Abstract

The hippocampus is especially vulnerable to seizure-induced damage and excitotoxic neuronal injury. This study examined the time course of neuronal death in relationship to seizure duration and the pharmacological mechanisms underlying seizure-induced cell death using low magnesium (Mg2+) induced continuous high frequency epileptiform discharges (in vitro status epilepticus) in hippocampal neuronal cultures. Neuronal death was assessed using cell morphology and Fluorescein diacetate-Propidium iodide staining. Effects of low Mg2+ and various receptor antagonists on spike frequency were assessed using patch clamp electrophysiology. We observed a linear and time-dependent increase in neuronal death with increasing durations of status epilepticus. This cell death was dependent upon extracellular calcium that entered primarily through the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor channel subtype. Neuronal death was significantly decreased by co-incubation with the NMDA receptor antagonists and was also inhibited by reduction of extracellular calcium (Ca2+) during status epilepticus. In contrast, neuronal death from in vitro status epilepticus was not significantly prevented by inhibition of other glutamate receptor subtypes or voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Interestingly this NMDA-Ca2+ dependent neuronal death was much more gradual in onset compared to cell death from excitotoxic glutamate exposure. The results provide evidence that in vitro status epilepticus results in increased activation of the NMDA-Ca2+ transduction pathway leading to neuronal death in a time dependent fashion. The results also indicate that there is a significant window of opportunity during the initial time of continuous seizure activity to be able to intervene, protect neurons and decrease the high morbidity and mortality associated with status epilepticus.

Keywords: Low Mg2+ model of status epilepticus, Neuronal death, NMDA-Ca2+ pathway

1. Introduction

Status epilepticus is a prolonged seizure condition representing a major medical and neurological emergency (Delorenzo, 2006; Lowenstein and Alldredge, 1998). The International League Against Epilepsy defines status epilepticus as continuous seizure activity or intermittent seizures without regaining consciousness lasting 30 minutes or longer (Delorenzo, 2006; Lowenstein and Alldredge, 1998) and recent evaluations have extended this definition to include seizure activity lasting even less than 30 minutes (DeLorenzo et al., 1999; Lowenstein et al., 1999; Treiman et al., 1998). The importance of status epilepticus is that it is associated with a significant morbidity and mortality despite aggressive treatment protocols and it can produce permanent brain damage, especially in the limbic system, resulting in cognitive dysfunction, epilepsy and other serious neurological conditions (Delorenzo, 2006; Delorenzo et al., 2005; Fountain, 2000; Lowenstein and Alldredge, 1998). The number of cases of status epilepticus in the United States alone has been estimated from epidemiological studies to be approximately 102,000–152,000 episodes per year and as many as 55,000 deaths per year have been attributed to status epilepticus (Delorenzo, 2006; Hauser, 1983). In addition, 12–30% of adult patients with a new diagnosis of epilepsy initially present with a first seizure that meets the definition of status epilepticus (Drislane, 2000; Fountain, 2000). It is important to investigate the basic mechanism and pharmacology of neuronal death produced by status epilepticus.

Significant progress has been made in recent years in the characterization of status epilepticus induced cell damage and neuronal tissue alteration after seizure activity (Fujikawa, 2005; Holmes, 2002; Sutula and Pitkänen, 2002). In vivo studies have correlated status epilepticus with capsase-induced apoptosis (Ekdahl et al., 2003), suppression of hippocampal neurogenesis in association with glucocorticoid levels and the frequency of seizure episodes (Liu et al., 2003), CA3 injury in the hippocampus due to GluR2B knockdown (Friedman et al., 2003), reorganization of alpha and beta integrin subunits (Fasen et al., 2003), and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor activation (Brandt et al., 2003). Meldrum and co-workers have demonstrated that status epilepticus can cause neuronal injury in ventilated and monitored animals even in the absence of underlying systemic physiological complications (Meldrum et al., 1973). However, in vivo studies of status epilepticus evaluating the molecular mechanisms of neuronal injury have had difficulty in clearly delineating the basic mechanisms involved in cell death because of the inherent problems associated with controlling the neuronal environment. In intact animal models, cellular responses to status epilepticus are associated with complex effects in multiple body systems, making it difficult to evaluate basic mechanisms. For example, changes in glucose utilization, hormonal production, extra-cellular fluid composition, and the involvement of other physiological processes may vary under different conditions inducing status epilepticus and alter the environment of neurons under study, complicating mechanistic studies in vivo.

This study was initiated to directly evaluate the effect of electrographic epileptiform discharges over time on neuronal viability and characterize the pharmacological mechanisms underlying status epilepticus-induced cell death in a controlled neuronal environment utilizing the well-established hippocampal neuronal culture model of in vitro status epilepticus. Exposure to a low magnesium (Mg2+) medium induces continuous high frequency epileptiform discharges in hippocampal neurons in culture. These high frequency discharges are produced because of the elimination of Mg2+ block of the ionotropic NMDA-receptor channels, which is normally reestablished after neuronal depolarization (Mayer and Westbrook, 1984). Lack of Mg2+ block of NMDA receptors produces repetitive depolarizations manifested as high frequency spiking characteristic of in vitro status epilepticus. In an elegant study, Mody et al. (Mody et al., 1987) suggested that reducing Mg2+ may produce a reduction in the electric field across the neuronal membrane by reducing surface charge screening causing a membrane depolarization. Further, Mangan and Kapur (Mangan and Kapur, 2004) have shown that an increased probability of transmitter release presynaptically, enhanced NMDA receptor-mediated excitability postsynaptically, and extent of neuronal interconnectivity contributes to initiation and maintenance of elevated network excitability upon exposure to low Mg2+ medium. The spike frequency and epileptiform discharges manifested upon exposure to a low Mg2+ medium are identical to the electrographic features of status epilepticus observed with animal models and in humans (Delorenzo et al., 2005; Lothman et al., 1991; Mangan and Kapur, 2004; Sombati and DeLorenzo, 1995). While the neuronal cultures do not manifest anatomical structures or behavioral seizures, the hippocampal neuronal culture model has the unique advantage of providing excellent control of the neuronal environment and allowing the application of powerful in vitro techniques to study biochemical, electrophysiological and molecular mechanisms underlying in vitro status epilepticus (Delorenzo et al., 2005; Deshpande et al., 2007a; Goodkin et al., 2005; Mangan and Kapur, 2004; Sombati and DeLorenzo, 1995). Thus, this model is ideally suited to evaluate the effects of electrographic epileptiform activity with synaptic activation on neuronal viability.

The results from this study indicate that low Mg2+ induced in vitro status epilepticus can cause neuronal cell death, but that cell death occurs over a prolonged time period measured in hours. The degree of status epilepticus induced neuronal death was linear, increased with increasing durations of exposure to continuous high frequency epileptiform discharges and was primarily dependent on NMDA receptor activated Ca2+ entry. The results indicate that status epilepticus induced neuronal death due to NMDA receptor activation takes much longer to initiate compared to stroke or excitotoxic glutamate induced cell death (Choi et al., 1987; Deshpande et al., 2007b). Understanding the basic mechanism and pharmacology of neuronal death induced by in vitro status epilepticus may provide important insights into obtaining a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms causing neuronal death in this common neurological condition. It may also lead to the development of novel therapeutic agents aimed at reducing the neuronal damage produced by prolonged seizure activity and ultimately decrease the high morbidity and mortality associated with status epilepticus.

2. Materials and Methods

All the reagents including fluorescein diacetate and propidium iodide were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted. Sodium pyruvate, minimum essential media containing Earle’s salts, fetal bovine serum and horse serum were obtained from Gibco-BRL (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA).

2.1 Hippocampal neuronal culture

All animal use procedures were in strict accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by Virginia Commonwealth University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Studies were conducted on primary mixed hippocampal neuronal cultures prepared as described previously with slight modifications (Deshpande et al., 2007a; Sombati and DeLorenzo, 1995). In brief, hippocampal cells were obtained from 2-day postnatal Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Frederick, MD) and plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells/cm2 onto 35-mm grid cell culture dishes (Nunc, Naperville, IL) previously coated with poly-L-lysine (0.05 mg/ml). Glial cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere and fed thrice weekly with glial feed (minimal essential media with Earle’s Salts, 25 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-Glutamine, 3 mM Glucose, and 10% fetal bovine serum). When confluent, glial beds were treated with 5-μM cytosine arabinoside for two days to curtail cell division. On the 13th day in vitro, the media was fully replaced with a 5% horse serum supplemented neuronal feed (composition given below) in preparation for neuronal plating on the following day. At this time, these cultures predominantly consisted of glial cells with few, if any, neurons. On the 14th day in vitro, hippocampal cell suspension was plated on these confluent glial beds at a density of 2 × 105 cells/cm2. Twenty-four hours after plating, cultures were treated with 5-μM cytosine arabinoside to inhibit non-neuronal growth. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere and fed twice weekly with neuronal feed (minimal essential media with Earle’s Salts, 25 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-Glutamine, 3 mM Glucose, 100 μg/ml transferrin, 5 μg/ml insulin, 100 μM putrescine, 3 nM sodium selenite, 200 nM progesterone, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.1% ovalbumin, 0.2 ng/ml triiodothyroxine and 0.4 ng/ml corticosterone supplemented with 5% horse serum). These mixed cultures were used for experiments from 13 days in vitro following neuronal plating through the life of the cultures.

