Abstract

Strand-specific transcripts of a satellite DNA of the newts, Notophthalmus and Triturus, are present in cells in monomeric and multimeric sizes. These transcripts undergo self-catalyzed, site-specific cleavage in vitro: the reaction requires Mg2+ and is mediated by a “hammerhead” domain. Transcription of the newt ribozyme appears to be performed by RNA polymerase II under the control of a proximal sequence element and a distal sequence element. In vitro, the newt ribozyme can cleave in trans an RNA substrate, suggesting that in vivo it might be involved in RNA processing events, perhaps as a riboprotein complex. Here we show that the newt ribozyme is in fact present as a riboprotein particle of about 12 S in the oocytes of Triturus. In addition, reconstitution experiments and gel-shift analyses show that a complex is assembled in vitro on the monomeric ribozyme molecules. UV cross-linking studies identify a few polypeptide species, ranging from 31 to 65 kDa, associated to the newt ribozyme with different affinities. Finally, we find that an appropriate oligoribonucleotide substrate is specifically cleaved by the riboproteic activity in S-100 ovary extracts.

Keywords: hammerhead ribozymes, trans-cleavage, RNA-binding proteins

Unlike most satellite DNAs, which are confined to heterochromatin and are transcriptionally inert, a highly repetitive DNA family of newts is organized in small clusters dispersed throughout the genome and transcribed into stable, strand-specific cellular transcripts (ref. 1; unpublished data). Most satellite 2 transcripts correspond in size to the entire repeat unit (about 330 nt) or to whole multiples of the repeat. While the monomer-sized transcripts are predominant in the ovary, the multimeric forms are relatively more abundant in somatic tissues.

Remarkably, synthetic dimeric transcripts of the satellite 2 DNA undergo self-catalyzed, site-specific cleavage in vitro at one site (GUC) in each repeat unit (2, 3). The reaction requires Mg2+ and generates products with 5′-hydroxyl and 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate ends. The cleavage site is in a region that has many of the conserved sequence and structural elements of the “hammerhead” ribozyme domain required for the cleavage of some infectious RNA genomes of plants (4, 5). An intriguing difference between the monomeric transcripts in somatic tissues and testes, on one side, and those in the ovary, on the other, has been reported (6). Somatic and testes transcripts have ends that map to the in vitro self-cleavage site, as well as end groups (5′-hydroxyl and 3′-cyclic phosphate) similar to those produced by self-cleavage; these findings led to the suggestion that these monomers may originate by in vivo self-cleavage of multimers at the specific GUC site (6). On the other hand, in the monomeric transcripts of the ovary, the 5′ ends are situated about 50 nt upstream from the in vitro self-cleavage site, thus suggesting that the ovarian monomers could originate by a mechanism different from cleavage at the GUC site (2). By addressing this question (3), we found that the ovarian monomers could originate by transcription and not by cleavage. In addition, regulation of transcription of the ovarian monomers appears to be similar to that of small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), such as the U RNAs (7), in that it is carried out by RNA polymerase II and is controlled by a proximal sequence element and a distal sequence element (3). These findings have been recently confirmed (8). In addition, the work of Coats et al. (8) gives strength to the similarity between the newt ribozyme and the snRNA promoters, by showing that the satellite 2 promoter initiates transcription of Xenopus U1b2 snRNA gene as efficiently as the native promoter.

The U RNAs are known to play crucial roles in the cell metabolism as ribonucleoprotein (RNP) particles (7). Given the analogous mode of transcription between the U RNAs and the newt ribozyme, we wondered whether the newt ribozyme could also be assembled as a small RNA–protein complex in the cell. We reasoned that its catalytic ability could be exploited for a possible cellular function of such a putative particle, such as trans-cleavage of different RNA molecules (3, 9).

In this report, we describe the identification and the initial characterization of a small riboprotein complex, containing the newt monomeric ribozyme, present in the Triturus oocytes, by using sucrose gradient sedimentation and native gel-shift analysis. In addition, by in vitro trans-cleavage assays with S-100 cytoplasmic extracts, we gained evidence supporting the possible site-specific cleavage of a target RNA by the ribozyme–protein complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clones and Preparation of Transcripts.

