Abstract

The optic nerve offers a number of advantages for investigating mechanisms that govern axon regeneration in the CNS. Although mature retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) normally show no ability to regenerate injured axons through the optic nerve, this situation can be partially reversed by inducing an inflammatory response in the eye. The secretion of a previously unknown growth factor, oncomodulin, along with co-factors, causes RGCs to undergo dramatic changes in gene expression and regenerate lengthy axons into the highly myelinated optic nerve. By themselves, strategies that counteract inhibitory signals associated with myelin and the glial scar are insufficient to promote extensive regeneration in this system. However, combinatorial treatments that activate neurons' intrinsic growth state and overcome inhibitory signals result in dramatic axon regeneration in vivo. Because of the ease of introducing trophic factors, soluble receptors, drugs, or viruses expressing any gene or small interfering RNA of interest into RGCs, this system is ideal for identifying intracellular signaling pathways, transcriptional cascades, and ligand-receptor interactions that enable axon regeneration to occur in the CNS and to develop means to augment this process.

Introduction

The normal functioning of the nervous system relies upon an intricate and precise pattern of connections among many billions of nerve cells. Following injury to the mature central nervous system (CNS), damaged axons can not regenerate over any significant distance. In addition, neurons that remain unaffected by injury have only a limited ability to form new connections to compensate for ones that have been lost. Some neural replacement occurs from endogenous precursors after brain injury, but the extent of this is small (43, 52, 71). For these reasons, victims of traumatic brain injury, stroke, or certain neurodegenerative diseases are commonly left with disabilities in perception, movement, cognition and/or autonomic functioning that can be devastating and permanent.

The optic nerve as a model system

The optic nerve represents a classic instance of a CNS pathway that does not regenerate after injury. Developmentally, the retina buds from the diencephalon and the axons that arise from its projection neurons, the retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), are myelinated by brain-derived oligodendrocytes (73). If injured, RGC axons show only a transitory sprouting response but no long-distance regeneration through the optic nerve (81). As far back as 1911, however, Cajal's student, Tello, discovered that some RGCs can extend axons into a peripheral nerve graft sutured to the cut end of the optic nerve (81). This anecdotal observation provided the first piece of evidence that mature CNS neurons retain some capacity to regenerate their axons. Almost 60 years passed before more systematic experiments validated and extended these findings. Aguayo and his colleagues showed that up to 5% of RGCs can regenerate their axons over relatively great distances through a peripheral nerve graft, and even form synapses if the distal end of the graft is directed into the superior colliculus (1, 2, 95, 101). Parallel studies in other parts of the brain, including in the spinal cord, showed a similar growth potential in other neural populations (21, 82).

The extracellular environment of the mature CNS is highly suppressive to growth, particularly myelin (13, 87, 88), the perineuronal net (79), and following injury, the scar that forms (22, 60, 83, 93). For this reason, most investigators attributed the results of the grafting experiments to the more permissive environment of the peripheral nervous system vs. the CNS environment. However, other studies found that implanting a fragment of peripheral nerve into the vitreous was enough to enhance the growth potential of RGCs. Such implants caused RGCs to increase expression of the growth-associated protein GAP-43, sprout axon-like processes within the eye (16, 67), increase their ability to regenerate axons through a peripheral nerve graft (44), and most surprisingly, regenerate axons through the optic nerve itself (9). Thus, in addition to providing a more permissive substrate for growth than the CNS, these implants appear to secrete growth-promoting factors.

Macrophage activation promotes axon regeneration

What are the growth-promoting factors released from the peripheral nerve grafts and which cells produce them? In testing one candidate growth factor, our lab (50), as well as Fischer et al. (26, 27) discovered that simply injuring the lens was sufficient to cause RGCs to regenerate lengthy axons through the optic nerve or a peripheral nerve graft. We found that lens injury was associated with an influx of activated macrophages into the eye (50). An earlier study had reported that introducing activated macrophages into the rat optic nerve enhanced the survival or regeneration of RGC axons (46), and we therefore tested whether macrophage activation would be sufficient to cause extensive axon regeneration. Using the pro-inflammatory agent Zymosan, we found that macrophage activation caused even more regeneration than lens injury or a peripheral nerve implant; Zymosan also greatly augmented axon regeneration through a peripheral nerve graft (50, 108). Interestingly, the peripheral nerve implants which had earlier been shown to promote axon regeneration in the optic nerve (9) contained numerous macrophages as a result of leaving the nerve in situ for a week before grafting, and it is possible that this was responsible for the axon-promoting effects of the implants. It remains possible, however, that additional factors derived from Schwann cells or other elements in the grafts may have played a role. The effect of intravitreal macrophage activation on axon regeneration has since been confirmed in a variety of species (54, 72, 78), and probably accounts for an earlier observation that intraocular injections by themselves enhance RGC survival after axotomy (58). In another paradigm, macrophage activation within dorsal root ganglia was found to promote the ability of peripheral sensory neurons to regenerate their centrally directed processes through the dorsal roots (56, 97). Thus, under certain circumstances, inflammation can produce factors that strongly promote CNS regeneration.

Identification of the factors that promote optic nerve regeneration

What factors enable RGCs to regenerate axons into the optic nerve? One factor mannose, a simple carbohydrate that is a normal constituent of the eye. Lower vertebrates regenerate their axons spontaneously after injury. To understand the basis of this phenomenon, we investigated whether any extracellular factors present in the visual system could stimulate dissociated goldfish RGCs to extend axons in culture. Media conditioned by goldfish optic nerve glia was found to have strong axon-promoting activity, and after size-exclusion chromatography, we found that this activity was associated with a small factor of ca. 200 Da (89, 90). Surprisingly, a molecule with similar biophysical properties was found to be abundant in the rat vitreous and enabled rat RGCs to regenerate lengthy axons in culture; this growth required elevation of intracellular cAMP levels. Upon purification and analysis by mass spectrometry, this factor proved to be mannose, a simple hexose sugar that is abundant in the vitreous (51). Mannose is not sufficient to cause RGCs to regenerate injured axons into the optic nerve, however, even if intracellular cAMP levels are elevated (19, 64, 109). This observation suggests that inflammatory cells must provide an additional factor(s) to trigger extensive regeneration in vivo.

To identify the growth factor(s) involved, we collected proteins secreted by a macrophage cell line and, after chromatography, tested column fractions for biological activity. Whereas most protein fractions proved to be cytotoxic to RGCs, fractions in the range 10-20 kDa strongly enhanced outgrowth (108). Mass spec revealed that the proteins in this fraction included an evolutionarily conserved, 12 kDa Ca2+-binding protein, oncomodulin. Further studies showed that oncomodulin is secreted by inflammatory cells and binds to a cell surface receptor on RGCs with high specificity and affinity (kD ∼ 30 nM). In the presence of mannose and forskolin, oncomodulin elicited more extensive outgrowth than other well established growth factors in culture (e.g., BDNF, CNTF, GDNF) and as much outgrowth as total macrophage conditioned media. In addition, when oncomodulin was immune-depleted from macrophage-conditioned media, little axon-promoting activity remained. Most strikingly, in the presence of an agent to elevate intracellular cAMP, oncomodulin stimulated extensive axon regeneration in the mature optic nerve (Fig. 1). Thus oncomodulin is a novel, potent growth-promoting factor for optic nerve regeneration. However, it is likely that additional factors contribute to the survival and regenerative capacity of RGCs that is seen after lens injury or Zymosan-induced macrophage activation (109). Lentiviral delivery of CNTF also enables RGCs to regenerate injured axons into the optic nerve (47), as does a mixture of several other growth factors (53). However, it is not yet known whether these latter factors act directly on RGCs or through another type of cell as an intermediary.