2.2 Hippocampal neuronal culture model of status epilepticus

After 2-weeks, cultures were utilized for experimentation and status epilepticus was induced as described previously (Deshpande et al., 2007a; Sombati and DeLorenzo, 1995). Maintenance medium was replaced with physiological recording solution with or without MgCl2 containing (in mM): 145 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 10 HEPES, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose, and 0.002 glycine, pH 7.3, and osmolarity adjusted to 290 ± 10 mOsm with sucrose. Continuous epileptiform high-frequency bursts were induced by exposing neuronal cultures to physiological recording solution without added MgCl2 (low Mg2+). The status epilepticus continued until physiological recording solution containing 1 mM MgCl2 was added back to the cultures. Unless designated as low Mg2+ treatment, experimental protocols utilized physiological recording solution containing 1 mM MgCl2. For the perfusion studies, fresh low Mg2+ solution was constantly perfused over the culture plate using the gravity feed perfusion system (Warner Instrument Corp., Hamden, CT) at the rate of 2-mL/min. This procedure does not disrupt the neurons and provides a complete exchange of the experimental media every one minute.

2.3 Whole cell current clamp recordings

Whole cell current clamp recordings were performed using previously established procedures (Deshpande et al., 2007a; Sombati and DeLorenzo, 1995). Briefly, cell culture dishes were mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon Diaphot, Tokyo, Japan). Patch electrodes with a resistance of 2 to 4 mΩ were pulled on a Brown-Flaming P-80C electrode puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA), fire-polished and filled with a solution containing (in mM): 140 K+ gluconate, 1.1 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, and 10 Na-HEPES, pH 7.2, osmolarity adjusted to 290 ± 10 mOsm with sucrose. Whole-cell recordings were carried out using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) in a current-clamp mode. Data were digitized via Digidata 1322A (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and transferred to VHS tape using a PCM device (Neurocorder, New York, NY) and then played back on a DC-500 Hz chart recorder (Astro-Med Dash II, Warwick, RI). Electrophysiological data was obtained under both perfusion and non-perfusion conditions. The spike frequency did not alter between these two experimental protocols. The electrophysiological data represent recordings from the non-perfusion condition, wherein drug-containing solution was exchanged with maintenance media before start of the experiment.

2.4 Neuronal Death Assay

Neuronal death was assessed at various time-points after low-Mg2+ exposure using fluorescein diacetate (FDA)-propidium iodide (PI) microfluorometry (Deshpande et al., 2007c; Didier et al., 1990). Morphological assessment of the cultures was also carried out to determine neuronal viability (Deshpande et al., 2007c; Limbrick et al., 1995). Three randomly selected fields were marked and photographed. Both fluorescent and phase bright images were captured. These same fields were examined at various time points during continual exposure to low Mg2+ solution. Neurons labeled with FDA or PI were quantified by means of the Ultraview image analysis software package (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences) and percent neuronal death was calculated as the number of neurons labeled by PI divided by the sum of the number of neurons labeled by PI and those labeled by FDA. Fluorescent images were compared with phase bright images to confirm that only pyramid-shaped neurons were counted. To quantify neuronal cell death with this technique, cells in three randomly selected fields were counted manually and averaged per culture (approximately 18 to 25 neurons per field).

2.5 Data Analyses

Data are reported as mean ± S.E.M. Whole-cell patch clamp experiments and cell death analyses were carried out in parallel under similar experimental conditions in sister neuronal cultures. Neuronal culture plates were incubated in either low Mg2+ solution or low Mg2+ + drug containing solution for specified durations and then subjected to various experimental protocols at the end of the treatment. Thus, the drugs were applied during the low Mg2+ treatment for the duration of status epilepticus and chronically for both patch clamp and cell death experiments. Status epilepticus frequency was determined by counting individual epileptiform bursts and spikes over a recording duration of 5 min for each neuron analyzed before and after application of the drug. Neuronal cell death data were examined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-hoc Tukey test where appropriate. Paired t-tests were utilized to compare differences in neuronal death data between the fluorescent techniques and phase contrast microscopy. Each neuronal culture plate was treated as n = 1. All experiments had their own sham controls that were handled identically to the treatment condition. Equal number of sham controls and drug conditions were kept for each experiment. Net neuronal death was calculated by subtracting neuronal death observed in respective sham control groups in order to adjust for cell death due to handling artifacts. Data were analyzed using SigmaStat 2.0 and plotted using SigmaPlot 8.02 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

3. Results

3.1 Status epilepticus in hippocampal neuronal cultures

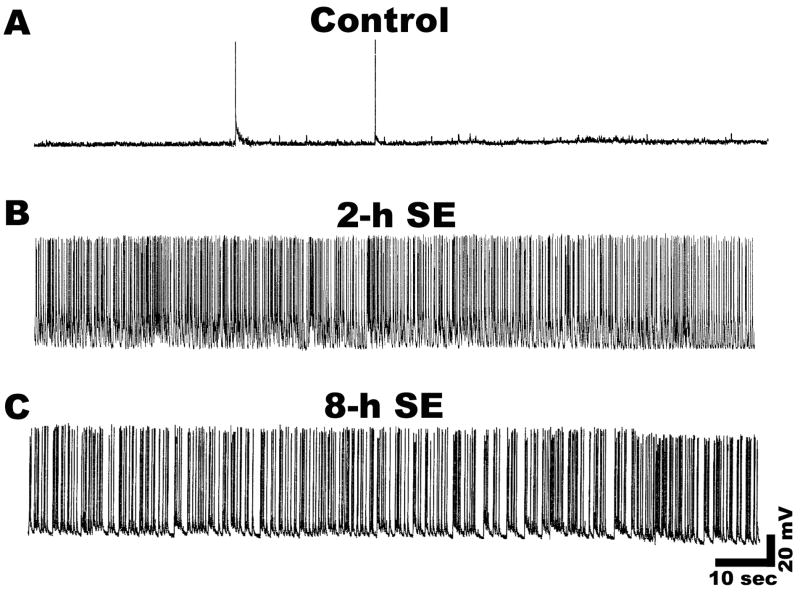

Treatment of hippocampal neurons in culture with low Mg2+ media induced continuous high frequency epileptiform activity characterized by repetitive burst discharges. Each burst was comprised of multiple spikes overlaying a depolarization shift identical to those observed in vivo during status epilepticus (Delorenzo et al., 2005; Lothman et al., 1991; Mangan and Kapur, 2004; Sombati and DeLorenzo, 1995). In marked contrast, recording from control neurons showed only occasional spontaneous action potentials (Fig. 1A). Figure 1B and C illustrates continuous recordings from a neuron after 2-h and 8-h of exposure to low Mg2+. The data demonstrate that the resultant high frequency continuous epileptiform discharges were sustained for the entire duration of low Mg2+ exposure. Expansion of the time scale indicated that spike frequency was greater than 3 Hz and lasted longer than 30 minutes and thus satisfied the definition criteria of status epilepticus (Hauser, 1983).

Figure 1.

Induction of continuous high frequency epileptiform discharges or in vitro status epilepticus like activity in cultured hippocampal neurons during exposure to low Mg2+ solution. A. Representative current clamp recording from a control neuron showing occasional spontaneous action potentials. B and C. Representative current clamp recordings showing induction of tonic high frequency epileptiform bursts (in vitro status epilepticus) from neurons subjected to 2 and 8-h of low Mg2+ treatment respectively. Tonic high frequency spiking was observed at all the durations of SE. The results shown were representative of over 20 recordings.

