Abstract

We have previously reported the TLR4 expression in human intestinal lymphatic vessels. In the study here, microarray analysis showed the expression of the TLR4, MD-2, CD14, MyD88, TIRAP, TRAM, IRAK1, and TRAF6 genes in cultured human neonatal dermal lymphatic microvascular endothelial cells (LEC). The microarray analysis also showed that LEC expressed genes of IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1, and the real-time quantitative PCR analysis showed that mRNA production was increased by lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 production in LEC was suppressed by the introduction of TLR4-specific small interfering RNA, and also by anti-TLR4, nobiletin, and CAPE pretreatment. These findings suggest that LEC has TLR4-mediated LPS recognition mechanisms that involve at least activation of NF-κB, resulting in increased expression of IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1. Both the LPS effect on the gene expression and also the suppression by nobiletin and CAPE pretreatment on the protein production were larger in IL-6 and in VCAM-1 than in IL-8 and in ICAM-1 in LEC. The signal transduction of NF-κB and AP-1-dependent pathway may be more critical for the expression of IL-6 and VCAM-1 than that of IL-8 and ICAM-1 in LEC. (J Histochem Cytochem 56:97–109, 2008)

Keywords: lymphatic endothelium, lipopolysaccharide, IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, ICAM-1

Lymphatic vessels express not only platelet-endothelial adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1) but also the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in inflamed and uninflamed human small intestine and tongue, and lymphatic endothelium enhances VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 production with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (Sawa et al. 1999,2007; Ebata et al. 2001). It is well established that VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 induction needs a signaling pathway that involves protein kinase C and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs)-mediated activation of transcription factors nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kB) and activator protein 1 (AP-1) (Voraberger et al. 1991; Ahmad et al. 1998; Ishizuka et al. 1998; Oertli et al. 1998; Kobuchi et al. 1999; Lawson et al. 1999; Roebuck 1999). It is thought that lymphatic endothelium has signal transduction pathways to induce leukocyte adhesion molecule expression through receptors for inflammatory cytokines. However, it has not been established whether lymphatic endothelium has the expression mechanisms of immunological functional molecules independent of the inflammatory cytokines.

The toll-like receptor (TLR) initiates a series of innate immune mechanisms against various microorganism infections by sensing the presence of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) like lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is the major component of the outer surface of Gram-negative bacteria. The LPS stimulates leukocyte and blood endothelium through the LPS recognition systems, binding with CD14 and transferring to TLR4 and MD-2 complex, followed by a myleoid differentiation primary response protein (MyD88)-dependent or -independent pathway that culminates in the early- or late-phase activation of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex and MAPKs. The TLR4 ligand engagements finally result in the production of downstream inflammatory cytokines and leukocyte adhesion molecules by the activation of NF-κB- and AP-1-dependent transcriptional pathways (Aderem and Ulevitch 2000; Ozinsky et al. 2000; Kawai et al. 2001; Schnare et al. 2001; Horng et al. 2002; Janssens and Beyaert 2002; Kaisho and Akira 2002; Lien and Ingalls 2002; Martin and Wesche 2002). In the blood endothelium, LPS leads to increases in the expression of interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8, and VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 through TLR4 signal transduction pathways (Faure et al. 2000; Hijiya et al. 2002; Zeuke et al. 2002; Ogawa et al. 2003; Andreakos et al. 2004; Dauphinee and Karsan 2006). We have previously reported immunohistochemical analysis showing that human intestinal lymphatic vessels express TLR4 (Kuroshima et al. 2004). It was hypothesized that lymphatic endothelium recognizes LPS to start effective self-defense systems that result in lymphocyte migration into lymphatic vessels. The study here was designed to investigate the LPS-induced expression dynamics of IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 in cultured human lymphatic endothelium.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Human neonatal dermal lymphatic microvascular endothelial cells (LEC) (HMVEC-dlyNeo; Cambrex Bio Science Walkersville, Inc., Walkersville, MD), and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) (CC-2505; Cambrex) were cultured in endothelial cell basal medium (EGM-2-MV Bulletkit; Cambrex). A permanent cell line of primary human embryonal kidney (HEK) transformed by sheared human adenovirus type 5 DNA (HEK-293; CRL-1573, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), and an isolated clone of HEK-293 cells stably transfected with human TLR4, MD-2, and CD14 genes (tHEK) (293-hTLR4/MD2-CD14; InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco Life Technologies, Inc.; Grand Island, NY).

Immunostaining

The recent discoveries of several lymphatic endothelial markers, including podoplanin and prospero-related homeobox 1 (Prox1), have enabled an analysis of events for the adhesion molecule expression in lymphatic endothelium (Wigle and Oliver 1999; Schacht et al. 2003; Saharinen et al. 2004). This study tested the cultured endothelial phenotype by the expression of podoplanin and Prox1.

A 90% confluent monolayer (5 × 105 cells/well) on poly-l-lysine- (Sigma Diagnostics, Inc.; St. Louis, MO) coated coverslips in a 6-well plate were air dried, fixed in 30% acetone-10 mM PBS (pH 7.2) and treated with 1 μg/ml of rhodamine-conjugated concanavalin A (Con A; Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) diluted in PBS to visualize the cell membrane. The cells were immunostained with 1 μg/ml of rabbit antiserum to human Prox1 (AngioBio Co.; Del Mar, CA) and of monoclonal antibodies to human podoplanin (AngioBio), VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 (R and D Systems, Inc.; Minneapolis, MN), and also immunostained with 5 μg/ml of monoclonal antibodies to TLR4, MD-2, and CD14 (R and D Systems). Cells were further treated with Alexa Fluor (AF) 488 or AF568-conjugated goat anti-mouse or rabbit IgGs (Invitrogen), and examined by laser-scanning confocal microscopy (Axiovert 135M; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with a ×40 oil planapochromatic objective lens (numerical aperture ×1.3).

