Fas-stimulated caspase-8 activity was observed following BSO pre-incubation (Fig. 2D), perhaps due to some oxidative inactivation of proteolytically activated caspase-8 in BSO-treated cells. Although depletion of cellular GSH by BSO pre-incubation did in itself not inhibit Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation, BSO pretreatment markedly potentiated the inhibitory effects of acrolein on Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation in both SKW6.4 cells (Fig. 2C and D) and Jurkat T cells (not shown).

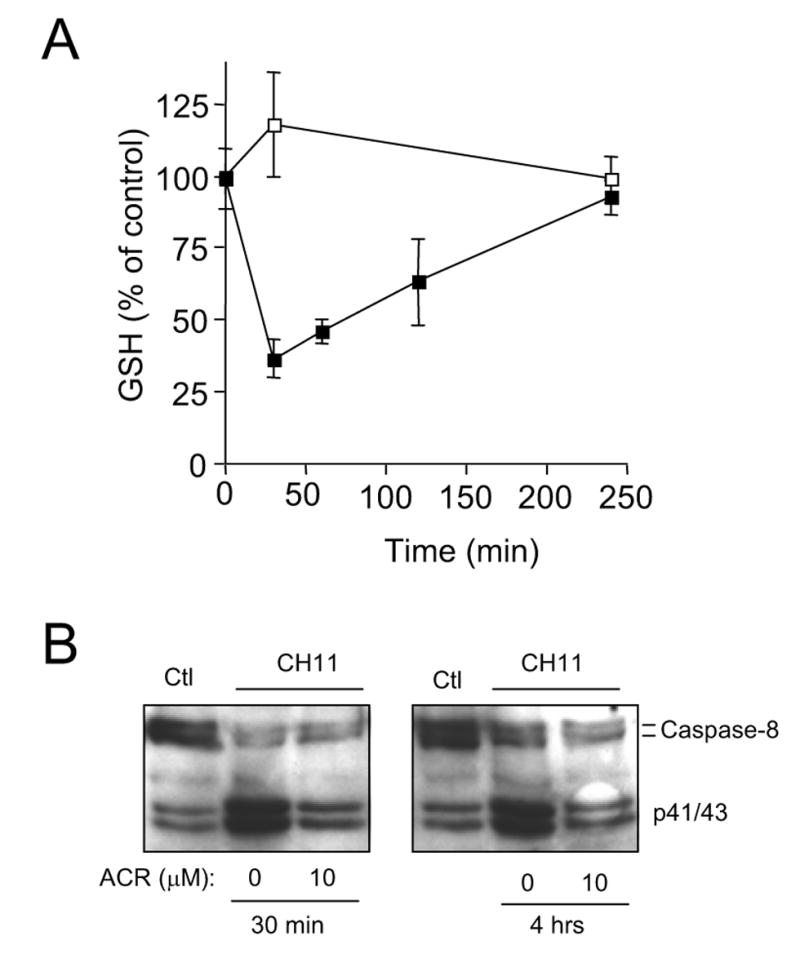

Whereas the decrease in cellular GSH after Fas stimulation was gradual and persistent (Fig. 1), GSH depletion in SKW6.4 cells by acrolein was rapid and was reversible over time, and GSH levels were completely restored to initial levels after 4 hrs post-incubation (Fig. 3A), consistent with earlier observations (21). Nearly identical results were obtained with Jurkat T cells (data not shown). In contrast to the reversal of acrolein-induced GSH depletion, the inhibitory effect of acrolein pretreatment on Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation was more persistent, even after a 4 hrs recovery period between SKW6.4 cell exposure to acrolein and Fas stimulation (Fig. 3B). Thus, inhibition of caspase-8 activation by acrolein does not appear to be directly related to GSH depletion, but may be due to more irreversible modifications, perhaps within caspase-8 itself.

Figure 3.

Reversibility of acrolein-induced GSH depletion and caspase-8 inhibition. A: Time-dependent recovery of acrolein-induced GSH depletion in SKW6.4 cells. Cells were treated with HBSS with (■) or without (□) 10 μM acrolein for 30 min, and subsequently incubated in RPMI medium for up to 4 hrs, before lysis and analysis of cellular GSH (mean ± S.D., n = 3). B: SKW6.4 cells were pre-incubated with acrolein (30 min in HBSS) and stimulated either immediately with CH11 (left panel) or after 4 hr recovery in RPMI media prior to CH11 stimulation (right panel).