The 330 nt ribozyme (called newt-Rz), which is similar to the monomeric ribozyme found in the ovary, is a T7 RNA polymerase transcript of the pGEM-AluI clone (3). The pDIM clone contains an incomplete dimer, 597 nt long, of the “BglII” sequences of Triturus vulgaris meridionalis cloned in the PstI site of the pGEM-3Z vector; transcription with SP6 RNA polymerase generates an ≈600 nt transcript, called DIM-Rz. Antisense DIM probe is obtained by transcription from the HindIII linearized pDIM clone, using T7 RNA polymerase. The pGEM-3Z vector (Promega) was digested with PvuII to serve as template for the synthesis of a control RNA (pGEM-RNA, 290 nt long). In vitro transcription of T7 or SP6 templates was performed essentially as described; to generate labeled RNAs, 25 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (Amersham; 3,000 Ci/mmol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq) were used (10). The target 12-mer oligoribonucleotide (5′-ACCGGUCCUAGG-3′; cleavage site in boldface letters) substrate was synthesized by the phosphoramidite method and purified as described (11). It was 5′ 32P-labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham; 3,000 Ci/mmol).

The in vitro transcripts were gel purified; 32P-labeled transcripts were detected in the gels by autoradiography, and the unlabeled competitor RNAs were visualized by UV shadowing and subsequently quantified by A260 absorption.

Preparation of the Tissue Extracts.

Ovaries were taken from anesthesized specimens of Triturus cristatus carnifex and Xenopus laevis. To prepare total ovary extracts, fragments of ovaries were homogenized in 600 μl of TKM solution (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.6/50 mM KCl/5 mM MgCl2) and centrifuged for 5 min in a Eppendorf centrifuge (12). S-100 cytoplasmic extracts were prepared according to Dignam et al. (13). The extracts were stored at −80°C following protein determination by the Bio-Rad assay.

Sucrose Gradient Centrifugation.

Four hundred microliters of either total or S-100 ovary extract were loaded on a 10–30% TKM–sucrose gradient (V = 12 ml), centrifuged at 35,000 rpm for 21 hr in a Beckman SW41 rotor, and fractionated into 18 samples. Samples were phenol-chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated, and after resuspension, the RNA of each sample was analyzed by Northern blot, by using 32P-labeled antisense DIM-Rz as a riboprobe. As a control experiment, the ovary extract was deproteinized by phenol extraction and applied to a sucrose gradient run in parallel. Analyses by glycerol gradient centrifugation were performed as described (14).

Gel Retardation Assay and UV Cross-Linking.

RNA–protein binding reactions were carried out with the S-100 cytoplasmic extract (50 μg of total proteins) and 50,000 cpm (1 ng) of 32P-labeled newt-Rz or DIM-Rz RNA in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.9), 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 10% glycerol in a volume of 20 μl. To reduce nonspecific RNA–protein interactions, tRNA was added to the mixture at a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml. Incubation was carried out at 30°C for 30 min. Competition experiments were performed by preincubating the extract with the indicated molar excess (see Fig. 2A) of a specific or unspecific RNA competitor for 15 min at 30°C before the addition of the labeled RNA. Electrophoresis of RNA–protein complexes was carried out as described (15). Autoradiographic exposure of the gel was at −80°C with intensifying screen. For the UV cross-linking experiments, radioactive newt-Rz RNA and pGEM-RNA were incubated in S-100 cytoplasmic extract that had been preincubated with no RNA or with unlabeled specific, or nonspecific, competitor RNA (see Fig. 3). The binding reaction products were placed on ice and exposed to UV light for 40 min using a 254 nm 25 W germicidal lamp placed 3 cm above the samples. Following exposure, the samples were treated for 30 min with RNase A (1 mg/ml) and RNase T1 (2.5 units/ml). Samples were then boiled for 5 min in 5× Laemmli buffer and run on 12–15% SDS/polyacrylamide gel (16). The gels were dried and subject to autoradiography to visualize the proteins, tagged because of the label transfer.

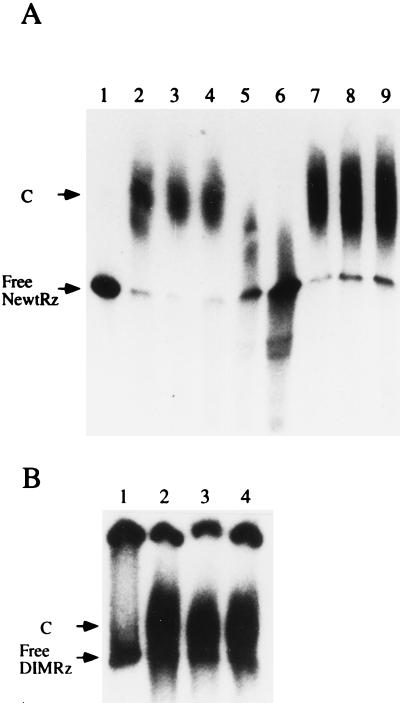

Figure 2.