LPS Treatment of Cultured Cells

A 90% confluent LEC monolayer in a 100-mm culture dish (1 × 107 cells) was cultured in a 10-ml volume of 5% serum medium with 0, 100, and 10,000 ng/ml Escherichia coli 0111:B4-LPS (InvivoGen) for 0.5, 12, and 24 hr, and the gene expression changes were investigated by microarray analysis. The 90% confluent LEC monolayers (5 × 105 cells/well) in 6-well plates were cultured in a 2-ml volume of 5% serum medium with the human recombinant 100 ng/ml LPS (InvivoGen) for 24 hr, tested on the expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 proteins by immunostaining as described above, cultured with 0–10 μg/ml LPS (InvivoGen) for 12 hr, and analyzed on LPS dose-dependent changes of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, IL-6, and IL-8 mRNA expression. The monolayers were also pretreated with goat antiserum to human TLR4 (100 ng/ml) (R and D Systems), with 64 μM nobiletin (Sigma Diagnostics), or with 35 μM caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) (Sigma Diagnostics), followed by treatment with 100 ng/ml LPS (InvivoGen) for 24 hr, and investigated on the suppression against the LPS-induced VCAM-1, ICAM-1, IL-6, and IL-8 expression by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), real-time quantitative PCR, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was prepared using the Qiagen RNeasy protocol and reagents (Qiagen, Inc.; Tokyo, Japan), and submitted to the GeneChip Mapping Array in the Dragon Genomics Center (Takara Bio, Inc.; Yokkaichi, Japan). The image analysis was carried out according to standard Affymetrix protocols (Affymetrix; Santa Clara, CA). The 54,675 probe sets of Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array (Affymetrix) were used for all hybridizations. Data were analyzed with GeneChip Operating Software, version 1.4, including the GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G (Affymetrix; probe pair threshold = 8, control = antisense). Genes with a detection p-value ≤0.04 determined by the statistical program were considered to be present call, those with 0.04<p<0.06 were considered to be marginal call, and those with p≥0.06 were considered to be absent call. The genes were considered to be significant when expression changed at least 2-fold and the changed gene expression included at least one “present absolute call” (Affymetrix algorithm).

Introduction of Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) Against TLR4

Introduction of siRNA into LEC was performed using a cocktail of three predesigned siRNAs for TLR4 and the mock (SHF27A-1376-C to knock down for NM_138554; B-Bridge International, Inc., Moutain View, CA) with the transfection reagent of GenomONE-Neo (HVJ envelope vector kit; Ishihara Sangyo Kaisha, Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Thirty μM siRNA was added to the LEC culture (5 × 105 cells) in 2 ml of medium per well in a 6-well plate. Two days after transfection, LEC was incubated with the medium containing 100 nM/ml LPS, and expression levels of IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 were tested after 12 hr.

RT-PCR and Real-time Quantitative PCR

The total RNA extraction was achieved with a QIAshredder column and RNeasy kit (Qiagen). Contaminating genomic DNA was removed using DNAfree (Ambion; Huntingdon, UK), and the RT was performed on 30 ng of total RNA, followed by 25–30 cycles of PCR for amplification with 50 pM of primer sets using the Ex Taq hot start version (Takara Bio, Inc.; Otsu, Japan). We used primer sets of β-actin (ATGTTTGAGACCTTCAACAC, CACGTCACACTTCATGATGG, 489 bp), Prox1 (TCCGCTCCTCCCAGTTCCTAAGA, CGCTTTGCTCTCAGGTGCTCATC, 589 bp), podoplanin, TLR4 (ACTCCCTCCAGGTTCTTGATTAC, CGGGAATAAAGTCTCT GTAGTGA, 513 bp), MD2 (TTCCACCCTGTTTTCTTCCATA, GGCTCCCAGAAAT AGCTTCAAC, 404 bp), CD14 (CAGTATGCTGACACGGTCAAGG, ATCTCGGAG CGCTAGGGTTTA, 574 bp), VCAM-1 (CGTCTTGGTCAGCCCTTCCT, ACATTCATATACTCCCGCATCCTTC, 460 bp), ICAM-1 (AGGCCACCCCAGAGGACAAC, CCCATTATGACTGCGGCTGCTA, 406 bp), IL-6 (GAACTCCTTCTCCACAAGCGCCTT, CAAAAGACCAGTGATGATTTTCACCAGG, 358 bp), and IL-8 (TCTGCAGCTCTGTGTGAAGG, ACTTCTCCACAACCCTCTGC, 229 bp), where the specificities had been confirmed by the manufacturer (Sigma-Genosys, Ltd.; Cambridge, UK). The PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gel (NuSieve; FMC, Rockland, ME) and visualized by Syber Green (Takara Bio; Otsu, Japan). The correct size of the amplified PCR products was confirmed by gel electrophoresis, and amplification of accurate targets was confirmed by sequence analysis.

One μl of cDNA was amplified in 25 μl of PCR solution (11.5 μl of cDNA solution in water, 1 μl of primer sets, and 12.5 μl of PowerSYBR Green PCR Master Mix) (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA) in a 7500 Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems), and fluorescence was monitored at each cycle. Cycle parameters were 95C for 15 min to activate Taq, followed by 40 cycles of 95C for 15 sec, 58C for 1 min, and 72C for 1 min. For real-time analysis, a standard curve was constructed from amplicons for β-actin in three serial 4-fold dilutions of cDNA stock from LEC untreated with LPS. The β-actin cDNA levels in each sample were quantified against a standard curve by allowing the software to accurately determine the sample β-actin units. The adhesion molecule cDNA levels in each sample were quantified against a standard curve as the sample adhesion molecule units and were normalized to the sample β-actin units. Thus, relative adhesion molecule production units were expressed as arbitrary units, calculated according to the following formula: relative adhesion molecule production units=sample adhesion molecule units/sample β-actin units.

ELISA on the VCAM-1, ICAM-1, IL-6, and IL-8 Protein Production

The IL-6 and IL-8 secretion amounts in the medium of a cell culture as described above were analyzed by an Immunoassay Kit (BioSource International, Inc.; Camarillo, CA). A 0.1-ml volume of the 20-fold dilution of culture medium, or a 0.1-ml volume of recombinant human IL-6 and IL-8 (1.56–12.5 pg/ml) of the kit (BioSource) were incubated in the human anti-IL-6- or anti-IL-8-coated wells in a 96-well microtitration plate for 3 hr at 37C. The wells were treated with 0.1 ml of biotinylated anti-IL-6 or anti-IL-8 for 45 min at 20C, with 0.1 ml of streptavidin-peroxidase solution for 45 min at 20C, and with tetramethylbenzidine for 30 min at 20C. All treatments were performed after washing six times in a washing solution. The absorbance change of the peroxidase-metabolizing substrate of five wells at 450 nm was measured by a microplate reader after incubation for 5 and 15 min at room temperature, and the wells incubated with the unused medium served as blanks. The amounts of IL-6 and IL-8 secreted from cells were expressed as the mean concentration quantified by the binding activity of antibodies for the two to wells incubated with culture medium and standard protein dilution.

The VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 amounts were analyzed on the lysate of whole-cell protein (2 mg/ml) solubilized in 1 ml of cell lysis buffer (pH 7.3; 50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaF, 10 mM Na pyrophosphate, 1% Triton X, and 5% glycerol). The lysate was centrifuged at 12,500 × g for 20 min at 4C, and the supernatant was diluted 1:5 in a 0.1 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6). A 0.2-ml volume of the 6-fold dilution was placed in a 96-well microtitration plate for 4 hr at 37C, incubated with 0.2 ml of 0.1% goat serum, and treated with 0.18 ml of 100 ng/ml mouse monoclonal antibodies for human VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 (R and D Systems) diluted in a 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TTBS) for 1 hr at 37C, and with 0.18 ml of 10 ng/ml peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Amersham Biosciences; Buckinghamshire, UK) diluted in TTBS for 30 min at 37C. All treatments were performed after washing six times in TTBS. A 0.18-ml volume of the substrate (ABTS microwell peroxidase substrate system; KPL, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) was placed in each well in the microtitration plate and the absorbance change of peroxidase-metabolizing substrate of five wells at 405 nm was measured by a microplate reader after incubation for 5 and 15 min at 37C. The wells treated only with a second antibody served as blanks. The amounts of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 produced in cells were estimated by the binding activity of antibodies for the two to the wells, expressed as the mean absorbance change.

Statistics

All experiments were carried out five times, repeatedly, and data are expressed as mean ± SEM. The statistical significance of differences (p<0.01) was determined by the paired two-tailed Student's t-test with STATVIEW 4.51 software (Abacus Concepts; Calabasas, CA).

Results

Expression of Prox1 and Podoplanin

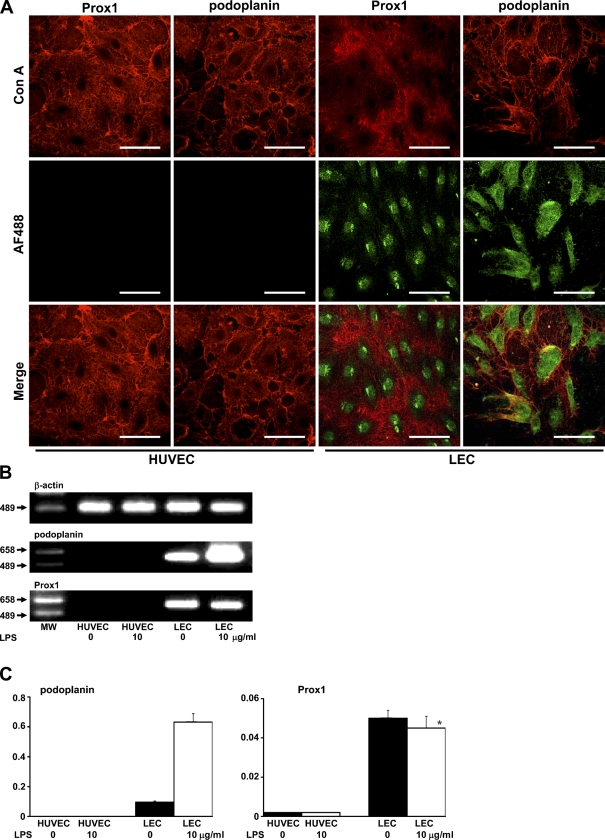

The expression of Prox1 and podoplanin was immunohistochemically observed in the nuclei and in the cytoplasm and cell membrane in LEC, whereas neither Prox1 nor podoplanin was detected in HUVEC (Figure 1A). In the RT-PCR analysis, podoplanin mRNA was detected in LEC and increased with 10 μg/ml LPS, and Prox1 mRNA was detected in LEC but not increased with 10 μg/ml LPS. The podoplanin and Prox1 mRNAs were not detected in HUVEC (Figure 1B). In the real-time quantitative PCR analysis, podoplanin mRNA in LEC with 10 μg/ml LPS showed a 6.58-fold increase compared with LEC without LPS, but was not detected in HUVEC. The Prox1 mRNA did not increase in LEC with LPS and was rarely detected in HUVEC (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Expression of lymphatic endothelial markers. (A) Immunohistochemical analysis. Cells were visualized with rhodamine-conjugated Con A (Con A, in red), and lymphatic endothelial markers were visualized with an AF488-conjugated second antibody (AF488, in green). Merged images indicate that Prox1 and podoplanin are present in nuclei of human neonatal dermal lymphatic microvascular endothelial cells (LEC) and in the cytoplasm and cell membrane, but not in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC). Bar = 100 μm. (B) RT-PCR analysis. The RT-PCR products of podoplanin mRNA were detected in LEC and increased with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The RT-PCR products of Prox1 mRNA were detected in LEC but were not increased with LPS. The podoplanin and Prox1 mRNAs were not detected in HUVEC. MW, molecular weight marker. (C) Real-time quantitative PCR analysis. Podoplanin mRNA in LEC with 10 μg/ml LPS showed a 6.58-fold increase compared with LEC without LPS but was not detected in HUVEC. Prox1 mRNA did not increase in LEC with LPS and was rarely detected in HUVEC. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. *Not significantly different from the untreated cells.

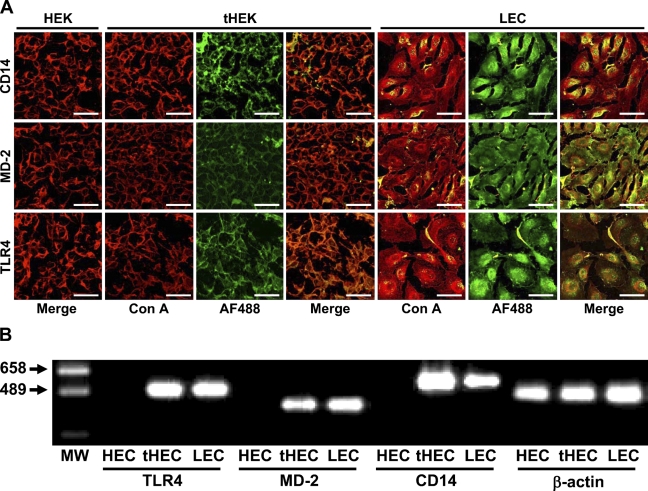

Expression of TLR4, MD-2, and CD14

The expression of TLR4, MD-2, and CD14 was not observed immunohistochemically in HEK-293 used as a negative control but was observed on the membrane of HEK-293 cells stably transfected with human TLR4, MD-2, and CD14 genes (tHEK). The three proteins were detected on the membrane and in the cytoplasm of LEC (Figure 2A). The RT-PCR products for TLR4, MD-2, and CD14 mRNAs were not detected in HEK-293 but were detected in LEC and in tHEK (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Expression of toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), MD-2, and CD14. (A) Immunohistochemical analysis. The cell membrane was visualized with rhodamine-conjugated Con A (Con A, in red), and the reaction products to antibodies for TLR4, MD-2, and CD14 were visualized with an AF488-conjugated second antibody (AF488, in green). Merged images indicate that the expression of TLR4, MD-2, and CD14 was immunohistochemically observed in the cytoplasm and on the cell membrane of LEC, and that the three were detected on the membrane of HEK-293 cells stably transfected with the human TLR4, MD-2, and CD14 genes (tHEK), and not in the negative control HEK-293 cells (HEK). Bar = 100 μm. (B) RT-PCR analysis. RT-PCR products for TLR4, MD-2, and CD14 mRNAs were not detected in HEK-293 but were detected in LEC and in tHEK. MW, molecular weight marker.

