Abstract

Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) is expressed when infected males are crossed with either uninfected females or females infected with Wolbachia of different CI specificity. In diploid insects, CI results in embryonic mortality, apparently due to the the loss of the paternal set of chromosomes, usually during the first mitotic division. The molecular basis of CI has not been determined yet; however, several lines of evidence suggest that Wolbachia exhibits two distinct sex-dependent functions: in males, Wolbachia somehow “imprints” the paternal chromosomes during spermatogenesis (mod function), whereas in females, the presence of the same Wolbachia strain(s) is able to restore embryonic viability (resc function). On the basis of the ability of Wolbachia to induce the modification and/or rescue functions in a given host, each bacterial strain can be classified as belonging in one of the four following categories: mod+ resc+, mod− resc+, mod− resc−, and mod+ resc−. A so-called “suicide” mod+ resc− strain has not been found in nature yet. Here, a combination of embryonic cytoplasmic injections and introgression experiments was used to transfer nine evolutionary, distantly related Wolbachia strains (wYak, wTei, wSan, wRi, wMel, wHa, wAu, wNo, and wMa) into the same host background, that of Drosophila simulans (STCP strain), a highly permissive host for CI expression. We initially characterized the modification and rescue properties of the Wolbachia strains wYak, wTei, and wSan, naturally present in the yakuba complex, upon their transfer into D. simulans. Confocal microscopy and multilocus sequencing typing (MLST) analysis were also employed for the evaluation of the CI properties. We also tested the compatibility relationships of wYak, wTei, and wSan with all other Wolbachia infections. So far, the cytoplasmic incompatibility properties of different Wolbachia variants are explained assuming a single pair of modification and rescue factors specific to each variant. This study shows that a given Wolbachia variant can possess multiple rescue determinants corresponding to different CI systems. In addition, our results: (a) suggest that wTei appears to behave in D. simulans as a suicide mod+ resc− strain, (b) unravel unique CI properties, and (c) provide a framework to understand the diversity and the evolution of new CI-compatibility types.

WOLBACHIA is a group of maternally transmitted intracellular bacteria that infect numerous arthropod as well as filarial nematode species (Werren 1997; Bandi et al. 1998; Stouthamer et al. 1999). In arthropod hosts, Wolbachia mainly reside in ovaries and testes. In many cases, they manipulate host reproduction to ensure their own transmission by inducing feminization (Rigaud 1997), thelytokous parthenogenesis (Huigens and Stouthamer 2003), male killing (Hurst et al. 2003) and, most commonly, cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) (Bourtzis et al. 2003). In diploid species, CI is expressed as embryonic lethality of the progeny of a male infected by one (or more) Wolbachia strain(s) and a female that either is uninfected or carries a different Wolbachia strain (Bourtzis et al. 2003).

The molecular mechanism of CI has not yet been elucidated; currently available data, however, suggest that Wolbachia modifies nuclear components of the sperm during spermatogenesis (Presgraves 2000). This is called the modification action of Wolbachia (mod function) (Werren 1997). This modification prevents the paternal set of chromosomes from entering the anaphase of the first mitotic division, resulting in failure of zygote development unless the same Wolbachia strain(s) is/are present in the egg and exert(s) the respective rescue function(s) (resc, for rescue) (Lassy and Karr 1996; Callaini et al. 1997; Werren 1997; Tram and Sullivan 2002; Ferree and Sullivan 2006). It has been suggested that mod and resc interact in a lock-and-key manner, with a direct inhibition of the mod factor (the lock) by the resc factor (the key) (Poinsot et al. 2003); recent observations have supported this model (Ferree and Sullivan, 2006). On the basis of this model, any Wolbachia/host association can be classified as belonging to one of the four following phenotypic categories: mod+ resc+, mod− resc+, mod− resc−, and mod+ resc−, depending on their modification and/or rescue properties (Poinsot et al. 2003). The phenotypes mod+ resc+, mod− resc+, and mod− resc− have been observed in many different Wolbachia/host associations (Werren 1997; McGraw and O'Neill 1999; Charlat et al. 2001, 2002a; Weeks et al. 2002; Bourtzis et al. 2003). The mod+ resc− phenotype describes Wolbachia strains, which are able to induce CI without being capable of rescuing their own modification. Such strains have not been found yet, but theory does not preclude their maintenance in natural populations (Charlat et al. 2001, 2002a).

Wolbachia infections and their association with Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility phenomena have extensively been studied in Drosophila species. D. melanogaster seems to harbor a group of very closely related Wolbachia strains, known as wMel, that induce variable levels of CI depending on the bacterial and host genotypes and male age (Hoffmann 1988; Boyle et al. 1993; Hoffmann et al. 1994; Holden et al. 1993; Bourtzis et al. 1994, 1996; Solignac et al. 1994; McGraw et al. 2001; Reynolds and Hoffmann 2002; Weeks et al. 2002; Merçot and Charlat 2004; Riegler et al. 2005). D. simulans harbors at least five phylogenetically and phenotypically distinct strains: wRi, wHa, wNo, wMa, and wAu (Merçot and Charlat 2004). The wRi, wHa, and wNo strains are able to express both the modification and the rescue function in their natural host and are all bidirectionally incompatible (Hoffmann et al. 1986; O'neill and Karr 1990; Merçot et al. 1995). The wMa strain is considered a mod− resc+ strain, unable to express the modification function, but being able to fully rescue the modification of the wNo strain (Rousset and Solignac 1995; Merçot and Poinsot 1998a; Charlat et al. 2003). The wAu strain is considered a mod− resc− strain (Hoffmann et al. 1996; Poinsot et al. 1998; Merçot and Poinsot 1998b; James and Ballard 2000; Reynolds and Hoffmann 2002; Charlat et al. 2003). Two Wolbachia strains have been described in D. sechellia, wSh and wSn; both are considered mod+ resc+ and they are bidirectionally incompatible (Rousset and Solignac 1995; Charlat et al. 2002b). In D. mauritiana, only Wolbachia strain wMau has been described, which corresponds to wMa following introgression of the genome of D. mauritiana in the siIII cytoplasm of D. simulans (Rousset and Solignac 1995). The CI properties of wMau appear to be identical to those of wMa from D. simulans: wMau has been shown to be incapable of expressing a modification function but it can fully rescue the modification of the wNo strain, thus expressing a mod− resc+ phenotype (Giordano et al. 1995; Rousset and Solignac 1995; Bourtzis et al. 1998; James and Ballard 2000; James et al. 2002). The Wolbachia strains wYak, wTei, and wSan have been reported to infect D. yakuba, D. teissieri, and D. santomea, respectively (Lachaise et al. 2000; Zabalou et al. 2004a). These strains were shown to be unable to express a mod function; however, they can fully rescue the wRi modification upon its transfer into their natural hosts (Zabalou et al. 2004a).

Two important points that need to be taken into consideration to determine the CI properties of host–Wolbachia associations are: (a) the host nuclear background and (b) the complete absence of Wolbachia in antibiotic-treated lines (Weeks et al. 2002). Another important factor is the typing of the given Wolbachia strain used in the CI crosses. Efficient methods for Wolbachia strain typing were, until very recently, quite limited and mostly based on the Wolbachia surface protein (wsp) gene (Zhou et al. 1998). However, Wolbachia is prone to high rates of recombination, especially within supergroups, and single gene phylogenetics are unreliable for resolving close relationships (Jiggins et al. 2001; Werren and Bartos 2001; Bordenstein and Wernegreen 2004; Baldo et al. 2005, 2006a).

Taking a new approach to strain typing, Riegler et al. (2005) reported a number of polymorphic markers, such as size polymorphisms for IS5 insertion sites or minisatellites and the orientation of a chromosomal inversion, to detect and discriminate five different Wolbachia variants present in D. melanogaster natural populations and laboratory stocks. Research on Wolbachia depends critically on the ability to distinguish closely related strains to provide a solid foundation for understanding the evolution of phenotypic changes of this variable endosymbiont. Toward this goal, we recently developed an MLST system to discriminate closely related Wolbachia strains (from supergroups A and B) infecting Drosophila species, including all bacterial strains infecting species of the D. melanogaster subgroup (Paraskevopoulos et al. 2006). Baldo et al. (2006b) recently developed a second MLST system, thus increasing the availability of markers for typing closely related Wolbachia strains.

In this study, we initially aimed at characterizing Wolbachia infections (wYak, wTei, and wSan), naturally present in the yakuba complex, with respect to their modification and rescue activities in D. simulans, a highly permissive host for CI expression. Confocal and MLST analysis were also employed for the evaluation of the CI properties. Additionally, we tested the compatibility relationships of wYak, wTei, and wSan with all other Wolbachia infections naturally present in D. simulans (wRi, wHa, wAu, wNo, and wMa) and with wMel. Up to now, the cytoplasmic incompatibility relationships between different variants could always be explained assuming a single pair of modification and rescue factors specific to each variant. This study shows that a single Wolbachia variant can possess multiple rescue factors corresponding to different CI systems. In addition, our results: (a) suggest that wTei behaves in D. simulans as a mod+ resc− strain, (b) unravel unique CI properties, and (c) provide the framework to understand the diversity and the evolution of new CI-compatibility types.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Insects:

All Drosophila stocks used in this study and their origins are presented in Table 1. Flies were grown at 25° on cornflour/sugar/yeast medium as low-density mass cultures, since larval crowding can have a negative effect on the expression of CI (Sinkins et al. 1995). Tetracycline-treated strains were established by rearing flies for two generations on medium containing tetracycline at 0.025% (w/v) final concentration.

