Abstract

Egg activation is the process that modifies mature, arrested oocytes so that embryo development can proceed. One key aspect of egg activation is the cytoplasmic polyadenylation of certain maternal mRNAs to permit or enhance their translation. wispy (wisp) maternal-effect mutations in Drosophila block development during the egg-to-embryo transition. We show here that the wisp gene encodes a member of the GLD-2 family of cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerases (PAPs). The WISP protein is required for poly(A) tail elongation of bicoid, Toll, and torso mRNAs upon egg activation. In Drosophila, WISP and Smaug (SMG) have previously been reported to be required to trigger the destabilization of maternal mRNAs during egg activation. SMG is the major regulator of this activity. We report here that SMG is still translated in activated eggs from wisp mutant mothers, indicating that WISP does not regulate mRNA stability by controlling the translation of smg mRNA. We have also analyzed in detail the very early developmental arrest associated with wisp mutations. Pronuclear migration does not occur in activated eggs laid by wisp mutant females. Finally, we find that WISP function is also needed during oogenesis to regulate the poly(A) tail length of dmos during oocyte maturation and to maintain a high level of active (phospho-) mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs).

MATURE oocytes of most animals are arrested at a species-specific stage of meiosis until certain events occur that convert the oocyte to a state that can undergo embryogenesis. Prior to these events, the mature oocyte is developmentally “poised”: it contains maternal mRNAs and other molecules that are required for embryogenesis. The process that transitions the oocyte to become competent for further development is called egg activation. In vertebrates and marine invertebrates, egg activation is triggered by fertilization. Entry of the sperm causes an increase of free calcium in the egg cytoplasm, which triggers the completion of meiosis (reviewed in Ducibella et al. 2006; Parrington et al. 2007). In Drosophila, egg activation occurs independently of fertilization and appears to be triggered by mechanical stress experienced by the egg when it passes through the female reproductive tract during ovulation (Heifetz et al. 2001; Horner and Wolfner 2008a). A calcium-dependent signaling pathway is involved in activation of Drosophila eggs (Horner et al. 2006; Takeo et al. 2006), and many of the events of Drosophila egg activation downstream of the initial trigger appear analogous to those in other animals.

Activation events include modifications in egg coverings, resumption and completion of meiosis, degradation of some maternal mRNAs, a decrease in mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activity, and changes in the cytoskeleton (reviewed in Horner and Wolfner 2008b). An additional crucial aspect of egg activation is the polyadenylation of some maternal transcripts that initiates their translation. In Drosophila, transcripts subject to regulation by polyadenylation during egg activation include the bicoid, Toll, and torso mRNAs. These mRNAs encode proteins that are involved in defining embryo polarity. The protein products of these mRNAs are first detected only after egg activation is triggered (Driever and Nusslein-Volhard 1988; Hashimoto et al. 1988; Casanova and Struhl 1989). Initiation of the translation of these mRNAs correlates with an increase in the length of their poly(A) tails (Salles et al. 1994).

Polyadenylation of mRNA takes place initially in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells, but maintenance and regulation of the poly(A) tail occurs in the cytoplasm (Sachs et al. 1997). Cytoplasmic polyadenylation is a key regulatory mechanism that controls the function of maternal mRNAs during the early development of Xenopus oocytes (reviewed in Mendez and Richter 2001). A cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase (PAP) called GLD-2, first identified in Caenorhabditis elegans, functions within a protein complex to facilitate cytoplasmic polyadenylation (Wang et al. 2002; Barnard et al. 2004). In Xenopus oocytes, the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein (CPEB) recognizes the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element in the 3′-UTR of the mRNA (Hake and Richter 1994; Stebbins-Boaz et al. 1996). CPEB associates with the cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor (CPSF), which recognizes another 3′-UTR element, AAUAAA (Dickson et al. 1999; Mendez et al. 2000; Dickson et al. 2001). GLD-2 is thus recruited to mRNA through interaction with CPEB and CPSF (Barnard et al. 2004). Several mRNAs required for oocyte maturation in Xenopus, such as those encoding cyclin B and Mos, are controlled by this machinery (Sheets et al. 1995; Stebbins-Boaz et al. 1996; Barkoff et al. 2000). Another GLD-2-binding partner in C. elegans, GLD-3, is necessary for PAP function, being the subunit that allows the GLD-2-GLD-3 complex to bind to RNA (Wang et al. 2002). Cytoplasmic polyadenylation factors are conserved among eukaryotes and some of these factors have also been identified to be important in the Drosophila germline. For example, Orb, the Drosophila homolog of CPEB, is necessary during oogenesis (Lantz et al. 1994; Castagnetti and Ephrussi 2003). However, it has not yet been made clear whether GLD-2 and other GLD-2-associated factors also play a role in Drosophila development.

Here we show that the Drosophila wispy (wisp) gene encodes a predicted cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase that is a member of the GLD-2 class of proteins. wisp maternal-effect mutations were previously reported to cause defects in bicoid mRNA localization and in microtubule-based events of female meiosis, leading to very early developmental arrest (Brent et al. 2000). Early embryos of wisp mutant females were also known to fail to destabilize maternal transcripts, a phenotype that suggested a defect in egg activation (Tadros et al. 2003). To further dissect wisp's possible role in egg activation, we identified the molecular nature of the wisp gene and assessed the ability of wisp mutants to undertake various events of egg activation. We found that the WISP protein sequence contains a conserved PAP/25A-associated domain, and our yeast two-hybrid experiments showed that WISP can associate with Bicaudal-C (Bic-C), a Drosophila GLD-3 homolog. We also found that wisp mutant embryos are defective in the addition of poly(A) to several maternal mRNAs. Embryos from wisp mutant mothers also fail to initiate mitosis after fertilization. This problem appears to result in part from abnormalities that occur during the completion of female meiosis in the absence of wisp function: the acentriolar microtubule-organizing center between meiosis II spindles is reduced in size, pronuclei fail to appose, and the polar body rosette does not form. WISP function is also required in oocytes for the normal, regulated polyadenylation of dmos mRNA and, potentially through this action, for phosphorylation (activation) of MAPKs in mature oocytes prior to egg activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila stocks and complementation tests:

Oregon-R was used as the wild-type stock. wisp41/FM6, wisp248/FM6, and wisp249/FM6 (Tadros et al. 2003) were kindly provided by W. Tadros and H. Lipshitz (Hospital for Sick Children, University of Toronto). wisp12-3147/FM0, described by Brent et al. (2000), was obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Bloomington, IN). sra687/FM6 and Df(3R)sbd45, mwh1 e1/TM6 were previously described by Horner et al. (2006). P-element insertion lines for CG32663, CG1886, CG10353, CG15738, CG15737, CG2467, and CG2471—used for complementation tests as well as Df(1)RA47/FM7c used for making wisp41 and wisp248 hemizygotes—were from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. We crossed males of P-insertion lines to wisp41/+ or wisp248/+ virgin females. Fertility of the wisp/P-insertion daughters of this cross was scored to assess complementation.

Embryo collection, fixation, and staining:

Laid eggs were collected as previously described (Horner et al. 2006). Three- to 4-day-old virgin females were mated either to wild-type Oregon-R males to produce fertilized eggs (embryos) or to spermless males [the sons of tud1 bw sp mothers (Boswell and Mahowald 1985)] to generate unfertilized activated eggs.

Fertilized and unfertilized eggs were collected on grape juice plates for the desired period of time and washed off the plates with egg wash buffer (0.4% NaCl, 0.2% Triton X-100). Hereafter, “0- to 1-hr embryos” will refer to fertilized eggs collected 0- to 1-hr post egg deposition, and other collection lengths will be described in a similar fashion. “Eggs” will refer to eggs laid by females mated to wild-type males, which may be fertilized or unfertilized, and “unfertilized eggs” will refer to eggs laid by females mated to spermless males (described above), unless otherwise indicated. For immunofluorescence analysis, collected eggs were dechorionated in 50% bleach for 2 min, rinsed thoroughly with water, and then permeabilized with heptane and fixed immediately in cold methanol. Fixed eggs were washed in 1× PBST (137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 10.1 mm Na2HPO4, 1.8 mm KH2PO4, 0.1% Triton X-100) and incubated at 4° overnight with a 1:200 dilution of a mouse anti-α-tubulin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis) in 1× PBST. RNaseA (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis) was added to a final concentration of 5 μg/ml. Secondary antibody [Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at a dilution of 1:200] was then added for 2 hr at room temperature. Propidium iodide (Invitrogen) was added at a concentration of 10 μg/ml to stain DNA. Samples were either mounted in 75% glycerol containing 940 mm n-propyl gallate or washed with methanol and mounted in benzyl benzoate:benzyl alcohol (2:1). Staining in fertilized and unfertilized eggs was analyzed using confocal microscopy [Leica TCS SP2 system equipped with an argon–krypton laser and coupled to a Leica DMRBE microscope (Leica Microsystems)]. Leica software was used to collect images and, where appropriate, to project multiple optical sections into a single image and to overlay images.