Microarray Analysis of LEC Treated With LPS

The strong expression of podoplanin and Prox1 genes was confirmed in LEC (Table 1). The podoplanin gene expression did not increase in LEC with 100 ng/ml LPS but increased 2.83-fold with 10 μg/ml LPS when compared with untreated cells. The Prox1 gene expression in LEC with 100 ng/ml LPS showed a 2-fold increase compared with untreated cells at 30 min but did not show significant differences from the expression of untreated cells at 12 and 24 hr.

Table 1.

Expression of genes for lymphatic endothelial markers, and TLR-associated and leukocyte adhesion molecules in human neonatal dermal lymphatic microvascular endothelial cells with LPS treatments

| Gene names and number of probes (n) | Absolute call for control and detection p-value | Mean 100 ng/ml LPS vs control at 0.5 hr | Mean 100 ng/ml LPS vs control at 12 hr | Mean 100 ng/ml LPS vs control at 24 hr | Mean 10,000 ng/ml LPS vs control at 24 hr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphatic endothelial marker | |||||

| Prox1 (1) | P (0.0002) | 2.00 | NS | NS | NS |

| Podoplanin (3) | P (0.0002) | NS | NS | NS | 2.83 |

| TLR and essential intracellular signal transducer in TLR-mediated cell activation | |||||

| TLR4 (3) | P (0.0002) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| MD2 (1) | P (0.0002) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| CD14 (1) | A (0.69) | A | A | A | P (0.00293) |

| MYD88 (1) | P (0.0002) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| TIRAP (2) | P (0.002) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| TRAM (2) | P (0.0002) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| TRAF6 (1) | P (0.03) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| IRAK1 (1) | P (0.0002) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| TAK1 (1) | P (0.002) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Interleukin and adhesion molecules | |||||

| IL-6 (1) | P (0.01) | NS | NS | NS | 147.03 |

| IL-8 (2) | P (0.0002) | 0.44 | 6.96 | 6.50 | 17.15 |

| VCAM-1 (1) | P (0.0007) | NS | 3.03 | 2.64 | 18.38 |

| ICAM-1 (3) | P (0.0007) | NS | 2.83 | 2.64 | 11.31 |

Genes with a detection p≤0.04 were considered to be present (P), and those with p≥0.06 were considered to be absent (A) when compared with eight antisense control probe pairs. The genes were considered to be significantly increased when expression changed at least 2-fold and the changed gene expression included at least one “present absolute call,” expressed as the relative (-fold) change (mean of eight probe pairs). IL, interleukin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NS, not significant; TLR, toll-like receptor.

The strong expression of TLR4 and MD-2 genes was confirmed in LEC, and the expression did not increase with LPS. The CD14 gene expression was statistically absent in LEC but present in the cells with 10 μg/ml LPS. The gene expression of signal transducer in TLR4-mediated cell activation; MyD88, toll-IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain-containing adaptor protein (TIRAP) mRNA transcript variant 1, translocating chain-associating membrane protein (TRAM), IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1), TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), and transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase (TAK1) were all present in LEC but not altered by LPS.

The IL-6 gene expression was present in LEC but did not increase with 100 ng/ml LPS, and increased to 147.03-fold with 10 μg/ml LPS. The IL-8 gene expression was detected strongly in LEC and increased to 17.15-fold with 10 μg/ml LPS. The LEC expressed VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 genes. The VCAM-1 gene expression was 6.1-fold higher in cells with 10 μg/ml LPS than in cells with 100 ng/ml LPS. The ICAM-1 gene expression was 4-fold higher in cells with 10 μg/ml LPS than in cells with 100 ng/ml LPS.

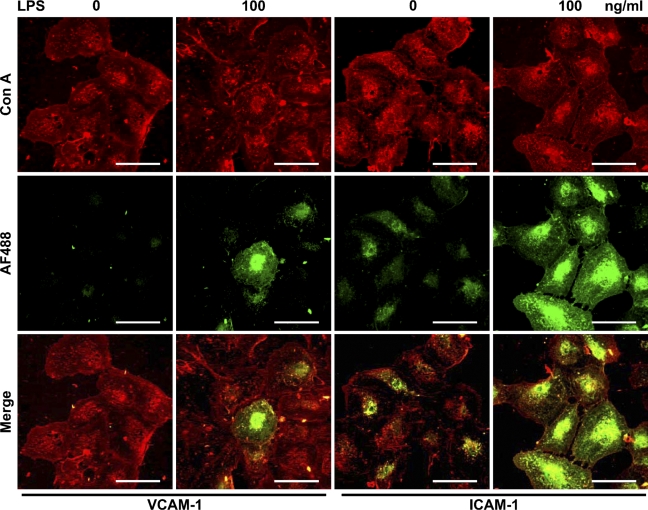

Immunohistochemical Analysis of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 Induction by LPS

VCAM-1 expression was not immunohistochemically observed in LEC but was observed in the cells with 100 ng/ml LPS. ICAM-1 expression was observed in LEC and increased with 100 ng/ml LPS (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical analysis for the effect of LPS on vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression. Cells were visualized with rhodamine-conjugated Con A (Con A, in red). Reaction products with antibodies for VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 were visualized with an AF488-conjugated second antibody (AF488, in green) in human neonatal dermal LEC. Merged images indicate that expression of VCAM-1 was not observed in LEC but was observed in the cells with LPS, and that expression of ICAM-1 was observed in LEC and strongly in the cells with LPS. Bar = 100 μm.

