Abstract

Introduction

In the past decade, the use of the Internet as a forum for communication has exponentially increased, and research indicates that excessive use is associated with psychiatric symptoms. The present study examined the rate of Internet use in adolescents with personality disorders, with a focus on schizotypal personality disorder (SPD), which is characterized by marked interpersonal deficits. Because the Internet provides an easily accessible forum for anonymous social interaction and constitutes an environment where communication is less likely to be hampered by interpersonal deficits, it was hypothesized that SPD youth will spend significantly more time engaging in social activities on the Internet than controls.

Methods

Self-reports of daily Internet use in adolescents with SPD (n = 19), a control group with other personality disorders (n = 22) and a non-psychiatric control group (n = 28) were collected.

Results

Analyses revealed that the SPD participants reported significantly less social interaction with ‘real-life’ friends, but used the Internet for social interaction significantly more frequently than controls. Chat room participation, cooperative internet gaming, and to a lesser degree, email use, were positively correlated with ratings of SPD symptom severity and Beck Depression Inventory scores.

Discussion

Findings are discussed in light of the potential benefits and risks associated with Internet use by socially isolated SPD youth.

Keywords: Schizotypal, Adolescent, Internet, Social Deficit

1. Introduction

Internet use is a rapidly growing technological and social phenomenon that has increased from 26.2% of U.S. homes having access in 1998 to 41.5% in 2000, and roughly 9.6% (581 million users) of the world population uses the Internet (NTIA Release, 2000). There is an expanding body of literature indicating that Internet use is linked with psychiatric symptoms and syndromes. Numerous case reports document that some heavy Internet users (i.e., individuals using the Internet for more than several hours per day for non-work related activity) suffer from psychiatric disorders (Treuer, et al., 2001; Sa’adiah, 2002; Iftene & Roberts, 2004). Similarly studies of young adult samples indicate that self-reported loneliness is positively correlated with the rate of Internet use (Engelberg & Sjoberg, 2004; Nichols & Nicki, 2005), and individuals who report excessive Internet use are characterized by an elevated rate of psychiatric disorders (Blacket al., 1999; Shapira, et al., 2001; Shapira et al., 2003; Yoo et al., 2004). A recent study of normal high school students revealed that heavy Internet use was associated with heightened psychiatric symptoms on self report measures (Yang et al., 2005).

Some mental health experts have expressed concern that excessive Internet use may have a negative impact and contribute to psychiatric symptoms (Bremer, 2005). For example, Shapira and colleagues (2003) argue that heavy Internet use may negatively impact social and emotional functioning. As a reflection of these concerns, it has been suggested that heavy Internet use should be considered a disorder in its own right; and researchers have variously labeled it “Internet addiction disorder”, “Internetomania”, and “pathological Internet use” (Orzack, 1999).

In contrast, it has been suggested by some researchers that for many individuals the Internet can serve as a resource for social support that is unavailable elsewhere (Berger, et al., 2005). For example, Wolak and colleagues (2003) conducted a telephone survey to explore the characteristics of youth who had formed close relationships via the Internet. They found that youth who had on-line relationships were more likely to report depression, sexual assault, and conflict or poor communication with parents. Thus, troubled youth may use the Internet as a venue for social involvement. Of course, the findings linking high rates of Internet use with adjustment problems may simply indicate that individuals with such problems are drawn to the Internet. In other words, high rates of Internet use may reflect a dysfunctional tendency to avoid direct social interaction.

Because Internet use is a relatively new and burgeoning phenomenon, systematic research aimed at characterizing problematic Internet use and understanding its relation with psychiatric disorders is in its infancy (Goldsmith and Shapira, 2006). In particular, there is a dearth of empirical studies of the psychiatric correlates of Internet use by adolescents, and we are aware of no studies of Internet use in clinical samples of youth. Yet, researchers and clinicians recognize that the Internet is rapidly growing, and that excessive Internet use appears to be linked with psychiatric symptoms and may be detrimental. For these reasons, there is a need for systematic research aimed at identifying the nature and correlates of Internet use by youth with adjustment problems.