RNA extraction and RT–PCR:

Total RNA was extracted from adult flies and 0- to 2-, 2- to 4-, 4- to 6-, or 6- to 24-hr embryos using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). PCR reactions were performed with a High Fidelity kit (Roche Applied Science). Primer sequences were as follows: wisp P1 upper, 5′-ACTATCGCAAGTCGGAATCG, and P1 lower, 5′-AGTTGCGCCTATGCTCGATGGAC; wisp P2 upper, 5′-TACCAGGCGCTAAACACCCAG, and P2 lower, 5′-TTAGGCGACATGCGCTGCAG. The transcript for ribosomal protein RPL32 (Fiumera et al. 2005), amplified using primers 5′-CCGCTTCAAGGGACAGTATC and 5′-GACAATCTCCTTGCGCTTCT, was used as a control for the quality and quantity of the cDNAs used for RT–PCR.

Western blot analysis:

Samples from ovarian oocytes and 0- to 15-min or 0- to 2-, 2- to 4-, 4- to 6-, 6- to 24-hr embryos were prepared for Western blotting and processed as in Sackton et al. (2007). A polyclonal anti-WISP antibody was generated by methods described in Ravi Ram et al. (2005). Briefly, a glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion of the carboxy-terminal 411 amino acids of the predicted WISP protein was purified from Escherichia coli cells and used to immunize rabbits (Cocalico Biologicals, Reamstown, PA). Serum was first run through a Sepharose 4B column (Sigma) coupled with GST protein and then affinity purified with the GST-WISP fusion protein. The purified antibody was used at 1:2000 dilution to probe Western blots. Anti-SMG antibody, a kind gift from W. Tadros and H. Lipshitz, was diluted 1:10,000 (Tadros et al. 2007). Anti-α-tubulin antibody (Sigma, catalog no. T5168) was diluted 1:10,000. Anti-MAPK antibodies were used as previously described (Sackton et al. 2007).

Yeast two-hybrid analysis:

We cloned full-length coding sequences from WISP and Bic-C (Mahone et al. 1995) into vectors of the Matchmaker yeast two-hybrid system (CLONTECH, Mountain View, CA). In-frame fusions of each coding region were generated in both the DNA-binding domain vector pGBKT7 and the activation domain vector pGADT7. Yeast cells cotransformed with pGBKT7 and pGADT7 derivatives were grown on −Trp −Leu synthetic medium and tested for growth on −Trp −Leu −His and −Trp −Leu −His −Ade synthetic media.

Poly(A) test assay:

Oocytes were dissected from 3- to 4-day-old virgin control and virgin wisp mutant females. Zero to 1-hr embryos were collected as described above and aged at room temperature for 1 or 2 hr to get 1- to 2- or 2- to 3-hr embryos, respectively. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen), and 1 μg total RNA from each sample was used for the poly(A) test (PAT) assay. PCR-based PAT assays were performed as described in Salles and Strickland (1995). Briefly, total RNA from each sample was incubated in the presence of 20 ng 5′-phosphorylated oligonucleotide p(dT)18 to saturate the poly(A) tails of the mRNAs. The p(dT)18 was then ligated together in the presence of 10 units (Weiss) of T4 DNA ligase (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD) to generate a complementary copy of the poly(A) tail. Two hundred nanograms of oligo(dT)12 anchor was added and ligated to the 5′-end of the poly(T) strand. The mRNAs were then reverse transcribed (as described above) to synthesize the PAT cDNAs. PCR was performed on the PAT cDNAs using a gene-specific primer and the oligo(dT)12 anchor to test the length of the poly(A) tail of a specific mRNA. Sequences of primers specific for bicoid, Toll, and torso and the sequence of the oligo(dT)12 anchor were described by Salles et al. (1994). The sequence of our primer specific for dmos is 5′-GCTGAAGCATGAGCTGGAATTC. PCR products from the PAT assays were run on 2% agarose gels or 8% acrylamide gels. Gels were stained with 0.5 μg/ml ethidium bromide.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The wisp gene encodes a member of the GLD-2 poly(A) polymerase family:

To identify the wisp gene at the molecular level, we carried out complementation analysis with mutations in 10F1-7, the polytene chromosome region to which wisp had been previously mapped (Brent et al. 2000; Tadros et al. 2003). We tested for complementation between wisp mutant alleles (wisp41 and wisp248) and the 7 (of 24 total) predicted genes in the 10F1-7 region for which P-element insertion lines were available. One line, P{SUPor-P}CG15737KG05287, fails to complement both wisp alleles. The P element in this line is inserted in the coding region of CG15737, 105 bp downstream of CG15737's start codon according to the latest annotation of the Drosophila genome (http://www.flybase.org). Our results suggest that CG15737 corresponds to the wisp gene.

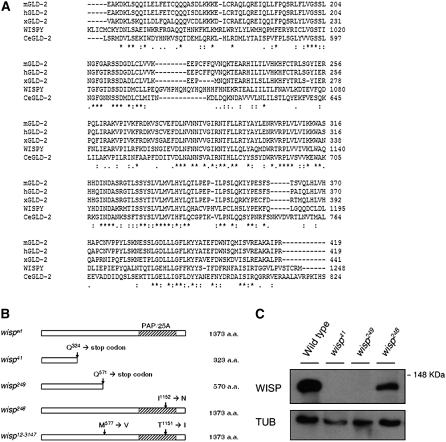

According to the latest annotation of the Drosophila genome, CG15737 has one predicted open reading frame (ORF) that encodes a protein of 1373 amino acids. BLAST searches revealed that the predicted CG15737 protein has a consensus PAP/25A-associated domain, which is conserved in poly(A) polymerases. As shown in Figure 1A, the predicted CG15737 protein sequence is homologous to GLD-2 proteins from other animals: CeGLD-2 in C. elegans (Wang et al. 2002), xGLD-2 in Xenopus laevis (Barnard et al. 2004), mGLD-2 in mice, and hGLD-2 in humans (Kwak et al. 2004; Kwak and Wickens 2007). CG15737 shares 51–56% similarity in its PAP/25A-associated domain with the previously characterized GLD-2 proteins.

Figure 1.—

Wild-type and mutant protein sequences of WISP. (A) Amino acid sequence of the predicted PAP domain of WISP was aligned against those of GLD-2 proteins of C.elegans, Xenopus, humans, and mice. Identical or similar residues between the sequences are indicated with an asterisk or dot(s), respectively. (B) Schematic of wisp alleles. wisp41 and wisp249 have nonsense mutations in the coding region that result in truncated proteins of 323 aa and 570 aa, respectively. wisp248 has a point mutation at position 1152, resulting in a Ile-to-Asp change. wisp12-3147 has point mutations at positions 577 and 1151, which result in Met-to-Val and Thr-to-Ile substitutions, respectively. (C) Western blot analysis. Ovaries were dissected from wild-type, wisp41/wisp41, wisp248/wisp248, and wisp249/wisp249 females. Ovarian protein extracts were separated by SDS–PAGE, blotted, and probed with affinity-purified polyclonal anti-WISP directed against the 411 aa C-term part of the protein or with anti-α-tubulin (loading control; TUB). A protein of ∼140 kDa is detected in ovarian extracts of wild-type and wisp248/wisp248 females. This band is absent in ovarian extracts of wisp41/wisp41 and wisp249/wisp249 females.

To confirm the assignment of CG15737 as wisp, we sequenced CG15737 in four wisp mutant alleles: wisp41, wisp248, wisp249, and wisp12-3147. As shown in Figure 1B, all four alleles have molecular lesions in the predicted ORF of CG15737. wisp41, wisp248, and wisp249 were induced in the same genetic background (Tadros et al. 2003), so the different molecular lesions found in these alleles do not represent background mutations. wisp41 and wisp249 are single-base-pair changes that cause nonsense mutations resulting in truncated proteins. wisp248 is a point mutation that changes a conserved isoleucine (Ile) to asparagine (Asp) in the predicted PAP/25A domain. wisp12-3147 has two point mutations. One is a change from threonine (Thr) to isoleucine in a residue of the PAP/25A domain adjacent to the one mutated in wisp248; the other is a methionine- (Met) to-valine (Val) change outside the conserved domain.