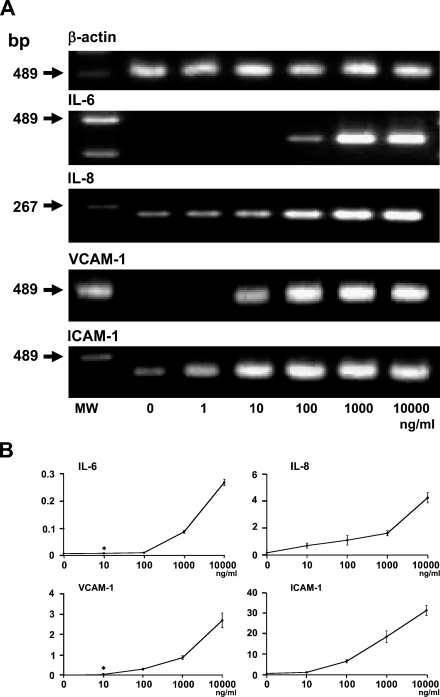

Induction of IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNAs by LPS

The RT-PCR analysis showed that IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNAs in LEC increased by LPS (Figure 4A). The IL-6 mRNA was not detected in LEC but was detected in the cells with 100 ng/ml LPS, and drastically increased in the cells with 1 μg/ml LPS. The IL-8 mRNA was detected in LEC and increased in a dose-dependent manner. The VCAM-1 mRNA was not detected in LEC but was detected in the cells with 10 ng/ml LPS, and drastically increased in the cells with 100 ng/ml LPS. The ICAM-1 mRNA was detected in LEC and increased in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 4.

Induction of interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNAs by LPS. (A) RT-PCR analysis. Expression of IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNAs in LEC increased with LPS treatment for 24 hr. RT-PCR products for IL-6 mRNA were not detected in LEC but were detected in the cells with 100 ng/ml LPS, and were drastically increased in the cells with 1 μg/ml LPS. RT-PCR products for IL-8 mRNA were detected in LEC and increased in a dose-dependent manner. RT-PCR products for VCAM-1 mRNA were not detected in LEC but were detected in the cells with 10 ng/ml LPS, and drastically increased in the cells with 100 ng/ml LPS. RT-PCR products for ICAM-1 mRNA were detected in LEC and increased in a dose-dependent manner. MW, molecular weight marker. (B) Real-time quantitative PCR analysis. LEC with 100 ng/ml and 10 μg/ml LPS showed 8.3- and 223.3-fold increases of IL-6 mRNA, 6.9- and 26.6-fold increases of IL-8 mRNA, 10.7- and 91.3-fold increases of VCAM-1 mRNA, and 84.5- and 390-fold increases of ICAM-1 mRNA, when compared with untreated cells. *Not significantly different from the untreated cells.

The real-time PCR analysis showed that the amounts of IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNAs in LEC with 10 μg/ml LPS were 26.9-, 3.9-, 8.5-, and 4.6-fold higher, respectively, than those in cells with 100 ng/ml LPS.

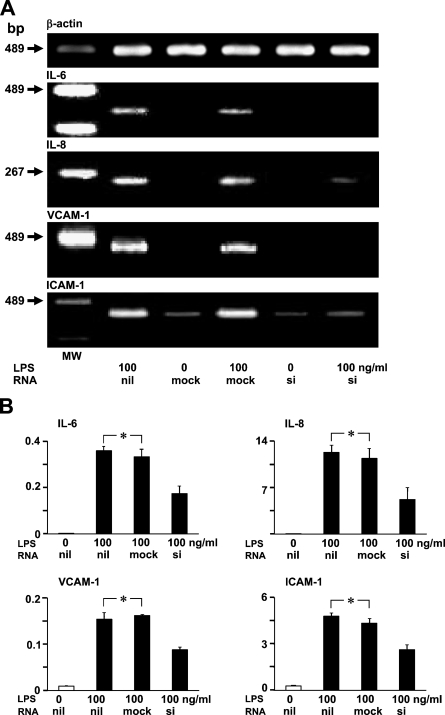

Effect of TLR4-specific siRNA on LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNA Production

The RT-PCR analysis showed that TLR4-specific siRNA leads to a silencing effect on LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNA production in LEC (Figure 5A). The real-time PCR analysis showed that LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNA expression was not statistically significantly different from the expression in mock-transfected LEC (Figure 5B). The introduction of TLR4-specific siRNA suppressed LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNA expression in LEC to ∼50% levels compared with mock-transfected LEC (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Effect of TLR4-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) introduction on LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNA production. (A) RT-PCR analysis of LEC. RT-PCR products for IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNA decreased in siRNA-transfected LEC with LPS when compared with LEC with only LPS, and with mock and LPS. MW, molecular weight marker. (B) Real-time quantitative PCR analysis. LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNA amounts in siRNA-transfected LEC were ∼50% of LEC with only LPS, and of LEC with mock and LPS. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. *Not significantly different.

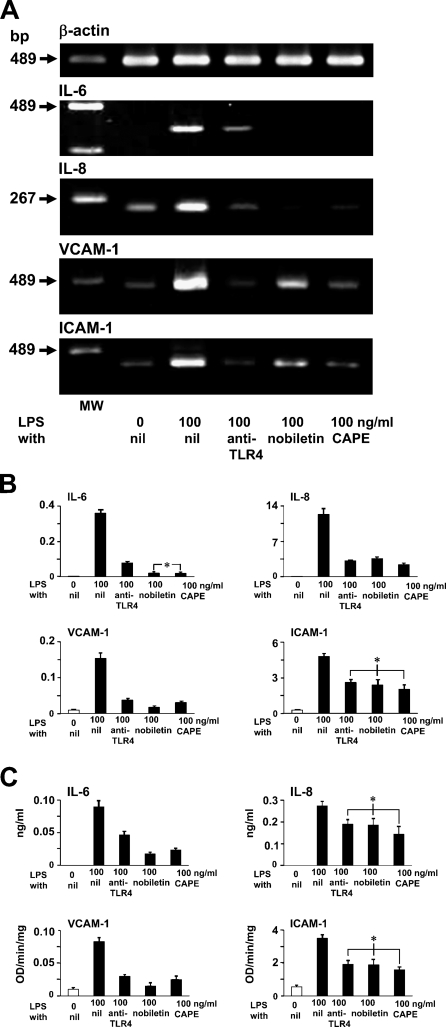

Effects of Anti-TLR4, Nobiletin, and CAPE on LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 Production

The RT-PCR analysis showed that LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNA production in LEC decreased by pretreatments with anti-TLR4, nobiletin as inhibitor for AP-1, and also with CAPE as inhibitor for NF-κB (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Effects of anti-TLR4, nobiletin, and caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) on LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 production. (A) RT-PCR analysis of LEC. RT-PCR products for LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNA decreased in LEC pretreated with anti-TLR4, nobiletin, and CAPE when compared with LEC with only LPS. MW, molecular weight marker. (B) Real-time quantitative PCR analysis. The pretreatment of LEC by anti-TLR4, nobiletin, and CAPE suppressed LPS-induced mRNA production: IL-6 to 21.5%, 5.5%, and 5.2% levels; IL-8 to 25.4%, 28.9%, and 19.1% levels; VCAM-1 to 24.4%, 11.2%, and 20% levels; and ICAM-1 to 54.4%, 49.8%, and 42.3% levels when compared with LPS-stimulated cells not pretreated. (C) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The pretreatment of LEC by anti-TLR4, nobiletin, and CAPE suppressed LPS-induced protein production: IL-6 to 52.2%, 20%, and 26.7%; IL-8 to 69.3%, 67.9%, and 52.6%; VCAM-1 to 36.1%, 18.1%, and 30.1%; and ICAM-1 to 54.7%, 53.8%, and 45.3% when compared with LPS-stimulated cells not pretreated. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM. *Not significantly different.