Gel retardation analysis. (A) 32P-labeled monomeric newt-Rz was incubated with S-100 ovary extract and analyzed by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis. Lanes: 1, protein-free newt-Rz RNA; 2 and 3, extracts lacking competitor RNA; 4–9, extracts containing 10-, 100-, or 500-fold molar excess of a nonradioactive competitor RNA, either specific (newt-Rz RNA, lanes 4–6) or nonspecific (pGEM-RNA, lanes 7–9), respectively. In lanes 3–9, tRNA was added to the reaction at the concentration of 0.1 mg/ml. (B) The 32P-labeled dimeric ribozyme, DIM-Rz, was mixed with S-100 ovary extract and analyzed by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis. Lanes: 1, protein-free DIM-Rz RNA; 2, extract lacking competitor RNA; 3 and 4, extract containing a 500-fold molar excess of unlabeled DIM-Rz RNA, as a specific competitor (lane 3) or pGEM-RNA as a nonspecific competitor (lane 4). Arrow indicates the position of free DIM-Rz RNA. C indicates the RNA–protein complex.

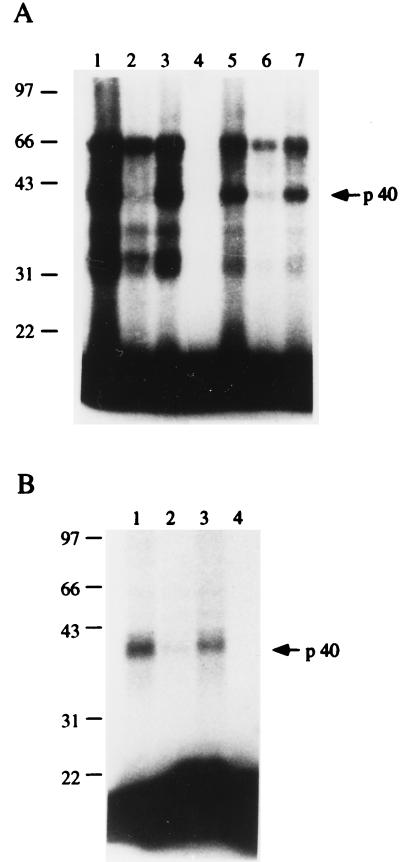

Figure 3.

Identification of ribozyme binding proteins by UV cross-linking. (A) 32P-labeled newt-Rz RNA (lanes 1–4) or pGEM-RNA (lanes 5–7) were incubated with S-100 ovary extract from Triturus in the absence (lanes 1, 4, and 5) or in the presence of a molar excess of unlabeled newt-Rz RNA (lanes 2 and 6) or pGEM-RNA (lanes 3 and 7). The samples were irradiated with UV light, treated with RNase A and RNase T1, and subjected to electrophoresis on SDS/12% PAGE. Lane 4, irradiated samples treated with RNases plus proteinase K. (B) 32P-labeled newt-Rz RNA incubated with S-100 ovary extract from X. laevis in the absence (lane 1) or in the presence of a molar excess of unlabeled newt Rz-RNA (lane 2) or pGEM-RNA (lane 3). The samples were treated as above. Lane 4, irradiated samples treated with RNases plus proteinase K. Molecular weight protein standards are indicated on the left. Arrow indicates the p40 protein.

Cleavage Reaction with S-100 Cytoplasmic Extract.

The cleavage assay was carried out in a 25 μl reaction mixture containing 50 nM 5′ 32P-12-mer labeled substrate/15 μl S-100 cytoplasmic extract corresponding to a protein content of 30 μg, 5× processing buffer (50 mM Hepes⋅KOH, pH 7.5/50 mM MgCl2/3 mM DTT/0.75 M KCl/0.5 mM EDTA/30% glycerol), 1 mg/ml yeast tRNA, 80 units of RNase inhibitor (RNase-In, Promega), 0.5 mM ATP, 10 mM phosphocreatine, at room temperature for 20 min. To disrupt aggregation states potentially formed during RNA storage (17), solutions of radiolabeled substrate RNA were heated in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5) at 95°C for 1 min and allowed to cool to room temperature. The reaction was terminated by adding 20 μl of 3 M sodium acetate, 20 μl of 0.1 M EDTA, 2 μl of 20 mg/ml glycogen and H2O to a final volume of 200 μl. The mixture was phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1 vol/vol) extracted and precipitated with ethanol. The cleavage products were compared with the products of a limited alkaline digestion and to the in vitro cleavage reaction of the same 12-mer RNA. The reaction products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 20% acrylamide/8 M urea gels.

Micrococcal Nuclease and Proteinase K Treatment.