3.2 Duration of status epilepticus and neuronal cell death

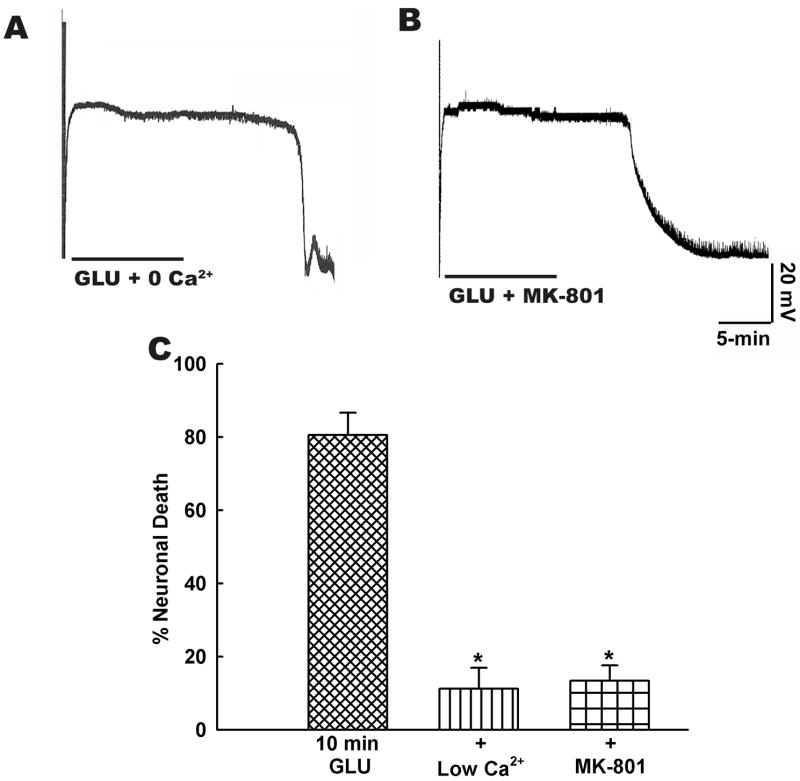

Having established that status epilepticus occurs throughout the duration of low Mg2+ exposure, we then investigated the effects of increasing durations of electrographic status epilepticus in a controlled neuronal environment on hippocampal cell death. In vitro status epilepticus was induced as described in the Materials and Methods by removing Mg2+ from the culture medium. Cell death was assessed using both FDA-PI staining and morphological measurements in the same marked field. Neuronal cultures were subjected to varying durations of status epilepticus which included 2, 4, 8 and 12-h exposures to low Mg2+. As shown in Fig. 2A, increasing the duration of status epilepticus caused a corresponding increase in neuronal death. There was a linear and time dependent increase in neuronal death with status epilepticus. Neuronal death increased from approximately 30% to 100% when the duration of low Mg2+ exposure was increased from 2 to 12-h. Thus, all the neurons die if status epilepticus continues for long enough. Neuronal death assessment using the FDA-PI intravital dye staining method or the morphological examination technique were consistent and produced essentially identical determinations of the degree of neuronal death and the results from these two techniques were not statistically divergent (paired t-test). Thus, we carefully compared the effects of continuous epileptiform discharges on cell death to control for the time and conditions of handling by using identical conditions except for the replacement of physiological Mg2+.

Figure 2.

Increase in neuronal cell death with increasing durations of in vitro status epilepticus. A. Cultures were exposed to various durations of low Mg2+ treatment ranging from 2 to 12-h and neuronal death was assessed using the FDA-PI intravital dye staining method and the morphological technique in the same marked field. Neuronal death was found to be dependent on the duration of status epilepticus in culture and increased with increasing durations of status epilepticus. Differences between the two techniques to evaluate cell death were not statistically significant. B. Accumulation of glutamate or other seizure- released metabolites into the media does not contribute to neuronal cell death. Continuous perfusion of culture plate with fresh low Mg2+ solution throughout the duration of status epilepticus using gravity feed perfusion system prevented possible accumulation of glutamate or other substances in the culture plate. Duration of status epilepticus ranged from 2 to 12-h and low Mg2+ solution was perfused throughout the experiment. Black circles (●) indicate sham controls. Open circles (○) represent percent cell death from non-perfusion status epilepticus cultures. Black triangles (▼) represent percent cell death from continuous perfusion status epilepticus cultures. Control and treated neurons were subjected to similar perfusion protocol. Significant differences were observed for all the time points of status epilepticus between sham and low Mg2+ treated neurons (n = 6–10, *P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test). However, there were no significant differences in cell death between perfusion and non-perfusion conditions (n = 6–10, P = 0.7). Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M.

Status epilepticus is known to cause elevations in extracellular levels of glutamate (Smolders et al., 1997; Ueda et al., 2002). However, in vivo evidence indicates this accumulation should be minimal (Bruhn et al., 1992; Millan et al., 1993). Prolonged exposure to elevated extracellular glutamate is known to kill the neurons via excitotoxic mechanisms (Choi et al., 1987; Deshpande et al., 2007a; Limbrick et al., 1995). In order to rule out involvement of neurotoxic effects of glutamate or other seizure-released metabolites, we performed experiments wherein fresh low Mg2+ solution was continuously perfused over the culture plate throughout the duration of status epilepticus. This technique prevents the build up of glutamate or metabolites released during the in vitro status epilepticus providing a more controlled environment for the neurons. Both control and status epilepticus neurons were treated identically. As shown in Fig. 2B, similar to non-perfusion experiments, we observed a linear and time-dependent increase in neuronal death despite continuous perfusion of low Mg2+ solution. Differences in neuronal cell death between sham control and low Mg2+ conditions (perfusion and non-perfusion) were significant for all the low Mg2+ exposure durations (p < 0.001, n = 6–10). Interestingly, cell death under perfusion conditions was lower than non-perfusion conditions, but it was not statistically significant (p = 0.81). These experiments indicate that status epilepticus alone, and not the build up of glutamate or other seizure-released metabolites were responsible for neuronal death. Cell death in non status epilepticus control cultures (n = 6–10) was estimated around 10–15% and represented the cell death associated with handling procedures involved with washing neurons and exposure to the control recording solution (Fig. 2B). For the subsequent experiments, cell death from sham controls was subtracted from drug treatment groups to correctly represent net neuronal death due to low Mg2+ exposure alone.