Schizotypal personality disorder (SPD) involves a variety of social and cognitive deficits that are viewed as subclinical manifestations of schizophrenia. It can be reliably diagnosed in adolescents, and is a risk factor for later psychotic disorder (Tyrka et al., 1995; Walker et al., 1998). The diagnostic criteria for SPD include excessive social anxiety, odd speech, constricted affect, suspiciousness/paranoia, ideas of reference, odd beliefs/magical thinking, and unusual perceptual experiences (DSM-IV, 2004). A key criterion for SPD is a “lack of close friends or confidants other than first-degree relatives” (Criterion 7, APA, 2000).

The symptoms of SPD interfere with social interaction (Ambelas, 1992). During adolescence, a time period characterized by an increasing degree of peer evaluation or scrutiny, odd or eccentric behavior will likely hamper peer relations (Wolf, 1991). For example, the inappropriate or constricted affect (Criterion 6) associated with SPD impairs communicative ability (Dworkin et al., 1993). Further, researchers have found that, compared to psychiatric and non psychiatric controls, adolescents with SPD exhibit marked nonverbal deficits including irregular and limited gesturing (Mittal et al,, 2006), higher frequencies of motor abnormalities, (Walker et al., 1999; Mittal et al., in press), and problems in interpreting non-verbal cues (Logan, 1999).

Given these findings, it is plausible that individuals with SPD would be drawn to the Internet because it is a venue in which receptive and expressive interpersonal deficits are less likely to reciprocate in exclusionary behavior from peers. Specific symptoms of SPD might be associated with specific patterns of internet use. For example, a proclivity toward magical thinking or an over-active fantasy life (Criterion 2) might be associated with a preference to use fantasy games on the internet as a platform for interacting with peers. Further, it is possible that cognitive stores that would have been used while compensating for interpersonal and social deficits during real-world social interactions (Logan, 1999), may be freed up while interacting in a virtual environment; because this could potentially result in an enhancement of performance in interactive goal driven tasks, it is possible that individuals with SPD might prefer this sort of game. Another point to consider is that odd speech (Criterion 4) and inappropriate or constricted affect (Criterion 6) may lead to peer-rejection during real-life encounters. However, those individuals with SPD who yearn for interaction with peers might find chat-rooms to be an outlet where these symptoms are less likely to interfere. Finally, there are some symptoms that are likely to relate to social internet use across domains. More specifically, excessive social anxiety (Criterion 9) may lead schizotypal individuals to choose gaming, emailing, and chatting as a social platform. Factors potentially contributing to social anxiety, such as misinterpreting interpersonal situations, and fear of negative peer appraisal, would be limited in this environment. Furthermore, it would also be considerably easier to escape from anxiety provoking situations on the internet.

The present study tests the hypothesis that, compared to control groups, individuals with SPD would report spending more time on the Internet, including both chartrooms and online games. Also, based on past research findings, it was predicted that greater Internet use would be associated with more severe SPD symptoms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants in the present research are a subgroup of adolescents who participated in an IRB approved study of adolescent development and risk for psychotic disorders being conducted at Emory University. Informed consent was obtained from parents as well as participants (details of the studies are described in Mittal et al, 2006). Participants between the ages of 12 and 18 were recruited from the Atlanta area through newspaper announcements directed at parents describing SPD symptoms in lay terminology. Participants for the non-clinical comparison group (i.e., normal controls - NC) were recruited through a community based participant pool.

All participants who had access to a computer and completed our survey on Internet use were included in this report. The resultant sample (N = 69) consisted of 19 adolescents who met criteria for SPD, 22 with other Axis II disorders (OPD), and 28 with no DSM-IV disorder (NC). Diagnoses are presented in Table 1. All resided at home and attended school. Consistent with previous reports, the rate of comorbid personality disorder was high, at (50%), thus the number of diagnoses exceeds the number of participants. Exclusion criteria were major medical illness, neurological disorder, mental retardation, or Axis I disorders. Participants were administered a partial battery of subtests from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Test, Third Edition (WAIS-III) (Donders, 1997). For the present study, adolescents who reported no regular access to a computer (N = 3; 1 SPD, 2 NC) were excluded). See Table 2 for a description of the sample characteristics

Table 1.