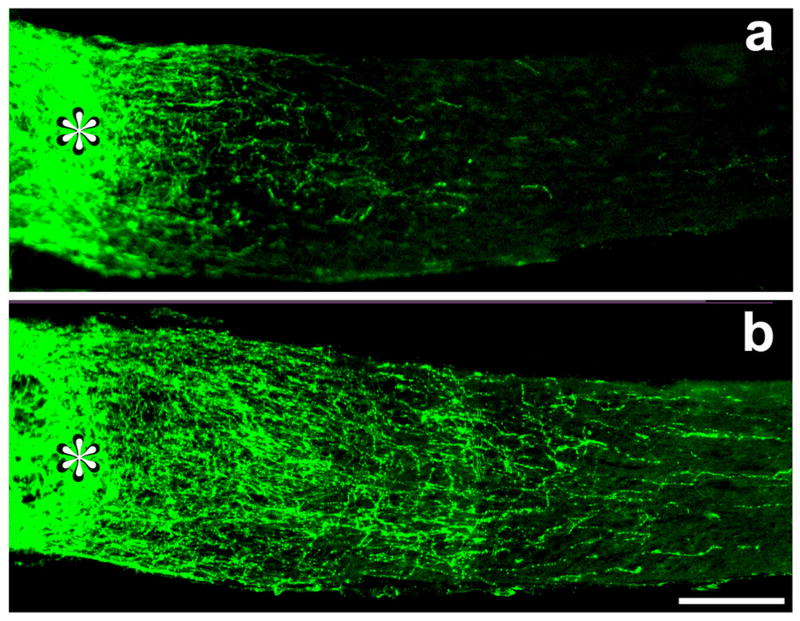

Figure 1. Oncomodulin promotes optic nerve regeneration.

Longitudinal sections of the mature rat optic nerve distal to the site of a crush injury (asterisk). Regenerating axons are visualized using an antibody to GAP-43. a: RGCs normally show no capacity to regenerate axons beyond the injury site (see Fig. 2a); intravitreal injection of polymeric microspheres causes a mild inflammatory response and stimulates a modest amount of regeneration. b: Extensive regeneration occurs when microspheres release oncomodulin and a cAMP analog. Scale bar, 250 μm (109).

Inhibitory signals limit optic nerve regeneration

As mentioned earlier, proteins associated with CNS myelin, the perineuronal net, and the scar that forms at an injury site all limit axon regeneration in the CNS. Three myelin proteins, NogoA, Myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) (61, 66), and Oligodendrocyte-myelin glycoprotein (OMgp) (105) inhibit axon growth via a receptor complex that consists of the Nogo receptor (NgR), Lingo (63) and either p75 (104) or TROY (75). Part of the NogoA signal is also conveyed through an as yet unidentified receptor (70, 105), and MAG seems to exert its effects through NgR2 and gangliosides (100). Proteoglycans are major inhibitors of axon growth within the perineuronal net and are strongly upregulated in the scar tissue that forms after injury (93). In addition to these molecules, several proteins that repel axons from inappropriate areas during development are upregulated in the mature CNS, and may also contribute to growth inhibition. Among these repellants are Ephrin-B3 (8), semaphorins 5A and 4D (30, 65), and netrin-1 (24, 57), which are expressed by oligodendrocytes; and Sema3A (40) and Slit-1 (32), which are expressed in the glial scar.

Counteracting inhibitory signaling is not sufficient to produce extensive axon regeneration in the optic nerve. One strategy to overcome inhibition in the optic nerve has been to block the activity of Nogo using an anti-NogoA antibody (18, 106) or by expressing a dominant-negative form of the Nogo receptor (NgRd-n) in RGCs (25). A more comprehensive way to overcome inhibitory signals is to interfere with RhoA. RhoA is a small GTPase that is part of the intracellular signaling pathway through which multiple inhibitors cause growth cone collapse and arrest axon growth (3, 29, 68, 69, 91). RhoA activity can be blocked with C3 ribosyltransferase, an enzyme that irreversibly ribosylates RhoA. In one study, C3 ribosyltransferase fused to a membrane-permeable sequence was applied directly to the cut end of axons (49); in another, adeno-associated viruses were used to transfect RGCs with a gene encoding C3 transferase (28). These approaches resulted in only a small amount axon regeneration into an optic nerve, though blocking RhoA has more striking effects on axon regeneration through a peripheral nerve graft (36). Another general approach to blocking inhibitory signals has been to deliver membrane-permeable analogs of cAMP into the optic nerve or eye (19, 64, 109), based on the fact that elevated cAMP enables growth cones to overcome some, though not all, inhibitory signals (96). Elevating cAMP by itself, like blocking RhoA, had only a modest effect on axon regeneration through the optic nerve or through a peripheral nerve graft (19, 64, 109).

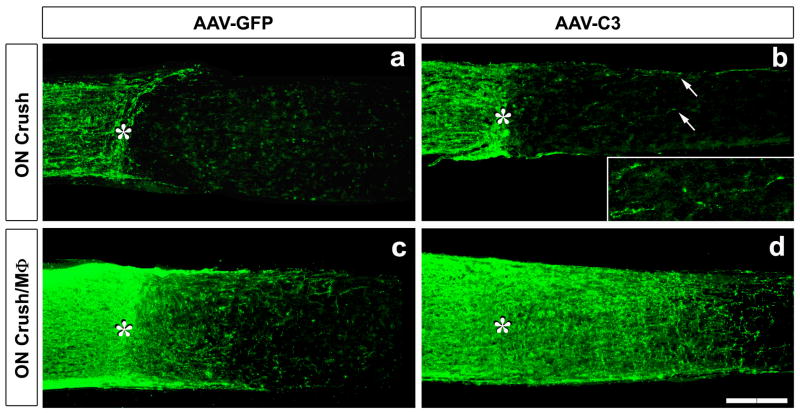

One plausible reason these approaches failed to produce extensive regeneration is that overcoming some inhibitors, or even most, would still leave other ones in place. Another possible reason, however, is that even if all inhibitory signals were overcome, the parent neurons would need to be in a growth-enabled state. To investigate whether activation of neurons' intrinsic growth state potentiates the effects of overcoming inhibitory signals, we used a gene therapy approach. Adeno-associated viruses (AAV-2) were used to transfect RGCs with genes expressing either NgRd-n or C3 ribosyltransferase. Under baseline conditions, expression of NgRd-n caused very little growth, and expression of C3 ribosyltransferase caused some growth, though not much. However, when RGCs' intrinsic growth state was activated at the same time, the amount of regeneration obtained was dramatic. Expression of NgRd-n enhanced the effect of activating RGCs' growth state 3-fold (25), whereas expression of C3 ribosyltransferase enhanced regeneration 5-fold (28) (Fig. 2). One objection to these studies is that, in the absence of an inflammatory reaction in the eye, RGCs begin to undergo apoptosis, and the ones that remain alive may not be healthy enough to extend axons. However, even when retinas were explanted in culture at an early time point when all RGCs were healthy, expression of NgRd-n or C3 transferase did not enable RGCs to extend axons on inhibitory substrates unless RGCs' intrinsic growth state had been activated prior to being explanted (25). The combination of CNTF, a cAMP analog, and a membrane-permeable form of C3 ribosyltransferase significantly enhanced RGC axon regeneration into a peripheral nerve graft above the level induced by any one or two of these factors, allowing more than 50% of surviving RGCs to extend axons for 2 cm (36). Thus, dramatic regeneration in vivo requires both activation of RGCs' intrinsic growth state and methods to counteract inhibitory signals.