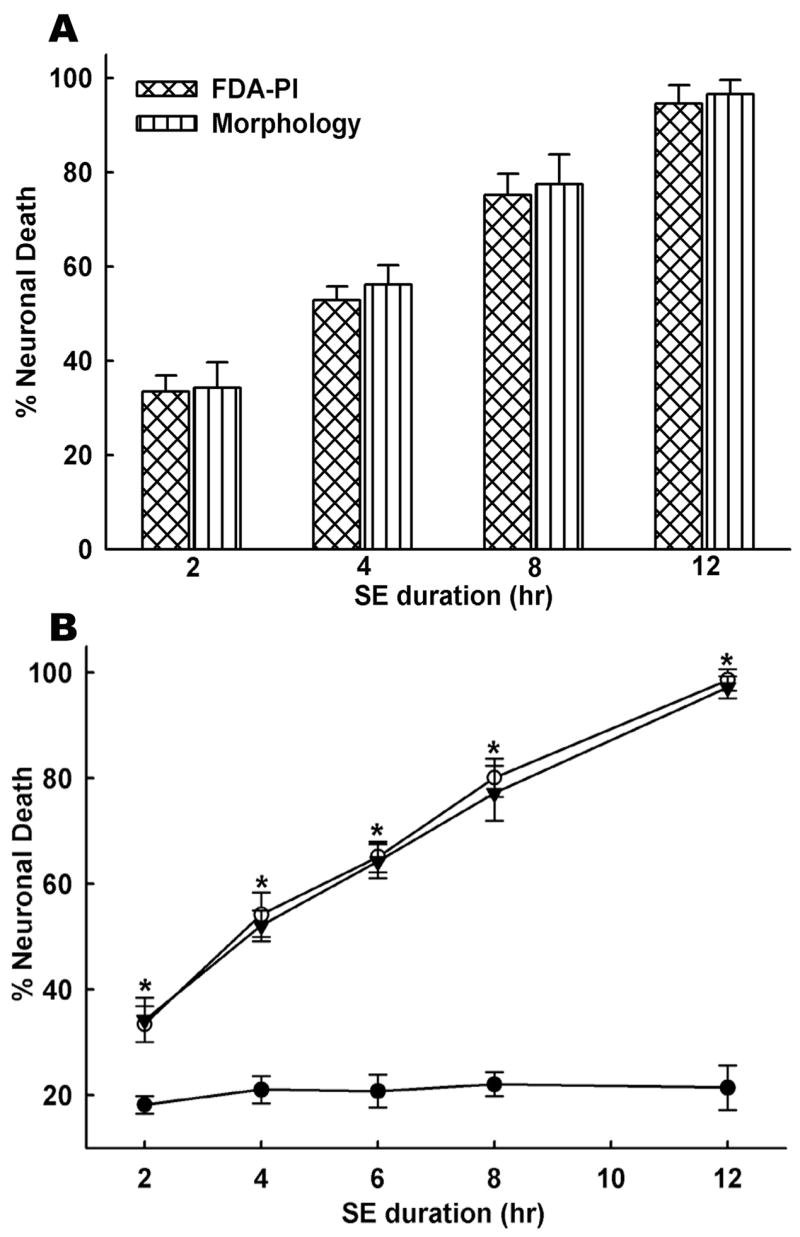

3.3 Role of Ca2+ in status epilepticus induced neuronal death

Calcium is a major signaling molecule and has been implicated to play an important role in epileptogenesis and neuronal death in various acute neurological diseases (Delorenzo et al., 2005). To determine if Ca2+ was a major component in status epilepticus induced neuronal death, the concentration of extracellular Ca2+ was manipulated. This method has been routinely used to investigate the possible role of extracellular Ca2+ in neuronal excitotoxicity (Deshpande et al., 2007a; Limbrick et al., 1995). Reduced extracellular Ca2+ (0.2 mM) during low Mg2+ treatment significantly attenuated net neuronal death when compared to 8-h status epilepticus controls (Fig. 3A). Status epilepticus durations of 8-h with 2 mM Ca2+ (n = 9) resulted in 60.2 ± 5.03% neuronal death. In cultures treated with low Ca2+ solution for 8-h (n = 6), net neuronal death was determined to be 4.05% ± 3.03% when controlled for sham treatment. Thus, there was a significant (p < 0.001) attenuation of net neuronal death in the presence of low extracellular Ca2+ compared to the 8-h status epilepticus controls with normal extracellular Ca2+. Lowering extracellular Ca2+ had no effects on the expression of low Mg2+ induced high frequency epileptiform discharges (Fig. 3B). These experiments indicate that status epilepticus induced neuronal death is dependent upon influx of extracellular Ca2+.

Figure 3.

In vitro status epilepticus induced neuronal death is dependent upon extracellular calcium. A. Neuronal death assessment revealed that lowering extracellular Ca2+ significantly attenuated net neuronal cell death compared to 8-h status epilepticus alone group (n = 6, * P<0.001, one-way ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test). In contrast, percent neuronal death was not significantly different between 8-h status epilepticus and nifedipine or ethosuximide treated cultures (n = 6, P = 0.8). Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. B. Representative current clamp recording from a neuron subjected to low Mg2+ induced status epilepticus in the presence of low Ca2+ (0.2 mM). Lowering extracellular Ca2+ had no effect on low Mg2+ induced high frequency spiking. C. Representative recording from a neuron treated with nifedipine (10 μM) during low Mg2+ induced status epilepticus. Similar to low Ca2+ condition, nifedipine treatment didn’t affect low Mg2+ induced high frequency spiking.

In order to investigate the route of this Ca2+entry, we used concentrations of well-characterized voltage gated Ca2+ channels inhibitors shown to be effective under our physiological conditions (Deshpande et al., 2007a). Cadium (Cd2+) is a non-selective Ca2+ channel blocker, however recent reports have indicated that this metal ion can initiate apoptosis and necrosis in neuronal cultures (Lopez et al., 2003). This could have potentially confounded our cell death results. Therefore, we inhibited the Ca2+ channels with the more selective agents that would have been inhibited by the general effects of Cd2+ and avoided the possible toxic effects of this metal. We first blocked L-type Ca2+ channels that have the highest conductance amongst voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Treatment with nifedipine (5 μM, n = 6) appeared to slow down low Mg2+ induced high frequency spiking (Fig. 3C and Table 1), but it did not significantly reduce neuronal death compared to untreated 8-h status epilepticus controls (Fig. 3A). T type voltage gated Ca2+ channels that are blocked by ethosuximide (Sun et al., 2004) are also reported to be upregulated following status epilepticus and have been implicated in epilepsy.

Table 1.

Spike frequency before and during low-Mg2+ treatment in the presence or absence of various pharmacological manipulations

| Treatment Condition | Spike frequency |

|---|---|

| Control | 0 |

| Low Mg2+ | 11 ± 3.4 |

| + 0 mM Ca2+ | 12 ± 4.2 |

| + Nifedipine (5 μM) | 9 ± 3.2 |

| + Ethosuximide (1 mM) | 11 ± 4.1 |

| + CNQX (10 μM) | 10 ± 2.8 |

| + NBQX (10 μM) | 8 ± 4.1 |

| + mCPG (250 μM) | 10 ± 3.2 |

| + d-APV (25 μM) | 11 ± 3.8 |

| + MK-801 (10 μM) | 10 ± 4.4 |

| + ω-conotoxin (1 μM) | 0 |

| + Tetrodotoxin (1 μM) | 0 |

Data are represented as the mean ± S.E.M. of spike frequency during low-Mg2+ treatment for various experimental conditions (n = 5–7). Spike frequency was determined as described in Materials and Methods section. There were no statistical differences between the spike frequencies of these conditions (Student’s t test).

Ethosuximide (1mM, n = 5) did not significantly prevent cell death due to status epilepticus in this model (Fig. 3A). It was not possible to evaluate the effects of ω-conotoxin because electrophysiological studies showed that this agent, similar to tetrodotoxin, effectively blocked synaptic transmission and also prevented low Mg2+ induced high frequency spiking (Table 1). Therefore the role of presynaptically located N or P/Q type Ca2+ channels cannot be completely dismissed. However, inhibition of status epilepticus using tetrodotoxin or ω–conotoxin in the presence of 0 Mg2+ demonstrated that low Mg2+ alone was not causing neuronal death. The lack of effects of nifedipine and ethosuximide on reducing cell death from status epilepticus support the interpretation that Ca2+ entry through voltage gated Ca2+ channels is not playing a significant role in causing cell death.

3.4 Role of glutamate receptor subtypes in status epilepticus induced neuronal death

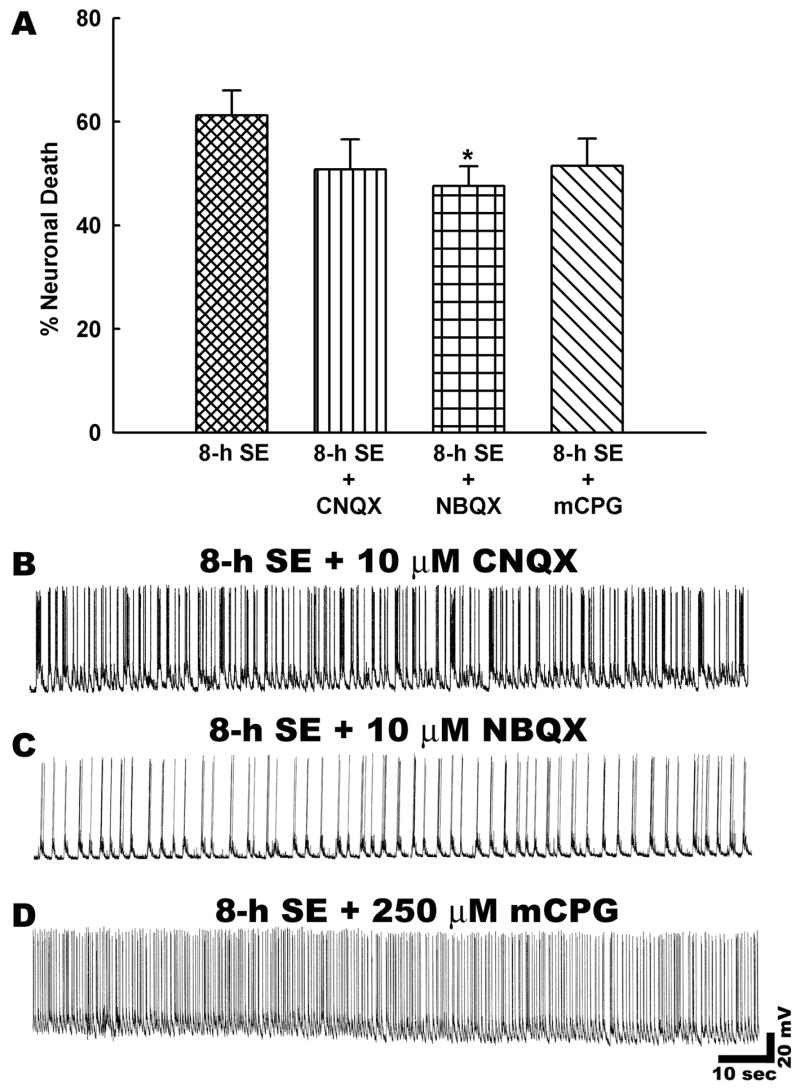

To examine the possibility that the excessive entry of extracellular Ca2+ through glutamate receptor activated channels was involved in status epilepticus induced neuronal death; in vitro status epilepticus was induced in the presence of various glutamate receptor subtype antagonists. Treatment with the AMPA/kainate glutamate receptor antagonist 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX, 10 μM, n = 6) had no significant effects on the percentage of neuronal death compared with 8-h status epilepticus cultures (Fig. 4A). Exposure to the metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist (S)-α-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (m-CPG, 250 μM, n = 6) did not significantly reduce neuronal death after 8-h of status epilepticus (Fig. 4D). The AMPA/kainate glutamate receptor antagonist 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo[f]quinoxaline-2,3-dione (NBQX, 10 μM, n = 6) did show a small decrease in neuronal death from 8-h of status epilepticus compared to controls (p < 0.05). In the current-clamp studies, while treatment with CNQX and m-CPG had no effects on status epilepticus associated spiking, NBQX appeared to considerably slow down low Mg2+ induced high frequency epileptiform spiking (Fig. 4B–D and Table 1). This is in line with our previous observations that NBQX produced greater decreases in intracellular Ca2+ levels compared to CNQX during low Mg2+ induced status epilepticus (DeLorenzo et al., 1998). Thus, this reduction of the severity of electrographic epileptiform discharges may have contributed to its minor, but significant effect in reducing neuronal death.