DSM-IV Diagnoses in SPD and OPD Control Group

| Axis II Diagnosis | SPD (n = 19) | OPD (n = 22) |

|---|---|---|

| Schizoid PD | 31.5% | 4.5% |

| Schizotypal PD | 100.0% | 0.0% |

| Paranoid PD | 15.7% | 4.5% |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 0.0% | 36.3% |

| Borderline PD | 5.2% | 13.6% |

| Histrionic PD | 0.0% | 4.5% |

| Narcissistic PD | 10.5% | 13.6% |

| Avoidant PD | 10.5% | 22.7% |

| Obsessive Compulsive PD | 5.2% | 13.6% |

Note: Individuals in the NPD group did not meet criteria for any personality disorder; The number of disorders exceeds the total group n because of comorbidity

Table 2.

Characteristics of Current Sample (n = 69)

| 1 No Disorder (n = 28) | 2 Schizotypal (n = 19) | 3 Other Disorder (n = 22) | Grand Total (n = 69) | Group Diff. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Males | 50.0% | 57.8% | 40.9% | 49.2% | NS |

| Females | 50.0% | 42.1% | 59.0% | 50.7% | NS |

| Age (yrs.) | |||||

| M | 14.07 | 14.53 | 14.55 | 14.38 | |

| (SD) | (1.94) | (1.87) | (1.71) | (1.84) | NS |

| Intelligence Quotient (I.Q.)a | |||||

| M | 104 | 98 | 101 | 101 | |

| (SD) | (16.17) | (20.23) | (18.54) | (18.06) | NS |

Intelligence Quotient is derived from Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children - Third Edition (WISC-III)

2.2 Diagnostic Process

DSM IV diagnoses were determined through administration of structured clinical interviews. The assessment of personality disorders during the adolescent period has been shown to be valid (Johnson, Brent, Connolly, Bridge, et al., 1995) and broadly reliable (Bernstein et al., 1993). Furthermore, the SIDP-IV, the assessment tool used in the present study, has been shown to have good inter-rater reliability (Brent et al., 1990). In addition to the SCID-II, or the SIDP-IV, the SCID Psychotic Screen (Spitzer et al., 1990) was administered to rule out Axis I psychotic or mood disorder. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, 1987) was also used to screen for mood disorders. To determine the number of real-life friendships for participating adolescents we used information from an item from the noted structured interview (SIDP-IV; Close Relationships: item #2: close friends or confidants other than first-degree relatives).

Interviews were administered by trained graduate-level examiners. Diagnoses were made by consensus of project staff, including an experienced child and adolescent psychiatrist, after reviewing the videotaped interviews, medical histories, parent reports, and other materials. Inter-rater reliability for symptom dimension ratings were high, ranging from r =.80 to r =.94.

2.3 Procedures

Participating adolescents completed a brief survey designed to assess the amount of time spent in various activities on the Internet. The participants were given oral instructions, “‘We are interested in the time you spend participating in social activities while using the internet.’ ‘As you are completing the questions on this survey, please remember, we are interested in learning about the number of minutes you spend on the internet participating in activities that involve communicating with other people.’” The survey contained the following questions; “How many minutes a day do you spend on the Internet”, “How many minutes a day do you spend e-mailing on the Internet?”, “How many minutes a day do you spend in chat rooms?”, “How many minutes a day do you spend playing interactive on-line games?”. Responses were given on a 9-point scale (0 representing no time and the highest score of 9 representing “more than 4.5 hours”.

3. Results

One-way Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to test for demographic differences among the diagnostic groups. There were no significant group differences in mean age of participant, or mean years of parental education across the three groups. In addition, results indicated no significant differences in intelligence tests scores (WISC-III, Donders 1997). Chi Square tests revealed no significant group differences in sex. Furthermore, there were no significant correlations between intelligence and daily time spent emailing, chatting on-line, or playing Internet games.