Micrococcal nuclease digestion (5,000 units/ml of extract) of the S-100 extracts was carried out as described (18). For proteinase K treatment, 40 μl of S-100 extract were incubated at 37°C for 30 min with 40 μg of proteinase K (20 mg/ml). Assays for cleavage activity were performed with 15 μl of treated extracts using the standard assay conditions (see above). To assay for the occurrence of the ribozyme in the micrococcal nuclease- or the proteinase-treated extracts, samples were phenol-chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated, and analyzed by Northern blot hybridization.

RESULTS

The Newt Ribozyme Migrates as an RNA–Protein Complex on Sucrose Gradient.

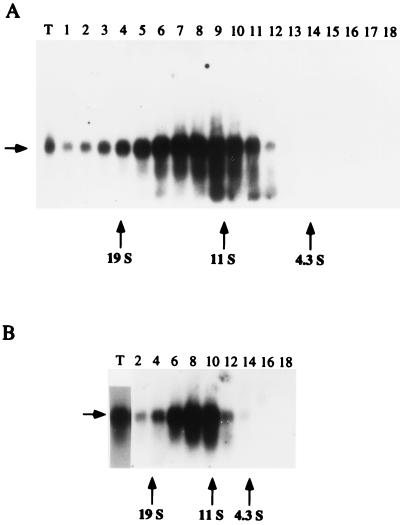

When total ovary extracts from Triturus are fractionated on a sucrose gradient and the RNA isolated from each gradient fraction is analyzed by Northern blot hybridization, a peak of the ribozyme is found around a sedimentation value of 12 S (Fig. 1A, fractions 11 to 6), a value characteristic of the U RNPs in eukaryotes (7). Deproteinization of the extract shifts the sedimentation coefficient of the ribozyme to about 7 S (data not shown). It thus appears that the newt ribozyme is present in the total ovary extract as a small RNA–protein complex. Like some cellular U RNPs (7), the ribozyme–protein complex is also dispersed throughout the gradient toward higher sedimentation coefficients (Fig. 1A, fractions 11 to 1). These data suggest that the 12 S material may associate with other cellular components to give rise to higher order complexes. The sedimentation profile in glycerol gradients (not shown) agrees with that in sucrose gradients. Fractionation on sucrose gradient of S-100 cytoplasmic extract from ovary results in a ribozyme distribution very similar to that obtained with total ovary extract (Fig. 1B). Finally, it is noteworthy that within the range of sedimentation values provided by the present gradients, the monomeric transcripts only are revealed as part of a riboproteic complex in both total and S-100 ovary extracts (Fig. 1).

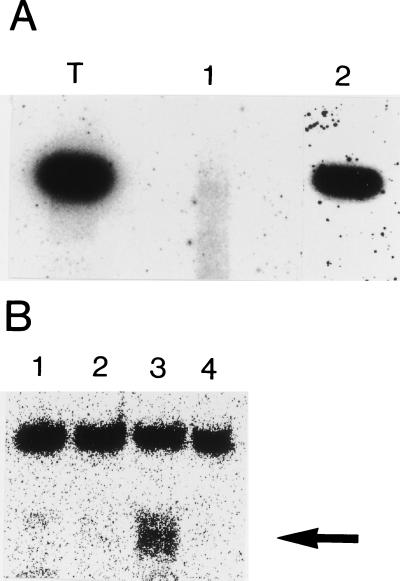

Figure 1.

Velocity sedimentation-gradient analysis of total ovary extract (A) and S-100 cytoplasmic extract (B) from Triturus. Only even fractions from S-100 cytoplasmic extract were subject to Northern blot analysis. Lane T, total RNA from total (A) or from S-100 (B) ovary extract. S values were determined relative to BSA (4.3 S), catalase (11.3 S), and thyroglobulin (19 S) applied to a parallel gradient. Fraction numbers are from bottom to top. Arrow on the left indicates the 330 nt newt-Rz RNA.

Demonstration of an in Vitro RNA–Protein Complex.