Figure 4.

Role of glutamate receptor subtypes in status epilepticus induced neuronal death. A. Neuronal death assessment revealed that there were no statistically significant differences between CNQX and mCPG treated cultures and 8-h status epilepticus alone cultures (n = 6, P = 0.7). However, a small but significant reduction in neuronal death was observed upon NBQX treatment (n = 6, *P < 0.05, One-way ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test). Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. B–D. Representative current clamp recordings from neurons subjected to treatment with various glutamate receptor antagonists during low Mg2+ induced status epilepticus like activity. Treatment with AMPA/KA receptor antagonist CNQX (10 μM) or NBQX (10 μM) did slow down low Mg2+ induced high frequency spiking. But the spike frequency was still >3 Hz that meets the criteria of status epilepticus. Similarly, the metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist mCPG (250 μM) also had no effects on status epilepticus like activity.

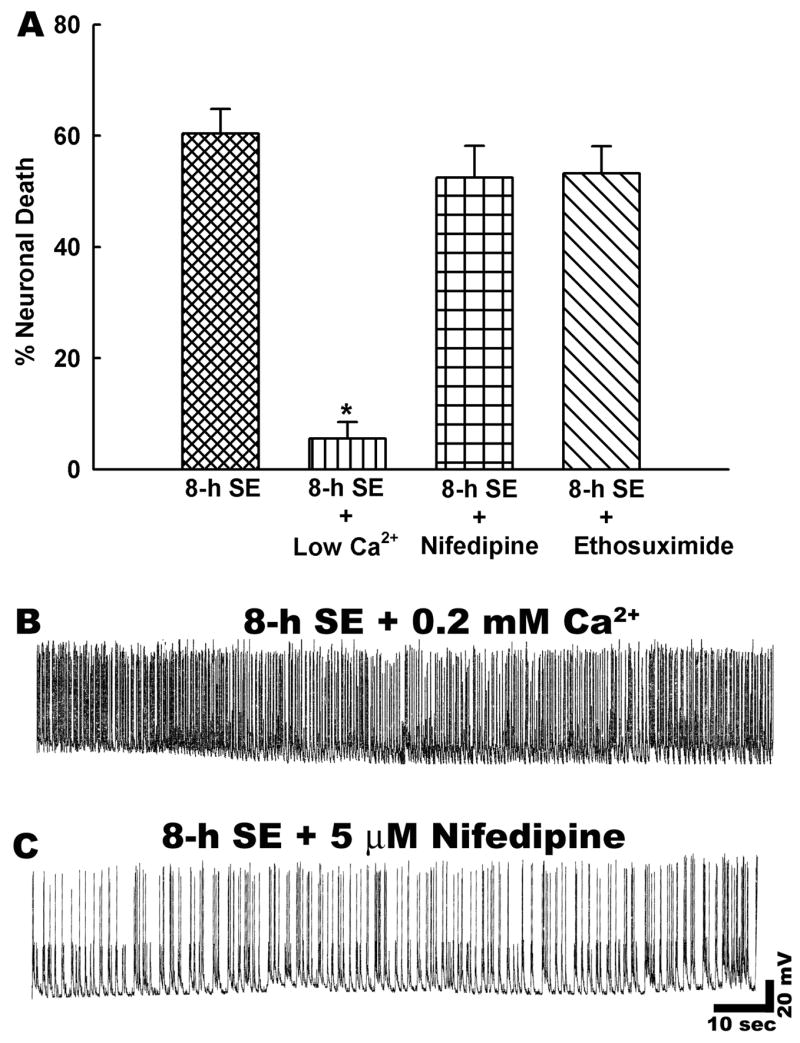

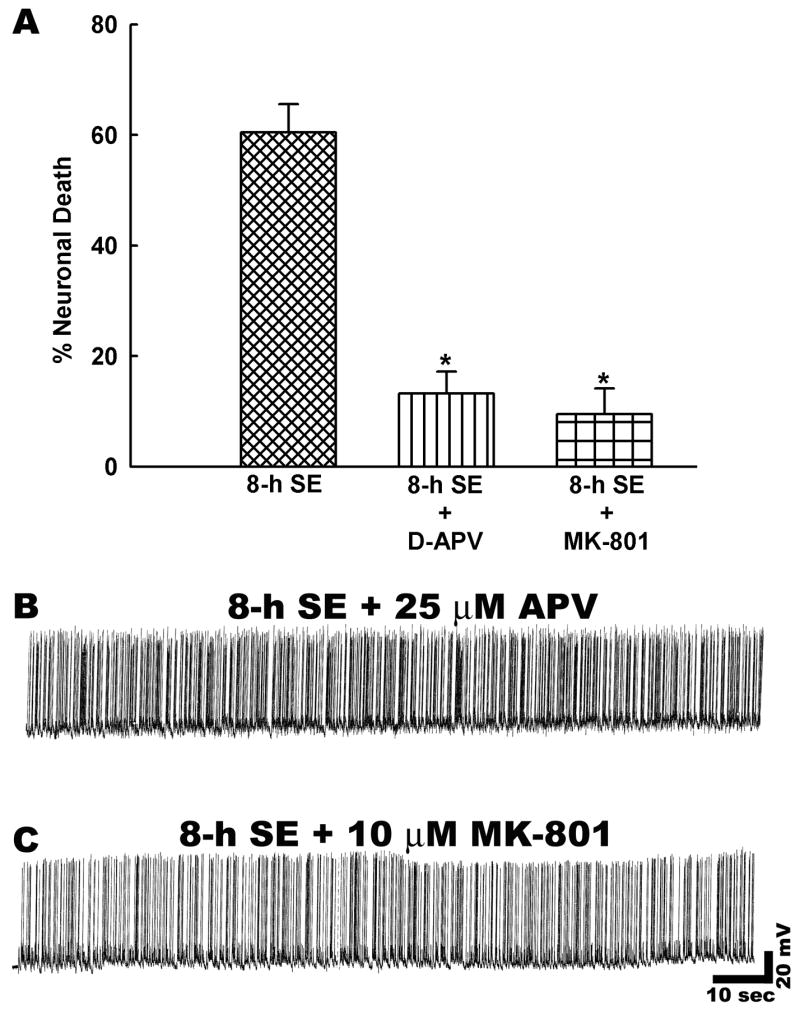

3.5 Status epilepticus induced neuronal death is NMDA receptor dependent

Treatment with the NMDA receptor antagonist 5-methyl-10,11-dihydro-5-H-dibenzocyclohepten-5,10-imine maleate (MK-801, 10 μM, n = 6) produced a marked reduction in net neuronal death to 9.5 ± 3.36%, a figure that represented approximately an 80% decrease in neuronal death compared to 8-h status epilepticus controls (Fig. 5A). Prolonged status epilepticus is associated with increases in extracellular glutamate that could depolarize the neurons. MK-801 is a voltage-dependent blocker of NMDA-receptor ion channel and its ability to block is limited under the depolarized condition. Although our electrophysiological studies did not reveal depolarization in neurons undergoing prolonged status epilepticus (membrane potentials: control = −62.5 ± 3.5 mV, 2-h low Mg2+ = −60.2 ± 4.2 mV, 8-h low Mg2+ = −59.8 ± 3.1 mV), to confirm our findings with MK-801, we also performed experiments with a competitive NMDA receptor antagonist, D-APV. Treatment with 2-amino-5-phosphonovalerate (D-APV, 25 μM, n = 6) also showed a marked decrease in net neuronal death (Fig. 5A). Co-incubation with D-APV throughout the duration of 8-h status epilepticus reduced net neuronal death to 13.2 ± 2.02%. The reductions in neuronal death produced by D-APV and MK-801 were both statistically significant (p < 0.001). Treatments with APV or MK-801 had no effects on the expression of low Mg2+ induced high frequency epileptiform discharges (Fig. 5B and C and Table 1). These results demonstrate that during in vitro status epilepticus, extracellular Ca2+ that enters neurons through the NMDA receptor pathway is coupled to the molecular cascades that initiate neuronal death.