The real-time PCR analysis showed that anti-TLR4, nobiletin, and CAPE pretreatment of LEC suppressed LPS-induced mRNA production of IL-6 to 21.5%, 5.5%, and 5.2%; IL-8 to 25.4%, 28.9%, and 19.1%; VCAM-1 to 24.4%, 11.2%, and 20%; and ICAM-1 to 54.4%, 49.8%, and 42.3% when compared with LPS-stimulated cells not pretreated (Figure 6B).

The ELISA showed that anti-TLR4, nobiletin, and CAPE pretreatments on LEC suppressed LPS-induced protein production of IL-6 to 52.2%, 20%, and 26.7%; IL-8 to 69.3%, 67.9%, and 52.6%, VCAM-1 to 36.1%, 18.1%, and 30.1%, and ICAM-1 to 54.7%, 53.8%, and 45.3% when compared with LPS-stimulated cells that were not pretreated (Figure 6C).

Discussion

Expression of Lymphatic Endothelial Markers

Podoplanin is a novel marker for the lymphatic endothelium. The production of podoplanin is regulated by the lymphatic-specific homeobox gene Prox1, which is a lymphatic endothelial cell proliferation inducer. Podoplanin and Prox1 are critical molecules for lymphvasculogenesis, because podoplanin−/− or Prox1−/− mice have defects in lymphatic but not in blood vessel pattern formation (Wigle and Oliver 1999; Kriehuber et al. 2001; Schacht et al. 2003). The expression of Prox1 and podoplanin was immunohistochemically observed in the nuclei and in the cytoplasm and cell membrane in LEC, whereas neither Prox1 nor podoplanin was detected in HUVEC (Figure 1A). Podoplanin and Prox1 mRNAs were detected in LEC by microarray analysis, RT-PCR, and real-time PCR analysis, whereas neither Prox1 nor podoplanin mRNAs were detected in HUVEC, suggesting that LEC is reliable as a lymphatic endothelial cell phenotype (Table 1; Figures 1B and 1C). The podoplanin mRNA increased in LEC with LPS, and Prox1 gene expression showed a 2-fold increase compared with untreated cells at 30 min. Because podoplanin production is regulated by a transcription factor Prox1 (Hong et al. 2002), LPS stimulation may induce podoplanin production in lymphatic endothelium through Prox1 activation.

Expression of the Genes Participating in TLR4-mediated Cell Activation

The expression of TLR4 and MD-2 was confirmed in LEC at the gene and protein levels by immunostaining, RT-PCR, and microarray analysis, suggesting that these complexes are able to participate in the LPS recognition systems of LEC (Figure 2; Table 1). The gene expression levels did not change as well as the dynamics, which has been reported in blood endothelium (Table 1)(Ogawa et al. 2003). The CD14 was detected by immunostaining and RT-PCR but was statistically absent by microarray analysis in LEC although present in cells treated with LPS. The CD14 gene encodes two protein forms: a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane protein and a monocyte- or liver-derived soluble serum protein (sCD14) that lacks the anchor, and both molecules are able to bind LPS and translate it to the TLR4 and MD-2 complex. The sCD14 enables responses to LPS in cells not expressing CD14, because the anchor is not needed for a signal transduction (Frey et al. 1992; LeVan et al. 2001). It is thought that the production of CD14 mRNA occurs rarely in resting lymphatic endothelium, and that sCD14 contained in the serum could bind and confer LPS sensitivity to lymphatic endothelium. The LPS induces a dose-dependent increase of CD14 (Moller et al. 2005). The increase of CD14 with high concentrations of LPS could affect the LPS sensitivity in lymphatic endothelium.

The activation of the TLR4 signaling pathway originates from the cytoplasmic TIR domains. The TLR4 mediates a response in association with the TIR domain-containing adaptors MyD88, TIRAP, and TRAM, through the homophilic interaction of TIR domains. The association of TLR4 with MyD88 recruits IRAK1 and TRAF6. The IRAK1 and TRAF6 then dissociate from the complex and associate TAK1. The TAK1 activation in turn activates NF-κB and AP-1 through the IKK complex and MAPKs pathway, respectively (Uematsu and Akira 2006). The microarray analysis showed the usual gene expression of these signal transducers in LEC without any changes by LPS (Table 1). It is thought that the TLR4 ligand engagement is able to induce the activation of NF-κB and AP-1 in lymphatic endothelium.

LPS-induced Gene Expression for IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1

The LPS-induced signal transduction results in the up-regulation of IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 by at least NF-κB binding to the promoter regions of the genes. The LPS induces a marked activation of NF-κB, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), resulting in the increase of IL-6 and IL-8 secretion, and the VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 upregulation. The LPS-induced IL-8 secretion is completely inhibited by the IkappaB super repressor and partially inhibited by a specific JNK inhibitor (Paik et al. 2003; Zeuke et al. 2002). The study here showed IL-6 gene expression in LEC by microarray analysis, and showed that the expression drastically increased with high concentrations of LPS (Table 1; Figure 4). It was also shown that LEC usually expressed the IL-8 gene and that the expression increased with LPS in a dose-dependent manner (Table 1; Figure 4). These findings suggest that human lymphatic endothelium has the ability to enhance the expression of IL-6 and IL-8 in response to LPS stimulation.

We have previously reported that human intestinal lymphatic vessels expressed VCAM-1, ICAM-1, ICAM-3, and PECAM-1 (Sawa et al. 1999). The study here showed that LEC rarely expressed VCAM-1 but expressed VCAM-1 with LPS, whereas LEC expressed ICAM-1 and increased the expression with LPS (Figure 3). The VCAM-1 gene expression was detected in LEC by microarray analysis, and the expression drastically increased with high concentrations of LPS (Table 1; Figure 4). The LEC also expressed the ICAM-1 gene, and the expression increased with LPS in a dose-dependent manner (Table 1; Figure 4). These findings suggest that human lymphatic endothelium has the ability to enhance the expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in response to LPS stimulation.