We generated an antibody against WISP (see materials and methods). Our antibody detects a protein of ∼140 kDa in ovarian protein extracts of wild-type and wisp248/wisp248 females, but not in ovarian protein extracts of wisp41/wisp41 and wisp249/wisp249 females, consistent with our finding that the wisp41 and wisp249 mutations result in truncated proteins lacking the C-terminal epitopes recognized by this antibody (Figure 1C).

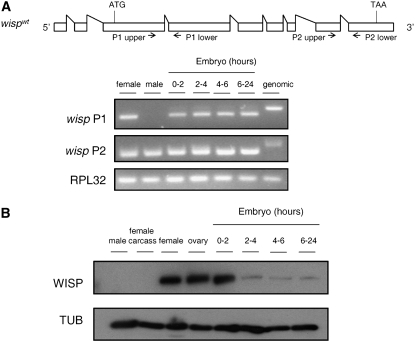

To determine the expression pattern of wisp, we performed RT–PCR for wisp mRNA using two sets of primers specific for two different regions of the predicted transcript. Transcripts of wisp are detected in adult flies and throughout embryogenesis with the primer set P2, which amplifies a region near the 3′-end of the coding sequence (Figure 2A). The primer set P1, located toward the 5′-end of the gene, amplifies a PCR product of the predicted size in cDNAs made from female adult flies and all stages of deposited eggs or embryos, but does not amplify any PCR product in cDNA made from male flies. These results indicate the presence of wisp mRNA in females and in eggs/embryos and suggest that males lack the long form of this RNA predicted by bioinformatics. Since we focus here on the roles of WISP in the female germline, we did not investigate the structure of the male transcript further. To assay for the presence of WISP protein, we performed Western blot analysis with our WISP antibody. We find that high levels of WISP protein are present in adult female flies, ovarian oocytes, and 0- to 2-hr embryos. WISP protein is not detected in adult male flies or in nonovarian female tissues (Figure 2B). Low levels of WISP protein are also detected in late-stage embryos.

Figure 2.—

Presence of wisp transcripts and proteins. (A) Total RNAs were extracted from 3- to 4-day-old wild-type adult female and male flies or laid embryos of the indicated ages. mRNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA for PCR analysis. RPL32 primers were used as positive control. Two different sets of wisp primers shown in the context of the wisp mRNA as predicted in FlyBase (http://www.flybase.org) were used to detect wisp transcripts. A PCR product for wisp P1 is present in all samples examined except male cDNA. PCR products for both wisp P2 and RPL32 are present in all samples. (B) Ovaries were dissected from 3- to 4–day-old virgin females and the females' remaining somatic tissues were used as the female carcass sample. Total protein extracts from these two samples, wild-type adult flies and laid embryos of the indicated ages, were separated by SDS–PAGE, blotted, and probed for anti-WISP and anti-α-tubulin (TUB; loading control).

The WISP protein can interact with Bicaudal-C:

Sequence comparisons suggest that WISP's primary amino acid sequence, like those of other GLD-2 proteins (Kwak et al. 2004; Kwak and Wickens 2007), does not contain any predicted RNA recognition motifs. In C. elegans, binding of GLD-2 to mRNA is instead mediated by an RNA-binding protein called GLD-3 (Wang et al. 2002). In Xenopus, xGLD-2 is found in a cytoplasmic polyadenylation complex in which CPEB and CPSF are also present (Barnard et al. 2004). Drosophila has homologs of some of these proteins, and Drosophila's CPEB (named Orb) has been shown to interact with Bic-C, the Drosophila homolog of GLD-3 (Castagnetti and Ephrussi 2003). Bic-C, which is present in oocytes and early embryos like wisp, is required for anterior–posterior patterning during oogenesis (Mahone et al. 1995; Saffman et al. 1998). In the germline, Bic-C has been recently reported to regulate the expression of specific mRNAs by participating in control of their poly(A) tail length (Chicoine et al. 2007).

Using the yeast two-hybrid assay, we found that WISP can interact with Bic-C (Table 1). WISP in an activation domain (AD) fusion can interact with Bic-C in a binding domain (BD) fusion but not with the BD alone (that is, with an empty vector). We observed interaction only between WISP and Bic-C in one orientation because BD-WISP was not detected on Western blots, suggesting that BD-WISP is either not expressed or not stable in yeast (data not shown). The two-hybrid interaction that we observed between WISP and Bic-C suggests that WISP in Drosophila might function, analogous to the GLD-2 proteins in other animals, by forming a protein complex with other RNA-binding proteins.

TABLE 1.

Interaction between WISP and Bic-C in yeast two-hybrid assay

| AD | AD-WISP | |

|---|---|---|

| BD | — | — |

| BD-Bic-C | — | + |

AD, activation domain. BD, DNA-binding domain. +, growth on −Trp −Leu −His and −Trp −Leu −His −Ade media. —, no growth on −Trp −Leu −His or −Trp −Leu −His −Ade media.

bicoid poly(A) tail length does not increase in wisp mutant embryos:

Given that the WISP protein is a GLD-2 homolog, we wanted to determine whether it is involved in modulating the length of the poly(A) tail of maternal mRNAs during egg activation. We focused first on bicoid (bcd), whose product is essential for anterior structure formation in Drosophila embryos (Driever and Nusslein-Volhard 1988). Maternal bcd mRNA remains untranslated until it receives an extended poly(A) tail during egg activation (Salles et al. 1994).

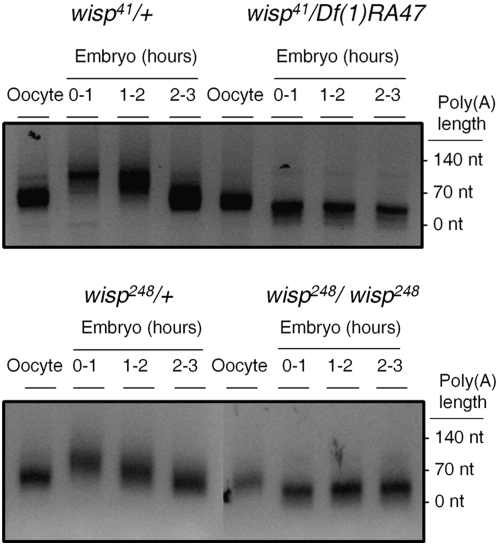

We used a PCR-based PAT assay (Salles and Strickland 1995) to measure the length of the poly(A) tail on bcd mRNA in oocytes and laid (that is, activated) embryos. We obtained these oocytes and embryos from mated “wisp females” that either are homozygous for a wisp allele or carry one wisp mutant allele over a deficiency of the wisp locus, Df(1)RA47. Heterozygous sibling females with one copy of a wisp mutant allele and one copy of a balancer chromosome carrying a wild-type wisp+ allele were used as controls. In embryos from wisp41/+ and wisp248/+ control females, bcd poly(A) tail length, which is ∼70 nt in oocytes, increases in 0- to 1-hr embryos (after activation), reaching a peak length of ∼140 nt (Figure 3). These observations are consistent with previous reports for the magnitude of the change in bcd poly(A) tail length during egg activation (Salles et al. 1994). However, in 0- to1-hr embryos from wisp41/Df(1)RA47 and wisp248/wisp248 females, the poly(A) tail of bcd mRNA does not show this increase in length. Rather, there is a small (∼40 nt) decrease in the length of the bcd poly(A) tail in embryos from wisp females (Figure 3). Thus, WISP protein is required for the extension of the bcd poly(A) tail upon activation. A short poly(A) tail could affect translation of the BCD protein. Although Tadros et al. (2003) reported that BCD is translated in wisp mutants, a shorter poly(A) tail could affect translation efficiency, leading to a reduced level of BCD protein in wisp mutants. Unfortunately, we were unable to quantify BCD protein levels because no suitably specific antibody is available. Two other maternal mRNAs, Toll and torso, that are also polyadenylated upon activation (Salles et al. 1994) similarly fail to acquire extended poly(A) tails in wisp mutants (supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 3.—

Failure of bicoid mRNA polyadenylation in embryos from wisp mothers. Total RNA was extracted from ovarian oocytes or different stages of embryos from females of the indicated genotypes. PAT assays were performed to analyze the length of the bcd poly(A) tail. Tail lengths were estimated on the basis of molecular size markers. bcd poly(A) tail length increased in control embryos after egg activation (left). Polyadenylation of bcd mRNA does not occur in wisp mutant embryos (right). Rather, there is an ∼40-nt decrease in the length of the bcd poly(A) tail. PAT assays were performed on two independent sets of wisp41 and control samples, and one set of wisp248 and control samples.

