Abstract

As part of the Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium pilot project focused on small eukaryotic proteins and protein domains, we have determined the NMR structure of the protein encoded by ORF YML108W from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. YML108W belongs to one of the numerous structural proteomics targets whose biological function is unknown. Moreover, this protein does not have sequence similarity to any other protein. The NMR structure of YML108W consists of a four-stranded β-sheet with strand order 2143 and two α-helices, with an overall topology of ββαββα. Strand β1 runs parallel to β4, and β2:β1 and β4:β3 pairs are arranged in an antiparallel fashion. Although this fold belongs to the split βαβ family, it appears to be unique among this family; it is a novel arrangement of secondary structure, thereby expanding the universe of protein folds.

Keywords: Heteronuclear NMR, protein fold, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, structural proteomics

Structural proteomics is an emerging field of biological research aimed at solving the complete representative set of protein structures through the application of high-throughput structure determination techniques. The premise is that once solved, protein structures may then be used to decode the function of genes identified within a genome (Zarembinski et al. 1998; Cort et al. 2000; Yang et al. 2002). However, determination of all protein structures experimentally is not feasible because of costs and time limitations. Consequently, recent efforts have focused on the characterization of a representative fraction of all proteins (Burley and Bonanno 2002). Resources such as CATH (Orengo et al. 1997), FSSP (Holm and Sander 1999), HSSP (Schneider et al. 1997), or SCOP (Lo Conte et al. 2000) illustrate that fewer than 1000 folds and ~2500 families are representative of over 20,000 structures deposited in PDB (Berman et al. 2000). Due to the fact that the majority of similar folds have less than 12% pairwise sequence identity (Yang and Honig 2000), a target selection strategy on the basis of the determination of one structure for each unknown fold is not straightforward. A more realistic approach is to determine one structure for each family of proteins that are related by sequence (Liu and Rost 2002). Following this strategy, it is anticipated that structural proteomics efforts will help to increase our knowledge about the conformational space available to proteins. An interesting situation arises when a protein sequence can not be included in any of the protein families related by sequence.

Here, we describe the solution structure of the protein encoded by ORF YML108W from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The biological function of YML108W is unknown, and a BLAST search against all the databases did not reveal sequence similarity to any other protein or protein family. Three possible outcomes were predicted for this project: (1) YML108W would have, in spite of the absence of any sequence similarity, a previously known fold; (2) YML108W would have a new fold and define a new superfamily; or (3) YML108W would have a known fold, yet still define a new family. In fact, we find that the general architecture (split βαβ) of YML108W is quite common. However, we were unable to find any protein with the same order and configuration of secondary structure elements, so we believe YML208W defines a new subfamily of the split βαβ sandwiches.

Results and Discussion

Structure determination

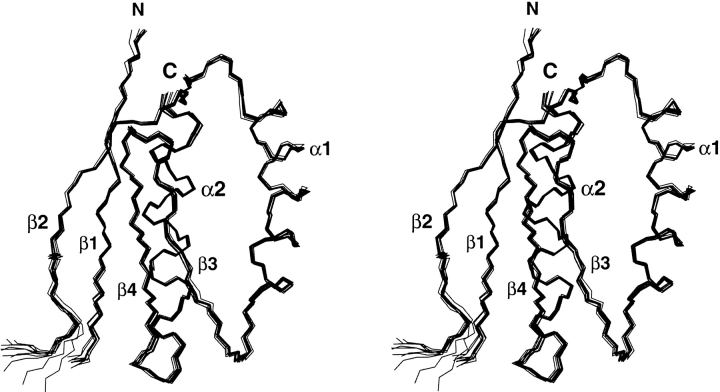

The three-dimensional structure of YML108W was determined using a torsion angle dynamics protocol from a total of 1452 NMR-derived constraints (Fig. 1 ▶; Table 1). A total of 94% of the manually picked NOE cross-peaks were retained for the final structure calculation. They correspond to reliable distance constraints that were unambiguously assigned after multiple cycles of calculations. The average global root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) values relative to the mean coordinates are 0.28 Å ± 0.10 for the backbone atoms of the residues Asn 5–Glu 14 and Lys 34–Asn 105, and 0.68 Å ± 0.15 for the heavy atoms. The loop connecting β1 and β2 within the structure ensemble shows a significant variation from the average rmsd found in the ordered regions of the protein. These differences are due to the existence of a limited number of observable constraints at those regions. Most of the residues in this loop display chemical shifts close to random coil values, intraresidue NOEs only, cross-peaks to the water resonance in a gradient water suppression 15N-edited NOESY, and no diagonal peaks. Moreover, 40% of the amide chemical shifts from this loop are undetectable in the NH-correlated heteronuclear NMR experiments, suggesting that this loop is undergoing conformational fluctuations in the intermediate exchange regime of the NMR timescale.