To confirm the existence of a ribozyme–protein complex we used an in vitro reconstitution approach. This approach makes use of a pool of unassembled proteins present in the S-100 cytoplasmic extract (19, 20) and of the 330 nt newt-Rz transcript as a 32P-labeled probe. In this assay, the majority of the input RNA forms a distinct complex whose electrophoretic migration is retarded in the gel (Fig. 2A: compare lanes 2 and 3 with lane 1). Optimal binding is achieved after a 30 min incubation at 30°C; ATP is not required for binding. To determine the specificity of the complex, we performed reconstitution reactions under competitive conditions by preincubating the reaction mixture with unlabeled competitor RNA. Addition of a 100-fold molar excess of unlabeled newt-Rz RNA greatly reduces the amount of the complex formed (Fig. 2A, lane 5); a higher concentration of competitor (500-fold) completely abolishes the slowly migrating complex, and the 32P-labeled RNA is found to migrate nearly as rapidly as the naked RNA (Fig. 2A, lane 6). The occurrence of the slowly migrating complex is not prevented by competition with a similarly sized RNA transcript of pGEM vector sequences (Fig. 2A, lanes 7–9), or with other unrelated RNA sequences (data not shown). When the same experiment is performed using 32P-labeled DIM-Rz RNA (a dimeric ribozyme) in the S-100 extract, a complex is formed (Fig. 2B, lane 2). However, reconstitution under competitive conditions shows the nonspecific nature of this complex: addition of a 500-fold molar excess of either unlabeled DIM-Rz or unlabeled pGEM transcripts, as specific or nonspecific competitors, respectively, is uneffective in abolishing the complex formation (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4).

Identification of Proteins Binding the Newt Ribozyme.

To identify the protein component(s) of the S-100 cytoplasmic ovary extract of Triturus that binds the newt-Rz RNA, we used UV cross-linking label transfer analysis; 32P-labeled pGEM-RNA was used as a control RNA (Fig. 3A). Proteins in five size classes of about 65 kDa (p65), 40 kDa (p40), 35 kDa (p35), 32 kDa (p32), and 31 kDa (p31) are identified as interacting with 32P-labeled newt-Rz transcript (lane 1); their proteic nature is confirmed by treatment with proteinase K (lane 4). The level of labeling is lower when pGEM-RNA rather than newt-Rz RNA is used as the label source; in addition, labeling is very evident at the p65 and p40 protein species, whereas it is comparatively weaker at the other protein fractions (confront lanes 1 and 5; and data not shown). The pattern of labeling produced by the pGEM sequences is only slightly affected by competition with the same, nonradioactive RNA (lane 7). It is nearly abolished by nonradioactive newt-Rz RNA, with labeling of p65 the least affected (lane 6); there is nearly complete disappearance of labeling of the p40 protein fraction. In contrast, when radioactive newt-Rz RNA is bound, the nonspecific competitor pGEM-RNA does not substantially modify the labeling pattern of the protein fractions (compare lanes 1 and 3). At variance, competitor, nonradioactive newt-Rz RNA results in an overall reduction of labeling, with labeling of p65 being the least affected; labeling of p40 is nearly abolished (lane 2). These results suggest that the identified protein fractions ranging from p31 to p65 can bind the newt ribozyme as well as the nonspecific pGEM RNA, although competition experiments indicate that some protein fractions (e.g., p40) can bind the newt ribozyme with a higher affinity. We then asked whether these protein fractions are confined to Triturus, the host organism for the ribozyme, or represent more widespread RNA-binding proteins. UV cross-linking experiments with S-100 ovary extracts from X. laevis (Fig. 3B) reveal that a 40-kDa protein in the X. laevis extract binds the newt-Rz (lane 1). While competition with unlabeled newt-Rz abolishes binding (lane 2), nonspecific competition with the pGEM transcript affects the labeling only partially (lane 3), thus supporting the possible higher affinity of the p40 protein for the newt-Rz, than for other RNA species. The proteic nature of the Xenopus 40-kDa species is shown by treatment with proteinase K, which prevents detection of radioactivity at the p40 level (lane 4).

Trans-Cleavage Reaction in the S-100 Cytoplasmic Extract.