Cytoplasmic polyadenylation of maternal mRNAs is a conserved mechanism that regulates translation during both oogenesis and early embryo development. Previous studies of GLD-2 family PAPs revealed that GLD-2 plays an important role in the meiosis/mitosis decision in C. elegans (Kadyk and Kimble 1998) and in oocyte maturation in both Xenopus (Barnard et al. 2004) and mice (Nakanishi et al. 2006). However, those studies focused on cytoplasmic polyadenylation events during oogenesis; how cytoplasmic elongation of poly(A) tails is regulated following egg activation remains, in contrast, poorly understood. Mature oocytes contain a remarkable array of maternal mRNAs, representing 20–45% of the genes in the mouse genome and 55% of the genes in Drosophila (Wang et al. 2004; Evsikov et al. 2006; Tadros et al. 2007). The translation of these maternal mRNAs is a hallmark of egg activation, because two-dimensional gel electrophoresis in mice (Xu et al. 1994) and sea urchins (Roux et al. 2006) shows a tremendous spike in new protein synthesis within the egg immediately after fertilization. Initiation of the translation of some mRNAs correlates with an increase in the length of their poly(A) tails (Salles et al. 1994). We find that wisp, which encodes a Drosophila homolog of GLD-2 proteins, is essential for regulating polyadenylation of bicoid, Toll, and torso transcripts upon activation. There might be other maternal mRNAs that are regulated by their poly(A) tail lengths in a wisp-dependent manner during Drosophila egg activation, and it will be interesting to identify these mRNAs in the future.

It will also be interesting to know how the wisp-dependent cytoplasmic polyadenylation machinery is turned on during egg activation. Calcium-signaling pathways are major transducers of the egg activation trigger in many systems (reviewed in Ducibella et al. 2006; Parrington et al. 2007; Horner and Wolfner 2008b), so perhaps cytoplasmic polyadenylation is regulated by a calcium signal. A recent study shows calcium involvement in egg activation in Drosophila (Horner and Wolfner 2008a). In addition, studies (Horner et al. 2006; Takeo et al. 2006) of the sarah (sra) gene, which encodes the Drosophila calcipressin, indicate that proper regulation of the calcium-dependent phosphatase calcineurin by Sra is required for egg activation. Horner et al. (2006) showed that bcd mRNA poly(A) tails do not extend in early embryos from sra mutant mothers. This latter result suggests that the calcium-signaling pathway might be upstream of polyadenylation during Drosophila egg activation. Consistent with the idea that cytoplasmic polyadenylation could be calcium regulated, a study of hippocampal neurons in mouse showed that CaMKII can phosphorylate a regulatory site on CPEB to activate cytoplasmic polyadenylation (Atkins et al. 2004). In a model where calcium is upstream of cytoplasmic polyadenylation upon egg activation, calcium could act upstream of WISP or upstream of other possible targets such as those GLD-2-associated factors in other organisms whose homologs are also found in Drosophila, such as Orb and Bic-C. Since cytoplasmic polyadenylation can be affected by the rate of deadenylation, and deadenylation is also turned on upon activation (Tadros and Lipshitz 2005), the calcium-signaling pathway could also potentially act on targets in the deadenylation pathway, such as Smaug (Semotok et al. 2005), during activation.

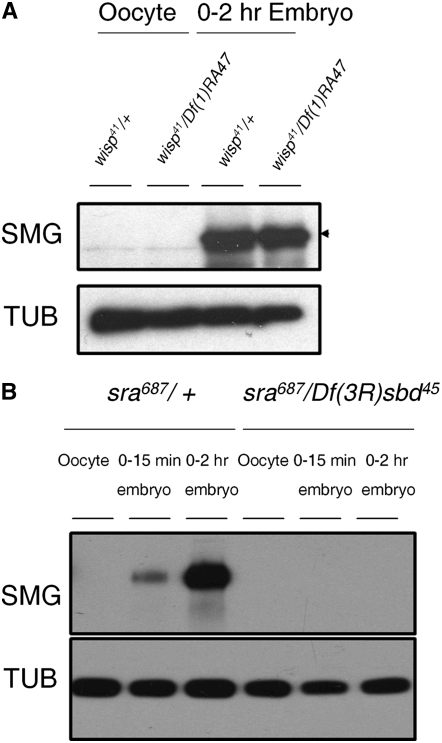

WISP is not required for SMG translation:

In Drosophila, egg activation triggers destabilization of >1600 maternal mRNAs (Tadros et al. 2007). This destabilization has been hypothesized to eliminate maternal transcripts so that zygotic transcription can control later embryogenesis. Smaug (SMG) is the major regulator of this mRNA-destabilizing activity. SMG protein is not present in mature oocytes but is present in embryos (Smibert et al. 1996; Dahanukar et al. 1999). smg mRNA has been reported to be polyadenylated upon egg activation, correlating with, but not absolutely required for, its translation (Tadros et al. 2007). Since WISP is also required for maternal transcript destabilization during egg activation (Tadros et al. 2003), we tested whether SMG protein is translated in embryos in the absence of wisp function. On Western blots, we find that SMG protein is detected in 0- to 2-hr embryos from wisp41 mutant mothers at levels comparable to those in control embryos (Figure 4A). This result indicates that the translation of SMG does not require wisp function. In the future it will be interesting to test if wisp affects the smg transcript's poly(A) tail length.

Figure 4.—

SMG protein is translated in wisp mutant embryos, but not in sra embryos. (A) Total protein extracts of ovarian oocytes (left) and laid 0- to 2-hr embryos (right) from wisp41/Df(1)RA47 or wisp41/+ females were separated by SDS–PAGE, blotted, and probed for Smaug (SMG) and α-tubulin (TUB; loading control). SMG protein is translated normally in laid embryos from wisp mutant females; there is no statistically significant difference between control and mutant embryos in the amount of SMG signal intensity, normalized to TUB signal intensity, in five independent replicates (matched pairs t-test: t-ratio = −0.205, 4 d.f., P = 0.848). (B) Total protein extracts of oocytes, 0- to 15-min embryos and 0- to 2-hr embryos from sra687/+ or sra687/Df(3R)sbd45 females were isolated, blotted, and probed for SMG and α-tubulin (TUB; loading control). SMG protein is not detected in embryos from sra mutant females.

SMG triggers transcript degradation by recruiting the CCR4/POP2/NOT deadenylase complex to specific maternal transcripts to destabilize these mRNAs (Semotok et al. 2005; Tadros et al. 2007). Our finding that SMG is translated in embryos from wisp mutant mothers in conjunction with our previous observation of a small (∼40 nt) decrease in the length of the bcd poly(A) tail in wisp mutant embryos (Figure 3) suggests that the shortening of the bcd poly(A) tail in wisp-deficient embryos might be due to a SMG-dependent increase in deadenylase activity upon activation. Upon egg activation, SMG-dependent deadenylation of the bcd transcript would normally be counteracted by polyadenylation, but this deadenylation could become detectable when polyadenylation is disrupted, as in the wisp mutant. Given that polyadenylation of the bcd transcript is affected in embryos from sra mutants (Horner et al. 2006), we also considered the role of SMG-dependent deadenylation in sra mutants. Horner et al. (2006) showed that bcd mRNA's poly(A) tail is not extended in embryos laid by sra mutant mothers, but in contrast to our observation for wisp mutants, these investigators saw no decrease in the length of the bcd mRNA poly(A) tail in the absence of sra. If the deadenylation of bcd mRNA in wisp mutants is caused by the activation of SMG protein, then the lack of bcd transcript poly(A) decrease in sra embryos might suggest that sra eggs and embryos do not activate SMG translation. Consistent with this prediction, we found that embryos from sra mutant females lack detectable SMG (Figure 4B).

Both WISP and SMG are required for maternal transcript destabilization during egg activation (Tadros et al. 2003). The function of WISP in regulating maternal transcript destabilization cannot be mediated through regulation of SMG translation, because SMG is still translated in wisp-deficient early embryos. Translation of SMG protein upon egg activation is instead known to be activated by the PAN GU (PNG) kinase complex (Tadros et al. 2007), and PNG also plays a role in promoting the polyadenylation of smg mRNA (Tadros et al. 2007) and cyclin B mRNA (Vardy and Orr-Weaver 2007). Future studies are needed to determine whether WISP functions in mRNA destabilization downstream of PNG or instead functions in parallel to the PNG-SMG pathway.