One-way ANOVAs were conducted to compare the diagnostic groups on interpersonal relationships (this information was taken from SIDP-IV, Close Relationships: item #2, “lacks close friends or confidants other than first-degree relatives”). As expected there was a significant difference between groups for number of interpersonal ‘real-life’ friendships, F(2, 67) =9.49, p < .01, (eta squared = .22). Post hoc tests indicated that NC and OPD groups were not significantly different and that both groups showed higher mean frequency of friendships than the SPD group, p < .05.

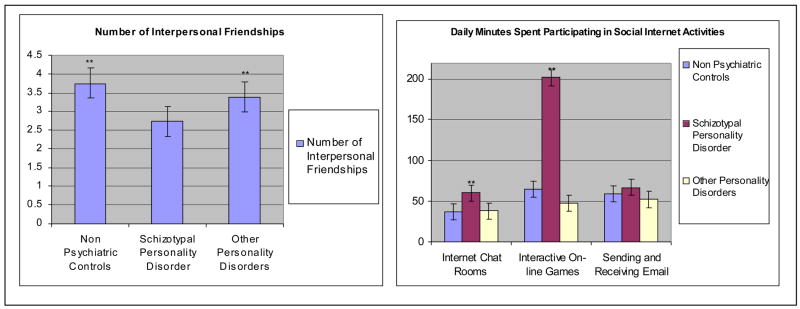

ANOVAs were also conducted on the data from the Internet survey. (See Table 3 for descriptive statistics and a summary of the analyses). To facilitate interpretation, the likert scale points (each representing a one-half hour increment) were converted to minutes. Consistent with the hypotheses, there was a significant group difference for time spent in chat rooms F(2,67) = 3.93, p < .05, (eta squared = .10) and time spent playing on-line games F(2,67) = 3.04, p < .05. Post hoc testing for both analyses revealed that the SPD group spent significantly greater time than both NC and OPD groups, and that there was no significant difference between the latter two groups. In terms of overall internet use, there was a significant group difference F(2,67) = 3.07, p < .05; post hoc tests indicated that while SPD group spent significantly more time on the internet than OPD but not NC controls and that there were no significant differences between controls. There were no significant diagnostic group differences for time spent writing and receiving emails. (See Figure 1 for an illustration of the group differences). Although the SPD group was slightly elevated on the BDI, there were no significant group differences for this measure.

Table 3.

Group Differences of Internet use, Social Isolation and Depression

| 1 No Disorder (n = 28) | 2 Schizotypal (n = 19) | 3 Other Disorder (n = 22) | Grand Total (n = 69) | Group Diff. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Real-life Friendships | |||||

| M | 3.75 | 2.73 | 3.38 | 3.35 | 2 < 1, 3**; 1 = 3 |

| (SD) | (.58) | (.99) | (.80) | (.87) | |

| Effect Size | Eta2 = .22 | ||||

| Daily Time Spent Writing and Receiving E-maila | |||||

| M | 58.8 | 66.9 | 51.9 | 58.8 | 1 = 2 = 3 |

| (SD) | (49.2) | (44.4) | (57.3) | (50.1) | |

| Effect Size | N.S. | ||||

| Daily Time Spent in Internet Chat Roomsa | |||||

| M | 36.3 | 60.0 | 38.1 | 43.2 | 2 > 1, 3**; 1=3 |

| (SD) | (29.4) | (47.7) | (26.4) | (31.5) | |

| Effect Size | Eta2 = .10 | ||||

| Daily Time Spent in interactive on-line Gamesa | |||||

| M | 64.8 | 202.2 | 47.4 | 66.9 | 2 > 1, 3**; 1=3 |

| (SD) | (60.3) | (82.5) | (45.0) | (65.7) | |

| Effect Size | Eta2 = .10 | ||||

| Daily Time Spent on Interneta | |||||

| M | 116.4 | 145.5 | 119.4 | 119.4 | 2 > 3*; 1=2, 1=3 |

| (SD) | (68.1) | (85.5) | (73.2) | 77.4 | |

| Effect Size | Eta2 = .07 | ||||

| BDI Score | |||||

| M | 9.17 | 14.15 | 11.32 | 11.33 | 1 = 2 = 3 |

| (SD) | (6.89) | (8.23) | (9.02) | 8.11 | |

| Effect Size | N.S. | ||||

Note: p ≤ .01

Daily time is reported in minutes

Figure 1. Schizotypal individuals have significantly fewer interpersonal relationships, but spend significantly more time participating in social Internet activities.