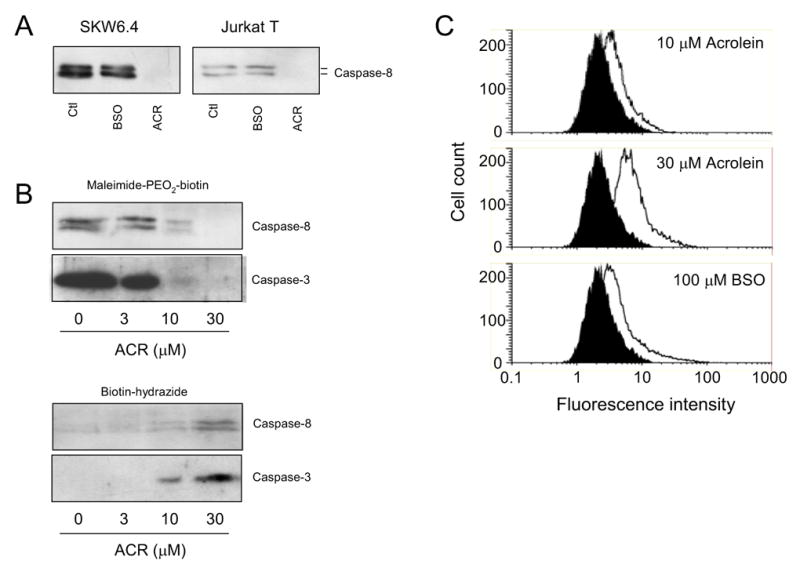

3.3. Acrolein directly targets caspase-8 cysteine residues

To directly demonstrate modifications within caspase-8 under these various experimental conditions, SKW6.4 cells or Jurkat T cells were lysed in the presence of the cysteine-labeling agent biotin-PEO-maleimide, following cell exposure to either acrolein or BSO. As expected, Western blot analysis of biotinylated proteins obtained from untreated SKW6.4 cells or Jurkat T cells revealed the presence of caspase-8 (Fig. 4A), indicating the presence of reduced cysteine residues within caspase-8. Similar levels of biotinylated caspase-8 were detected in cells that were treated with BSO for 24 hrs, indicating that the cysteine content of caspase-8 was not significantly affected even after >90% depletion of cellular GSH. In contrast, almost no biotinylated caspase-8 was detected from similarly derivatized SKW6.4 cells or Jurkat T cells after exposure to 30 μM acrolein (Fig. 4A), indicating that the caspase-8 cysteine content was dramatically reduced. As shown in Fig. 4B, the decrease in caspase-8 cysteine content by acrolein was dose-dependent (Fig. 4B), and closely parallels cell depletion of GSH (Fig. 2A). However, the fact that comparable GSH depletion after cell treatment with BSO did not significantly affect caspase-8 cysteine status indicates that GSH depletion was not responsible for caspase-8 modification by acrolein.

Figure 4.

Acrolein induces direct caspase modifications. A: SKW6.4 cells or Jurkat T cells were incubated with BSO (100 μM; 24 hrs) or acrolein (30 μM in HBSS; 30 min) and cysteine-containing proteins were labeled using Maleimide-PEO2-Biotin labeling during cell lysis. Affinity-purified biotinylated proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis for caspase-8. B: Dose-dependent loss of cysteine content in caspases-8 and –3 in acrolein-treated SKW6.4 cells (analyzed as in A) in relation to the formation of protein-aldehyde adducts (determined by labeling with biotin hydrazide and purification by avidin chromatography). Data are representative of at least 2 separate experiments. C: Analysis of cellular oxidant production after exposure to acrolein or after GSH depletion by BSO. SKW6.4 cells (2 x 106/ml) were preincubated with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 30 min, and then treated with acrolein for an additional 30 min, after which DCF fluorescence was analyzed by flow cytometry. Cell treatment with BSO was for 24 hrs prior to DCFH-DA loading. Representative data from 3 experiments are shown.