Embryos from wisp mutant females arrest subsequent to the completion of female meiosis but prior to the apposition of female and male pronuclei:

Because wisp mutants fail to carry out two aspects of egg activation [polyadenylation of maternal mRNAs (this study) and maternal mRNA destabilization (Tadros et al. 2003)], we asked whether other aspects of egg activation are affected in wisp mutants. Modifications to the egg coverings are an essential part of egg activation in many species. The vitelline membrane, one of Drosophila's egg coverings, is permeable to small molecules before activation, but after activation vitelline membrane proteins become crosslinked to render the activated egg impermeable to small molecules (Lemosy and Hashimoto 2000; Heifetz et al. 2001). Activated eggs are consequently impermeable to bleach and remain resistant to lysis after a 2-min incubation in 50% bleach, while ∼100% of eggs that have not yet been activated are lysed by this treatment (Mahowald et al. 1983). Zero- to 1-hr eggs laid by either wisp/+ (control) or wisp/wisp females were collected and assayed for bleach resistance. In one representative experiment, 90.5% of wisp41/+ (N = 412) eggs and 92.2% of wisp248/+ (N = 516) eggs were resistant to 50% bleach after a 2-min incubation, while 60.7% of the eggs (N = 384) laid by wisp41/wisp41 (a presumptive null mutation) females and 68.1% of the eggs (N = 426) laid by wisp248/wisp248 females were resistant to bleach, suggesting that vitelline membrane crosslinking occurs in wisp mutants, but might be incomplete or delayed relative to wild type (P < 0.0001). While the exact percentage values vary among other repetitions of this experiment, the difference between controls and wisp mutants remains in the same direction and always statistically significant.

Another aspect of egg activation is the resumption and completion of female meiosis. Brent et al. (2000) reported that embryos laid by wisp12-3147, wisp11-600, and wisp14-1299 females arrest after an abnormal meiosis. Since wisp12-3147 is a missense (or double missense) mutation and the molecular lesions in the other two alleles tested by Brent et al. (2000) are unknown, we were uncertain if they reflect the null phenotype. We therefore chose to analyze two other alleles, wisp41 and wisp248, because the wisp41 allele has a nonsense mutation that removes the majority of the protein, including the entire conserved PAP domain, and thus is likely to be the strongest allele available. We further analyzed the progression of cell cycle phenotype due to wisp41 and wisp248 and determined that both meet the genetic definition of null alleles (Table 2). Both wisp41 and wisp248 females are viable and capable of laying eggs, but these eggs never hatch. We examined the phenotypes of these arrested eggs by using immunofluorescence microscopy. Control and wisp females were mated to wild-type males, and the resultant eggs were collected. They were then fixed and stained with an antibody against α-tubulin to visualize the spindle and with propidium iodide to reveal the chromosomes. Eggs from hemizygous [wisp41/Df(1)RA47 or wisp248/Df(1)RA47] females show the same phenotype as those from homozygous (wisp41/wisp41 or wisp248/wisp248) females. Since the wisp41 allele has a nonsense mutation that removes the majority of the protein, including the entire conserved PAP domain, and meets the genetic definition of a null, we focused further phenotypic analysis on this allele.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of developmental stages of 0- to 2-hr-old embryos

| Genotypes | Meiosis | Mitosis | Arrested |

|---|---|---|---|

| wisp41/FM6 | 2/39 | 37/39 | 0/39 |

| wisp41/wisp41 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 20/20 |

| wisp41/Df(1)RA47 | 1/24 | 0/24 | 23/24 |

| wisp248/FM6 | 3/33 | 30/33 | 0/33 |

| wisp248/wisp248 | 0/31 | 0/31 | 31/31 |

| wisp248/Df(1)RA47 | 0/27 | 0/27 | 27/27 |

Embryos collected from females of the indicated genotype were fixed and stained with propidium iodide and anti-α-tubulin antibody. Stages were determined on the basis of spindle and chromosome configurations.

In wild-type embryos, female meiosis completes upon egg activation and four haploid meiotic products form (Foe et al. 1993). If the egg is fertilized, the sperm nucleus remodels (in part by exchanging protamines for histones) and becomes the male pronucleus. One of the four female meiotic products migrates toward, and apposes with, the male pronucleus, and then the two apposed pronuclei together enter the first mitotic division. The other three female meiotic products stay at the cortex of the embryo and form a polar body rosette. We examined whether or not wisp eggs can be fertilized, and whether meiosis and pronuclear behaviors are normal. Asters can be observed using α-tubulin antibody and the sperm tail can be observed using an antibody against the sperm tail in embryos from wisp41 mutant females (supplemental Figure 2) as was also stated for wisp12-3147 mutants (Brent et al. 2000). Thus, the lack of development of wisp embryos is not due to lack of fertilization.

As expected, the majority of 0- to 1-hr fertilized eggs (embryos) laid by wisp41/+ heterozygous females undergo embryonic mitotic divisions (Figure 5A). In contrast, no embryos from wisp homozygous mutant females enter a normal zygotic mitosis. Instead, they are arrested at an aberrant metaphase-like stage with very few (usually five or fewer) spindles (Figure 5B). The chromosomes associated with the spindle structures are condensed and appear to have entered a division cycle, since their chromatin can be stained by an antibody against the mitosis marker phospho-H3 (data not shown). The spindles in these arrested embryos are clearly different from mitotic spindles, since in general they are not associated with microtubule-organizing centers (MTOC). However, one spindle deep inside the embryo, with two aster structures, can be observed in some of these fertilized eggs (Figure 5B inset). Centrosomes in Drosophila embryos are paternally derived (Foe et al. 1993), suggesting that the centrosome-containing spindle in wisp embryos is associated with the male pronucleus while the other spindles are associated with the four female meiotic products. The arrest phenotype that we see for wisp41 is like that described for wisp12-3147 (Brent et al. 2000), suggesting that the point mutations that we mapped in the latter allele completely disrupt wisp function.

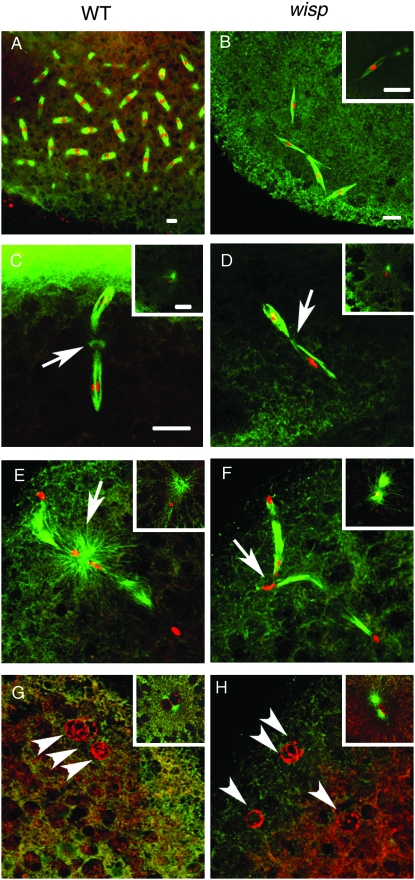

Figure 5.—

Fertilized eggs from wisp mutant females arrest subsequent to the completion of female meiosis. Embryos derived from wisp41/Df(1)RA47 or wisp41/+ control females were fixed and stained with propidium iodide to visualize DNA (red) and with anti-α-tubulin antibody to visualize microtubules (green). Insets show the male nucleus in each embryo. A control 0- to 1-hr-embryo undergoes mitotic divisions (A) while a 0- to 1-hr embryo from a wisp41 mutant female is arrested with multiple spindle structures (B). Five- to 15-min embryos were used to observe female meiosis (C–H). Compared to control embryos' metaphase II (C) and telophase II (E), metaphase II (D) and telophase II (F) in wisp41 mutant embryos have reduced green staining of the acentriolar MTOC between the two linked meiotic spindles (arrows). Female meiosis in control embryos results in four products, three near the surface of the embryo (G, arrowheads) and one apposing the male nucleus (G inset). All four female meiotic products are found near the surface of the wisp41 mutant embryo (H, arrowheads); none apposed to the male pronucleus (H inset). Bar, 10 μm. D–H are at the same magnification as C.