TABLE 1.

Drosophila species and strains used in this study and their associated Wolbachia strain

| Species | Strain | Source | Wolbachiaa |

|---|---|---|---|

| D. yakuba | SA3b | Bom Successo, Africai | wYak |

| D. teissieri | 0257.0c | NDSRCj | wTei |

| D. santomea | STO.9d | Bom Successo, Africai | wSan |

| D. simulans | STCPe | Mahe Island, Seychellese | Øk |

| D. simulans | STCP 14 (wYak)f | This study | wYak |

| D. simulans | STCP 18 (wYak)f | This study | wYak |

| D. simulans | STCP 2 (wTei)f | This study | wTei |

| D. simulans | STCP 4 (wTei)f | This study | wTei |

| D. simulans | STCP 1 (wSan)f | This study | wSan |

| D. simulans | STCP 41 (wSan)f | This study | wSan |

| D. simulans | STCP (wMel)g | Poinsot et al. (1998) | wMel |

| D. simulnas | Riverside | Hoffmann et al. (1986) | wRi |

| D. simulans | Hawaii | O'Neill and Karr (1990) | wHa |

| D. simulans | Coffs Harbor | Hoffmann et al. (1996) | wAu |

| D. simulans | Noumea | Merçot et al. (1995) | wNo |

| D. simulans | Madagascar | James and Ballard (2000) | wMa |

| D. simulans | STCP [wRi]h | This study | wRi |

| D. simulans | STCP [wHa]h | This study | wHa |

| D. simulans | STCP [wAu]h | This study | wAu |

| D. simulans | STCP [wNo]h | This study | wNo |

| D. simulans | STCP [wMa]h | This study | wMa |

Based on partial wsp gene sequences and MLST analysis.

The D. yakuba strain SA3 was used as donor to establish the D. simulans STCP 14 (wYak) and D. simulans STCP 18 (wYak) lines.

The D. teissieri strain 0257.0 was used as donor to establish the D. simulans STCP 2 (wTei) and D. simulans STCP 4 (wTei) lines.

The D. santomea strain STO.9 was used as donor to establish the D. simulans STCP 1 (wSan) and D. simulans STCP 41 (wSan) lines.

The D. simulans strain STCP was used as recipient to establish the D. simulans STCP (wYak, wTei, and wSan) lines (Poinsot et al. 1998).

The D. simulans STCP (wYak, wTei, and wSan) lines were produced in this study.

The D. simulans STCP (wMel) line was produced by Poinsot et al. (1998).

Introgressed line produced by series of backcrosses in this study.

Collected by Daniel Lachaise in São Tomé Island (Lachaise et al. 2000).

National Drosophila Species Resource Center.

Ø, uninfected line.

Micro-injections:

Micro-injections were carried out as previously reported (Zabalou et al. 2004a, 2004b). Using a microcapillary needle (Femtotips; Boehringer, Indianapolis), cytoplasm was drawn from infected early embryos and then injected into slightly dehydrated uninfected recipient early embryos.

Introgression lines:

Introgression lines were produced, harboring the cytoplasm of different D. simulans infected lines carrying the Wolbachia strains wRi, wHa, wNo, wAu, and wMa in the genetic background of D. simulans STCP line. These introgression lines were generated by six generations of backcrossing Wolbachia-infected females of a given line to males of D. simulans STCP. This procedure should theoretically result in at least 98% genome replacement and the maintenance of the cytoplasm of the infected parental female.

Nomenclature:

For the purposes of this study, we will use the following nomenclature system to refer to uninfected, transinfected (through micro-injections), and introgression lines. The name of each line starts with the species name and strain indicating the host genetic background followed by an italicized lower case w followed by the name of the Wolbachia strain within parentheses (transinfected lines) or within square brackets (introgression lines). Zero within parentheses or square brackets denotes an uninfected host. Thus, D. simulans STCP (wYak) symbolizes a transinfected line, D. simulans STCP [wHa] an introgression line, while D. simulans STCP (Ø) symbolizes an uninfected line.

Detection, typing, and phylogenetic analysis of Wolbachia strains:

Bacterial DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The presence of Wolbachia was initially determined by PCR using the 16S rDNA Wolbachia-specific primers 99F and 994R, which yield a product of ∼900 bp (O'neill et al. 1992) and the wsp primers 81F and 691R, which yield a product of ∼600 bp (Braig et al. 1998; Zhou et al. 1998). PCR control reactions were performed to test the quality of the DNA template using the mitochondrial cytb primers cytb1 and cytb2, which yield a 378-bp product (Clary and Wolstenholme 1985). PCR conditions have been described in detail previously (Paraskevopoulos et al. 2006). The typing of the Wolbachia strains was based on a recently developed MLST approach (Paraskevopoulos et al. 2006) and partial sequencing of the wsp gene. Furthermore, the same sequence gene data were concatenated and phylogenetic relationships were determined with PhyloBayes, a Bayesian Monte Carlo Markov Chain (MCMC) sampler (Lartillot and Philippe 2004). The CAT mixture model was used to account for site-specific features of protein evolution. Seven independent runs were performed with a total length of 10,000 cycles. The burn-in value was set at 0.95; the posterior consensus was computed on the 9500 remaining trees.

CI measurements:

All matings were set up with one virgin female (3 days old) and one virgin male (up to 1 day old). Crosses were performed at 25° in bottles upturned on agar/molasses plastic Petri dishes. Males were removed after mating to avoid remating and females left to lay eggs for 2–3 days. The dishes were replaced daily to monitor the number of eggs laid. Females that laid <25 eggs were not included in the analysis. Hatching rates were scored 36 hr after egg collection. The parents of each cross were tested by PCR for the presence of Wolbachia. The females and males from those crosses that did not produce any larval progeny were tested for fertility by crossing with a compatible partner. Crosses from sterile females or males were excluded from further analysis.

mod intensity:

To determine if a given Wolbachia strain expresses the mod function in its natural hosts, and if yes, with which penetrance, uninfected females were mated with both infected and uninfected males of the same genetic background. Strains for which embryonic mortality is significantly higher in crosses with infected males are considered mod+. The same test was performed with the transinfected lines.

Compatibility relationships:

To test if a given Wolbachia strain (e.g., wA) can rescue the mod function of another Wolbachia strain (e.g., wB), males bearing wB were crossed with females bearing wA, as well as with uninfected females of the same genetic background. Rescue is detected if embryonic mortality is significantly reduced by the presence of wA in females.

Statistical analysis:

Statistical analysis was performed using various generalized linear models (GLM) with normal error and the identity link function (Nelder and Wedderburn 1972; McCullagh and Nelder 1989). Factors used in these analyses include “bacterial strain” (separately in males and in females) and “experimental location” (Greece and France). More details are given at each analysis in the results section. Significance level was set to 5% for all analyses performed. SPSS (SPSS for Windows 15.0; SPSS, Chicago) was used for all these models.

Immunofluorescence:

Embryos, ovaries, and testes from 1-day-old flies were stained with the Wolbachia surface protein (WSP) antibody and propidium iodide (PI) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), as described previously (Veneti et al. 2003, 2004). Images were taken using a Leica confocal laser-scanning microscope, and Adobe Photoshop 7.0 was used for editing purposes. For each of the three types of transinfected lines used in this study, 10 blastoderm-stage embryos stained with WSP antibody were used for fluorescence quantification. For each embryo, 1.5 μm-thick sections were taken and fluorescent pixels for the image stacks were measured using the ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

RESULTS

Zabalou et al. (2004a) showed that naturally Wolbachia-infected D. yakuba SA3 (wYak), D. teissieri 0257.0 (wTei), and D. santomea STO.9 (wSan) lines do not express CI. However, upon transfer of wRi in native hosts of the above strains, it was observed that all three are able to fully rescue the wRi modification. The question raised by this study was whether the mod− phenotype observed in the three species forming the yakuba complex is due to a host or a bacterial property. This study attempts to address this question through the transfer of the wYak, wTei, and wSan infections to another host, D. simulans, which is one of the most permissive Drosophila species for the expression of CI, as well as a known natural host of at least five Wolbachia strains.

Establishment of transinfected lines:

Injections of an uninfected (tetracycline-cured) line of D. simulans (Poinsot et al. 1998), called from now on STCP, were performed using the naturally Wolbachia-infected D. yakuba SA3 (wYak), D. teissieri 0257.0 (wTei), and D. santomea STO.9 (wSan) as donor lines. The Wolbachia strains wYak, wTei, and wSan were successfully transferred to and established in the STCP strain. Two wYak, six wTei, and four wSan-transinfected D. simulans STCP lines were obtained (Table 2). Transinfections were confirmed by PCR of the 16S rDNA and wsp genes of Wolbachia. At the time of writing, all transinfected lines are still stably infected with no evidence of loss of infection for >200 generations. Two stably transinfected D. simulans STCP lines for each Wolbachia strain were used in crossing experiments in the Greek laboratories, while one of the lines was also independently characterized in the French laboratory (Table 1). Mann–Whitney tests were carried out, prior to the GLM analysis presented below, to compare these lines in all crossing experiments performed in Greece. No differences were found between the two stably transinfected D. simulans STCP lines for each Wolbachia strain (data not shown), and so we decided to pool these data.