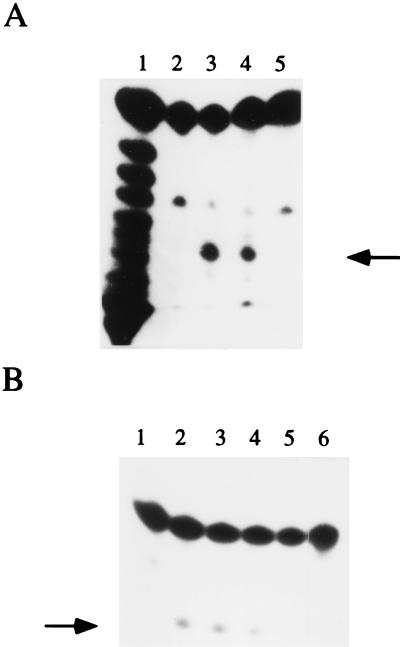

Because a monomeric ribozyme corresponding to the ovary transcripts is able to trans-cleave in vitro a small RNA substrate (3), we wondered whether the ribozyme–protein complex present in the ovarian extracts could possess a similar trans-cleavage activity. To address this question, a ribozyme substrate was incubated in the Triturus S-100 cytoplasmic extract in physiological conditions. The substrate is a 5′ 32P-labeled 12-mer RNA containing a GUC target site and capable of constituting a hammerhead structure upon association with the ribozyme. In the presence of the extract, an oligonucleotide of 7 nt is observed (Fig. 4A, lane 4); this fragment can derive by specific cleavage at the 3′ side of the GUC target site (3), since it is also shown by the similar result of a parallel in vitro cleavage experiment in nonphysiological conditions (Fig. 4A, lane 3). No cleavage is observed in the absence of the ribozyme under these conditions (lane 2). The 7 nt fragment is not produced in absence of the extract (lane 5). To verify whether the observed specific endoribonuclease activity was due to the ribozyme–protein complex found in the ovary extract, we tested whether this activity would require both an RNA and a protein component; this was done by pre-digesting the S-100 extract with micrococcal nuclease or proteinase K (Fig. 4B). Micrococcal nuclease requires Ca2+ and degrades both RNA and DNA. Preincubation of S-100 extract in the presence of Ca2+ alone (lane 3) or micrococcal nuclease alone (lane 4) had no significant effect on the cleavage activity of the extract (lane 2). However, pre-incubation in the presence of both micrococcal nuclease and Ca2+ prevented cleavage (lane 5). Because DNase I pretreatment does not eliminate the cleavage capacity of the extract (data not shown), the nucleic acid required for activity should be RNA, rather than DNA. On the other hand, digestion of the S-100 extract with proteinase K abolishes the cleavage activity (lane 6). Northern blot analysis on total RNA of proteinase K- or micrococcal nuclease-treated S-100 extracts (Fig. 5A), shows that the proteinase K digestion does not remove the ribozyme (lane 2), whereas micrococcal nuclease digestion completely removes it (lane 1). Because the labeled product of the trans-cleavage experiments is of the expected size (7 nt), these results suggest that the cleavage activity can be assigned to the Rz–riboproteic complex.

Figure 4.

Processing activity of the S-100 extract. (A) Lanes: 1, limited alkaline digestion of the 5′ 32P-labeled 12-mer substrate; 2, 12-mer substrate under the same conditions as in lane 3 but for the absence of the newt-Rz; 3, in vitro cleavage with the newt-Rz of the 12-mer substrate in nonphysiological conditions (see text); 4, incubation of the 12-mer substrate in Triturus S-100 ovary cytoplasmic extract in physiological conditions; 5, reaction as in lane 4, but in the absence of the S-100 extract. (B) The 12-mer substrate incubated with the Triturus S-100 ovary extract (lane 2) or in presence of control treatments (lanes 3–6). Lanes: 1, substrate in the absence of the S-100 ovary extract; 3–6, substrate-incubated extracts treated with CaCl2 (lane 3), micrococcal nuclease (lane 4), both CaCl2 and micrococcal nuclease (lane 5), and proteinase K (lane 6). Arrows indicate the 7 nt fragment.

Figure 5.

(A) Northern blot analysis of the ribozyme in proteinase K- or micrococcal nuclease-treated S-100 extracts. Lanes: T, total RNA from S-100 ovary extract; 1, total RNA from micrococcal nuclease-treated extract; 2, total RNA from proteinase K-treated extract. (B) In vitro reconstitution of endoribonuclease activity. Lanes: 1, 5′ 32P-labeled 12-mer substrate; 2–4, cleavage assay (see Materials and Methods) of 10 nM 5′ 32P-labeled 12-mer substrate incubated with 25 μg of total RNA of proteinase K-treated S-100 extract (lane 2), micrococcal nuclease-treated S-100 extract (lane 3), 100 ng/μl of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Boehringer Mannheim) (lane 4). Arrow indicates the 7 nt fragment.

This conclusion is reinforced by in vitro reconstitution experiments (Fig. 5B). Whereas the RNA from the protein-depleted S-100 extract was unable to perform cleavage (lane 2), the cleavage activity was reconstituted by the addition of the micrococcal nuclease-treated S-100 extract to the protein-depleted S-100 extract (lane 3). This result indicates that both cellular proteins and RNA are essential for activity. The cytoplasmic RNA chaperone protein glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (21) was unable to reconstitute the cleavage activity (lane 4).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that the newt ribozyme found in the ovary is assembled into a small riboprotein complex, which can also be obtained in vitro by reconstitution experiments. In addition, a site-specific endoribonuclease activity, present in the ovary extract, is probably ascribable to the ribozyme–protein complex.