Figure 5.

Status epilepticus induced net neuronal death is NMDA receptor dependent. A. There was a significant reduction in net neuronal death when NMDA receptor antagonists APV (25 μM) or MK-801 (10 μM) were present throughout the duration of status epilepticus as compared to 8-h status epilepticus controls (n = 6, * P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test). Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M. B–C. Representative current clamp recordings from neurons subjected to treatment with NMDA receptor antagonists during low Mg2+ induced status epilepticus. Treatment with APV (25 μM) or MK-801 (10 μM) had no effects on low Mg2+ induced high frequency spiking.

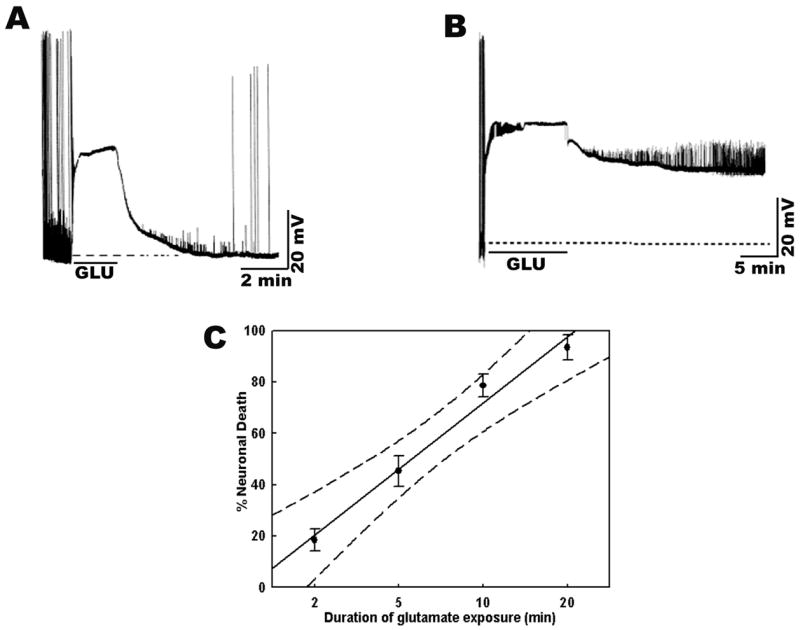

3.6 Time course and mechanism of cell death following stroke-like injury in vitro

Application of high concentrations of glutamate to hippocampal neuronal cultures is an established model for studying stroke-like injury in vitro (Choi et al., 1987; Deshpande et al., 2007a; Limbrick et al., 1995). We utilized this model to investigate the time course and mechanism of cell death following stroke-like injury in vitro. Following glutamate exposure, there was a massive depolarization of the neuronal membrane and the neuron stayed depolarized as long as glutamate was present in the extracellular medium. Recovery from this depolarized state was contingent upon duration of glutamate exposure. Thus, following 2 min glutamate exposure neurons recovered to baseline membrane potentials (Fig. 6A). However, a 10 min glutamate exposure produced a state of irreversible membrane depolarization known as extended neuronal depolarization (END) (Fig. 6B). This END state correlates with impending neuronal cell death (Deshpande et al., 2007a; Limbrick et al., 1995). Indeed, as shown in Fig. 6C, bath application of glutamate (500 μM glutamate, 10 μM glycine, n = 5–7) produced a time dependent increase in neuronal cell death. Thus, 2-min glutamate exposure produced around 20% cell death. Following 5-min glutamate stimulation approximately 50% cell death was observed. A 10-min glutamate exposure produced around 80% cell death and 20-min glutamate stimulation caused greater than 90% of cell death. Linear regression analysis revealed a strong correlation (r2 = 0.98) between duration of glutamate exposure and neuronal cell death (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Time course of neuronal cell death following stroke-like injury in vitro. A. Current clamp recording from a neuron subjected to glutamate (500 μM + 10 μM glycine) for a short duration (5-min). The neuron shows rapid depolarization when exposed to glutamate, stays depolarized as long as glutamate is present in the bath solution and after 5-mins when washed with control-recording solution regains its resting membrane potential. B. Current clamp recording from a neuron subjected to glutamate (500 μM + 10 μM glycine) for a long duration (10-min). This constitutes the excitotoxic insult. Despite removal of glutamate after the 10-min period, the neuron stays depolarized for as long as recording is continued. This constitutes the extended neuronal depolarization (END) phase. C. Increasing durations of glutamate exposure (500 μM glutamate along with 10 μM glycine dissolved in physiological recording solution containing 1 mM Mg2+) caused a corresponding increase in percent neuronal death as assessed using the FDA-PI intravital dye staining method. Linear regression analysis of neuronal cell death and duration of glutamate exposure gave an r2-value of 0.98. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence interval limits.

Further, in agreement with previously established results (Choi et al., 1987; Deshpande et al., 2007a; Limbrick et al., 1995) we observed that stimulation of NMDA-Ca2+ dependent pathway was primarily responsible for the glutamate-induced cell death in vitro. Thus, glutamate application in the presence of low Ca2+ medium or MK 801 (10 μM) didn’t prevent the early depolarization but prevented development of END (Fig. 7A and 7B). Similarly, as shown in Fig. 7C, the cell death was significantly (p< 0.001, n= 5–7) reduced when glutamate was applied in the presence of NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 (10 μM) or when glutamate was applied in a medium containing low Ca2+ (0.2 mM). Thus, while neuronal cell death following status epilepticus-like or stroke-like injury in vitro followed a similar mechanism, unlike status epilepticus induced cell death, the neuronal death following glutamate injury had a much quicker onset ranging in minutes rather than hours.

Figure 7.

Mechanism of neuronal cell death following stroke-like injury in vitro. Representative current-clamp recordings from neurons demonstrating that excitotoxic glutamate injury (500 μM glutamate, 10 μM glycine, 10-min duration) produced in medium containing A. no added extracellular Ca2+ or B. in the presence of NMDA channel inhibitor MK-801 during glutamate exposure prevents development of END phase following termination of glutamate insult. C. Neuronal death following excitotoxic glutamate exposure (500 μM glutamate, 10 μM glycine, 10-min duration) was dependent upon activation of NMDA receptor-Ca2+ dependent pathway. There was a significant reduction in neuronal death when glutamate injury was produced in the presence of low Ca2+ (0.2 mM). Similar reduction in neuronal death was also observed NMDA receptor antagonist MK-801 (10 μM) was present throughout the duration of glutamate exposure (n = 5–7, * P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA, post-hoc Tukey test). Data are represented as mean ± S.E.M.

4. Discussion

The results from this study indicate that electographic epileptiform discharges in hippocampal neuronal cultures and the resultant excessive synaptic activity can induce cell death in a time dependent manner in an in vitro model of status epilepticus that controls for any effects of environmental influences. We observed that the degree of neuronal death was linear and directly correlated with increasing durations of continuous high frequency epileptiform discharges induced by treatment with low Mg2+. Status epilepticus induced neuronal death was also found to be dependent upon extracellular Ca2+, since reducing the driving force for Ca2+ entry by lowering extracellular Ca2+ during status epilepticus significantly attenuated neuronal death. Status epilepticus mediated neuronal death was reduced by NMDA receptor channel inhibition, while neuroprotection afforded by inhibition of non-NMDA glutamate receptor subtypes or voltage gated Ca2+ channels appeared to be minor. In contrast to glutamate excitotoxicity and stroke induced cell death, status epilepticus mediated activation of NMDA receptors required hours to induce significant cell death. Our results are consistent with data obtained from in vivo models and clinical studies demonstrating that the neuronal death is dependent upon duration of status epilepticus (Duncan, 2002; Holmes, 2002; Towne et al., 1994) and offers a unique model to investigate the time dependent effects of status epilepticus on neuronal viability.