TABLE 2.

Summary of transinfection experiments

| Recipient: | Donor

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| D. simulans STCP (ø) | D. yakuba SA3 (wYak) (%) | D. teissieri 0257.0 (wTei) (%) | D. santomea STO.9 (wSan) (%) |

| Injected embryos | 1080 | 720 | 1380 |

| Survived G0 larvae | 193 (17.9)a | 70 (9.7)a | 400 (28.9)a |

| Survived G0 females | 26 (13.5)b | 37 (52.9)b | 44 (11.0)b |

| Fertile G0 females | 22 (84.6)c | 35 (94.6)c | 40 (90.9)c |

| Wolbachia-infected G0 females | 2 (9.1)d | 6 (17.1)d | 4 (10.0)d |

Percentage of hatched G0 larvae.

Percentage of survived G0 females.

Percentage of fertile G0 females.

Percentage of Wolbachia-infected G0 females.

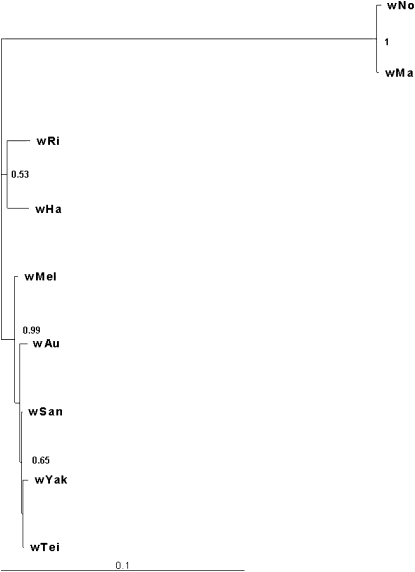

Transinfected and introgression lines were used to perform a total of 1710 crosses (Table 3) in an attempt to study the compatibility relationships between nine different Wolbachia strains (wMel, wYak, wTei, wSan, wAu, wRi, wHa, wNo, and wMa) in a control host genomic background (D. simulans STCP). The phylogenetic relationships of these Wolbachia strains, based on the neighbor-joining phylogenetic analysis of the concatenated gene fragments, are shown in Figure 1.

TABLE 3.

Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP lines and expression of CI

| Female infection | Male infection

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STCP | wYak | wTei | wSan | wRi | wMel | wAu | wHa | wNo | wMa | |

| A. Expression of cytoplasmic incompatibility (expressed as percentage embryonic mortality ± SE) in transinfected and introgression D. simulans STCP lines carrying different Wolbachia strains | ||||||||||

| Greece | ||||||||||

| STCP | 13.6 ± 3.0 | 26.5 ± 4.2 | 97.2 ± 1.3 | 24.0 ± 4.1 | 89.8 ± 4.5 | 15.6 ± 2.9 | 75.4 ± 6.5 | 45.8 ± 7.3 | 11.7 ± 3.4 | |

| wYak | 5.3 ± 0.8 | 15.7 ± 4.3 | 39.8 ± 7.1 | 34.4 ± 5.6 | 21.2 ± 4.6 | 76.0 ± 5.6 | 45.8 ± 7.3 | 8.8 ± 1.8 | ||

| wTei | 11.3 ± 2.0 | 25.3 ± 6.9 | 37.3 ± 3.3 | 10.1 ± 2.8 | 25.2 ± 2.3 | 15.0 ± 4.6 | 79.5 ± 7.7 | 56.9 ± 5.0 | 6.6 ± 1.5 | |

| wSan | 10.3 ± 2.8 | 45.2 ± 7.6 | 12.2 ± 1.6 | 40.3 ± 4.1 | 9.4 ± 4.3 | 69.6 ± 6.4 | 40.3 ± 5.0 | 9.0 ± 2.2 | ||

| wRi | 23.7 ± 4.0 | 27.8 ± 4.6 | 79.5 ± 6.0 | 24.5 ± 3.5 | 34.9 ± 8.7 | 23.8 ± 4.1 | 64.8 ± 5.7 | 64.4 ± 5.9 | 23.5 ± 6.7 | |

| wAu | 15.3 ± 2.0 | 12.8 ± 2.8 | 94.2 ± 2.7 | 16.3 ± 4.5 | 96.5 ± 1.7 | 10.5 ± 2.5 | 59.8 ± 6.3 | |||

| wHa | 12.5 ± 2.5 | 11.3 ± 2.2 | 93.5 ± 3.0 | 8.5 ± 1.4 | 91.4 ± 3.6 | 6.0 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 0.8 | |||

| wNo | 19.1 ± 3.0 | 17.1 ± 6.0 | 80.6 ± 4.8 | 16.1 ± 4.0 | 88.2 ± 3.7 | 39.0 ± 8.4 | 9.3 ± 1.8 | |||

| wMa | 13.7 ± 2.3 | 25.0 ± 4.6 | 57.2 ± 6.9 | 15.2 ± 2.5 | 88.7 ± 5.1 | 62.7 ± 5.5 | 13.2 ± 3.9 | |||

| France | ||||||||||

| STCP | 12.5 ± 2.9 | 21.0 ± 4.5 | 99.9 ± 0.1 | 24.2 ± 6.4 | 99.6 ± 0.2 | |||||

| wYak | 16.6 ± 2.8 | 17.9 ± 6.4 | 66.3 ± 6.8 | 93.1 ± 3.0 | ||||||

| wTei | 13.1 ± 1.7 | 53.5 ± 4.5 | 37.0 ± 5.3 | |||||||

| wSan | 16.5 ± 4.2 | 55.5 ± 7.9 | 6.7 ± 1.3 | 96.2 ± 1.7 | ||||||

| wMel | 49.1 ± 7.1 | 99.0 ± 0.3 | 39.0 ± 7.4 | |||||||

| B. No. of eggs (no. of crosses) used to determine the levels of cytoplasmic incompatibility presented in A | ||||||||||

| Greece | ||||||||||

| STCP | 1668 (27) | 2635 (33) | 1907 (30) | 2441 (32) | 1322 (19) | 1460 (16) | 917 (14) | 1395 (17) | 1447 (24) | |

| wYak | 2683 (31) | 1794 (21) | 545 (10) | 1660 (23) | 1567 (19) | 1207 (16) | 1164 (16) | 1627 (24) | ||

| wTei | 1409 (24) | 658 (10) | 3156 (43) | 835 (13) | 3124 (35) | 1045 (15) | 1101 (15) | 1650 (18) | 1349 (16) | |

| wSan | 1641 (21) | 1114 (17) | 2389 (31) | 2215 (33) | 924 (16) | 894 (14) | 2038 (28) | 1278 (19) | ||

| wRi | 1981 (24) | 1894 (24) | 1094 (18) | 1631 (22) | 1000 (13) | 1650 (24) | 1421 (23) | 1090 (14) | 931 (17) | |

| wAu | 1272 (17) | 1092 (16) | 1566 (21) | 1211 (18) | 1404 (18) | 1315 (20) | 1047 (14) | |||

| wHa | 882 (16) | 1298 (18) | 1429 (24) | 898 (16) | 882 (16) | 1063 (19) | 1283 (21) | |||

| wNo | 1322 (15) | 1127 (17) | 1592 (26) | 1013 (16) | 1226 (17) | 1092 (14) | 872 (13) | |||

| wMa | 1386 (19) | 1656 (23) | 1572 (25) | 1522 (21) | 1327 (19) | 1433 (22) | 1141 (18) | |||

| France | ||||||||||

| STCP | 1455 (15) | 1898 (18) | 1598 (19) | 1664 (17) | 2312 (23) | |||||

| wYak | 1466 (15) | 917 (9) | 1026 (12) | 1346 (16) | ||||||

| wTei | 1247 (15) | 1251 (15) | 961 (11) | |||||||

| wSan | 1389 (14) | 959 (12) | 858 (9) | 1921 (23) | ||||||

| wMel | 588 (8) | 901 (12) | 639 (9) | |||||||

Figure 1.—

Phylogenetic tree of the Wolbachia strains, constructed using the program MEGA 4.0 on the basis of the neighbor-joining method. Values on the branches represent the percentage of 10,000 bootstrap replicates.

An initial analysis of the embryonic mortalities resulting from these crosses was carried out by a GLM with bacterial strain (in males and in females) and experimental location as factors. A significant interaction was found by this analysis (P < 0.001) and therefore separate generalized linear models were run to determine the modification and the rescue properties of the Wolbachia strains, particularly those of wYak, wTei, and wSan. It is also important to note that no major differences were observed in the results of the crossing experiments between the two locations (Greece and France).

Do wYak-, wTei-, and wSan-transinfected D. simulans STCP lines express CI?