** Schizotypal adolescents reported significantly fewer “real-life” friends, while there were not differences between controls.

Adolescents with SPD reported spending significantly more time than controls participating in internet chat rooms and playing socially interactive on-line games but not sending emails; there were no differences between control groups.

Bivariate correlations were used to test the associations of Internet use with self-reported friendships and BDI score. Because previous studies have shown that increased internet use is associated with depression amongst youngsters (e.g., Wolak et al., 2003), partial correlations, controlling for BDI, were used to test for association of Internet use with SPD symptoms (as assessed by the SIPD-IV; nine symptoms each rated from 0 to 3) and the results are presented in Table 4. The number of ‘real-life’ interpersonal friendships was not associated with time spent emailing, but was significantly negatively correlated with time spent in a chat-room, and showed a strong negative trend for time spent participating in on-line games. Thus adolescents with fewer friendships spend more time in chat-rooms on the Internet. Consistent with the prediction, daily time in chat rooms was positively associated with SPD symptoms and the BDI score, indicating that those who spend more time in chat rooms have more severe symptom ratings. Daily time spent participating in on-line games was associated with three SPD symptoms, and showed a positive trend with elevated BDI scores. Again, more severe ratings of odd/eccentric behavior and unusual perceptual experiences were linked with more time spent in on-line games, whereas inappropriate/constricted affect was not associated with participation in on-line games. Time spent emailing was associated with odd/eccentric behavior and social anxiety.

Table 4.

Associations between Social Internet use and Psychiatric Symptoms (n = 69)

| Psychiatric Symptoms | Chat room | On-line Games | |

|---|---|---|---|

| “Real-Life” Friendshipsa | .02 | −.20* | −.18 |

| Beck Depression Inventoryb | .12 | .39** | .18 |

| Schizotypal Symptomsa | |||

| Ideas of Reference | .07 | .42** | .19 |

| Odd Beliefs/Magical Thinking | −.21 | .02 | −.05 |

| Unusual Perceptual Experience | −.08 | .24* | .26* |

| Odd thinking and Speech | .18 | .12 | .25 |

| Suspicious/Paranoid | .11 | .26* | .15 |

| Inappropriate/Constricted Affect | .02 | .17 | −.13 |

| Odd and/or Eccentric Behavior | .23* | .24* | .29* |

| Lack of Close Friends | .05 | .07 | .06 |

| Excessive Social Anxiety | .24* | .24* | .33** |

p ≥ 0.0;

p ≥ 0.05;

Partial correlations controlling for BDI

Bivariate correlations

4. Discussion

The present study examined the Internet use of adolescents with SPD, other personality disorders, or no disorder. Based on the social deficits observed in SPD, it was hypothesized that adolescents with SPD would spend a greater amount of time using the Internet. The findings generally support this hypothesis, in that the SPD group reported more time spent in chat rooms and playing on-line games. (See Figure 1 for a graphical illustration of the findings). The one exception to this pattern concerned time spent emailing, where there was no significant diagnostic group difference. One plausible explanation for the absence of a diagnostic group difference in time spent e-mailing is that this is an activity that typically involves social contacts with friends. Because the SPD adolescents report having fewer friends, opportunities for e-mailing would be limited. On the internet, individuals with SPD may not be immediately excluded due to abnormal nonverbal behavior as is likely to occur in real-life interactions.

In addition, there were significant relations between symptoms ratings and Internet use. Specifically, time spent in chat rooms and time spent participating in on-line games were both positively correlated with several SPD symptoms and self-reported depression on the BDI. It is of importance to note that the SPD symptom ratings are based on both the individual’s self report and the examiner’s observations. Thus report bias is not likely to account for these relations. Also, as expected, there was a negative correlation between number of ‘real-life’ friends, and time spent chatting on the Internet.