Neuronal injury secondary to status epilepticus is the consequence of excessive neuronal excitability and synaptic activity with high-frequency epileptiform discharges, resulting in depolarizing shifts of membrane potential, free radical production, neuronal metabolic overload and elevations in extracellular glutamate (reviewed in: Delorenzo et al., 2005; Lipton, 1999; Lowenstein and Alldredge, 1998). Our data supports the previous research that showed neuronal death after status epilepticus to be excitotoxic in nature (Abele et al., 1990; Delorenzo et al., 2005; Fountain, 2000; Fujikawa, 2005; Meldrum, 1991; Peterson et al., 1989). Thus, glutamate mediated activation of NMDA receptors results in excessive influx of Ca2+ that triggers various NMDA receptor-coupled neurotoxic signaling cascades, some of which induce neuronal death, including the activation of proteases (Araujo et al., 2005), neuronal nitric oxide synthase (Chuang et al., 2007; Dawson and Dawson, 1996), ceramides (Mikati et al., 2003) and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (Mandir et al., 2000). These variables may combine in a positive feed-forward cycle resulting in increased levels of intracellular Ca2+, with subsequent energy failure and neuronal death (Fujikawa, 2005). The neuroprotection we observed upon NMDA receptor antagonism or lowering extracellular Ca2+ could possibly result from inhibition of these neurotoxic cascades. It will be interesting to investigate these possibilities in future studies. These results are in line with earlier in vivo studies from our lab (Rice and DeLorenzo, 1998) and those reported by others (Fujikawa et al., 1994), that NMDA receptor inhibition did not stop on-going status epilepticus activity, but the blockade of NMDA receptor signaling pathways was sufficient to attenuate status epilepticus induced neuronal death.

Microdialysis studies in both animals and humans have documented that prolonged seizure activity during status epilepticus is associated with significant elevations in extracellular glutamate (Ueda et al., 2002; Wilson et al., 1996). Thus, it is important to determine if accumulation of extracellular glutamate in the culture solution contributes to the status epilepticus induced neuronal death in our hippocampal neuronal culture model. While continuous perfusion of fresh low Mg2+ solution throughout the duration of status epilepticus does not remove the rapidly generated synaptic glutamate during status epilepticus, it prevents build up of glutamate or other seizure-induced metabolites that diffuse out of the synaptic cleft and accumulate over time in the culture media. Despite the continuous perfusion of fresh extracellular media, there was no significant decrease in neuronal death during status epilepticus. This finding is further supported by the observation that sustained, prolonged status epilepticus caused by electrical stimulation of the perforant pathway alone can damage postsynaptic neurons (Olney et al., 1983; Sloviter, 1983). In addition, it has also been reported that increasing durations of kainic acid induced status epilepticus to the point of neuronal injury cause cell death in the absence of a measurable increase in extracellular glutamate concentration (Tanaka et al., 1996). Our results are also in agreement with animal (Fujikawa, 2005; Gorter et al., 2003; Holmes, 2002; Pitkanen et al., 2002) and human data (Duncan, 2002; Liu et al., 2005; Thom et al., 2005) that indicate neuronal death is associated with acute status epilepticus and not with the subsequent chronic spontaneous recurrent seizures. Indeed post-mortem studies in humans have shown that neuronal loss produced upon accidental ingestion of domoic acid induces status epilepticus in the absence of systemic complications or preexisting epilepsy that produces neuronal loss, which is similar in distribution to what is observed in clinical status epilepticus patients or in animal models of status epilepticus (Fujikawa et al., 2000).

In concordance with previously published studies, status epilepticus induced neuronal death in this model was found be dependent on extracellular Ca2+ and occurred via the activation of NMDA receptor pathway (Abele et al., 1990; Meldrum, 1991; Peterson et al., 1989). However, status epilepticus induced activation of the NMDA receptor pathway required approximately 8–10 hours to produce over 80% cell death in comparison to glutamate induced cell death in cultured neurons that requires only 10–15 minutes to achieve similar amounts of cell death (Choi et al., 1987; Deshpande et al., 2007b; Hardingham et al., 2002). Sattler et al., have reported that synaptically and extrasynaptically activated NMDARs are equally capable of excitotoxicity. In addition, the relative contributions vary with the location of extracellular excitotoxin accumulation (Sattler et al., 2000). Thus, further studies are needed to evaluate the time dependent difference in cell death produced by these different injuries.