All Wolbachia-infected (transinfected and introgression) D. simulans STCP lines were repeatedly and independently tested for the expression of the mod function in appropriate single-pair crosses. All data concerning these crosses are presented in Table 3. A GLM statistical analysis was carried out with “bacterial strain in males” and experimental location as factors. The model proved to be highly significant (likelihood ratio = 481.5, P < 0.001). The estimated b-parameters (along with their 95% confidence intervals) and P-values are presented in Table 4. These data suggest that all Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP lines tested are able to express CI with the exception of the wAu- and wMa-infected ones. The Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP lines that express CI can be classified into three groups according to the 95% confidence intervals of the b-parameters: (a) the first group includes the wMel-, wRi-, and wTei-infected D. simulans STCP lines that express “high” levels of CI (mean CI 89.8–99.9% as shown in Table 3); (b) the second group includes the wHa and wNo-infected D. simulans STCP lines that express “medium” levels of CI (45.8–75.4%); and (c) the third group includes the wYak- and wSan-infected D. simulans STCP lines that express “low” levels of CI (21.0–26.5%). These data indicate that the wYak, wTei, and wSan Wolbachia strains are able to induce CI in D. simulans STCP genomic background while they were unable to induce this reproductive alteration in their natural host (Zabalou et al. 2004a). It is worth noting that the wTei- transinfected D. simulans STCP lines express very high levels of CI (nearly 100%). Is this phenotypic change due to a host or to a bacterial factor(s)?

TABLE 4.

Generalized linear model results on the modification properties of the Wolbachia strains used in this study

| 95% Wald confidence interval

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male infection | b | Lower | Upper | χ2 | d.f. | P-value |

| (Intercept) | 3.777 | 3.278 | 4.275 | 220.753 | 1 | 0.000 |

| wYak | −0.114 | −0.188 | −0.040 | 9.188 | 1 | 0.002a* |

| wTei | −0.851 | −0.925 | −0.776 | 502.798 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wSan | −0.109 | −0.183 | −0.034 | 8.204 | 1 | 0.004a* |

| wRi | −0.763 | −0.862 | −0.663 | 225.310 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wMel | −0.870 | −0.968 | −0.772 | 303.383 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wAu | −0.021 | −0.126 | 0.085 | 0.150 | 1 | 0.699a |

| wNo | −0.323 | −0.426 | −0.220 | 37.494 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wHa | −0.619 | −0.729 | −0.508 | 119.853 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wMa | 0.018 | −0.075 | 0.110 | 0.143 | 1 | 0.706a |

| Location | 0.009 | −0.044 | 0.062 | 0.113 | 1 | 0.737b |

*Significant at 5% level.

P-value for the comparison of the “modification” cross (D. simulans STCP female × Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP male) to the control cross (D. simulans STCP female × D. simulans STCP male)

P-value for the comparison between the data obtained in Greece and France.

The rescue properties of the Wolbachia strains, particularly those of wTei, wYak, and wSan, used in this study were assessed by different GLMs carried out with “bacterial strain in females” and experimental location as factors. The results of these analyses are presented below and in Tables 5–10.

TABLE 5.

Generalized linear model results on the rescue potential of different Wolbachia strains against the wTei modification

| 95% Wald confidence interval

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female infection | b | Lower | Upper | χ2 | d.f. | P-value |

| (Intercept) | −1.139 | −1.693 | −0.585 | 16.223 | 1 | 0.000 |

| wYak | 0.459 | 0.353 | 0.565 | 71.657 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wTei | 0.552 | 0.471 | 0.632 | 180.636 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wSan | 0.491 | 0.394 | 0.588 | 99.376 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wRi | 0.141 | 0.024 | 0.257 | 5.573 | 1 | 0.018a* |

| wMel | 0.066 | −0.073 | 0.206 | 0.875 | 1 | 0.350a |

| wAu | −0.006 | −0.117 | 0.105 | 0.012 | 1 | 0.912a |

| wNo | 0.130 | 0.026 | 0.233 | 6.033 | 1 | 0.014a* |

| wHa | 0.001 | −0.105 | 0.107 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.990a |

| wMa | 0.363 | 0.258 | 0.468 | 46.165 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| Location | −0.121 | −0.191 | −0.052 | 11.771 | 1 | 0.001b* |

*Significant at 5% level.

P-value for the comparison of the “rescue” cross (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP female × wTei-infected D. simulans STCP male) to the control cross (D. simulans STCP female × wTei-infected D. simulans STCP male)

P-value for the comparison between the data obtained in Greece and France.

TABLE 10.

Compatibility relationships (expressed in D. simulans STCP background) between the Wolbachia strains used in this study

| Male infection

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female infection | wYak | wTei | wSan | wRi | wMel | wAu | wHa | wNo | wMa | |

| STCP | Low CI | High CI | Low CI | High CI | High CI | No CI | Medium CI | Medium CI | No CI | |

| wYak | NAa | Low CI | NDb | No to low CI | High CI | No CI | Medium CI | Medium CI | No CI | |

| wTei | NA | Low CI | NA | No to low CI | Low CI | No CI | Medium CI | Medium CI | No CI | |

| wSan | NA | Low CI | NA | No to low CI | High CI | No CI | Medium CI | Medium CI | No CI | |

| wRi | NA | Medium to high CI | NA | No to low CI | No to low CIc | No CI | Medium CI | Medium CI | No CI | |

| wMel | NA | High CI | NA | Medium CIc | No CI | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| wAu | NA | High CI | NA | High CI | ND | No CI | ND | Medium CI | ND | |

| wHa | NA | High CI | NA | High CI | ND | ND | No CI | ND | No CI | |

| wNo | NA | High CI | NA | High CI | ND | No CI | ND | No CI | ND | |

| wMa | NA | Medium CI | NA | High CI | ND | ND | Medium CI | No CId | No CI | |

CI, cytoplasmic incompatibility

NA, not assessed (as discussed in the text, the rescue potential of different Wolbachia strains against the wYak and wTei modification cannot be validly determined due to the low levels of CI expressed in wYak- and wSan-infected D. simulans STCP lines).

ND, these crosses have not been performed in the D. simulans STCP genomic background.

Based on previous reports (Poinsot et al. 1998).

Based on previous reports (Bourtzis et al. 1998; Merçot and Poinsot 1998a,b).

TABLE 6.

Generalized linear model results on the rescue potential of different Wolbachia strains against the wRi modification

| 95% Wald confidence interval

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male infection | b | Lower | Upper | χ2 | d.f. | P-value |

| (Intercept) | −1.288 | −1.956 | −0.620 | 14.276 | 1 | 0.000 |

| wYak | 0.554 | 0.434 | 0.673 | 81.950 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wTei | 0.646 | 0.536 | 0.756 | 132.124 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wSan | 0.495 | 0.383 | 0.606 | 75.836 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wRi | 0.549 | 0.410 | 0.688 | 59.724 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wAu | −0.067 | −0.194 | 0.060 | 1.073 | 1 | 0.300a |

| wNo | 0.016 | −0.113 | 0.145 | 0.060 | 1 | 0.806a |

| wHa | −0.016 | −0.148 | 0.115 | 0.060 | 1 | 0.806a |

| wMa | 0.011 | −0.115 | 0.136 | 0.027 | 1 | 0.868a |

*Significant at 5% level.

P-value for the comparison of the “rescue” cross (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP female × wRi-infected D. simulans STCP male) to the control cross (D. simulans STCP female × wRi-infected D. simulans STCP male)

TABLE 7.

Generalized linear model results on the rescue potential of different Wolbachia strains against the wMel modification

| 95% Wald confidence interval

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male infection | b | Lower | Upper | χ2 | d.f. | P-value |

| (Intercept) | −0.335 | −0.522 | −0.148 | 12.308 | 1 | 0.000 |

| wYak | 0.065 | −0.007 | 0.138 | 3.095 | 1 | 0.079a |

| wTei | 0.626 | 0.544 | 0.708 | 223.920 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wSan | 0.034 | −0.032 | 0.100 | 1.004 | 1 | 0.316a |

| wMel | 0.606 | 0.518 | 0.694 | 182.314 | 1 | 0.000a* |

*Significant at 5% level.

P-value for the comparison of the “rescue” cross (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP female × wMel-infected D. simulans STCP male) to the control cross (D. simulans STCP female × wMel-infected D. simulans STCP male)

TABLE 8.

Generalized linear model results on the rescue potential of different Wolbachia strains against the wHa modification

| 95% Wald confidence interval

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male infection | b | Lower | Upper | χ2 | d.f. | P-value |

| (Intercept) | −0.184 | −0.846 | 0.479 | 0.294 | 1 | 0.587 |

| wYak | −0.006 | −0.173 | 0.160 | 0.006 | 1 | 0.940a |

| wTei | −0.042 | −0.210 | 0.127 | 0.232 | 1 | 0.630a |

| wSan | 0.058 | −0.113 | 0.230 | 0.444 | 1 | 0.505a |

| wRi | 0.106 | −0.048 | 0.260 | 1.809 | 1 | 0.179a |

| wHa | 0.694 | 0.534 | 0.854 | 72.275 | 1 | 0.000a* |

| wMa | 0.127 | −0.028 | 0.282 | 2.568 | 1 | 0.109a |

*Significant at 5% level.

P-value for the comparison of the “rescue” cross (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP female × wHa-infected D. simulans STCP male) to the control cross (D. simulans STCP female × wHa-infected D. simulans STCP male)

TABLE 9.