Figure 1.

Stereoview of the backbone (N, Cα, C′) of 10 superimposed NMR-derived structures of YML108W of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (residues 5–14 and 33–105).

Table 1.

Structural statistics for the ensemble calculated for YML108Wa

| Distant restraints | |

| All | 1452 |

| Intraresidue | 402 |

| Sequential (|i − j| = 1) | 366 |

| Medium range (2 ≤ |i − j| ≤ 4) | 320 |

| Long range (|i − j| > 4) | 364 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 39 × 2 |

| Dihedral angle restraints | |

| All | 214 |

| φ | 82 |

| ψ | 83 |

| χ1 | 49 |

| Residual target function, Å2 | 2.12 ± 0.23 |

| Residual NOE violations per structure | |

| Number > 0.1 Å | 2 ± 1 |

| Average, Å | 0.28 ± 0.05 |

| Maximum, Å | 0.38 |

| r.m.s.d. relative to the mean coordinates, Å | |

| All residuesb | |

| Backbone atoms | 0.28 ± 0.10 |

| All heavy atoms | 0.68 ± 0.15 |

| Ordered regionsc | |

| Backbone atoms | 0.16 ± 0.09 |

| All heavy atoms | 0.56 ± 0.10 |

| Ramachandran plot (%)d | |

| Residues in most favored regions | 83 |

| Residues in additional allowed regions | 14 |

| Residues in generously allowed regions | 3 |

| Residues in disallowed regions | 0 |

a Ensemble of the 10 lowest energy structures of 200 calculated.

b Rmsd values for residues 5–14 and 33–105.

c Only residues in β-strands and α-helices are included.

d Dihedral angle characteristics from CYANA.

Overall fold

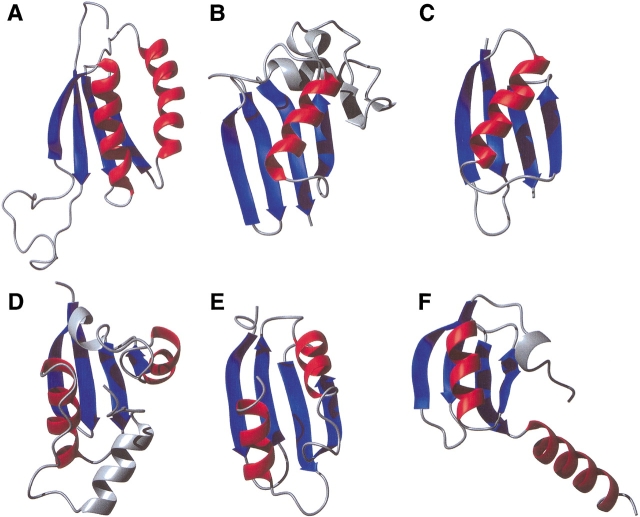

The structure of YML108W has two α-helices (Leu 50–Glu 69 and Ile 90–Asn 105) and a four-stranded β-sheet with a strand order 2143, with an overall topology ββαββα (Fig. 2A ▶). The β-sheet comprises residues Arg 8–Leu 13 (β1), Phe 37–Ile 42 (β2), Ile 72–Ser 77 (β3), and Leu 81–Leu 86 (β4). Strand β1 runs parallel to β4, and β2:β1 and β4:β3 are antiparallel. Both α-helices are located on the same side of the β-sheet and run antiparallel to each other. Long-range NOEs between the helices and the sheet established their relative orientation. The residues connecting the first two β-strands (Asp 15–Gly 32) form a large disordered loop.

Figure 2.

Ribbon diagram depicting (A) YML108W, (B) formaldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PDB accession no. 1B25), (C) B1 domain of protein G (PDB accession no. 2GB1), (D) chain E of the Cytoplasmic β Subunit-T1 Assembly Of Voltage-Dependent K Channels (PDB accession no. 1EXB), (E) carboxy-terminal domain of the Escherichia coli arginine repressor (PDB accession no. 1XXA), and (F) amino-terminal domain of the initiation factor 3 (PDB accession no. 1TIF). The common β-strands and α-helices between YML108W and the other proteins are shown in blue and in red, respectively. Insertions are shown in gray.

