Abstract

Arrays suitable for genotoxicity screening are reported that generate metabolites from cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs) in thin-film spots. Array spots containing DNA, various human cyt P450s, and electrochemiluminescence (ECL) generating metallopolymer [Ru(bpy)2PVP10]2+ were exposed to H2O2 to activate the enzymes. ECL from all spots was visualized simultaneously using a CCD camera. Using benzo[a]pyrene as a test substrate, enzyme activity for producing DNA damage in the arrays was found in the order CYP1B1 > CYP1A2 > CYP1A1 > CYP2E1 > myoglobin, the same as the order of their metabolic activity. Thus, these arrays estimate the relative propensity of different enzymes to produce genotoxic metabolites. This is the first demonstration of ECL arrays for high-throughput in vitro genotoxicity screening.

Bioactivation of xenobiotic molecules by cytochrome P450 (cyt P450, or CYP) enzymes in the human liver is a major source of genotoxicity. Metabolites formed in this way can cause damage to genetic material.1,2 Since levels of cyt P450 enzyme expression vary dramatically in different individuals, subpopulations may be subject to varying degrees of chemical or drug toxicity.3 Thus, knowledge of which isoforms of cyt P450 produce toxic metabolites is critical in the development of new drugs, agricultural chemicals, and other substances that impact the public.

Genotoxic metabolites and their nucleobase adducts can be detected by separation methods such as LC–MS.4,5 These methods are very sensitive and provide specific and detailed molecular information, but may be limited for screening by throughput, analysis time, and cost. On the other hand, alternative, relatively rapid array technologies have been very successful in genomics and proteomics and are in principle capable of many thousands of measurements on a single chip.6

We recently demonstrated rapid, inexpensive, voltammetric genotoxicity screening sensors assembled from films of DNA and cyt P450s in single-electrode7 and eight-electrode formats.8 In a two-step process, test molecules are first bioactivated by the enzymes. Then, possible adducts with DNA nucleobases are detected by voltammetry using ruthenium tris(2,2′-bipyridyl)RuII (Ru(bpy)32+) to catalytically oxidize the guanine bases9 in DNA. Nucleobase adducts formed as a consequence of the enzyme reaction in the enzyme/DNA films are not detected directly, but increases in voltammetric peaks result because the adducts cause DNA to partly unfold, making the guanines more accessible to the catalyst.10 These sensors provided relative rates of DNA damage that showed good correlations to nucleobase adduct formation rates measured by LC–MS and with measures of animal genotoxicity.11 Catalytic poly(vinylpyrinine)–Ru(bpy)22+ polymers can also be incorporated into the DNA/enzyme films, providing sensors with reagentless detection.12

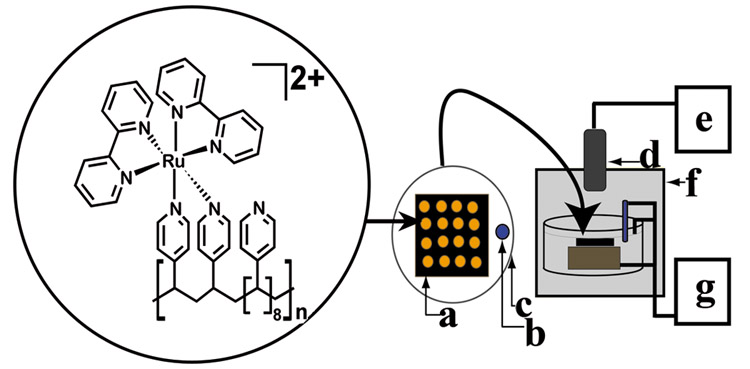

Array technology applied to genotoxicity screening could simultaneously estimate relative rates of DNA damage associated with different enzymes. We reported a prototype eight-unit set of individually addressable electrodes utilizing voltammetry for DNA detection for several of enzymes.8 In this paper, we describe a new approach to genotoxicity screening arrays that employs electrochemiluminescent (ECL) detection. A large electrode block with a single electrical contact was placed into a cell in a dark box with reference and counter electrodes (Scheme 1), eliminating the requirement for individually addressable electrodes. In this device, a pattern of small spots was created on the 2.5-cm2 pyrolytic graphite (PG) electrode block, each containing DNA, a cyt P450 enzyme, and the ECL-generating polymer ruthenium poly(vinylpyridine), [Ru(bpy)2(PVP)10]2+ (RuPVP, Scheme 1). RuPVP generates ECL from DNA by reaction with guanines and provides larger signals from damaged DNA.13 The sensor array emits ECL from each spot upon application of a suitable positive voltage. A CCD camera located above the ECL array14 captures the light emitted from all spots simultaneously. Rates of DNA damage from reactive metabolites produced by individual cyt P450 enzymes can be estimated simultaneously from the dependence of ECL intensity on enzyme reaction time.

Scheme 1. Conceptual Diagram of the ECL Array Instrumentationa.

a RuPVP polymer, DNA, and enzymes are located in each spot on a (a) pyrolytic graphite block; with (b) Ag/AgCl reference electrode, (c) Pt wire counter electrode, (d) CCD camera, (e) computer, (f) gel-doc dark room, and (g) potentiostat for applied voltage control.

[Ru(bpy)2(PVP)10]2+ contains six N-bonds to Ru, and is thought to produce ECL upon reaction with guanines in DNA according to the following pathway:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

ECL generated from adsorbed polymer films is more efficient and intense compared to ECL produced by solution species.15 The RuII center is oxidized by the electrode (eq 1) and subsequently oxidizes a guanine in DNA to form a guanine radical (eq 2). Another RuIII reacts with the guanine radical to form a doubly oxidized guanine (G2ox) and photoexcited RuII* (eq 3) that emits light at 610 nm upon decay back to the ground-state RuII (eq 4). Alternatively, ECL can be generated by interaction from reduced RuI and RuIII to produce the excited RuII* state. We showed previously that ECL detected by a photomultiplier tube from DNA/RuPVP films without enzymes on a single electrode increased with exposure time to styrene oxide,13 which forms guanine adducts.16 ECL emission was directly proportional to the amount of damaged bases on the DNA.

Previous solution-based ECL assays employed target molecules of interest labeled with Ru(bpy)32+.17,18 Upon target binding to a bead, ECL was measured through the use of a sacrificial reductant such as tripropylamine.19 Immobilized Ru(bpy)32+ at single electrodes for the analysis of various biorelated substrates in solution has also been reported, where ECL was detected again via sacrificial reductant.20,21 Direct detection of proline peptides from enzyme hydrolysis without the use of additional reductant was also reported.22 However, none of these reports describes ECL arrays. Further, in our arrays, the sacrificial reductant is the desired measurable target, i.e., the damaged DNA. Therefore, no target labeling is necessary.

