Summary

Setting

Although patients should know the level of training of the physician providing their care in teaching hospitals, many do not.

Objective

The objective of this study is to determine whether the manner by which physicians introduce themselves to patients is associated with patients’ misperception of the level of training of their physician.

Patients/Participants

This was an observational study of 100 patient–physician interactions in a teaching emergency department.

Measurements and Main Results

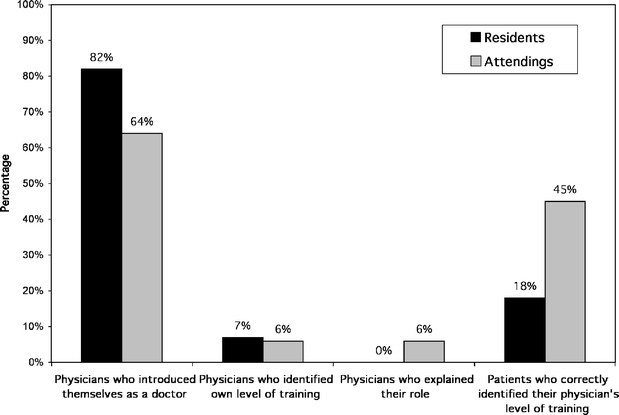

Residents introduced themselves as a doctor 82% of the time but identified themselves as a resident only 7% of the time. While attending physicians introduced themselves as a “doctor” 64% of the time, only 6% identified themselves as the supervising physician. Patients felt it was very important to know their physicians’ level of training, but most did not.

Conclusions

Physicians in our sample were rarely specific about their level of training and role in patient care when introducing themselves to patients. This lack of communication may contribute to patients’ lack of knowledge regarding who is caring for them in a teaching hospital.

KEY WORDS: physician–patient relations, graduate medical education, teaching hospitals

While the process of medical training is well understood by those who undertake this path, the roles and responsibilities may not be as clear to patients. The American Medical Association and the American College of Physicians Ethics Manual have stated that all trainees should inform patients of their training status and role in the medical team.1,2 However, studies have shown the majority of patients do not understand the different levels of physician training.3,4 If residents routinely explained their level of training and inherent responsibilities, it might be reasonable to expect that patients should have some understanding of the training status of their doctors.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether physicians’ failure to communicate their level of training and their role in providing care contributes to patients’ inability to identify the training status of their physician.

METHODS

This study was conducted with a convenience sample 100 physician–patient interactions at a teaching hospital emergency department. Exclusion criteria included refusal to participate, critical illness, altered mental status, or inability to speak English. This study was Institutional Review Board approved. Patients verbally consented. Physicians were not aware of the purpose of the study and were told the researcher was observing medical care and were entitled to refuse to participate (none refused).

This was a two-part study; first was an observation of 100 patient–physician interactions during the initial patient encounter. The investigator (TSR) documented the following information: did the physicians introduce themselves as a doctor, state their level of training (resident, or attending), and explain their role in the patients’ care?

After the initial patient encounter, patients completed a survey to determine whether they could identify their physicians’ level of training and understood resident training and assessed their attitudes towards treatment in a teaching hospital. The survey collected demographic information. The survey was similar to that used in other studies,3,4 and the patient knowledge section had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76.

Descriptive summary statistics were generated using SPSS Mac 10. The responses to the opinion-based questions are collapsed into agree/disagree/neutral. Odds ratios were calculated, and multivariate analysis was performed with binary logistic regression.

RESULTS

A total of 100 patient interactions were observed: 33 attending–patient and 67 resident–patient. There were 7 attendings and 25 residents observed. Five of the physicians were women. Thirteen patients were excluded, and no patient refused to participate. The demographic characteristics of the patient participants were: mean age 44 years, 63% women, 63% White, and 46% had more than a high-school diploma.