Figure 2. Combinatorial treatments cause dramatic axon regeneration in the optic nerve.

(a-d) GAP- 43-positive axons visualized in longitudinal sections through the optic nerve 2 wks after optic nerve (ON) crush with (b,d) or without (a,c) intravitreal macrophage activation (MΦ) (asterisk: injury site). RGCs were transfected with AAV expressing GFP alone (a,c) or C3 ribosyltransferase + GFP (b,d). (a) No regeneration is seen after ON crush. (b) Expression of C3 ribosyltransferase stimulates modest regeneration (seen in inset, showing regenerating axons at increased magnification and illumination). (c) Intravitreal macrophage activation alone increases axon regeneration. (d) Intravitreal macrophage activation combined with C3 expression causes dramatic regeneration through the injury site and beyond. Scale bar, 200 μm.

Other examples of combinatorial treatments

As mentioned earlier, activation of macrophages in peripheral ganglia enhances the ability of sensory neurons to extend their centrally directed axons through the dorsal roots (56). A more recent study has used this approach in combination with chondroitinase ABC, an enzyme that deglycosylates and thereby blocks the inhibitory effects of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans on axon growth. As in the optic nerve, activation of peripheral neurons' growth state combined with chondroitinase ABC treatment gave far greater regeneration though the CNS environment than either approach alone, and even restored functional circuitry within the spinal cord (97). Similarly, Schwab's lab had earlier reported that the neurotrophin NT3, presumably by activating the growth potential of cortical layer 5 pyramidal cells, augmented the amount of corticospinal tract regeneration obtained using the IN-1 antibody to the myelin-associated inhibitor, NogoA (85).

The purine-sensitive kinase Mst3b regulates axon growth

Several observations over the years had suggested that axon outgrowth depends upon a purine nucleoside-sensitive pathway. Inosine, a purine nucleoside, stimulates axon outgrowth from superior cervical ganglion neurons (112), goldfish retinal ganglion cells (6), and embryonic cortical neurons (37). This activity is not mediated through purinergic receptors nor is it shared by adenosine, the precursor of inosine, but involves a direct effect upon an intracellular target (6). In contrast to the effects of inosine, certain purine nucleoside analogs block axon outgrowth. 6-thioguanine blocks the neurite-promoting effects of nerve growth factor (NGF) on peripheral ganglionic neurons and on pheochromocytoma PC12 cells (31, 103). This blockade was paralleled by the inhibition of an unknown 45-50 kDa serine-threonine kinase (4, 102, 103). This observation suggested that the 6TG-sensitive kinase might be an important part of the cell signaling pathway that controls outgrowth, and that inosine might stimulate growth by activating this same kinase. This latter possibility was borne out by studies showing that, whereas 6TG blocks the effects of various polypeptide growth factors noncompetitively, inosine competitively reverses the inhibitory effects of 6TG (6).

To isolate the growth factor- and purine-sensitive kinase, we took advantage of the ability of 6-TG to block its activity. Following multiple stages of column chromatography, the purified kinase, when sequenced, proved to be Mst3b (37). Mst3b is a neuron-specific homolog of Ste20, a kinase that controls budding in yeast. In primary neurons and PC12 cells, Mst3b is rapidly activated by growth factors; blocking its activity (with a dominant-negative form of the kinase) or its expression (using shRNAs) prevents neurons from forming axons in response to growth factors (37).

Indirect evidence suggests that Mst3b controls axon outgrowth in retinal ganglion cells. 6-TG completely blocks the axon-promoting effects of oncomodulin, mannose and elevated cAMP in cultured rat RGCs (unpublished observations). Another growth factor that stimulates RGCs to extend axons is CNTF (6, 38); the effect of CNTF on rat RGCs requires elevation of intracellular cAMP and is not as strong as that of oncomodulin (109). 6-TG blocks these effects as well (38). Preliminary studies using shRNAs provide more direct evidence that Mst3b mediates axon outgrowth in RGCs (B. Lorber, M. Howe, L. Benowitz, N. Irwin, unpublished observations).

Other molecular changes underlying RGC axon regeneration in vivo

Thus far, we have discussed some of the extrinsic signals that stimulate RGCs to regenerate their axons and one element in the signal transduction pathway linking the action of these signals to axon outgrowth. There is a great deal more to be learned, however, about the molecular events that underlie regeneration in this system. We do not know, for example, the receptors through which mannose or oncomodulin exert their effects, the signal transduction elements that lie upstream and downstream from Mst3b, or the key downstream changes in gene expression required for regeneration to occur. In RGC cultures, the effects of oncomodulin can be blocked by KN93, an inhibitor of Ca2+-calmodulin kinases, though not by inhibitors of MAP kinase kinases (MEKs) -1, -2 or -5, PI3 kinase, or Janus kinases (109), the signaling pathways utilized by neurotrophins and chemokines of the LIF/CNTF family. The latter findings accord well with the observation that the effect of lens injury on RGC outgrowth in culture is not blocked by an inhibitor of trk receptors or by an antibody to the LIF/CNTF receptor (55). Moreover, in vivo, inhibitors of MAP kinase, PI3 kinase and Jak/STAT pathways do not diminish RGC axon regeneration through a peripheral nerve graft (76).

In peripheral neurons, there is good evidence for local control of mRNA translation in the axon following nerve injury. Components of a signaling complex, which includes the importins, vimentin, dynein and Erk-1 and −2, are synthesized and assembled in the axon after injury and are transported back to the soma to inform the cell of the state of its terminals (33, 77). A good deal more remains to be learned about how such retrograde signaling pathways might integrate with pathways activated by trophic factors, acting either at the soma or retrogradely transported back to the soma, to put a neuron into an active growth state. We also do not know yet whether such retrograde signaling is required to activate axon regeneration in the optic nerve.

Axon regeneration involves changes in neuronal gene expression, raising the question of what transcriptional events might underlie these changes. In the optic nerve, c-Jun is induced after axotomy irrespective of whether RGCs successfully regenerate their axons (35, 84). Deleting the c-jun gene retards, but does not block, peripheral nerve regeneration (80). In contrast to c-Jun, the transcription factor ATF-3 is upregulated in DRG neurons selectively when the peripheral branch, which can regenerate, has been injured, but not when there is injury to dorsal roots; ATF-3 overexpression enhances axon outgrowth (92). In RGCs, ATF-3 is upregulated following axonal injury regardless of whether cells are stimulated to regenerate their axons (28). In short, transcriptional control of axon regeneration, like the related area of signal transduction, requires more study.