In the present work, several isoforms of cytochrome P450 were simultaneously tested for their activity toward the procarcinogen benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P). The cyt P450 enzymes used were chosen for various reasons: Cyt P450 1A2 is involved in phase I oxidative metabolism of polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and heterocyclic amines23,24 and is found in high levels in the human liver.1 Cyt P450 2E1 is found in the human liver and extrahepatic tissues such as lung and is involved in the metabolism of small molecules such as nitrosamines.1 Cyt P450 1B1 is an extrahepatic human form involved in metabolism of aromatic hydrocarbons,1 selectively generating carcinogenic metabolites from PAHs. It is inducible in many tissues24–26 and linked to congenital eye defects.27–29 Cyt P450cam, a bacterial enzyme, has well-understood biocatalysis and is a convenient model cyt P450 enzyme.7,8 Myoglobin was used as a low activity control.5,7

B[a]P was chosen as a model procarcinogen because of its well-known complex metabolism that results in a number of known DNA-reactive metabolites.30,31,35 Several toxic metabolites of B[a]P can be formed by oxidative cyt P450 catalysts, including epoxides, diol-epoxides, and quinines,30–34 as well as one-electron oxidized cation radicals,34,35 all of which form adducts with DNA nucleobases.32,34

Herein, we describe arrays that detect ECL from up to 50 distinct enzyme/DNA spots. CCD imaging of ECL in this approach endows the arrays to rapidly generate useful genotoxic information. This is the first report of an ECL array that can screen genotoxicity from bioactivated metabolites with assignment of relative genotoxicity to specific enzymes. The simplicity of this technology should engender applications to a broad range of chemicals and enzymes.

Experimental Section

Chemicals and Materials

The bis-substituted metallopolymer [Ru(bpy)2(PVP)10](ClO4)2 (RuPVP) was prepared and characterized following previous methods13,15,36 (see Supporting Information). Calf thymus double-stranded (ds)-DNA (type I) and α-naphthoflavone (αNF) were from Sigma. Myoglobin (Sigma, MW 17 400, horse heart) dissolved in 10 mM pH 5.5 sodium acetate buffer was filtered through an Amicon YM30 membrane (MW 30 000 cutoff). Cytochrome P450 enzymes 101 (cam, MW 46 500),37 1A2 (MW 52 000),38 2E1 (MW 52 000),39 and 1B1 (MW 52 000)40 were expressed from DH5α Escherichia coli containing the proper cDNA and were isolated and purified according to the referenced procedures. Benzo[a]pyrene and BPDE were obtained from the NCI chemical carcinogen reference standard repository (Midwest Research Institute, Kansas City, MO). Water was purified with a Hydro Nanopure system to a specific resistance of >16 MΩ. All other chemicals were reagent grade.

Film Assembly

For ECL arrays, a conducting basal plane PG block (Advanced Ceramics, 2.5 cm2 × 1 cm) was attached to a copper plate connector using silver epoxy and insulated using ethyl acrylate polymer so that only the upper face of the electrode was conducting. The PG block was first polished on 600-grit SiC paper (Buehler) and sonicated in water for 1 min, followed by rinsing with water, then absolute ethanol, and then drying under a stream of nitrogen. The location of enzyme/DNA spots was demarcated by lightly scoring the electrode with a small steel rod in desired locations. Films were deposited following previously established general protocols7,8,10–13,49–51 with modifications that were found to produce distinct, approximately uniform spots on the PG surface and strong ECL signals.

The 2-μL drops of DNA (2 mg mL−1, 10 mM Tris pH 7.1 + 50 mM NaCl) were applied by micropipette at demarcated locations. After 15 min, spots were rinsed with pure water and dried briefly with a stream of nitrogen.

The 1-μL RuPVP (1 mg mL−1, 88% H2O, 12% ethanol) drops were then applied at the same locations in the dark for 15 min followed by rinsing with water and drying with nitrogen.

The DNA/RuPVP sequence was repeated to provide two bilayers of DNA/RuPVP in each spot.

After the second RuPVP application, DNA was applied again, allowed to adsorb for 15 min, rinsed with pure water, and dried with nitrogen. At this juncture, 150 μL of RuPVP (1 mg mL−1, 50% H2O, 50% ethanol) was applied over the entire surface (i.e., not just in the spot locations) for the third and fourth bilayer applications, which was found to enhance ECL signals.

After the fourth bilayer, DNA was applied again for 15 min followed by two enzyme and DNA layers. The 1-μL enzyme applications were applied from solutions of the following concentrations: myoglobin (3 mg mL−1, 10 mM pH 5.5 acetate buffer), cyt P450cam (1 mg mL−1, 10 mM pH 5.5 buffer), and cyt P450 1A2, 1B1, and 2E1 (1 mg mL−1, 50 mM pH 7.4 phosphate buffer). Buffer pH values were chosen to optimize the positive charge on the enzymes based on pI values (cam = 4.6;41 myoglobin (Mb) = 6.9;51 human cyt P450s ∼8, determined by isoelectric focusing experiments (data not shown)) and to ensure stability of the cyt P450 enzymes. Based on previous studies of steady-state adsorption times,42 cyt P450s were adsorbed at 4 °C for 30 min to 1 h, while myoglobin was adsorbed at room temperature for 15 min followed by rinsing with water.

The final spots are denoted in order of layer fabrication as follows: (DNA/RuPVP)4/(DNA/enzyme)2(DNA). After the last DNA layer was rinsed, the electrode was allowed to stand protected from light at 4 °C for at least 12 h. For brevity, the films are referred to as RuPVP/DNA/enzyme films throughout the paper.

Array Measurements

The spotted array was placed in a 150-mL beaker filled to 60 mL with 10 mM acetate buffer + 0.15 M NaCl, pH 5.5. The counter electrode was a platinum wire ring placed directly above the array electrode with an Ag/AgCl reference electrode placed to its right. The beaker was placed in the desired position of the gel documentation dark box. A potential of 1.25 V versus Ag/AgCl was applied to the array electrode for 20 s using a CH Instruments (Austin, TX) model 1232 electrochemical analyzer with ECL acquisition by the CCD camera on the “high sensitivity” setting. Data analysis and quantification was done using GeneSnap and GeneTools software provided by SynGene.

Reactions with Damaging Agent

Safety note: Benzo[a]pyrene and its metabolites are known carcinogens. All manipulations were done under a closed hood while wearing gloves. Incubations of arrays were done by placing a 1.5-μL drop containing 0.5 mM H2O2 + 100 μM B[a]P in 10 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 5.5 + 0.15 M NaCl directly on the RuPVP/DNA/enzyme spots. The reaction was stopped with a 1-min water rinse.

Capillary Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectroscopy (CapLC–MS/MS)

See Supporting Information for a full description of procedures. Briefly, B[a]P metabolites oxidized with Mb were detected from films consisting of only Mb and inert polyions of poly(diallyldimethylamine) (PDDA) and poly(styrene sulfonate) (PSS). Films of architecture PDDA/(PSS/Mb)2 were immobilized on fused-silica microspheres and exposed to 0.5 mM H2O2 and 100 μM B[a]P for 10 min. The reaction solution was extracted with ethyl acetate, evaporated with N2, and reconstituted in 200 μL of methanol. For B[a]P–DNA adduct determination, carbon cloth films containing DNA in place of PSS and Mb were used following the same procedures outlined above.43

Cyt P450cam Film Spectroscopy

See Supporting Information for full details. Briefly, poly(acrylic acid) was amidized onto aminoalkylsilane-treated glass slides, after which layers of PDDA, PSS, and cyt P450cam were adsorbed as described above. The glass slide was wetted with 50 mM phosphate buffer pH 7, and absorbance spectra were obtained with a Hewlett-Packard 8453 UV–visible diode array spectrometer.

Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM)

Assembly was monitored at each step with a QCM (USI Japan) by making films on 9-MHz QCM gold-coated resonators (AT-cut, International Crystal Mfg., Oklahoma City, OK) as described elsewhere.10,51 Briefly, resonators were treated with 3-mercaptopropanoic acid before applying layers as for arrays. Adsorbed mass/area (M/A) of each layer for dried films was obtained from the frequency change (ΔF) using the Sauerbrey equation:7,42

| (5) |

Nominal thickness (d) was estimated using an expression confirmed by high-resolution electron microscopy:44

| (6) |

Results

System Characterization

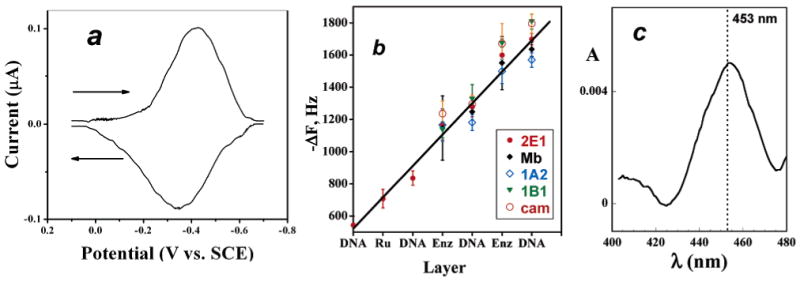

Cyclic voltammograms (CVs) demonstrated that the iron heme enzymes in the films are electrochemically active and give reversible FeIII/FeII peaks (Figure 1a). QCM plots of −ΔF versus layer number (Figure 1b) showed good linearity for all enzymes consistent with a regular and reproducible increase in mass with each added layer.7,8,10 Slow-scan CVs and QCM were used to estimate the amount of enzyme in each spot as well as nominal film thicknesses.

Figure 1.

Characterization data for films: (a) Background-subtracted, smoothed reversible CV of cyt P450 1B1 on PG electrode at 50 mV/s in pH 7.1 phosphate buffer + 50 mM NaCl. Film composition on electrode was PDDA/DNA/cyt P450 1B1/DNA. (b) Influence of film layers added on QCM frequency decrease for enzymes used in this study. The first three film layers are omitted (RuPVP/DNA/RuPVP) for clarity. (c) Visible difference spectrum for immobilized PDDA/cyt P450cam film on glass microscope slide after reduction to the ferrous form and addition of CO showing the characteristic cyt P450 FeII-CO band near 450 nm.

ΔF values and CV reduction peak integrations provided the enzyme surface coverage (Γ) values in Table 1. Both methods provided a consistent enzyme surface coverage, but QCM usually gives a slightly higher Γ. This is likely to involve incomplete electrochemical addressing of enzymes in the film in addition to factors that slightly increase the QCM response such as buffer components. Therefore, the average Γ from the two techniques was used in determining relative DNA damage turnover rates as discussed below.

Table 1. Summary of Enzyme Loadingsa and Nominal Film Thicknessesb.

| enzyme | Γc (nmol cm−2) |

Γd (nmol cm−2) |

av Γ

(nmol cm−2) |

film thickness

(nm) b,c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyt P450 1B1 | 0.032 ± 0.003 | 0.020 ± 0.003 | 0.026 | 36.0 |

| Cyt P450 1A2 | 0.033 ± 0.006 | 0.031 ± 0.005 | 0.032 | 30.6 |

| Cyt P450 cam | 0.058 ± 0.010 | 0.048 ± 0.006 | 0.053 | 34.8 |

| Cyt P450 2E1 | 0.034 ± 0.005 | 0.020 ± 0.003 | 0.027 | 33.5 |

| Mb | 0.130 ± 0.005 | 0.090 ± 0.012 | 0.110 | 32.3 |

Cyt P450cam was used for the spectroscopy experiment due to limited expressed amounts of the human enzymes. Figure 1c shows a difference spectrum of cyt P450cam in a film reduced by dithionite and exposed to CO. The band near 450 nm in the spectrum for the P450(FeII–CO) complex (for which these enzymes were named) is consistent with retention of the enzyme's structural integrity in the films. Denaturation would be indicated by a band at 420 nm.45

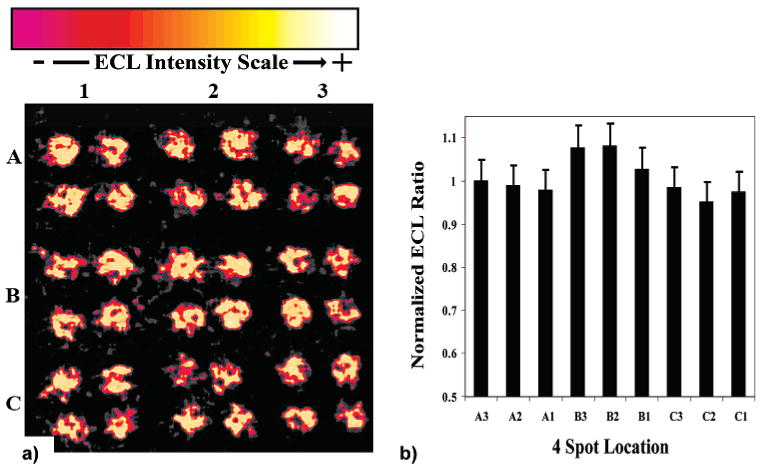

Array Reproducibility

Figure 2 shows a CCD camera image of a typical RuPVP/DNA/enzyme array featuring Mb in each spot upon applying +1.25 V versus Ag/AgCl for 20 s with no exposure to procarcinogens. The bar chart (Figure 2b) shows ECL intensities averaged from four spot units on the array (see Figure 2a for spot locations). Four spot unit averages were used due to slight variances in spot location; i.e., the spot positioning varied slightly from day to day. By referencing the ECL intensity scale in this way, consistent ECL signals are generated from each spot. Figure 2b shows that spot-to-spot intensity on the array varies ±10%, which is reasonable reproducibility. Similar signal variance was found previously for individual sensor electrodes7,8 and is most likely due to variance in film reproducibility for the 36 distinct spots.

Figure 2.

(a) A 36-spot ECL array not exposed to procarcinogenic material showing the spot-to-spot consistency generated from each location on the PG block. Conditions: 10 mM sodium acetate, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 5.5, +1.25 V; 20 s. (b) A column chart showing the relative ECL intensity to spot A3 (upper right corner) from each 4-unit spot location on the PG block.