Structure comparison

A three-dimensional structure search using DALI (Holm and Sanders 1993) showed that YML108W shares weak structural homology (DALI Z-scores between 2.0 and 3.1; pairs with Z <2.0 are structurally dissimilar) to the α/β domains of a number of proteins. This is not surprising given the topology of YML108W (ββαββα). However, in all of the proteins but one, the two central β-strands are antiparallel. The only exception, a fragment of the formaldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PDB accession no. 1B25, Z-score 2.0), contains an insertion of two antiparallel β-strands and an α-helix between the corresponding β3 and β4 strands from YML108W, and is missing the second α-helix (Fig. 2B ▶).

An interactive analysis of the SCOP database (Lo Conte et al. 2000) and the classification of α/β folds by Orengo and Thornton (1993), reveals that the structure of YML108W resembles the β-grasp fold, the POZ domain fold (SCOP classification), and the split βαβ fold (Orengo and Thornton 1993). Thus, proteins like the B1 domain of protein G (PDB accession no. 2GB1) contain a four-stranded β-sheet, with the two central β-strands running parallel to each other, but the second α-helix is missing (Fig. 2C ▶). The chain E of the Cytoplasmic β Subunit-T1 Assembly Of Voltage-Dependent K Channels (PDB accession no. 1EXB) also contains a four-stranded β-sheet with parallel central β-strands, but there is an insertion of an extra α-helix between β2 and β3, and the packing of the α-helices is quite different from that in YML108W (Fig. 2D ▶). The structures of the carboxy-terminal domain of the Escherichia coli arginine repressor (PDB accession no. 1XXA) and YML108W are very similar, except that in the former, the two central β-strands are antiparallel (Fig. 2E ▶). Finally, we found one protein with parallel central β-strands and containing two α-helices (amino-terminal domain of the initiation factor 3; PDB accession no. 1TIF), but, in this case, the two α-helices run parallel to each other, with the second α-helix protruding from the body of the amino-terminal domain toward the carboxy-terminal domain (Fig. 2F ▶).

We believe that the structure of YML108W represents another subfamily of the split βαβ fold. This data point in protein fold space adds to the diversity of folds available to proteins and will facilitate the understanding of the relationship between sequence and three-dimensional structure.

Materials and methods

Protein purification

A recombinant protein consisting of the full sequence of YML108W (105 amino acids) was expressed in E. coli BL21-DE3 cells containing the pET-15b expression vector (Novagen). Cells were grown at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.6 and induced with 1 mM IPTG for 5 h at 25°C. The protein was purified to homogeneity using metal affinity chromatography. U-15N and U-13C,15N samples were produced in standard M9 medium supplemented with 15N ammonium chloride (1 g/L) and 13C glucose (2 g/L). 15N-labeled or 13C/15N-labeled protein solution was prepared in 25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.5), 450 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 95% H20/5% D2O. The concentration of the purified protein ranged between 1.0 and 1.5 mM.

NMR spectroscopy

All NMR spectra were recorded at 25°C on a Varian INOVA 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with pulsed-field gradient triple-resonance probes. Linear prediction was used in the 13C and 15N dimensions to improve the digital resolution. Spectra were processed using the NMRPipe software package (Delaglio et al. 1995) and analyzed with XEASY (Bartels et al. 1995). SPSCAN (Glaser and Wüthrich) was used to convert nmrPipe formatted spectra into XEASY. The assignments of the 1H, 15N, 13CO, and 13C resonances were based on the following experiments: CBCA(CO)NH, HNCACB, CC(CO)NH-TOCSY, HNCO, HNHA, 15N-edited TOCSY-HSQC, and HCCH-TOCSY (Bax et al. 1994; Kay 1997). The backbone resonance assignment was achieved mainly by the combined analysis of the HNCACB and CBCA(CO)NH data. The side-chain resonances were identified mainly by the analysis of HCCH-TOCSY. Aromatic ring resonances were assigned on the basis of the analysis of heteronuclear NOESY optimized for the detection of aromatic 13C/1H resonances. In the 1H-15N HSQC, 84% backbone amide, resonances were assigned. Of the other resonances, 96% have been assigned for Cα, 93% for Hα, and 96% for C′. Moreover, 95% aliphatic side chains have been assigned for YML108W.

Structure calculation

For structure calculation purposes, a 15N-edited and a 13C-edited NOESY-HSQC (τm = 150 msec; Kay et al. 1992, Pascal et al. 1994) were acquired. NOE cross-peak assignments were obtained by using a combination of manual and automatic procedures. An initial fold of the protein was calculated on the basis of unambiguously assigned NOEs, with subsequent use of the module CANDID within the program CYANA (Herrmann et al. 2002). CANDID/CYANA performs automated assignment and distance calibration of NOE intensities, structure calculation with torsion angle dynamics, and automatic NOE upper-distance limit violation analysis. Peak analysis of the NOESY spectra were generated by interactive peak picking with the program XEASY. Backbone dihedral restraints were derived from 1Hα and 13Cα secondary chemical shifts using TALOS (Cornilescu et al. 1999). The program MOLMOL (Koradi et al. 1996) was used to analyze the resulting 10 energy-minimized conformers and to prepare drawings of the structures.