The prototype of a protein that is upregulated in RGCs undergoing axon regeneration is GAP-43. GAP-43 is a protein kinase C substrate that is concentrated in growing axons, growth cones, and plastic synapses in association with lipid rafts and the actin cytoskeleton (7, 23, 28, 34, 45, 62, 84, 94). A more recent microarray study has identified many other proteins that are upregulated in RGCs during regeneration (Table 1). Some of these are upregulated after axonal injury alone, whereas a relatively small number are differentially upregulated when RGCs are stimulated to regenerate their axons via macrophage activation (28). Interestingly, the pattern of molecular changes seen in RGCs stimulated to regenerate their axons bears a striking resemblance to that found in DRG neurons during peripheral nerve regeneration (10, 17, 28). This finding suggests that, when properly stimulated, RGCs can go into as strong a regenerative state as neurons of the PNS. We do not yet know whether this is true for other CNS neurons.

Table 1. Changes in RGC gene expression during axon regeneration.

| Name/function | Regenerating | Axotomy alone | Affymetrix Probe set |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPRR1 (axon growth, cytoskeleton)* | 6297 | 1912 | 1371248_at |

| C/EBP-δ (transcription)* | 26.5 | 5.5 | 1387343_at |

| cysteine-rich protein 3/LIM | 14.3 | 8.3 | 1398243_at |

| SOCS-3 (cytokine signaling) | 11.5 | 1.6 | 1377092_at |

| lipocalin 2 | 10.4 | 7.0 | 1387011_at |

| sphingosine kinase 1 | 9.4 | 1.6 | 1368254a_at |

| GAP-43 (axon growth, plasticity)* | 9.3 | 2.9 | 1367930_at |

| 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvic acid dioxygenase | 7.3 | 1.8 | 1368188_at |

| Galanin (neuropeptide) | 7.1 | 2.9 | 1387088_at |

| HSP 27 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 1367577_at |

| retinoic acid binding protein 2 | 6.6 | 4.9 | 1370391_at |

| GADD45-γ | 6.0 | 3.7 | 1388792_at |

| iGb3 synthase | 5.6 | 1.8 | 1370561_at |

| MAFK | 5.3 | 6.9 | 1372211_at |

| GADD 45-α | 5.3 | 4.8 | 1368947_at |

| Best5 | 4.9 | 1.3 | 1370913_at |

| Metallothionein | 4.7 | 2.9 | 1371237a_at |

| ATF 3 (transcription) | 4.6 | 4.1 | 1369268_at |

| Retinol-binding protein 1 | 4.6 | 2.0 | 1367939_at |

| GFAP | 4.5 | 1.7 | 1368353_at |

| Fn14 (FGF-regulated protein 2) | 4.5 | 5.0 | 1371785_at |

| ATP-binding cassette subfamily B (MDR/TAP)-1A | 4.4 | 5.7 | 1370464_at |

| serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor, G-1 | 4.4 | 1.7 | 1372254_at |

| Myxovirus (influenza virus) resistance 3 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 1387283_at |

| ASCT2 (Na+-dependent aa transporter) | 4.3 | 2.4 | 1371040_at |

| tumor-associated glycoprotein pE4 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 1370177_at |

| Importin β-3 (Karyopherin β-3 subunit) | 4.3 | 2.5 | 1373955_at |

| lysozyme | 4.2 | 2.8 | 1370154_at |

| anthrax toxin receptor 2 | 4.1 | 3.3 | 1389017_at |

| tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 1367712_at |

| Interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF-7) | 4.0 | 1.3 | 1383564_at |

| cytochrome c oxidase, subunit VIa, polypeptide 2 | 3.9 | 5.0 | 1367782_at |

| endothelin converting enzyme-like 1 | 3.9 | 4.3 | 1368923_at |

| glycoprotein (transmembrane) nmb | 3.8 | 4.8 | 1368187_at |

| Small cell adhesion glycoprotein (smagp) | 3.7 | 1.6 | 1372734_at |

| Galectin 3 | 3.7 | 6.4 | 1386879_at |

| Heme oxygenase | 3.7 | 3.3 | 1370080_at |

| moesin | 3.6 | 3.9 | 1371575_at |

| syntenin | 3.6 | 3.9 | 1376973_at |

| kinesin family member 22 | 3.6 | 2.6 | 1372516_at |

| C/EBP-β (transcription)* | 3.5 | 4.4 | 1387087_at |

| CD24 antigen | 3.5 | 3.9 | 1369953a_at |

| protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-rec., type 5 | 3.4 | 1.6 | 1368421_at |

| endothelial monocyte-activating polypeptide | 3.3 | 2.2 | 1375170_at |

| Kidney predominant protein NCU-G1 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 1371946_at |

| Serine protease inhibitor | 3.2 | 1.0 | 1368224_at |

| CREM | 3.2 | 1.8 | 1369737_at |

| cell death activator CIDE-A | 3.1 | 2.4 | 1389179_at |

Entries represent fold-increase in mRNA compared to levels in control RGCs.

Results based upon quantitative real-time PCR. Entries in bold type represent genes reported to be upregulated during axon regeneration in the peripheral nervous system.

Rewiring the brain after spinal cord injury and stroke

The possibility that mature CNS neurons can be transformed to an active growth state provides a potential strategy for improving outcome after brain injury. Some degree of dendritic (39, 98) and axonal (12, 20) sprouting occurs spontaneously in undamaged neurons following a stroke, and this can be augmented using trophic factors (41, 42). In addition, spontaneous axonal rewiring has been described in the corticospinal tract after spinal cord injury (107). Because inosine can stimulate Mst3b and promote axon outgrowth in certain types of neurons, we investigated whether it would promote the rewiring of brain connections after spinal cord injury or stroke. The rat corticospinal tract (CST) arises in layer 5 pyramidal cells of the sensorimotor cortex and projects, among other places, to the contralateral cervical and lumbar spinal cord. This pathway is important for voluntary, skilled use of the limbs, paws, and digits. Following a transection of this tract on one side of the brain or following a unilateral stroke, inosine stimulated layer 5 pyramidal cells on the undamaged side of the brain to sprout axon collaterals into the side of the spinal cord which had lost its normal innervation (5, 14), and this was accompanied by significant gains in volitional use of the affected paw (14).

An alternative strategy for improving function after stroke or spinal cord injury has been to use antibodies, inhibitory peptides, or genetic approaches to counteract inhibitory signals associated with myelin and/or the glial scar. In stroke models in rats and mice, immunological interference with NogoA, use of a soluble “decoy” receptor, or deleting the genes that encode these also promote the crossing of CST fibers from the undamaged hemisphere to the denervated side of the spinal cord (11, 48, 74). The same strain of genetically altered mice that shows CST sprouting after stroke shows relatively little regeneration of CST axons beyond the site of a spinal cord injury (110, 111), suggesting that collateral sprouting occurs more readily than long-distance regeneration in the corticospinal tract. Shorter-range sprouting can lead to the formation of new circuits that subserve functional improvements (86), and is therefore of great potential value for functional recovery. It will be important to see whether combining strategies to activate neurons' intrinsic growth state with strategies to counteract inhibitory signaling will be beneficial for the treatment of stroke and spinal cord injury.