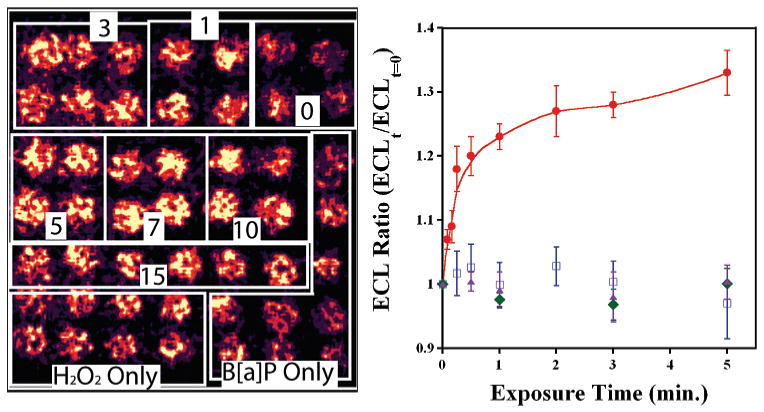

Bioactivation of Benzo[a]pyrene by Cyt P450s

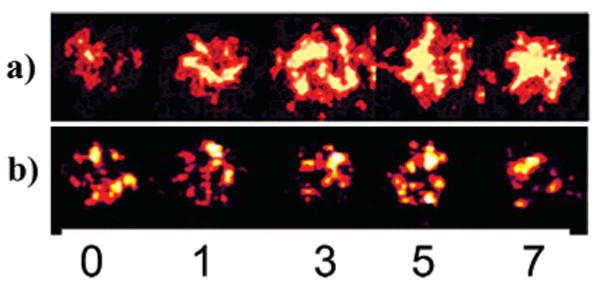

Figure 3 shows a 49-spot array featuring RuPVP/DNA/enzyme spots featuring cyt P450 1B1 exposed to 0.5 mM H2O2 and 100 μM B[a]P for the denoted times. Control spots were exposed to solutions of H2O2 or B[a]P alone. This image demonstrates that an entire set of metabolic reactions and appropriate controls can be evaluated on a single array. Figure 3b shows the ECL ratio plot generated from these experiments, where ECL intensity from a spot exposed to the enzyme reaction is compared to spots at which no enzyme reaction has occurred. Figure 3b features data up to 4 min to highlight the linear region. In this manner, ECL generated from each experiment is compared to an internal standard and data generated from different experiments can be easily compared. The ratio of final/initial ECL response compensates for spot and array variability.

Figure 3.

(a) CCD image of ECL array with 49 individual RuPVP/DNA/enzyme spots containing cyt P450 1B1. Boxes denote spots that were exposed to 0.5 mM H2O2 + 100 μM B[a]P for the labeled times (min). Controls on bottom were exposed to B[a]P or H2O2 only for increasing amounts of time from 1 to 7 min as viewed from right to left (not marked for clarity). (b) ECL ratio plot demonstrating the increase in ECL intensity vs time of enzyme reaction. Controls show ECL response vs time exposed to B[a]P only (blue squares), H2O2 only (green diamonds), and 0.5 mM H2O2 + 100 μM B[a]P + 30 μM of inhibitor αNF (purple triangles).

ECL intensity increased as spots were exposed to longer enzyme reaction times utilizing B[a]P + H2O2. This is seen in Figure 3 by the increase in light intensity over the first minute, followed by a leveling off at 1–7 min. When spots were exposed to either 100 μM B[a]P or 0.5 mM H2O2 alone, there was very little change in ECL signal compared to the spots with no enzyme reaction, which have a ratio of 1 by definition These controls show that H2O2 activates the enzymes but does little damage to DNA and that B[a]P alone does not generate ECL with the inactivated enzyme.

Figure 4 shows a digitally reconstructed picture from a cyt P450 1B1 array exposed to the B[a]P cocktail in the presence and absence of 30 μM αNF, a known strong inhibitor of cyt P450 1A1, 1A2, and 1B1.1,25,26,46–48 The lack of ECL in the presence of the inhibitor suggests that cyt P450 1B1 is metabolizing B[a]P to DNA-reactive species. The ECL ratio plot of spots exposed (α)NF was also shown in Figure 3b.

Figure 4.

Comparison of ECL response of RuPVP/DNA/enzyme spots containing cyt P450 1B1 after denoted exposure time (min) to 0.5 mM H2O2 + 100 μM B[a]P (a) without and (b) with the addition of 30 μM inhibitor αNF.

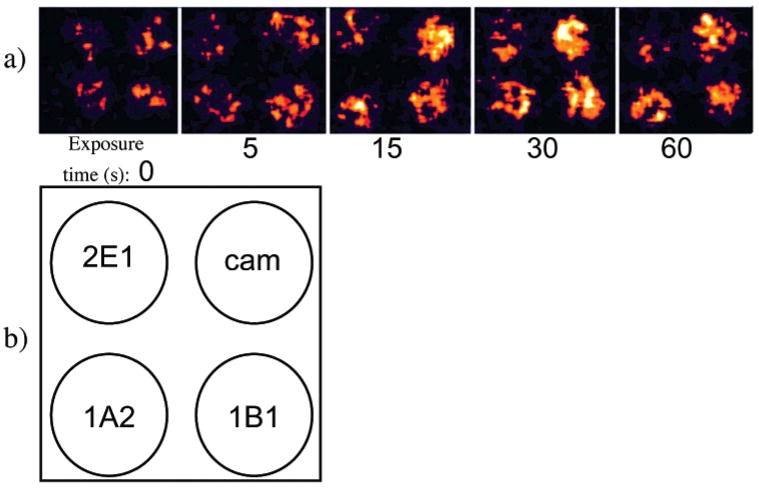

Simultaneous Monitoring of Multiple Enzymes

Figure 5a shows a reconstructed image from an array where four different cyt P450s were immobilized in different spots and reacted for different times. Figure 5b shows the location of the different enzymes within each four-spot unit in the image. As the exposure time to the B[a]P solution increased, ECL from each spot also increased, with different amounts of light intensity from each enzyme film at these short reaction times. Also evident from the image is that the intensity of cyt P450 cam and 1B1 spots increased slightly more than 1A2 over this time period, with very little signal increase seen from the cyt P450 2E1 spots. Figure 6 shows ECL ratios from this array normalized for amount of enzyme found by QCM and CV data (Table 1) from this type of simultaneous monitoring experiment.

Figure 5.

(a) Reconstructed array image where multiple cyt P450 enzymes were present in the Ru/PVP films on a single PG array and exposed to 0.5 mM H2O2 + 100 μM B[a]P for increasing times (s). (b) Schematic showing the location of cyt P450 enzymes in each 4-spot image in Figure 7a.

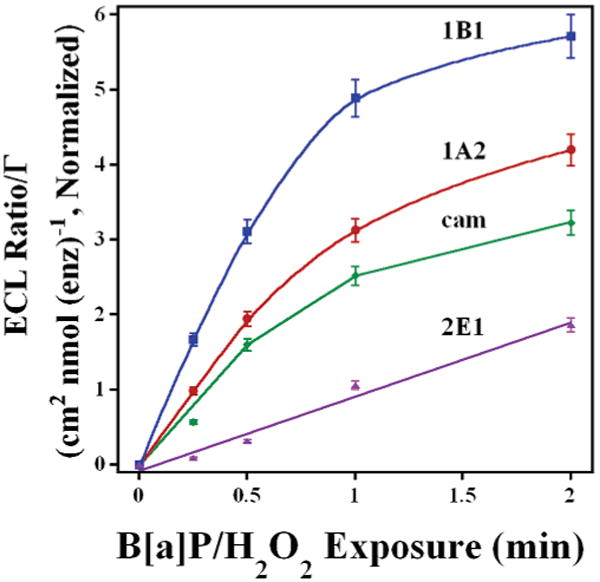

Figure 6.

Influence of B[a]P/H2O2 exposure time for cyt P450 enzymes located on same array. ECL ratio was normalized for amount of enzyme. Cyt P450s used were 1B1(blue), 1A2 (red), cam (green), and 2E1 (purple).