While some physicians identified themselves as doctors, few noted their level of training or role in patient care (Fig. 1). Both residents and attendings explained their role and level of training less than 10% of the time. Physicians were more likely to introduce themselves as a physician with White as compared to African-American patients (83 vs 65%, p < 0.05). However, there was no difference in explanation of their level of training based on race of the patient. When asked to identify their physician, patients had difficulty identifying the resident (18%, 12 of 67) and attending (45%, 15 of 33). Patients were able to correctly identify the level of their physician in 71% (5 of 7) of the interactions in which the physician identified his/her level of training but only in 24% (22 of 93) of the interactions where the level was not identified (p < 0.005). Most patients (60%, 40 of 67) believed that the resident was an attending and 27% (9 of 33) believed the attending was a resident. The gender of the physician did not affect whether the patient correctly identified the training. Only 11% of African Americans (4 of 37) were able to identify the training of the physician compared to 37% (23 of 63) of Whites. In multivariate analysis, physician explanation of role [odds ratio (OR) 8.9, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.7–45.5] and the race of the patient (African American, OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.04–0.59), were associated with whether the patient was able to determine the training of the physician. Education level, gender, and the number of emergency department (ED) visits in the past 5 years had no association.

Figure 1.

Results of Observed Encounters of Physician–Patient Communication

Patients showed a lack of understanding of resident training (Table 1). Although most patients (74%) felt that it was very important to know the level of training of their physician and felt that they usually knew the level of their doctor’s training, only 27% actually could recall this accurately.

Table 1.

Patients’ Knowledge of Physicians’ Level of Training and Attitudes about Medical Care in a Teaching Hospital

| Agree* (%) | Disagree (%) | Do not Know or Neutral (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| An attending doctor requires supervision by a resident | 27 | 54 | 19 |

| A resident has completed medical school | 58 | 36 | 6 |

| A resident is the most highly trained doctor in the ED | 17 | 73 | 10 |

| An attending doctor gives orders to the resident | 73 | 14 | 13 |

| A resident requires no supervision when caring for patients | 32 | 58 | 10 |

| Medical students, interns, and residents are at different levels of training | 96 | 1 | 3 |

| A resident has not yet completed medical school | 33 | 56 | 11 |

| A resident is the boss in the emergency department | 12 | 70 | 18 |

| An attending doctor has completed all medical training and requires no supervision when caring for patients | 56 | 28 | 16 |

| A resident requires several years of training to become an attending doctor | 75 | 16 | 9 |

| It is very important to know the level of training of my doctor when I am being treated in the ED | 74 | 14 | 12 |

| I usually know whether the doctor that cares for me is a medical student, resident, or attending doctor when I am treated in the ED | 73 | 9 | 18 |

| I prefer to be treated in a hospital that has doctors in training | 47 | 41 | 12 |

| Because doctors need training, it is okay for them to learn on me as long as they are supervised | 74 | 7 | 19 |

| I feel comfortable that my doctor is a supervised doctor-in-training | 70 | 9 | 21 |

*As there are 100 patients, the percentages equal the number of patients.

DISCUSSION

Although informing patients of the training status of residents is mandated,1,2,5 studies have shown that patients do not know that physicians-in-training are providing their medical care.3,4 By observing the initial physician–patient interaction, we were able to document that physicians rarely divulge these important details, but when they do clearly identify themselves, the majority of patients could correctly identify the level of the physician when later asked. Patients did not understand that, while residents are doctors, they are still in training and must be supervised by an attending. These results imply that even if a patient is told the “title” of their physician, unless additional information is given, there is a reasonable probability that they will not understand the implications.

Research has shown that improving patient–physician relationships leads to increased compliance and fewer malpractice claims.6–8 The discrepancy between the importance patients place on knowing who is treating them and their actual knowledge is a potential source of patient dissatisfaction.9 This is particularly important because some patients may feel uncomfortable with the idea of receiving care from a doctor-in-training. In fact, half of our patients were either unsure or did not prefer to be treated in a hospital that has physician trainees.

The ethical principles of patient autonomy, truth telling, and informed consent as the basis for patient–physician relationship are taught in most formal medical school curricula.10 The “hidden curriculum” is the socialization that occurs outside the formal teaching and undermines both these principles and a physician’s professional development.11 Physicians’ lack of truthfulness regarding their training level may well be a consequence of the “hidden curriculum.” Residents might not be forthcoming regarding their level of training because they fear that a fully informed patient may refuse to allow a trainee to participate in their care.12 There is some evidence to the contrary.13,14 For example, one study found that up to 92% of patients would allow an inexperienced medical student to perform a procedure.13 Other studies have shown that patients are willing to allow residents to perform spinal taps.14,15 Thus, it is likely that skillful honest communication with patients will not interfere significantly with meeting the training needs of residents.