Summary and Conclusions

The optic nerve is probably the most tractable system for investigating factors that determine the success or failure of axons to regenerate in the mammalian CNS. Axons in the optic nerve arise from a single cell population, the retinal ganglion cells, and these cells can be experimentally manipulated with minimal surgery. The vitreous can serve as a reservoir for introducing growth factors, engineered cells, drugs, or viruses with tropism for RGCs, e.g., AAV2 (15, 59) or lentivirus (99). Using this strategy, it is relatively simple to introduce any gene of interest into RGCs or to knock down the expression of any gene using an shRNA approach. As some of the studies described in this chapter illustrate, RGCs can be transformed to express particular growth factors, receptors, signaling molecules, dominant-negative forms of proteins, or shRNAs that block gene expression. This opens up the possibility of studying the molecular signals that govern CNS regeneration in an expeditious manner. We have found that the same viral vectors that transfect RGCs efficiently can also be used to transfect cortical neurons, thus making it possible to use similar strategies for studying CST regeneration or sprouting.

RGCs can regenerate lengthy axons through a peripheral nerve graft, though the percentage of cells that do so is small; however, this growth can be strongly enhanced by causing an inflammatory reaction in the eye or by using defined trophic factors. Moreover, RGCs can be stimulated to regenerate their axons through the native environment of the optic nerve. This regeneration can be stimulated by implanting a fragment of peripheral nerve into the vitreous (9), injuring the lens (50) or injecting zymosan (108), all of which introduce inflammatory cells into the eye. Macrophages secrete the protein oncomodulin, which, in the presence of agents that elevate intracellular cAMP, causes nearly as much regeneration as lens injury or zymosan (109). Another essential component of this growth is mannose, a normal constituent of the vitreous (51). Far more impressive regeneration is seen when intravitreal inflammation is combined with strategies to counteract inhibitory signals associated with myelin and the glial scar (25, 28). However, overcoming inhibition alone is insufficient to cause extensive regeneration when neurons' intrinsic growth state has not been activated. Microarray analyses point to multiple genes that contribute to the regenerative state of RGCs (28), and the functions of most of these remain to be determined. Besides knowing that Mst3b and CaM kinase II are involved in axon outgrowth, we know relatively little about the intracellular signaling pathways and transcriptional cascades that are required to activate RGCs' genetic program for growth. The relative ease of manipulating gene expression in RGCs opens up the possibility of answering many of these questions. Finally, we know a great deal about axon guidance and topography in the retino-collicular and retino-thalamic projection, and if we succeed in promoting axon regeneration beyond current levels, this system will be ideal for studying whether mature CNS neurons can reestablish topographically organized, functional connections with the appropriate targets. It is likely that both the details of what we learn about CNS regeneration in the optic nerve and the methods developed for studying these questions will have relevance for other parts of the CNS.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the agencies that supported research from our lab described herein, including the NIH (EY05690), Boston Life Sciences, Inc., Patterson Family Trust, The Glaucoma Research Foundation, and the Adelson Foundation for Medical Research. We would also like to acknowledge the technical support of the DDRC core (NIH P30 HD018655).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aguayo AJ, Rasminsky M, Bray GM, Carbonetto S, McKerracher L, Villegas-Perez MP, Vidal-Sanz M, Carter DA. Degenerative and regenerative responses of injured neurons in the central nervous system of adult mammals. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London - Series B: Biological Sciences. 1991;331:337–343. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1991.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguayo AJ, Vidal-Sanz M, Villegas-Perez MP, Bray GM. Growth and connectivity of axotomized retinal neurons in adult rats with optic nerves substituted by PNS grafts linking the eye and the midbrain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1987;495:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb23661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed Z, Dent RG, Suggate EL, Barrett LB, Seabright RJ, Berry M, Logan A. Disinhibition of neurotrophin-induced dorsal root ganglion cell neurite outgrowth on CNS myelin by siRNA-mediated knockdown of NgR, p75NTR and Rho-A. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:509–523. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batistatou A, Volonte C, Greene LA. Nerve growth factor employs multiple pathways to induce primary response genes in PC12 cells. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1992;3:363–371. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.3.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benowitz LI, Goldberg DE, Madsen JR, Soni D, Irwin N. Inosine stimulates extensive axon collateral growth in the rat corticospinal tract after injury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96:13486–13490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benowitz LI, Jing Y, Tabibiazar R, Jo SA, Petrausch B, Stuermer CA, Rosenberg PA, Irwin N. Axon outgrowth is regulated by an intracellular purine-sensitive mechanism in retinal ganglion cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29626–29634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benowitz LI, Yoon MG, Lewis ER. Transported proteins in the regenerating optic nerve: regulation by interactions with the optic tectum. Science. 1983b;222:185–188. doi: 10.1126/science.6194562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson MD, Romero MI, Lush ME, Lu QR, Henkemeyer M, Parada LF. Ephrin-B3 is a myelin-based inhibitor of neurite outgrowth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10694–10699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504021102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry M, Carlile J, Hunter A. Peripheral nerve explants grafted into the vitreous body of the eye promote the regeneration of retinal ganglion cell axons severed in the optic nerve. Journal of Neurocytology. 1996;25:147–170. doi: 10.1007/BF02284793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonilla IE, Tanabe K, Strittmatter SM. Small proline-rich repeat protein 1A is expressed by axotomized neurons and promotes axonal outgrowth. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1303–1315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01303.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cafferty WB, Strittmatter SM. The Nogo-Nogo receptor pathway limits a spectrum of adult CNS axonal growth. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12242–12250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3827-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmichael ST, Wei L, Rovainen CM, Woolsey TA. New patterns of intracortical projections after focal cortical stroke. Neurobiol Dis. 2001;8:910–922. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caroni P, Savio T, Schwab ME. Central nervous system regeneration: oligodendrocytes and myelin as non-permissive substrates for neurite growth. Progress in Brain Research. 1988;78:363–370. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)60305-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen P, Goldberg DE, Kolb B, Lanser M, Benowitz LI. Inosine induces axonal rewiring and improves behavioral outcome after stroke. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9031–9036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132076299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng L, Sapieha P, Kittlerova P, Hauswirth WW, Di Polo A. TrkB gene transfer protects retinal ganglion cells from axotomy-induced death in vivo. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3977–3986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-10-03977.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho EY, So KF. Characterization of the sprouting response of axon-like processes from retinal ganglion cells after axotomy in adult hamsters: a model using intravitreal implantation of a peripheral nerve. Journal of Neurocytology. 1992;21:589–603. doi: 10.1007/BF01187119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costigan M, Befort K, Karchewski L, Griffin RS, D'Urso D, Allchorne A, Sitarski J, Mannion JW, Pratt RE, Woolf CJ. Replicate high-density rat genome oligonucleotide microarrays reveal hundreds of regulated genes in the dorsal root ganglion after peripheral nerve injury. BMC Neurosci. 