ECL data in Figure 6 can be used to estimate the relative initial enzyme turnover rates resulting in DNA damage. These initial rates reflect B[a]P activation by the different enzymes (Table 2). The rates were obtained by measuring the initial slope of the ECL ratio plots and dividing by the amount of enzyme present in each film.49 These data show that cyt P450 1B1 is the most active enzyme in generating genotoxic B[a]P metabolites, followed by 1A2, cam, 2E1, and finally Mb. Cyt P450 1B1 is ∼2 times more reactive toward B[a]P activation than cyt P450 1A2 and cyt P450cam and ∼4 times more reactive than cyt P450 2E1.

Table 2. Relative Turnover Rates for Enzymes.

| enzyme | init slope

(min−1) |

Γa (pmol) |

rel turnover

(min−1 nmol enzyme−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyt P450 1B1 | 0.340(±0.040) | 3.3 | 100(±14) |

| Cyt P450 1A2 | 0.240(±0.027) | 4.1 | 63(±5.4) |

| Cyt P450 cam | 0.305(±0.025) | 8.0 | 38(±10) |

| Cyt P450 2E1 | 0.090(±0.030) | 3.5 | 26(±7.0) |

| Mb | 0.140(±0.020) | 14 | 10(±2.0) |

For 2 enzyme layers (Table 1) and 0.064 cm2 average spot area.

Array images were also acquired to bioactivate B[a]P in single enzyme arrays. Examples are shown in Figure S1 (Supporting Information). As in Figure 6, the ECL ratio increased with time for each enzyme, as seen in ECL ratio plots (Figure S2 Supporting Information). Higher slopes of the cyt P450s 1B1, cam, and 1A2 at early reaction times again demonstrated that these enzymes are more active in producing genotoxic B[a]P metabolites compared to cyt P450 2E1 and Mb. Similar controls were performed on each array, with similar ECL ratio responses (Figure S3 Supporting Information).

Voltammetric Detection

Square wave voltammograms (SWVs) obtained with RuPVP/DNA/cyt P450 1A2 sensors on individual PG electrodes7,8,10,13 are shown in Figure S5a Supporting Information. This figure shows that SWV peak current (ip) increases upon exposure to B[a]P and H2O2. The peak current ratio plot is shown in Figure S5b. This plot is similar to the ECL ratio plot but shows an increase in current with enzyme reaction time. This behavior is typical when DNA is damaged by either direct damaging agents10,13 or by toxic metabolites produced by bioactivation of procarcinogens by enzymes in thin films.7,8 The SWV data were consistent with the ECL signal increases reported for the same enzyme.8

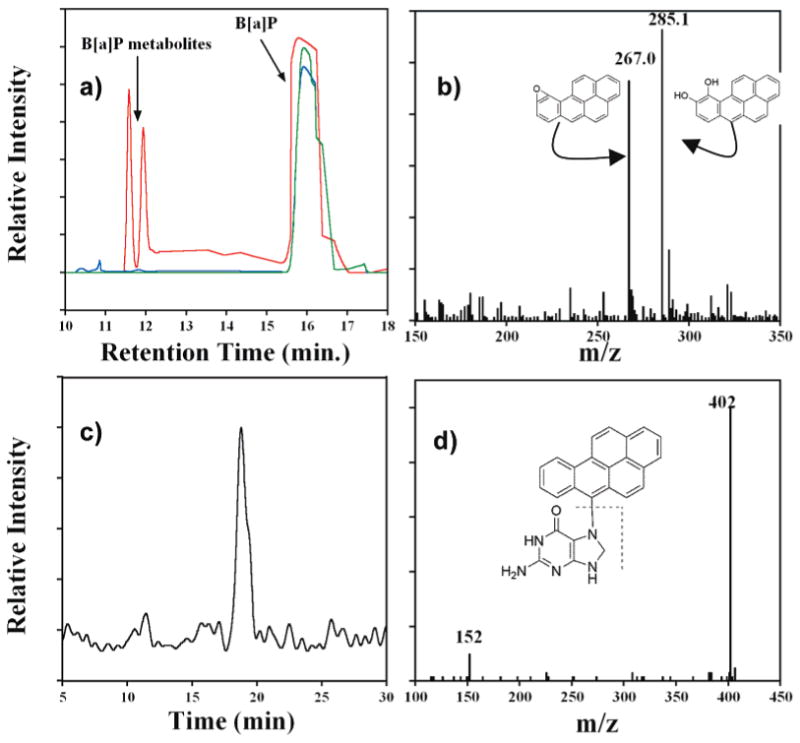

Capillary Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectroscopy

The formation of B[a]P nucleobase adducts and B[a]P metabolites produced in the films was confirmed using CapLC–MS analysis. For metabolite identification, reactions were run with films constructed on hydroxylated 500-nm-diameter fused-silica microspheres. Mb was used for these studies because of its availability in larger quantities, and while cyt P450 generated B[a]P metabolites have been reported,31 little information was available for Mb in this respect. Figure 7a is a CapLC chromatogram showing the elution of the extracted B[a]P reaction mixture after 10-min exposure to a Mb film immobilized showing two groups of eluting peaks. The earlier 11–12-min peaks correspond to products produced from interaction with the myoglobin, while the 17-min peak corresponds to unreacted B[a]P. By comparing to controls, the earlier eluting peaks were identified as oxidized substrate. Figure 7b shows the mass spectrum of the two product peaks from Figure 7a. The mass spectrum confirms the presence of two major [M + H]+ species with m/z 267 and 285. These masses are consistent with epoxidized B[a]P (267) and a gem-diol product (285), presumably via subsequent hydrolysis of the epoxide, which are also shown in Figure 7b.

Figure 7.

(a) CapLC chromatogram showing elution of reaction media after 10-min exposure of Mb immobilized in a thin film on SiO2 microspheres to B[a]P/H2O2 (red). Controls are B[a]P only (blue) and 100 mM B[a]P reacted with 0.5 mM H2O2 for 10 min in the absence of Mb (green). (b) MS for the 11–12-min eluting peaks in (a) along with representative epoxides and diol forms of B[a]P. (c) CapLC chromatogram (select ion mode) measuring total ion current m/z 402 from neutral hydrolysate of DNA/Mb film immobilized on carbon cloth after 10-min exposure to 100 mM B[a]P + 0.5 mM H2O2. (d) MS/MS of the 17-min elution peak in (c) with expected fragmentation pattern of parent B[a]P–guanine ion.

To detect nucleobase adducts, Mb and DNA were immobilized on carbon cloth to better approximate array conditions. These films were exposed to B[a]P/H2O2 for 10 min, and then neutral thermal hydrolysis of the films was done to obtain a sample enriched in N7-guanine adducts.5,11 Figure 7c,d shows a selected ion chromatogram measuring total ion current of m/z 402 [M + H]+ and product ion mass spectrum for the neutral hydrolysate after exposure to the damage solution, respectively. The chromatogram in Figure 7c shows a peak eluting at 17 min with m/z consistent with a one-electron oxidized B[a]P product adducted to guanine.35 Figure 7d shows the MS/MS spectrum from this peak corresponds to a m/z 402 with product ion at m/z 152 [M + H]+, consistent with the predicted fragmentation of a protonated guanine from such an adduct shown in the inset of Figure 7d. Other nucleobase adducts were found as well using this method, mainly that of B[a]P cation radical adducting adenine. The chromatogram and product ion spectrum for this adduct is shown in Supporting Information, Figure S4.