The finding that SPD youth are more inclined than healthy adolescents to engage in social (i.e., chat room) interactions on the Internet suggests that they are socially motivated. Thus, in contrast to those with schizoid personality disorder, who are assumed to be socially isolated because of disinterest or a lack of desire, those with SPD may be motivated to establish social interactions (Mittal, et al., 2007). In this sense, Internet use is not necessarily a negative phenomenon, but rather may provide a social outlet that is otherwise difficult to attain due to interpersonal deficits.

Alternatively, it is possible that the SPD youth tend to use chat rooms to act out socially, rather than to make positive social contacts. Thus, chat room use could be an expression of social hostility, and reflect a lack of motivation to engage in actual social contact. Another unanswered question is whether Internet use is thwarting the child’s motivation to engage in real-life social interactions. It is possible that reducing access would increase real-life social interactions and, perhaps, reduce ratings of symptom severity. Finally, excessive Internet use may put these youth at greater risk for exposure to negative Internet influences or victimization by predators. In order to address these questions, experimental studies that manipulate access to the Internet are needed.

When interpreting the present results it is important to be cautious about inferring motives, intentions or causal mechanisms. Greater Internet use may be a consequence of the symptoms or a contributor to symptoms. Future studies should aim to determine the longitudinal course of Internet use and its covariance with symptomatology. More specifically, it is of interest to determine whether Internet use alters the progression of symptomatology (particularly symptoms relating to depression, isolation, and loneliness). On the other hand, the Internet may have untapped therapeutic potential for at-risk youth. It will, therefore, be important to explore potential therapeutic uses of the Internet, perhaps as a virtual step in social skills training that can be later generalized to real-life interpersonal situations.

There were several limitations in the present study. First, because of a relatively small ‘n’, our ability to draw strong conclusions or interpretations was limited. This also lowered statistical power thus decreasing the ability to detect subtle differences. Second, it is important to note that the internet has continued to evolve, and several very popular trends of use have burgeoned since the completion of data collection. Notably, our study failed to ask questions regarding instant messaging (a very interactive internet activity that is likely to be a good reflection of interpersonal relationships). Future studies examining internet use and adolescents would highly benefit from a more sophisticated measure of internet use with more detailed questions and a revised “up-to-date” subject matter. One potential is using new methodologies utilizing software that actually tracks internet activity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Amanda McMillan and Nancy Bliwise, who donated their time and energy to aiding in conceptual development and statistical analyses. We would also like to thank Noel Alexander for his enthusiastic consultation regarding the nuances of Internet gaming

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript.

Contributors

Author Mittal conducted statistical analyses and the literature search. The author also wrote the first draft of the present manuscript.

Author Tessner aided in the writing of the manuscript and in developing the theoretical conceptualizations.

Author Walker helped to design the study, wrote the protocol, obtained grant funding, directed data collection, and edited the manuscript.

All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NITA) and Economics and Statistics Administration. Falling through the net: Toward digital inclusion (executive summary) [Online NTIA release] 2000 Retrieved 20 November, 2002, in: http:www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/digitaldivide/execsumfttn00.htm.

- Ambelas A. Preschizophrenics: Adding to the evidence, sharpening the focus. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;160:401–404. doi: 10.1192/bjp.160.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Berger M, Wagner TH, Baker LC. Internet use and stigmatized illness. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(8):1821–1827. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DW, Belsare G, Schlosser S. Clinical features, psychiatric comorbidity, and health-related quality of life in persons reporting compulsive computer use behavior. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(12):839–844. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer J. The Internet and Children: Advantages and Disadvantages. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;14(3):405–428. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Zelenak JP, Bukstein O, Brown RV. Reliability and validity of the Structured Interview for personality disorders in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychaitry. 1990;29(3):349–354. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199005000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan SE. A social skill account of problematic Internet use. J Commun. 2005;55(4):721–736. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin RH, Cornblatt BA, Friedmann R, Kaplansky LM, Lewis JA, Rinaldi A, et al. Childhood Precursors of Affective vs. Social Deficits in Adolescents at Risk for Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19(3):563–577. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.3.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelberg E, Sjoberg L. Internet Use, Social Skills, and Adjustment. CyberPsychol Behav. 2004;7(1):41–47. doi: 10.1089/109493104322820101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith TD, Shapira NA. Problematic Internet Use. In: Hollander E, Stein DJ, editors. Clinical Manuel of Impulse Disorders. American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington DC: 2006. pp. 291–308. [Google Scholar]