Given that wisp embryos arrest before embryonic mitosis, we examined whether or not WISP function is essential for fertilized eggs (embryos) to complete female meiosis. We stained 5- to 15-min embryos from either wisp41/+ heterozygous control females or wisp41/Df(1)RA47 mutant females and checked the progression of female meiosis after these females were mated to wild-type males. All stages of female meiosis are observed in wisp mutants (Table 3), although one aspect of meiosis appears abnormal. In controls, the two meiosis II spindles are tandemly linked, and bright α-tubulin staining can be seen in an acentriolar MTOC between the two spindles in metaphase II (Figure 5C) and telophase II (Figure 5E). However in wisp mutants, the staining of the acentriolar MTOC between the two meiosis II spindles is greatly diminished (Figure 5 D and F).

TABLE 3.

Meiotic progression in 5- to 15-min-old embryos

| Genotype | Embryos scored | Metaphase I (%) | Anaphase I (%) | Metaphase II (%) | Anaphase II (%) | Telophase II (%) | Pronulei (%) | Mitosis (%) | Arrested (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wisp41/+ | 128 | 0 (0) | 5 (3.9) | 16 (12.5) | 9 (7.0) | 26 (20.3) | 23 (10.2) | 49 (38.3) | 0 (0) |

| wisp41/Df(1)RA47 | 103 | 1 (1.0) | 5 (4.9) | 11 (12.1) | 4 (3.9) | 16 (15.5) | 16 (15.5) | 0 (0) | 50 (48.5) |

Embryos were collected 10 min after deposition by females of the indicated genotype, fixed for 5 min, and stained with propidium iodide and anti-α-tubulin antibody to score meiotic and mitotic figures. Stages were determined on the basis of spindle and chromosome configurations.

Although meiosis can complete in wisp mutants, we see abnormalities in pronuclear behavior thereafter. In embryos from wisp mutant females, the paternal chromosomes decondense to form a male pronucleus (insets of Figure 5, D, F, and H), as in control embryos (insets of Figure 5, C, E, and G). The aster duplicates in the embryos from wisp mutant females (inset Figure 5F). However, none of the female meiotic products migrates toward the male pronucleus, and there is thus no pronuclear apposition (Figure 5H). Several considerations suggest that the effects of wisp mutants on pronuclear migration might reflect wisp-mediated control of the synthesis or levels of a microtubule-associated protein or a regulator of this association. In embryos from wisp mutant females, the two centrosome-associated proteins γ-tubulin and CP190 are reduced in the centrosomes compared to wild type, while CP60 is not detected (Brent et al. 2000). Failure of pronuclear migration as observed in wisp-deficient embryos also occurs in embryos from asp or KLP3A mutant females, which lack certain microtubule-associated proteins (Williams et al. 1997; Riparbelli et al. 2002). Moreover, defective acentriolar MTOC of meiosis II, reduced sperm aster growth, and failure of pronuclear migration, all seen in wisp-deficient embryos, have also been reported in mutant embryos lacking POLO, which regulates the organization of microtubule-associated structures (Riparbelli et al. 2000).

Wild-type Drosophila eggs can activate without fertilization. Such unfertilized eggs can complete female meiosis but do not develop further (Doane 1960; Foe et al. 1993). The four haploid nuclei derived from female meiosis retreat to the egg surface and fuse to form a polar body rosette structure; the chromosomes in the rosette are condensed in a mitotic-like arrest (Page and Orr-Weaver 1997). We examined the four maternally derived nuclei in unfertilized eggs from wisp41/Df(1)RA47 females. In control eggs, a polar body rosette structure forms normally (Figure 6, A and C). However, the four maternally derived nuclei in unfertilized wisp-deficient eggs become associated with spindles that resemble meiotic spindles (Figure 6B). In some cases, the four haploid nuclei fuse to associate with an irregular-sized spindle, but still no rosette-like structure can be observed (Figure 6D). These findings suggest that the arrest of these wisp mutant eggs is different from the arrest of the polar body nuclei in wild-type unfertilized eggs.

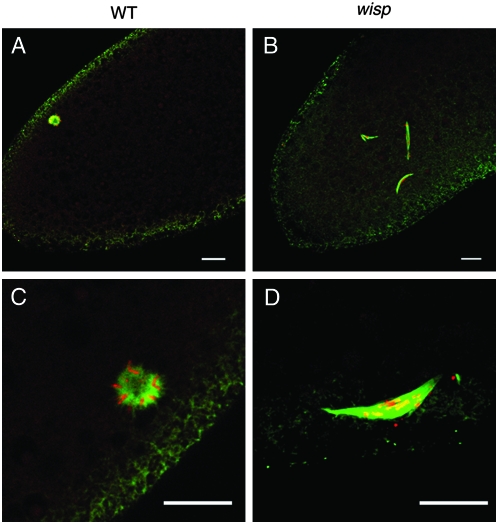

Figure 6.—

Female meiotic products in unfertilized wisp eggs. Laid unfertilized eggs from wisp41/+ control (A and C) or wisp41/Df(1)RA47 (B and D) mothers were fixed and stained with propidium iodide to visualize DNA (red) and with anti-α-tubulin antibody to visualize microtubules (green). Ninety-three percent (n = 56) of control eggs formed the polar body rosette. In 100% (n = 57) of the eggs from mutant mothers, the female meiotic products associate with anastral spindles (B). In ∼45% of these eggs, apposition of multiple female meiotic products can be observed, but no polar rosette is formed (D). Bar, 10 μm.

Levels of some active (phospho-) MAPKs are decreased in wisp mutant oocytes:

Because we observed WISP protein both in ovaries and in embryos after egg activation, and because wisp mutant oocytes have a defect during the meiosis I arrest prior to egg activation (Brent et al. 2000), we considered the possibility that WISP might have functions in mature oocytes immediately before egg activation. In Drosophila oocytes, levels of active (that is, phosphorylated) MAPKs are high, but upon egg activation (independent of fertilization), the amounts of the active forms of the MAPKs decrease although the total amounts of the MAPK proteins do not change (Sackton et al. 2007). Three classes of MAPK ]extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK), Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38] are present in Drosophila, as in other organisms. The change in MAPK activity between mature oocytes and activated eggs suggests that MAPK-signaling cascades have a necessary function in oocytes and lack of MAPK signaling could be important upon egg activation.

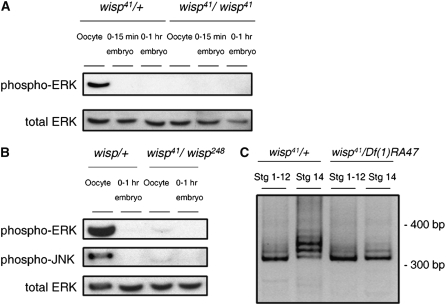

To determine if wisp affects MAPK activity at or before egg activation, we examined the amount of phospho-MAPKs in wisp mutant oocytes and embryos. In wisp41/+ controls (Figure 7A, left), the level of phospho-ERK is high in mature (stage 14) oocytes and decreases upon egg activation as seen previously in wild type (Sackton et al. 2007). In contrast, the level of phospho-ERK in wisp mutant mature oocytes is much lower than in control mature oocytes (Figure 7A, right). Similarly, stage 14 wisp oocytes also contain an unusually low level of phospho-JNK relative to controls (Figure 7B), although their levels of phospho-p38 are normal (data not shown). Upon egg activation, the levels of phospho-ERK and phospho-JNK in wisp embryos are very low or undetectable, as in wild-type embryos (Figures 7, A and B). These results suggest that wisp plays a role in regulating MAP kinase activity during oogenesis.

Figure 7.—

Levels of phospho-ERK and phospho-JNK and lengths of dmos poly(A) tails are decreased in wisp mutant oocytes. (A) Western blot analysis was performed on total protein extracts of mature (stage 14) ovarian oocytes, 0- to 15-min or 0- to 1-hr embryos from wisp41/wisp41 or wisp41/+ females. Anti-ERK was used to detect total ERK protein while anti-phospho-ERK was used to detect the active form of ERK. (B) Anti-phospho-JNK was used to detect the active form of JNK in total protein extracts of mature oocytes or 0- to 1-hr embryos from wisp41/wisp248 or heterozygous control females. Anti-ERK was used here as a loading control. (C) Stages 1–12 and stage 14 oocytes were hand dissected from wisp41/+ control and wisp41/Df(1)RA47 mutant females. PAT assays were performed to examine the poly(A) tail length of dmos mRNA. PAT assay products were separated by DNA PAGE. Molecular size markers are shown on the right. In the controls (two lanes on left), the length of the dmos mRNA poly(A) tail is ∼40 nt longer in stage 14 oocytes than in stages 1–12 (two lanes on left), indicating extension of the dmos mRNA poly(A) tails during oocyte maturation. In contrast, this increase is not seen in wisp mutant oocytes (two lanes on right).