Accession numbers

The chemical shifts have been submitted to the BMRB (accession no. 5568), and the structure ensemble and NOE constraint file has been submitted to the PDB (accession no. 1N6Z).

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Semesi, C. Liu, B. Szymczyna, and B. Wu for their technical assistance. We also thank Alexey G. Murzin for useful discussions on the structural classification of YML108W. All of the spectra were recorded at EMSL, a national scientific users facility sponsored by DOE Biological and Environmental Research, located at PNNL and operated by Battelle. This work was funded by the Ontario Research and Development Challenge Fund, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the NIH (P50 GM62413-02).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium

Article and publication are at http://www.proteinscience.org/cgi/doi/10.1110/ps.0240903.

References

- Bartels, C., Xia, T., Billeter, M., Güntert, P., and Wüthrich, K. 1995. The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR scpectral analysis of biological macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR 6 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax, A., Vuister, G.W., Grzesiek, S., Delaglio, F., Wang, A.C., Tschudin, R., and Zhu, G. 1994. Measurement of homo- and heteronuclear J couplings from quantitative J correlation. Methods Enzymol. 239 79–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman, H.M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T.N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I.N., and Bourne, P.E. 2000. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burley, S.K. and Bonanno, J.B. 2002. Structuring the universe of proteins. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 3 243–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu, G., Delaglio, F., and Bax, A. 1999. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR 13 289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cort, J.R., Yee, A., Edwards, A.M., Arrowsmith, C.H., and Kennedy, M.A. 2000. NMR structure determination and structure-based functional characterization of conserved hypothetical protein MTH1175 from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. J. Struct. Func. Genomics 1 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio, F., Grzesiek, S., Vuister, G.W., Zhu, G., Pfeifer, J., and Bax, A. 1995. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, R. and Wüthrich, K. SPSCAN (software). http://www.mol.biol.ethz.ch/wuthrich/software/spscan.

- Herrmann, T., Güntert, P, and Wüthrich, K. 2002. Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE assignment using the new software CANDID and the torsion angle dynamics algorithm DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 319 209–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm, L. and Sander, C. 1993. Protein structure comparison by alignment of distance matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 233 123–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ———. 1999. Protein folds and families: Sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 27 244–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, L.E. 1997. NMR methods for the study of protein structure and dynamics. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 75 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay, L.E., Keifer, P., and Saarinen, T. 1992. Pure absorption gradient enhanced heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy with improved sensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 10663–10665. [Google Scholar]

- Koradi, R., Billeter, M., and Wüthrich, K. 1996. MOLMOL: A program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. and Rost, B. 2002. Target space for structural genomics revisited. Bioinformatics 18 922–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Conte, L., Ailey, B., Hubbard, T.J., Brenner, S.E., Murzin, A.G., and Chothia, C. 2000. SCOP: A structural classification of proteins database. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 257–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orengo, C.A. and Thornton, J.M. 1993. α plus β folds revisited: Some favoured motifs. Structure 1 105–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orengo, C.A., Michie, A.D., Jones, S., Jones, D.T., Swindells, M.B., and Thornton, J.M. 1997. CATH—a hierarchic classification of protein domain structures. Structure 5 1093–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascal, S.M., Muhandiram, D.R., Yamazaki, T., Forman-Kay, J.D., and Kay, L.E. 1994. Simultaneous acquisition of 15N-edited and 13C-edited NOE spectra of proteins dissolved in H2O. J. Magn. Reson. B. 103 197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, R., de Daruvar, A., and Sander, C. 1997. The HSSP database of protein structure-sequence alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 226–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, A.S. and Honig, B. 2000. An integrated approach to the analysis and modeling of protein sequences and structures. III. A comparative study of sequence conservation in protein structural families using multiple structural alignments. J. Mol. Biol. 301 679–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z., Savchenko, A., Yakunin, A., Zhang, R., Edwards, A., Arrowsmith, C.H., and Tong, L. 2002. Aspartate dehydrogenase, a novel enzyme identified from structural and functional studies of TM1643. J. Biol. Chem. [online ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zarembinski, T.I., Hung, L.W., Mueller-Dieckmann, H.J., Kim, K.K., Yokota, H., Kim, R., and Kim, S.H. 1998. Structure-based assignment of the biochemical function of a hypothetical protein: A test case of structural genomics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 95 189–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]