- Iftene F, Napoca C, Roberts N. Internet Use in Adolescents: Hobby or Avoidance. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49(11):789–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CC, Chen SH, Yen CF. Proposed diagnostic criteria of Internet addiction for adolescents. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(11):728–733. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000185891.13719.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan CB. Emotion Recognition and Schizotypal Personality Disorder. Emory U; Atlanta: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal VA, Tessner KD, McMillan AL, Delawalla Z, Trottman H, Walker E. Gesture Behavior in Unmedicated Schizotypal Adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115(2):351–358. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal VA, Kalus O, Bernstein DP, Siever LJ. Schizoid Personality Disorder. In: O’Donohue WO, Lilienfeld ST, Fowler KA, editors. Handbook of Personality Disorders: Towards the DSM V. Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal VA, Dhruv S, Tessner KD, Walder DJ, Walker EF. The relations among putative bio risk markers in schizotypal adolescents: minor physical anomalies, movement abnormalities and salivary cortisol. Biol Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.043. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols LA, Nicki R. Development of a Psychometrically Sound Internet Addiction Scale: A Preliminary Step. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18(4):381–384. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orzack MH, Orzack DS. Treatment of computer addicts with complex co-morbid psychiatric disorders. CyberPsychol Behav. 1999;2(5):465–473. doi: 10.1089/cpb.1999.2.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sa’adiah R. The Internet as a means for promoting the recovery and empowerment of people with mental health problems. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2002;39(3):192–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Vander Bilt J. “Computer addiction”: a critical consideration. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(2):162–168. doi: 10.1037/h0087741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira NA, Goldsmith TD, Keck PE, Jr, Khosla UM, McElroy SL. Psychiatric features of individuals with problematic Internet use. J Affect Disor. 2000;57(1–3):267–272. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00107-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira NA, Lessig MC, Goldsmith TD, Szabo ST, Lazoritz M, Gold MS, et al. Problematic Internet use: Proposed classification and diagnostic criteria. Depress Anxiety. 2003;17(4):207–216. doi: 10.1002/da.10094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treuer T, Fabian Z, Furedi J. Internet addiction associated with features of impulse control disorder: Is it a real psychiatric disorder? J Affect Disord. 2001;66(2–3):283. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Cannon TD, Haslam N, Mednick SA. The latent structure of schizotypy: I: Premorbid indicators of a taxon of individuals at risk for schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104:173–183. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker E, Baum K, Diforio D. Developmental changes in the behavioral expression of vulnerability for schizophrenia. In: Lenzenweger M, Dworkin B, editors. Experimental psychopathology and the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. American Psychological Association; Washington DC: 1998. pp. 469–492. [Google Scholar]

- Walker E, Lewis N, Loewy R, Palyo S. Motor dysfunction and risk for schizophrenia. Dev Psychopathology. 1999;11(3):509–523. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolak J, Mitchell KJ, Finkelhor D. Escaping or connecting? Characteristics of youth who form close online relationships. J Adolesc. 2003;26(1):105–119. doi: 10.1016/s0140-1971(02)00114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S. “Schizoid” personality in childhood and adult life. I: The vagaries of diagnostic labeling. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:615–620. doi: 10.1192/bjp.159.5.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CK, Choe BM, Baity M, Lee JH, Cho JS. SCL-90-R and 16PF profiles of senior high school students with excessive Internet use. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(7):407–414. doi: 10.1177/070674370505000704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HJ, Cho SC, Ha J, Yune SK, Kim SJ, Hwang J, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity symptoms and Internet addiction. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;58(5):487–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]