Discussion

Results described above demonstrate that ECL arrays based on RuPVP/DNA/enzyme spots can be used to simultaneously elucidate relative rates of DNA damage from metabolites formed by different cyt P450 enzymes. Figures 3–5 and S1 clearly show that ECL emission in the RuPVP/DNA/enzyme films increases upon exposure to B[a]P and H2O2 denoting the formation of increasing amounts of DNA–B[a]P adducts in the films. No significant increases in ECL occurred for control spots exposed to B[a]P or H2O2 alone (Figures 3b and S5). These results are consistent with peroxide activating the enzymes, which at these low concentrations does not significantly damage DNA.7,8,42,51 After exposure of array spots to H2O2 + B[a]P, the ECL intensity increased presumably due to bulky B[a]P metabolite adducts forming mainly at guanine-rich locations of the DNA located in the films. The distortion of ds-DNA by formation of B[a]P adducts with guanine and other nucleobases has been demonstrated by circular dichroism spectroscopy, NMR, and X-ray crystallography. B[a]P was shown to lie in the minor groove and also intercalate between base pairs.32

Thus, the covalent binding of the B[a]P on the DNA strand perturbs the double helix, allowing closer approach of the ruthenium transition metal center to more rapidly oxidize the damaged guanine base in the ECL detection step (Scheme 2).

The inhibitor control (Figure 4) demonstrates that enzymes in the films are indeed reacting with B[a]P to form reactive metabolites. αNF is a potent cyt P450 inhibitor that binds in the active pocket of the enzyme precluding any oxidation reaction between the heme reaction site and the substrate.1,26,47 No ECL increases were seen in the array when αNF was present, suggesting that reactive B[a]P metabolites are not formed. This behavior is consistent with the report of Shimada et al. in which αNF effectively eliminated cyt P450 1B1 metabolism of B[a]P at concentrations similar to those used in our work.25

Further validation of the enzyme chemistry is provided by LC–MS of B[a]P metabolites and nucleobase–B[a]P adducts under conditions similar to that used for the array (Figure 7). Myoglobin acting as a cyt P450 mimic oxidizes B[a]P to reactive epoxides or cation radicals, similar to horseradish peroxidase.35b Epoxides can hydrolyze under acidic conditions to form the diol product,32 and both epoxide and diol were detected (Figure 7b). B[a]P has been shown previously to be metabolized by various cyt P450 enzymes to numerous reactive metabolites.30,31,34 In vitro studies of these reactions typically involve microsomal or purified enzyme systems consisting of various cyt P450 enzymes with P450 reductase and NADPH to activate the enzymes in the presence of B[a]P to create metabolites, with detection by LC/MS.52,53 B[a]P–nucleobase adducts have also been isolated and detected in this manner.54

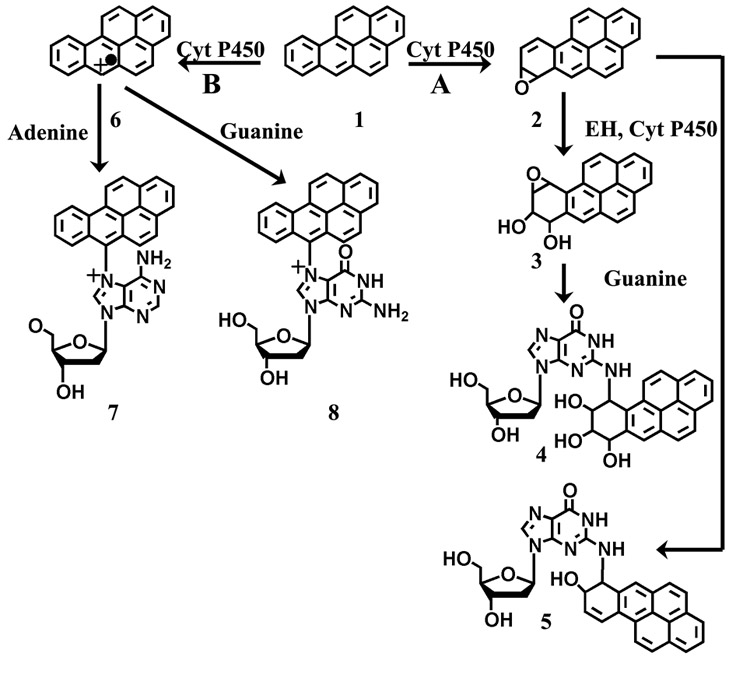

Scheme 3 summarizes B[a]P metabolism by cyt P450s in vivo. Overall, the metabolic route of B[a]P follows two pathways. In pathway A, B[a]P undergoes epoxidation and hydrolysis through interactions with cyt P450s and epoxide hydrolase (EH) eventually emerging as the ultimate carcinogen, 7(R,S)-anti-B[a]P-7,8 dihydrodiol-9,10-expoxide (BPDE). BPDE primarily attacks the N2 position of guanine and forms stable covalent adducts.34 The inclusion of EH is important in rapidly converting the proximate diol product to BPDE.52,55 In the absence of EH, B[a]P metabolites also form DNA adducts, most likely arising from the reaction of B[a]P with cyt P450 to form the proximate epoxide at the 9,10; 7,8; or 4,5 positions and subsequent reaction with the DNA bases, attacking primarily at the same N2 position where BPDE binds.30,31,34,53,58

Scheme 3. Summary of Possible Metabolic Routes for B[a]P in Vivoa.

a Pathway A shows the formation of possible proximal epoxides (1) by cyt P450 followed by direct nucleophilic attack to form guanine adducts at the N2 position (2) or hydrolysis by epoxide hydrolase to form a diol product, and a second cyt P450-mediated epoxidation forming diol epoxides (3), and the final nucleophilic attack forming a guanine adduct at the N2 position (4). Pathway B shows the one-electron oxidation by cyt P450 to form the reactive cation radical (5) with subsequent nucleophilic attack on guanine (6) or adenine (7) forming adducts at the N7 position on the nucleobases.

Also, B[a]P can follow metabolic route B, forming a cation radical from one-electron oxidation, which has been shown to adduct DNA primarily at guanine and adenine N7 and guanine C8.34,35 These adducts cause glycosidic bond instability resulting in DNA abasic sites. Depurinating adducts accounted for over 70% of the detected DNA adducts when mice were treated with B[a]P alone on their skin,34,35 which suggested that the formation of the cation radical is a major route to B[a]P metabolism in vivo. Overall, abasic sites, BPDE adducts, and other B[a]P metabolite adducts have been shown to cause G → T transversions in the replication of the human genome, which can occur on the p53 tumor suppressor gene and ras protooncogene leading to cancer in affected persons.27,56,57

The array format presents a complex reaction environment in which several different B[a]P metabolites react with DNA. Due to the absence of EH in our films and the proximity of DNA to the cyt P450 enzymes and reactive metabolites, one-electron oxidation of the B[a]P by the respective cyt P450 enzymes offers a possible route of DNA damage, especially in light of studies detecting elevated amounts of depurinating B[a]P adducts formed in vivo via this route.35 Adducts detected using CapLC–MS/MS with m/z 402 are consistent with C6 oxidized B[a]P binding at guanine N7 (Figure 7c,d), which is a major adduct formed via this oxidation pathway.34,35 However, due to similarities in m/z, other B[a]P–guanine positional isomers cannot be ruled out. In addition, based on previous reports by our group demonstrating metabolism of styrene to styrene oxide by cyt P450 enzymes and myoglobin,7,8 previous reports of B[a]P epoxides alone adducting DNA,30–32,58 and CapLC–MS validation data presented here, reactions of DNA with B[a]P epoxides along with one-electron oxidized cation radicals cannot be ruled out. Determination of the predominant adducts in the array is a focus of continuing research.