Generalized linear model results on the rescue potential of different Wolbachia strains against the wNo modification

| 95% Wald confidence interval

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male infection | b | Lower | Upper | χ2 | d.f. | P-value |

| (Intercept) | 0.474 | −0.160 | 1.107 | 2.146 | 1 | 0.143 |

| wYak | 0.000 | −0.162 | 0.163 | 0.000 | 1 | 0.995a |

| wTei | −0.111 | −0.268 | 0.047 | 1.890 | 1 | 0.169a |

| wSan | 0.055 | −0.088 | 0.199 | 0.571 | 1 | 0.450a |

| wRi | −0.186 | −0.354 | −0.018 | 4.692 | 1 | 0.030a* |

| wAu | −0.140 | −0.308 | 0.028 | 2.653 | 1 | 0.103a |

| wNo | 0.366 | 0.194 | 0.538 | 17.382 | 1 | 0.000a* |

*Significant at 5% level.

P-value for the comparison of the “rescue” cross (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP female × wNo-infected D. simulans STCP male) to the control cross (D. simulans STCP female × wNo-infected D. simulans STCP male)

Which Wolbachia strains rescue the wTei modification in the D. simulans STCP background?

The GLM analysis was shown to be highly significant (likelihood ratio = 226.24, d.f. = 10, P < 0.001). The estimated b-parameters (along with their 95% confidence intervals) and P-values are presented in Table 5. The data suggest that the wTei, wYak, wSan, wRi, wNo, and wMa strains can rescue the wTei modification while the wMel, wAu, and wHa cannot. The Wolbachia strains that rescue the wTei modification can be classified into two groups according to the 95% confidence intervals of the b-parameters: the first group includes the wTei, wYak, wSan, and wMa strains that exhibit high levels of rescue capacity (mean CI 37.3–66.3% as shown in Table 3), while the second group includes the wNo and wRi strains that exhibit low levels of rescue potential (mean CI 79.5–80.6%). It should be noted that the crosses performed in France showed slightly lower levels of rescue potential; however, no qualititative differences were observed (Tables 3 and 5).

The efficiency of the wTei, wYak, and wSan strains to rescue the wTei modification was also assessed by a GLM analysis. A comparison between the “rescue” crosses (wTei-, wYak-, and wSan-infected D. simulans STCP females × wTei-infected males) to the control ones (wTei-, wYak-, and wSan-infected D. simulans STCP females × D. simulans STCP males), taking into account the experimental location, was performed. A significant difference was observed in the comparison between the ‘rescue crosses and the control crosses (Wald's χ2 = 28.56, d.f. = 1, P < 0.001). These data clearly suggest that the wTei, wYak, and wSan strains cannot completely rescue the wTei modification.

Do the wYak, wTei, and wSan Wolbachia strains rescue the wRi modification in the D. simulans STCP background?

Zabalou et al. (2004a) showed that naturally Wolbachia-infected D. yakuba SA3 (wYak), D. teissieri 0257.0 (wTei), and D. santomea STO.9 (wSan) lines could fully rescue the wRi modification upon its transfer in their native hosts. Is this rescue function also observed in the D. simulans STCP background? To address this question, it was necessary to study all Wolbachia strains in the same host background. The wRi strain was transferred into D. simulans STCP through a series of backcrosses. A comparison between the rescue crosses (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP females × wRi-infected males) to the control ones (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP females × D. simulans STCP males) was performed as shown in Table 3. The GLM statistical analysis was highly significant (likelihood ratio = 223.73, d.f. = 8, P < 0.001). The estimated b-parameters (along with their 95% confidence intervals) and P-values are presented in Table 6. These data suggest that wTei, wYak, wSan, and wRi can rescue the wRi modification while wAu, wHa, wNo, and wMa cannot.

The data also suggest that the wTei, wYak, and wSan strains may equally efficiently rescue the wRi modification in the D. simulans STCP background and that the rescue of the wRi modification is as efficient as the one performed by wRi itself (Table 6).

Do the wYak, wTei, and wSan Wolbachia strains rescue the wMel modification in the D. simulans STCP background?

The wMel Wolbachia strain has been reported as a mod+ resc+ strain in previous studies (Hoffmann 1988; Bourtzis et al. 1994, 1996). About 10 years ago, we transferred the wMel Wolbachia strain into the D. simulans STCP background and showed that it induces high levels of CI (Poinsot et al. 1998). The fact that all four Wolbachia strains (wYak, wTei, wSan, and wMel) are present in the same host genomic background, D. simulans STCP, provided the opportunity to address the above question through a comparison between the rescue crosses (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP females × wMel-infected males) to the control ones (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP females × D. simulans STCP males) as shown in Table 3. The GLM statistical analysis was highly significant (likelihood ratio = 145.95, d.f. = 4, P < 0.001). The estimated b-parameters (along with their 95% confidence intervals) and P-values are presented in Table 7. These data suggest that only the wTei strain can rescue the wMel modification (equally well as wMel, as is evident from the confidence intervals of their respective b-parameters) while the wYak and wSan strains cannot.

Do the wYak, wTei, and wSan Wolbachia strains rescue the wHa modification in the D. simulans STCP background?

Wolbachia strain wHa has been reported as a mod+ resc+ strain in previous studies (O'Neill and Karr 1990). The wHa strain was transferred into D. simulans STCP through a series of backcrosses, thus providing the potential to address the above question through a comparison between the rescue crosses (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP females × wHa-infected males) to the control ones (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP females × D. simulans STCP males) as shown in Table 3. The GLM statistical analysis was highly significant (likelihood ratio = 89.35 d.f. = 6, P < 0.001). The estimated b-parameters (along with their 95% confidence intervals) and P-values are presented in Table 8. These data suggest that only the wHa strain can rescue its own modification while the wTei, wYak, wSan, wRi, and wMa strains cannot.

Do the wYak, wTei, and wSan Wolbachia strains rescue the wNo modification in the D. simulans STCP background?

Wolbachia strain wNo has been reported as a mod+ resc+ strain in previous studies (Merçot et al. 1995). The strain was transferred into D. simulans STCP through a series of backcrosses, thus providing the potential to address the above question through a comparison between the rescue crosses (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP females × wNo-infected males) to the control ones (Wolbachia-infected D. simulans STCP females × D. simulans STCP males), as shown in Table 3. The GLM statistical analysis was highly significant (likelihood ratio = 41.41, d.f. = 6, P < 0.001). The estimated b-parameters (along with their 95% confidence intervals) and P-values are presented in Table 9. These data suggest that only the wNo strain can rescue the wNo modification while the wTei, wYak, wSan, and wAu strains cannot. The significant difference found for the b-coefficient of wRi means that this strain not only fails to rescue the wNo modification, but it actually increases the observed embryonic mortality.

Typing Wolbachia strains in transinfected lines:

We have recently developed and applied an MLST system to type Wolbachia strains infecting different Drosophila species (Paraskevopoulos et al. 2006). This MLST approach was used to type the Wolbachia strains present in all donor and transinfected lines used in our study. The results were as follows: (a) both donor and transinfected Drosophila lines harbor Wolbachia strains with identical MLST profiles, and (b) no evidence of multiple infections was observed in any of the donor and the transinfected lines. In addition, we sequenced part of the wsp gene of the Wolbachia strains present in both the donor and the wYak-, wTei-, and wSan-transinfected lines: all sequences obtained were identical to one another and closely related to that of the D. simulans Coffs Harbor Wolbachia strain (wAu, EMBL accession no. AF020067) analyzed by Zhou et al. (1998). These results are consistent with those reported by Charlat et al. (2004) and Zabalou et al. (2004a). Taken together, these data suggest that the donor lines D. yakuba (wYak), D. teissieri (wTei), and D. santomea (wSan) and the wYak-, wTei-, and wSan-transinfected D. simulans STCP lines carry very closely related Wolbachia strains (Table 1).

Immunofluorescence analysis:

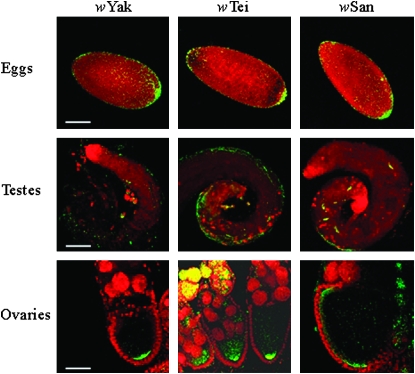

Immunofluorescence experiments and confocal analysis were performed in embryos, testes, and ovaries of wYak-, wTei-, and wSan-transinfected D. simulans STCP lines, using an anti-WSP antiserum as described previously (Clark et al. 2002, 2003; Veneti et al. 2003, 2004). Our analysis shows that the D. simulans STCP (wYak), D. simulans STCP (wTei), and D. simulans STCP (wSan) lines carried 4000 ± 200, 3900 ± 600, and 1700 ± 200 bacterial counts respectively. ANOVA analysis indicated significant differences between the bacterial densities of embryos of the three transinfected lines (F = 11.70, d.f. = 2.27, P < 0.001). Tukey's honestly significant differences (HSD) test showed grouping of wYak-infected and wTei-infected D. simulans STCP lines together, while the wSan-infected D. simulans STCP line exhibited the lowest numbers. Overall, embryos from all three transinfected lines exhibited relatively low Wolbachia densities and tight posterial localization (Figure 2), similar to those observed in the native hosts (Veneti et al. 2004). The vast majority of the sperm cysts of all three transinfected lines used in this study were uninfected. Only a small number (<5%) contained few bacteria, probably scattered in the somatic part of the testes (Figure 2), as it has been described for their native hosts (Veneti et al. 2003). Finally, the Wolbachia distribution in ovaries showed bacterial accumulation in the posterior part of the oocyte (Figure 2), as observed for the native hosts (Veneti et al. 2004). We therefore conclude that the D. simulans genomic background did not significantly affect the distribution of the wYak, wTei, and wSan bacteria.