Because total ERK protein levels are normal in wisp mature oocytes, WISP regulates the activation of this kinase, not its translation. WISP could regulate translation of an upstream activating kinase or kinases in oocytes, so that these kinase(s) in turn can regulate the phosphorylation and activity of ERK and JNK. Studies in Xenopus have shown that CPEB-mediated polyadenylation regulates the translation of mos mRNA during oocyte maturation (Sheets et al. 1995; Stebbins-Boaz et al. 1996) and that MOS phosphorylates MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK), a kinase that then phosphorylates MAPKs in mature oocytes (Maller et al. 2002). Decreased levels of phospho-ERK and phospho-MEK were observed in oocytes from dmos germline clones in Drosophila (Ivanovska et al. 2004). MOS has also been shown to activate JNK in Xenopus eggs and embryos (Bagowski et al. 2001; Mood et al. 2004).

The decreased levels of phospho-ERK and phospho-JNK in wisp-deficient Drosophila mature oocytes could be attributable to upstream regulation by DMOS. We explored the possibility that dmos transcripts' poly(A) tails could be extended during oocyte maturation, as is the case for Xenopus mos, and for Drosophila cortex and cyclin B transcripts (Benoit et al. 2005; Pesin and Orr-Weaver 2007), and that wisp could mediate this, by analogy to the requirement for xGLD-2 for CPEB-mediated polyadenylation during Xenopus oogenesis (Barnard et al. 2004). We used PAT assays to examine dmos mRNA's poly(A) tail length in immature (stages 1–12) and mature (stage 14) oocytes from control females or wisp mutant females. In the controls (Figure 7C, two lanes on left), dmos transcripts have shorter poly(A) tails in stage 1–12 (immature) oocytes; their poly(A) tails are longer by ∼40 nt in stage 14 (mature) oocytes. Thus, dmos mRNA poly(A) tails lengthen during oocyte maturation in Drosophila, as in Xenopus. In contrast to the situation in controls, the length of the poly(A) tails of dmos mRNA in mature oocytes of wisp41 mutant females is not significantly different from that in immature oocytes of these females (Figure 7C, two lanes on right). Therefore, wisp function is needed for poly(A) tail extension on dmos mRNA during oocyte maturation.

The shorter poly(A) tail in mature wisp oocytes could lead to a failure or inefficiency of dmos translation that would in turn explain the decreased levels of phospho-ERK and phospho-JNK. We unfortunately are unable to examine DMOS protein levels in Drosophila because there is no suitably specific antibody available. However, we find that our preliminary data indicate that phospho-MEK levels are low in wisp mutant mature oocytes (data not shown), supporting the hypothesis that MAPK phosphorylation is regulated through the upstream kinases MEK and DMOS during Drosophila oocyte maturation and that wisp controls this by controlling the polyadenylation of dmos mRNA (at least) during egg maturation.

Although levels of phospho-ERK and phospho-JNK are low or undetectable in wisp mutant mature oocytes, meiosis can still complete upon activation of those eggs. This result is consistent with a previous report that oocytes from dmos mutant germline clones have decreased levels of phospho-ERK yet they can complete meiosis (Ivanovska et al. 2004). Although MAPK activity downstream of DMOS is not necessary for completion of meiosis in Drosophila, the regulation of MAPKs or other genes by WISP may be important for other aspects of late oocyte development or for making the oocyte competent to activate.

Conclusions:

We have shown that the wisp gene encodes a Drosophila member of the GLD-2 cytoplasmic PAP family and that the product of this gene is necessary for several aspects of egg activation and oogenesis. WISP is required for the polyadenylation of bicoid, Toll, and torso mRNAs upon egg activation. However, translation of SMG, which has been previously reported to correlate with but not depend on polyadenylation of smg mRNA upon activation (Tadros et al. 2007), is WISP independent. wisp maternal-effect mutations lead to very early developmental arrest prior to embryonic mitosis. Eggs lacking maternal WISP function are capable of completing female meiosis to form decondensed female meiotic products. Although the sperm nucleus appears capable of remodeling and forming a male pronucleus in the absence of WISP function, the sperm asters fail to grow and pronuclear migration does not occur. All the nuclei condense their chromosomes and become associated with a spindle structure, but then arrest at this point. These data are consistent with wisp's being essential for some aspect of the tubulin cytoskeleton in oocytes and embryos. WISP also has functions during oogenesis because levels of active (phospho-) MAPKs are severely reduced in wisp oocytes and dmos mRNA poly(A) tails fail to extend in wisp oocytes during oocyte maturation.

Given its molecular identity, it is likely that WISP affects these aspects of egg activation and oogenesis by a single mechanism: determination of the poly(A) tail length of certain maternal mRNAs. It is likely that there are more mRNA targets of WISP in addition to the ones identified in this study. Future identification of these mRNA targets whose poly(A) tail increase during oogenesis or upon egg activation is wisp dependent will help to elucidate whether and how products of these genes play roles in oogenesis and egg activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Liu, M. Goldberg, W. Tadros, and anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions on experiments and for comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to W. Tadros and H. Lipshitz for wisp41/FM6, wisp248/FM6, and wisp249/FM6 stocks and for anti-SMG. We thank T. Karr for the anti-sperm tail antibody. We appreciate the excellent technical assistance of K. Becetti in the yeast two-hybrid tests. Our studies were supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM44659 to M.F.W. For part of this work V.L.H. was supported by a Dissertation Fellowship from the American Association of University Women.

References

- Atkins, C. M., N. Nozaki, Y. Shigeri and T. R. Soderling, 2004. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein-dependent protein synthesis is regulated by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J. Neurosci. 24 5193–5201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagowski, C. P., W. Xiong and J. E. Ferrell, Jr., 2001. c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation in Xenopus laevis eggs and embryos. A possible non-genomic role for the JNK signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 276 1459–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkoff, A. F., K. S. Dickson, N. K. Gray and M. Wickens, 2000. Translational control of cyclin B1 mRNA during meiotic maturation: coordinated repression and cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Dev. Biol. 220 97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, D. C., K. Ryan, J. L. Manley and J. D. Richter, 2004. Symplekin and xGLD-2 are required for CPEB-mediated cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Cell 119 641–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, B., G. Mitou, A. Chartier, C. Temme, S. Zaessinger et al., 2005. An essential cytoplasmic function for the nuclear poly(A) binding protein, PABP2, in poly(A) tail length control and early development in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 9 511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell, R. E., and A. P. Mahowald, 1985. tudor, a gene required for assembly of the germ plasm in Drosophila melanogaster. Cell 43 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent, A. E., A. MacQueen and T. Hazelrigg, 2000. The Drosophila wispy gene is required for RNA localization and other microtubule-based events of meiosis and early embryogenesis. Genetics 154 1649–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, J., and G. Struhl, 1989. Localized surface activity of torso, a receptor tyrosine kinase, specifies terminal body pattern in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 3 2025–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagnetti, S., and A. Ephrussi, 2003. Orb and a long poly(A) tail are required for efficient oskar translation at the posterior pole of the Drosophila oocyte. Development 130 835–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chicoine, J., P. Benoit, C. Gamberi, M. Paliouras, M. Simonelig et al., 2007. Bicaudal-C recruits CCR4-NOT deadenylase to target mRNAs and regulates oogenesis, cytoskeletal organization, and its own expression. Dev. Cell 13 691–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahanukar, A., J. A. Walker and R. P. Wharton, 1999. Smaug, a novel RNA-binding protein that operates a translational switch in Drosophila. Mol. Cell 4 209–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, K. S., A. Bilger, S. Ballantyne and M. P. Wickens, 1999. The cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor in Xenopus laevis oocytes is a cytoplasmic factor involved in regulated polyadenylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 5707–5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, K. S., S. R. Thompson, N. K. Gray and M. Wickens, 2001. Poly(A) polymerase and the regulation of cytoplasmic polyadenylation. J. Biol. Chem. 276 41810–41816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doane, W. W., 1960. Completion of meiosis in uninseminated eggs of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 132 677–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driever, W., and C. Nusslein-Volhard, 1988. A gradient of bicoid protein in Drosophila embryos. Cell 54 83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducibella, T., R. M. Schultz and J.-P. Ozil, 2006. Role of calcium signals in early development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 17 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evsikov, A. V., J. H. Graber, J. M. Brockman, A. Hampl, A. E. Holbrook et al., 2006. Cracking the egg: molecular dynamics and evolutionary aspects of the transition from the fully grown oocyte to embryo. Genes Dev. 20 2713–2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiumera, A. C., B. L. Dumont and A. G. Clark, 2005. Sperm competitive ability in Drosophila melanogaster associated with variation in male reproductive proteins. Genetics 169 243–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foe, V. E., G. M. Odell and B. A. Edgar, 1993. Mitosis and morphogenesis in the Drosophila embryo: point and counterpoint, pp. 149–300 in The Development of Drosophila melanogaster, edited by M. Bate and A. Martinez Arias. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY.