One of the main reactions of acrolein or related aldhydes with proteins is via direct modification of susceptible cysteine residues to form a Michael-type thioether-linked aldehyde adduct (22–24). To demonstrate the presence protein-aldehyde adducts within caspase-8 of acrolein-treated cells, we used biotin hydrazide derivatization and avidin chromatography to collect aldehyde-adducted proteins from cell lysates (16), and analyzed these for the presence of caspase-8. Although little caspase-8 was detectable in biotin hydrazide-derivatized proteins from untreated cells, increasing amounts of caspase-8 were observed in lysates of cells that were exposed to 3–30 μM acrolein (Fig. 4B). Moreover, the extent of biotin hydrazide reactivity of caspase-8 was inversely related to decreased cysteine content, as demonstrated with biotin-PEO-maleimide labeling, strongly suggesting that acrolein formed aldehyde conjugates within caspase-8 through alkylation of its cysteine residues. Because acrolein is likely to target other cysteine-containing proteins in addition to caspase-8, including other caspases, we also probed biotin-PEO-maleimide- and biotin hydrazide-labeled proteins for the presence of caspase-3, after the various cell treatments. Indeed, as demonstrated in Fig. 4B, acrolein also dose-dependently reduced the cysteine content of caspase-3, and this was similarly associated with corresponding increases of aldehyde adducts in this protein, consistent with direct alkylation of caspase-3 cysteine residues.

Acrolein and related unsaturated aldehydes are known to be capable of enhancing cellular oxidant production (25,26), and could therefore potentially inactivate caspase-8 by more indirect oxidative mechanisms. To address this, we analyzed cellular oxidant production in SWK6.4 cells following treatment with acrolein and after pretreatment with BSO. As shown in Fig. 4C, acrolein exposure caused dose-dependent increase in cellular oxidant production (mean DCF fluorescence intensity increased from 3.2 ± 0.4 to 4.1 ± 0.7, 5.7 ± 0.8, and 9.6 ± 3.4, after treatment with 3, 10 and 30 μM acrolein, respectively; mean ± S.E., n=3). Cell pre-incubation with BSO also significantly increased DCF fluorescence, to an extent comparable to that following exposure to 10 μM acrolein (mean DCF fluorescence 6.9 ± 1.5 vs 5.7 ± 0.8; Fig. 4C). Since, only acrolein treatment but not BSO pre-incubation resulted in significant loss of caspase-8 cysteine content (Fig. 4A and B), production of cellular oxidant is unlikely to account for the observed caspase-8 thiol loss and alkylation by acrolein.

4. Discussion

Consistent with earlier reports (4,7), our results demonstrate that Fas stimulation results in GSH depletion due to GSH efflux. Fas-mediated GSH depletion was more prominent in type I compared to type II cells, and was found to occur in response to caspase-8 activation. Observations that inhibitors of GSH efflux prevent some features of apoptosis (7,27) indicate that GSH depletion is necessary for appropriate execution of apoptosis. However, the cellular mechanisms by which activation of caspase-8 and/or downstream caspases promote GSH efflux still remain to be clarified. Although GSH depletion upon Fas stimulation is not responsible for caspase activation, a number of studies have claimed that Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation and apoptosis may be intimately linked with GSH status (5,6,8,9). The present study partly dispels this notion, and demonstrates that Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation does not critically depend on cellular GSH levels per se. While cell exposure to the thiol-reactive aldehyde acrolein markedly affected caspase-8 activation in relation to GSH depletion, similar depletion of GSH by inhibition of its synthesis did not significantly affect caspase-8 activity. Indeed, the inhibitory effects of acrolein were uniquely associated with direct modification of cysteine residues within caspase-8, most likely through their alkylation.

Our findings are in apparent contrast with several previous studies that suggest that activation of caspase-8 is critically dependent on cellular GSH status (8,9). For example, Musallam and co-workers (8) noted increased resistance against Fas-induced apoptosis and caspase-8 after cell isolation and culture in association with reduced overall GSH levels. However, it is possible that additional cellular changes during cell culture, perhaps related to changes in GSH status, may have contributed to the observed resistance against apoptosis. Moreover, the relative modest changes in cellular GSH levels or GSH/GSSG ratio observed by Musallam et al. would seem insufficient to dramatically affect the cysteine status within caspase-8. Indeed, we observed no significant reduction in caspase-8 cysteine content even after 90% depletion of GSH with BS, perhaps because cellular redox status (GSH/GSSG ratio) was not dramatically affected.