Sedimentation experiments on sucrose (Fig. 1A) or glycerol (data not shown) gradients reveal that the monomeric (330 nt) ribozyme (newt-Rz) is dispersed throughout the gradients, with a major peak at about 12 S, when it is analyzed in total ovary extracts, whereas the sedimentation value of the deproteinized ribozyme is about 7 S (not shown). These results suggest that the newt-Rz is assembled into a particle of about 12 S, which can interact with another macromolecular component(s) of oocytes, to originate larger complexes. The ribozyme particle should be present in the soluble fraction of the cytoplasm, as shown by its detection in the S-100 extract (Fig. 1B), although its possible location in other oocyte compartments cannot be excluded.

In agreement with the results of the sedimentation analyses, the newt-Rz is assembled into an RNA–protein complex by in vitro reconstitution experiments (Fig. 2A), whereas the dimeric form (DIM-Rz) is not (Fig. 2B). Apparently, only the monomeric-sized transcripts contain all the information necessary to bind cellular proteins and to assemble into a small riboprotein complex. We may recall here that, at variance with testes and somatic tissues, monomers represent the preponderant fraction of the ribozyme transcripts in the ovary, where they are produced by a precisely regulated transcription (3, 8). These data point toward a possible significance for the monomeric ribozyme in the ovary.

The fundamental question concerning the newt ribozyme is its possible cellular role (3). We do not know whether the oocyte ribozyme–protein complex trans-cleaves a specific RNA target in vivo, but we show here that a site-specific endoribonuclease, capable of cleaving a short RNA substrate, is present in the S-100 oocyte extract (Figs. 4 and 5). This activity requires both an RNA and a protein component. The target RNA sequence is designed in such a way as to allow its annealing to the ribozyme, to constitute a hammerhead catalytic domain; moreover, the cleavage product is of the expected size for cleavage at the canonic GUC site. These data support the view that the observed cleavage may be ascribed to the ribozyme–protein complex. They are consistent with the possibility that, in vivo as well, the RNA component of the complex could base pair with a specific RNA target, thus assembling into a higher order complex to process a substrate RNA. The association should be relatively weak to permit the release step and to enable the complex to catalytically cleave multiple substrates.

Our assay of the ribozyme–endoribonuclease activity does not allow us to determine whether the ribozyme–protein complex can work catalytically. A recent study on the kinetics of in vitro cleavage (28) shows that the 330-nt monomeric ribozyme is not able to catalytically trans-cleave a 12-mer RNA substrate; no cleavage is observed at 25°C in 10 mM MgCl2 under single or multiple turnover conditions, whereas, in agreement with previous results (3), cleavage is observed at 45°C in 50 mM MgCl2, using an excess of ribozyme over substrate (Fig. 4A, lane 3). The poor cleavage activity of the ribozyme seems to be due to its inability to assemble into a hammerhead–substrate complex. Experiments of S1 and V1 nuclease digestion of the newt hammerhead domain support this interpretation, showing that a stable stem II is present, whereas nucleotides from stems I and III anneal in a double-stranded region, resulting in a nonhammerhead structure (D. Scarabino, personal communication). Because the present cleavage reactions in S-100 cytoplasmic extracts are carried out at room temperature in physiological conditions (Fig. 4A, lane 4), the activity of the ribozyme–protein complex is improved with respect to the in vitro activity of the synthetic ribozyme. Such an improvement could be due to the interaction of RNA with specific, or nonspecific, RNA chaperone proteins present in the cellular environment. In vitro reconstitution assays, made by using the protein-depleted and RNA-depleted S-100 extracts, show that both RNA and protein are required for cleavage activity (Fig. 5B, lane 3). The only RNA chaperone protein tested—glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase—has no effect on the reconstitution of activity (Fig. 5B, lane 4). Thus, the nature and the possible specificity of the S-100 proteins that may help the endoribonuclease activity by chaperoning the newt ribozyme into a functional conformation, remain presently undetermined.