Development of the “excitotoxic hypothesis” in the 1980’s (Olney, 1985) led to the production of many NMDA receptor antagonists including some used in this study. However, later observations that these agents were neurotoxic resulted in a decreased interest towards NMDA receptor antagonism as a potential therapeutic avenue (Olney, 1994). While the interest has been rekindled in recent years with development of ketamine and memantine and other NMDA receptor antagonists, the progress has been slow (Chen and Lipton, 2006; Kohl and Dannhardt, 2001). The hippocampal neuronal culture model of in vitro status epilepticus provides a powerful model that could allow for rapid screening of neuroprotective agents and suggests that further investigations into the use of NMDA receptor antagonists should be considered in the treatment of status epilepticus. The pharmacological evidence used in this paper allowed us to selectively inhibit various ion channels and receptors without stopping status epilepticus. It was important to be able to demonstrate that NMDA receptor activation was an important mediator of cell death during status epilepticus. Inhibition of the status epilepticus spike discharges by using tetrodotoxin or ω–conotoxin in the presence of 0 Mg2+ demonstrated that 0 Mg2+ alone was not causing neuronal death. This paper provides direct evidence that cell death can be produced by continuous electrographic epileptiform events through activation of the NMDA receptor system. The longer time course required to cause NMDA receptor-Ca2+ dependent neuronal death due to in vitro status epilepticus offers a wide therapeutic window to develop novel therapeutic interventions to prevent brain injury due to status epilepticus.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grants RO1NS051505 and RO1NS052529, and award UO1NS058213 from the National Institutes of Health CounterACT Program through the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke to RJD. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the federal government. In addition, the Milton L. Markel Alzheimer’s Disease Research Fund and the Sophie and Nathan Gumenick Neuroscience Research Fund also funded this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abele AE, Scholz KP, Scholz WK, Miller RJ. Excitotoxicity induced by enhanced excitatory neurotransmission in cultured hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Neuron. 1990;4:413–419. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90053-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo IM, Xapelli S, Gil JM, Mohapel P, Petersen A, Pinheiro PS, Malva JO, Bahr BA, Brundin P, Carvalho CM. Proteolysis of NR2B by calpain in the hippocampus of epileptic rats. Neuroreport. 2005;16:393–396. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200503150-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt C, Potschka H, Loscher W, Ebert U. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor blockade after status epilepticus protects against limbic brain damage but not against epilepsy in the kainate model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience. 2003;118:727–740. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruhn T, Cobo M, Berg M, Diemer NH. Limbic seizure-induced changes in extracellular amino acid levels in the hippocampal formation: a microdialysis study of freely moving rats. Acta Neurol Scand. 1992;86:455–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1992.tb05123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HSV, Lipton SA. The chemical biology of clinically tolerated NMDA receptor antagonists. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1611–1626. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW, Maulucci-Gedde M, Kriegstein AR. Glutamate neurotoxicity in cortical cell culture. J Neurosci. 1987;7:357–368. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-02-00357.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang YC, Chen SD, Lin TK, Liou CW, Chang WN, Chan SHH, Chang AYW. Upregulation of nitric oxide synthase II contributes to apoptotic cell death in the hippocampal CA3 subfield via a cytochrome c/caspase-3 signaling cascade following induction of experimental temporal lobe status epilepticus in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:1263–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Nitric oxide actions in neurochemistry. Neurochem Int. 1996;29:97–110. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(95)00149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorenzo RJ. Epidemiology and clinical presentation of status epilepticus. Adv Neurol. 2006;97:199–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorenzo RJ, Garnett LK, Towne AR, Waterhouse EJ, Boggs JG, Morton L, Choudhry MA, Barnes T, Ko D. Comparison of Status Epilepticus with Prolonged Seizure Episodes Lasting from 10 to 29 Minutes. Epilepsia. 1999;40:164–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLorenzo RJ, Pal S, Sombati S. Prolonged activation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-Ca2+ transduction pathway causes spontaneous recurrent epileptiform discharges in hippocampal neurons in culture. Proc Natal Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14482–14487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delorenzo RJ, Sun DA, Deshpande LS. Cellular mechanisms underlying acquired epilepsy: the calcium hypothesis of the induction and maintainance of epilepsy. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;105:229–266. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande LS, Blair RE, Ziobro JM, Sombati S, Martin BR, DeLorenzo RJ. Endocannabinoids block status epilepticus in cultured hippocampal neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007a;558:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande LS, Limbrick DD, Jr, Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ. Activation of a novel injury-induced calcium-permeable channel that plays a key role in causing extended neuronal depolarization and initiating neuronal death in excitotoxic neuronal injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007b;322:443–452. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.123182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande LS, Lou JK, Mian A, Blair RE, Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ. In vitro status epilepticus but not spontaneous recurrent seizures cause cell death in cultured hippocampal neurons. Epilepsy Res. 2007c;75:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didier M, Heaulme M, Soubrie P, Bockaert J, Pin JP. Rapid, sensitive, and simple method for quantification of both neurotoxic and neurotrophic effects of NMDA on cultured cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci Res. 1990;27:25–35. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490270105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drislane FW. Presentation, Evaluation, and Treatment of Nonconvulsive Status Epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2000;1:301–314. doi: 10.1006/ebeh.2000.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan JS. Seizure-induced neuronal injury: Human data. Neurology. 2002;59:15S–20. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.9_suppl_5.s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekdahl CT, Zhu C, Bonde S, Bahr BA, Blomgren K, Lindvall O. Death mechanisms in status epilepticus-generated neurons and effects of additional seizures on their survival. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;14:513–523. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fasen K, Elger CE, Lie AA. Distribution of alpha and beta integrin subunits in the adult rat hippocampus after pilocarpine-induced neuronal cell loss, axonal reorganization and reactive astrogliosis. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2003;106:319–322. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0733-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountain NB. Status epilepticus: risk factors and complications. Epilepsia. 2000;41(Suppl 2):S23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LK, Veliskova J, Kaur J, Magrys BW, Liu H. GluR2(B) knockdown accelerates CA3 injury after kainate seizures. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:733–750. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.7.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa DG. Prolonged seizures and cellular injury: Understanding the connection. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa DG, Daniels AH, Kim JS. The competitive NMDA receptor antagonist CGP 40116 protects against status epilepticus-induced neuronal damage. Epilepsy Res. 1994;17:207–219. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(94)90051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa DG, Itabashi HH, Wu A, Shinmei SS. Status Epilepticus-Induced Neuronal Loss in Humans Without Systemic Complications or Epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2000;41:981–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkin HP, Yeh JL, Kapur J. Status Epilepticus Increases the Intracellular Accumulation of GABAA Receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5511–5520. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0900-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorter JA, Pereira PMG, van Vliet EA, Aronica E, da Silva FHL, Lucassen PJ. Neuronal Cell Death in a Rat Model for Mesial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Is Induced by the Initial Status Epilepticus and Not by Later Repeated Spontaneous Seizures. Epilepsia. 2003;44:647–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.53902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham GE, Fukunaga Y, Bading H. Extrasynaptic NMDARs oppose synaptic NMDARs by triggering CREB shut-off and cell death pathways. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:405–414. doi: 10.1038/nn835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser WA. Status epilepticus: frequency, etiology, and neurological sequelae. Adv Neurol. 1983;34:3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes GL. Seizure-induced neuronal injury: Animal data. Neurology. 2002;59:3S–6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.9_suppl_5.s3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl BK, Dannhardt G. The NMDA Receptor Complex: A Promising Target for Novel Antiepileptic Strategies. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:1275–1289. doi: 10.2174/0929867013372328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limbrick DD, Churn SB, Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ. Inability to restore resting intracellular calcium levels as an early indicator of delayed neuronal cell death. Brain Res. 1995;690:145–156. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton P. Ischemic cell death in brain neurons. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1431–1568. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Kaur J, Dashtipour K, Kinyamu R, Ribak CE, Friedman LK. Suppression of hippocampal neurogenesis is associated with developmental stage, number of perinatal seizure episodes, and glucocorticosteroid level. Exp Neurol. 2003;184:196–213. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RSN, Lemieux L, Bell GS, Sisodiya SM, Bartlett PA, Shorvon SD, Sander JWAS, Duncan JS. Cerebral Damage in Epilepsy: A Population-based Longitudinal Quantitative MRI Study. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1482–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.51603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez E, Figueroa S, Oset-Gasque MJ, Gonzalez MP. Apoptosis and necrosis: two distinct events induced by cadmium in cortical neurons in culture. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:901–911. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lothman EW, Bertram EH, 3rd, Stringer JL. Functional anatomy of hippocampal seizures. Prog Neurobiol. 1991;37:1–82. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(91)90011-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein DH, Alldredge BK. Status epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:970–976. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804023381407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein DH, Bleck T, Macdonald RL. It’s Time to Revise the Definition of Status Epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1999;40:120–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandir AS, Poitras MF, Berliner AR, Herring WJ, Guastella DB, Feldman A, Poirier GG, Wang ZQ, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. NMDA But Not Non-NMDA Excitotoxicity is Mediated by Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8005–8011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08005.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan PS, Kapur J. Factors underlying bursting behavior in a network of cultured hippocampal neurons exposed to zero magnesium. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:946–957. doi: 10.1152/jn.00547.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer ML, Westbrook GL. Mixed-agonist action of excitatory amino acids on mouse spinal cord neurones under voltage clamp. J Physiol. 1984;354:29–53. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum B. Excitotoxicity and epileptic brain damage. Epilepsy Res. 1991;10:55–61. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(91)90095-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum BS, Vigouroux RA, Brierley JB. Systemic factors and epileptic brain damage. Prolonged seizures in paralyzed, artificially ventilated baboons. Arch Neurol. 1973;29:82–87. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1973.00490260026003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikati MA, Abi-Habib RJ, El Sabban ME, Dbaibo GS, Kurdi RM, Kobeissi M, Farhat F, Asaad W. Hippocampal Programmed Cell Death after Status Epilepticus: Evidence for NMDA-Receptor and Ceramide-Mediated Mechanisms. Epilepsia. 2003;44:282–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.22502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MH, Chapman AG, Meldrum BS. Extracellular amino acid levels in hippocampus during pilocarpine-induced seizures. Epilepsy Res. 1993;14:139–148. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(93)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody I, Lambert JD, Heinemann U. Low extracellular magnesium induces epileptiform activity and spreading depression in rat hippocampal slices. J Neurophysiol. 1987;57:869–888. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.57.3.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW. Excitatory transmitters and epilepsy-related brain damage. Int Rev Neurobiol. 1985;27:337–362. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7742(08)60561-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW. Neurotoxicity of NMDA receptor antagonists: an overview. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1994;30:533–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olney JW, deGubareff T, Sloviter RS. “Epileptic” brain damage in rats induced by sustained electrical stimulation of the perforant path. II. Ultrastructural analysis of acute hippocampal pathology. Brain Res Bull. 1983;10:699–712. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(83)90038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Neal J, Cotman C. Development of N-methyl-D-aspartate excitotoxicity in cultured hippocampal neurons. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1989;48:187–195. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(89)90075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen A, Nissinen J, Nairismagi J, Lukasiuk K, Grohn OH, Miettinen R, Kauppinen R. Progression of neuronal damage after status epilepticus and during spontaneous seizures in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Prog Brain Res. 2002;135:67–83. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(02)35008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice AC, DeLorenzo RJ. NMDA receptor activation during status epilepticus is required for the development of epilepsy. Brain Res. 1998;782:240–247. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01285-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler R, Xiong Z, Lu WY, MacDonald JF, Tymianski M. Distinct Roles of Synaptic and Extrasynaptic NMDA Receptors in Excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2000;20:22–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00022.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloviter RS. “Epileptic” brain damage in rats induced by sustained electrical stimulation of the perforant path. I. Acute electrophysiological and light microscopic studies. Brain Res Bull. 1983;10:675–697. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(83)90037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolders I, Khan GM, Manil J, Ebinger G, Michotte Y. NMDA receptor-mediated pilocarpine-induced seizures: characterization in freely moving rats by microdialysis. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1171–1179. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sombati S, DeLorenzo RJ. Recurrent spontaneous seizure activity in hippocampal neuronal networks in culture. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:1706–1711. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.4.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun DA, Sombati S, Blair RE, DeLorenzo RJ. Long-lasting alterations in neuronal calcium homeostasis in an in vitro model of stroke-induced epilepsy. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutula T, Pitkänen A. Summary: Seizure-induced damage in experimental models. Prog Brain Res. 2002;135:133–135. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(02)35030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Graham SH, Simon RP. The role of excitatory neurotransmitters in seizure-induced neuronal injury in rats. Brain Res. 1996;737:59–63. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00658-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thom M, Zhou J, Martinian L, Sisodiya S. Quantitative post-mortem study of the hippocampus in chronic epilepsy: seizures do not inevitably cause neuronal loss. Brain. 2005;128:1344–1357. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towne AR, Pellock JM, Ko D, DeLorenzo RJ. Determinants of mortality in status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 1994;35:27–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiman DM, Meyers PD, Walton NY, Collins JF, Colling C, Rowan AJ, Handforth A, Faught E, Calabrese VP, Uthman BM, Ramsay RE, Mamdani MB. A comparison of four treatments for generalized convulsive status epilepticus. Veterans Affairs Status Epilepticus Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:792–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809173391202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda Y, Yokoyama H, Nakajima A, Tokumaru J, Doi T, Mitsuyama Y. Glutamate excess and free radical formation during and following kainic acid-induced status epilepticus. Exp Brain Res. 2002;147:219–226. doi: 10.1007/s00221-002-1224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CL, Maidment NT, Shomer MH, Behnke EJ, Ackerson L, Fried I, Engel J. Comparison of seizure related amino acid release in human epileptic hippocampus versus a chronic, kainate rat model of hippocampal epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 1996;26:245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(96)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]