Figure 2.—

Representative Wolbachia density and distribution is shown in embryos at syncytial blastoderm stage, testes and ovaries of wYak-infected, wTei-infected, and wSan-infected D. simulans STCP lines. Wolbachia are stained green-yellow and host nuclei red. Most bacteria are concentrated in the posterior part of the eggs and oocytes. Eggs are oriented with the anterior part to the left. A few bacteria are scattered across the testes, and infected sperm cysts are rare, if present at all, in all three lines. Wolbachia cells are abundant in the ovaries, especially in the early stages of oogenesis for all three lines tested (shown only for wTei-infected ovary). For later stages, no real differences between the three lines are observed. Scale bar: embryos, 100 μm; testes, 100 μm; ovaries, 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

Zabalou et al. (2004a) have shown that the naturally occurring host–Wolbachia associations D. yakuba SA3 (wYak), D. teissieri 0257.0 (wTei), and D. santomea STO.9 (wSan) do not express CI, but that they are able to fully rescue the wRi modification in the corresponding wRi transinfected native hosts. This poses the question whether the modification function is absent from these Wolbachia strains or merely hidden in the native hosts. Transfers of the Wolbachia strains into the same D. simulans (STCP) genomic background, through either embryonic cytoplasmic injections or introgressions, enabled us to address this question as well as to study the compatibility relationships of wYak, wTei, and wSan with other Wolbachia strains (Weeks et al. 2002).

Transinfection experiments are a powerful tool in studies of host–Wolbachia interactions; it should, however, be used with caution. Transinfections may result in the transfer of “hidden” Wolbachia strains to the new host, where they may find a suitable environment for multiplication and persistence (for a documented case see Zabalou et al. 2004b). It is therefore important to always type the transferred Wolbachia strain(s). Using a recently developed MLST approach (Paraskevopoulos et al. 2006), we typed all Wolbachia strains present in naturally infected, transinfected, and introgressed Drosophila lines used in this study.

The phenotypic shift:

The wYak, wTei, and wSan strains are very closely related judging from their identical wsp gene sequences (Lachaise et al. 2000; Zabalou et al. 2004a) and their position in the same MLST-assigned clonal complex (Paraskevopoulos et al. 2006). All three strains were transferred from their native hosts (D. yakuba, D. teissieri, and D. santomea) to D. simulans STCP through cytoplasmic injections. The transinfected lines were used in single-pair genetic crosses to study their CI properties (Table 3). A clear phenotypic shift was observed upon the transfer from their native hosts to D. simulans STCP. It was observed that the wYak- and wSan-transinfected D. simulans STCP lines expressed low levels of CI, while the transinfected D. simulans STCP (wTei) symbiotic association expressed very high levels of CI (nearly 100%). According to Veneti et al. (2003), there are three requirements for the expression of CI in a host–Wolbachia association: (i) Wolbachia has to be able to modify sperm (mod+ genotype), (ii) Wolbachia has to be harbored by a permissive host, and (iii) Wolbachia has to infect sperm cysts. How can this phenotypic shift from mod− to mod+ be explained? There are at least four possible explanations:

It could be that the new host environment of D. simulans STCP is permissive for the expression of the modification function of wYak, wTei, and wSan. Previous reports showed similar phenotypic changes in the behavior of Wolbachia strains upon their transfer to novel hosts (Poinsot et al. 1998). Bordenstein et al. (2003) also showed that host genotype rather than Wolbachia strain differences determines the type and levels of cytoplasmic incompatibility in the Nasonia species complex (but see also Bordenstein and Werren 2007). In addition, recent transinfection experiments showed that the same Wolbachia variant could induce two distinct reproductive phenotypes, CI and male killing, in different host species (Sasaki et al. 2005).

-

Significant differences in the percentage of infected spermatocysts could exist between the native and the transinfected symbiotic associations. Confocal analysis did not provide evidence for this: there was no difference in either the distribution and density or the percentage of the native and the transinfected symbiotic associations (Figure 2; see also Veneti et al. 2003). It remains possible, however, that differences in the wTei (wYak or wSan) replication rate in larval testes could explain the ability of wTei (wYak or wSan) to modify the paternal chromosomes. Alternatively, sperm could be modified at some point in development, where differences in Wolbachia distribution and density cannot be detected (Clark et al. 2002, 2003; Veneti et al. 2003).

Also, the distribution and infection levels of wYak, wTei, and wSan in embryos and ovaries of the transinfected D. simulans STCP lines was not different from that observed in their native hosts (Veneti et al. 2004).

The transfer of Wolbachia-infected embryonic cytoplasm from the native hosts could result in the establishment of a previously undetected mod+ strain(s) in the novel host D. simulans STCP. Given the uncultivable nature of Wolbachia, this hypothesis was investigated on the basis of MLST and wsp gene sequencing analyses. The results were clear: (a) both naturally infected and transinfected lines carry Wolbachia strains having identical MLST profiles and wsp gene sequences and (b) no evidence of multiple infections was observed in any of the donor or the transinfected lines. Thus, a transfer of a previously undetected mod+ strain from the native hosts to the novel D. simulans STCP is not likely to have occurred.

If we assume that wTei (wYak or wSan) is a genotypically mod− strain in its native host, then the fourth possible explanation could be a genotypic change of wTei (wYak or wSan) from mod− to mod+ upon its transfer to the novel host D. simulans STCP. This genetic change could be due to a single point mutation, a chromosomal rearrangement, a recombination event, or a transposable element. All of these explanations are made extremely unlikely by the fact that more than one line with mod+ phenotype for each one of the three Wolbachia strains (wYak, wTei, and wSan) was generated through their transfer to D. simulans STCP.

Bordenstein et al. (2006) recently suggested that Wolbachia symbiosis should be considered as a tripartite association between the host, the bacterium, and the phage. If the phage plays indeed a causative role in the modification mechanism, and if the D. teissieri host background is more permissive for the lytic action of the endogenous wTei phage(s) compared to the D. simulans STCP background, the presence of the same Wolbachia strain could result in low CI levels in D. teissieri due to the high lytic action of Wolbachia phase (WO) and high CI levels in D. simulans due to the low lytic phage activity. In any case, if phage activity is different in native and transinfected hosts, differences in density should be expected. Our currently available data do not support this hypothesis.

On the basis of the above and considering the available genetic, cellular, and molecular evidence it seems most likely that D. simulans STCP is a more permissive host for CI expression by wTei, wYak, and wSan than their native hosts, D. teissieri, D. yakuba, and D. santomea, respectively.

Compatibility relationships:

The presence of nine different Wolbachia strains belonging to the A and B supergroups (wYak, wTei, wSan, wRi, wMel, wHa, wAu, wNo, and wMa) in the same host genomic background (D. simulans STCP) made genetic crosses possible to study their compatibility relationships. The crosses revealed interesting compatibility patterns between wYak, wTei, wSan, and the other Wolbachia strains (see Table 10):

An unexpected finding was that wTei could not fully rescue its own modification (Table 5). To our knowledge, this is the first fully documented report of a Wolbachia strain that is unable to fully rescue its own modification. Although the incomplete rescue of wCer2 and wCer4 modifications by wCer2 and wCer4 themselves in transinfected medfly lines has previously been reported in Ceratitis capitata, the presence of multiple infections in those cases could not be excluded (Zabalou et al. 2004b). Riegler et al. (2004) also reported that wCer2 cannot fully rescue its own CI, when transferred to D. simulans STCP; however, the authors concluded imperfect transmission to be the likely explanation. This is not the case in our study, since wTei exhibits perfect maternal transmission in the transinfected line of D. simulans STCP (data not shown). It is worth noting that both wYak and wSan Wolbachia strains can, with the same efficiency as wTei, partially rescue the wTei modification in the D. simulans STCP background, suggesting that all three Wolbachia strains probably share the same genetic rescue properties (see also below). It should be noted at this point that the question of which Wolbachia strains can rescue the wYak and wSan modification could not be validly addressed due to the low levels of CI induced by these strains.

The wYak, wTei, and wSan Wolbachia strains can fully rescue the wRi modification in the D. simulans STCP background, as shown in Table 6. The wYak, wTei, and wSan strains exhibited the same rescue activity as in their native host background, D. yakuba, D. teissieri, and D. santomea, respectively (Zabalou et al. 2004a). On the other hand, wRi exhibits a very low rescue activity of the wTei modification in the D. simulans STCP background, as shown in Table 5. Such asymmetrical CI relationships have been reported in the Culex pipiens–Wolbachia system (Sinkins et al. 2005) as well as for wMel and wRi (Poinsot et al. 1998). Poinsot et al. (1998) reported a unidirectional CI pattern between the two mod+ strains, wMel and wRi: wRi can fully rescue the wMel modification, while wMel can only partially rescue the wRi modification. A similar asymmetrical CI pattern was observed in our study between wTei and wRi in the same host background, D. simulans STCP: wTei can fully rescue the wRi modification while wRi can only slightly rescue the wTei modification.