Hentze et al. (9) reported that depletion of cellular GSH by a combination of BSO and alkylating agents prevented Fas-mediated caspase-8 activation at DISC complexes. Our current studies indicate that GSH depletion by BSO alone does not block caspase-8 activation, and that inhibition of caspase-8 activation following exposure to the alkylating agent acrolein was associated with direct alkylation of caspase-8 and modification of its cysteine residue(s). Hence, the ability of acrolein to inhibit caspase-8 activation appears to rely on direct protein modifications, rather than indirect cellular oxidant formation or other changes following depletion of GSH. Based on our findings, the inhibitory effects observed by Hentze et al. were most likely caused by direct modification of caspase-8 by the alkylating agents used. Alternatively, extensive and prolonged GSH depletion after combined exposure to BSO and thiol-reactive alkylating agents could have caused indirect oxidation of critical cysteines within caspase-8, but this was unfortunately not addressed by Hentze et al. The observed reversal of caspase-8 inhibition by subsequent addition of GSH (9) does not rule out direct thiol alkylation reactions which can also be reversible in the presence of thiols (22). In this regard, thio-ether adducts with acrolein are known to be relatively stable (22), consistent with the lack of reversal of caspase-8 inactivation even after 4 hr recovery period following acrolein treatment (Fig. 3).