Several studies demonstrated the role of selected cyt P450 enzymes in the metabolism of B[a]P to reactive metabolites. Shimada et al. demonstrated that cyt P450 1B1 was up to 10 times more active than cyt P450 1A1 in converting B[a]P to the 7,8-epoxide.53 In this study, purified cyt P450 1B1 in a recombinant system was shown to be much more active in converting B[a]P to reactive metabolites under these conditions than cyt P450 1A1 and 1A2, while cyt P450 2E1 showed little activity at all in producing reactive metabolites. Kim et al. demonstrated that cyt P450 1A1 was more active toward activating B[a]P to reactive metabolites than either cyt P450 1B1 or 1A2 in a microsomal preparation with EH present in the system.55 In this case, cyt P450 1B1 was shown to be 1.7 times more reactive than cyt P450 1A2 in producing detectable B[a]P metabolites. The differences in kinetic data most likely arise from using purified enzymes reconstituted in lipid mixtures versus microsomal preparations.34,53

Our results show that DNA damage rates are in the order cyt P450 1B1 > cyt P450 1A2 > cyt P450, cyt P450cam, 2E1 > Mb, in good agreement with published reports of enzyme activities. Considering the human cyt P450s (1B1, 1A2, and 2E1), our results are in excellent agreement with reports that showed55 that cyt P450 1B1 produces toxic B[a]P metabolites using purified enzymes and microsomal preparations at ∼2–10 times the rate of cyt P450 1A2. Cyt P450 2E1 produced very few reactive metabolites. In addition, relative enzyme kinetics for cyt P450 cam and 1A2 based on the DNA damage end point found here agree well with those previously obtained using voltammetric sensors.8

The key experimental result presented here is that relative enzyme turnover rates for different enzymes on a toxic substrate can be determined in a very short time using an experimentally simple ECL array format. These arrays can rapidly provide information about which specific enzymes are involved in the bioactivation of procarcinogenics.59 Using B[a]P as a test compound, cyt P450 1B1 emerged as a key cyt P450 isoform in the metabolism, consistent with previous literature reports.53,55,59

The activity of cyt P450 1B1 toward B[a]P metabolism compared to the other enzymes studied is consistent with literature reports discussing in vivo metabolism in that cyt P450 1B1 is an inducible extrahepatic form of cyt P450 located in tissues exposed to PAH compounds or fatty tissues into which such hydrophobic molecules partition, such as the lung and breast.24,25,60,61 Cyt P450 1A2, although capable of metabolizing PAHs into cancer-causing products, is located primarily in the liver and has been shown to be less inducible through exposure to PAHs than cyt P450 1B1.24 Cyt P450 2E1 predominately bioactivates smaller molecular weight, water-soluble cancer suspects such as nitrosamines.1,61 The slightly higher reactivity of B[a]P with cyt P450 1A2 and 2E1 compared to what has been reported previously might be attributable to our experimental conditions as the film environments offer highly concentrated DNA reaction sites versus solution studies and have also been shown to enhance the stability of these proteins.51

In summary, we have presented and validated a novel ECL array format suitable for genotoxicity screening of compounds metabolized by cyt P450 and other enzymes, which also can assign relative genotoxic activity to specific enzymes. The combination of CCD camera, dark box, and traditional electrochemical instrumentation allows for simple, reliable, and robust high-throughput screening. These ECL arrays have a significant advantage over voltammetric arrays in that individual electrical connections to the spots are not necessary. Voltage applied to the entire array excites ECL from all the spots simultaneously, and a large amount of data is obtained rapidly. We are currently extending these arrays to a wider range of procarcinogenic materials, larger numbers of enzymes, and complex phase II metabolic processes.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information Available: Detailed experimental methodology, and 5 additional figures showing digitally reconstructed ECL array data for all cyt P450 enzyme films, ECL ratio plots for all single enzyme arrays, control ECL ratio plots, voltammetric data, and peak ratio plots for cyt P450 1A2, and MS data confirming formation of B[a]P-N7 adenine adduct. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. PHS grant ES03154 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), NIH, USA. The authors thank David Osier for the construction of the copper PG block support.