-

The wYak, wTei, and wSan Wolbachia strains exhibit different compatibility relationships with the wMel strain in the D. simulans STCP background, as shown in Tables 5 and 7. The wYak and wSan strains do not rescue the wMel modification. However, the wTei strain does rescue the wMel modification, although the rescue is not complete. On the other hand, the wMel strain does not rescue the wTei modification. These data suggest the presence of another asymmetrical CI pattern, this time between wTei and wMel: wTei can partially rescue wMel while wMel cannot rescue wTei.

In addition, the data of our study allow us to discuss the compatibility relationships between wMel and wRi. Poinsot et al. (1998) could not address the question of whether the assymetrical CI relationship between wRi and wMel was qualitative or quantitative. In our study, it is demonstrated that wSan and wYak can rescue the wRi modification but not the wMel modification, suggesting that the genetic determinants of modification are qualitatively different between wMel and wRi.

As shown in Table 8, wYak, wTei, and wSan cannot rescue the wHa modification. In addition, the wHa strain cannot rescue the wTei modification, suggesting that wTei and wHa are bidirectionally incompatible. Also, the wAu strain neither induces CI in the D. simulans STCP background nor rescues the wTei modification (see Table 5), confirming once again its mod− resc− status (Hoffmann et al. 1996).

The compatibility relationships of the wYak, wTei, and wSan (A-supergroup Wolbachia strains) with two B-supergroup Wolbachia strains, wNo and wMa, were also studied (Tables 5 and 9). Our results showed that the wYak, wTei, and wSan strains do not rescue the wNo modification. On the other hand, the wNo strain can partially rescue the wTei modification. These data suggest that the Wolbachia strains wTei and wNo are bidirectionally incompatible, exhibiting a unique asymmetrical CI pattern. It should also be noted that this is the first report of a B-supergroup Wolbachia strain, the wNo, being able to rescue, if only partially, the modification induced by an A-supergroup Wolbachia strain. Similarly, and as shown in Table 5, another B-supergroup Wolbachia strain, wMa, which is considered a mod− resc+ strain (Bourtzis et al. 1998; Merçot and Poinsot 1998a,b; but see also James and Ballard 2000), was also shown to partially rescue the modification induced by wTei. Thus, both wNo and wMa are able to partially rescue the wTei modification. Given the fact that wMa fully rescues the wNo modification (Bourtzis et al. 1998; Merçot and Poinsot 1998a,b), these results further support the genetic and phylogenetic evidence that wNo and wMa are very closely related (Bourtzis et al. 1998; Merçot and Poinsot 1998a,b; James and Ballard 2000; Paraskevopoulos et al. 2006).

In conclusion, the above discussed observations suggest that wTei exhibits a unique combination of CI properties in the D. simulans STCP background: being bidirectionally incompatible with wHa, exhibiting a complex pattern of modification and rescue relationships (partial and/or complete) with both A-supergroup (wYak, wSan, wMel, and wRi) and B-supergroup (wNo and wMa) strains and at the same time being unable to fully rescue its own modification. How can such a peculiar CI pattern be explained?

Presence of multiple rescue factors in a Wolbachia strain?

A hypothesis that can explain the puzzling combination of CI properties present in the wTei strain is that this Wolbachia strain carries in its genome at least three functional rescue factors for wTei, wRi, and wMel, respectively. This conclusion is based on our genetic crosses, which clearly suggest that wTei can partially rescue wTei and fully rescue wRi, while it can only partially rescue wMel. It is also evident that the wRi strain carries at least two rescue determinants for wRi and wMel: wRi fully rescues wRi and wMel. Similarly, the wMel genome contains at least two rescue determinants for wMel and wRi: wMel fully rescues wMel and partially rescues wRi. In addition, also the wNo and wMa strains carry at least two rescue factors: (a) the first functional rescue factor is specific for wNo since both of these strains can fully rescue the wNo imprint, and (b) wNo and wMa also carry a second, less functional, rescue factor for wTei, since they can partially rescue the wTei imprint. This study clearly indicates that single Wolbachia strains can carry multiple genetic determinants for rescue functions, belonging to different CI systems. An alternative more qualitative hypothesis could also be proposed. The question is whether “generalist” rescue determinants could exist. Can the degree of specificity of the modification and rescue functions also be questioned? Since the molecular basis of CI is not known, this hypothesis cannot be excluded.

It is worth noting in this context that mosquitoes of the C. pipiens complex exhibit very complex CI patterns between populations, with a high frequency of uni- or bidirectional incompatibilities (Subbarao 1982; Magnin et al. 1987; O'neill and Paterson 1992; Guillemaud et al. 1997; Sinkins et al. 2005). Extensive studies on the wPip Wolbachia variants revealed no polymorphism in the nucleotide sequences of 16S rRNA, ftsZ and wsp genes, the only differences being restricted to the transposons and ankyrin genes (Stouthamer et al. 1993; Guillemaud et al. 1997; Duron et al. 2005; Sinkins et al. 2005). On the basis of the above studies, it is evident that the compatibility relationships of the wPip variants infecting species in the C. pipiens complex are not in accordance with a single pair of modification and rescue factors, similar to our observations described above for Drosophila; the major difference being that, while all Wolbachia strains are closely related in C. pipiens (all closely related members of B supergroup), the strains used in our study are rather divergent (members of both A and B supergroups).

Presence of multiple modification factors:

It is difficult to determine if a Wolbachia strain possesses multiple modification factors. However, in the case of wTei, the question arises. The wTei strain appears to bear three independent genetic rescue determinants (RESCTEI+, RESCRI+, and RESCMEL+). Does it also possess the corresponding Mod determinants?

The results obtained using the strain D. simulans STCP [wNo] allow an inference for the RI and MEL systems. D. simulans STCP [wNo] females are completely incompatible with D. simulans STCP [wRi] and D. simulans STCP [wMel] males. If the wTei variant does possess the functional Mod factors characterizing wRi and wMel, these D. simulans STCP [wNo] females should be completely incompatible with D. simulans STCP (wTei) males, which is not the case, the crosses being partially compatible. The negative answer is confirmed, in the case of the MEL system, by D. simulans STCP (wYak) and D. simulans STCP (wSan) females. Indeed, these females are incompatible with males from the D. simulans STCP [wMel] line but are compatible with D. simulans STCP (wTei) males. Therefore, the wTei variant seems only to express the TEI mod factors. The alternative hypothesis would be that wTei possesses the genetic Mod factors for RI and MEL but that these determinants are not expressed fully in this Wolbachia variant. However, our results do not support this possibility.

Is wTei a suicide Wolbachia variant?

As shown above, wTei can only partially rescue its own imprint. This was an unexpected finding and represents the first documented case of an, even partial, suicide Wolbachia strain reported as yet. How can this partial rescue then be explained?

There are two possible explanations: the first possible explanation is that wTei is a suicide variant in a qualitative manner; that is, it is a true suicide strain. Different mathematical approaches based on the “lock-and-key” model (Poinsot et al. 2003) suggest that new CI types can evolve through a two-step process (Charlat et al. 2001, 2005; but see also Dobson 2004 for an alternative hypothesis): the first step involves drift on the modification variants, whereas the second step involves selection on the rescue variants. Let us assume a strain that develops a new modification factor (modB) that cannot be rescued by either the wild-type (modA rescA) or the mutant strain (modB rescA). If the modB rescA mutant strain reaches a high frequency in the population, a second mutant, modB rescB, is selectively favored and replaces both the wild-type modA rescA and the first mutant, modB rescA (Charlat et al. 2001, 2005). However, it has been determined that even a very small degree of partial compatibility between the new modB and rescA function plays an important role in the likelihood of the evolution of a novel CI type (Charlat et al. 2005; Engelstädter et al. 2006). The wTei strain may represent the equivalent of such newly evolved modB rescA mutant strain.

The second possible explanation is that wTei is not a suicide variant in a qualitative way but rather in a quantitative way: too much modification factor may be expressed in D. simulans STCP (wTei) young males for the rescue function to neutralize it completely. The same kind of phenomenon can be found with other Wolbachia variants, when using very young males (Yamada et al. 2007). In the case of wTei, however, it is difficult to test this, since the CI levels expressed by wTei decrease very fast with age in D. simulans (our unpublished observations). Alternatively, the female germ line may have less rescue capacity than the one needed for the complete rescue of the wTei modification (i.e., low levels of rescue product being due to low Wolbachia density). Our study shows that the wTei distribution and infection levels in embryos, ovaries, and testes of the transinfected host D. simulans STCP (wTei) are similar to those observed in its native host D. teissieri (wTei). In addition, the wTei strain infecting D. simulans STCP females can fully rescue the modification of heavily wRi-infected D. simulans STCP males, thus, a mechanism based on density levels is not likely. However, it should also be noted that another factor, which may be influencing both the modification and the rescue functions, is the lytic state of the Wolbachia phage (WO), as recently reported by Bordenstein et al. (2006). The phage may be entering its lytic phase at a particular tissue and/or developmental stage, thus reducing the Wolbachia levels and influencing the modification and/or rescue functions in a tissue- and developmental stage-specific manner.

An alternative hypothesis could also be proposed. Even though wTei might behave as a suicide variant in D. simulans, this phenotype is not expressed in the native host where wTei does not induce CI, suggesting that the genetic determinants of CI might evolve neutrally (at least on the CI phenotype).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jacques Lagnel for sequencing the wsp gene of the transinfected D. simulans STCP lines and Denis Poinsot and Stefan Oehler for the critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments that helped to significantly improve the manuscript. This research was supported in part by a grant from the European Union (QLK3-CT2000-01079) and by intramural funding support from the University of Ioannina to K.B.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Daniel Lachaise.