Although our studies specifically address inhibitory effects of one thiol alkylating agent, acrolein, they may have more general implications for mechanisms by which caspases or other redox-sensitive signaling pathways are affected by cellular or environmental oxidants or thiol-reactive agents. Our findings suggest that such regulation most likely occurs by direct oxidation/alkylation of susceptible protein cysteine residues, rather than by indirect oxidative modifications in response to GSH depletion. Indeed, GSH depletion by BSO was found to be insufficient in regulating caspase activation, in the absence of active oxidant production or generation of alkylating agents. Although this concept has been generally accepted in the context of redox signaling by biological oxidants produced by e.g. Nox enzymes, it can be extended to biological signaling pathways initiated by reactive aldehydes (such as acrolein or hydroxynonenal) that can be generated in specific cellular regions as a result of localized oxidative events. In contrast to cellular reducing systems (e.g. glutaredoxins) that serve to reverse protein cysteine oxidation or thiolation, no specific enzymatic systems capable of reversing alkylation of reactive protein cysteine residues by acrolein or related electrophiles are known to exist. Thus, thiol modifications by acrolein or related aldehydes may be reversed primarily by protein turnover, or to slow dissociation of these adduct in the presence of GSH or other thiols (22). In addition, cell systems appear to rely largely on various detoxification systems that reduce unsaturated aldehydes such as acrolein (19,28,29), to minimize their ability to alkylate redox-sensitive protein targets such as caspase-8. Accordingly, depletion of cellular GSH should diminish GSH-dependent detoxicification of acrolein (19), and thereby allow acrolein to target and inactivate susceptible proteins such as caspase-8, as was observed in our studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Scott Tighe and Umadevi Wesley for their assistance with flow cytometry. This work was supported by NIH grants HL68865 and NH074295.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Scaffidi C, Fulda S, Srinivasan A, Friesen C, Li F, Tomaselli KJ, Debatin KM, Krammer PH, Peter ME. Two CD95 (APO-1/Fas) signaling pathways. Embo J. 1998;17:1675–1687. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang B, Hirahashi J, Cullere X, Mayadas TN. Elucidation of molecular events leading to neutrophil apoptosis following phagocytosis: cross-talk between caspase 8, reactive oxygen species, and MAPK/ERK activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28443–28454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasahara Y, Iwai K, Yachie A, Ohta K, Konno A, Seki H, Miyawaki T, Taniguchi N. Involvement of reactive oxygen intermediates in spontaneous and CD95 (Fas/APO-1)-mediated apoptosis of neutrophils. Blood. 1997;89:1748–1753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Dobbelsteen DJ, Nobel CS, Schlegel J, Cotgreave IA, Orrenius S, Slater AF. Rapid and specific efflux of reduced glutathione during apoptosis induced by anti-Fas/APO-1 antibody. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15420–15427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friesen C, Kiess Y, Debatin KM. A critical role of glutathione in determining apoptosis sensitivity and resistance in leukemia cells. Cell Death Differ 11 Suppl. 2004;1:S73–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiba T, Takahashi S, Sato N, Ishii S, Kikuchi K. Fas-mediated apoptosis is modulated by intracellular glutathione in human T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1164–1169. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghibelli L, Fanelli C, Rotilio G, Lafavia E, Coppola S, Colussi C, Civitareale P, Ciriolo MR. Rescue of cells from apoptosis by inhibition of active GSH extrusion. Faseb J. 1998;12:479–486. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.6.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musallam L, Ethier C, Haddad PS, Denizeau F, Bilodeau M. Resistance to Fas-induced apoptosis in hepatocytes: role of GSH depletion by cell isolation and culture. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G709–718. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00013.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hentze H, Schmitz I, Latta M, Krueger A, Krammer PH, Wendel A. Glutathione dependence of caspase-8 activation at the death-inducing signaling complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5588–5595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fadeel B, Ahlin A, Henter JI, Orrenius S, Hampton MB. Involvement of caspases in neutrophil apoptosis: regulation by reactive oxygen species. Blood. 1998;92:4808–4818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelstein EI, Ruben J, Koot CW, Hristova M, van der Vliet A. Regulation of constitutive neutrophil apoptosis by the alpha,beta-unsaturated aldehydes acrolein and 4-hydroxynonenal. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L1019–1028. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00227.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kern JC, Kehrer JP. Acrolein-induced cell death: a caspase-influenced decision between apoptosis and oncosis/necrosis. Chem Biol Interact. 2002;139:79–95. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(01)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkelstein EI, Ruben J, Koot CW, Hristova M, van der Vliet A. Regulation of constitutive neutrophil apoptosis by the {alpha},{beta}-unsaturated aldehydes acrolein and 4-hydroxynonenal. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005 doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00227.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson DJ, Alessandrini A, Budd RC. MEK1 activation rescues Jurkat T cells from Fas-induced apoptosis. Cell Immunol. 1999;194:67–77. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones DP, Carlson JL, Samiec PS, Sternberg P, Jr, Mody VC, Jr, Reed RL, Brown LA. Glutathione measurement in human plasma. Evaluation of sample collection, storage and derivatization conditions for analysis of dansyl derivatives by HPLC. Clin Chim Acta. 1998;275:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(98)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoo BS, Regnier FE. Proteomic analysis of carbonylated proteins in two-dimensional gel electrophoresis using avidin-fluorescein affinity staining. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:1334–1341. doi: 10.1002/elps.200405890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Holian A. Acrolein: a respiratory toxin that suppresses pulmonary host defense. Rev Environ Health. 1998;13:99–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kehrer JP, Biswal SS. The molecular effects of acrolein. Toxicol Sci. 2000;57:6–15. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/57.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berhane K, Widersten M, Engstrom A, Kozarich JW, Mannervik B. Detoxication of base propenals and other alpha, beta-unsaturated aldehyde products of radical reactions and lipid peroxidation by human glutathione transferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1480–1484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanel A, Averill-Bates DA. The aldehyde acrolein induces apoptosis via activation of the mitochondrial pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1743:255–267. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horton ND, Biswal SS, Corrigan LL, Bratta J, Kehrer JP. Acrolein causes inhibitor kappaB-independent decreases in nuclear factor kappaB activation in human lung adenocarcinoma (A549) cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9200–9206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reddy S, Finkelstein EI, Wong PS, Phung A, Cross CE, van der Vliet A. Identification of glutathione modifications by cigarette smoke. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33:1490–1498. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Witz G. Biological interactions of alpha,beta-unsaturated aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;7:333–349. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaimes EA, DeMaster EG, Tian RX, Raij L. Stable compounds of cigarette smoke induce endothelial superoxide anion production via NADPH oxidase activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1031–1036. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000127083.88549.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uchida K, Shiraishi M, Naito Y, Torii Y, Nakamura Y, Osawa T. Activation of stress signaling pathways by the end product of lipid peroxidation. 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal is a potential inducer of intracellular peroxide production. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2234–2242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He YY, Huang JL, Ramirez DC, Chignell CF. Role of reduced glutathione efflux in apoptosis of immortalized human keratinocytes induced by UVA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8058–8064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trotter EW, Collinson EJ, Dawes IW, Grant CM. Old yellow enzymes protect against acrolein toxicity in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:4885–4892. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00526-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dick RA, Kwak MK, Sutter TR, Kensler TW. Antioxidative function and substrate specificity of NAD(P)H-dependent alkenal/one oxidoreductase. A new role for leukotriene B4 12-hydroxydehydrogenase/15-oxoprostaglandin 13-reductase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40803–40810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105487200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]