The ratio of mRNA production increase for IL-6, and that for VCAM-1 in LEC with LPS at high concentrations, was significantly larger than that for IL-8 and ICAM-1 (Table 1; Figures 3 and 4). There may be a low-level LPS first response and then a high-level LPS last-resort response in the IL-6 and VCAM-1 expression pathways. It has been reported that LPS pretreatment inhibited the expression of VCAM-1 and IL-6, whereas ICAM-1 and IL-8 were not altered (Ogawa et al. 2003). The LPS-induced expression pathway for IL-6 and VCAM-1 may not coincide with that for IL-8 and ICAM-1 in activating lymphatic endothelium.

LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 Production

The production of LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNA in LEC was suppressed by the introduction of TLR4-specific siRNA, and the silencing effects were at ∼50% levels compared with mock-transfected LEC (Figure 5). The LPS-induced IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 production was suppressed by anti-TLR4 to 25–55% at mRNA levels and to 35–70% at protein levels of those of LPS-stimulated cells not pretreated (Figures 6A, 6B, and 6C). These findings suggest that human lymphatic endothelium has the TLR4-dependent LPS recognition systems that induce IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNA production. The incomplete suppression by siRNA and anti-TLR4 may suggest the existence of TLR4-independent LPS recognition systems, resulting in NF-κB activation (Girardin et al. 2003).

The nobiletin and CAPE pretreatment of LEC suppressed LPS-induced mRNA production of IL-6 to 5%, IL-8 to 20–30%, VCAM-1 to 10–20%, and ICAM-1 to 40–50% of those of LPS-stimulated cells without pretreatment (Figures 6A and 6B). The pretreatment also suppressed LPS-induced protein production of IL-6 to 20–30%, IL-8 to 50–70%, VCAM-1 to 20–30%, and ICAM-1 to 45–55% of those of LPS-stimulated cells without pretreatment (Figure 6C). CAPE is an inhibitor specific for NF-κB, and nobiletin is able to inactivate both NF-κB and AP-1 (Natarajan et al. 1996; Sato et al. 2002; Murakami and Ohigashi 2006). The IL-6 and IL-8 promoter regions have binding sites for NF-κB and AP-1, and NF-κB activation is critical for IL-6 and IL-8 production (Kunsch and Rosen 1993; Matsusaka et al. 1993; Miyazawa et al. 1998; Roebuck 1999; Georganas et al. 2000). Blood endothelium has the signaling pathway of NF-κB and AP-1 activation, resulting in increased expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 (Ahmad et al. 1998; Ishizuka et al. 1998; Lawson et al. 1999; Roebuck 1999). It is thought that IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 suppression in LEC with nobiletin and CAPE is ascribed to the NF-κB inhibition because of the small differences between nobiletin and CAPE pretreatments, and that lymphatic endothelium produced these molecules through at least the NF-κB-dependent pathway activated by LPS recognition with TLR4. The suppression effects by nobiletin and CAPE on mRNA and protein production were larger in IL-6 and in VCAM-1 than in IL-8 and in ICAM-1 (Figure 6). The signal transduction of the NF-κB-dependent pathway may be more critical for IL-6 and VCAM-1 gene expression than for IL-8 and ICAM-1 gene expression in LEC.

In conclusion, it is suggested that the human lymphatic endothelial phenotype has the TLR4-mediated LPS recognition mechanisms, which involve at least activation of NF-kB, resulting in increased expression of IL-6, IL-8, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1. The production of these molecules drastically increased in LEC with a high level of LPS at both mRNA and protein levels, and did not reach tolerance. In the lymph node and lymphatic circulation, plenty of PAMPs accumulated in the infected somatic tissue like sepsis; lymphatic endothelium may dramatically contribute to the collection of leukocytes, with the expression of immunological functional molecules playing the role of inducer from tissue into the lymphatic vessels, and may protect tissue from excessive self-defense systems.