2002;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui Q, Cho KS, So KF, Yip HK. Synergistic effect of Nogo-neutralizing antibody IN-1 and ciliary neurotrophic factor on axonal regeneration in adult rodent visual systems. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:617–625. doi: 10.1089/089771504774129946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui Q, Yip HK, Zhao RC, So KF, Harvey AR. Intraocular elevation of cyclic AMP potentiates ciliary neurotrophic factor-induced regeneration of adult rat retinal ganglion cell axons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;22:49–61. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(02)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dancause N, Barbay S, Frost SB, Plautz EJ, Chen D, Zoubina EV, Stowe AM, Nudo RJ. Extensive cortical rewiring after brain injury. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10167–10179. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3256-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.David S, Aguayo AJ. Axonal elongation into peripheral nervous system “bridges” after central nervous system injury in adult rats. Science. 1981;214:931–933. doi: 10.1126/science.6171034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies SJ, Fitch MT, Memberg SP, Hall AK, Raisman G, Silver J. Regeneration of adult axons in white matter tracts of the central nervous system. Nature. 1997;390:680–683. doi: 10.1038/37776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Doster SK, Lozano AM, Aguayo AJ, Willard MB. Expression of the growth-associated protein GAP-43 in adult rat retinal ganglion cells following axon injury. Neuron. 1991;6:635–647. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellezam B, Selles-Navarro I, Manitt C, Kennedy TE, McKerracher L. Expression of netrin-1 and its receptors DCC and UNC-5H2 after axotomy and during regeneration of adult rat retinal ganglion cells. Exp Neurol. 2001;168:105–115. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischer D, He Z, Benowitz LI. Counteracting the Nogo receptor enhances optic nerve regeneration if retinal ganglion cells are in an active growth state. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1646–1651. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5119-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer D, Heiduschka P, Thanos S. Lens-injury-stimulated axonal regeneration throughout the optic pathway of adult rats. Exp Neurol. 2001;172:257–272. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fischer D, Pavlidis M, Thanos S. Cataractogenic lens injury prevents traumatic ganglion cell death and promotes axonal regeneration both in vivo and in culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3943–3954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer D, Petkova V, Thanos S, Benowitz LI. Switching mature retinal ganglion cells to a robust growth state in vivo: gene expression and synergy with RhoA inactivation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8726–8740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2774-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallo G, Letourneau PC. Regulation of growth cone actin filaments by guidance cues. J Neurobiol. 2004;58:92–102. doi: 10.1002/neu.10282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberg JL, Vargas ME, Wang JT, Mandemakers W, Oster SF, Sretavan DW, Barres BA. An oligodendrocyte lineage-specific semaphorin, Sema5A, inhibits axon growth by retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4989–4999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4390-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greene LA, Volonte C, Chalazonitis A. Purine analogs inhibit nerve growth factor-promoted neurite outgrowth by sympathetic and sensory neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:1479–1485. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-05-01479.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hagino S, Iseki K, Mori T, Zhang Y, Hikake T, Yokoya S, Takeuchi M, Hasimoto H, Kikuchi S, Wanaka A. Slit and glypican-1 mRNAs are coexpressed in the reactive astrocytes of the injured adult brain. Glia. 2003;42:130–138. doi: 10.1002/glia.10207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanz S, Perlson E, Willis D, Zheng JQ, Massarwa R, Huerta JJ, Koltzenburg M, Kohler M, van-Minnen J, Twiss JL, Fainzilber M. Axoplasmic importins enable retrograde injury signaling in lesioned nerve. Neuron. 2003;40:1095–1104. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00770-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He Q, Dent EW, Meiri KF. Modulation of actin filament behavior by GAP-43 (neuromodulin) is dependent on the phosphorylation status of serine 41, the protein kinase C site. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3515–3524. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03515.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herdegen T, Skene P, Bahr M. The c-Jun transcription factor--bipotential mediator of neuronal death, survival and regeneration. Trends in Neurosciences. 1997;20:227–231. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)01000-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu Y, Cui Q, Harvey AR. Interactive effects of C3, cyclic AMP and ciliary neurotrophic factor on adult retinal ganglion cell survival and axonal regeneration. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;34:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irwin N, Li YM, O'Toole JE, Benowitz LI. Mst3b, a purine-sensitive Ste20-like protein kinase, regulates axon outgrowth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18320–18325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605135103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jo S, Wang E, Benowitz LI. CNTF is an endogenous axon regeneration factor for mammalian retinal ganglion cells. Neuroscience. 1999;89:579–591. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00546-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones TA, Kleim JA, Greenough WT. Synaptogenesis and dendritic growth in the cortex opposite unilateral sensorimotor cortex damage in adult rats: a quantitative electron microscopic examination. Brain Res. 1996;733:142–148. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00792-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaneko S, Iwanami A, Nakamura M, Kishino A, Kikuchi K, Shibata S, Okano HJ, Ikegami T, Moriya A, Konishi O, Nakayama C, Kumagai K, Kimura T, Sato Y, Goshima Y, Taniguchi M, Ito M, He Z, Toyama Y, Okano H. A selective Sema3A inhibitor enhances regenerative responses and functional recovery of the injured spinal cord. Nat Med. 2006;12:1380–1389. doi: 10.1038/nm1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kawamata T, Dietrich WD, Schallert T, Gotts JE, Cocke RR, Benowitz LI, Finklestein SP. Intracisternal basic fibroblast growth factor enhances functional recovery and up-regulates the expression of a molecular marker of neuronal sprouting following focal cerebral infarction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:8179–8184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawamata T, Ren J, Chan TC, Charette M, Finklestein SP. Intracisternal osteogenic protein-1 enhances functional recovery following focal stroke. Neuroreport. 1998;9:1441–1445. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199805110-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolb B, Morshead C, Gonzalez C, Kim M, Gregg C, Shingo T, Weiss S. Growth factor-stimulated generation of new cortical tissue and functional recovery after stroke damage to the motor cortex of rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lau KC, So KF, Tay D. Intravitreal transplantation of a segment of peripheral nerve enhances axonal regeneration of retinal ganglion cells following distal axotomy. Experimental Neurology. 1994;128:211–215. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laux T, Fukami K, Thelen M, Golub T, Frey D, Caroni P. GAP43, MARCKS, and CAP23 modulate PI(4,5)P(2) at plasmalemmal rafts, and regulate cell cortex actin dynamics through a common mechanism. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1455–1472. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lazarov-Spiegler O, Solomon AS, Schwartz M. Peripheral nerve-stimulated macrophages simulate a peripheral nerve-like regenerative response in rat transected optic nerve. Glia. 1998;24:329–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leaver SG, Cui Q, Plant GW, Arulpragasam A, Hisheh S, Verhaagen J, Harvey AR. AAV-mediated expression of CNTF promotes long-term survival and regeneration of adult rat retinal ganglion cells. Gene Ther. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee JK, Kim JE, Sivula M, Strittmatter SM. Nogo receptor antagonism promotes stroke recovery by enhancing axonal plasticity. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6209–6217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1643-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lehmann M, Fournier A, Selles-Navarro I, Dergham P, Sebok A, Leclerc N, Tigyi G, McKerracher L. Inactivation of Rho signaling pathway promotes CNS axon regeneration. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7537–7547. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07537.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leon S, Yin Y, Nguyen J, Irwin N, Benowitz LI. Lens injury stimulates axon regeneration in the mature rat optic nerve. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4615–4626. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04615.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li Y, Irwin N, Yin Y, Lanser M, Benowitz LI. Axon regeneration in goldfish and rat retinal ganglion cells: differential responsiveness to carbohydrates and cAMP. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7830–7838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07830.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lindvall O, Kokaia Z. Stem cells for the treatment of neurological disorders. Nature. 2006;441:1094–1096. doi: 10.1038/nature04960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Logan A, Ahmed Z, Baird A, Gonzalez AM, Berry M. Neurotrophic factor synergy is required for neuronal survival and disinhibited axon regeneration after CNS injury. Brain. 2006;129:490–502. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lorber B, Berry M, Logan A. Lens injury stimulates adult mouse retinal ganglion cell axon regeneration via both macrophage- and lens-derived factors. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2029–2034. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lorber B, Berry M, Logan A, Tonge D. Effect of lens lesion on neurite outgrowth of retinal ganglion cells in vitro. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;21:301–311. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lu X, Richardson PM. Inflammation near the nerve cell body enhances axonal regeneration. J Neurosci. 1991;11:972–978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-04-00972.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Manitt C, Colicos MA, Thompson KM, Rousselle E, Peterson AC, Kennedy TE. Widespread expression of netrin-1 by neurons and oligodendrocytes in the adult mammalian spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3911–3922. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-03911.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mansour-Robaey S, Clarke DB, Wang YC, Bray GM, Aguayo AJ. Effects of ocular injury and administration of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on survival and regrowth of axotomized retinal ganglion cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91:1632–1636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martin KR, Klein RL, Quigley HA. Gene delivery to the eye using adeno-associated viral vectors. Methods. 2002;28:267–275. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(02)00232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McKeon RJ, Schreiber RC, Rudge JS, Silver J. Reduction of neurite outgrowth in a model of glial scarring following CNS injury is correlated with the expression of inhibitory molecules on reactive astrocytes. Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11:3398–3411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-11-03398.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McKerracher L, David S, Jackson DL, Kottis V, Dunn RJ, Braun PE. Identification of myelin-associated glycoprotein as a major myelin- derived inhibitor of neurite growth. Neuron. 1994;13:805–811. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90247-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Meyer RL, Miotke JA, Benowitz LI. Injury induced expression of growth-associated protein-43 in adult mouse retinal ganglion cells in vitro. Neuroscience. 1994;63:591–602. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90552-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mi S, Lee X, Shao Z, Thill G, Ji B, Relton J, Levesque M, Allaire N, Perrin S, Sands B, Crowell T, Cate RL, McCoy JM, Pepinsky RB. LINGO-1 is a component of the Nogo-66 receptor/p75 signaling complex. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:221–228. doi: 10.1038/nn1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Monsul NT, Geisendorfer AR, Han PJ, Banik R, Pease ME, Skolasky RL, Jr, Hoffman PN. Intraocular injection of dibutyryl cyclic AMP promotes axon regeneration in rat optic nerve. Exp Neurol. 2004;186:124–133. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00311-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moreau-Fauvarque C, Kumanogoh A, Camand E, Jaillard C, Barbin G, Boquet I, Love C, Jones EY, Kikutani H, Lubetzki C, Dusart I, Chedotal A. The transmembrane semaphorin Sema4D/CD100, an inhibitor of axonal growth, is expressed on oligodendrocytes and upregulated after CNS lesion. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9229–9239. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-27-09229.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mukhopadhyay G, Doherty P, Walsh FS, Crocker PR, Filbin MT. A novel role for myelin-associated glycoprotein as an inhibitor of axonal regeneration. Neuron. 1994;13:757–767. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ng TF, So KF, Chung SK. Influence of peripheral nerve grafts on the expression of GAP-43 in regenerating retinal ganglion cells in adult hamsters. Journal of Neurocytology. 1995;24:487–496. doi: 10.1007/BF01179974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Niederost B, Oertle T, Fritsche J, McKinney RA, Bandtlow CE. Nogo-A and myelin-associated glycoprotein mediate neurite growth inhibition by antagonistic regulation of RhoA and Rac1. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10368–10376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10368.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nikolic M. The role of Rho GTPases and associated kinases in regulating neurite outgrowth. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34:731–745. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oertle T, van der Haar ME, Bandtlow CE, Robeva A, Burfeind P, Buss A, Huber AB, Simonen M, Schnell L, Brosamle C, Kaupmann K, Vallon R, Schwab ME. Nogo-A inhibits neurite outgrowth and cell spreading with three discrete regions. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5393–5406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05393.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ohab JJ, Fleming S, Blesch A, Carmichael ST. A neurovascular niche for neurogenesis after stroke. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13007–13016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4323-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Okada T, Ichikawa M, Tokita Y, Horie H, Saito K, Yoshida J, Watanabe M. Intravitreal macrophage activation enables cat retinal ganglion cells to regenerate injured axons into the mature optic nerve. Exp Neurol. 2005;196:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ono K, Yasui Y, Rutishauser U, Miller RH. Focal ventricular origin and migration of oligodendrocyte precursors into the chick optic nerve. Neuron. 1997;19:283–292. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Papadopoulos CM, Tsai SY, Alsbiei T, O'Brien TE, Schwab ME, Kartje GL. Functional recovery and neuroanatomical plasticity following middle cerebral artery occlusion and IN-1 antibody treatment in the adult rat. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:433–441. doi: 10.1002/ana.10144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Park JB, Yiu G, Kaneko S, Wang J, Chang J, He XL, Garcia KC, He Z. A TNF receptor family member, TROY, is a coreceptor with Nogo receptor in mediating the inhibitory activity of myelin inhibitors. Neuron. 2005;45:345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Park K, Luo JM, Hisheh S, Harvey AR, Cui Q. Cellular mechanisms associated with spontaneous and ciliary neurotrophic factor-cAMP-induced survival and axonal regeneration of adult retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10806–10815. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3532-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Perlson E, Hanz S, Ben-Yaakov K, Segal-Ruder Y, Seger R, Fainzilber M. Vimentin-dependent spatial translocation of an activated MAP kinase in injured nerve. Neuron. 2005;45:715–726. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pernet V, Di Polo A. Synergistic action of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and lens injury promotes retinal ganglion cell survival, but leads to optic nerve dystrophy in vivo. Brain. 2006 doi: 10.1093/brain/awl015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pizzorusso T, Medini P, Berardi N, Chierzi S, Fawcett JW, Maffei L. Reactivation of ocular dominance plasticity in the adult visual cortex. Science. 2002;298:1248–1251. doi: 10.1126/science.1072699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Raivich G, Bohatschek M, Da Costa C, Iwata O, Galiano M, Hristova M, Nateri AS, Makwana M, Riera-Sans L, Wolfer DP, Lipp HP, Aguzzi A, Wagner EF, Behrens A. The AP-1 transcription factor c-Jun is required for efficient axonal regeneration. Neuron. 