- Hake, L. E., and J. D. Richter, 1994. CPEB is a specificity factor that mediates cytoplasmic polyadenylation during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Cell 79 617–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, C., K. L. Hudson and K. V. Anderson, 1988. The Toll gene of Drosophila, required for dorsal-ventral embryonic polarity, appears to encode a transmembrane protein. Cell 52 269–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heifetz, Y., J. Yu and M. F. Wolfner, 2001. Ovulation triggers activation of Drosophila oocytes. Dev. Biol. 234 416–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner, V. L., and M. F. Wolfner, 2008. a Mechanical stimulation by osmotic and hydrostatic pressure activates Drosophila oocytes in vitro in a calcium-dependent manner. Dev. Biol. 136 100–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner, V. L., and M. F. Wolfner, 2008. b Transitioning from egg to embryo: triggers and mechanisms of egg activation. Dev. Dyn. 237 527–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner, V. L., A. Czank, J. K. Jang, N. Singh, B. C. Williams et al., 2006. The Drosophila calcipressin sarah is required for several aspects of egg activation. Curr. Biol. 16 1441–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovska, I., E. Lee, K. M. Kwan, D. D. Fenger and T. L. Orr-Weaver, 2004. The Drosophila MOS ortholog is not essential for meiosis. Curr. Biol. 14 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadyk, L. C., and J. Kimble, 1998. Genetic regulation of entry into meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 125 1803–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, J. E., and M. Wickens, 2007. A family of poly(U) polymerases. RNA 13 860–867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, J. E., L. Wang, S. Ballantyne, J. Kimble and M. Wickens, 2004. Mammalian GLD-2 homologs are poly(A) polymerases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 4407–4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz, V., J. S. Chang, J. I. Horabin, D. Bopp and P. Schedl, 1994. The Drosophila orb RNA-binding protein is required for the formation of the egg chamber and establishment of polarity. Genes Dev. 8 598–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMosy, E. K., and C. Hashimoto, 2000. The nudel protease of Drosophila is required for eggshell biogenesis in addition to embryonic patterning. Dev. Biol. 217 352–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahone, M., E. E. Saffman and P. F. Lasko, 1995. Localized Bicaudal-C RNA encodes a protein containing a KH domain, the RNA binding motif of FMR1. EMBO J. 14 2043–2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahowald, A. P., T. J. Goralski and J. H. Caulton, 1983. In vitro activation of Drosophila eggs. Dev. Biol. 98 437–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maller, J. L., M. S. Schwab, S. D. Gross, F. E. Taieb, B. T. Roberts et al., 2002. The mechanism of CSF arrest in vertebrate oocytes. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 187 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, R., and J. D. Richter, 2001. Translational control by CPEB: a means to the end. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2 521–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, R., K. G. Murthy, K. Ryan, J. L. Manley and J. D. Richter, 2000. Phosphorylation of CPEB by Eg2 mediates the recruitment of CPSF into an active cytoplasmic polyadenylation complex. Mol. Cell 6 1253–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mood, K., Y. S. Bong, H. S. Lee, A. Ishimura and I. O. Daar, 2004. Contribution of JNK, Mek, Mos and PI-3K signaling to GVBD in Xenopus oocytes. Cell. Signal. 16 631–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi, T., H. Kubota, N. Ishibashi, S. Kumagai, H. Watanabe et al., 2006. Possible role of mouse poly(A) polymerase mGLD-2 during oocyte maturation. Dev. Biol. 289 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, A. W., and T. L. Orr-Weaver, 1997. Activation of the meiotic divisions in Drosophila oocytes. Dev. Biol. 183 195–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrington, J., L. C. Davis, A. Galione and G. Wessel, 2007. Flipping the switch: how a sperm activates the egg at fertilization. Dev. Dyn. 236 2027–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesin, J. A., and T. L. Orr-Weaver, 2007. Developmental role and regulation of cortex, a meiosis-specific anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome activator. PLoS Genet. 3 e202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi Ram, K., S. Ji and M. F. Wolfner, 2005. Fates and targets of male accessory gland proteins in mated female Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 35 1059–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riparbelli, M. G., G. Callaini and D. M. Glover, 2000. Failure of pronuclear migration and repeated divisions of polar body nuclei associated with MTOC defects in polo eggs of Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 113 3341–3350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riparbelli, M. G., G. Callaini, D. M. Glover and C. Avides Mdo, 2002. A requirement for the Abnormal Spindle protein to organise microtubules of the central spindle for cytokinesis in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 115 913–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux, M. M., I. K. Townley, M. Raisch, A. Reade, C. Bradham et al., 2006. A functional genomic and proteomic perspective of sea urchin calcium signaling and egg activation. Dev. Biol. 300 416–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, A. B., P. Sarnow and M. W. Hentze, 1997. Starting at the beginning, middle, and end: translation initiation in eukaryotes. Cell 89 831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackton, K. L., N. A. Buehner and M. F. Wolfner, 2007. Modulation of MAPK activities during egg activation in Drosophila. Fly 1 222–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffman, E. E., S. Styhler, K. Rother, W. Li, S. Richard et al., 1998. Premature translation of oskar in oocytes lacking the RNA-binding protein bicaudal-C. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 4855–4862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salles, F. J., and S. Strickland, 1995. Rapid and sensitive analysis of mRNA polyadenylation states by PCR. PCR Methods Appl. 4 317–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salles, F. J., M. E. Lieberfarb, C. Wreden, J. P. Gergen and S. Strickland, 1994. Coordinate initiation of Drosophila development by regulated polyadenylation of maternal messenger RNAs. Science 266 1996–1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semotok, J. L., R. L. Cooperstock, B. D. Pinder, H. K. Vari, H. D. Lipshitz et al., 2005. Smaug recruits the CCR4/POP2/NOT deadenylase complex to trigger maternal transcript localization in the early Drosophila embryo. Curr. Biol. 15 284–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets, M. D., M. Wu and M. Wickens, 1995. Polyadenylation of c-mos mRNA as a control point in Xenopus meiotic maturation. Nature 374 511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smibert, C. A., J. E. Wilson, K. Kerr and P. M. Macdonald, 1996. smaug protein represses translation of unlocalized nanos mRNA in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 10 2600–2609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins-Boaz, B., L. E. Hake and J. D. Richter, 1996. CPEB controls the cytoplasmic polyadenylation of cyclin, Cdk2 and c-mos mRNAs and is necessary for oocyte maturation in Xenopus. EMBO J. 15 2582–2592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros, W., and H. D. Lipshitz, 2005. Setting the stage for development: mRNA translation and stability during oocyte maturation and egg activation in Drosophila. Dev. Dyn. 232 593–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros, W., S. A. Houston, A. Bashirullah, R. L. Cooperstock, J. L. Semotok et al., 2003. Regulation of maternal transcript destabilization during egg activation in Drosophila. Genetics 164 989–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros, W., A. L. Goldman, T. Babak, F. Menzies, L. Vardy et al., 2007. SMAUG is a major regulator of maternal mRNA destabilization in Drosophila and its translation is activated by the PAN GU kinase. Dev. Cell 12 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeo, S., M. Tsuda, S. Akahori, T. Matsuo and T. Aigaki, 2006. The calcineurin regulator sra plays an essential role in female meiosis in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 16 1435–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardy, L., and T. L. Orr-Weaver, 2007. The Drosophila PNG kinase complex regulates the translation of cyclin B. Dev. Cell 12 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L., C. R. Eckmann, L. C. Kadyk, M. Wickens and J. Kimble, 2002. A regulatory cytoplasmic poly(A) polymerase in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 419 312–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. T., K. Piotrowska, M. A. Ciemerych, L. Milenkovic, M. P. Scott et al., 2004. A genome-wide study of gene activity reveals developmental signaling pathways in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev. Cell 6 133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B. C., A. F. Dernburg, J. Puro, S. Nokkala and M. L. Goldberg, 1997. The Drosophila kinesin-like protein KLP3A is required for proper behavior of male and female pronuclei at fertilization. Development 124 2365–2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z., G. S. Kopf and R. M. Schultz, 1994. Involvement of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-mediated Ca2+ release in early and late events of mouse egg activation. Development 120 1851–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]