The doctors in this study were more likely to introduce themselves as a physician with White patients than with African-American patients, although they were equally likely to explain their level of training to patients of either racial group. African-American patients were less likely to identify the level of training of their physician accurately even when accounting for patient’s level of education. These results represent racial disparities in physician–patient communication, although the impact on quality of medical care is not known.

While this study was conducted in the ED, most clinical specialties face similar environments in which a variety of providers are involved in an individual patient’s care. Our findings suggest that medical educators need to create curriculum and modeling to encourage physicians to routinely and clearly identify themselves and their role in patient care. This is important because we are ethically bound to ensure that patients understand medical training enough to be truly informed about the abilities and supervision of their physicians.

This study suggests that poor communication leads to limited knowledge on the part of patients. The generalizability of our findings is limited by a small sample size from a single institution. In addition, because we excluded non-English-speaking patients, we do not know what the impact of a language barrier would have been on our findings. In the future, other studies might explore the attitudinal and emotional impact on patients once they discover they were under mistaken assumptions about their physician’s level of training and experience. Also, of interest is whether a physician’s failure to adequately introduce him or herself is a marker for other skill limitations or a set of attitudes which limit the delivery of good medical care.

In conclusion, patients have a right to and think it is important to know the training level of their physician, but the majority did not know. Physicians’ failure to communicate this simple information no doubt contributes to patients’ lack of knowledge which has implications for ethical and quality medical practice.

Acknowledgements

There was no funding of this research. This paper was presented at ACEP Research Forum 2000, and the Southern Medical Association Annual Meeting 2000.

Conflict of Interest None disclosed.

References

- 1.The Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs of the American Medical Association. Medical student’s involvement in patient care. J Clin Ethics. 2001;12:111–5. 11642059

- 2.The American College of Physicians. Ethics manual. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:576–94. [PubMed]

- 3.Santen SA, Hemphill, Prough EE, Perlowski AA. Do patients understand their physicians’ level of training? A survey of emergency department patients. Acad Med. 2004;79:144–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hemphill RR, Santen SA, Rountree CB, Szmit AR. Patients’ understanding of the roles of interns, residents, and attending physicians in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:339–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Joint Commission of Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, Accreditation Manual for Hospitals. [monograph on line]. Oakbrook Terrace: Joint Commission Resource Inc.; 2002 [updated 2002 May 2, cited 2002 May 29]. Sections RI.1.2, MS 2.5 and 6.9.

- 6.Levinson W, Roter DL, Mullooly JP, Dull VT, Frankel RM. Physician–patient communication: the relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277:555–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Smith RC, Lyles JS, Mettler MA, et al.. A strategy for improving patient satisfaction by the intensive training of residents in psychosocial medicine: a controlled, randomized study. Acad Med. 1995;70:729–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR. Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior and medical encounters. Med Care. 1988;26:657–75. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Wendler DS, Shah S. How can medical training and informed consent be reconciled with volume outcome data. J Clin Ethics. 2006;17:149–57. [PubMed]

- 10.Lo B. Resolving Ethical Dilemmas, A Guide for Clinicians. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2000:19–28.

- 11.Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69:861–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Beatty ME, Lewis J. When students introduce themselves as doctors to patients. Acad Med. 1995;70:175–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Santen SA, Hemphill RR, Spanier CM, Fletcher N. “Sorry, it’s my first time!” Will patients consent to medical students learning procedures. Med Educ. 2005;39:365–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Williams CT, Fost N. Ethical considerations surrounding first time procedures: a study and analysis of patient attitudes toward spinal taps by students. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 1992;2:217–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Santen SA, Hemphill RR, McDonald MF, Jo CO. Patient willingness to allow residents to learn to practice medical procedures. Acad Med. 2004;79:139–43. [DOI] [PubMed]