2004;43:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ramon y Cajal S. Degeneration and Regeneration of the Nervous System. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Richardson PM, McGuinness UM, Aguayo AJ. Axons from CNS neurons regenerate into PNS grafts. Nature. 1980;284:264–265. doi: 10.1038/284264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rudge JS, Silver J. Inhibition of neurite outgrowth on astroglial scars in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience. 1990;10:3594–3603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03594.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schaden H, Stuermer CA, Bahr M. GAP-43 immunoreactivity and axon regeneration in retinal ganglion cells of the rat. Journal of Neurobiology. 1994;25:1570–1578. doi: 10.1002/neu.480251209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schnell L, Schneider R, Kolbeck R, Barde YA, Schwab ME. Neurotrophin-3 enhances sprouting of corticospinal tract during development and after adult spinal cord lesion. Nature. 1994;367:170–173. doi: 10.1038/367170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schwab ME. Repairing the injured spinal cord. Science. 2002;295:1029–1031. doi: 10.1126/science.1067840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schwab ME, Caroni P. Oligodendrocytes and CNS myelin are nonpermissive substrates for neurite growth and fibroblast spreading in vitro. Journal of Neuroscience. 1988;8:2381–2393. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-07-02381.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schwab ME, Thoenen H. Dissociated neurons regenerate into sciatic but not optic nerve explants in culture irrespective of neurotrophic factors. J Neurosci. 1985;5:2415–2423. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-09-02415.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schwalb JM, Boulis NM, Gu MF, Winickoff J, Jackson PS, Irwin N, Benowitz LI. Two factors secreted by the goldfish optic nerve induce retinal ganglion cells to regenerate axons in culture. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15:5514–5525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-08-05514.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schwalb JM, Gu MF, Stuermer C, Bastmeyer M, Hu GF, Boulis N, Irwin N, Benowitz LI. Optic nerve glia secrete a low-molecular-weight factor that stimulates retinal ganglion cells to regenerate axons in goldfish. Neuroscience. 1996;72:901–910. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00605-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schweigreiter R, Walmsley AR, Niederost B, Zimmermann DR, Oertle T, Casademunt E, Frentzel S, Dechant G, Mir A, Bandtlow CE. Versican V2 and the central inhibitory domain of Nogo-A inhibit neurite growth via p75NTR/NgR-independent pathways that converge at RhoA. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:163–174. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Seijffers R, Allchorne AJ, Woolf CJ. The transcription factor ATF-3 promotes neurite outgrowth. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;32:143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Silver J, Miller JH. Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:146–156. doi: 10.1038/nrn1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Skene JH, Willard M. Changes in axonally transported proteins during axon regeneration in toad retinal ganglion cells. Journal of Cell Biology. 1981b;89:86–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.89.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.So KF, Aguayo AJ. Lengthy regrowth of cut axons from ganglion cells after peripheral nerve transplantation into the retina of adult rats. Brain Research. 1985;328:349–354. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Song H, Ming G, He Z, Lehmann M, McKerracher L, Tessier-Lavigne M, Poo M. Conversion of neuronal growth cone responses from repulsion to attraction by cyclic nucleotides. Science. 1998;281:1515–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Steinmetz MP, Horn KP, Tom VJ, Miller JH, Busch SA, Nair D, Silver DJ, Silver J. Chronic enhancement of the intrinsic growth capacity of sensory neurons combined with the degradation of inhibitory proteoglycans allows functional regeneration of sensory axons through the dorsal root entry zone in the mammalian spinal cord. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8066–8076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2111-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Stroemer RP, Kent TA, Hulsebosch CE. Neocortical neural sprouting, synaptogenesis, and behavioral recovery after neocortical infarction in rats. Stroke. 1995;26:2135–2144. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.11.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.van Adel BA, Kostic C, Deglon N, Ball AK, Arsenijevic Y. Delivery of ciliary neurotrophic factor via lentiviral-mediated transfer protects axotomized retinal ganglion cells for an extended period of time. Hum Gene Ther. 2003;14:103–115. doi: 10.1089/104303403321070801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Venkatesh K, Chivatakarn O, Lee H, Joshi PS, Kantor DB, Newman BA, Mage R, Rader C, Giger RJ. The Nogo-66 receptor homolog NgR2 is a sialic aciddependent receptor selective for myelin-associated glycoprotein. J Neurosci. 2005;25:808–822. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4464-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vidal-Sanz M, Bray GM, Villegas-Perez MP, Thanos S, Aguayo AJ. Axonal regeneration and synapse formation in the superior colliculus by retinal ganglion cells in the adult rat. Journal of Neuroscience. 1987;7:2894–2909. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-09-02894.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Volonte C, Greene LA. Nerve growth factor-activated protein kinase N. Characterization and rapid near homogeneity purification by nucleotide affinity-exchange chromatography. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267:21663–21670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Volonte C, Rukenstein A, Loeb DM, Greene LA. Differential inhibition of nerve growth factor responses by purine analogues: correlation with inhibition of a nerve growth factor-activated protein kinase. Journal of Cell Biology. 1989;109:2395–2403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.5.2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang KC, Kim JA, Sivasankaran R, Segal R, He Z. p75 interacts with the Nogo receptor as a co-receptor for Nogo, MAG and OMgp. Nature. 2002;420:74–78. doi: 10.1038/nature01176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang KC, Koprivica V, Kim JA, Sivasankaran R, Guo Y, Neve RL, He Z. Oligodendrocyte-myelin glycoprotein is a Nogo receptor ligand that inhibits neurite outgrowth. Nature. 2002;417:941–944. doi: 10.1038/nature00867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Weibel D, Cadelli D, Schwab ME. Regeneration of lesioned rat optic nerve fibers is improved after neutralization of myelin-associated neurite growth inhibitors. Brain Research. 1994;642:259–266. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90930-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Weidner N, Ner A, Salimi N, Tuszynski MH. Spontaneous corticospinal axonal plasticity and functional recovery after adult central nervous system injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3513–3518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051626798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yin Y, Cui Q, Li Y, Irwin N, Fischer D, Harvey AR, Benowitz LI. Macrophage-derived factors stimulate optic nerve regeneration. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:2284–2293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02284.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yin Y, Henzl MT, Lorber B, Nakazawa T, Thomas TT, Jiang F, Langer R, Benowitz LI. Oncomodulin is a macrophage-derived signal for axon regeneration in retinal ganglion cells. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:843–852. doi: 10.1038/nn1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zheng B, Atwal J, Ho C, Case L, He XL, Garcia KC, Steward O, Tessier-Lavigne M. Genetic deletion of the Nogo receptor does not reduce neurite inhibition in vitro or promote corticospinal tract regeneration in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1205–1210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409026102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zheng B, Ho C, Li S, Keirstead H, Steward O, Tessier-Lavigne M. Lack of enhanced spinal regeneration in nogo-deficient mice. Neuron. 2003;38:213–224. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zurn A, Do K. Purine metabolite inosine is an adrenergic neurotrophic substance for cultured chicken sympathetic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:8301–8305. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.8301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]