References

- Aderem A, Ulevitch RJ (2000) Toll-like receptors in the induction of the innate immune response. Nature 406:782–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Theofanidis P, Medford RM (1998) Role of activating protein-1 in the regulation of the vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 gene expression by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J Biol Chem 273:4616–4621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreakos E, Sacre SM, Smith C, Lundberg A, Kiriakidis S, Stonehouse T, Monaco C, et al. (2004) Distinct pathways of LPS-induced NF-kappa B activation and cytokine production in human myeloid and nonmyeloid cells defined by selective utilization of MyD88 and Mal/TIRAP. Blood 103:2229–2237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauphinee SM, Karsan A (2006) Lipopolysaccharide signaling in endothelial cells. Lab Invest 86:9–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebata N, Sawa Y, Nodasaka Y, Yamaoka Y, Yoshida S, Totsuka Y (2001) Immunoelectron microscopic study of PECAM-1 expression on lymphatic endothelium of the human tongue. Tissue Cell 33:211–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faure E, Equils O, Sieling PA, Thomas L, Zhang FX, Kirschning CJ, Polentarutti N, et al. (2000) Bacterial lipopolysaccharide activates NF-kappaB through toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) in cultured human dermal endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 275:11058–11063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey EA, Miller DS, Jahr TG, Sundan A, Bazil V, Espevik T, Finlay BB, et al. (1992) Soluble CD14 participates in the response of cells to lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med 176:1665–1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georganas C, Liu H, Perlman H, Hoffmann A, Thimmapaya B, Pope RM (2000) Regulation of IL-6 and IL-8 expression in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts: the dominant role for NF-kappa B but not C/EBP beta or c-Jun. J Immunol 165:7199–7206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Carneiro LA, Antignac A, Jehanno M, Viala J, Tedin K, et al. (2003) Nod1 detects a unique muropeptide from gram-negative bacterial peptidoglycan. Science 300:1584–1587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijiya N, Miyake K, Akashi S, Matsuura K, Higuchi Y, Yamamoto S (2002) Possible involvement of toll-like receptor 4 in endothelial cell activation of larger vessels in response to lipopolysaccharide. Pathobiology 70:18–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong YK, Harvey N, Noh YH, Schacht V, Hirakawa S, Detmar M, Oliver G (2002) Prox1 is a master control gene in the program specifying lymphatic endothelial cell fate. Dev Dyn 225:351–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horng T, Barton GM, Flavell RA, Medzhitov R (2002) The adaptor molecule TIRAP provides signaling specificity for Toll-like receptors. Nature 420:329–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka T, Kawakami M, Hidaka T, Matsuki Y, Takamizawa M, Suzuki K, Kurita A, et al. (1998) Stimulation with thromboxane A2 (TXA2) receptor agonist enhances ICAM-1, VCAM-1 or ELAM-1 expression by human vascular endothelial cells. Clin Exp Immunol 112:464–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens S, Beyaert R (2002) A universal role for MyD88 in TLR/IL-1R-mediated signaling. Trends Biochem Sci 27:474–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaisho T, Akira S (2002) Toll-like receptors as adjuvant receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1589:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Takeuchi O, Fujita T, Inoue J, Muhlradt PF, Sato S, Hoshino K, et al. (2001) Lipopolysaccharide stimulates the MyD88-independent pathway and results in activation of IFN-regulatory factor 3 and the expression of a subset of lipopolysaccharide-inducible genes. J Immunol 167:5887–5894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobuchi H, Roy S, Sen CK, Nguyen HG, Packer L (1999) Quercetin inhibits inducible ICAM-1 expression in human endothelial cells through the JNK pathway. Am J Physiol 277(3 Pt I):C403–C411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriehuber E, Breiteneder GS, Groeger M, Soleiman A, Schoppmann SF, Stingl G, Kerjaschki D, et al. (2001) Isolation and characterization of dermal lymphatic and blood endothelial cells reveal stable and functionally specialized cell lineages. J Exp Med 194:797–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunsch C, Rosen CA (1993) NF-kappa B subunit-specific regulation of the interleukin-8 promoter. Mol Cell Biol 13:6137–6146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroshima S, Sawa Y, Kawamoto T, Yamaoka Y, Notani K, Yoshida S, Inoue N (2004) Expression of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 on human intestinal lymphatic vessels. Microvasc Res 67:90–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson C, Ainsworth M, Yacoub M, Rose M (1999) Ligation of ICAM-1 on endothelial cells leads to expression of VCAM-1 via a nuclear factor-kappaB-independent mechanism. J Immunol 162:2990–2996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVan TD, Bloom JW, Bailey TJ, Karp CL, Halonen M, Martinez F, Vercelli DD (2001) A common single nucleotide polymorphism in the CD14 promoter decreases the affinity of Sp protein binding and enhances transcriptional activity. J Immunol 167:5838–5844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lien E, Ingalls RR (2002) Toll-like receptors. Crit Care Med 30:S1–S11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MU, Wesche H (2002) Summary and comparison of the signaling mechanisms of the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor family. Biochim Biophys Acta 1592:265–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsusaka T, Fujikawa K, Nishio Y, Mukaida N, Matsushima K, Kishimoto T, Akira S (1993) Transcription factors NF-IL6 and NF-kappa B synergistically activate transcription of the inflammatory cytokines, interleukin 6 and interleukin 8. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:10193–10197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa K, Mori A, Yamamoto K, Okudaira H (1998) Transcriptional roles of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-beta, nuclear factor-kappaB, and C-promoter binding factor 1 in interleukin (IL)-1 beta-induced IL-6 synthesis by human rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocytes. J Biol Chem 273:7620–7627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller AS, Ovstebo R, Haug KB, Joo GB, Westvik AB, Kierulf P (2005) E. coli-LPS induced a dose-dependent increase of CD14 on monocytes in whole blood. Chemokine production and pattern recognition receptor (PRR) expression in whole blood stimulated with pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Cytokine 32:304–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami A, Ohigashi H (2006) Cancer-preventive anti-oxidants that attenuate free radical generation by inflammatory cells. Biol Chem 387:387–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan K, Singh S, Burke TR, Grunberger D Jr, Aggarwal BB (1996) Caffeic acid phenethyl ester is a potent and specific inhibitor of activation of nuclear transcription factor NF-kappa B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:9090–9095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertli B, Beck-Schimmer B, Fan X, Wuthrich RP (1998) Mechanisms of hyaluronan-induced up-regulation of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression by murine kidney tubular epithelial cells: hyaluronan triggers cell adhesion molecule expression through a mechanism involving activation of nuclear factor-kappa B and activating protein-1. J Immunol 161:3431–3437 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa H, Rafiee P, Heidemann J, Fisher PJ, Johnson NA, Otterson MF, Kalyanaraman B, et al. (2003) Mechanisms of endotoxin tolerance in human intestinal microvascular endothelial cells. J Immunol 170:5956–5964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozinsky A, Underhill DM, Fontenot JD, Hajjar AM, Smith KD, Wilson CB, Schroeder L, et al. (2000) The repertoire for pattern recognition of pathogens by the innate immune system is defined by cooperation between toll-like receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97:13766–13771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik YH, Schwabe RF, Bataller R, Russo MP, Jobin C, Brenner DA (2003) Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory signaling by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology 37:979–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roebuck KA (1999) Oxidant stress regulation of IL-8 and ICAM-1 gene expression: differential activation and binding of the transcription factors AP-1 and NF-kappaB. Int J Mol Med 4:223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saharinen P, Tammela T, Karkkainen MJ, Alitalo K (2004) Lymphatic vasculature: development, molecular regulation and role in tumor metastasis and inflammation. Trends Immunol 25:387–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Koike L, Miyata Y, Hirata M, Mimaki Y, Sashida Y, Yano M, et al. (2002) Inhibition of activator protein-1 binding activity and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway by nobiletin, a polymethoxy flavonoid, results in augmentation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 production and suppression of production of matrix metalloproteinases-1 and -9 in human fibrosarcoma HT-1080 cells. Cancer Res 62:1025–1029 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa Y, Shibata K, Braithwaite MW, Suzuki M, Yoshida S (1999) Expression of immunoglobulin superfamily members on the lymphatic endothelium of inflamed human small intestine. Microvasc Res 57:100–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa Y, Sugimoto Y, Ueki T, Ishikawa H, Sato A, Nagato T, Yoshida S (2007) Effects of TNF-alpha on leukocyte adhesion molecule expressions in cultured human lymphatic endothelium. J Histochem Cytochem 55:721–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacht V, Ramirez MI, Hong YK, Hirakawa S, Feng D, Harvey N, Williams M, et al. (2003) T1alpha/podoplanin deficiency disrupts normal lymphatic vasculature formation and causes lymphedema. EMBO J 22:3546–3556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnare M, Barton GM, Holt AC, Takeda K, Akira S, Medzhitov R (2001) Toll-like receptors control activation of adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol 2:947–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uematsu S, Akira S (2006) Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. J Mol Med 84:712–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voraberger G, Schafer R, Stratowa C (1991) Cloning of the human gene for intercellular adhesion molecule 1 and analysis of its 5′-regulatory region. Induction by cytokines and phorbol ester. J Immunol 147:2777–2786 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigle JT, Oliver G (1999) Prox1 function is required for the development of the murine lymphatic system. Cell 98:769–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuke S, Ulmer AJ, Kusumoto S, Katus HA, Heine H (2002) TLR4-mediated inflammatory activation of human coronary artery endothelial cells by LPS. Cardiovasc Res 56:126–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]