References

- Baldo, L., N. Lo and J. H. Werren, 2005. Mosaic nature of the Wolbachia surface protein. J. Bacteriol. 187 5406–5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo, L., S. Bordenstein, J. J. Wernegreen and J. H. Werren, 2006. a Widespread recombination throughout Wolbachia genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23 437–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo, L., J. C. Dunning Hotopp, K. A. Jolley, S. R. Bordenstein, S. A. Biber et al., 2006. b Multilocus sequence typing system for the endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 7098–7110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandi, C., T. J. C. Anderson, C. Genchi and M. L. Blaxter, 1998. Phylogeny of Wolbachia in filarial nematodes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 265 2407–2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordenstein, S. R., and J. J. Wernegreen, 2004. Bacteriophage flux in endosymbionts (Wolbachia): infection frequency, lateral transfer, and recombination rates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21 1981–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordenstein, S. R., and J. H. Werren, 2007. Bidirectional incompatibility among divergent Wolbachia and incompatibility level differences among closely related Wolbachia in Nasonia. Heredity 99 278–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordenstein, S. R., J. J. Uy and J. H. Werren, 2003. Host genotype determines cytoplasmic incompatibility type in the haplodiploid genus Nasonia. Genetics 164 223–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordenstein, S. R., M. L. Marshall, A. J. Fry, U. Kim and J. J. Wernegreen, 2006. The tripartite associations between bacteriophage, Wolbachia, and arthropods. PLoS Pathog. 2 e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis, K., A. Nirgianaki, P. Onyango and C. Savakis, 1994. A prokaryotic dnaA sequence in Drosophila melanogaster: Wolbachia infection and cytoplasmic incompatibility among laboratory strains. Insect Mol. Biol. 3 131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis, K., A. Nirgianaki, G. Markakis and C. Savakis, 1996. Wolbachia infection and cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila species. Genetics 144 1063–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis, K., S. L. Dobson, H. R. Braig and S. L. O'Neill, 1998. Rescuing Wolbachia have been overlooked. Nature 391 852–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis, K., H. R. Braig and T. L. Karr, 2003. Cytoplasmic incompatibility, pp. 217–246 in Insect Symbiosis, edited by K. Bourtzis and T. Miller. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- Boyle, L., S. L. O'Neill, H. M. Robertson and T. L. Karr, 1993. Interspecific and intraspecific horizontal transfer of Wolbachia in Drosophila. Science 260 1796–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braig, H. R., W. Zhou, S. L. Dobson and S. L. O'Neill, 1998. Cloning and characterization of a gene encoding the major surface protein of the bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. J. Bacteriol. 180 2373–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaini, G., R. Dallai and M. G. Riparbelli, 1997. Wolbachia-induced delay of paternal chromatin condensation does not prevent maternal chromosomes from entering anaphase in incompatible crosses of Drosophila simulans. J. Cell Sci. 110 271–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlat, S., C. Calmet and H. Merçot, 2001. On the mod resc model and the evolution of Wolbachia compatibility types. Genetics 159 1415–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlat, S., K. Bourtzis and H. Merçot, 2002. a Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility, pp. 623–644 in Symbiosis: Mechanisms and Model Systems (Cellular Origin and Life in Extreme Habitats, Vol. 4), edited by J. Seckbach. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- Charlat, S., A. Nirgianaki, K. Bourtzis and H. Merçot, 2002. b Evolution of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans and D. sechellia. Evolution 56 1735–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlat, S., L. Le Chat and H. Merçot, 2003. Characterization of non-cytoplasmic incompatibility inducing Wolbachia in two continental African populations of Drosophila simulans. Heredity 90 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlat, S., M. Riegler, I. Baures, D. Poinsot, C. Stauffer et al., 2004. Incipient evolution of Wolbachia compatibility types. Evol. Int. J. Org. Evol. 58 1901–1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlat, S., C. Calmet, O. Andrieu and H. Merçot, 2005. Exploring the evolution of Wolbachia compatibility types: a simulation approach. Genetics 170 495–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. E., Z. Veneti, K. Bourtzis and T. L. Karr, 2002. The distribution and proliferation of the intracellular bacteria Wolbachia during spermatogenesis in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 111 3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. E., Z. Veneti, K. Bourtzis and T. L. Karr, 2003. Wolbachia distribution and cytoplasmic incompatibility during sperm development: the cyst as the basic cellular unit of CI expression. Mech. Dev. 120 185–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clary, D. O., and D. R. Wolstenholme, 1985. The mitochondrial DNA molecule of Drosophila yakuba: gene organization, and genetic code. J. Mol. Evol. 22 252–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, S. L., 2004. Evolution of Wolbachia cytoplasmic incompatibility types. Evolution 58 2156–2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duron, O. J. Lagnel, M. Raymond, K. Bourtzis, P. Fort et al., 2005. Transposable element polymorphism of Wolbachia in the mosquito Culex pipiens: evidence of genetic diversity, superinfection and recombination. Mol. Ecol. 14 1561–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelstädter, J., S. Charlat, A. Pomiankowski and G. D. Hurst, 2006. The evolution of cytoplasmic incompatibility types: integrating segregation, inbreeding, and outbreeding. Genetics 172 2601–2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferree, P. M., and W. Sullivan, 2006. A genetic test of the role of the maternal pronucleus in Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 173 839–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, R., S. L. O'Neill and H. M. Robertson, 1995. Wolbachia infections and the expression of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila sechellia and D. mauritiana. Genetics 140 1307–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemaud, T., N. Pasteur and F. Rousset, 1997. Contrasting levels of variability between cytoplasmic genomes and incompatibility types in the mosquito Culex pipiens. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B 264 245–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, A. A., 1988. Partial cytoplasmic incompatibility between two Australian populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 48 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, A. A., M. Turelli and G. M. Simmons, 1986. Unidirectional incompatibility between populations of Drosophila simulans. Evolution 40 692–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, A. A., D. J. Clancy and E. Merton, 1994. Cytoplasmic incompatibility in Australian populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 136 993–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, A. A., D. Clancy and J. Duncan, 1996. Naturally-occurring Wolbachia infection in Drosophila simulans that does not cause cytoplasmic incompatibility. Heredity 76 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden, P. R., P. Jones and J. F. Brookfield, 1993. Evidence for a Wolbachia symbiont in Drosophila melanogaster. Genet. Res. 62 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huigens, M. E., and R. Stouthamer, 2003. Parthenogenesis associated with Wolbachia, pp. 247–266 in Insect Symbiosis, edited by K. Bourtzis and T. Miller. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- Hurst, G. D. D., F. M. Jiggins and M. E. N. Majerus, 2003. Inherited microorganisms that selectively kill male hosts: the hidden players of insect evolution?, pp. 177–198 in Insect Symbiosis, edited by K. Bourtzis and T. Miller. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- James, A. C., and J. W. Ballard, 2000. Expression of cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila simulans and its impact on infection frequencies and distribution of Wolbachia pipientis. Evolution 54 1661–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, A. C., M. D. Dean, M. E. McMahon and J. W. Ballard, 2002. Dynamics of double and single Wolbachia infections in Drosophila simulans from New Caledonia. Heredity 88 182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiggins, F. M., J. H. von Der Schulenburg, G. D. Hurst and M. E. Majerus, 2001. Recombination confounds interpretations of Wolbachia evolution. Proc. Biol. Sci. 268 1423–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachaise, D., M. Harry, M. Solignac, F. Lemeunier, V. Benassi et al., 2000. Evolutionary novelties in islands: Drosophila santomea, a new melanogaster sister species from São Tome. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 267 1487–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartillot, N., and H. Philippe, 2004. A Bayesian mixture model for across-site heterogeneities in the amino-acid replacement process. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21 1095–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassy, C. W., and T. L. Karr, 1996. Cytological analysis of fertilization and early embryonic development in incompatible crosses of Drosophila simulans. Mech. Dev. 57 47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnin, P., N. Pasteur and M. Raymond, 1987. Multiple incompatibilities within populations of Culex pipiens L. in southern France. Genetica 74 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh, P., and J. A. Nelder, 1989. Generalized Linear Models, Ed. 2. Chapman & Hall, London.

- McGraw, E. A., and S. L. O'Neill, 1999. Evolution of Wolbachia pipientis transmission dynamics in insects. Trends Microbiol. 7 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw, E. A., D. J. Merritt, J. N. Droller and S. L. O'Neill, 2001. Wolbachia-mediated sperm modification is dependent on the host genotype in Drosophila. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 268 2565–2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merçot, H., B. Llorente, M. Jacques, A. Atlan and C. Montchamp-Moreau, 1995. Variability within the Seychelles cytoplasmic incompatibility system in Drosophila simulans. Genetics 141 1015–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merçot, H., and D. Poinsot, 1998. a … and discovered on Mount Kilimanjaro. Nature 391 853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merçot, H., and D. Poinsot, 1998. b Wolbachia transmission in a naturally bi-infected Drosophila simulans strain from New-Caledonia. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 86 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Merçot, H., and S. Charlat, 2004. Wolbachia infections in Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans: polymorphism and levels of cytoplasmic incompatibility. Genetica 120 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]