References

- 1.Schenkman JB, Greim H, editors. Cytochrome P450. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortiz de Montellano PR, editor. Cytochrome P450. Kluwer/Plenum; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Guengerich FP. Asia Pac J Pharmacol. 1990;5:327–345. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gonzalez FJ. Trends Pharm Sci. 1992;13:346–352. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90107-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Guengerich FP. Toxicol Lett. 1994;70:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(94)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Guengerich FP. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:611–650. doi: 10.1021/tx0002583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Guengerich FP, Parikh A, Turesky RJ, Josephry PD. Mutat Res. 1999;428:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Guengerich FP. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001;14:611–650. doi: 10.1021/tx0002583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Cadet J, Weinfeld M. Anal Chem. 1993;65:675A–682A. doi: 10.1021/ac00063a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Koc H, Swenberg JA. J Chromatogr B. 2002;778:323–343. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Farmer PB, Brown K, Tompkins E, Emms VL, Jones DJL, Singh R, Phillips DH. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;207:S293–S301. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarun M, Rusling JF. Crit Rev Eukaryotic Gene Expression. 2005;15:295–315. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v15.i4.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Bensmail H, Haoudi A. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2003;4:217–230. doi: 10.1155/S1110724303209207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hood E. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:A817–A825. doi: 10.1289/ehp.111-a692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Weston AD, Hood L. J Proteome Res. 2004;3:179–196. doi: 10.1021/pr0499693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wagner PD, Verma M, Srivastava S. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1022:9–16. doi: 10.1196/annals.1318.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou L, Yang J, Estavillo C, Stuart JD, Schenkman JB, Rusling JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:1431–1436. doi: 10.1021/ja0290274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang B, Jansson I, Schenkman JB, Rusling JF. Anal Chem. 2005;77:1361–1367. doi: 10.1021/ac0485536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Johnston DH, Glasgow KC, Thorp HH. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;177:8933–8938. [Google Scholar]; (b) Armistead PM, Thorp HH. Anal Chem. 2001;73:558–564. doi: 10.1021/ac001286t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Napier BT, Thorp HH. Langmuir. 1997;13:6342–6344. [Google Scholar]; (d) Ontko AC, Armistead PM, Kircus SR, Thorp HH. Inorg Chem. 1999;38:1842–1846. doi: 10.1021/ic981211w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou L, Rusling JF. Anal Chem. 2001;73:4780–4786. doi: 10.1021/ac0105639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Tarun M, Rusling JF. Anal Chem. 2005;77:2056–2062. doi: 10.1021/ac048283r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yang J, Wang B, Rusling JF. Molec Biosyst. 2005;1:251–259. doi: 10.1039/b506111c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rusling JF, Hvastkovs EG, Schenkman JB. Curr Opin Drug Discovery Dev. In press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Mugweru A, Rusling JF. Anal Chem. 2002;74:4044–4049. doi: 10.1021/ac020221i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mugweru A, Yang J, Rusling JF. Electroanalysis. 2004;16:1132–1138. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mugweru A, Wang B, Rusling JF. Anal Chem. 2004;76:5557–5563. doi: 10.1021/ac049375j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dennany L, Forster RJ, Rusling JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5213–5218. doi: 10.1021/ja0296529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szunerits S, Tam JM, Thouin L, Amatore C, Walt DR. Anal Chem. 2003;75:4382–4388. doi: 10.1021/ac034370s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dennany L, Hogan CF, Keyes TE, Forster RJ. Anal Chem. 2006;78:1412–1417. doi: 10.1021/ac0513919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koskinen M, Vodicka P, Hemminki K. Chem-Biol Interact. 2000;124:13–27. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(99)00137-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miao W, Bard AJ. Anal Chem. 2004;76:7109–7113. doi: 10.1021/ac048782s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson R, Johansson MK. Chem Commun. 2003:2710–2711. doi: 10.1039/b307550h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miao W, Bard AJ. Anal Chem. 2004;76:5379–5386. doi: 10.1021/ac0495236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michel PE, van der Wal PD, Fiaccabrino GC, de Rooij NF, Koudelka-Hep M. Electroanalysis. 1999;11:1361–1367. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin AF, Nieman TA. Biosens Bioelectron. 1997;12:479–489. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jinshun P, Mitoma Y, Uda T, Hifumi E, Shimizu K, Egashira N. Electroanalysis. 2004;16:1262–1265. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butler MA, Iwasaki M, Guengerich FP, Kadlubar FF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:7696–7700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shimada T, Inoue K, Suzuki Y, Kawai T, Azuma E, Nakajima T, Shindo M, Durose K, Sugie A, Yamagishi Y, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Hashimoto M. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1199–1207. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.7.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimada T, Hayes CL, Yamazaki H, Amin S, Hecht SS, Guengerich FP, Sutter TR. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2979–2984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guengerich FP, Chun Y, Kim D, Gillam EMJ, Shimada T. Mutat Res. 2003;523–524:173–182. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoilov I, Rezaie T, Jansson I, Schenkman JB, Sarfarazi M. Mol Vision. 2004;10:629–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schenkman JB, Choudhary D, Jansson I, Sarfarazi M, Stoilov I. Proc Indian Natl Sci Acad. 2003;B69:917–929. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jansson I, Stoilov I, Sarfarzi M, Schenkman JB. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11:793–801. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conney AH. Cancer Res. 1982;42:4875–4917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelboin HV. Physiol Rev. 1980;60:1107–1166. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1980.60.4.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osbourne MR, Crosby NT, editors. Benzopyrenes. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray AW, Grover PL, Sims P. Chem Biol Interact. 1976;13:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(76)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neilson AH, editor. PAHs and Related Compounds. Springer; Berlin: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Rogan EG, Devanesan PD, RamaKrishna NVS, Higgenbotham S, Padvavathi NS, Chapman K, Cavalieri EL, Jeong H, Jankowiak R, Small GJ. Chem Res Toxicol. 1993;6:356–363. doi: 10.1021/tx00033a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen L, Devenesan PD, Higgenbotham S, Ariese F, Jankowiak R, Small GJ, Rogan EG, Cavalieri EL. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9:897–903. doi: 10.1021/tx960004a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Devenesan PD, Higgenbotham S, Ariese F, Jankowiak R, Suh M, Small GJ, Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996;9:1113–1116. doi: 10.1021/tx9600513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Todorovic R, Ariese F, Devenesan P, Jankowiak R, Small GJ, Rogan EG, Cavalieri EL. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:941–947. doi: 10.1021/tx970003y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forster RJ, Vos Johannes G. Macromolecules. 1990;23:4372–4377. [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Keefe DH, Ebel RE, Petersen JA. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(78)52017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisher CW, Caudle DL, Martin-Wixtrom C, Quattrochi LC, Turkey RH, Waterman MR, Estabrook RW. FASEB J. 1992;6:759–764. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.2.1537466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gillam EMJ, Guo ZY, Guengerich FP. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;312:59–66. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jansson I, Stoilov I, Sarfarazi M, Schenkman JB. Toxicology. 2000;144:211–219. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(99)00209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zu X, Lu Z, Schenkman JB, Rusling JF. Langmuir. 1999;15:7372–7377. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lvov YM, Lu Z, Schenkman JB, Zu X, Rusling JF. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:4073–4080. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tarun M, Bajrami B, Rusling JF. Anal Chem. 2006;78:624–627. doi: 10.1021/ac0517996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lvov Y, Aviga K, Ichinose I, Kunitake T. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;22:6117–6123. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Omura T, Sato R. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:2379–2385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakajima M, Kobayashi K, Oshima K, Shimada N, Tokudome S, Chiba K, Yokoi T. Xenobiotica. 1999;29:885–898. doi: 10.1080/004982599238137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koley AP, Buters JTM, Robinson RC, Markowitz A, Friedman FK. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3149–3152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang TH, Gonzalez FJ, Waxman DJ. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;311:437–442. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.(a) Rusling JF, Zhang Z. In: Handbook of Surfaces and Materials. Nalwa HS, editor. Academic Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rusling JF, Zhang Z. In: Biomolecular Films. Rusling JF, editor. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2003. pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zu X, Lu Z, Schenkman JB, Rusling JF. Langmuir. 1999;15:7372–7377. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Munge B, Estavillo C, Schenkman JB, Rusling JF. Chem Bio Chem. 2003;4:82–89. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200390018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Devanesan PD, RamaKrishna NVS, Todorovic R, Rogan EG, Cavalieri EL, Jeong H, Jankowiak R, Small G. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5:302–309. doi: 10.1021/tx00026a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimada T, Gillam EMJ, Oda Y, Tsumura F, Sutter TR, Guengerich FP, Inoue K. Chem Res Toxicol. 1999;12:623–629. doi: 10.1021/tx990028s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh R, Gaskell M, Le Pla RC, Kaur B, Azim-Araghi AA, Roach J, Koukouves G, Souliotis VL, Kyrtopoulos SA, Farmer PB. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;19:868–878. doi: 10.1021/tx060011r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim JH, Stansbury KH, Walker NJ, Trush MA, Strickland PT, Sutter TR. Carcinogenisis. 1998;19:1847–1853. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.10.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Denissenko MF, Pao A, Tang MS, Pheifer GP. Science. 1996;274:430–432. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5286.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ross JA, Nesnow S. Mutat Res. 1999;424:155–166. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.(a) Wang IY, Rasmussen RE, Crocker TT. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;49:1142–1149. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(72)90332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Murray AW, Grover PL, Sims P. Chem Biol Interact. 1976;13:57–66. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(76)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hsu WT, Lin EJ, Fu PP, Harvey RG, Weiss SB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;88:251–257. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)91723-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guengerich FP. Carcinogenisis. 2000;21:345–351. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rochat B, Morsman JM, Murray GI, Figg WD, McLeod HL. J Pharm Exp Ther. 2001;296:537–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Buters JTM, Sakai S, Richter T, Pineau T, Alexander DL, Savas U, Doehmer J, Ward JM, Jefcoate CR, Gonzalez FJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1977–1982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information Available: Detailed experimental methodology, and 5 additional figures showing digitally reconstructed ECL array data for all cyt P450 enzyme films, ECL ratio plots for all single enzyme arrays, control ECL ratio plots, voltammetric data, and peak ratio plots for cyt P450 1A2, and MS data confirming formation of B[a]P-N7 adenine adduct. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.