In recent years, evidence on the profound effects of proteins on ribozyme activity have been accumulating (reviewed in ref. 22). The protein component (C5) of RNase P has been proposed to enhance product release, which is the rate-limiting step of the RNase P-catalyzed reaction in vitro (23, 24). The CYT-18 protein—the mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase—binds to Group I introns to promote RNA splicing (25, 26), and it can even replace a functional, noncatalytic RNA domain in the Tetrahymena Group I intron, thus activating splicing, possibly by stabilizing an active conformation (27). Other proteins, not designed for specific interactions with a ribozyme, can also enhance ribozyme activity. This is the case for some nucleic acid binding proteins—such as HIV-NCp7 protein, hnRNP A1 protein, Escherichia coli S12 ribosomal protein, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase—that stimulate hammerhead or Group I intron activity in vitro (see ref. 22 and references therein). Proteins present in S-100 cytoplasmic extract could similarly be required as cofactors, facilitating the newt ribozyme activity in both in vivo and in vitro extracts. As to their mechanism of action, we may speculate that, since the newt catalytic domain appears to be unable to assemble into a functional hammerhead in vitro (see above), these proteins could play a role by transforming it in an active form upon association (see ref. 22 for discussion and references). A search for such a protein(s) by UV cross-linking has identified a set of proteins that appear to bind the newt-Rz as well as the control pGEM-RNA, although with different affinities (Fig. 4A). Thus, these experiments have apparently identified a set of generic RNA-binding proteins that associate with the ribozyme in vitro. In principle, it remains possible, but it is not proven, that the interaction with the newt-Rz results in a functional complex, whereas interaction with other RNAs is unspecific. The conservation of the ribozyme-binding p40 protein in the soluble fraction of the oocyte cytoplasm in both Triturus and Xenopus may represent a preliminary indication of a more general occurrence of such a protein, recognizing a particular RNA structure and perhaps acting as an RNA chaperone.

The evolutionary relationship between satellite 2 and snRNA genes (3, 8) is reinforced by this study. Like snRNA, the newt ribozyme is assembled in vivo as a riboprotein complex, that, as suggested by the cleavage experiments in the oocyte extract, could retain the function of processing some other cellular RNAs. A few protein species are putative candidates for the enhancement of activity observed in the extract, with respect to the in vitro kinetics. This system provides a new model to study the interactions between ribozymes and proteins, and how proteins may influence ribozyme activity in the cells. Information from such a study may be useful for the application of ribozymes as therapeutic agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Andreazzoli, S. Casarosa, M. A. Denti, and L. Marusic for helpful discussions and D. Scarabino for having shared with us her unpublished work. We also thank M. Fabbri for excellent technical assistance. This work has been supported by Ministero dell’Universitá e della Ricerca Scientifica e Technologica, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (Progetto Finalizzato Ingegneria Genetica, Progetto Strategico Oligonucleoidi Antisenso) and the Human and Capital Mobility European Economic Community Program (Contract 930162).

ABBREVIATIONS

- snRNA

small nuclear RNA

- RNP

ribonucleoprotein

References

- 1.Epstein L M, Mahon K A, Gall J G. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1137–1144. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.4.1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein L M, Gall J G. Cell. 1987;48:535–543. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cremisi F, Scarabino D, Carluccio M A, Salvadori P, Barsacchi G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:161–165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Symons R H. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:641–671. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forster A C, Davies C, Sheldon C C, Jeffries A C, Symons R H. Nature (London) 1988;334:265–267. doi: 10.1038/334265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein L M, Coats S R. Gene. 1991;107:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahlberg J E, Lund E. In: Structure and Function of Major and Minor Small Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein Particles. Birnstiel M L, editor. Heidelberg: Springer; 1988. pp. 38–70. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coats S R, Zhang Y, Epstein L M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4697–4704. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kole K, Baer M F, Stark B C, Altman S. Cell. 1980;19:881–887. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melton D, Krieg P A, Rebagliati M R, Maniatis T, Zinn K, Green M R. Nucleic Acid Res. 1984;12:7035–7050. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.18.7035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tuschl T, Eckstein F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6991–6994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamm J, Mattaj I W. EMBO J. 1989;8:4179–4187. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dignam J D, Martin P L, Shastry B S, Roeder R G. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:582–598. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wassarman D A, Steitz J A. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:3432–3445. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.7.3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Konarska M M, Sharp P A. Cell. 1986;46:845–855. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laemmli U K. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groebe D R, Uhlenbeck O C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:11725–11735. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.24.11725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chabot B, Black D L, LeMaster D M, Steitz J A. Science. 1985;230:1344–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.2933810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patton J R, Patterson R J, Pederson T. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:4030–4037. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.11.4030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruskin B, Zamore P D, Green M R. Cell. 1988;52:207–219. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90509-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sioud M, Jespersen L. J Mol Biol. 1996;257:775–789. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herschlag D. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:20871–20874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reich C, Olsen G J, Pace B, Pace N R. Science. 1988;239:178–181. doi: 10.1126/science.3122322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tallsjo A, Kirsebom L A. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:51–57. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohr G, Zhang A, Gianelos J A, Belfort M, Lambowitz A M. Cell. 1992;69:483–494. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90449-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo Q, Lambowitz A M. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1357–1372. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohr G, Caprara M G, Guo Q, Lambowitz A M. Nature (London) 1994;370:147–150. doi: 10.1038/370147a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marusic L, Luzi E, Barsacehi G, Eckstein F. Eur J Biochem. 1997;247:396–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]